User:EnergyAnalyst1/sandbox5

Proposed edits to "Energy in Russia"

Introduction

[edit]Energy in Russia describes energy and electricity production, consumption and export from Russia. Energy policy of Russia describes the energy policy in the politics of Russia more in detail. Electricity sector in Russia is the main article of electricity in Russia.

Energy consumption across Russia in 2020 was 7,863 TWh.[1] Russia is a leading global exporter of oil and natural gas[2] and is the fourth highest greenhouse emitter in the world. As of September 2019, Russia adopted the Paris Agreement [3] In 2020, CO2 emissions per Capita were 11.2 tCO2.[4]

Overview

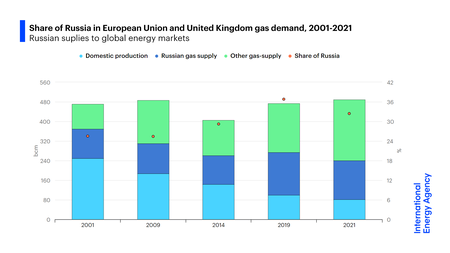

[edit]Russia has been widely described as an energy superpower.[5] It has the world's largest proven gas reserves,[6] the second-largest coal reserves,[7] the eighth-largest oil reserves,[8] and the largest oil shale reserves in Europe.[9] Russia is also the world's leading natural gas exporter,[10] the second-largest natural gas producer,[11] and the second-largest oil producer and exporter.[12][13] Russia's oil and gas production has led to deep economic relationships with the European Union, China, and former Soviet and Eastern Bloc states.[14][15] For example, over the last decade, Russia's share of supplies to total European Union (including the United Kingdom) gas demand increased from 25% in 2009 to 32% in the weeks before the Russian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022.[15] Russia relies heavily on revenues from oil- and gas-related taxes and export tariffs, which accounted for 45% of its federal budget in January 2022.[16]

Russia is the world's fourth-largest electricity producer,[17] and the ninth-largest renewable energy producer in 2019.[18] It was also the world's first country to develop civilian nuclear power, and to construct the world's first nuclear power plant.[19] Russia was also the world's fourth-largest nuclear energy producer in 2019,[20] and was the fifth-largest hydroelectric producer in 2021.[21]

Natural gas

[edit]Russia is the world’s second-largest producer of natural gas, behind the United States, and has the world’s largest gas reserves. Russia is the world’s largest gas exporter. Gazprom and Novatek are Russia’s main gas producers, but many Russian oil companies, including Rosneft, also operate gas production facilities. Gazprom, which is state-owned, is the largest gas producer, but its share of production has declined over the past decade, as Novatek and Rosneft have expanded their production capacity. However, Gazprom still accounted for 68% of Russian gas production in 2021. Historically, production was concentrated in West Siberia, but investment has shifted in the past decade to Yamal and Eastern Siberia and the Far East, as well as the offshore Arctic.[2][15][14]

Russia also has a wide-reaching gas export pipeline network, both via transit routes through Belarus and Ukraine, and via pipelines sending gas directly into Europe (including the Nord Stream, Blue Stream, and TurkStream pipelines). Russia natural gas accounted for 45% of imports and almost 40% of European Union gas demand in 2021.[2]

In late 2019, Russia launched a major eastward gas export pipeline, the roughly 3,000 km-long Power of Siberia pipeline, in order to be able to send gas from far east fields directly to China. Russia is looking to develop the Power of Siberia 2 pipeline, with a capacity of 50 bcm/year, which would supply China from the West Siberian gas fields. No supply agreements and no final investment decision have yet been reached on the pipeline, which would further lessen Russia’s reliance on European customers for gas.[2]

Furthermore, Russia has been expanding its liquefied natural gas (LNG) capacity, in order to compete with growing LNG exports from the United States, Australia and Qatar. In 2021, Russia exported 40 bcm of LNG, making it the world’s 4th largest LNG exporter and accounting for approximately 8% of global LNG supply.[2]

In recent years, Russia has increasingly focused on the Arctic as a way to increase oil and gas production. The Arctic accounts for over 80% of Russia’s natural gas production and an estimated 20% of its crude production. While climate change threatens future investment in the region, it also presents Russia with the opportunity of increasing access to Arctic trade routes, allowing for further flexibility for seaborne deliveries of fossil fuels, particularly to Asia.[2]

Oil

[edit]Russia is a major player in global energy markets. It is one of the world’s top three crude oil producers, vying for the top spot with Saudi Arabia and the United States. In 2021, Russian crude and condensate output reached 10.5 million barrels per day (barrels per day), making up 14% of the world’s total supply. Russia has oil and gas production facilities throughout the country, but the bulk of its fields are concentrated in western and eastern Siberia. China is the largest importer of Russian crude (making up 20% of Russian exports),[2][14][15] but Russia exports a significant volume to buyers in Europe.[2]

While the Russian oil industry has seen a period of consolidation in recent years, several major players remain. Rosneft, which is state-owned, is the largest oil producer in Russia. It is followed by Lukoil, which is the largest privately owned oil company in the country. Gazprom Neft, Surgutneftegaz, Tatneft and Russneft also have significant production and refining assets.[2]

