Think Tank (Blur album)

| Untitled | |

|---|---|

Think Tank is the seventh studio album by the English rock band Blur, released in May 2003. Jettisoning the Britpop sound of Blur's early career as well as the lo-fi indie rock of Blur (1997), Think Tank continued the jam-based studio constructions of the group's previous album, 13 (1999). The album expanded on the use of sampled rhythm loops and brooding, heavy electronic sounds. There are also heavy influences from dance music, hip hop, dub, jazz, and African music, an indication of lead singer-songwriter, Damon Albarn's expanding musical interests.

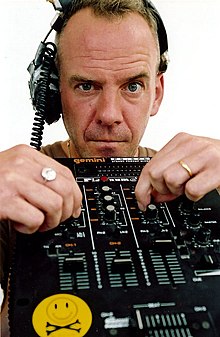

Recording sessions started in November 2001, taking place in London, Morocco and Devon, and finished a year later. The album's primary producer was Ben Hillier with additional production by Norman Cook (Fatboy Slim), and William Orbit. At the start of the sessions, guitarist Graham Coxon had been in rehab for alcoholism. After he rejoined, relationships between him and the other members became strained. After initial recording sessions, Coxon left, leaving little of his presence on the finished album. Think Tank is a loose concept album, which Albarn has stated is about "love and politics".[2] Albarn, a pacifist, had spoken out against the invasion of Afghanistan and, after Western nations threatened to invade Iraq, took part in the widespread protests against the war. Anti-war themes are recurrent in the album as well as in associated artwork and promotional videos.

After leaking onto the internet in March, Think Tank was released on 5 May 2003 and entered the UK Albums Chart at number one, making it Blur's fifth consecutive studio album to reach the topspot. The album was later certified Gold. Think Tank also reached the top 20 in many other countries, including Austria, Switzerland, Germany, Norway and Japan. It was their highest charting album in the United States, reaching number 56 on the Billboard 200. The album produced three singles, which charted at number 5, number 18 and number 22 respectively on the UK Singles Chart. After the album was released, Blur announced a world tour with Simon Tong replacing Coxon as a guitarist.

Think Tank was well-received critically, with a score of 83 on Metacritic, which equates to a tag of "universal acclaim".[3] Several critics saw the album as timely, in part due to its being recorded in the Arab world where US and UK policies were unpopular. The album was nominated for Best British Album at the 2004 Brit Awards, and won the Q Album of the Year award. Since its release, Think Tank received a number of accolades listing it as one of the greatest albums of 2003 as well as the decade as a whole. This is also the first blur album to not start off with a single.

Background

Although Blur had been associated with the Britpop movement, they had experimented with different musical styles more recently, beginning with Blur (1997) which had been influenced by Indie rock bands under the suggestion of guitarist Graham Coxon. Since the mid to late 1990's, Blur's members had been working on other projects as well as Blur: Albarn had co-created Gorillaz, a virtual band in 1998 with comic artist, Jamie Hewlett whom Albarn had met through Coxon. Gorillaz' 2001 debut was financially successful and received critical acclaim. Since composing the Blur song, You're So Great, Coxon had started a solo career and as of 2001 had released three solo albums. The members differing musical interests had alienated some of the band members, with Coxon explaining, "we're all very concerned for each other and we do genuinely like each other an awful lot. Because we're into so much different stuff, it becomes daunting."[4] Nevertheless, Coxon, along with Alex James and Dave Rowntree were keen for a new album, whilst Albarn was more reluctant.[5]

Blur's prior album, 13, had made heavy use of experimental and electronic music with the guidance of producer William Orbit. Despite the success of the album and its associated singles, the overall sound of the album had been deemed as "deliberately uncommercial" compared to their previous efforts.[6] Despite the broader musical landscaping which Blur were engaging in, Albarn revealed in a January 2001 interview that he wanted to make a more accessible album again, stating "I'm trying to go back to the kind of songwriting aesthetic I had on (hit album) Parklife. They won't be arranged in the same way at all – they'll just be songs that are accessible to the public." He also revealed his reasoning for this approach, stating that "it's too complicated being anything other than mainstream with Blur. That's where it belongs. We still feel that the mainstream in Britain is not represented well enough by intelligent musicians."[6]

After the September 11th Attacks, a series of controversial military campaigns were launched, known as the War on Terror. In November 2001, shortly after the Invasion of Afghanistan, the MTV Europe Music Awards were held in Frankfurt, where Gorillaz won an award for Best Dance Act.[7] As Albarn and Hewlett walked onto stage to make a speech, Albarn sported a T-shirt with the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament logo on it. In Albarn's speech, he said "So, fuck the music. Listen. See this symbol here, [pointing to the t-shirt] this the symbol for the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament. Bombing one of the poorest countries in the world is wrong. You've got a voice and you have got to do what you can about it, alright?"[8][9][10][11]

In 2002, Iraq was under threat of invasion from western nations. Opposition from the public led to protests being organised by a number of organisations. Albarn, who has described himself as being anti-war, spoke out against the invasion,[12][13] citing the lack of democratic process as an issue.[14][15] Anti-war views had been shared with Albarn's parents and grandparents. His grandfather, Edward Albarn, had died after going on a hunger strike the previous year.[16][17]

