Al-Attarine Madrasa

| Madrasa al-Attarine | |

|---|---|

مدرسة العطارين | |

| |

| |

| General information | |

| Type | madrasa |

| Architectural style | Moorish |

| Location | Fes, Morocco |

| Coordinates | 34°03′54.3″N 4°58′25.3″W / 34.065083°N 4.973694°W |

| Construction started | 1323 CE |

| Completed | 1325 CE |

| Technical details | |

| Material | cedar wood, brick, stucco, tile |

| Floor count | 2 |

The Al-Attarine Madrasa or Medersa al-Attarine[1] (Arabic: مدرسة العطارين, romanized: madrasat al-ʿattārīn, lit. 'school of the perfumers') is a madrasa in Fes, Morocco, near the Al-Qarawiyyin Mosque. It was built by the Marinid sultan Uthman II Abu Said (r. 1310-1331) in 1323-5. The madrasa takes its name from the Souk al-Attarine, the spice and perfume market. It is considered one of the highest achievements of Marinid architecture due to its rich and harmonious decoration and its efficient use of limited space.[2][3][4][5]

History

[edit]

Context: Marinid madrasas

[edit]The Marinids were prolific builders of madrasas, a type of institution which originated in northeastern Iran by the early 11th century and was progressively adopted further west.[4] These establishments served to train Islamic scholars, particularly in Islamic law and jurisprudence (fiqh). The madrasa in the Sunni world was generally antithetical to more "heterodox" religious doctrines, including the doctrine espoused by the Almohad dynasty. As such, it only came to flourish in Morocco under the Marinid dynasty which succeeded the Almohads.[4] To the Marinids, madrasas played a part in bolstering the political legitimacy of their dynasty. They used this patronage to encourage the loyalty of Fes's influential but fiercely independent religious elites and also to portray themselves to the general population as protectors and promoters of orthodox Sunni Islam.[4][3] The madrasas also served to train the scholars and elites who operated their state's bureaucracy.[3]

The al-Attarine Madrasa, along with other nearby madrasas like the Saffarin and the Mesbahiyya, was built in close proximity to the al-Qarawiyyin Mosque/University, the main center of learning in Fes and historically the most important intellectual center of Morocco.[6][7][8] The madrasas played a supporting role to the Qarawiyyin; unlike the mosque, they provided accommodations for students, particularly those coming from outside of Fes.[9] Many of these students were poor, seeking sufficient education to gain a higher position in their home towns, and the madrasas provided them with basic necessities such as lodging and bread.[8][7] However, the madrasas were also teaching institutions in their own right and offered their own courses, with some Islamic scholars making their reputation by teaching at certain madrasas.[7]

Construction and operation of the madrasa

[edit]

The al-Attarine madrasa was built between 1323 and 1325 on the orders of the Marinid sultan Abu Sa'id Uthman II.[8][10][2] The supervisor of construction was Sheikh Beni Abu Muhammad Abdallah ibn Qasim al-Mizwar.[7][3] According to the Rawd el-Qirtas (historical chronicle), the sultan personally observed the laying of the madrasa's foundations, in the company of local ulema.[7]

The creation of the madrasa, as with all Islamic religious and charitable institutions of the time, required the endowment of a habous, a charitable trust usually consisting of mortmain properties, which provided revenues to sustain the madrasa's operations and upkeep, set up on the sultan's directive.[7] This provided for the madrasa to host an imam, muezzins, teachers, and accommodations for 50-60 students.[7][9][8] Most of the students at this particular madrasa were from towns and cities in northwestern Morocco such as Tangier, Larache, and Ksar el-Kebir.[9][8]

The madrasa has been classified as historic heritage monument in Morocco since 1915.[11] The madrasa has since been restored many times, but in a manner consistent with its original architectural style.[9] Today it is open as a historic site and tourist attraction.[12]

