User:FiertlA/sandbox

| Mandakini River | |

|---|---|

Mandakini River along Chitrakoot, Satna | |

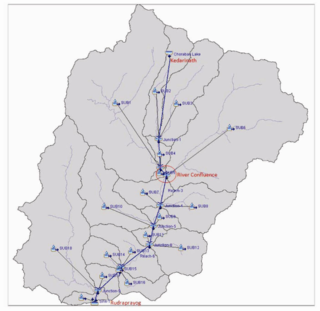

Hydrological setup of the Mandakini showing its course through Kedarnath | |

| Native name | मन्दाकिनी Error {{native name checker}}: parameter value is malformed (help) |

| Location | |

| Country | India |

| State | Uttarakhand |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Source | Chorabari Glacier |

| • location | Kedarnath Summit, Kedarnath, India |

| • coordinates | 30°44′50″N 79°05′20″E / 30.74722°N 79.08889°E |

| • elevation | 3,895 m (12,779 ft) |

| Mouth | Alaknanda River |

• location | Uttarakhand, India |

• coordinates | 30°08′N 78°36′E / 30.133°N 78.600°E |

• elevation | 3,880 m (12,730 ft) |

| Length | 81.3 km (50.5 mi)[n 1] |

| Basin size | 1,646 km2 (636 sq mi) |

| Discharge | |

| • average | 108.6 m3/s (3,840 cu ft/s) |

The Mandakini (Hindi: मन्दाकिनी) is a tributary of the Alaknanda river, located in the Indian state Uttarakhand.[1] The river runs for approximately 81kms (50.33mi) between the Rudraprayag and Sonprayag areas and emerges from the Chorabari Glacier.[2] The river merges with river Songanga at Sonprayag and flows past the Madhyamaheshwar at Ukhimath.[1] At the end of its course it drains into the Alaknada river which eventually flows into the Ganges.[1] The Mandakini is considered a sacred river within Uttarakhand as it runs along the Kedarnath temple and shrine of Madhyamaheshwar, an ancient Hindi temple.[3] For this reason, the Mandakini has been the location of great pilgrimages and religious tourism with treks passing significant sites of spirituality such as Tungnath and Deoria Tal.[4] The Mandakini area also sees millions of tourist annually with activities such as white-water rafting, hiking, and religious tours around the Winter Chardham being offered. In 2011 over 25 million tourists visited the river (comparatively, the State of Uttarakhand is about 10 million people).[3] Subsequently, however, the health of the river and surrounding landforms have slowly been degraded; giving rise to projects seeking the facilitation of environmental conservation such as the Kedarnath Wildlife Sanctuary.[5]

The Mandakini basin ranges in elevation from 3,800m (a.s.l.) to approximately 6,090m (a.s.l.) at the head of Chorabari Glacier.[1] Climates are generally cooler than the Indian mainland with maximum temperatures ranging from 30-36°C and a minimum of 0-8°C. Humidity is relatively high, especially in the Monsoon season (usually exceeding 70%).[6] The region houses very steep valleys and large slopes which commonly result in great sediment movement and landslides.[6] The Mandakini is also subject to heavy rainfall especially during Monsoon season. The annual rainfall within the surrounding region is 1000-2000mm which is elevated almost 170% in Monsoon seasons (late July-October).[7] This heavy rainfall is often responsible for rising water levels and intense flash floods.[2] In conjunction with the collapse of a segment of the dammed Chorabari Lake in 2013, an intense patch of heavy rainfall lead to the historical devastation of rural villages and death of thousands of locals, pilgrims and tourists. [8] These are known as the 2013 Kedarnath flash floods.

Etymology and names

[edit]In standard Hinduism, Mandākinī (मन्दाकिनी) signifies 'the river of the air or heaven.' As coined within the Vāyu Purāṇa, this name correlates to the Mandakini's high elevation and its course through significant spiritual locations.[9]

Within Shilpashastra (ancient Hindi texts referring to the arts and their standards within Indian culture), Mandākinī translates to 'slow' and refers to an illustration of Mandākinī-śruti - an ancient example of Indian religious iconography.[10] Her shapely beauty and flowing scarf are often seen in relation to the natural flow of the river. The items being held, particularly the vīṇā, are significant symbols within Hindi religion.[10]

In Purana and Itihasa (ancient Indian literature; commonly associated with legends and Indian lore), Mandākinī refers to the 'river which emerges from the holy mountain.'[11] This is referring to Kulaparvata in Bhārata, a region south to the South of Hemādri.[11]

In Marathi-English, Mandākinī translates to 'the milky way' or 'the galaxy.'[10]

In Sanskrit-English the Mandakini is called mandāka which roughly translates to 'the Ganges of Heaven.'[10]

