Vietnam War casualties

Estimates of casualties of the Vietnam War vary widely. Estimates include both civilian and military deaths in North and South Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia.

The war persisted from 1955 to 1975 and most of the fighting took place in South Vietnam; accordingly it suffered the most casualties. The war also spilled over into the neighboring countries of Cambodia and Laos which also endured casualties from aerial and ground fighting.

Civilian deaths caused by both sides amounted to a significant percentage of total deaths. Civilian deaths were partly caused by assassinations, massacres and terror tactics. Civilian deaths were also caused by mortar and artillery, extensive aerial bombing and the use of firepower in military operations conducted in heavily populated areas. Some 365,000 Vietnamese civilians are estimated by one source to have died as a result of the war during the period of American involvement.[1]

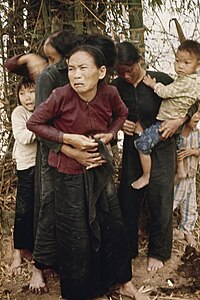

A number of incidents occurred during the war in which civilians were deliberately targeted or killed. The best-known are the Massacre at Huế and the My Lai massacre.

Total number of deaths

Estimates of the total number of deaths in the Vietnam War vary widely. The wide disparity among the estimates cited below is partially explained by the different time periods of the Vietnam War covered by the studies and whether casualties in Cambodia and Laos were included in the estimates.

Guenter Lewy in 1978 estimated 1,353,000 total deaths in North and South Vietnam during the period 1965–1974 in which the U.S. was most engaged in the war. Lewy reduced the number of VC and PAVN battle deaths claimed by the U.S. by 30 percent (in accordance with the opinion of United States Department of Defense officials), and assumed that one third of the battle deaths of the PAVN/VC were actually civilians. His estimate of total deaths is reflected in the table.[2]

| Allied military deaths | 282,000 |

|---|---|

| NVA/VC military deaths | 444,000 |

| Civilian deaths (North and South Vietnam) | 627,000 |

| Total deaths | 1,353,000 |

A 1995 demographic study in Population and Development Review calculated 791,000–1,141,000 war-related Vietnamese deaths, both soldiers and civilians, for all of Vietnam from 1965–75. The study came up with a most likely Vietnamese death toll of 882,000, which included 655,000 adult males (above 15 years of age), 143,000 adult females, and 84,000 children. Those totals include only Vietnamese deaths, and do not include American and other allied military deaths which amounted to about 64,000.[3] The study has been criticized for its small sample size, the imbalance in the sample between rural and urban areas, and the possible overlooking of clusters of high mortality rates.[4]

In 1995, the Vietnamese government released its estimate of war deaths for the more lengthy period of 1955–75. PAVN and VC deaths were reported as 1.1 million and civilian deaths of Vietnamese on both sides totaled 2.0 million. These estimates probably include deaths of Vietnamese soldiers in Laos and Cambodia, but do not include deaths of South Vietnamese and allied soldiers which would add nearly 300,000 for a grand total of 3.4 million military and civilian dead.[5]

A 2008 study by the BMJ (formerly British Medical Journal) came up with a higher toll of 3,812,000 dead in Vietnam between 1955–2002. For the period of the Vietnam War the totals are 1,310,000 between 1955 and 1964, 1,700,000 between 1965–74 and 810,000 between 1975 and 1984. (The estimates for 1955–64 are much higher than other estimates). The sum of those totals is 3,091,000 war deaths between 1955–75.[4]

Uppsala University in Sweden maintains the Armed Conflict Database. Their estimates for conflict deaths in Vietnam are 164,923 from 1955–64 and 1,458,050 from 1965–75 for a total of 1,622,973. The database also estimates combat deaths in Cambodia for the years 1967–75 to total 259,000. Data for deaths in Laos is incomplete.[6]

R. J. Rummel's mid-range estimate in 1997 was that the total deaths due to the Vietnam War totaled 2,450,000 from 1954–75. Rummel calculated PAVN/VC deaths at 1,062,000 and ARVN and allied war deaths of 741,000,with both totals include civilians inadvertently killed. He estimated that victims of democide (deliberate killing of civilians) included 214,000 by North Vietnam/VC and 98,000 by South Vietnam and its allies. Deaths in Cambodia and Laos were estimated at 273,000 and 62,000 respectively.[7]

| Low estimate of deaths | Middle estimate of deaths | High estimate of deaths | Notes and comments | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| North Vietnam/Viet Cong military and civilian war dead | 533,000 | 1,062,000 | 1,489,000 | includes an estimated 50,000/65,000/70,000 civilians killed by U.S/SVN bombing/shelling[8] |

| South Vietnam/U.S./South Korea war military and civilian war dead | 429,000 | 741,000 | 1,119,000 | includes 360,000/391,000/720,000 civilians[9] |

| Democide by North Vietnam/Viet Cong | 131,000 | 214,000 | 302,000 | 25,000/50,000/75,000 killed in North Vietnam, 106,000/164,000/227,000 killed in South Vietnam |

