User:Hans-Jürgen Hübner/sandbox

History of the Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in First Nation

The history of the Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in First Nation, a First Nation in the canadian Yukon, spans over ten milennia. The members of this indian group live in the area of Dawson, that is why they formerly were called Dawson Indian Band or, with a focus on their language Han, although this language was also used by small, closely related groups in eastern Alaska. The current name was officially adopted by the Nation in 1995.

The indians accomodated themeselves to the climate of the Canadian Northwest withiin the frame of a half-nomadic lifestyle, which relied on winter-villages and Vorratswirtschaft as well as Wanderzyklen. These circles depended on hunting and gathering grounds. Fish, especially salmon, and caribou-hunting were fundamental for feeding, clothing and making tools. Parts of these tools, like Obsidian, but also of the Schmucks, like certain kinds of shells or copper, reached the tribe via a network of far reaching contacts of exchange, gift and trade, which stretched out to Alaska, northern British Columbias, to [[Vancouver Island and the Northwest-Territories. Bow and Arrow replace the Atlatl from about A. D. 600 on.

European traders, who came into contact with this extensive system of paths and goods, were integrated into this network for a couple of decades, although the developing world-trade, within which the worldpowers Russia and Britain were strong promoters and intermediaries, dominated by far. In 1847 some Han came into direct contact with british traders for the first time. in 1874 they asked an american trading company to erect a Fort within their territory.

In the beginning the british Hudson's Bay Company was in competition with russian fur traders, and – after the Alaska Purchase of 1867 – with american traders, especially of the Alaska Commercial Company.

But it was deseases that enforced a much more rapid and radical change than did the trade with the foreigners, especially small-pox, measles and tuberculosis – a phenomenon, that hit most indians. In additon, the first men, looking for gold, reached the Yukon, which further changed the traditional way of living.

But it was the Klondike Gold Rush that brought thousands of people to the region beginning in 1896. This made the Han a small minority of some hundreds of people, compared to the hundred thousand invaders.. In addition urban influences and the transfer to Moosehide, a few kilometres away from Dawson, where the tribe lived between 1897 and about 1960, was a great challenge. The leader in these difficult times was Chief Isaac, who died in 1932.[1] He resisted the destruction of the traditional ways, opposed against the destruction of the natural resources, especially against overhunting the caribou herds and the destruction of the forests.

A tribal council developed in Moosehide and the traditonal chiefdoom was replaced by elected leaders. Only few possibilities existed in Yukon’s mining industries, in addition many lost their jobs in the Great Depression. So many Tr’ondek continued their tradtional ways, but during the 1950s the fur-market collapsed. Most indian groups were rather isolated as the population declined and most white people left the Territory after the gold-rush. In addition a strong policy of segregation, but also neglect made the isolation even stronger.

The Canadian First Nations gained the right to participate in electiions (1960) and to improve their control over their lands. In 1998 the Tr'ondek Hwech'in, who carried this name officially since 1995, signed a treaty with the governments of Canada and the Yukon, which brought back control over their traditional territory, although with very different rights within its parts. In the same year a constition brought judicial rights to the tribe. Language and culture are promoted, and better known to the external public – after the Canadian government had tried to extinguish all indian cultures. The representations of the culture has become an important part of regional tourism.

Early History[edit]

The Early History of the Yukon can only be traced by archaeological findings[2], except oral traditions, which are difficult to interprete. The most important site is Tr’ochëk, an island, which today is on the List of National Historic Sites of Canada in Yukon immediatly opposite of Dawson.

Until the end of the last ice-age, so called Beringia was a vast Tundra, which stayed ice-free for lack of precipitations, while Eastern Siberia and Canada eastwards of the Yukon River was lying under huge glaciers.

Earliest fundament of living was – besides the Megafauna of the post-glacial epoch, of which we have no traces in Tr’ondek territory - Caribou herds, especially Porcupine and Forty Mile Herd, which twice a year crossed the area of Dawson.[3] Also of importance were moose, sheep, marmots and squirrels as well as birds and fishes, most of all salmon, caught in the Yukon and the Klondike Rivers. Chinook and later in the year Chum came to Laich up the Yukon and ist Nebenflüsse and offered opportunities from the end of june. Very early the prey was dried on racks, and prepared for the cold winter.

First traces of human presence (11,000 years ago)[edit]

Along the Yukon a highly mobile hunter society developed. The oldest sites are the three Bluefish-caves which bared artefacts about 12,000 years old. The Early Arctic Culture spread southwards, probably along the River. Microblades and bifaces are typical for this culture.

In Moosehide and around Dawson the traces of human occupation are about 8,000 years old. The oldest finding is a [[Abschlag (Archäologie)|Steinabschläge, found about 50 cm below the surface. The oldest trace is a caribou antler, which is about 11,000 years old. It was found on the Hunker Creek, a tributary of the Klondike.[4] In dieser frühen Phase war die Region noch weitgehend unbewaldet.

Microblades, 5000 bis 3000 B.C.[edit]

Ca. 7,000 years ago the massive tools were substituted by composite-tools, which consisted of bones, antlers and very small microblades. The oldest traces in Moosehide are between 3,600 and 4,500 years old.[5] There was also found [[Obsidian], a kind of volcanic glass, that indicates a wide range of trade, because it does not occur in the region naturally, but only in southwestern Yukon and northern British Columbias, e.g. Mount Edziza. In addition lanceolate projectile points were excavated, pieces of mammal bones, and a stone, which was probably used as a net sinker.

Side-notched points[edit]

5,000 to 4,500 years ago, the tool-making technique changed. The microblades disappeared and were replaced by side-notched pojectile points, a wide variety of scrapers. As a hunting weapon the Atlatl was in use, which could reach much farther and überbot die Durchlagskraft of the spears. The salmons, which returned year by year, were one of the reasons, why the human groups were soon used to yearly rounds between the hunting and fishing grounds. This period is called |Northern Archaic tradition.

Bow and arrow, copper[edit]

Arrows and bows are foudn as early as about 600 A. D. , probably adopted from the Inuits. This new weapon verdrängtte the Atlatl by and by. Partially tools made of stones were not the only technological improvements, but there also occured metallugical techniques. They were based on copper trade, a metal that came from the southwest, i. e. the Copper and the [[White River (Yukon)|White River]s.

Volcanic eruptions and the late „prehistoric“ period (ca. 100–1750)[edit]

In the White River area, close to the border between Alaska and Yukon, two of the strongest volcanic eruptions took place at about A. D. 100 and 800.[6] Close to the peak of Mount Churchill (4766 m) they left behind a Caldera of 4,2 x 2,7 km. 50 km³ of ashes probably destroyed every trace of linving in an area of about 340,000 km² in southeastern Alaskas and southern Yukon. The uninhabited areas have isolated the northern parts of the Yukon-Territory, and with that the Han’s ancestors, from the south.

After these catastrophes the so called Late Prehistoric, a time of repopulation followed.

Copper was used for different tools like awls and projectile points, but was also used for adornments. Dentalia and Obsidian reached the Tr'ondek Hwech'in. They in return offered birch bark, used for baskets, red ochre for dyeing and dried salmon. These transactions, often described as trade or barter, were much rather a kind of gift exchange (Gabentausch) This kind of exchange allowed the participants to exhibit their respect againsts certain persons or groups and demonstrated the social status of giver and taker. Meetings and celebrations, like the Potlatch, offered opportunities to „trade“ within a ritualized frame. This intense trade was based on a vast network of paths and routes along the many rivers and lakes. Although many sites where gold could be found, this material did not yet play the significant role that it took over in later times under completely different conditions.

Before the first Europeans[edit]

At about 1800 six language groups existed within the later Yukon Territory, five of which belonged to the [[Athabaskan]s, one to the Tlingit. Culturally closely related groups met one another regularly, especially when it came to fishing during spring and summer. These larger groups converted to family-based groups, as soon as the means of living became less abundant at the beginning of the autumn. The winter was spent in winter-villages. Most Indians lived in valley and close to the lakes, the uplands were visited for hunting only. But not alle the tribes were specialists in all hunting, trapping and fishing techniques. The Han groups were excellent constructors of fish nets and traps.

The ability of the region for regeneration worked very slowly, the resources were not scarce but scattered, and this forced the people take care of their natural resources. At the same time people developed a seasonal migration between these spots, a sophisticated knowledge which altogether made a rather safe and comfortable life possible. This stood in harsh contrast to the many victims among the white people, their aversity to live in the north, an attitude hardly understandable for the Tr'ondek Hwech'in.