Albarn teamed up with Robert "3D" Del Naja of Massive Attack and various campaigns to raise awareness of the potential dangers of the UK's involvement in the war.[14][18] Albarn was due to speak in Hyde Park on the rally in March 2003 when a million people took to the streets of London in protest at the imminent war.[19] In the event, he was too emotional to deliver his speech.[15][17][20][21]

Recording history

Recording sessions for Think Tank started in November 2001 at Albarn's 13 Studio in London. Albarn, James and Rowntree had come to the studio along with Ben Hillier, who explained that "there was tension to begin with. Alex had made some belittling comment about Gorillaz in the press, but there was a 'fuck you' and a 'fuck you' and it was all mates again but for the fact that Graham was missing."[22]

During 2001, Coxon had been battling alcoholism and depression, however, he had failed to tell his bandmates that he could not turn up to the initial session. Despite Coxon's absence, the rest of the band decided to start recording without him.[22] Coxon didn't feature on one of the first songs to be recorded during the sessions, Don't Bomb When You're the Bomb which was released in late 2002 as a limited edition 7" white vinyl.

By January 2002, the rest of the band were mainly recording demos that Albarn had started on a four-track and subsequently transferred into Logic with 13's in-house engineers Tom Girling, Jason Cox and assistant, James Dring. Hillier revealed that "I don't usually work with an engineer, I usually do it all myself, so it was nice – especially nice to have Jason. He's an awful lot more than an engineer, he's worked with the band for years, he knows 13 and the band's equipment inside out. By the end of the four weeks we had 17 songs – quite an astonishing work-rate considering that the band won't work past 6 pm when they're in London."[23] Think Tank's fourth track, "On The Way to the Club", in Albarn's words, "changed dramatically" from the original demo. "Only [Hillier], myself and [Dring were in the studio]", revealed Albarn. "I was just sort of playing around and they were doing something else and the tune came out and the bit of the lyric, so I just went 'can you put a drum beat down really quickly'. So they put down these mad kind of fractious things down and we built it up from there."[24]

Coxon rejoined the rest of the band for recording sessions in February and May 2002, with the foreknowledge that it would be "tense in the studio."[5] Coxon spent, what he described as "awkward afternoons", contributing on the tracks, "Battery in Your Leg", "The Outsider", "Morricone", and "Some Glad Morning."[25] Of his contributions during these sessions, only "Battery in Your Leg" ended up on the final album. The rest of the band reportedly, found problems with Coxon's "attitude" during these sessions,[22] with Coxon himself admitting that he was "probably a little crackers, still. And very energetic".[25] Eventually, Blur's manager, Chris Morrison, asked Coxon to leave on behalf of the rest of the band.[22] The remaining members of Blur decided to carry on recording, Albarn stating that "the spirit of Blur was more important than the individuals."[26]

In June, the band went back into the studio, doing "tracking, overdubs and reworking what we'd already done, and all the time new songs would be popping up – I think we had 28 of them at one point."[23] Even by July, the recordings were "scatty" and "thrown together."[22] Albarn desired to have multiple producers involved in the album, wanting to get a 'name producer' involved.[22] Albarn had previously been in talks with Norman Cook (commonly known as Fatboy Slim) to be involved on the record, although he originally wanted to contribute "just feedback and nothing else."[4][27] Albarn eventually invited him into 13 to try and work with the band, although Cook, contrary to rumours, had never signed on to produce the whole album as his solo career was taking up most of his time.[22] Hillier and the band also spent time working with other producers, including The Dust Brothers who according to Hillier, "did good work but they probably came in a bit early in the process. I don't think we ended up using any of the things they did in the end, but that wasn't a reflection on them at all. It was more a question of them turning up at a point when we weren't quite sure what we were doing, and if anything they showed us that we needed to do a bit more work on the writing." The Neptunes were also reported to be involved at one point.[28]

In August, the remaining members of Blur, along with Hillier, travelled to Morocco. James released a statement on the band's website saying "I suppose the idea at the bottom of this is to escape from whatever ghetto we're in and free ourselves by going somewhere new and exciting."[29] The band settled at Marakesh where they equipped an old barn with a studio.[30] "Damon had been out there to a music festival one weekend and was really excited by it", revealed Hillier. "The musical life in Marrakesh is amazing. Live music is everywhere. It's a very important part of the culture, in a more direct way than it is over here. Here it's all strictly disseminated via radio and records, and DJs and bands. Over there live music can happen anywhere, and usually does. And they'll write songs about current situations all the time and not think twice about it. It's the sort of living folk tradition that we used to have here, and probably still do somewhere."[23]

Albarn claimed that most of the album's lyrics were written "under a cypress tree in Morocco."[31] "They gave us rural cuisine," added James. "Boiled vegetables, mostly. Everyone had the galloping shits for a month and Dave [Rowntree] nearly died. Damon was the only one who didn't get ill and that was because he was so used to Africa. He was wandering around eating handfuls of the nearest tree."[32]

The sessions in Marrakesh produced "Crazy Beat", "Gene by Gene", and "Moroccan Peoples Revolutionary Bowls Club".[30] All of the vocal sessions took place at this time, Albarn revealing that "All of the vocals were sung outside [...] It was nice. When it's nice weather, it's nice to be outside. I think the big studios are a con. They charge people to make less exciting records. That doesn't make any sense to me. I mean, recording as it is now, you don't need studios. You can do it on whatever you want, whenever you want. That's a great liberation that computers and technology have given us. It basically means that it's just going back to where it comes from, which is music on the streets and in the houses."[33]