| Democide by South Vietnam | 57,000 | 89,000 | 284,000 | Democide is the murder of persons by or at the behest of governments. |

| Democide by the United States | 4,000 | 6,000 | 10,000 | Democide is the murder of persons by or at the behest of governments. |

| Democide by South Korea | 3,000 | 3,000 | 3,000 | Rummel does not give a medium or high estimate. |

| Subtotal Vietnam | 1,156,000 | 2,115,000 | 3,207,000 | |

| Cambodians | 273,000 | 273,000 | 273,000 | Rummel estimates 212,000 killed by Khmer Rouge (1967–1975), 60,000 killed by U.S. and 1,000 killed by South Vietnam (1967–73). No estimate given for deaths caused by Viet Cong/North Vietnam (1954–75).[10] |

| Laotians | 28,000 | 62,000 | 115,000 | Source:[4] |

| Grand total of war deaths: Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos (1954–75) | 1,450,000 | 2,450,000 | 3,595,000 |

Civilian deaths in the Vietnam War

Lewy estimates that 40,000 South Vietnamese civilians were assassinated by the PAVN/VC; 250,000 were killed as a result of combat in South Vietnam, and 65,000 were killed in North Vietnam. He suggests that another 222,000 civilians were counted as military deaths by the U.S. in compiling its "body count." His estimated total of civilian deaths is 587,000.[11][12][13] It was difficult to distinguish between civilians and military personnel in many instances as many individuals were part-time guerrillas or impressed laborers who did not wear uniforms.[14][15][16]

Deaths caused by North Vietnam/VC forces

R. J. Rummel estimated that PAVN/VC forces killed around 164,000 civilians in democide between 1954 and 1975 in South Vietnam, from a range of between 106,000 and 227,000, plus another 50,000 killed in North Vietnam.[17] Rummel's mid-level estimate includes 17,000 South Vietnamese civil servants killed by PAVN/VC. In addition, at least 36,000 Southern civilians were executed for various reasons in the period 1967–1972.[18] About 130 American and 16,000 South Vietnamese POWs died in captivity.[19] During the peak war years, another scholar Guenter Lewy attributed almost a third of civilian deaths to the VC.[20]

Thomas Thayer in 1985 estimated that during the 1965–72 period the VC killed 33,052 South Vietnamese village officials and civil servants.[21]

Deaths caused by South Vietnam

According to RJ Rummel, from 1964 to 1975, an estimated 1,500 people died during the forced relocations of 1,200,000 civilians, another 5,000 prisoners died from ill-treatment and about 30,000 suspected communists and fighters were executed. In Quảng Nam Province 4,700 civilians were killed in 1969. This totals, from a range of between 16,000 and 167,000 deaths caused by South Vietnam during the (Diệm-era), and 42,000 and 118,000 deaths caused by South Vietnam in the post Diệm-era), excluding PAVN forces killed by the ARVN in combat.[22] Operating under the direction of the CIA and other US and South Vietnamese Intel organizations and carried out by RVN units alongside US advisers was the Phoenix Program, intended to neutralise the VC political infrastructure, whom were the civilian administration of the Viet Cong/Provisional Revolutionary Government via infiltration, capture, counter-terrorism, interrogation, and assassination.[23] The program resulted in an estimated 26,000 to 41,000 killed, with an unknown number possibly being innocent civilians.[23]

Deaths caused by the American military

RJ Rummel estimated that American forces committed around 5,500 intentional democidal mass-killings between 1960 and 1972, from a range of between 4,000 and 10,000 killed in democide.[24] Benjamin Valentino attributes possibly 110,000–310,000 "counterguerrilla mass killings" to U.S. and South Vietnamese forces during the war.[25]

Estimates for the number of North Vietnamese civilian deaths resulting from US bombing range from 30,000–65,000.[26][3] Higher estimates place the number of civilian deaths caused by American bombing of North Vietnam in Operation Rolling Thunder at 182,000.[27] American bombing in Cambodia is estimated to have killed between 30,000 and 150,000 civilians and combatants.[25][28]

18.2 million gallons of Agent Orange, some of which was contaminated with Dioxin, was sprayed by the U.S. military over more than 10% of Southern Vietnam,[31] as part of the U.S. herbicidal warfare program, Operation Ranch Hand, during the Vietnam War from 1961 to 1971. Vietnam's government claimed that 400,000 people were killed or maimed as a result of after effects, and that 500,000 children were born with birth defects.[32] The United States government has challenged these figures as being unreliable.[33]