Under these circumstances a leading social group could hardly emerge, and even if, its continuity depended heavily on success and ability of single personalities. Formally, women were not part of the ranking ordre, but they were brilliant teachers, story-tellers and gatherers of strong influence.

Shamans, often called medicine men or sorcerers by Europeans, who excelled in knowledge of nature and ist powers or ghosts, gained great influence, and they were often healers. They were also responsible for making contact with spiritual powers, they helped the hunters to find their prey, and they tried to influence the weather.

Regional and local groups[edit]

As part of the larger groups there existed regional bands, like the Han, local bands and task groups, groups which came together to solve a certain task. Regional groups came together only, when gatherings like potlatches were announced. An other prerequisite was a spot where natural resources were sufficient for larger groups. The regional groups were closely tied by kinship and common language as well as a traditional territory.

The regional group of the Tr'ondek were the Han. The local band, in this case the Tr'ondek Hwech'in, had a traditional territory within the territory of the regional group. There they had certain rights of use. Each of these groups had a winter village, a traditional migration circle, which brought them to the important spots for hunting and gathering. The traditional territories overlapped, depending on season, rights of exploitation and even single persons making use of their rights. Sometimes existing local groups were split, other groups came together, sometimes men connected by friendship came together for hunting or fishiing.

The regional group of the Han consisted of local groups, which were called David's und Charley's band in today’s Alaska and the group on the Klondike. Only the last one is called Tr'ondek Hwech'in. It is unclear, if a fourth band existed at Nuklako (Jutl’à’ K’ät), or if it was part of the Klondike group.

Charley's band was the northern moste. It settled at the mouth of the Kandik River into the; this riverlet ist known as Charley Creek not to be mixed up with Charley River. On the opposite side, at Biederman Camp, there was another village, possible a third one ten miles down the Yukon on Charley River. Independence, a short-living gold-rush village arouse. Possibly between 1900 and 1910 the people from Charley River migrated to Fort Yukon. Charley Village was distroyed in 1914 by an inundation. . Ist chief brought many people to Eagle Village. It is unclear, if there were two chiefs with the same name. One of them was mentioned in 1871 by the anglican missionary Robert McDonald who was received gently by the chief. In 1910 25 people lived in Charley Creek Indian Village 25 of which 17 were Han, the other ones belonged to Gwich'in-tribes. In 1911 there were only 10 to 12, in 1912 even 7. Most of the lost people were probably victims of flu epidemic. An inundation destroyed the village in 1914, its few inhabitants went to Circle City.

David's band, which in 1890 consisted of 65 to 70 people, regularly wintered on Mission Creek and on the Seventymile River. Their hunting territory streteched to Comet Creek and Eureka Creek as well as to American Creek. Most of this group died during the 1880s from small-pox, the surviviors went to Fortymile. One of their camps was Eagle, where six houses stood. The trading spot below the village was Belle Isle, but it was surrendered at htis time. Two and a half mile downriver from Eagle their was another village with eight houses, which was also surrendered. Chief David died in 1903 or earlier, when a potlatch was celebrated in his honor. His son Peter followed him as chief.

The biggest local band was the one on the Klondike, but their hunters never went farther then All Gold Creek, a tributary of the Flat Creek, about 50 km north of Dawson, because they feared the Mahoney. With them they were in quarrel since a long time ago.[7] The Tr'ondek people went downriver with their canoes before wintertime. They reached Coal Creek or Tatondiak River, or Nation River. They spent the winters in the Ogilvie Mountains. Before winter’s end they went to the Klondike, built birch bark canoes [8] and caught salmon on the mouth of the river.

Trade, Exchange, Gifts[edit]

The Tr'ondek were part of an extensive trade network. Within this larger frame the Chilkat, part of the Tlingit brought goods from the coast across two difficult passes into the hinterland. This was the way seal oil, Eulachon (an oil similar to butter), dentalia, boxes made of cedar wood, healing plants, as well as european goods like knives, pans and beads, which were of upmost importance for the representative desires of the leading social strata, were brought in large quantities to the Tutchone of southern Yukon. They offered furs, the leather of caribous or copper, in addition goat hair, sinews and colors.[9] The Han groups that lived north of them, changed goods with their furs, red ochre – a colour made of birch bark and salmon. They again traded the goods with the Gwichin in the north, indian groups who were in contact with the Inuit peoples. These trade networks were supported by kinship, which, for example, brought Tlingit cultural influence far into the Yukon.

Trade with Europeans, epidemics[edit]

Southern as well as northern groups came into contact with Europeans at the ende of the eighteenth century. Alexander Mackenzie mit some Gwich'ins and in 1806 Fort Good Hope was erecrted. Beads were quickly adopted as means of change and of measurement. Against the resistance of the neighboring Iunits, of whom 500 attacked the fort, the Gwich’in defended their trade monopoly between 1826 and 1850. setzten sich in der Region als Tauschgut und als Wertmaßstab schnell durch.[10]

On the west coast there was much more antagonism and the aboriginal people resisted vigorously. In 1741 the first Russians appeard in Alaska. In 1763 Unangan killed about 200 inhabitants of Unalaska, Umnak and Unimak Island, Russians in revenge killed about 200 people. In 1784 there were battles on Kodiak Island between Russians and Tlingits, 1804 the Batte of Sitka; until 1819 the Tlingits left the island. Despite their military superiority the Russians were not able to spread their fur trade monopoly against the resistance of the Tlingits. The Britains appeared at Wrangell and pachteten the southeastern mainland from the Russians. The Spaniards who sailed northwards and tried to control the northern Pacific gave up their .... when they signed the Adams Onís treaty in 1819. Twenty years later the first russian trading post was built on the lower Yukon. From this fort named Nulato Lavrentiy Zagoskin started his expedition up the Yukon in 1842.

For the tribes outside the areas of influence of russian or british trade companies, the appearance of the Europeans did not change the trade systems very much. They were already used to most of the products.

In strong contradiction a much stronger factor were diseases, especially the ones against which natives had no immunological response. The loss of human beings is hard to estimate. James Mooney[11], estimated 4,000 Indians in the Yukon Valleys, following Alfred Kroeber there might have been 4,700. But these estimates are very insecure. In the 1960s their numbers rose to 7,000 or even 9,000. In 1895 there were probably onloy 2.600 alive, keeping in mind that even this number is probably only a good guess.

We do not know if the population was diminished as heavily as in the years after 1775, or as it was the case in Sitka before 1787. [12] What we know is that from 1835 to 1839 small pox devastated Alaska and the area on the Lynn Canal. In 1847 missionary Alexander H. Murray wrote about high mortality rates, especially amongst the women; similarly Robert Campbell in 1851. Murray estimates, that 230 Han were trading around Fort Yukon - they were the largest group. If this relatively high number is correct, we have to face the fact that this group alone consisted of at least 800 human beings.[13] In 1865 men of the Hudson's Bay Company brought a Scharlachepidemie to the Yukon River. James McDougall believed that half of the people around Fort Youcon died.

The infection rate was accelerated by two facts: The infected people had enough time – the Incubation period in the case of small pox was one to two and a half weeks – to flee into the shelter of their relatives, or they assumed sorcerers from another tribe to be guilty of the disease and started revenge wars. Both reactions lead to numerous new infections, against which no shaman had any means. In 1865 the HBC once again mourned that women were much heavier hit by the disease and that the best hunters were lost. Lots of other spots, where unknnown diseases ravaged, the loss of up to two thirds of the population were not unusual. In addition early death prevented the people from weitergeben their cultural elements and capabilities, the leading groups came under heavy pressure of legitimation, and as a whole this endangered their trust in their spiritual world.[14] When british and Han people met for the first time, the culture of the lattter ones had already changed a lot, their number had decreased to an unknown degree.

Trade monopolies: Britains, Russians, Indians[edit]

In 1839/42 russian traders came to the lower Yukon, british to the Mackenzie River in 1806. Intermediaries had brought european trade goods into the region already for decades. The Tliingit were dominant iin this trade in the west, the Gwich'in in the north east.

Falling prices for beaver furs forced the british traders to find more rare and expensive furs, so they went much farther northwards. John Bell opened a post on the Peel River, later called Fort McPherson. But the Gwich’in living there wanted to make use of their monopoly as intermediaries and to prevent the British from going farther to the west. So they exaggerated when it came to transportation obstacles, even lead some traders the wrong way or left them on their own. Bell looked for other indian path finders in 1845, who were more successful. As a consequence the Gwich'in had to give up their resistance after about five years. In 1846 the small trading post Lapierre's House on the western slope of the Richardson Mountains was built, in 1847 Fort Youcon about 5 km up the mouth of the Porcupine River. In exchange with provisions and european goods the indians of that area were the profiteers of the new forts and they could enjoy the new Ansehen.