While in Morocco, Albarn wrote a song about Cook and his partner, Zoë Ball who were having troubles with their relationship.[34] The song started out as a jam session, eventually evolving into "Put It Back Together" which ended up on Fatboy Slim's fourth studio album, Palookaville, which was released in October 2004.[22]

Albarn described the sessions as "[putting] things together that didn't work. We made a lot of mistakes but the ones that we thought worked we kept and put on the album. There's still a few that I'd like to have seen on the record, but it would have turned into a different record. 'Cause a lot of the other stuff was probably a bit rawer but still really interesting. The record may have been a double album and you'd have had the laid back side and the more kind of fractious, difficult side and I think what we wanted was to find the balance between those two."[24]

After the band came back from Morocco, the remaining sessions took place in a barn on National Trust land in Devon. "We were left to our own devices, in a barn, making music," recalled James. "All that happened was the sun came up, it got hot and then it got dark. We were all living in a house next to the barn like The Monkees. We bugged the shit out of each other but, overall, they were happy days. Very life-affirming."[32]

William Orbit, who was the main producer on 13 was also involved in the album's production, with Hillier stating that "we sent a couple of tunes to William to work on in his studio, working round the clock in a computer environment the way he does. He's a nutter and works all night. That was quite an interesting juxtaposition, us doing office hours then going to see William after work, just as he was getting up!"[23] Of Orbit's productions, "Sweet Song" ended up on the album. Coxon's absence also bolstered the role of Alex James and Dave Rowntree who provided backing vocals throughout the album. Rowntree also played the electric guitar on "On the Way to the Club" and provided a rap on a demo version of "Sweet Song".[35] A Moroccan orchestra is featured in the lead single, "Out of Time".[2]

Musical style

"Blur have reinvented themselves as boldly postcolonial popsters. Think Tank's songs aren't merely multicultural, they're multilateral, recorded partly in Morocco and sung in a musical polyglot Hoovered up from stray corners of the empire: aspects of Afrobeat, bits of bhangra, images of Islam. With guitarist Graham Coxon missing in action, the rhythm section of Alex James and Dave Rowntree steps up, and the album shuffles and grooves like Fela Kuti sloshed on gin and tonics."

Despite Albarn stating that he originally wanted to return to their more commercial sound, Think Tank continues the jam-based studio constructions of previous album 13. The album expanded on the use of sampled rhythm loops and brooding, heavy electronic sounds. Almost entirely written by Albarn, Think Tank placed more emphasis on lush backing vocals, simple acoustic guitar, drums, bass guitar, and a variety of other instruments.

""We knew we had to come back with the best thing we'd ever done," observed James. "I think it is. It's next level shit!"[32]

Like many of Blur's previous albums, Think Tank is a loose concept album. Albarn has stated that it is an album about "love and politics",[2][37] stating that "[Unease] forces people to value what they've got. And that, hopefully, will pay dividends and help change the world to a better place. Hopefully. Touch wood."[37] Albarn also stated that the album is about "what are you supposed to do as an artist other than express what is going on around you."[38] Some of the songs are concerned with a sense of paranoia and alienation in British club culture.[citation needed] Damon also cited punk rock music, particularly The Clash, as an inspiration.[28]

The album's opening track, "Ambulance", starts off with a complex drum beat. Sam Bloch of Stylus Magazine praised the song's intro, describing the beat as "an offbeat rhythmic synapse that nearly collapses into itself [...] Heavy electronic drums. A flash. A kick. At first, it's really hard to believe that this is a song, functioning on its own. The beat needs crutches to stand upright."[40] Devon Powers of Pop Matters wrote that "the first bars [...] are stricken with throbbing beats that sound simultaneously futuristic and primitive."[39] Bloch went on to write: "as a low, thunderous bass enters [the listener's] speakers, the whole thing slowly grows. Distinctive African percussion is leisurely incorporated into the bass overtone—it's the darkness in a thunderstorm, the pure, simple fury that comes before a glorious lightning streak."[40]

At 0:52 Albarn's lead vocals come in, repeating the lyrics "I ain't got nothin' to be scared of" in a "gauzy" falsetto. This is accompanied by a "languid" bass groove and backing vocals described by Bloch as "gospel-twinged", as well as a baritone sax line described by Powers as "[cutting] underneath the back-up singers, at an angle—so quirky it feels like Morphine could have played it." As Albarn delivers the next line ("'cause I love you"), a synthesizer kicks in, described by stylus as "illustrious", "otherworldly" and "flooding the song's deathly stomp. But within this death there is love. Albarn makes this clear in the structure of this song." In Albarn's next vocal lines, he drops out of falsetto into "his low swinging monotone". Powers stated that he "croons, carelessly, almost as if he's freestyling. Things change again. They keep changing." Powers speculated that the song was about love but said "it's also a fitting introduction to a record that's such an extreme departure from their past work, and so drastically left field from the garage and post-punk and easily accessible poprock currently drenching the airwaves".[39]

In an XFM radio interview, Albarn spoke on the composition of the track, stating, "I try to do a lot of stuff once I've got the melody and the chord structure. I try to just sing it in one go without thinking about it too much. It comes out a sort of partially formed song and sometimes you're lucky and it comes out almost kind of sort of perfect and sometimes it's just a mess." He stated that this was a case of the former. James revealed that "Ambulance" was "the first song that I thought, right this is Blur again. Like I'm in the right place again. I suppose the lyrics have something to do with that, you know, having nothing to be scared of anymore."[24]

