Harriet Powers

Harriet Powers | |

|---|---|

Photograph of Harriet Powers (1901) | |

| Born | Harriet Powers October 29, 1837 |

| Died | January 1, 1910 (aged 72) |

| Nationality | American |

| Known for | Quilting |

| Notable work | Bible Quilt 1886 Pictorial Quilt 1898 |

Harriet Powers (October 29, 1837 – January 1, 1910)[1] was an American folk artist and quilter born into slavery in rural northeast Georgia. Powers used traditional appliqué techniques to make quilts that expressed local legends, Bible stories, and astronomical events. Powers married young and had a large family. After the American Civil War and emancipation, she and her husband became landowners by the 1880s, but lost their land due to financial problems.

Only two of her quilts are known to have survived: Bible Quilt 1886 and Pictorial Quilt 1898. Her quilts are considered among the finest examples of nineteenth-century Southern quilting.[2] Her work is on display at the National Museum of American History in Washington, D.C., and the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, Massachusetts

Biography

[edit]Powers was born into slavery in 1837 near Athens, Georgia. She is believed to have spent her early life on a plantation as a slave, owned by John and Nancy Lester in Madison County and learned to sew from other slaves or from her female enslaver.[3]

In 1855, at the age of eighteen, Powers married Armstead Powers.[3] They had at least nine children together.[4][5]

Following the American Civil War, the Powerses and their children were emancipated. On the 1870 census they were recorded as having $300 (~$7,228 in 2023) in personal property, although they did not own land. In terms of occupation, Powers was listed as 'keeping house' and her husband as a 'farmhand.' At this point, three of their children– Amanda, Leon Joe (Alonzo), and Nancy– still lived at home.[6][7]

By the 1880s Powers and her family owned four acres of land and ran a small farm in Clarke County.[7][8] In 1886, Powers exhibited her first quilt at the Athens Cotton Fair.[4][5][7] After some financial difficulty, Armstead began to slowly sell off tracts of land in the early 1890s, and he ultimately defaulted on his taxes.[7] Despite their financial troubles, the Powerses did not lose their home.[4] Their region had a cash poor, rural economy, and it was difficult for African Americans to collect the cash for taxes and fees.

In 1894, Armstead left Powers; she never remarried and likely supported herself as a seamstress.[3][7] She remained in Clarke County for most of her life.[9][7]

Although an 1895 Chicago Tribune article[10] about the Cotton States and International Expo described Powers as ignorant and illiterate, learning Bible stories from "others more fortunate", Powers was literate. Quilt historian Kyra E. Hicks discovered a letter written by Powers while conducting research for her book on the quilter: This I Accomplish: Harriet Powers' Bible Quilt and Other Pieces (2009).[11] The letter was a copy of an 1896 letter from Powers to a prominent woman from Keokuk, Iowa; it shared insights into Powers's life when she was enslaved, how and when she learned to read and write, and descriptions of at least four of her quilts.[12] Powers wrote that she learned Bible stories through her own study of the book.[12]

Powers died on January 1, 1910; and was buried in the Gospel Pilgrim Cemetery in Athens.[13] Her grave was rediscovered in January 2005.[14]

Career

[edit]Powers exhibited her first quilt, The Bible Quilt, in 1886 at the Athens Cotton Fair.[4][5] It was here that Jennie Smith, an artist and art teacher from the Lucy Cobb Institute, saw the quilt, which she found to be remarkable,[15] and asked to purchase it. Powers refused to sell, but the two women remained in touch. Four years later, Powers, met with financial difficulties and encouraged by her husband to sell,[16] offered to sell the quilt to Smith for ten dollars; Smith agreed but talked the price down to five dollars (~$170.00 in 2023).[5] Powers vividly explained the imagery on the quilt to Smith– who recorded these explanations, adding notes of her own, in her personal diary.[3] It may be that Smith elaborated on the Christian content in her account.[5] Powers visually communicated with her narrative quilts in themes from her own experience and the techniques from the age-old crafts of African Americans.[17]

Powers' second quilt, The Pictorial Quilt, was made in 1898 and its history is somewhat unclear. One account suggests that it was commissioned by the wives of faculty members of Atlanta University, who had seen the first quilt at the Cotton States Exhibition in Atlanta in 1895, when Powers and her husband had separated.[5] According to another source, the quilt was purchased in Nashville, Tennessee, in 1898.[citation needed]