Architecture

[edit]Layout

[edit]The madrasa is a two-story building accessed via an L-shaped bent entrance at the eastern end of Tala'a Kebira street.[2][4] The vestibule leads to the main courtyard of the building, entered via an archway with a wooden screen (mashrabiya).[13] The south and north sides of the courtyard are occupied by galleries with two square pillars and two smaller marble columns, which support three carved wood arches in the middle and two smaller stucco muqarnas arches on the sides.[4][2] Above these galleries are the facades of the second floor marked by windows looking into the courtyard. This second floor, accessed via a staircase off the southern side of the entrance vestibule, is occupied by 30 rooms which served as sleeping quarters for the students.[13][4] This makes for an overall arrangement similar to the slightly earlier Madrasa as-Sahrij.[4] The entrance vestibule also grants access to a mida'a (ablutions hall) which is located at its northern side.[4][2]

At the courtyard's eastern end is another decorated archway which grants entrance to the prayer hall. Most of the Marinid-era madrasas were oriented so that the main axis of the building was already aligned with the qibla (the direction of prayer), allowing the mihrab (niche symbolizing the qibla) of the prayer hall to be allowed with the entrance of the main courtyard.[4] However, the space into which the al-Attarine Madrasa was built evidently did not allow for this layout, and instead the mihrab is off to the side on the southern wall of the prayer hall, on an axis perpendicular to the main axis of the building.[4] The prayer hall itself is rectangular, but a triple-arched gallery on its north side allowed architects to place a square wooden cupola over the main space in front of the mihrab.[4] This unusual but elegant solution to the limited and awkward space available for construction demonstrates the ingenuity and rational approach to design that Marinid architects had achieved by this time.[2]: 313 [3]

-

Wooden roof and stucco decoration over the street in front of the madrasa's entrance

-

Wooden mashrabiya screen at the entrance of the courtyard

-

Western side of the courtyard, looking towards the entrance

-

One of the galleries along the sides of the courtyard

-

Eastern side of the courtyard, looking towards the entrance of the prayer hall

-

The prayer hall and mihrab

-

The former ablutions facility (mida'a)

-

The upper floors of the madrasa, where the student sleeping quarters are located

Decoration

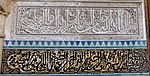

[edit]Although its exterior is completely plain (like most traditional Moroccan buildings of its kind), the madrasa is famous for its extensive and sophisticated interior decoration, which exhibits a rigorous balance between different elements, marking the period of highest achievement in Marinid architecture.[4][3][2]: 347, 360 The main courtyard demonstrates this in particular. The floor pavement and the lower walls and pillars are covered in zellij (mosaic tilework). While most of the zellij is arranged to form geometric patterns and other motifs, its top layer, near eye-level, features a band of calligraphic inscriptions on sgraffito-style tiles running around the courtyard.[2][14] Above this, in general, is a zone of extensive and intricately-carved stucco decoration, including another layer of calligraphic decoration, niches and arches sculpted with muqarnas, and large surfaces covered in a diverse array of arabesques (floral and vegetal patterns) and other Moroccan motifs.[2][3][5] Lastly, the upper zones generally feature surfaces of carved cedar wood, culminating in richly sculpted wooden eaves projecting over the top of the walls. Wooden artwork is also present in the pyramidal wooden cupola ceiling of the prayer hall, carved with geometric star patterns (similar to that found more broadly in Moorish architecture). The wood-carving on display here is also considered an example of the high point of Marinid artwork.[4]: 337

The prayer hall also features extensive stucco decoration, especially around the richly-decorated mihrab niche.[13][4] The entrance of the hall consists of a "lambrequin"-style arch whose intrados are carved with muqarnas. The upper walls of the chamber, below the wooden cupola, also feature windows of coloured glass which are set into lead grilles (instead of the much more common stucco grilles of that period) forming intricate geometric or floral motifs.[13][4]: 338 The marble (or onyx) columns and the engaged columns of the courtyard and prayer hall also feature exceptionally elegant and richly-carved capitals, among the best examples of their kind in this period.[13][4]: 340