Guenter Lewy estimates that around 220,000 civilians in South Vietnam were killed in US, ARVN and other allied land operations and miscounted as "enemy KIA".[34] For official US military operations reports, there are no established distinctions between enemy KIA and civilian KIA, since body counts was a direct measure of operational success often caused US "operations reports" to list civilians killed as enemy KIA.[35] The pressure to produce body counts as a measure of operational success often caused US "operations reports" to list civilians killed as enemy KIA[36] with one prominent example being the My Lai Massacre written off as an operational success.[37][38] It was assumed by US forces that, where an area was declared a free-fire zone that all individuals killed regardless of whether they were combatants or not, were considered enemy killed in action.[39] This it is suggested explains the discrepancies between recovered weapons and body-count figures, alongside inflation, however the NVA and VC always went to great lengths to recover weapons from the battlefield.[34] Official operations reports rarely made a distinction between civilians killed and actual combatants, drastically inflating the numbers of "enemies killed" as it was directly tied to promotions and commendation.[40][38] At other times US-committed atrocities were often tied to or blamed on the NVA/VC to skirt punishment.[40] There are further claims made that when air-strikes or artillery were called in on villages, usually civilian casualties were reported as "enemies killed".[40][38][41]

German historian Bernd Greiner mentions the following war crimes reported, and/or investigated by the Peers Commission and the Vietnam War Crimes Working Group, among other sources:[42]

- Seven massacres officially confirmed by the American side. My Lai (4) and My Khe (4) (collectively the My Lai Massacre) claimed the largest number of victims with 420 and 90 respectively, and in five other places altogether about 100 civilians were executed.

- Two further massacres were reported by soldiers who had taken part in them, one north of Đức Pho in Quảng Ngãi Province in the summer of 1968 (14 victims), another in Bình Định Province on 20 July 1969 (25 victims).[citation needed]

- Tiger Force, a special operations force, murdered hundreds, possibly over a thousand, civilians.

According to the Information Bureau of the Provisional Revolutionary Government of South Vietnam (PRG), between April 1968 and the end of 1970 American ground troops killed about 6,500 civilians in the course of twenty-one operations either on their own or alongside their allies. Three of the massacres reported on the American side were not mentioned on the PRG list.

Nick Turse, in his 2013 book, Kill Anything that Moves, argues that a relentless drive toward higher body counts, a widespread use of free-fire zones, rules of engagement where civilians who ran from soldiers or helicopters could be viewed as VC, and a widespread disdain for Vietnamese civilians led to massive civilian casualties and endemic war crimes inflicted by U.S. troops.[43] One example cited by Turse is Operation Speedy Express, an operation by the 9th Infantry Division, which was described by John Paul Vann as, in effect, "many My Lais".[43]

Air force captain, Brian Wilson, who carried out bomb-damage assessments in free-fire zones throughout the delta, saw the results firsthand. "It was the epitome of immorality...One of the times I counted bodies after an air strike—which always ended with two napalm bombs which would just fry everything that was left—I counted sixty-two bodies. In my report I described them as so many women between fifteen and twenty-five and so many children—usually in their mothers' arms or very close to them—and so many old people." When he later read the official tally of dead, he found that it listed them as 130 VC killed.[44]

Deaths caused by the South Korean military

The ROK Capital Division purportedly conducted the Bình An/Tây Vinh massacre in February/March 1966. The 2nd Marine Brigade purportedly conducted the Binh Tai Massacre on 9 October 1966.[46] In December 1966, the Blue Dragon Brigade purportedly conducted the Bình Hòa massacre.[47] The Second Marine Brigade conducted the Phong Nhị and Phong Nhất massacre on 12 February 1968.[48][49] South Korean Marines purportedly conducted the Hà My massacre on 25 February 1968.[50] According to a study conducted in 1968 by a Quaker-funded Vietnamese-speaking American couple, Diane and Michael Jones, there were at least 12 mass-killings conducted by South Korean forces which approached the scale of the My Lai Massacre with reports of thousands of routine murders on civilians primarily the elderly, women and children.[51][52] A separate study by a RAND Corporation employee Terry Rambo conducted interviews in 1970 in ARVN/civilian areas on reported Korean atrocities.[53] Widespread reports of deliberate mass-killings were reported to have occurred, alleging that these were systemic, deliberate policies to massacre civilians with murders running into the hundreds.[53] These policies are also reported by US commanders, with one US Marine General stating "whenever the Korean marines received fire "or think (they got) fired on from a village ... they'd divert from their march and go over and completely level the village ... it would be a lesson to (the Vietnamese)."[54] Another Marine commander Gen. Robert E. Cushman Jr. added, "we had a big problem with atrocities attributed to them, which I sent on down to Saigon."[54] Investigations by Korean civic groups have alleged there were at-least 9000 civilians massacred by ROK forces.[55]

Army of the Republic of Vietnam

The ARVN suffered 254,256 recorded combat deaths between 1960 and 1974, with the highest number of recorded deaths being in 1972, with 39,587 combat deaths.[56] According to Guenter Lewy, the ARVN suffered between 171,331 and 220,357 deaths during the war.[11][21]: 106 R.J. Rummel estimated that ARVN suffered between 219,000 and 313,000 deaths during the war including in 1975 and prior to 1960.[17]

| Year | 1960 | 1961 | 1962 | 1963 | 1964 | 1965 | 1966 | 1967 | 1968 | 1969 | 1970 | 1971 | 1972 | 1973 | 1974 | Total (1960–1974) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ARVN combat deaths[57] | 2,223 | 4,004 | 4,457 | 5,665 | 7,457 | 11,242 | 11,953 | 12,716 | 27,915 | 21,833 | 23,346 | 22,738 | 39,587 | 27,901 | 31,219 | 254,256 |