Courses

[edit]With a total length of approximately 80kms (49.71mi) between regions Kedarnath and Rudraprayag, the Mandakini stretches past many significant locations of Uttarakhand. It also acts as a means of direction for passage through that particular area of the Garwhal Himalayas. [5] Due to great variety in weather and geographical conditions, such as the melting and reforming of the surrounding glaciers, discharge of the Mandakini fluctuates greatly throughout the year rather than remaining stagnant like many other, larger rivers (the Amazon, for example).[1] For these reasons, yearly discharge for the Mandakini has been split into categories; average monsoonal discharge, average daily discharge monsoonal discharge and daily discharge as well as charting the temperature and sediment levels of the water. [1] The highest discharge recorded (2018) was between 6 and 12m3/s observed from June to September with the average daily rainfall being 120-150mm.[1]

Source

[edit]

The Mandakini's single source is the Chorabari Glacier. The Chorabari is a medium-sized valley-type glacier which covers an area of approximately 6.6 sq. km within the Mandakini basin.[12] It is also one of the many glaciers nestled in the Himalayan region which many residents rely on for their water needs - situated between the Kedarnath summit to the north and the town of Kedarnath to the south.[13] In recent years (from data received between 1962 and 2014), however, exposure to higher temperatures and increased human intervention has seen a reduction in landmass of the Chorabari glacier (a loss of 1% of its frontal area and approximately 344m of its length).[12] As a result, the Mandakini river has seen steadily increasing water levels and potential for flash flooding. This also diminishes fresh water supplies for surrounding towns.[14]

History

[edit]Pilgrimage

[edit]The Madakini's rich religious significance dates back to its mention in the Srimad Bhagavad.[11] Its plethora of ancient Hindi temples, including the Jagdamba temple and Shiva temple also contribute to its holy significance. Over 10,000 pilgrims travel the main 16km Kedarnath trek along the Mandakini every year in order to reach the Kedarnath temple. The trek can be completed on foot or on a mule's back for a small fee.[4] Longer treks along the basin are also offered for locals and experienced tourists. These extend to the shrine of Tungnath and retrace the footsteps of important Hindi sages such as Swami Rama and Bengali Baba. People have also been known to bathe in the river during various religious events - such as baptisms.[15]

Role in the establishment of surrounding villages

[edit]

The Mandakini has been described as a "lifeline" for the town of Chitrakoot. Many small and large spring feed into the river at Sati Anusuiya - a holy and perennial reach of the river near the town. This water is used for drinking and domestic use (i.e washing clothes and bathing). Since the river often overflows, its banks are annually deposited new layers of silt - creating very fertile soil. Surrounding villages, Chitrakoot and Rambara, rely on the Mandakini for the cultivation of crops used in trade and consumption.[16] Many of these harvested plants are also used as natural medicines and aphrodisiacs, making Chitrakoot a hub for crop trade in the Mandakini area.[15] The river is known as Payasuni in the Chitrakoot region.[17]

2013 Flash Floods

[edit]

On June 16-17 2017, unprecedented rainfall and damage to dammed areas of the Chorabari glacier caused the Mandakini and its tributaries in the Garwhal Himalaya to flood and subsequently devastate surrounding villages.[4] The onslaught of water then caused large-scale landslides in the area. 137 seperate incidents of 'flash-flood induced debris' were charted within the Kedarnath valley.[8] Downstream settlements such as Kedarnath (2740m a.s.l.), Rambara (4410m a.s.l) and Gaurikund (1990m a.s.l.) were the most heavily impacted due to an accumulated debris build-up from damaged villages upstream; creating a 'snowball effect' of devastation.[8] During the floods, the main channel of the river increased approximately 406% with about 50% (7km) of the single pedestrian route (14km) between major villages Gaurikund and Kedarnath being completely washed away. As a result, rescue operations for tourists and locals was completely impeded and evacuation was unable to be effectively completed. Over 1000 deaths of tourists, pilgrims and locals were recorded in the following months.[4] Approximately 120 buildings in total; 90 of these surrounding the Kedarnath shrine and within Rambara (small village downstream). While numerous homes and farms were destroyed in the floods, the majority of shrines and the Kedarnath temple were miraculously left intact. Locals were even seen trekking to the temple and praying only days after the disaster.[4] Pilgrims and locals reported 'black clouds' and 'black water' taking over the land and the skies on the day of the flooding.[4]

It is theorised that increased construction of hydropower projects, exponential growth in tourism and a steady increase in emission of greenhouse gases (GHGs) all contributed heavily to the disaster. Thus, modern day scientists have made efforts to recuperate areas of the land through methods such as conservation plans, wildlife sanctuaries and the strategic placement of concrete blocks to restore the original and favoured course of the river.[19][8]

Biodiversity

[edit]Due to its great length and varying altitude, the Mandakini houses vast biodiversity.

