1824 United States elections

| ← 1822 1823 1824 1825 1826 → Presidential election year | |

| Incumbent president | James Monroe (Democratic-Republican) |

|---|---|

| Next Congress | 19th |

| Presidential election | |

| Partisan control | Democratic-Republican hold |

| Electoral vote | |

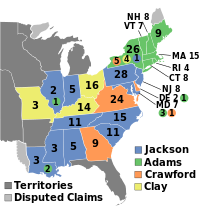

| John Quincy Adams (DR) | 84[1] |

| Andrew Jackson (DR) | 99 |

| William H. Crawford (DR) | 41 |

| Henry Clay (DR) | 37 |

| |

| 1824 presidential election results. Blue denotes states won by Jackson, orange denotes those won by Crawford, green denotes those won by Adams, light yellow denotes those won by Clay. Numbers indicate the number of electoral votes allotted to each state. | |

| Senate elections | |

| Overall control | Jacksonian gain |

| Seats contested | 16 of 48 seats[2] |

| Net seat change | Jacksonian +25[3] |

| House elections | |

| Overall control | Anti-Jacksonian gain |

| Seats contested | All 213 voting members |

| Net seat change | Anti-Jacksonian +22[3] |

The 1824 United States elections elected the members of the 19th United States Congress. It marked the end of the Era of Good Feelings and the First Party System. The divided outcome in the 1824 presidential contest reflected the renewed partisanship and emerging regional interests that defined a fundamentally changed political landscape. The bitterness that followed the election ensured political divisions would be long-lasting and facilitated the gradual emergence of what would eventually become the Second Party System. Members of the Democratic-Republican Party continued to maintain a dominant role in federal politics, but the party became factionalized between supporters of Andrew Jackson and supporters of John Quincy Adams. The Federalist Party ceased to function as a national party, having fallen into irrelevance following a relatively strong performance in 1812.

In the first close presidential election since the 1812 election, four major candidates ran, all of whom were members of the Democratic-Republican Party. The Democratic-Republicans had largely been successful in fielding only one presidential candidate in previous elections (except in 1812), but the breakdown of the congressional nominating caucus and a lack of meaningful opposition from the Federalists allowed for a multi-candidate field. Senator Andrew Jackson from Tennessee, Secretary of State John Quincy Adams, Secretary of the Treasury William Crawford, and Speaker of the House Henry Clay all received electoral votes. With no candidate receiving a majority of the electoral vote, the House chose among the three candidates (Jackson, Adams, and Crawford) with the most electoral votes. Although Jackson won a plurality of electoral and popular votes, the House elected Adams as president.[4] Despite the chaos in the presidential election, John C. Calhoun won the vice presidency with a majority of electoral votes.

The 1824 presidential election was the only time that the House elected the president under the terms of the Twelfth Amendment, and the only time that the winner of the most electoral votes did not win the presidency. This was the first occasion where the candidate who won the popular vote did not win the presidency. Adams's victory ended the Virginia dynasty of presidents, but continued the trend of the incumbent secretary of state winning election as president.

In the House, Democratic-Republicans continued to command a dominant majority. Supporters of Adams narrowly outnumbered supporters of Jackson.[5] John W. Taylor, who would later join Adams's National Republicans, was elected Speaker of the House.

In the Senate, Democratic-Republicans continued to command a dominant majority. Supporters of Jackson narrowly outnumbered supporters of Adams.[6]

See also

[edit]- 1824 United States presidential election

- 1824–1825 United States House of Representatives elections

- 1824–1825 United States Senate elections

References

[edit]- ^ As no presidential candidate won a majority of the electoral vote, the House of Representatives held a contingent election. Adams won that contingent election.

- ^ Not counting special elections.

- ^ a b Congressional seat gain figures only reflect the results of the regularly scheduled elections, and do not take special elections into account.

- ^ "1824 Presidential Election". The American Presidency Project. Retrieved June 25, 2014.

- ^ "Party Divisions of the House of Representatives". United States House of Representatives. Retrieved June 25, 2014.

- ^ "Party Division in the Senate, 1789-Present". United States Senate. Retrieved June 25, 2014.