North Vietnamese and Viet Cong military deaths

According to the Vietnamese government's national survey and assessment of war casualties (2017), there were 849,018 PAVN/VC military personnel dead, including combat death and non-combat death, from the period between 1955 and 1975.[58] Based on unit surveys, a rough estimate of 30–40% of dead and missing were non-combat deaths.[58] Across all three wars including the First Indochina War and the Third Indochina War there was a total of 1,146,250 PAVN/VC military deaths or missing, included 939,460 deaths (their bodies were found) and 207,000 missing (their bodies were not found). Per war: 191,605 deaths/missing in the First Indochina War, 849,018 deaths/missing in the Second Indochina War (Vietnam War), and 105,627 deaths/missing in the Third Indochina War.[58] It is unclear how the Vietnamese Government figures correlate to other reports of 300-330,000 PAVN/VC missing-in-action from the Vietnam War.[59] Per the official history, one of the deadliest years was 1972, in which the PAVN suffered over 100,000 deaths.[60] After the U.S.'s withdrawal from the conflict, the Pentagon estimated PAVN deaths at 39,000 in 1973 and 61,000 in 1974.[61]

There has been considerable controversy about the exact numbers of deaths inflicted on the Communist side by U.S. and allied South Vietnamese forces. Shelby Stanton, writing in The Rise and Fall of an American Army, declined to include casualty statistics because of their 'general unreliability.' Accurate assessments of NV Army and Viet Cong losses, he wrote, were 'largely impossible due to lack of disclosure by the Vietnamese government, terrain, destruction of remains by firepower, and [inability] to confirm artillery and aerial kills.' The 'shameful gamesmanship' practiced by 'certain reporting elements' under pressure to 'produce results' also shrouded the process.[62]

RJ Rummel estimates 1,011,000 PAVN/VC combatant deaths.[63] The official US Department of Defense figure was 950,765 communist forces killed in Vietnam from 1965 to 1974. Defense Department officials believed that these body count figures need to be deflated by 30 percent. For this figure, Guenter Lewy assumes that one-third of the reported enemy killed may have been civilians, concluding that the actual number of deaths of the VC and PAVN military forces was probably closer to 444,000.[11]

Author Mark Woodruff noted that when the Vietnamese Government finally revealed its losses (in April 1995) as being 1.1 million dead, US body count figures had actually underestimated enemy losses.[64]

The Phoenix Program, a counterinsurgency program executed by the United States Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), United States special operations forces, and the Republic of Vietnam's security apparatus, killed 26,369 suspected of being VC operatives and informants.[65][66]

Historian Christian Appy states "search and destroy was the principal tactic; and the enemy body count was the primary measure of progress" in the US strategy of attrition. Search and destroy was a term to describe operations aimed at flushing the Viet Cong out of hiding, while body count was the measuring stick for operation success. Competitions were held between units for the highest number of Vietnamese killed. U.S. Army and marine officers knew that promotions were largely based on confirmed kills. The pressure to produce confirmed kills resulted in massive fraud. One of the most thorough studies found that American commanders exaggerated body counts by 100 percent. Furthermore there was little distinction made between armed combatants, neutral civilians and unarmed individuals for "enemy KIA".[67]

United States armed forces

Casualties as of 26 July 2019:

- 58,318 KIA or non-combat deaths (including the missing and deaths in captivity)[68]

- 153,303 WIA (excluding 150,332 persons not requiring hospital care)[69]

- 1,587 MIA (originally 2,646)[70]

- 766–778 POW (652–662 freed/escaped*,[71][72] 114–116 died in captivity)[71][73]

Note: *One escapee died of wounds sustained during his rescue 15 days later.[74]

The total number of American personnel who were KIA or died non-hostile deaths, were enlisted personnel with a casualty number of 50,441. The total number of officer casualties,commissioned and warrant, are 7,877. The following is a chart of all casualties, listed by race, and in descending order. [75]

| WHITE | BLACK | HISPANIC | HI/PAC. ISLANDER | AMERICAN INDIAN/ALASKA NATIVE | NON-HISPANIC (OTHER RACE) | ASIAN |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 49,830 | 7,243 | 349 | 229 | 226 | 204 | 139 |

The total number of casualties, both KIA and non-hostile deaths, for drafted and volunteer service personnel (figures are approximated): [76]:

| Volunteer | Draftees |

|---|---|

| 70% | 30% |

During the Vietnam War, 30% of wounded service members died of their wounds.[77] 30–35% of American deaths in the war were non-combat or friendly fire deaths; the largest causes of death in the U.S. armed forces were small arms fire (31.8%), booby traps including mines and frags (27.4%), and aircraft crashes (14.7%).[78]