Whatever its origins, the piece was presented to the Reverend Charles Cuthbert Hall of New York City, who was serving as the vice-chairman of the University's board of trustees at the time. The reverend's heirs sold the quilt to collector Maxim Karolik, who then donated it to the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.[18]

In an 1896 letter, Powers describes a quilt made in about 1882 that she called The Lord's Supper Quilt.[8] Similarly, records of other quilts exist but it's unclear if they or The Lord's Supper Quilt have survived.[5][8]

Works

[edit]Bible Quilt 1886

[edit]

Finished in 1886, The Bible Quilt (measuring 88 in × 73+3⁄4 in, 2,240 mm × 1,870 mm) is constructed out of cotton cloth and arranged in three rows with a total of 11 panels, or squares.[8][19] Some scenes are given larger panels than others. The quilt has a 'random' quality although the scenes are arranged linearly.[19] The Bible Quilt was made using appliqué techniques, and was both hand and machine sewn.[4][19]

The panels depict Bible stories, such as Jacob and his ladder, portrayed in the spiritual "We Are Climbing Jacob's Ladder." This Old Testament account was popular with slaves since they related to the hunted, homeless Jacob and the ladder, which they interpreted as representing escape from slavery.[3] Other subjects are Adam and Eve, Eve and her son in a continuance of Paradise, Satan among the seven stars, Cain killing Abel, Cain going into the Land of Nod for a wife, Job, Jonah and the Whale,[5] the Baptism of Christ, the Crucifixion, Judas Iscariot and the thirty pieces of silver, the Last Supper, the Holy Family, and Christ's ascension to Heaven.[5] Powers, a second or third generation enslaved woman, may have chosen these stories as coded messages of loss and escape.[5]

Jennie Smith, a young local artist who had studied abroad, saw the quilt at the Athens Cotton Fair of 1886. She later wrote that she was taken with the quilt because, "[Powers's] style is bold and rather on the impressionist's order while there is a naivete of expression that is delicious."[20] She offered to buy it then, but Powers did not want to sell. Four years later Powers returned to Smith, offering to sell the quilt because of her family's needs. She explained the panels to Smith at the time, who recorded her comments. Powers visited the quilt on several occasions while Smith owned it, demonstrating its special significance in her life.[20]

Provenance

[edit]The Bible Quilt was gifted to the Smithsonian Institution by Mr and Mrs. H M. Heckman. It is currently on display at the National Museum of American History.[4]

Bible Quilt controversy

[edit]In 1992 The Smithsonian Institution hired a Chinese company to make reproductions of Bible Quilt, along with several other noted 19th-century quilts, including Susan Strong's 1830 Great Seal Quilt.[21][22] These plans for foreign reproductions and sales raised great controversy.

When the first reproductions appeared in Spiegel catalogue for purchase, many Americans were shocked.[citation needed] The quilting and arts community, particularly The National Quilting Association [23] and Maryland's Four County Quilt Guild,[24] were extremely upset by these reproduction efforts.[citation needed]

They believed that it was disrespectful to make money off the Bible Quilt and other similar works without exploring who might own the familial rights to the work and who could receive some of the royalties from its reproduction. The quilting and arts community were also concerned that the mass reproduction of these unique, timeless quilts would not only dampen the significance of their makers, but obscure the important origins of their place in American history. These groups believed strongly that, if reproductions were going to be made, they should be produced by American quilting companies to help support the craft in the U.S.

Many felt so passionately about this cause that they canceled their Smithsonian memberships, contacted their congressmen, signed petitions, and protested on the National Mall in Washington, D.C.[citation needed] Based on these responses, the Smithsonian Institution made several changes to their reproduction project. They had "Copyright 1992 Smithsonian Institution"[25] printed on every quilt to avoid confusion. They agreed to prohibit sale of quilt reproductions in museum gift shops or any type of catalogue, and contracted for quilt reproductions with two domestic companies, Cabin Creek Quilters in Appalachia and Missouri Breaks, a group based on the Lakota Sioux reservation.[26] To prevent such controversies in the future, the Smithsonian additionally began to hold public forums that fostered discussion and further research about ethical practices as related to artistic reproductions.[citation needed]