The madrasa also features notable examples of Marinid-era ornamental metalwork. The doors of the madrasa's entrance are made of cedar wood but are covered in decorative bronze plating. The current doors in place today are replicas of the originals which are now kept at the Dar Batha Museum.[3] The plating is composed of many pieces assembled together to form an interlacing geometric pattern similar to that found in other medieval Moroccan art forms such as Qur'anic or manuscript decoration.[3] Each piece is chiseled with a background of arabesque or vegetal motifs, as well as a small Kufic script composition inside each of the octagonal stars in the wider geometric pattern. This design marks an evolution and refinement of the earlier Almoravid-era bronze-plated decoration on the doors of the nearby Qarawiyyin Mosque.[3] Another piece of notable metalwork in the madrasa is the original bronze chandelier hanging in the prayer hall, which includes an inscription praising the madrasa's founder.[3][13]

-

Example of zellij tilework in the madrasa, with complex geometric patterns on the lower walls and a band of calligraphy above

-

View of the small arches and blind arches (or niches) at the corners of the courtyard which are sculpted with muqarnas

-

Example of motifs in carved stucco around the courtyard

-

Details of the wood-carving along the top of the walls in the courtyard

-

Wooden cupola ceiling in the prayer hall

-

The "lambrequin" or muqarnas arch of the prayer hall's entrance

-

Details of the stucco decoration (and a marble engaged column) around the mihrab

-

Stucco decoration and coloured glass windows in the upper walls of the prayer hall

-

The decorative bronze plating of the doors at the madrasa's entrance (replicas of the originals)

-

The Marinid-era bronze chandelier in the prayer hall

References

[edit]- ^ "Madrasa al-'Attarin". Archnet. Retrieved 2020-04-16.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Kubisch, Natascha (2011). "Maghreb - Architecture". In Hattstein, Markus; Delius, Peter (eds.). Islam: Art and Architecture. h.f.ullmann. pp. 312–313.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Lintz, Yannick; Déléry, Claire; Tuil Leonetti, Bulle (2014). Maroc médiéval: Un empire de l'Afrique à l'Espagne. Paris: Louvre éditions. p. 486. ISBN 9782350314907.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Marçais, Georges (1954). L'architecture musulmane d'Occident. Paris: Arts et métiers graphiques. pp. 288–289.

- ^ a b Bloom, Jonathan M. (2020). Architecture of the Islamic West: North Africa and the Iberian Peninsula, 700-1800. Yale University Press. p. 191.

- ^ Métalsi, Mohamed (2003). Fès: La ville essentielle. Paris: ACR Édition Internationale. ISBN 978-2867701528.

- ^ a b c d e f g Gaudio, Attilio (1982). Fès: Joyau de la civilisation islamique. Paris: Les Presse de l'UNESCO: Nouvelles Éditions Latines. ISBN 2723301591.

- ^ a b c d e Le Tourneau, Roger (1949). Fès avant le protectorat: étude économique et sociale d'une ville de l'occident musulman. Casablanca: Société Marocaine de Librairie et d'Édition.

- ^ a b c d Parker, Richard (1981). A practical guide to Islamic Monuments in Morocco. Charlottesville, VA: The Baraka Press.

- ^ Lintz, Yannick; Déléry, Claire; Tuil Leonetti, Bulle (2014). Maroc médiéval: Un empire de l'Afrique à l'Espagne. Paris: Louvre éditions. p. 486. ISBN 9782350314907.

- ^ "Medersa El-Attarine". Inventaire et Documentation du Patrimoine Culturel du Maroc (in French). Retrieved 2021-01-08.

- ^ "Medersa El Attarine | Fez, Morocco Attractions". Lonely Planet. Retrieved 2020-04-16.

- ^ a b c d e f Touri, Abdelaziz; Benaboud, Mhammad; Boujibar El-Khatib, Naïma; Lakhdar, Kamal; Mezzine, Mohamed (2010). Le Maroc andalou : à la découverte d'un art de vivre (2 ed.). Ministère des Affaires Culturelles du Royaume du Maroc & Museum With No Frontiers. ISBN 978-3902782311.

- ^ Degeorge, Gérard; Porter, Yves (2001). The Art of the Islamic Tile. Translated by Radzinowicz, David. Flammarion. pp. 66–68. ISBN 208010876X.

External links

[edit]- 'Attarin Madrasa at Museum with no Frontiers

- Attarine Madrasa فاس - مدرسة العطارين - Photos from the Manar al-Athar Digital Photo archive