Greenwald claimed that "Out of Time" was "the album's highlight". Describing the song as "failure-soaked" and "heart-stoppingly lovely", Greenwald went on to say that it "perfectly captures the jumble of beauty and dread that defines life under orange alert. "Are we out of time?" Albarn asks, desperate for one last peace march or one last snog." Powers described the song as "a much more straightforward, apace ballad [compared to the previous song]. Dominant in the track are Albarn's unadulterated vocals and steady, simplistic drums, but beyond that are ethereal, hard-to-identify noises. In the middle of the track, an Andalucian string group rears its head, as does a tambourine."[36]

"Crazy Beat" was compared to Song 2, off the band's self titled album. XFM described the song as "Fatboy Slim meets Middle Eastern Punk rock." Powers "energetic, punked-out rocker. But as much as this song might appeal to the neo-DIY set—complete with its jumpy chorus and lively melody—Blur are anything but. If there's one thing Blur are known for, it's lots and lots and lots of production. Norman Cook (aka Fatboy Slim), builds this number with tons of sound, so there's always another active level to uncover." Speaking about the track, Albarn revealed "It started off in such a different way. The nearest thing I could compare it to is a really bad version of Daft Punk. So, we got sick of it and then put in that descending guitar line over it to rough it up a bit."[41] He also stated "It had this sort of mad vocoder ish vocal and the melody was over a real sort of skanky groove and just this almost descending semi tonal guitar. The melody worked over it and it was amazing coz it shouldn't have worked, another little magic moment for us."[24]

Powers claimed that "the best moments of this album are those when vintage Blur styles are evoked with new expertise. The meandering "Good Song" is a beautiful case in point. Acoustic guitar picking is matched with temperate drums and a sweet, steady bass countermelody. Albarn's singing is mostly in his mid-range, falling out as easily as breath. Signature background vocal harmonies are there to brighten up the track, but their muted nature doesn't descend into campiness. What's also new is the expert use of electronic noises and drumbeats to fatten the sound." Albarn said "well, that was originally called 'De La Soul' on our huge list of songs, half finished ideas. It was called 'De La Soul you know, right until the end. And I just always thought it was a good song and just called it 'Good Song'. I love that, I love the sort of intimacy of it and I just think everyone really played gently on it, the melodies. It was a good melody."[24]

"On The Way to the Club" was described by Albarn as "a hangover song which we sort of write from time to time." Albarn also said that "it's definitely got a very individual sound. Someone said that it's a sort of revived Screamadelica. Yeah, it's kind of the good intentions of which you participate in revelry and then actually the reality of it."[24]

"Brothers and Sisters" was one of the last additions to the album. "It was a kind of track that took quite a different direction for most of its life", revealed Rowntree. "...And then right at the end we switched about and took it in a different direction, it wasn't quite so dark." "It sounded more like The Velvet Underground when we started", claimed Albarn. "It was too overtly about one thing. It was too druggy, in a way, which is a kind of weird thing, 'cause the song is all about drugs so I think we just pushed ourselves a bit more with it and gave it a lot more space – countered by the list and the list was kind of sort of inspired by the life of JFK and his need to have 28 drugs everyday of his Presidency just to keep him functioning."[24]

Albarn described "Caravan" as "a kind of song that you could play anywhere. And I mean I remember we just finished it and when everyone left to go back to London, I went down to Mali for a couple of days 'cause Honest Jon's [were] still working with musicians and stuff. I was sitting in a mango grove with a wild turkey and had a little CD player and I put it on there. It was just nice seeing everyone sitting around getting stoned to it. It was nice, 'cause the guitar is very, much inspired by Afel; a great Malian tradition of blues guitar."[24][failed verification] "I think this one's about the sun going down, for me", James claimed. "That was like a perfect studio moment; sitting on top of a strange barn in the Moroccan desert listening to Damon do a vocal and it a was a perfectly still time of day and the sun was perfectly red and there was just an immense sense of calm and this music."[24]

Albarn claimed that "Sweet Song" was inspired by Coxon. Explaining the habit of putting 'song' in the title, Albarn stated that it was "another African thing that I've picked up. They do call things like 'Tree Song'. You know what I mean; they give it something quite simple. It's not, it doesn't have an agenda so much, it's offered out as a nice bit of music to everyone and that's something that has changed massively in my life, I don't see the ownership of things quite so strongly anymore."[24]

There is a hidden track, "Me, White Noise" in the pregap before track 1 on some CD copies. The song guest features Phil Daniels, who previously appeared on Parklife, on vocals. Japanese versions of the album feature the song at track 30, after silent tracks at index points 15–29. On the Blur 21 edition, the hidden track is assigned to track number 14.

The case contains a Parental Advisory logo in some regions, because "Brothers and Sisters" contains many drug references. Also, the hidden track "Me, White Noise" is one of the few Blur songs to contain an expletive.