During this time the HBC tried ist luck in the south. Robert Campbell built a trading post in 1838/40 on the Dease Lake others followed on Frances Lake and on the upper Pelly River. But the more he approached the Yukon the more he felt the trading system of the Chilkat-Tlingit, so that in 1843 his men, angeblich for fear of the „savages“, returned.

Members of the Southern Tutchone even talked about cannibalism.[15] Despite that Campbell erected a post at the confluence of Pelly and Yukon in 1848, but in the following year 30 Tlingit stopped his traders. He was not able to make sufficient profits during the following five years, but he came into contact with the Han, because he came through their territory when he went down the Yukon to Fort Youcon. On the 19th of August 1852[16] Chilkats pillaged and destroyed the post that was laying on an island in the Pelly River. Campbell knew too well that knowledge of the area, of customs and languages brought decisive advantages to the Chilkats. In additon the HBC relied on the Liard River which was difficult to canoe. In addition the price structures depended on the interests of the traders in the Mackenzie area in the east. While the ‚Chilkat depended much rather on the prices of the Pacific. Two trading circles met in the Yukon, the one in the west was directed to the Pacific and especially to China, while the eastern one depended on Europe. The HBC was forced to give up the southern Yukon in advantage of Fort Youkon in today’s Alaska.

Another missunderstanding was fundamental. The HBC had always believed in ist strategy to start making contact the trading chiefs. But the British did not realize that, although indians elected a trading chief, they did not have to obey him, and so they brought their furs whereever better prices were offered. In additon HBC traders were no longer allowed to give goods on credit – another missunderstanding, The Indians did not thiink of trading only as a way to exchange goods, but also as a kind of gift giving. Here, honour and prestige were much more important criteria. In addition there was often a gap in time between giving and compensating. Consequently the Indians went to Fort Youcon where they could buy on credit. They reached their goal by making use of the competition between the Russian American Company and the HBC. When a russian agent appeard on the upper Yukon, Strachan Jones went several hundred miles downriver, to persuade the people there to come to Fort Youcon.

In the years following those indians lost their monopolies, but they on their side made use of the competition between Youcon and Mackenzie district by going here or there depending on the conditions – an advantage of their nomadic lifestyle. They also verweigerten to deliver meat for the posts which heavily depended on their hunting success. A monopoly was impossible to reach. When the Americans found out that Fort Youcon was on their territory after the Alaska Purchase of 1867, the British had to leave their Fort in 1869. The trading networks changed dramatically.

First direct contacts between Han and Europeans[edit]

The Tr'ondek were relatively flexible but prevented other tribes like the Copper Indians from the White River district from comiing to their trading spots, e. g. Forty Mile. Similarly the Tlingit kept the Copper Indians off Haines. That was the reason why the first european visitors, members of the North West Mounted Police, in 1873 had the impression that these indians were comparatively backwarded, had old guns etc. The situation was quite similar until the gold-rush with the Kaska in the south-east and with the eastern Tutchone.

When the first Europeans entered the Tr'ondek territory, their chief was Gäh St’ät or „Rabbit skin hat“ , whom they called „Catsah“.[17] They also realized that, besides traditional goods like birch bark, red ochre, fur or salmon, european goods like tea, tobacco glas-beads and kettles were widespread.

The first known contact between Europeans and Han took place on April 5, 1847. The HBC trader Alexander Hunter Murray writes about the meeting at LaPierre's House on the upper Porcupine River. Murrray called them „Gens de fou“. Their leader was a young Chief, who had brought 20 Marderfelle, which he wanted to offer for a gun. The group had also half-dried goose tongues, caribou skins and furs. Three of them had already seen white people, probably Russians, with whom they had presumably traded at Nulato. In sharp contrast to the „Rat Indians“ - the Gwich'ins who hunted Bisamratten - they were looking forward to the establishment of Fort Yukon, which was much closer to their territory.

In early August 1847 a larger group visited the fort for the first time. But Murray had been warned by some Gwich’ins that the Han were angry at the British traders, because they believed that the death of one of their chiefs had something to do with the arrical of the strangers. When the 25 canoes arrived at the fort, they came in complete silence, without the usual singing and talking of the other athabascan people. For Murray the Han looked very „wild“, as they wore long hair and their shirts were geschmückt with beads and Messing. They brought pipes made of zinc and Bleck, which they had traded from Russinas. They themselves had only very few things, just some bear furs, meat and a hundred geese, which they had hunted on their way. On the second day some of them threatened they were prepared to destroy the fort if treated badly, like they had done with the Russians – for which we have no trace. What they desired most was goods on credt, what Murray refused to do.

Until 1852 at least seven times employees of the HBC crossed the Han’s territory, among them the men, which paddled downriver to Fort Youcon, and also interpreter Antoine Hoole, who went down the river in 1851.[18]

Alaska Purchase of 1867, new competitors in the fur trade, trading posts[edit]

Despite of these difficulties Fort Yukon remained the main trading post for the Han people until 1869. The Alaska Purchase made the western branch of the Han Alaskans i. e. Americans, the eastern branch Canadians. The later chief Isaac came from Alaska. He belongred to the Wolf Clan and was born c. 1859. He married the daughter of a chief named Eliza Harper, member of the Crow Clan, the other Clan of the Han. Interemaariage between the clans wa allowed only, never within the clans. The coule has probably lead about 2200 people.

Already in 1873 Moses Mercier, who had to leave Fort Youcon, had founded a small trading post namend Belle Isle on the left bank of the Yukon River, close to our day’s Eagle in the territory of the Han people.[19] At the end of august 1874 Leroy Napoleon McQuesten, better known as Jack McQuesten, founded a second trading post namend Fort Reliance, about 10 km downriver of the mouth of the Klondike River, which he knew as „Trundeck River“. Together with Frank Barnfield[20] he built a hut. He was helped bei indian men, who felled the trees and carried the Stämme, others hunted for them. McQuesten was the onoly white man who stayed for a longer period, for 12 years to be more precise. The small Fort measured only 30 to 20 feet[21] Han, Upper Tanana and Northern Tutchone met there. He called hhis neigbors „Klondike Han“. For a couple of years he and his partners tradied and bought furs for the Alaska Commercial Company, which McQuesten worked for. He also manoeuvered the Yukon, the first steamer, a stern-wheeler, on the Yukon River.

The Alaska Commercial Company had bought ist trading monopoly from its russian competitors in 1867 for 350.000 dollars, Till 1874 it had a veritable monopoly on the lower Yukon but private competitors were still on the spot. Many indian groups made advantage of this competition. The British were now much easier prepared to sell on credit now at Rampart House. They needed even more pathfinders, huntrs, trappers, fishermen and Dolmetscher, their treaties lasted now for six instead of three months, but they could not go downriver 300 km to Nuklukayet as they used to do. The american competitors were much more aggressive und offered better prices, went to more remote areas and visited groups never visited before. They even sold british goods and made the indians relatively free partners of their business. In addition they brought a steamer of 17 m of length onto the Yukon, accelerating and increasing the transportation.

Chief Catsah (Gah ts'at) asked the HBC for a Fort in 1874, but this Fort Reliance had to be given up in. 1877 or 1878, as there occurred some quarrels – as far as we can guess froom american sources – because someone stole tobacco. In addition some women had entered the left Fort and tried some poisoned Fett. A sixteen year old, blind girl died.. McQuesten and the chief negioted successfully for compensations, the mother of the dead girl accepted a dog, McQuesten re-opened the post in 1878 and the Han offered some compensation for the tobacco.

The Western Fur and Trading Company built a competitive fort 130 km downriver near David's Village in the area of today’s Eagle. Moses Mercier had to give up this unprofitable post in 1880. In 1882 he, now for the [[Alaska Commercial Company, founded Belle Isle in the same area As a quick reaction his former employer re-opened the former post and the two companies competed sharply. This advantageous situation, at least for the Han, ended in 1883 already, when the Alaska Commercial Company bought ist rival. Now the new-borne monopolist wanted higher prices for ist goods and offered lower ones for the Han goods – and offered credit much less generously.