Russia has extensive crude export pipeline capacity, allowing it to ship large volumes of crude oil directly to Europe as well as Asia. The roughly 5,500 km Druzhba pipeline system, the world’s longest pipeline network, transports 750,000 bpd of crude directly to refiners in east and central Europe. At present, Russia supplies roughly 20% of total European refinery crude throughputs. In 2012, Russia launched the 4,740 km 1.6 million bpd Eastern Siberia—Pacific Ocean oil pipeline, which sends crude directly to Asian markets such as China and Japan. The pipeline was part of Russia’s general energy pivot to Asia, a strategy focused on shifting export dependence away from Europe, and taking advantage of growing Asian demand for crude. Russia also ships crude by tanker from the Northwest ports of Ust-Luga and Primorsk, as well as the Black Sea port of Novorossiysk, and Kozmino in the Far East. In addition, Russia also exports crude by rail.[2]

Russia has an estimated 6.9 million bpd of refining capacity, and produces a substantial amount of oil products, such as gasoline and diesel. Russian companies have spent the last decade investing heavily in refining capacity in order to take advantage of favorable government taxation, as well as growing global diesel demand. As a result, Russia has been able to shift the vast majority of its motor fuel production to meet EU standards.[2]

Russia’s energy strategy has prioritized self-sufficiency in gasoline, so it tends to export minimal volumes. However, Russian refiners produce roughly double the diesel needed to satisfy domestic demand, and typically export half their annual production, much of it to European markets. Europe remains a major market for Russian oil products. In 2021 Russia exported 750,000 bpd of diesel to Europe, meeting 10% of demand.[2]

Sources

[edit]![]() This article incorporates text from a free content work. Licensed under CC BY 4.0 (license statement/permission). Text taken from Frequently Asked Questions on Energy Security, International Energy Agency.

This article incorporates text from a free content work. Licensed under CC BY 4.0 (license statement/permission). Text taken from Frequently Asked Questions on Energy Security, International Energy Agency.

![]() This article incorporates text from a free content work. Licensed under CC BY 4.0 (license statement/permission). Text taken from Energy Fact Sheet: Why does Russian oil and gas matter?, International Energy Agency.

This article incorporates text from a free content work. Licensed under CC BY 4.0 (license statement/permission). Text taken from Energy Fact Sheet: Why does Russian oil and gas matter?, International Energy Agency.

References

[edit]- ^ "BP Statistical Review of World Energy 2021" (PDF). Retrieved 8 September 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l International Energy Agency (21 March 2022). "Energy Fact Sheet: Why does Russian oil and gas matter?". IEA. Retrieved 27 April 2022.

- ^ Sauer, Natalie (2019-09-24). "Russia formally joins Paris climate pact". www.euractiv.com. Retrieved 2021-11-08.

- ^ "Russia Energy Information | Enerdata". www.enerdata.net. Retrieved 2021-11-08.

- ^ Gustafson, Thane (20 November 2017). "The Future of Russia as an Energy Superpower". Harvard University Press. Retrieved 22 February 2021.

- ^ "Natural gas – proved reserves". The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 15 February 2022.

- ^ "Statistical Review of World Energy 69th edition" (PDF). bp.com. BP. 2020. p. 45. Retrieved 8 November 2020.

- ^ "Crude oil – proved reserves". The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 2 July 2021.

- ^ 2010 Survey of Energy Resources (PDF). World Energy Council. 2010. p. 102. ISBN 978-0-946121-02-1. Retrieved 8 November 2020.

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help) - ^ "Natural gas – exports". The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 2 July 2021.

- ^ "Natural gas – production". The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 2 July 2021.

- ^ "Crude oil – production". The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 2 July 2021.

- ^ "Crude oil – exports". The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 2 July 2021.

- ^ a b c International Energy Agency (24 February 2022). "Oil Market and Russian Supply". IEA. Retrieved 27 April 2022.

- ^ a b c d International Energy Agency (24 February 2022). "Gas Market and Russian Supply". IEA. Retrieved 27 April 2022.

- ^ International Energy Agency (13 April 2022). "Frequently Asked Questions on Energy Security". IEA. Retrieved 10 May 2022.

- ^ "Electricity – production". The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 2 July 2021.

- ^ Whiteman, Adrian; Rueda, Sonia; Akande, Dennis; Elhassan, Nazik; Escamilla, Gerardo; Arkhipova, Iana (March 2020). Renewable capacity statistics 2020 (PDF). Abu Dhabi: International Renewable Energy Agency. p. 3. ISBN 978-92-9260-239-0. Retrieved 8 November 2020.

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help) - ^ Long, Tony (27 June 2012). "June 27, 1954: World's First Nuclear Power Plant Opens". Wired. Retrieved 8 June 2021.

- ^ "Nuclear Power Today". world-nuclear.org. World Nuclear Association. October 2020. Retrieved 8 November 2020.

- ^ Whiteman, Adrian; Akande, Dennis; Elhassan, Nazik; Escamilla, Gerardo; Lebedys, Arvydas; Arkhipova, Lana (2021). Renewable Energy Capacity Statistics 2021 (PDF). Abu Dhabi: International Renewable Energy Agency. ISBN 978-92-9260-342-7. Retrieved 3 January 2022.