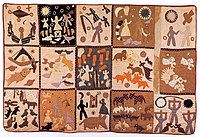

Pictorial Quilt 1898

[edit]

The Pictorial Quilt (measuring 68+7⁄8 in × 105 in, 1,750 mm × 2,670 mm), completed in 1889, is also constructed from cotton and made using appliqué techniques. There 15 equally sized panels, or squares, arranged in three rows of five. There are 10 biblical images, four historical scenes, and a morality lesson. The scenes are not arranged sequentially, but are randomly placed mixing both biblical and historical scenes.[18][19]

Of the 10 Bible stories depicted, three refer to God's creation of creatures in pairs (Panels 7, 9, and 14). Other stories include Adam and Eve and the serpent (Panel 4), Moses and the serpent (Panel 3), Jonah and the whale (Panel 6), Job praying for his enemies (Panel 1), the angels of wrath and the seven vials (Panel 10), and two scenes from the life of Jesus (Panels 5 and 15).[19]

The four historical panels depict natural phenomena that impressed Americans and became part of oral tradition, some of which occurred before Powers' birth. For example, Panel 2 which depicts The Dark Day of May 19, 1780, a day so dark the sun appeared to be blocked out (this was caused by smoke and ashes from forest fires in Canada); as well as, Panel 8 which represents the Leonid meteor shower of 1833. Panel 11 portrays 'Cold Thursday,' February 10, 1895. Here Powers portrays individuals frozen in their tracks. Panel 12 represents the Red Light Night of 1846.

Panel 13 is the morality lesson and depicts two rich people who were given everlasting punishment for knowing nothing of God. The panel also shows a hog said to have walked from Georgia to Virginia.[27][28][29][19]

Provenance

[edit]According to Cuthbert family history, Reverend Charles Cuthbert Hall was given the quilt in 1898 by a group of "faculty ladies" at Atlanta University. The Presbyterian minister had just been appointed as president of Union Seminary in New York. His son Reverend Basil Douglas Hall (1888 - 1979) inherited it about 1961.

Collectors Maxim and Martha Karolik purchased the work in 1964, donating it to the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, in a bequest. It is displayed there.[18]

Style

[edit]Bible Quilt 1886 and Pictorial Quilt 1898 depict biblical and historical scenes as well as celestial phenomena. Both quilts are hand and machine stitched, using appliqué and piecework techniques that demonstrate both African-American and African influences.[19] They are notable for their bold use of these techniques and storytelling.

Jennie Smith recorded Harriet Powers's comments for each square of the Pictorial Quilt.[citation needed] These comments were included in documentation when the quilt was given to Reverend Cuthbert of Atlanta University. According to her notes, for the Leonid or falling stars square, Powers said, "The people were frightened and thought that the end of time had come. God's hand staid the stars. The varmints rushed out of their beds."[30] Another panel illustrates the 'dark day' May 19, 1780 (now identified as a historically dense smoke over North America caused by Canadian Wildfires).[6]

Art historians have identified similarities between West African appliqué wall hangings and Powers's works. Similar to the appliquéd textiles of Benin, Powers's work feature standardized symbols with little variation. For example, most of the human figures, both male and female, in the Bible Quilt seem to be made from a singular pattern. Male figures are differentiated from female ones through a V-shape cut from the skirt. Additionally, her representations of humans, animals, and objects are minimalist and capture the essence of the figure, making her work stylistically similar to works made by the Fon, Asante, Fante, and Ewe.[19]

Author Floris Barnett Cash suggests that Powers's interest in celestial scenes, religious stories, and astronomical occurrences reflected interchanges within the Black community where she lived. Community-shared information, such as hearing sermons from preachers every Sunday, or the news, was shared during quilting frolics and was incorporated into her quilts.[17]

Other analysts have suggested that Powers' interest in celestial bodies was related to a belief in their religious significance,[31] or that they were related to a fraternal organization of some sort. Her interpretations of both quilts have survived in writings by others. The result may have been influenced by the people recording her comments. Researchers have learned that Powers was literate, but she might also have used her quilts as teaching tools, as many people in her community were likely unable to read.[citation needed]