Steamers like the Yukon of the ACC, or from 1879 25 m long St Michael of the Western Trading and Fur Company, increased the transportation capacities heavily. In 1887 the New Racket, built by a group of goldminers appeard, which the ACC could buy. Bulky goods, flour and - what the HBC always had denied - Repetiergewehre und Segeltuch for tents came into the area, as well as exotic goods like chinese tea cups. The Han’s position of ntermediaries became stronger this way. In 1889 a gigantic boat of more than 40 m of lenght, the Arctic , transported even more goods and passengers - after the beginning of the gold-rushhinzu, even 70 m were reached.[22]

As a further factor whale hunters came to Herschel Island, in the 1880s, an island far iin the north on the coast of the Beaufortsee. They brought Winchester-Repetiergewehre, which Americans and british traders refused to sell – and alcohol..

Gold[edit]

Already in 1872 there was a brief gold-rush in the Cassiar district. In 1885 gold was discovered along the Stewart River. Campbell already knew about gold in the Fort Selkirk area and Reverend Robert McDonald, was in Fort Yukon from 1862 to 1863 had found gold, probably oon the Birch Creek. George Holt was the first one to send gold from Alaska. Some fur traders changed their business and became prospectors. But this was a bit difficult, because most of them did not want helping hands from the indians. So they preferred doing everything on their own. As a consequence techniques that needed much work – and capital – were not in use. Simple placer mining was the usual way. Ever new rumors of new findings made the men travel around from spot to spot,, and a few women, too.

In 1886 huge amounts of gold were found on the Fortymile River (Ch’ëdäh Dëk) and several hundred men went, where fishing was until then the most promising work. There was also an important path for caribous. The Tr'ondek Hwech'in were capable to feed the new village of Forty Mile and „selling“ furs to them. In exchange they got beads, metal tools and alcohol, goods of high appreciation. Their leader was now Chief Isaac, whose traditional name is forgotten. He was the sun in law of chief Gäh St’ät war.

McQuesten surrendered Fort Reliance (1886) and built a new tradin post on the Stewart River. In 1894 a new post was built about 60 miles upriver from Fort Reliance at the mouth of Sixtymile Creek, which got ist name from William Ogilvie, famous historian of the gold-rush.

On american territory Circle City was built as a consequence of gold-findings on the Birch Creek (1893/94). Findings on the American Creek in 1895 brought up Eagle City, where at a time about a thousand diggers resided.[23] The foundation of Fort Egbert in 1899 was for reasons of surveyance. All in all the number of prospectors had increased to about one or even two thousand.[24], men who pervaded the traditional territory of the Tr'ondek in an uncontrollable way.

Some Tr'ondek worked as packers or carriers on the boats or when it came to mining, but only few of them boought claims. It seems obvious that for them a Lohn very far away in the future was no motivation to carry out the insane and long-lasting work. In addition, they had no plans to leave their homes, and gold was of decreasing purchasing power. In contrast the gold seekers from outsides wanted to leave the area as soon as possible and enjoy a comfortable life in the southern towns.

The wages for the carriers from Dawson to Forty Mile varied between summer and winter times, because in the cold days sled teams allowed higher speed and more luggage or other goods. But they only got a third of the wage. In the mines the indians earned 4 to 8 dollars a day, whites got 6 to 10. The latent racism did not allow them to increase their wages. Anyway the anglican bishop William Carpenter Bompas believed, the indians were growing rich by workin gin the gold-fields and by versorgen of the prospectors and their sled dogs with meat and fish. Some prospectors bought the huts of the indians for 100 or 200 dollars. Inflation was felt in these early days alreday, a phenomenon that the indiains did not know. Under this aspect they chose the worst moment for selling their houses.

Mission, anglican controlling of intercultural contact[edit]

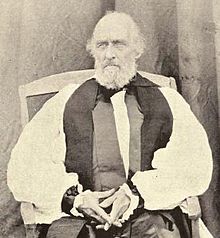

The first missionary was William West Kirkby who came to Fort Youcon in 1862. He stayed for a few days, returned the next year and persuaded a medicine man and four young men to read some texts with him. On the Porcupine River farther north, it was since Robert McDonald, a „half-breed“ from the Red River District, worked as a missionary. In 1864 later bishop Bompas came to the north. In 1876 he became bishop of Athabasca, in 1890 bishop of Selkirk, the later Yukon, a former part of the Mackenzie-diocese.

Besides William Ogilvie and Bernard Moore archdeacon Robert McDonald came iinto the region in 1887. In the same year, anglican missionary J. W. Ellington founded Buxton Mission on Mission Island upriver of Forty Mile, but he had to give uup his plans two years later because of Gesundheitsgründen.

In 1891 bishop William Carpenter Bompas visited the region and returned next year with his wife Charlotte Selina. Besides a brief period iin 1899-1900, when he lived in Moosehide, he lived in Fortymile (Buxton) until l901.

Bompas believed he had to protect the Han, „the lowest of all people“[25], against alcohol abuses and sexual contacts with white fur traders and prospectors as well as against any bad influence. After a contract they held celebrations, during which there was drinking and sexual contacts mit indian women. On the other side, the Han saw that this kind of feasts was not only repeated again and again but also attracted white traders. So they built a dancing hall on Mission Island. Bishop Bompas bought this hoouse and made it a church. [26] The HBC in contrast, promoted this kind of contacts, at least for the lower ranks of their employees. Their aim was to keep the young men in the country. Just the opposte for the higher ranks Alexander Hunter Murray had brought hhis non-indian wife to Fort Youcon in 1847, Robert Campbell was warned by governor George Simpson to complicate his life by marrying an indian woman.[27]

Bishop Bompas opened a school and lobbyed for the presence of the 19 men of the North West Mounted Police under Charles Constantine. Close to Fortymile a fort carrying his name, Fort Constantine was built, the mission on Mission Island was revived. One of his main aims was the segregation of the races.

Bompas was proomoter of a strict antialcohol law, because too many drinking feasts had happened in the few days, when Han and Whites met. As these feasts were the only times when whites saw Han people, they believed, indians were always unmäßig. So they erließen ein Verbot. The police verhängte Bußgelder against traders, who sold their product to indians. But it were these activities that brought together Schwarzbrenner, Schmuggler, fur traders, prospectors and indians.- an unwanted support of alcohol abuse.

In addition missionaries and police men expected violence and were full of puritan fear of sexual contacts and consequently of all feasts. For white men it was the only possibility to get in contact with indian women. The cultural hurds, especially lack of language und knowledge about the culture, the small number of women und the few contact periods made it even more difficult. The contacts were mostly brief, for some men the fear to be called a „Squaw men“ was too strong. The children stayed in most cases with the Han mothers, much more seldom with the white fathers.

Klondike gold-rush, Chief Isaac, Moosehide[edit]

Economic and political dimensions[edit]

The moment of the beginning gold-rush fell into a complex situation. Many countries were introducing the gold standard, which had the task to keep the circulating paper money in a fixed relation to the gold reserves of each country. It was believed that money could be changed into gold at any given time. This dogma made the economic growth dependant on the amoount of gold. The need of gold increased with the growing economies of the industrializing world. Any shortage of gold could become very dangerous under these cicumstances..

In Canada prospectors tried to find more gold, and they found it in a sequence of more or less important gold-rushes starting with the Fraser gold-rush in 1858. These rushes were a kind of massmigration and many men hurried from gold-field to gold-field. The prospectors were highly densified in the western parts of the US and Canada.

Under these circumstances the news of huge gold findings were the starting signal for a massmigration to the hardly populated but difficult to reach areas along the Yukon River. As most of the men came from California this meant a dangerous situation for the Canadian government. It was still in their minds that the british Hudson’s Bay Company, had once lost a large part of ist territories to the US in 1846. Ith ad had to leave behind ist forts in the south. In 1867 the US had bought Alaska and many believed that the whole west, if not the whole of Canada was goiing to be part of the southern neighbour.

Thousands of prospectors made the local indians a minority and also the british living there. When Canada was founded on british initiative in 1867 to Stopp US-expansio to the north, it lasted four years until British Columbia was prepared to become part of the Canadian confederatiion. Canada in 1898 sent a small police unit to the newly founded territory.

A part of the stampeders came through Alaska, which was immediately west of the Klondike area. The department of Department of Alaska developed in 1867, which in 1884 turned into the District of Alaska. Ist harbours offered better access to the Klondike boten, than the ones in Canada. It was impossible to control the border along the 141. Längengrads and for the newcomers it was probably unclear whether they were on US- or on Canadian territory – and it did not matter.