Disproportion of African American casualties

African Americans suffered disproportionately high casualty rates in Vietnam. In 1965 alone they comprised 14.1% of total combat deaths, when they only comprised approximately 11% of the total U.S. population in the same year.[79][80] With the draft increasing due to the troop buildup in South Vietnam, the military significantly lowered its admission standards. In October 1966, Defense Secretary Robert McNamara initiated Project 100,000 which further lowered military standards for 100,000 additional draftees per year. McNamara claimed this program would provide valuable training, skills and opportunity to America's poor – a promise that was never carried out. Many black men who had previously been ineligible could now be drafted, along with many poor and racially intolerant white men from the southern states. This led to increased racial tension in the military.[81][82]

The number of US military personnel in Vietnam jumped from 23,300 in 1965 to 465,600 by the end of 1967. Between October 1966 and June 1969, 246,000 soldiers were recruited through Project 100,000, of whom 41% were black, while blacks only made up about 11% of the population of the US.[81] Of the 27 million draft-age men between 1964 and 1973, 40% were drafted into military service, and only 10% were actually sent to Vietnam. This group was made up almost entirely of either work-class or rural youth. College students who did not avoid the draft were generally sent to non-combat and service roles or made officers, while high school drop-outs and the working class were sent into combat roles. Blacks often made up a disproportionate 25% to 80% or more of combat units, while constituting only 12% of the military. 20% of black males were combat soldiers, sailors, airmen and marines.[79][83]

Civil rights leaders including Martin Luther King Jr., Malcolm X, John Lewis, Muhammad Ali, and others, criticized the racial disparity in both casualties and representation in the entire military, prompting the Pentagon to order cutbacks in the number of African Americans in combat positions. Commander George L. Jackson said, "In response to this criticism, the Department of Defense took steps to readjust force levels in order to achieve an equitable proportion and employment of Negroes in Vietnam." The Army instigated myriad reforms, addressed issues of discrimination and prejudice from the post exchanges to the lack of black officers, and introduced "Mandatory Watch And Action Committees" into each unit. This resulted in a dramatic decrease in the proportion of black casualties, and by late 1967, black casualties had fallen to 13%, and were below 10% in 1970 to 1972.[81][84] As a result, by the war's completion, total black casualties averaged 12.5% of US combat deaths, approximately equal to percentage of draft-eligible black men, though still slightly higher than the 10% who served in the military.[84]

Aftereffects

Unexploded ordnance, especially bombs dropped by the United States, continue to detonate and kill people today. The Vietnamese government claims that unexploded ordnance has killed some 42,000 people since the official end of the war.[85][86] In 2012 alone, unexploded bombs and other ordnance claimed 500 casualties in Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia, according to activists and government databases. The United States has spent over $65 million since 1998 in an attempt to make Vietnam safe.[87]

Agent Orange and similar chemical defoliants have also caused a considerable number of deaths and injuries over the years, including among the US Air Force crew that handled them. The government of Vietnam says that 4 million of its citizens were exposed to Agent Orange, and as many as 3 million have suffered illnesses because of it; these figures include the children of people who were exposed.[88] The Red Cross of Vietnam estimates that up to 1 million people are disabled or suffer health problems due to Agent Orange exposure.[89]

On 9 August 2012, the United States and Vietnam began a cooperative cleaning up of the toxic chemical from part of Da Nang International Airport, marking the first time Washington has been involved in cleaning up Agent Orange in Vietnam. Da Nang was the primary storage site of the chemical. Two other cleanup sites being reviewed by the United States and Vietnam are Biên Hòa Air Base, in the southern province of Đồng Nai – a 'hotspot' for dioxin – and Phù Cát Air Base in Bình Định Province, according to U.S. Ambassador to Vietnam David Shear. The Vietnamese newspaper Nhân Dân reported in 2012 that the U.S. government was providing $41 million to the project, which aimed to reduce the contamination level in 73,000 m³ of soil by late 2016.[90]

Other nations' casualties

- 20,000–62,000 killed[4]

Military

South Korea

- 5,099 Killed in action

- 14,232 wounded

- 4 missing in action[94]

Australia

- 426 killed in action, 74 died of other causes[95]

- 3,129 wounded[95]

- 6 missing in action (all accounted for and repatriated)[96]

Thailand

New Zealand

Philippines

- 25 people killed in action and 1 mongoose[citation needed]

People's Republic of China

- 1,446 killed in action[101]

Soviet Union

- ~16[102]

Great Britain

- ~1[citation needed]

References

- ^ Walter Russell Mead (13 May 2013). Special Providence: American Foreign Policy and How It Changed the World. Routledge. pp. 219–. ISBN 978-1-136-75867-6.

- ^ Lewy, Guenter (1978), America in Vietnam, New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 442–453

- ^ a b Charles Hirschman et al., Vietnamese Casualties During the American War: A New Estimate, Population and Development Review, December 1995.