The soil is dark brown to brown at the surface and brown to yellowish in the subsoil.

The floristic composition of the forest area of the Mandakini consists of Rhododendron, Quercus leucotrichophora (Banj), Quercus floribunda (Moru), Quercus semecarpifolia (Kharsu), Buxus wallichiana (papri), Acer spicatum, (kaijal), Betula alnoides (katbhuj), Anyar (Lyonia), Alnus nepalensis (Utis).[20]

Many smaller, medicinal herbs are found along the shallower banks of the river. These are as followed: Abies pindrow, Aconitum, Balfourii, Adhatoda zeylanica, Aesculus indica, Angelica glauca, Artemisia roxburghiana, Boehmeria rugulosa, Boerhavia diffusa, Brugmansia suaveolens, Centella asiatica, Foeniculum vulgare, Geranium nepalense, Geranium wallichiana, Berginia ciliata, Bidens pilosa, Berberis aristata, Berberis lycium, Oberonia falconeri, Ocimum tenuiflorum, Ajuga lobata, Polygonatum multiflorum, Polygonatum verticillatum, Rosa sericea, Satyrium nepalens, Sida rhombifolia, Stephania glabra, Swertia chirayita, Taxus baccata, Vanda cristata and Vitex negundo.[17]

Aquatic floral biodiversity of the Mandakini also varies greatly and is therefore categorised into categories. These are as followed: (1) Fixed floating plants (in contact with soil, water and air), (2) Free floating plants (in contact with air and water only), (3) Fixed submerged plants (vegetative plants whose flowers are raised slightly above the surface of the water), (4) Free submerged plants (in contact only with water and are rootless), (5) Emergent Amphibious plants (roots and leaves are submerged under water), (6) Marshy Amphibious plants (occur in soft wet mud or forming reed swamp vegetation along banks), (7) Wetland plants (along or slightly away from the banks of the river).[17] Studies reveal there are currently 119 species of aquatic plant life in the Mandakini surrounding Chitrakoot. 63% of these are classified as dicots, 31% as monocots and a further 6% as pteridophytes.[17][20]

Environmental Impacts

[edit]Geography

[edit]

Because of the altitudinal variation of the Mandakini, climate conditions vary throughout the region (altitude ranging from 210 to 7187m a.s.l).[20] A general increase in temperatures, which scientists attribute to climate change, has however been recorded in the area. As a result, soil erosion has increased and soil productivity has decreased. This has caused more frequent large-scale landslides and the inability for new crops to grow and be harvested. Increased levels of rainfall have also been attributed to climate change, with scientists predicting larger numbers of soil loss occurring over coming years.[6] Studies show that moraine-dammed lakes, which are also attributed to the melting of snowcaps and increased rainfall, are also giving rise to lake outburts and subsequent flash flooding.[20]

The Mandakini region is seismically and ecologically very fragile due to its position along a collision zone. Well-exposed crystalline rock groups in the Higher Himalayas and surrounding Kedarnath form the oldest crystalline base in the Himalayan region. This rock is highly susceptible to displacement and is also one of the biggest triggering agents to the many landslides in the region.[20]

Constant flooding, particularly following the flash floods of 2013, has seen the decline in forest density along the Mandakini. Data received from scientists indicate that the area of forest pastures diminished from 1240.98 ha to 1207.80 ha between 2012 and 2013.[5] Hence, soil fertility and diversity in flora and fauna have been in steady decline since 2013.[17] The fragmentation of forest area has also resulted in a loss in land for usage in husbandry, agriculture, and tourism.

Human Intervention

[edit]The Mandakini has become a prime location for investigating the impact of waste dumping and tourism on the quality of water.[3] Due to its cultural and religious significance, the Mandakini and neighbouring villages attracts thousands of tourists and pilgrims each year.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g Rawat, Anjani; Gulati, Gunjan; Maithani, Rajat; Sathyakumar, S.; Uniyal, V. P. (2019-12-20). "Bioassessment of Mandakini River with the help of aquatic macroinvertebrates in the vicinity of Kedarnath Wildlife Sanctuary". Applied Water Science. 10 (1): 36. doi:10.1007/s13201-019-1115-5. ISSN 2190-5495.

- ^ a b "Mandakini River - About Mandakini River of Uttarakhand- Kedarnath flash flood". eUttaranchal. Retrieved 2020-10-06.

- ^ a b c Kala, Chandra Prakash (2014-06-01). "Deluge, disaster and development in Uttarakhand Himalayan region of India: Challenges and lessons for disaster management". International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction. 8: 143–152. doi:10.1016/j.ijdrr.2014.03.002. ISSN 2212-4209.