After the panics of 1893 and 1896 the US saw econoomic hardships and repercussions. When the Portland reached Seattle on the 17th of july 1897 and when the first successful prospectors left the ship as rich men, the 5,000 people standing on the shore asked them to show their gold. They presented it to an begeisterte Menge. The Seattle Post-Intelligencer delivered a Klondike-Ausgabe under the Schlagzeile Gold! Gold! Gold! Gold! and Sixty-Eight Rich Men on the Steamer Portland. They had brouoght gold for more thann 700,000 dollars.

Chief Isaac and Moosehide[edit]

In 1894 more than thousand prospectors were in the Yukon. But it was the Klondike gold-rush beginning in1896 that brought more than 100,000 white people into the region. Immediately on the opposite side of the river, opposite the Tr'ondek village Tr'ochëk Dawson was built, the by far largest gold town with more than 40,000 inhabitants at ist peak even more. Joe Ladue sold the lots that he had bought before with high profits. In 1901 indians were only little more than 10 % of the population of Yukon Territory Until the gold-rush Tr'ochëk was the summer camp of chief Isaac. [28], leader of the Tr'ondek Hwech'in. He was born in a village in Alaska[29], which belonged to the US since 1867. He was raised in Eagle Village and in the Forty Mile area. In 1892 he met bishop William Bompas and was baptized. He frrequently participated in services of the Anglican Church, but he also clinged to his traditional values. He often travelled to participate in potlatches in Fort Selkirk, Forty Mile und Eagle, for example, when chief Jackson of the Selkirk First Nation died in 1915.

Bompas gave his watch as a gift shortly before he died, Isaac gave his successor the hunting knife of his grandfather as a counter-gift.

Besides Isaac Silas was chief, possibly a sub-chief, whose duties and rights are unclear. When Isaac was not in Moosehide, Silas vertrat him in 1902; both chiefs were interpreters at the court in Dawson. In 1920 Isaac turned his role as „head potlatch man“ to Chief Silas, as the die Dawson Daily News reported. Many ritual dances took place in the house of Silas who died in the early 1920s.

In 1897 there was a fundamental change. It was anglican missionary Frederick Flewelling, who came back to Tr'ochëk on the 29th of. may 1897 after a winter journey to Forty Mile. The formerly calm village had altered completely, as five to six hundred men had come in spring alone, and their tents were spread everywhere.[30] Speculators had bought the land of many Han, so that they did not know where to stay during the winter. Flewelling bought a tract or 40 Acres two miles downriver, and he proposed to found a mission there and settle the Han in that area.

The remembrances of the Elders reveal another process: They and their chief were still masters of their fate and had invited the newcomers and welcomed them, although they did not understand their greed for gold. Isaac was wondering why they threw away their gold, that they had come into the land only for the gold and believed there were too much of it. He feared the negative conseuquences of contact and he himself made the proposal to go to Moosehide.[31]

Decreasing population[edit]

As before and nearly everywhere in America, deseases played a very important role. The number of Indians in the territory dropped von 3,322 to 1,489 between 1901 and 1911 only..[32] The Han were part of this destruction: They suffered heavy losses from deseases like tuberculosis against which they had hardly any resistance. The hunters of Dawson vertrieben the wildlife, in addition the whites exhausted the forests which they used for buildings and fire. The air was full of smoke, because the prospectors burnt the brushwood and cut down the trunks.[33], the many rafts and boats destroyed their fish traps. Isaac feared brutalization and increasing dependence. Despite all that he kept alive a fragile peace and held lectures.

His personal authority was revealed every morning as he was the first one who was allowed to leave his house, he woke up the village with his strong voice and told his people where to hunt and where to go to.[34] On christmas day 1902 each village elder came to Isaacs house and exchanged gifts.

Moosehide and Dawson[edit]

To avoid conflicts, the Han started negotiations with the church and with the government in the fall of 1896, which means with bishop William Bompas and inspector Charles Constantine. First the Han left Tr’ochëk and went to the Mounted Police reserve on the opposite side of the river, but this reserve was still too close to Dawson.

During the following spring they went some kilometers downriver to Moosehide. The preconditions for such a choice were fresh water from a creek, wood, pathes that allowed hunting and fishing salmon. At the same time they could sell meet to the prospectors and their working power to the owners of the sternwheelers, the saw and lumber mills and of the harbours.

Chief Isaac was very cautious and left a lot of cultural artefacts, especially songs and stories to his kinship in Alaska, to whom he always stayed in close contact. In 1907 for example, he went to Eagle to celebrate a potlatch with chief Alex.

Twelve Mile or Tthedëk was also founded during the gold-rush, because some famiilies did not want to go to Moosehide. At least ten families under chief Charlie Adams and his wife had closer relations to the alaskan groups than to the groups in Dawson, which was about 30 km above their village. Butt his village had to be abandoned; in 1957 it was destroyed by a flooding.

In the meantime, Tr'ochëk was occupied by newcomers beginning in may 1898. Lousetown , also called Klondike City was built. Many prostitutes who were no longer allowed to work in town, went there. Archaeologists found 72 house platforms on the steep slope alone, which carried log cabins. They were befestigt with heavy blocks of rock. Other newcomers simply lived in tents, which left hardly any traces. Litter and sewage simply went down the hill into the river.

In 1898 the number of prospectors increased heavily, als ten thousands of Stampeders came to Dawson. On march 27 of the year 1900 the goverment declared an Indian reserve in Moosehide. But the situation as far as feeding was concerned was so difficult, that Z. T. Wood, Inspector of the North West Mounted Police helped out with flour, rice and tea, to support the 10 to 12 most heavily affected persons.[35]

Isaacs wife, Eliza Harper, was a close friend of Klondike Kate (Kathleen Rockwell), a dancer, who married prospector. She went to Oregon and lived in Bend until she died in 1957. They wrote letters and Kate sent dresses to her friend. She always wrote to „Mrs Chief Isaac“. Eliza became mother of 13 children, of which only 4 grew up. These were Patricia Lindgren, Angela Lopaschuck, Charlie and Fred Isaac. Eliza died in 1960 at the age of 87.

Together with his brother Bruder Walter Benjamin and medicine man Little Paul, Chief Isaac visited his friend Jack McQuesten, who had been a prospector and trader in the Yukon for a long time. For that purpose the three men went with the steamer Sarah down the Yukon to St. Michael, then further on to Seattle, San Francisco and Berkeley in California. They were guests of the Alaska Commercial Company and visited the booms towns along their route.

In 1905 the Yukon Territorial Council feared that a long drought might affect the gold industry. So they were looking for a rain maker, whom they found in Charlie Hatfield. For 10,000 dollars he was supposed to make rain. When only few drops fell, chief Isaac offered four medicine men to show Hatfield how to make rain for only 5,000 dollars.

Between 1904 and 1919 the chief secured four claims for himself, but not for digging for gold, but to secure the settlement fo Moosehide. In 1906 Isaacs oldest sun Edward died from tuberculosis. From 1913 onwards his eight year-old sun visited the Residential School in Carcross. This school, called Choutla School, had opened in 1911. It continued until the early 1960s. In 1920 a house for children of „mixed couples“ was opened, the St Paul's Hostel (until 1952).

Reservatsgrenzen, Auseinandersetzungen[edit]

On december 15, 1911 Chief Isaac in an interview with the Dawson Daily News uttered: „All Klondike belong my people... Long time all mine. Hills all mine, caribou all mine, moose alle mine, rabbits all mine, gold all mine. White men come and take all my gold. Take millions, take more hundreds fifty million, and blow 'em in Seattle. Now Moosehide Injun want Christmas. Game is gone. White man kill all moose and caribou near Dawson... Injun everywhere have own hunting grounds. Moosehides hunt up Klondike, up Sixtymile, up Twentymile, but game is all gone. White man kill all.“ He added that gold-digging was acceptable, slaughtering their fundaments of living not at all.

The resources were dwindling and hunting wanted ever more efforts and longer absence. At the same time steamers and ovens killed the forests around Dawson, so that Isaac tried to protect a forest for the use of his tribe. In 1907 he asked the government via Benjamin Totty for the protection of a forest on Moosehide Creek. At the end of the 1920s the reserve was reduced for the sake of the logging industry, because it was believed that the wood had no meaning for the Han.

Church[edit]

Until 1926 Benjamin Totty, whom Bompas had recruited, was missionary in Moosehide. In remembrance of Bompas the St Barnabas Church was built in 1908. Jonathon Wood, an Indian, worked as a catechist.