Artwork and packaging

The album cover was stenciled by the graffiti artist Banksy.[42] Despite Banksy stating that he normally avoids commercial work,[43][44] he later defended his decision to do the cover, saying: "I've done a few things to pay the bills, and I did the Blur album. It was a good record and [the commission was] quite a lot of money. I think that's a really important distinction to make. If it's something you actually believe in, doing something commercial doesn't turn it to shit just because it's commercial. Otherwise you've got to be a socialist rejecting capitalism altogether, because the idea that you can marry a quality product with a quality visual and be a part of that even though it's capitalistic is sometimes a contradiction you cant live with. But sometimes it's pretty symbiotic, like the Blur situation.'[44] The album's cover art sold at auction in 2007 for £75,000.[45] The fold out booklet of the album features the text "Celebrity Harvest" which was the working name for a proposed, but ultimately unmade Gorillaz film.

The artwork for Green Day's 2009 album, 21st Century Breakdown, was compared to Think Tank's cover.[46] However, cover artist, Sixten, claimed that the couple on the cover were "just friends of a friend at a party in Eskilstuna, Sweden" and explained that a mutual friend snapped a picture of the pair kissing.[47]

Release

Prior to the album's official release, it was leaked onto the internet.[48] Rowntree said "I'd rather it gushed"[49] and "I'm rabidly pro the internet and as many people hearing our albums as possible. If it hadn't been leaked by someone we probably would've leaked it ourselves".[50] Albarn speculated that the leak helped the reception of their live shows, due to the songs' lyrics being more familiar to the audience.

Commercial performance

The album debuted in the USA at number 56 with first week-sales of 20,000, becoming then the highest peak of any Blur album in the US.[51] It has sold 94,000 copies in the US as of April 2015.[52]

In the UK, the album debuted at the top spot, becoming their fifth consecutive number one album. The album remained in the top 10 for three weeks and the top 75 for a total of eight weeks, lacking the longevity and sales success of their previous releases.[53]

Critical reception

| Aggregate scores | |

|---|---|

| Source | Rating |

| Metacritic | 83/100[3] |

| Review scores | |

| Source | Rating |

| AllMusic | |

| Entertainment Weekly | C+[55] |

| The Guardian | |

| Los Angeles Times | |

| NME | 8/10[58] |

| Pitchfork Media | 9.0/10[59] |

| Q | |

| Rolling Stone | |

| Spin | A[36] |

| Uncut | |

Think Tank received rave reviews from contemporary music critics. At Metacritic, which assigns a normalised rating out of 100 to reviews from mainstream critics, the album received an average score of 83, which indicates "universal acclaim", based on 26 reviews[3] Drowned in Sound writer Andrew Future deemed the album as "a genuine pleasure to behold" and whilst stating that previous albums Blur and 13 were "full of jump-start arrangements and fractured experimentalism", he described Think Tank as being "lush in melody, flowing in windswept electronica with a myriad of bombastic orchestral backing one minute, before retracting into cocoons of melancholic and clustered acoustics the next." Playlouder called the album "an extraordinary record that pushes boundaries and sets new standards."

"The beat-driven tracks," observed Steve Lowe in Q, "veer towards the arty, white-boy-with-beatbox line of Talking Heads and The Clash (actually, the low-slung hip-pop of 'Moroccan Peoples Revolutionary Bowls Club' even recalls Big Audio Dynamite). Only the trudging, tedious six-minute squib 'Jets' really needs taking back to the shops."[32]

According to Acclaimed Music, Think Tank is the 783rd most critically acclaimed album of all time.[63][64] Deviating from critical consensus, Stephen Thomas Erlewine of AllMusic wrote: "This is the sound of Albarn run amuck, a (perhaps inevitable) development that even voracious Blur supporters secretly feared could ruin the band — and it has." He described Think Tank as a "lousy album" on which the few strong tracks are "severely hurt by Coxon's absence".[54]

Albarn in 2015 said of Think Tank: "It's... got some real stinkers on it – there's some bollocks on there."[65]

Accolades

Blur received a number of awards and nominations for Think Tank. At the 2003 Q Awards, Think Tank won the award for Best Album.[66][67] This was the third time the band had received this award, previously winning in 1994 and 1995 for Parklife and The Great Escape retrospectively.[67] Blur also received nomination for Best Act in the World Today and, along with Ben Hillier, were nominated in the Best Producer category.[66] The album also won in the Best Album category at the South Bank Show Awards in 2004[66][68] and was nominated in a similarly titled category at the Danish Music Awards the same year. Think Tank was nominated for Best British Album at the 2004 Brit Awards.[69] The promo videos for Out of Time and Good Song also won several awards.[66]

At the end of the year, The Observer listed Think Tank as the best album of 2003, Miranda Sawyer writing that, "Think Tank is the band's first warm album. They have hopped genres in the past, from baggy to mod to pop to grunge to art-rock, but the sound has always stayed urban, Western, cool. Think Tank is none of these things. It's all over the place, and that place is foreign. Odd noises, strange instruments, keening vocals; its tunes wind themselves around your heart like drifting smoke. They waft in from faraway lands; trail and trickle their scent across your life. It is the most peculiar stuff that stays with you; "Ambulance"'s slurred symphony; "Caravan"'s star-speckled wonder."[70]

| Publication | Country | Accolade | Year | Rank |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bang | UK | Albums of the Year[71] | 2003 | 3 |