- ^ a b c d e f Bahl & Kapur, R&R (|date=18 June 2018). "Kedarnath Flash Floods: Did Anything Change After Five Years?". Youtube. Retrieved |access-date=3 October 2020.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|access-date=and|date=(help)CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ a b c Kansal, Mitthan Lal; Shukla, Sandeep; Tyagi, Aditya (2014-05-30). "Probable Role of Anthropogenic Activities in 2013 Flood Disaster in Uttarakhand, India": 924–937. doi:10.1061/9780784413548.095.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ a b c Khare, Mondal, Khundu & Mishra (2017). "Climate change impact on soil erosion in the mandakini river basin, north india". Applied Water Science. 7(5): 2373–2383 – via ProQeust.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Khare, Deepak; Mondal, Arun; Kundu, Sananda; Mishra, Prabhash Kumar (2017-09). "Climate change impact on soil erosion in the Mandakini River Basin, North India". Applied Water Science. 7 (5): 2373–2383. doi:10.1007/s13201-016-0419-y. ISSN 2190-5487.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ a b c d Bhambri, Rakesh; Mehta, Manish; Dobhal, D. P.; Gupta, Anil Kumar; Pratap, Bhanu; Kesarwani, Kapil; Verma, Akshaya (2016-02-01). "Devastation in the Kedarnath (Mandakini) Valley, Garhwal Himalaya, during 16–17 June 2013: a remote sensing and ground-based assessment". Natural Hazards. 80 (3): 1801–1822. doi:10.1007/s11069-015-2033-y. ISSN 1573-0840.

- ^ Deoras, V. R. (1958). "THE RIVERS AND MOUNTAINS OF MAHĀRĀSHṬRA". Proceedings of the Indian History Congress. 21: 202–209. ISSN 2249-1937.

- ^ a b c d www.wisdomlib.org (2009-04-12). "Mandakini, Mandākinī: 19 definitions". www.wisdomlib.org. Retrieved 2020-10-08.

- ^ a b c www.wisdomlib.org (2019-02-17). "Varahapurana, Varāhapurāṇa, Varaha-purana, Vārāhapurāṇa: 6 definitions". www.wisdomlib.org. Retrieved 2020-10-08.

- ^ a b Karakoti, Indira; Kesarwani, Kapil; Mehta, Manish; Dobhal, D. P. (2017-04-01). "Modelling of Meteorological Parameters for the Chorabari Glacier Valley, Central Himalaya, India". Current Science. 112 (07): 1553. doi:10.18520/cs/v112/i07/1553-1560. ISSN 0011-3891.

- ^ "Chorabari Glacier, India". earthobservatory.nasa.gov. 2008-03-14. Retrieved 2020-10-25.

- ^ Kozma, Eszter; Jayasekara, P. Suresh; Squarcialupi, Lucia; Paoletta, Silvia; Moro, Stefano; Federico, Stephanie; Spalluto, Giampiero; Jacobson, Kenneth A. (2013-01-01). "Fluorescent ligands for adenosine receptors". Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry Letters. 23 (1): 26–36. doi:10.1016/j.bmcl.2012.10.112. ISSN 1464-3405. PMC 3557833. PMID 23200243.

- ^ a b Rani, Gupta & Shrivastava, R., B.K., & K.B.L (2004). "Studies on enviro-ecological status of Mandakini river in Chitrakoot". Pollution Research. 23(4): 677–679 – via Institutional Repository.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Kwartalnik Pedagogiczny. University of Warsaw.

- ^ a b c d e Sikarwar, R.L.S (2013). Aquatic Biodiversity of the River Mandakini of Chitrakoot. Uttar Pradesh State Biodiversity Board. pp. 70–74.

- ^ Clarence, Kathy (2013, June 19th). "Mandakini River Damaging Houses in the Kedarnath Valley". Floodlist. Retrieved 9 October 2020.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help)CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Kumar, Yogesh. "Mandakini river's original course by Kedarnath restored". The Economic Times. Retrieved 2020-10-09.

- ^ a b c d e Uttarakhand Space Application Centre, Dehradun, Uttarakhand, India; Rawat, Neelam; Thapliyal, Asha; Purohit, Saurabh; Singh Negi, Govind; Dangwal, Sourabh; Rawat, Santosh; Aswal, Ashok; M.M., Kimothi; Uttarakhand Space Application Centre, Dehradun, Uttarakhand, India (2016-04-05). "Vegetation Loss and Ecosystem Disturbances on Kedargad Mandakini Subwatershed in Rudraprayag District of Uttarakhand due to Torrential Rainfall during June 2013". International Journal of Advanced Remote Sensing and GIS. 5 (1): 1622–1669. doi:10.23953/cloud.ijarsg.50.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)