Washington Highlands (Washington, D.C.)

Washington Highlands | |

|---|---|

Washington Highlands, highlighted in red | |

| Population (2007) | |

• Total | 8,829 |

Washington Highlands is a residential neighborhood in Southeast Washington, D.C., in the United States. It lies within Ward 8, and is one of the poorest and most crime-ridden sections of the city. Most residents live in large public and low-income apartment complexes, although there are extensive tracts of single-family detached homes in the neighborhood.

Development of Washington Highlands

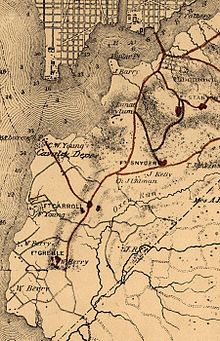

Washington Highlands is bounded by 13th Street SE on the northeast, Oxon Run Park on the northwest and southwest, and Southern Avenue on the southeast.[1] The neighborhood is situated on a series of high hills overlooking the creek known as Oxon Run.[2] It draws its name from the city of Washington, D.C., and the hills on which it was built.

At the time of European colonization of North America, the area known as Washington Highlands was occupied by Nacotchtank tribe of Native Americans, a non-migratory band whose villages lined the northern and southern banks of the Anacostia River.[3] The Nacochtanks were decimated by disease brought to the New World by European explorers, and disappeared by 1700 AD. The flat area below the highlands became farms owned by white settlers, with large numbers of African American slaves working the fields.[4]

The development of Washington Highlands closely parallels that of the adjacent neighborhood of Congress Heights.[4] In 1890, Colonel Arthur E. Randle,[a][5] a successful newspaper publisher, decided to found a settlement east of the river which he called Congress Heights.[6] The Pennsylvania Avenue Bridge (now the John Philip Sousa Bridge) began construction in November 1887,[7] and by June 1890 was nearing completion.[8] Randle understood that this new bridge would bring rapid development east of the Anacostia River, and he intended to take advantage of it.

The development was immediately successful.[9] To ensure that his investment continued to pay off, Randle invested heavily in the Belt Railway, a local streetcar company founded in March 1875.[9] On March 2, 1895, Randle founded the Capital Railway Company to construct streetcar lines over the Navy Yard Bridge and down Nichols Avenue to Congress Heights.[9][10]

Developers began laying out Washington Highlands in 1904,[11] and by August 1905 most of the subdivision's roads and tracts had been laid out.[12] Hungerford's addition was added to the neighborhood in 1906.[13] Fourth Street SE was opened in 1910 after a three-year effort,[14] although growth slowed for the next few years. By 1925, however, there were enough residents in the neighborhood to form a Washington Highlands Citizen Association.[15]

The city denied a 1927 request of citizens in the area for sewer lines to be built in their neighborhood.[16] There were too few residents in the area to justify the expense. But despite the effects of the Great Depression, development in the Washington Highlands area continued. In 1936 and 1937, more than 200 homes were built in the neighborhood, and in 1938 the city connected the area to the sewer system via the large Oxon Run sewer main.[17] The sewer system brought even more substantial growth. Another 250 homes were built in the neighborhood in 1938, and 100 more were planned. Even so, large parts of Washington Highlands remained undeveloped: Many streets existed only on paper, and the southern end of the area was primarily still farmland.[18]

World War II brought significant changes Washington Highlands. The war brought hundreds of thousands of defense workers into the city, creating a severe housing shortage. Congress created the National Capital Housing Authority (NCHA) to build extensive low-income housing throughout the region to alleviate the shortage. In 1942, the NCHA built the 256-unit Highland Dwellings.[19] In the fall of 1943, the NCHA approved a plan to build more than 300 low-income homes in Washington Heights, and private developers agreed to build another 150. Washington Highland residents were angry that their neighborhood was being turned into a low-income area, but the NCHA pushed the plan through.[20] The low-income housing boom continued in the area in the post-war period, with hundreds more homes being built. The post-war baby boom led to a significant increase in children in the area. After years of city inaction on recreational facilities in the neighborhood, the Washington Highlands Citizens Association successfully petitioned the city to take over the United States Navy's Bald Eagle storage facility and turn it into a recreational center.[21]

