Three-child policy

The three-child policy (Chinese: 三孩政策; pinyin: Sānhái Zhèngcè), whereby a couple can have three children, is a family planning policy in the People's Republic of China.[1][2] The policy was announced on 31 May 2021 at a meeting of the Politburo of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), chaired by CCP General Secretary Xi Jinping, on population aging.[3][4]

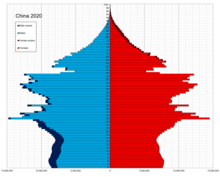

The announcement came after the release of the results of the Seventh National Population Census, which showed that the number of births in mainland China in 2020 was only 12 million, the lowest number of births since 1960, and the further aging of the population, against which the policy was born.[5] This was the slowest population growth rate China experienced.[6] The state-owned Chinese news agency, Xinhua, stated that this policy would be accompanied by supportive measures to maintain China's advantage in human labor.[3] However, some Chinese citizens expressed dissatisfaction with the policy, as they would be unable to raise children due to the high cost of living in China relative to the income.[7][4]

The policy was adopted by the Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party and State Council of the People's Republic of China in June 2021 and announced in July.[8] In August, the Standing Committee of the National People's Congress amended the Population and Family Planning Law,[9] allowing each couple to have three children and cancelling restrictive measures including fines for couples having more children than permitted.[10][11]

Background

[edit]

Beginning in 1979, China implemented the one-child policy, which stipulated that a couple could only have one child, resulting in a declining new population and a rapidly aging society. In order to slow down the trend of population aging, in 2015, the CCP officially launched the two-child policy, which relaxed the birth restrictions. However, the policy did not result in the expected wave of births, and the pregnancy rate among young women continued to decline, experiencing a third consecutive year of decrease.[12] In this regard, during the 2020 National People's Congress (NPC) session, NPC deputy Huang Xihua suggested removing the penalty policy for having more than three children.[13] Previously, the fine, called a "social upbringing fee" or "social maintenance fee", was the punishment for the families having more than one child. According to the policy, the families violating the law brought the burden to the whole society. Therefore, the social maintenance fee was used for the operation of local governments.[14]

According to Reuters, as of late 2020, people were being fined 130,000 yuan ($20,440) for having a third child.[15]

Reactions

[edit]Although the CCP government had high expectations for the new policy,[16] in a 2021 online poll conducted by the offical state news agency Xinhua on its Weibo account, using the hashtag #AreYouReady for the new three-child policy, about 29,000 out of 31,000 respondents stated they would "never consider it."[15]

Moody's, a bond credit rating agency, said the new three-child policy is unlikely to boost birthrate and the aging will remain a credit-negative constraint for China.[17] A January 2022 study suggested allowing a third child would not significantly boost fertility in the short term.[18]

In January 2023, the government of Sichuan Province announced that it had abolished the three-child policy completely, allowing parents in Sichuan to legally have as many children as they want.[19][20]

According to report, the data released in October 2023 by China's National Health Commission show that 15% of the 9.56 million newborns in 2022 were a family's third child, up only 0.5% from 2021.[21]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "China announces three-child policy, in major policy shift". India Today. Beijing. Reuters. 2021-05-31. Archived from the original on 2021-11-04. Retrieved 2021-05-31.

- ^ "China allows couples to have three children". BBC News. 2021-05-31. Archived from the original on 2021-06-09. Retrieved 2021-05-31.

- ^ a b "China introduces three-child policy in response to ageing population". www.abc.net.au. 2021-05-31. Archived from the original on 2021-05-31. Retrieved 2021-05-31.

- ^ a b Wee, Sui-Lee (2021-05-31). "China Says It Will Allow Couples to Have 3 Children, Up From 2". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 2021-11-04. Retrieved 2021-05-31.

- ^ "三孩生育政策来了". 新华网. Archived from the original on 2021-06-07. Retrieved 2021-05-31.

- ^ "China announces three-child policy, in major policy shift". The Japan Times. 2021-05-31. Archived from the original on 2021-05-31. Retrieved 2021-05-31.

- ^ "Cost of Living in China". www.numbeo.com. Archived from the original on 2021-10-06. Retrieved 2021-10-06.

- ^ "Xinhua Headlines: China unveils details of three-child policy, support measures – Xinhua | English.news.cn". www.xinhuanet.com. Archived from the original on 2023-06-06. Retrieved 2022-12-07.

- ^ "China: Three-Child Policy Becomes Law, Social Maintenance Fee Abolished". Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. 20540 USA. Archived from the original on 2024-03-11. Retrieved 2024-03-17.

- ^ "China Focus: China adopts law amendment allowing couples to have 3 children". www.xinhuanet.com. Archived from the original on 2022-12-07. Retrieved 2022-12-07.

- ^ "China: Three-Child Policy Becomes Law, Social Maintenance Fee Abolished". Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. 20540 USA. Archived from the original on 2022-12-07. Retrieved 2022-12-07.

- ^ Wee, Sui-Lee; Myers, Steven Lee (2020-01-17). "China's Birthrate Hits Historic Low, in Looming Crisis for Beijing". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 2021-11-04. Retrieved 2021-06-01.

- ^ "全国人大代表黄细花:建议取消生育限制,取消生三孩以上处罚". 澎湃新闻. Archived from the original on 2021-06-03. Retrieved 2021-06-01.

- ^ Jiang, Quanbao; Liu, Yixiao (2016). "Low fertility and concurrent birth control policy in China". The History of the Family. 21 (4): 551–577. doi:10.1080/1081602X.2016.1213179. ISSN 1081-602X. S2CID 157905310.

- ^ a b Stanway, David; Munroe, Tony (June 1, 2021). "Three-child policy: China lifts cap on births in major policy shift". Reuters. Archived from the original on November 7, 2023. Retrieved March 16, 2024.

- ^ "China releases decision on third-child policy, supporting measures". The State Council of the People's Republic of China. July 20, 2021. Archived from the original on March 16, 2024. Retrieved March 16, 2024.

- ^ "China's three-child policy unlikely to boost birthrate – Moody's". Reuters. June 6, 2021. Archived from the original on October 24, 2023. Retrieved March 16, 2024.

- ^ Attané, Isabelle (January 2022). "China's new three-child policy: What effects can we expect?". Population Societies. 596 (1): 1–4. Archived from the original on 7 December 2022. Retrieved 7 December 2022.

- ^ Fisher, Megan (30 January 2023). "Sichuan: Couples in Chinese province allowed to have unlimited children". BBC. Archived from the original on 22 August 2023. Retrieved 29 October 2023.

- ^ "Why One of China's Largest Provinces Is Lifting Birth Limits—Even for Unmarried Parents". TIME. 2023-02-02. Archived from the original on 2024-03-16. Retrieved 2024-03-16.

- ^ Feng, Jenny (2023-10-17). "China's three-child policy isn't leading to a surge in births, data shows". The China Project. Archived from the original on 2024-03-16. Retrieved 2024-03-16.