The anglican church initiated the Moosehide Men's Club and the Senior Women's Auxiliary. In 1932 was founded probably the only Anglican Young People's Organization in Canada. These institutions were meant to control the moral conduct and the cleanness of the settlement.

Police[edit]

The comptences of the Constable reached much farther. In about 1911 the Mounted Police hired one of the tribe members as a Constable. This Constables, the first whom we come to know of, was Henry Harper. His tasks were very restricted. In 1912 a constable was hired for the only task to prevent the inhabitants of Moosehide to go to Dawson because of a measle epidemic. Chief Isaac became Constable for several times, further names are not known, with the exception of Sam Smith. He was an old Gwich'in from Fort McPherson, who stayed in Moosehide until he died in 1925.

Probably the constables got advice from the Council and the Elders. The so called Special Constables had the task to keep order in Moosehide, a goal which they probably have reached..

First Village Council, Death of Chief Isaac[edit]

In march 1921 the people of Moosehide elected a new council. The chairman was Esau Harper, Chief Isaac became vice-chairman. James Woods was secretary, Sam Smith Inside Guard, David Robert became the guard of the children Tom Young and David Taylor became housekeepers. James Thompson became village inspectore north-end and Peter Thompson south-end. The council saw his tasks in keeping the village clean, to look after old and ill members of the tribe, to make children go to school, to supervise the relations between men and women, and to impose fines, especially against alcohol abuse.

During the first meeting the council forbade young girls to go with whites and banned whites from their reserve. Children were to go to school and should be in bed at nine o’clock. One hour before every Tr’ondek was supposed to leave Dawson, women, who were alone even at 7 o’clock – unless they were accompanied by a married woman. Males were only allowed to overnight when they were in two. They were responsable for producing wood and water for their families. Passing on of chewing tobacco – probably as a pre-caution – was forbidden. It was also forbidden to keep dogs in the house. White were only allowed to come to Moosehide when in business.[36]

There was a certain resistance against these far-going interferences, so the council had to pin its hopes on persuasion rather than punishment. It also reduced its intermingling into the families.

As a whole, indian agent Hawskley said that the Moosehide Council were an experiment, and he resisted proposals from Ottawa to give continuity to the institution.[37]

Isaac lead the tribe until his death on the 9th of apil 1932 and became honorable member of the Yukon Order of Pioneers. He held lots of lessons, e.g. on Victoria Day or Discovery Day. Isaac was frequently a frequently invited guest, although he always remembered his hosts that they were only guests on his land, and that they were butchering his wildlife. He even asked them to abdicate from hunting and fishing as did the Tr'ondek with prospecting. He died on april the 9th of 1932 at the age of 73 from influenza. His corpse was put on a carriage drawn by two horses and brought to Moosehide ovr the ice of the river; all the indians of the area took part in the ceremonies and also many people from Dawson.

His two brothers Johnathon Wood and Walter Benjamin were priests: Johnathon at St. Barnabas Church in Moosehide (he died january 6, 1938 as the oldest inhabitant, Walter Benjamin at the Episcopal Church Mission in Eagle Village, Alaska.

In december 1935 the council held a meeting with indian agent G. Binning for consultations on a difficult theme. The councillors wanted to depose Isaacs successor, Chief Charlie Isaac. Instead the office was again offered to the chief, who obviously was not there too frequently. In january 1936 he was deposed then and John Jonas became the new chief. Charlie Isaac served in wartime between 1939 and 1945 in the canadian army and was stationed in Vancouver and in Victoria. Er starb on 25th february 1975. Seven years before his brother Fred had died. His two sisters Princess Patricia, who went blind very early, and Angela lived until 1991 and 1993. They were sources of oral history of upmost importance. Angela, who lived in Whitehorse, hitch-hiked to Dawson at the age of 73. On her way she spent the nights outdoor.

James or Jimmie Wood, graduate of the Choutla School in Carcross, became chief ca. 1940. He became an anglican catechist, assistant teacher in Moosehide, and he served in a local patrol. He supported a house building program. After ten years of desease he died of tuberculosis in 1956. Second chief was Happy Jack Lesky.

Again, the successor was Chief Jonas, but he was 78 years old. He was the last of the so called Mooshide Chiefs. In 1961 there were only seven families still living there, of whom four were of Han origin, two Peel-River-Gwich'in and a family of mixed ancestry.[38]

Eagle[edit]

The changes with the relatives in Alaska was similarly profound. In may 1898 28 Americans bought a tract of land on Mission Creek. Within a few months their number grew to 1,700, more than 500 log cabins were built. In 1899 Fort Egbert was built to survey and secure the area and the border. We know only from oral sources that the army did not allow the Han to live in their territory any more. Chief Philip, whose house was full of blankets of the Hudson's Bay Company and who owned lots of beads, persuaded his people to go three miles away, where his house stood. They left behind the graves of their ancestors.

In the summer of 1898 the first episcopal bishop of Alaska Peter Trimble Rowe has foreseen a spot for a church, but in the next year Eagle City was occupied by the army. There were also catholics and presbyterians active, so he decided to concentrate his activities on Eagle Village, where the Hans had gone to. Between 1905 and 1906 St. Paul's Mission was built, in 1925 the Indian Walter Benjamin bacame lay preacher. In addition he supported the local missionary until 1946. George Burgess, who lived in the village from 1909 to 1920 as missionary, tried, similarly to Moosehide, to reduce the White men's influence, especially of the soldiers of Fort Egbert. So he terminated the dance feasts. Every male from age 12 had to be a membere of a temperance society - for an entrance fee of one dollar and 25 cent per month as membership fee. They had to promise not to drink any alcohol for a year. In contradiction to Dawson the Han could not buy alcoholic beverages in Eagle City.

In 1902 there was a day-school for the Han childrren in Eagle City, In 1905 the Episcopal Church opened up a day-school in Eagle Village. The school mistress forced the children to solely use English as their language with a cane.[39] At the same time, many children were ill. Tuberculosis, deseases of the lung and of the intestinal tract were widespread. „There was no medicine“, as one of the elders much later remembered. It is unclear how many children died of these deseases. The next hospital was in Fort Youcon or in Dawson.

Hard-money economy[edit]

The money economy reached the area of Dawson all of a sudden, but it did not eliminate barter and exchange of goods at once. The fur trade was rather a kind of barter. The Indians brought food and furs to Forty Mile since 1886. They received glass beads, metal tools and alcohol, only in few cases money. .

The Chilkoot, who had taken control of the passes leading to thea area long before the gold-rush, were the first ones to earn money. They worked as carriers. In the beginning they got 12 cents per pound of the equipment, which the prospectors needed. They carried it over the pass to Lindeman Lake. At the end of the first year of the gold-rush, they took 38 cents already. With bulky goods, like ovens, pianos or wood, they got even more. Sometimes the Chilkoot - at the anger of the prospectors - they went to another prospector, who offered more. The men carried up to 200 pounds, women and adolescents carried about 75 pounds.

But the Indians simply stock-piled their wage, which they got in the form of gold and silver coins. As a consequence there was always a lack of money. They earned between 4 and 8 dollars a day, white workers between 6 and 10. The women also earned quite well, as they additionally sold hats, gloves and mukluks. But the more men without claims were in the Yukkon, the lower the wages were.

In 1872 Leroy Napoleon McQuesten, who preferred the first name „Jack“, and who later was called "father of the Yukon", was working in the Yukon.[40] Born in 1836, he had already looked for gold in 1849 in California. In 1874 he founded the trading post Fort Reliance. Together with his partners he had started a network to supply the prospectors, who came in the following years. In the summer of 1885 McQuesten saw that it was much more promising to trade with the people looking for gold than to trade with furs and the indians. The trading post of Fortymile was the most important spot of supply in the Yukon and the first permanent euro-canadian settlement.

In the spring of 1894 Inspector Constantine and Sergeant Brown were sent to the Yukon by the government, to collect fees and fines.

Until and during the gold-rush money predominantly circulated between traders and prospectors. Only half of them had a claim, the rest of them returned home or sold their working-force and their goods. The more of them left the country, the more the prices for the equipment left behind dropped. Many started digging for loan or offered other services to the claim owners. All in all the stampeders needed 50 million dollars to come to the Klondike - an equivalent to the gold found there during the five years to come.

Along the way between the harbours and Vancouver or Seattle lots of stores were established to supply ten thousands of people. Besides these suppliers other businesses were started that served the men staying for longer, like laundries, barber shops, hotels and soloons or brothels.