| BBC | UK | Albums of the Year[72] | 2003 | * |

| Drowned in Sound | UK | Albums of the Year[73] | 2003 | 43 |

| Eye Weekly | Canada | Albums of the Year (Critics Poll) | 2003 | 23 |

| Albums of the Year (Writers) | 11 | |||

| Fnac | France | The 1000 Best Albums of All Time[74] | 2008 | 799 |

| Les Inrockuptibles | France | The 100 Albums of the 2000s | 2010 | 7 |

| Mojo | UK | Albums of the Year[75] | 2003 | 3 |

| NME | UK | Albums of the Year[76] | 2003 | 21 |

| Top 100 Albums of the 2000s[77] | 2009 | 20 | ||

| The Observer | UK | Albums of the Year[70] | 2003 | 1 |

| Playlouder | UK | Albums of the Year | 2003 | 18 |

| PopMatters | US | Albums of the Year | 2003 | 7 |

| Q | UK | Albums of the Year[78] | 2003 | 2 |

| Top 100 Albums of the 2000s | 2009 | 59 | ||

| Rolling Stone | US | Albums of the Year | 2003 | * |

| Rolling Stone | France | The 20 Albums of the 2000s | 2010 | * |

| Rough Trade | UK | Albums of the Year | 2003 | 86 |

| Slant Magazine | US | Top 250 Albums of the 2000s[79] | 2010 | 145 |

| Spin | US | Albums of the Year[80] | 2003 | 16 |

| Uncut | UK | Albums of the Year[81] | 2003 | 62 |

| Top 150 Albums of the 2000s[82] | 2009 | 22 |

Tour

After the album's release, Blur went on a world tour with Simon Tong replacing Coxon. However, Albarn later revealed that he felt the live shows were "rubbish" and bassist, Alex James admitted that touring was not the same without Coxon. [5][25]

Since Blur's reunion with Coxon in 2009, the album has mostly been removed from Blur's setlist, with the exception of "Out of Time" (in a new arrangement with additional guitar parts by Coxon) and occasional performances of "Battery in Your Leg" in 2009 and "Caravan" in 2015.

Track listing

All lyrics are written by Damon Albarn. All music by Albarn, Alex James, Dave Rowntree except where noted

| No. | Title | Length |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Ambulance" | 5:09 |

| 2. | "Out of Time" | 3:52 |

| 3. | "Crazy Beat" | 3:15 |

| 4. | "Good Song" | 3:09 |

| 5. | "On the Way to the Club" (Albarn, James Dring, James, Rowntree) | 3:48 |

| 6. | "Brothers and Sisters" | 3:47 |

| 7. | "Caravan" | 4:36 |

| 8. | "We've Got a File on You" | 1:03 |

| 9. | "Moroccan Peoples Revolutionary Bowls Club" | 3:03 |

| 10. | "Sweet Song" | 4:01 |

| 11. | "Jets" (Albarn, James, Rowntree, Mike Smith) | 6:25 |

| 12. | "Gene by Gene" | 3:49 |

| 13. | "Battery in Your Leg" (Albarn, Coxon, James, Rowntree) | 3:20 |

The song "Me, White Noise" is a hidden track placed in either the pregap of the first track or at the end of "Battery in Your Leg" after about five minutes of silence.

Personnel

Blur

- Damon Albarn – vocals, backing vocals, guitar, piano, keyboards, producer

- Alex James – bass guitar, backing vocals, production

- Dave Rowntree – drums, backing vocals, guitar on "On the Way to the Club", production

Additional musicians and production

- Bezzari Ahmed – rabab

- Moullaoud My Ali – oud

- Mohamed Azeddine – oud

- Norman Cook – producer (Track 3 & 12)

- Jason Cox – production assistance, engineer

- Graham Coxon – guitar on "Battery in Your Leg"

- Phil Daniels – backing vocals on "Me, White Noise"

- James Dring – engineer, programming

- Ben Hillier – producer, engineer, percussion

- Gueddam Jamal – cello, violin

- Abdellah Kekhari – violin

- Ait Ramdan El Mostafa – kanoun

- Desyud Mustafa – orchestral arrangement

- El Farani Mustapha – tere

- Dalal Mohamed Najib – darbouka

- Hijaoui Rachid – violin

- M. Rabet Mohamid Rachid – violin

- Mike Smith – saxophone

- Kassimi Jamal Youssef – oud

- William Orbit – producer (Track 10)

Charts and certifications

Weekly charts

|

Certifications

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

References

- ^ "Blur – Think Tank". AllMusic. Retrieved 6 November 2014.

- ^ a b c "Blur "Think" Up New Album". 25 February 2003. Retrieved 19 November 2011.

- ^ a b c "Reviews for Think Tank by Blur". Metacritic. Retrieved 18 November 2015.

- ^ a b "Coxon goes ape over Gorillaz!". Dotmusic.com. 30 July 2001.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ a b c No Distance Left To Run. Pulse films. 2010

- ^ a b Grant, Kieran (20 January 2001). "Gorillaz in his midst". Jam! Showbiz. Canada: canoe.ca. Retrieved 3 October 2012.

Both criticized and praised for being deliberately uncommercial..." "No, I'm trying to go back to the kind of songwriting esthetic I had on (hit album) Parklife. They won't be arranged in the same way at all – they'll just be songs that are accessible to the public. It's too complicated being anything other than mainstream with Blur. That's where it belongs. We still feel that the mainstream in Britain is not represented well enough by intelligent musicians.

- ^ "Brits take six MTV Europe awards". The Guardian. 9 November 2001. Retrieved 9 October 2012.