- ^ a b c d Obermeyer, Ziad; Murray, Christopher J. L.; Gakidou, Emmanuela (2008). "Fifty years of violent war deaths from Vietnam to Bosnia: analysis of data from the world health survey programme". BMJ. 336 (7659): 1482–1486. doi:10.1136/bmj.a137. PMC 2440905. PMID 18566045.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) See Table 3 for most estimates. - ^ Shenon, Philip, "20 Years After Victory, Vietnamese Communists Ponder How to Celebrate, The New York Times, 23 April 1995

- ^ "UCDP/Prio Armed Conflict Database", Uppsala University, http://www.pcr.uu.se/research/ucdp/datasets/ucdp_prio_armed_conflict_dataset/ Archived 2015-08-11 at the Wayback Machine, accessed 24 Nov 2014

- ^ a b Rummel, R. J. "Statistics of Vietnamese Democide", Lines 777–785, http://www.hawaii.edu/powerkills/SOD.TAB6.1B.GIF, accessed 24 Nov 2014

- ^ Rummel, 1997, line 61

- ^ Rummel, 1997, line 117

- ^ https://www.hawaii.edu/powerkills/DBG.TAB9.1.GIF, accessed 24 Nov 2014

- ^ a b c Lewy, Guenter (1978). America in Vietnam. New York: Oxford University Press. Appendix 1, pp.450–453

- ^ Thayer, Thomas C (1985). War Without Fronts: The American Experience in Vietnam. Boulder: Westview Press. Ch. 12.

- ^ Wiesner, Louis A. (1988). Victims and Survivors Displaced Persons and Other War Victims in Viet-Nam. New York: Greenwood Press. p.310

- ^ Willbanks, James H. (2008). The Tet Offensive: A Concise History. New York: Columbia University Press. p. 32. ISBN 978-0-231-12841-4.

- ^ Rand Corporation [http://www.dtic.mil/dtic/tr/fulltext/u2/a032189.pdf Some Impressions of Viet Cong Vulnerabilities an Interim Report 1965

- ^ James J. F. Forest Countering Terrorism and Insurgency in the 21st Century 2007 ISBN 978-0275990343

- ^ a b Rummel 1997

- ^ Michael Lee Lanning and Dan Cragg, Inside the VC and the NVA, (Ballantine Books, 1993), pp. 186–188

- ^ Rummel 1997, Lines 457 & 459.

- ^ Lewy, Guentner (1978), America in Vietnam New York: Oxford University Press., pp.272–3, 448–9.

- ^ a b Thayer, Thomas (1985). War without Fronts: The American experience in Vietnam. Westview Press. p. 51. ISBN 9781612519128.

- ^ Rummel 1997 Lines 521, 540, 556, 563, 566, 569, 575

- ^ a b Miller, Edward (2017-12-29). "Opinion | Behind the Phoenix Program". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2018-06-03.

- ^ Rummel 1997 Lines 613]

- ^ a b Valentino, Benjamin (2005). Final Solutions: Mass Killing and Genocide in the 20th Century. Cornell University Press. p. 84. ISBN 9780801472732.

- ^ Tucker, Spencer, ed. (2011). Encyclopedia of the Vietnam War: A Political, Social, and Military History. Volume Two. Santa Barbara, CA, p. 176

- ^ "Battlefield:Vietnam Timeline". Pbs.org. Retrieved 31 October 2011.

- ^ Kiernan, Ben; Owen, Taylor. "Bombs over Cambodia" (PDF). The Walrus (October 2006): 62–69. "Previously, it was estimated that between 50,000 and 150,000 Cambodian civilians were killed by the bombing. "Given the fivefold increase in tonnage revealed by the database, the number of casualties is surely higher." Kiernan and Owen later revised their estimate of 2.7 million tons of U.S. bombs dropped on Cambodia down to the previously accepted figure of roughly 500,000 tons: See Kiernan, Ben; Owen, Taylor (2015-04-26). "Making More Enemies than We Kill? Calculating U.S. Bomb Tonnages Dropped on Laos and Cambodia, and Weighing Their Implications". The Asia–Pacific Journal. Retrieved 2017-07-18.

- ^ New York Times "Hue Massacre of 1968 Goes Beyond Hearsay" September 22, 1987

- ^ Time magazine "THE MASSACRE OF HUE" Oct. 31, 1969

- ^ Agent orange victims day, Tuoitre news 2013/08/11

- ^ History.com Operation Ranch Hand and Agent Orange Retrieved 25/09/12

- ^ "Defoliation" entry in Tucker, Spencer C., ed. (2011). The Encyclopedia of the Vietnam War (2nd ed.). ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-85109-961-0.

- ^ a b Bellamy, Alex J. (2017-09-29). East Asia's Other Miracle: Explaining the Decline of Mass Atrocities. Oxford University Press. pp. 33–34. ISBN 9780191083785.

- ^ "Body Count in Vietnam | HistoryNet". www.historynet.com. Retrieved 2018-06-04.

- ^ "Body Count in Vietnam | HistoryNet". www.historynet.com. Retrieved 2018-06-03.

- ^ http://ls-tlss.ucl.ac.uk/course-materials/POLS6016_65225

- ^ a b c Appy, Christian (1993). Working-Class War: American Combat Soldiers and Vietnam. http://projectsmrj.pbworks.com/f/Working+Class+War+-+Christian+Appy.pdf: UNC Chapel Hill. p. 273.