Washington Highlands was one of the first areas of the District of Columbia where housing was desegregated. Until the 1950s, law as well as housing covenants created by developers excluded African Americans from many neighborhoods in the city. But in 1951, the NCHA announced it would not longer segregate its housing complexes in Washington Highlands, and opened them to black residents. It began implementing its policy in 1953 This sparked a strong backlash from whites in Washington Highlands, which at that time had almost no African American residents.[19][22]

Current demographics and housing patterns

As of 2007, Washington Highlands had a population of 8,829, including 3,242 households and a median household income of $28,885. Just over 81 percent of residents in Washington Highlands are renters, and 18.7 percent are home owners. Roughly 71 percent of households are families.[23]

Most of the neighborhood it is low-income and public housing apartment complexes, including the 204-unit Highland Dwellings public housing complex. The District of Columbia Housing Authority received 2009 stimulus funding, and allocated $11 million towards rehabilitation of Highland Dwellings.[24][25] Wheeler Creek is a 314-unit community developed with a 1997 HOPE VI grant which replaced two earlier housing complexes, Valley Green and Skytower. Wheeler Creek includes 48 low-income rental units, 100 senior apartments, 32 market-rate rental units, and 30 lease/purchase units. The remaining units are for purchase.[26]

In 1967, the 12-story, 291-unit Parkside Terrace Apartments at 3700 9th Street SE was constructed. The apartment building for moderate- and low-income families was financed with federal money, and built by a group of private investors led by Polinger Construction and Judge Marjorie Lawson (a civil rights advisor to President John F. Kennedy).[27] By the early 2000s, however, the building was in serious disrepair and plagued by drug dealers, thieves, gangs, and numerous assaults. In 2003, the United States Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) sold its interest in the building. It was purchased by two nonprofit organizations—Community Preservation and Development, and Crawford Edgewood Management (a housing management company founded by H.R. Crawford, an African American former HUD official). The structure was gutted in 2005, leaving behind onlyt the interior columns, foundation, and a portion of the facade. The building reopened in 2009 as The Overlook. The building's lower seven floors (with 181 units) were set aside for low-income senior citizens. The building's top five floors (with 135 one- and two-bedroom units) were set aside for low- and moderate-income families. The Overlook features separate entrances and elevators for the senior citizen and family section, and each unit was wired for broadband Internet. The renovated building also featured several community rooms, a computer room, playground, controlled-access parking garage, and 3 acres (12,000 m2) of parkland. Retail space in the complex was occupied by a bank, convenience store, hair salon, and geriatric care center. Security at the building was very strong. Applicants for empty units could not have a criminal record of any kind, the building had an extensive security system, and security guards patrolled the interior.[28]

The largest apartment complex in the neighborhood is the 360-unit,[29] 700-resident Park South Apartments at 800 Southern Avenue SE.[30]

Park Southern Apartments

The Park Southern Apartments were built in 1965 as a public-private partnership, with funding coming from the city, the federal government, and a group of private investors led by Polinger Construction and Judge Lawson.[29][31] The goal of the block-long, hilltop development was to provide housing to individuals and families whose incomes were too high to qualify for federal housing subisidies but too low to afford market-rate rents in the city.[29]

The Park Southern was considered one of the best-run apartment complexes in the city until 1973. The Polinger company installed H.R. Crawford as resident manager. Strict in his enforcement of housing rules and selective in who he rented to, Crawford created a safe, well-landscaped, well-maintained apartment building which won national praise.[32][33] The Park Southern attained what The Washington Post called an "iconic" status for both helping very low-income people but maintaining a high standard of living.[30] Crawford left his post in March 1973 to take a position at HUD.[33]

The Park Southern Apartments declined after Crawford's departure, and suffered heavily from crime, vandalism, and other problems during the crack cocaine epidemic in the city in the 1980s and early 1990s. In 1995, two nonprofits, Jubilee Enterprise of Greater Washington and the Park Southern Neighborhood Corporation, purchsed the Park Southern from its original investors and began to renovate and refurbish the complex.[34] Jubilee Enterprise sold its interest in the complex to the Park Southern Neighborhood Corporation (PSNC) in 2001.[35] PSNC sought and won a $3 million loan from the city in May 2006 to make repairs at the property.[29]