Joseph Ladue established a saw-mill in august 1896 at the confluence of Klondike and Yukon River, in addition a ware-house and a saloon. Between 1898 and 1899 a simple, first business structure developed in Dawson. Along the Yukon shops and deposits could be found. Everybody depended on their wares completely, especially during the six months, when no ships reached the town and no wares or money came to the town.

The ones that had no claim or did not look for gold for other reasons were called Cheechako. Some of them produced a market of luxury wares, e.g. for elaborate fassades, but also for music instruments, expensive drapery or jewelry. Buildings like the Bank of Commerce and the atmosphere of the city invited to comparisons. So Dawson became the "Paris of the North".

The more women came to Dawson, the lower the need for laundries or prostitutionn was. The prostitutes had to pay for their allowances, and this money went to institutions of charity, for example hospitals. In may 1899 the women had to leave the core-area and were removed to the area between Fourth and Fifth Avenue. In 1901 they had to go to Klondike City, also called Lousetown, exactly where the Tr'ondek Hwech'in had had their homes.

But the Boom was brief and ended visible for everyone, when the residence of the Commissioners was torn down in 1906. The government did not see a great future for Dawson any more.

The Tr'ondek Hwech'in, who had participated in the trade during the era of Konkurrenz between Tlingit and Hudson's Bay Company in the fur trade, as well as during the brief period of free trade dominated by the Americans could partially earn money as Träger, Schlittenhundeführer, hunters, fisher men or Packer. But during the early period they were just sitting between the monopolies along the Mackenzie River, around Fort Youcon and the Chilkat of the South West.

Now the gold-rush broke into their territory. They found seasonal work at different spots, a fact that supported their traditional life-style. New wares and products needed ever more working force, which itself was in most cases payed work. Subsitence work was in decline. As long as there were not masses of workers in the region, the Tr'ondek found many and easy ways into the labour market.

This equilibrium was destroyed not only by the greed for gold but simply by the masses of immigrants. In 1896 four out of five human beings in the Yukon were Indians - in 1901 only one of nine were Indians.

Workers for simply carrying goods were no longer needed, where railways and steamers replaced their jobs. In addition the Anordnung of the government, which forced every prospector to bring with his own equipment and food, enhanced the need of carriers, but it also reduced the need for hunters and their provisions. Many prospectors started to hunt and became competitors. Sled dogs were heavily in demand, so many people went northwards to buy dogs and sell them at a higher price in Dawson. The steamers could offer simple jobs, and so did the lumber production. Some of the Gwich'in who came southwards, like the Dawson Boys, worked onn the steam boats, some as pilots, some as handymen, but also as carpenters, boat mechanics or licenced traders. Women worked in laundries or as cooks in the camps.

All in all a mixed economy on the basis of the traditional economy emerged, where the men went to their new jobs and occupations in the summer and continued their traditional life-style during the rest of the year with cyclic migrations through their territory.

Women brought clothes to the market, but sleds, snow shoes and mukluks were also in demand. Some of them visited the houses of the prospectors in Forty Mile, and this also happened at Dawson, but on this sector of the economy, new competitors on the sector of prostitution arrived - this in contradiction to most of the other spots, where prospectors had gathered.

Bishop Bompas asserted a limited distribution of welfare for poor Indians, but only the groups of the Bennett Dawson corridor along the police posts could benefit.

The more the industrialization of gold extraction could proceed, the less simple jobs were needed. Education and apprenticeship became more and more important. The labour market for the rest diminished. For the Indians there was hardly any access for technical apprenticeship. In addition there was a continuity of pre-industrial mentality and life-style.

The Klondike gold-rush split the economy into two spheres, the one of gold extraction (later other metals), that means extraction, processing and transportation of raw materials and, on the other side, of hunting, trapping, fishing and gathering. The intersections between the two economies, important in the beginning of the gold-rush, were diminished by and by.

Depression, Alaska Highway[edit]

After 1905 the Tr'ondek were no longer part of the main economic development. Enterprises of the extracting industry were pre-dominant now, the prospector as a cult figure was no longer needed. The three most important of them formed part of the Yukon Consolidated Gold Corporation. Still prospectors searched throughout the territory, but large findings became rare. Instead, copper mines opened near Whitehorse, silver mines near Mayo und Keno. Some Indians like Sam Smith and Big Lake Jim did also work as prospectors und they found gold at Little Atlin. The growing river fleets, which served for the transportation of raw materials, offered opportunities to sell firewood, or rather fuelwood. Still hunting offered opportunities in the Dawson area. In 1904 the town needed 2,300 caribous and 600 mousse with 9,000 inhabitants.[41]

Just like in many branches, indians in the Yukon were pushed aside by the means of legislation. This was a field, where they had no influence. In 1923 they even lost the few opportunities to earn money by guiding hunters, although this was only a small branch. Indians were only allowed as assistant guides and camp aides, but no longer as chief guides.[42] Admittedly there were only three chief guides in 1941, but this field was growing in the 1950s.

One of the oldest branches, the fur industry, was revived - in contradiction to the rest of Canada - to a certain degree. In 1921 there were 27 trading posts of 18 differend enterprises or individuals; in 1930, at the peak, 46 posts of 30 enterprises existed, of which 11 belonged to Taylor and Drury.[43] The market was in heavy fluctuation. The earnings reached their low in 1933 at 23,000 dollars and their high with 600,000 dollars in the years 1944-46.[44] Many hunters were deeply indebted. The territorial government tried to keep off hunters from outside the territory by introducing a fee of 100 dollars for Non-Yukoners . This constrained the Gwich'in - with the exception of the Vuntut Gwitchin, the only Gwich'in group in Yukon.

The Great Depression traf the Tr'ondek because they lost the few jobs within the transportation industry, especially on the steamers that navigated the Yukon and its Nebenflüsse. They were ersetzt by white workers. In addition the mass-Arbeitslosigkeit brought many hunters to the area, which formed a dangerous competition. The fur market fell into a recession at the same tiime. During the fourties the government had to react. Hunting was forbidden now around Dawson to protect the reduced wildlife, especially the caribous. The same picture with the docks and the timber and lumber industries. In addition the last gold mines were closed, many whites left the territory. There were only 2.700 indians left there.

Many Tr'ondek, like 12 men from Eagle Village, became combatants, others went to southern Yukon, where the Alaska Highway was started in 1942, in expectation of a japanese invasion. More than 30,000 workers, most of them from the US, were occupied there. The Canol Road pipeline project offered many new opportunities. In 1942 even a lack of handcraft was felt, as many participated in road construction. As a consequence the mines engagierten indians, but these indians went to traditional hunting and trapping when autumn came. In addition they feared to come into contact with new deseases. Epidemics were still able to kill whole villages like Champagne on Alaska Highway, which is a ghost town today.

In 1947 and 1948 the US fur-market collapsed and so did it with the western Han. It was until 1950 that the so-called trap lines, which were introduced in British Columbia in 1926 already, were distributed. They were supposed to reserve certain areas for indigenous people of certain tribes only, to keep off the white competitors. But the contrary happened. Fees and Vererbung der Anrechte über die männliche Linie, instead of the traditional über die weibliche, led to conflict and as a result in more white competition.

This made the indians even more dependent of canadian welfare, which had been fostered during the war. It reached the Yukon indians from 1955 on. Under-employment and dependence produced an increasing drink problems. The trading of spirits increased where roads were built, e. g. the Taylor Highway, which brought more alcohol to Eagle. In 1964 Eagle Village decided to abolish the trade and sale, a decision still valid today. Despite that the population was still in decline. In 1966 the village had 64 inhabitants, in 1997 only 24. In 2000 there were 30 people living there.

In 1957 the school in Moosehide was closed, the last inhabitants left the village via Dawson. Reverend Martin left the last permanent inhabitants in 1962. But in Dawson the indians did not have the protection of a reserve. They settled in family blocks. The city itself had lost so many people that only few police men were necessary. In 1904 96 men of the North West Mounted Police were in Dawson, in 1910 only 33, in 1925 just 15, and in 1945 no more than 3 were left.[45] The government helped with house construction, but the buildings standing close together quickly formed an indian quarter in Dawson.

Segregation, negligence and disregard[edit]

All in all the anglican church in combination with the police achieved a stage of segregation beginning at about 1905 and lasting until 1942. This would have been impossible without the stereotypes of "savagery" and inferiority within the frame of the white society of the corridor between Dawson, Mayo and Whitehorse. As a consequence there was strong opposition against a school for children of mixed ancestry in Dawson in 1925. On the other hand side every indian woman, who married a white man, lost her status as indian (cf. Indian Act). Besides this the difference in age between the partners rose from 4 years between 1900 and 1925 to 12 years between 1925 and 1950. White men who married indian women were even 16 years older.