{{cite book}}: External link in|location= - ^ https://thevietnamwar.info/free-fire-zone/

- ^ a b c "What if America 'Won' the Vietnam War?". whatifhub.com. whatifhub.{{|date=April 2019|bot=medic}}

- ^ "'Anything That Moves': Civilians And The Vietnam War". www.wbur.org. Retrieved 2018-06-03.

- ^ Greiner, Bernd (2010). War Without Fronts: The USA in Vietnam. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0300168044.

- ^ a b Turse 2013, p. 251.

- ^ Turse 2013, p. 212.

- ^ Kim Chang-seok (2000-11-15). 편견인가, 꿰뚫어 본 것인가 미군 정치고문 제임스 맥의 보고서 "쿠앙남성 주둔 한국군은 무능·부패·잔혹". Hankyoreh (in Korean). Retrieved 2012-10-14.

- ^ Armstrong, Charles (2001). "America's Korea, Korea's Vietnam". Critical Asian Studies. 33 (4). Routledge: 530. doi:10.1080/146727101760107415.

- ^ "On War extra – Vietnam's massacre survivors". Al Jazeera. 2009-01-04. Retrieved 2012-10-14.

- ^ Go Gyeong-tae (2001-04-24). 특집 "그날의 주검을 어찌 잊으랴" 베트남전 종전 26돌, 퐁니·퐁넛촌의 참화를 전하는 사진을 들고 현장에 가다. Hankyoreh (in Korean). Retrieved 2012-10-14.

- ^ 여기 한 충격적인 보고서가 있다 미국이 기록한 한국군의 베트남 학살 보고서 발견. Ohmynews (in Korean). 2000-11-14. Retrieved 2012-10-14.

- ^ Kwon, Heonik (2006-11-10). After the massacre: commemoration and consolation in Ha My and My Lai. University of California Press. p. 2. ISBN 9780520247970.

- ^ Chomsky, Noam; Herman, Edward S. (1973). Counter-Revolutionary Violence:Bloodbaths in fact and propaganda (PDF). Warner Modular Publications.

- ^ Journal, The Asia Pacific. "Anatomy of US and South Korean Massacres in the Vietnamese Year of the Monkey, 1968 | The Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus". apjjf.org. Retrieved 2018-05-12.

- ^ a b https://www.nytimes.com/1970/01/10/archives/vietnam-killings-laid-to-koreans-researcher-says-he-found-evidence.html

- ^ a b CNN, James Griffiths. "The 'forgotten' My Lai: South Korea's Vietnam War massacres". CNN. Retrieved 2018-05-27.

{{cite news}}:|last=has generic name (help) - ^ "Citizens' court to investigate Vietnam War atrocities committed by South Korean troops". Retrieved 2018-06-03.

- ^ Clarke, Jeffrey J. (1988), United States Army in Vietnam: Advice and Support: The Final Years, 1965–1973, Washington, D.C: Center of Military History, United States Army, p. 275

- ^ Clarke, Jeffrey J. (1988), United States Army in Vietnam: Advice and Support: The Final Years, 1965–1973, Washington, D.C: Center of Military History, United States Army, p. 275

- ^ a b c Chuyên đề 4 CÔNG TÁC TÌM KIẾM, QUY TẬP HÀI CỐT LIỆT SĨ TỪ NAY ĐẾN NĂM 2020 VÀ NHỮNG NĂM TIẾP THEO, datafile.chinhsachquandoi.gov.vn/Quản%20lý%20chỉ%20đạo/Chuyên%20đề%204.doc

- ^ Joseph Babcock (26 April 2019). "Lost Souls: The Search for Vietnam's 300,000 or More MIAs". The Daily Beast. Retrieved 7 May 2019.

- ^ Whitcomb, Col Darrel (Summer 2003). "Victory in Vietnam: The Official History of the People's Army of Vietnam, 1954–1975 (book review)". Air & Space Power Journal. Archived from the original on 2009-02-07.

- ^ Marilyn Young. "The Vietnam Wars." Harper Perennial; September 1991. Chapter 14: "The “cease-fire war” claimed 26,500 ARVN dead in 1973, and almost 30,000 in 1974. Pentagon statistics listed 39,000 and 61,000 PRG/DRV dead for the same time period."

- ^ Shelby L. Stanton, 'The Rise and Fall of an American Army,' Spa Books, 1989, xvi.

- ^ Rummel 1997, Line 102.

- ^ Woodruff, Mark (1999). Unheralded Victory: Who won the Vietnam war?. Harper Collins. p. 211. ISBN 978-0004725192.

- ^ McCoy, Alfred W. (2006). A question of torture: CIA interrogation, from the Cold War to the War on Terror. Macmillan. p. 68. ISBN 978-0-8050-8041-4.

- ^ Harbury, Jennifer (2005). Truth, torture, and the American way: the history and consequences of U.S. involvement in torture. Beacon Press. p. 97. ISBN 978-0-8070-0307-7.

- ^ Appy, Christian G. (2000). Working-Class War: American Combat Soldiers and Vietnam. Univ of North Carolina Press. p. 153–156.