PSNC's administration of the Park Southern Apartments has been strongly criticized. Several tenant lawsuits have alleged a broken HVAC system, cockroach and rodent infestations, a badly leaking plumbing system which has caused ceilings and walls to collapse, extensive mold and mildew throughout the complex, a security system which does not work, and damaged exterior access doors left hanging open.[29][30] The Washington Post reported in July 2014 that PSNC failed to make $628,262 in loan repayments to the city, owed more than $400,000 in unpaid utility and other bills, and that tens of thousands of dollars in tenant security deposits were missing.[29] In April 2014, D.C. housing officials seized the complex after PSNC defaulted on its loan.[29] City officials allege that PSNC has refused to turn over $300,000 in rent payments made in March 2014.[29] They further alleged that Rowena Joyce Scott, president of PSNC; Scott's daughter; and several PSNC board members illegally lived rent-free at Park Southern Apartments. The city began eviction proceedings against Scott, accusing her of owing more than $57,000 in back rent. (She contested the eviction.)[29] A subsequent investigation of the property showed such extensive problems that the city accused PSNC of "gross mismanagement".[30] D.C. housing officials say the Park Southern Apartments now need more than $20 million in repairs, which is almost as much as the building is worth.[29]

The Washington Post reported that PSNC attempted to sell the Park Southern Apartments to the former manager of the complex, Phinis Jones, in an attempt to pay back the city's loan. The newspaper said that this would "potentially [limit] further city oversight of the complex".[36] The D.C. housing authority, which had review authority over the transaction, vetoed the sale on July 11, 2014, although it did not rule out a sale to Jones at a future date.[36]

The troubles at the Park Southern Apartments roiled the November 2014 D.C. mayoral election. Scott, a long-time supporter of D.C. Mayor Vincent C. Gray, is a notable power-broker in local D.C. Democratic Party politics. According to article in The Washington Post, Scott secretly withdrew her support for Gray in early 2014 after the city began investigating tenant complaints at Park Southern Apartments, and switched her support to D.C. City Council member Muriel Bowser.[36] Scott then allegedly declined to mobilize residents of the Park Southern Apartments to vote for Gray at a January 17, 2014, Democratic Party "straw vote" held in city Ward 8 (where the apartment complex is located).[36] Gray subsequently lost the straw vote, and Bowser was catapulted to front-runner status in the Democratic mayoral primary.[37] Bowser then won the D.C. mayoral primary.[38] Scott subsequently accused Gray of targeting her and her nonprofit corporation in retaliation for the political activity.[30] The Washington Post reported on July 13, 2014 that Bowser had attempted to set up a private meeting between D.C. housing officials and PSNC (Gray ordered his officials to decline attendance); twice demanded to know under what legal authority city officials acted against PSNC; and challenged the city's right to seize PSNC's property under the terms of the loan default.[29] Michael Kelly, director of the District of Columbia Housing Authority, asked Bowser to schedule council hearings on PSNC's administration of the Park Southern Apartments, but Bowser (as of July 15) had declined to do so. Instead, Bowser asked the city's inspector general to open an investigation.[30] D.C. City Council member David Catania, an Independent candidate for mayor, accused Bowser of improperly intervening in the situation and engaging in ethically questionable conduct. Bowser dismissed Catania's criticism, and has alleged that problems at Park Southern Apartments are not as bad as the tenants and D.C. Housing Authority allege.[30]

On July 16, 2014, both the D.C. city's attorney general and the United States attorney for the District of Columbia announced civil and criminal investigations into PSNC's administration of the Park Southern Apartments.[29][39]

Landmarks

The most prominent landmark in Washington Highlands is Greater Southeast Community Hospital, the city-owned hospital that serves the majority of public healthcare needs in the District of Columbia.

Athletic facilities and parks

Washington Highlands is home to the Ferebee-Hope Recreation Center at 3999 8th Street SE. The center, which is surrounded by city-owned and maintained parkland, include an indoor, year-round gymnasium; outdoor basketball courts; and an aquatic center which provides year-round indoor swimming and aquatic activities. The Southeast Tennis and Learning Center at 701 Mississippi Avenue SE lies adjacent to Washington Highlands, just across Oxon Run Parkway.