There was no legal means to keep the indians away from the towns, as the indian agent of Whitehorse wrote in 1913 with regret, but the "bluff". Indians had to leave Dawson at 7 p.m. in the summer tiime, at 5 p.m. in the winter. They were punished if they did not keep the curfew, if they drank, or simply, if they were too friendly to white inhabitants.[46] From 1929 on indians had to leave Dawson at 8 p.m., in 1933 they needed a special permit, if they wanted to stay in town, which they only got, if they had a working contract. If there was also a bell in Dawson like in Mayo, which announced the curfew, is unclear. A special case were the wives of the missionaries, who were allowed to stay in town, because longtime missionary Toddy was married with an indian, who helped him with his ear problem.

Bibliography[edit]

Zwei weitgehend ethnologische, entgegen dem Titel nur zu einem geringen Teil historische Arbeiten stammen aus den USA, eine ist im Yukon entstanden. Hinzu kommen Arbeiten im Auftrag des Stammes und der Heritage Resources Unit in Whitehorse zur Archäologie, sowie zum Hausbau. Als richtungweisende historische Arbeit für die Zeit von 1840 bis 1973, partiell bis 1990 gilt der Beitrag von Ken S. Coates.

- Chief Isaac, Trondek Heritage (PDF, 588 kB)

- Chris Clarke und K'änächá Group, Sharon Moore (Hg.): Tr'ëhuhch'in näwtr'udäh'¸a = finding our way home, Dawson City, Yukon: Tr'ondëk Hwëch'in Publ., ca. 2009, ISBN 9780968886830

- Ken S. Coates: Best Left as Indians. Native-White Relations in the Yukon Territory, 1840-1973, Montreal, Kingston: McGill-Queen's University Press 1991, Paperback 1993.

- Helene Dobrowolsky: Hammerstones: A History of the Tr'ondek Hwech'in, Tr'ondek Hwech'in Han Nation 2003

- Helene Dobrowolsky: Tr'ondëk Hwëch'in (First Nation) Yukon Territory. Forty Mile Historic Site: bibliography: archival sources for Forty Mile, Fort Constantine and Fort Cudahy Historic Site / zusammengestellt für Tr'ondëk Hwëch'in, Whitehorse: Yukon Government, Heritage Resources Unit 2002

- Thomas J. Hammer, Christian D. Thomas: Archaeology at Forty Mile/C'hëdä Dëk, Whitehorse: Yukon Tourism and Culture 2006

- Innovative Buildings. Homes for the Tr'ondëk Hwëch'in Hän. FlexHousingTM in Dawson City

- Craig Mishler, William E. Simeone: Han, People of the River: Hän Hwëch'in: An Ethnography and Ethnohistory, University of Alaska Press 2004, ISBN 1-889963-41-0

- Cornelius Osgood: The Han Indians: A Compilation of Ethnographic & Historical Data on the Alaska-Yukon Boundary Area, Yale University Publications in Anthropology 1971 - Osgood versucht die Kultur der Han um 1850, also zum Zeitpunkt der ersten direkten Kontakte mit Europäern, darzustellen.

- Adney Tappan: The Klondike Stampede, University of British Columbia 1994, ISBN 978-0-7748-0490-5

External links[edit]

- Website der Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in First Nation

- Tr'ondëk Hwëch'in Heritage Sites

- Chief Isaac - Tr'ondek Hwech'in - People of the River - Website mit dem Schwerpunkt Chief Isaac, seit Juli 2009

- MacBride Museum of Yukon History

References[edit]

- ^ Ein Foto Chief Isaacs von 1898 findet sich hier: Chief Isaac of the Han, Yukon Territory, ca. 1898, in: University of Washington, Digital Collections.

- ^ Zu den Besonderheiten archäologischer Stätten in Yukon vgl. Ruth Gotthardt: Handbook for the Identification of Heritage Sites and Features, S. 1 (PDF, 3,3 MB).

- ^ Erstere umfasst heute über 100.000 Tiere, letztere wird für die Zeit um 1900 auf 600.000 Tiere geschätzt. 2007 wurde die Herde auf 110.000 bis 112.000 Tiere geschätzt, 2001 auf 123.000. Vgl. Porcupine Caribou Management Board. No Porcupine Caribou census this year – again und 40 Mile caribou herd crossing near Dawson, CBC, 29. Oktober 2007. Allgemeiner: Rick Bass: Caribou Rising: Defending the Porcupine Herd, Gwich'in Culture, and the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, ISBN 978-1-578-0511-44.

- ^ Dies und das Folgende nach Helene Dobrowolsky/T. J. Hammer: Tr'ochëk - The Archaeology and History of a Hän Fish Camp, 2001

- ^ Mishler/Simeone, S. 44.

- ^ K. D. West, J. D. Donaldson: Evidence for winter eruption of the White River Ash (eastern lobe), Yukon Territory, Canada. Abstract, 2000.

- ^ Die Mahoney tauchen nur in Berichten des Department of Indian Affairs aus den Jahren 1869 auf (Frederick Webb Hodge (Hrsg.): Handbook of American Indians North of Mexico, Bd. 1, Nachdruck der Ausgabe von 1912, Smithsonian Institute 2003, Teil 1, S. 31 und Teil 2, S. 734).

- ^ Ein solches Boot aus dem Raum Fort Selkirk findet sich hier.

- ^ Julie Cruikshank: Life Lived Like a Story: Life Stories of Three Yukon Native Elders, University of Nebraska Press 1990, S. 8.

- ^ Shepard Krech III: The Death of Barbue, a Kutchin Trading Chief, in: Arctic 35/2 (1962) 429-437.

- ^ James Mooney: The Aboriginal Population of America North of Mexico, Smithsonian Miscellaneous Collections, 80, 2955 (1928) 1-40, Washington

- ^ Robert Boyd: The coming of the spirit of pestilence. Introduced infectious diseases and population decline among Northwest Coast Indians, 1774-1874, University of Washington Press, Seattle 1999, p. 23f.

- ^ Mishler/Simeone, p. 36.

- ^ Coates, p. 8-14.

- ^ Osgood, S. 3.

- ^ Osgood, S. 5.

- ^ Dies und das Folgende nach Osgood, S. 5ff. und Early Traders and Steamboats

- ^ Osgood, S. 5.

- ^ Osgood, S. 8.

- ^ Nach Osgood: Bonfield.

- ^ McQuiston, S. 104. Archäologische Untersuchungen führten zu dem Ergebnis, dass die Fläche bei genau 29,4 * 20,4 Fuß lag, das Haus wies also kaum 70 m² Grundfläche auf.

- ^ Osgood, S. 12.

- ^ Osgood, S. 12.

- ^ Mishler/Simeone, S. 14.

- ^ Zitiert nach Coates, S. 78.

- ^ Dies und das Folgende nach Coates, S. 79ff.

- ^ Coates, S. 76.

- ^ Dies und das Folgende nach Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in Interpretive Manual, Abschnitt Chief Isaac

- ^ Unklar ist, ob Isaac aus der oberen Tananaregion, Ketchumstock, Tanacross oder Chena stammte.

- ^ Mishler/Simeone S. 20f.

- ^ That is what a daughter of chief Isaacs told (Mishler/Simeone S. 22).

- ^ Coates, Table 7, p. 74.

- ^ Kathryn Taylor Morse: The Nature of Gold. An Environmental History of the Klondike Gold Rush, Weyerhaeuser Environmental Books 2003, S. 95, ISBN 9780295983295

- ^ Mishler/Simeone, S. 109.

- ^ Coates, S. 172.

- ^ Coates, S. 177, Mishler/Simeone, S. 23.

- ^ Coates, S. 304 Anm. 105.

- ^ Osgood, S. 18.

- ^ Mishler/Simeone, S. 26f.

- ^ James A. McQuiston: Captain Jack McQuesten: Father of the Yukon, Outskirts Press 2007.

- ^ Coates, p. 50. But in 1921 only 7 of 53 hunting licenses were in indian hands, and these few lived in the Mayo area. It is true that most indians did not buy a license, instead they sold to individuals, but the shere numbers show that white competition was strong.

- ^ Yukon Territorial Game Ordinance.

- ^ Coates, S. 56f.

- ^ Coates, p. 58, Table 4.

- ^ Coates, Table 28, S. 181.

- ^ Coastes, p. 94.