- ^ 3 new names added to Vietnam Veterans Memorial wall

- ^ US Military Operations: Casualty Breakdown

- ^ "Vietnam-era unaccounted for statistical report" (PDF). 26 July 2019.

- ^ a b Vietnam War Statistics

- ^ [1] [2]

- ^ American Vietnam War Casualty Statistics

- ^ Vietnam Prisoners of War – Escapes and Attempts

- ^ "Vietnam War U.S. Military Fatal Casualty Statistics".

- ^ https://www.uswings.com/about-us-wings/vietnam-war-facts/.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Scott McGaugh (16 September 2012). "Learning from America's Wars, Past and Present U.S. Battlefield Medicine Has Come a Long Way, from Antietam to Iraq". San Diego Union Tribune. Archived from the original on 27 July 2014. Retrieved 22 February 2013.

- ^ The American War Library. Vietnam War Casualties and Cause. Data compiled by William F. Abbott from figures obtained shortly after the construction of the Vietnam War Memorial.

- ^ a b Fighting on Two Fronts: African Americans and the Vietnam War; Westheider, James E.; New York University Press; 1997; pgs. 11–16

- ^ African-Americans In Combat

- ^ a b c War within war; The Guardian; September 14, 2001; James Maycock

- ^ Working-Class War: American Combat Soldiers & Vietnam; Appy, Christian; University of North Carolina Press; 2003; pgs. 31–33

- ^ Vietnam: The Soldier's Revolt

- ^ a b Working-Class War: American Combat Soldiers and Vietnam: American Combat

- ^ "Vietnam War Bomb Explodes Killing Four Children". Huffington Post. 3 December 2012.

- ^ Vietnam war shell explodes, kills two fishermen The Australian (April 28, 2011)

- ^ "Vietnam War Bombs Still Killing People 40 Years Later". The Huffington Post. 2013-08-14.

- ^ Ben Stocking for AP, published in the Seattle Times May 22, 2010 [seattletimes.com/html/health/2011928849_apasvietnamusagentorange.html Vietnam, US still in conflict over Agent Orange]

- ^ Jessica King (2012-08-10). "U.S. in first effort to clean up Agent Orange in Vietnam". CNN. Retrieved 2012-08-11.

- ^ "U.S. starts its first Agent Orange cleanup in Vietnam". Reuters. August 9, 2012.

- ^ Heuveline, Patrick (2001). "The Demographic Analysis of Mortality Crises: The Case of Cambodia, 1970–1979". Forced Migration and Mortality. National Academies Press. pp. 103–104. ISBN 9780309073349.

Subsequent reevaluations of the demographic data situated the death toll for the [civil war] in the order of 300,000 or less.

- ^ Banister, Judith; Johnson, E. Paige (1993). "After the Nightmare: The Population of Cambodia". Genocide and Democracy in Cambodia: The Khmer Rouge, the United Nations and the International Community. Yale University Southeast Asia Studies. p. 87. ISBN 9780938692492.

An estimated 275,000 excess deaths. We have modeled the highest mortality that we can justify for the early 1970s.

- ^ Sliwinski, Marek (1995). Le Génocide Khmer Rouge: Une Analyse Démographique. Paris: L'Harmattan. pp. 42–43, 48. ISBN 978-2-738-43525-5. Of 310,000 estimated Cambodian Civil War deaths, Sliwinski attributes 46.3% to firearms, 31.7% to assassinations (a tactic primarily used by the Khmer Rouge), 17.1% to (mainly U.S.) bombing, and 4.9% to accidents.

- ^ a b KOREA military army official statistics, AUG 28, 2005 Archived 2011-07-22 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b "Vietnam War, 1962–72 – Statistics". Australian War Memorial. 2003. Retrieved 2008-02-04.

- ^ "Australian servicemen listed as missing in action in Vietnam". Australian War Memorial. Retrieved 14 February 2015.

- ^ The Encyclopedia of the Vietnam War: A Political, Social, and Military History By Spencer C. Tucker "https://books.google.com/books?id=qh5lffww-KsC&lpg=PA53&dq=the%20encyclopedia%20of%20the%20vietnam%20war%20page%2064&pg=PA176&output=embed"

- ^ "New Zealand Rolls Of Honour – By Conflict". Freepages.genealogy.rootsweb.ancestry.com. Retrieved 2012-09-25.

- ^ "Overview of the war in Vietnam | VietnamWar.govt.nz, New Zealand and the Vietnam War". Vietnamwar.govt.nz. 1965-07-16. Archived from the original on 2013-07-26. Retrieved 2012-09-25.

- ^ a b Asian Allies in Viet-Nam

- ^ Womack, Brantly (2006). China and Vietnam: The Politics of Asymmetry. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521618342.

- ^ James F. Dunnigan; Albert A. Nofi (2000). Dirty Little Secrets of the Vietnam War: Military Information You're Not Supposed to Know. Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-312-25282-3.

External links

- National Archives AAD Searchable database.

- The Vietnam Center and Archive. Texas Tech University.

- Vietnamese Casualties During the American war