The northeast end of Washington Highlands is dominated by Oxon Run Parkway, and the surrounding parkland. The southern border of this park, which is owned and maintained by the National Park Service, is 13th Street SE. City-owned undeveloped parkland, also known as Oxon Run Park, runs parallel to Valley Road SE and Livingston Road SE. Two athletic facilities occupy the segment of city-owned Oxon Run Park between 13th Street SE and Mississippi Avenue SE: the Wheeler and Mississippi park facility (benches and tables located at Wheeler Street SE and Mississippi Avenue SE) and the Oxon Run Park Outdoor Basketball Court 3 (at Valley Avenue SE and 13th Street SE). On the northern side of Oxon Run, just outside and adjacent to the Washington Highlands neighborhood, are the Oxon Run Park Amphitheater (opposite the Wheeler and Mississippi park facility) and Oxon Run Park Athletic Field 2 (also known as William O. Lockridge Field, opposite Oxon Run Park Outdoor Basketball Court 3 ). The next segment of city-owned Oxon Run Park, between Wheeler Road SE and 4th Street SE, contains three athletic facilities just north of Oxon Run (and technically outside the boundaries of but adjacent to Washington Highlands): the 4th and Mississippi park facility (4th Street SE and Mississippi Avenue SE), Oxon Run Park Athletic Field 1 (located at Simon Elementary School at 601 Mississippi Avenue SE), and the 4th and Wayne park facility (at 4th Street SE and Wayne Street SE). The lower segment of city-owned Oxon Run Park, between Atlantic Street SE and South Capitol Street, contains Oxon Run Park Outdoor Basketball Court 2 (at Atlantic Street SE and Livingston Road SE), Oxon Run Park Outdoor Basketball Court 1 (at Atlantic Street SE and Livingston Road SE), and the Livingston and Atlantic park facility (at Livingston Road SE and Atlantic Street SE).

The new ARC cultural arts center, and the Tennis and Learning Center, are located on Mississippi Avenue.

Public playgrounds

The Washington Highlands neighborhood has a single city-owned playground within its borders. This is the Oxon Run Park Playground #2, located at 4368 Livingston Road SE. A second city playground, the Ferebee-Hope Playground on the grounds of the Ferebee-Hope Recreation Center, is due to begin construction in the summer of 2015. New fences, handicapped-accessibility ramps, landscaping, lighting, and outdoor furniture are also scheduled for the recreation center.[40] Two other playgrounds exist within city-owned Oxon Run Park just north or west of Oxon Run itself. These include Oxon Run Park Playground #1 (Mississippi Avenue SE and 10th Place SE), and Oxon Run Park Playground #3 (4509 1st Street SE). A fourth playground, Oxon Run Playground-Play DC, is under construction at 501 Mississippi Avenue SE.

Libraries

Washington Highlands lacks a branch of the District of Columbia Public Library. The two closest libraries are Parklands-Turner Neighborhood Library at 1547 Alabama Avenue SE (near Alabama Avenue and Stanton Road SE) and the William O. Lockridge/Bellevue Neighborhood Library at 115 Atlantic Street SW (near Atlantic Avenue and South Capitol Street). The Parklands Library Kiosk, a metal-and-plastic "kiosk library" opened at Alabama Avenue and Stanton Road SE in 1977. It was replaced by the 1,500-square-foot (140 m2) Parklands-Turner Library (built across the street) in 1984.[41] In 2003, as work began on construction of the Henson Ridge Hope VI housing development, city officials announced they would close the kiosk library and build a new $1.5 million Parklands-Turner Library as part of the redevelopment of nearby Turner Elementary School.[42] But this plan fell through. In September 2009, Parklands-Turner Library closed for four weeks, and the old building demolished.[43] A new Parklands-Turner Library opened in The Shops at Parklands on Alabama Avenue in October 2009.[44] The Lockridge/Bellevue Neighborhood Library was formerly called the Washington Highlands Branch Library, but was never located in Washington Highlands. The library was demolished in 2009 and a new $15 million structure, designed by noted international architect David Adjaye, opened in September 2012. The branch was renamed Bellevue to better reflect the neighborhood in which the library exists. Although D.C. Board of Education member William O. Lockridge opposed the library's reconstruction, D.C. Mayor Vincent C. Gray successfully pushed to have the library renamed for him (even though a nearby athletic field already bore his name).[45]