- ^ "Gorillaz – EMA's 2001 ("Best Dance" Award)". YouTube. Retrieved 9 October 2012.

- ^ "Damon Albarn and Robert del Naja interview, Rock Crusaders". The Independent on Sunday. 9 February 2003.

- ^ "Stars celebrate MTV success". Daily Mail. 2001. Retrieved 9 October 2012.

- ^ "MTV winners Gorillaz protest U.S. bombing". Jam! Showbiz. Canada: canoe.ca. 9 November 2001. Retrieved 9 October 2012.

- ^ "WAR ON WAR!". NME. 20 August 2002. Retrieved 15 September 2012.

- ^ Anderson, Errol. "10 Things You Never Knew About Damon Albarn". Retrieved 19 November 2011.

- ^ a b "Damon Albarn's Anti-War Protest". XFM. 2 July 2003. Retrieved 15 September 2012.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ a b Kennard, Matt (24 November 2008). "An interview: Damon Albarn on the Gorillaz, fatherhood, the war in Iraq, and going out". The Comment Factory. Retrieved 15 September 2012.

- ^ "LINCOLNSHIRE PEACE COMMUNITY". BBC Inside Out. 6 September 2004. Retrieved 15 September 2012.

- ^ a b Mulholland, Gary (21 September 2003). "Special relationships". The Observer. Retrieved 15 September 2012.

- ^ Smith, Martin. "Musicians who won't be silenced". The Socialist Worker. Retrieved 15 September 2012.

- ^ "10 Things You Never Knew About Damon Albarn". Retrieved 19 November 2011.

- ^ "Deconstructing Damon". The Scotsman. 16 November 2003.

- ^ Elbel, Jeff (1 June 2003). "Blur – Think Tank – Review". Paste. Retrieved 17 September 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Stubbs, Dan (April 2012). "Blur – Think Tank (2003): The Album That Almost Destroyed Them...". Q. 20 Greatest Album Stories Ever: 42–45.

- ^ a b c d Greeves, David (July 2003). "Ben Hillier Recording Blur, Tom McRae & Elbow". Sound on Sound. Retrieved 29 September 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "Blur 'Think Tank' Track By Track". XFM. 2 July 2003. Archived from the original on 6 June 2011. Retrieved 20 October 2012.

- ^ a b c Harris, John (13 June 2009). "It's been strong medicine the last few weeks". The Guardian: 1. Retrieved 12 September 2012.

- ^ Video on YouTube

- ^ "Girls and Fatboys". NME. 7 March 2001. Retrieved 28 October 2012.

- ^ a b "Damon: 'Blur got away from American guitar sound'". Blitz. 2002.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ "THE GREAT ESCAPE?". NME. Retrieved 9 November 2012.

- ^ a b "Blur – Think Tank – album info". Vblurpage.com. 5 May 2003. Retrieved 16 February 2011.

- ^ Lester, Paul (25 April 2003). "This dysfunctional family". The Guardian. Retrieved 20 October 2012.

- ^ a b c d Q, May 2003

- ^ "A True Story about Blur, Survival and Laughing at Doomsday". Filter. May 2003.

- ^ "Zoe Ball and Fatboy Slim 'to split'". BBC News. 18 January 2003. Retrieved 20 May 2010.

- ^ "Unreleased Blur Tracks". Vblurpage.com. Retrieved 16 February 2011.

- ^ a b c Greenwald, Andy (June 2003). "Blur, 'Think Tank' (Virgin)". Spin. 19 (6): 100. Retrieved 18 November 2015.

- ^ a b "A True Story about Blur, Survival and Laughing at Doomsday". Filter. May 2003.

- ^ Brown, Chris (21 November 2003). "Blurred vision". Daily Post.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ a b c Powers, Devon (9 May 2003). "Blur: Think Tank". PopMatters. Retrieved 16 February 2011.

- ^ a b Bloch, Sam (1 September 2003). "Blur – Think Tank – Review". Stylus Magazine. Retrieved 16 February 2011.

- ^ Wiederhorn, Jon (24 April 2003). "Blur Reinvent Themselves With Fatboy Slim, Go 'Crazy' On New Record". MTV. Retrieved 3 October 2012.

- ^ "Banksy artwork sets new benchmark". BBC News. 26 October 2006. Retrieved 20 June 2009.

- ^ Hattenstone, Simon (17 July 2003). "Something to spray". The Guardian: 10. Retrieved 9 September 2012.

- ^ a b Ellsworth-Jones, Will (2012). Banksy: The Man Behind The Wall. Aurum Press Ltd. p. 200.

- ^ "Elusive artist Banksy sets record price". Reuters UK. 25 April 2007. Retrieved 9 May 2008.

- ^ Lewis, Luke (10 February 2009). "Green Day Artwork – Have They Stolen From Blur?". NME. Retrieved 12 November 2012.

- ^ "Green Day artist reveals story behind new album cover". NME. 11 February 2009. Retrieved 20 June 2009.

- ^ "Should music downloads be free?". BBC News. 12 July 2006. Retrieved 11 October 2012.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "Rock star says piracy battle is lost". The Register. out-law.com. 15 June 2007.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ "X-clusive: Blur's Secret Album Track Uncovered". XFM. 2 July 2003. Retrieved 11 October 2012.

The gigs are going down really well. Helped by the fact that it's been on the internet for two months and everybody knows all the words to every song, which is weird. The idea of playing a totally 'cold' gig doesn't really exist anymore as everyone has all the music they want to hand.