Crime

Washington Highlands is among the most violent neighborhoods in the District of Columbia. Approximately one-third of the city's 181 homicides in 2007 occurred there.[46] The neighborhood became the focus of media attention in January 2008, when city officials discovered that Washington Highlands resident Banita Jacks had been living for months in her rowhouse with the bodies of her four murdered children in advanced states of decomposition upstairs.[47]

Notable residents

Former notable residents of Washington Highlands include the late Calvin and Wilhelmina Rolark, co-founders of the United Black Fund. Wilhelmina Rolark was a D.C. City Council member for 16 years.[48] Country music singer and performer Roy Clark who moved to the District of Columbia at the age of 11 and grew up on 1st Street SE.[49]

References

- ^ Randle, a graduate of the University of Pennsylvania, received the commission of colonel in the Mississippi State Militia from Andrew H. Longino, Governor of the state of Mississippi, in 1902.

- Citations

- ^ Smith 2010, p. 328.

- ^ Kyriakos, Marianne (March 13, 1999). "Washington Highlands: Working to Revitalize Area". The Washington Post. Retrieved July 11, 2010.

- ^ Smith 2010, p. 328s-329.

- ^ a b Smith 2010, p. 329.

- ^ "Col. Randle Kills Self in California". The Washington Post. July 5, 1929.

- ^ General Services Administration 2012, p. 4—27.

- ^ "It Was East End Day". The Washington Post. August 26, 1890.

- ^ "A Bridge Celebration". The Washington Post. June 3, 1890.

- ^ a b c Proctor, Black & Williams 1930, p. 732.

- ^ "Electric Railways". Municipal Journal & Public Works. February 26, 1908. p. 252.

- ^ "The Legal Record". The Washington Post. February 5, 1905. p. E5.

- ^ "Shows City's Growth". The Washington Post. August 18, 1905. p. 12.

- ^ "Increase in Volume of Surveyor's Work". The Washington Post. August 31, 1906. p. 10.

- ^ "Property Owners Protest". The Washington Post. January 13, 1907. p. 15; "Not to Widen Street". The Washington Post. February 18, 1910. p. 4.

- ^ "New Association Elects". The Washington Post. November 17, 1925. p. 22.

- ^ "Eastward Expansion of Capital Predicted". The Washington Post. September 16, 1927. p. 24.

- ^ Sadler, Christinetitle=Four-Lane Road Through Their Section to the District Line One of Objectives of Citizens Association (February 28, 1938). The Washington Post. p. X2.

{{cite news}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Sadler, Christinetitle=Area Grows Steadily Despite Handicap of Long Way to City (October 9, 1939). The Washington Post. p. 13.

{{cite news}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ a b "NCHA Racial Policy Meets Opposition". The Washington Post. April 28, 1953. p. 12.

- ^ "SE Citizens Protest New Housing Plan". The Washington Post. October 28, 1943. p. B1.

- ^ "Highlands Plan Own Recreational Facilities". The Washington Post. April 12, 1948. p. B1.

- ^ "Group Fights Opening Area to All Races". The Washington Post. May 9, 1953. p. 11.

- ^ Ward 8 Comprehensive Housing Analysis Washington, DC - Coalition for Nonprofit Housing & Economic Development

- ^ Samuelson, Ruth (2009-09-29). "DC Housing Authority Awarded $34.4 Million in Stimulus Funds". Washington City Paper. Retrieved 2010-07-12.

- ^ "Highland Dwellings Transformation" (PDF). East of the River. July 2010. Retrieved July 16, 2014.

- ^ Wheeler Creek Estates - National Housing Conference

- ^ "Mayor Breaks Ground for SE Project". The Washington Post. November 27, 1967. p. B2.

- ^ Alcindor, Yamiche (October 5, 2009). "D.C. Public Housing Unit Rises Again After Violent History". The Washington Post. Retrieved July 16, 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Davis, Aaron C. (July 13, 2014). "D.C. Housing Complex's Decline Raises Questions About Management, Politics". The Washington Post. Retrieved July 16, 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g Davis, Aaron C. (July 15, 2014). "Aiming to Quiet Critics, Muriel Bowser Requests Investigation of Park Southern". The Washington Post. Retrieved July 16, 2014.

- ^ "SE Housing Unit's Salary Qualification Listed in Its Ads". The Washington Post. January 24, 1966. p. B7.

- ^ Levy, Claudia (November 2, 1970). "SE's Model Manager: Secret of Success: Strict but Fair". The Washington Post. p. C1.

- ^ a b Levy, Claudia (April 7, 1973). "New HUD Official Remembers SE: H.R. Crawford Now Views It From Window in 'HUDville'". The Washington Post. p. E1.

- ^ Thompson, Tracy (May 29, 1996). "Community Revivals in Southeast". The Washington Post. p. B1.

- ^ "Park Southern Residents' Council v. Park Southern Neighborhood Corporation, Civil Action No. 2014 CA 002646 B, Civil Division, Superior Court of the District of Columbia". April 29, 2014. Retrieved July 16, 2014.

- ^ a b c d Davis, Aaron C. (July 14, 2014). "Gray Campaign Accuses Head of Park Southern Nonprofit of 'Double Dealing'". The Washington Post. Retrieved July 16, 2014.

- ^ DeBonis, Mike (January 18, 2014). "Bowser Beats Gray in D.C. Straw Poll of Ward 8 Democrats". The Washington Post. Retrieved July 16, 2014.

- ^ Nuckols, Ben (April 2, 2014). "Muriel Bowser Defeats Gray in DC Mayoral Primary". Associated Press. Retrieved July 16, 2014.

- ^ "Financial Dealings at Park Southern Apartment Complex Under Investigation". WRC-TV. July 16, 2014. Retrieved July 16, 2014.

- ^ Neibauer, Michael (April 22, 2015). "New multifamily on Pennsylvania Avenue SE, Umaya from Cafe Asia owner heads downtown". Washington Business Journal. Retrieved April 23, 2015.

- ^ "Parklands-Turner Community Library Opens Monday". The Washington Post. April 5, 1984. p. DC4.

- ^ Timberg, -Craig (July 31, 2003). "Different Reads on Library Plan". The Washington Post. p. T8.

- ^ "In Brief". The Washington Post. September 10, 2009. p. T2.

- ^ Craig, Tim (October 19, 2010). "Fenty Is Closing the Book on His Tenure As Mayor". The Washington Post. p. B1.

- ^ Stewart, Nikki (September 26, 2011). "D.C.'s Bellevue Library Faces Name Controversy". The Washington Post. Retrieved July 16, 2014; Kennicott, Philip (June 25, 2012). "District's New Pair of Libraries Are Exuberant Additions to Distressed Areas". The Washington Post. Retrieved July 16, 2014.

- ^ Karush, Sarah (January 11, 2008). "Mother Found With Decomposing Daughters". Brisbane Times. Retrieved July 16, 2014.

- ^ Klein, Allison; Alexander, Keith L.; Montes, Sue Anne Pressley (January 11, 2008). "SE Woman Says Four Daughters Were 'Possessed'". The Washington Post. Retrieved July 16, 2014.

- ^ Gates 2008, p. 677.

- ^ Clark & Eliot 1994, p. 84.

Bibliography

- Clark, Roy; Eliot, Marc (1994). My Life—In Spite of Myself!. New York: Pocket Books. ISBN 0671864343.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Gates, Henry Louis, ed. (2008). African American National Biography, Volume 8. Oxford, U.K.: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195160192.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - General Services Administration (2012). Department of Homeland Security Headquarters Consolidation at St. Elizabeths Master Plan Amendment, East Campus North Parcel: Environmental Impact Statement. Washington, D.C.: General Services Administration.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Proctor, John Clagett; Black, Frank P.; Williams, E. Melvin (1930). Washington, Past and Present: A History. New York: Lewis Historical Publishing Co.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Smith, Kathryn Schneider (2010). Washington At Home: An Illustrated History of Neighborhoods in the Nation's Capital. Baltimore, Md.: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 9780801893537.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Tindall, William (1918). "Beginnings of Street Railways in the National Capital". Records of the Columbia Historical Society, Washington, D.C: 24–86.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

Further reading

- Washington Highlands Target Area Investment Plan 2008 - DC Office of Planning

- HUD Secretary Donovan Cites Successful DC Area HOPE VI Models for Choice Neighborhoods Initiative

- Hoffer, Audrey (2007-09-01). "A Rebirth in Washington Highlands". The Washington Post. Retrieved 2010-07-11.