- ^ Emily White (7 May 2015). "Florence + The Machine Tops Rock Chart, Blur Debuts". Billboard.

- ^ "Upcoming Releases". Hits Daily Double. HITS Digital Ventures. Archived from the original on 25 April 2015.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|website=(help) - ^ "Blur – Think Tank". Retrieved 12 February 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Erlewine, Stephen Thomas. "Think Tank – Blur". AllMusic. Retrieved 18 November 2015.

- ^ Brunner, Rob (9 May 2003). "Think Tank". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved 18 November 2015.

- ^ Petridis, Alexis (2 May 2003). "Blur: Think Tank". The Guardian. Retrieved 8 February 2016.

- ^ Hochman, Steve (18 May 2003). "Quick spins: Blur 'Think Tank' (EMI)". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 18 November 2015.

- ^ Needham, Alex. "Blur: Think Tank". NME. Retrieved 16 February 2011.

- ^ DiCrescenzo, Brent (5 May 2003). "Blur: Think Tank". Pitchfork Media. Retrieved 25 November 2012.

- ^ "Blur: Think Tank". Q (202): 96. May 2003.

- ^ Walters, Barry (22 April 2003). "Think Tank". Rolling Stone. Retrieved 25 May 2012.

- ^ "Blur: Think Tank". Uncut (73): 90. June 2003.

- ^ "Blur". Acclaimed Music. Retrieved 16 February 2011.

- ^ "Think Tank". Acclaimed Music. 19 December 2003. Retrieved 16 February 2011.

- ^ [1]

- ^ a b c d The awards Blur have won or got nominated for

- ^ a b "The Q Awards". everyHit.com. Retrieved 13 October 2012.

- ^ "Blur News – Blur win South Bank Show Award – Jan 28, 2004". Vblurpage.com. 28 January 2004. Retrieved 6 April 2014.

- ^ "The BRITs 2004". Brit Awards. Retrieved 20 September 2012.

- ^ a b Sawyer, Miranda (14 December 2003). "Albums of 2003". The Observer. Retrieved 14 October 2012.

- ^ "2003 End of year lists". Retrieved 14 October 2012.

- ^ "Best Albums of 2003". BBC Collective. Retrieved 13 October 2012.

- ^ Adams, Sean (9 December 2003). "DiS Staff Top 75 Albums of 2003". Drowned in Sound. Retrieved 13 October 2012.

- ^ "Les 1000 CD des disquaires de la fnac". Retrieved 14 October 2012.

- ^ "Mojo Albums of the Year 2003". Retrieved 14 October 2012.

- ^ "NME Albums of 2003". Retrieved 13 October 2012.

- ^ "Top 100 Greatest Albums of the Decade".

- ^ "Q magazine Recordings of the Year". Retrieved 15 October 2012.

- ^ "Rest of the Best of the Aughts: Albums & Singles (#101 – 250)". Slant Magazine. Retrieved 13 October 2012.

- ^ "Spin End of Year Lists 2003".

- ^ "Uncut Albums of the Year 2003". Retrieved 14 October 2012.

- ^ "Uncut's Albums of the Decade: Part three – The Top 50!". Uncut. Retrieved 14 October 2012.

- ^ "Australian chart positions". australian-charts.com. Retrieved 16 October 2012.

- ^ "Austrian chart positions". austriancharts.at. Retrieved 16 October 2012.

- ^ Steffen Hung. "Blur – Think Tank". swisscharts.com. Retrieved 6 April 2014.

- ^ "Dutch chart positions". dutchcharts.nl. Retrieved 16 October 2012.

- ^ Billboard – Google Books. Books.google.co.uk. Retrieved 6 April 2014.

- ^ "French chart positions". lescharts.com. Retrieved 16 October 2012.

- ^ "German album positions". musicline.de. Retrieved 16 October 2012.

- ^ "ブラーのCDアルバムランキング". Oricon Style. Retrieved 16 October 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ Steffen Hung. "Discography Blur". irishcharts.com. Retrieved 6 April 2014.

- ^ "New Zealand chart positions". charts.org.nz. Retrieved 16 October 2012.

- ^ "Norwegian chart positions". norwegiancharts.com. Retrieved 16 October 2012.

- ^ "Portuguese chart positions". portuguesecharts.com. Retrieved 16 October 2012.

- ^ Salaverri, Fernando (September 2005). Sólo éxitos: año a año, 1959–2002 (1st ed.). Spain: Fundación Autor-SGAE. ISBN 84-8048-639-2.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ "Swedish chart positions". swedishcharts.com. Retrieved 16 October 2012.

- ^ "Swiss chart positions". hitparade.ch. Retrieved 16 October 2012.

- ^ "British chart positions". chartstats.com. Retrieved 16 October 2012.

- ^ "Blur Album & Song Chart History". Billboard. Retrieved 16 October 2012.

- ^ THE FIELD id (chart number) MUST BE PROVIDED for NEW ZEALAND CERTIFICATION.

- ^ "British album certifications – Blur – Think Tank". British Phonographic Industry. Retrieved 9 June 2012. Select albums in the Format field. Select Gold in the Certification field. Type Think Tank in the "Search BPI Awards" field and then press Enter.

External links

- Think Tank at YouTube (streamed copy where licensed)