Death, burial and memorial

[edit]Powers, "an aged Negro woman who held the esteem of many Athens people," according to her death notice in the Athens Banner, died January 1, 1910, of pneumonia and was buried at the local African American resting place, Gospel Pilgrim Cemetery in Athens.[32] In 2005, University of Georgia graduate student Cat Holmes rediscovered the joint headstone for Powers and her husband, Armsted, which over the years had been obscured by overgrown vegetation.[33] The marker held the couple's name and was about 24 in × 15 in × 3⁄4 in (610 mm × 381 mm × 19 mm) and "seems to have been erected by Powers' youngest son, Marshall", whose name was at the top of the headstone.[33] Holmes had been searching for the grave off and on for about two years. On Christmas Eve 2004, Holmes and her husband, David Berle, a University of Georgia horticulture professor, who had been assisting with restoration efforts for the cemetery, were searching in a "still uncleared" area.[33] First they found a marker for Viola Powers (a daughter-in-law) and then, an hour later, the Powers' headstone.[33]

In December 2023, a new, commemorative memorial for Harriet and Armstead Powers was dedicated at the Gospel Pilgrim Cemetery. The memorial was sponsored by the Women of Color Quilters Network.[34][35][36]

Posthumous honors

[edit]In 2009, Powers was inducted into the Georgia Women of Achievement Hall of Fame.[3]

In October 2010, organizations in Athens, Georgia, produced several events related to the theme "Hands That Can Do: A Centennial Celebration of Harriet Powers." The events included a quilt exhibit, storytelling, a gospel concert, a symposium, a commemorative church service at New Grove Baptist Church in Winterville, and visit to the Powers grave site.[37][38]

Athens-Clarke County Mayor Heidi Davison issued a proclamation naming October 30, 2010, as Harriet Powers Day.[citation needed]

In popular culture

[edit]Children's literature

[edit]- Fader, Ellen. (March 1, 1994). "Stitching Stars: The Story Quilts of Harriet Powers", The Horn Book Magazine. Vol. 70, no. 2, p. 219(2).

- Herkert, Barbara, and Vanessa Brantley-Newton (illustrator). Sewing Stories: Harriet Powers' Journey From Slave To Artist. New York: Knopf Books for Young Readers, 2015. OCLC 864752924

- Lyons, Mary E. Stitching Stars: The Story Quilts of Harriet Powers. New York, NY: Aladdin Paperbacks, 1997. OCLC 38176225

Quilt patterns

[edit]- Powers, Harriet. A Pattern Book: Based on an Appliqué Quilt by Mrs. Harriet Powers, American, 19th Century. Boston: Museum of Fine Arts, 1970. OCLC 6038345

- Perry, Regenia. Harriet Powers's Bible Quilts. New York: Rizzoli International, 1994. OCLC 29356836

- Hicks, Kyra E. The Lord's Supper Pattern Book: Imagining Harriet Powers' Lost Bible Story Quilt. Arlington: Black Threads Press, 2011. OCLC 779971630

Theater

[edit]- Cavalieri, Grace. Quilting the Sun. commissioned by the Smithsonian Institution and Visual Press of the University of Maryland, 2000.[39]

- First performed in New York City (2002) by the Xoregos Performing Company.

See also

[edit]- African-American art

- Baltimore album quilts

- History of quilting

- Quilting

- List of slaves

- The Quilts of Gee's Bend

References

[edit]- ^ Ashley Callahan. "Harriet Powers (1837–1910)". New Georgia Encyclopedia.

- ^ Harriet Powers Archived October 18, 2007, at the Wayback Machine, Early Women Masters.

- ^ a b c d e f "HARRIET POWERS – Nurse. Volunteer. social activist". Georgia Women of Achievement. March 2009. Archived from the original on December 21, 2019. Retrieved August 27, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f "1885 – 1886 Harriet Powers's Bible Quilt". National Museum of American History. Retrieved March 5, 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Hunter, Clare (2019). Threads of life : a history of the world through the eye of a needle. London: Sceptre (Hodder & Stoughton). pp. 201–203. ISBN 9781473687912. OCLC 1079199690.

- ^ a b Reed Miller, Rosemary E. (2002). Threads of Time, The Fabric of History. Washington, DC: T&S Press. p. 32. ISBN 0-9709713-0-3.

- ^ a b c d e f "Harriet Powers an artist of story quilts web". Retrieved March 22, 2018.

- ^ a b c d Johnson, Alyssa (February 8, 2019). "A Modern Mother: Harriet Powers". Africana Studies Student Research Conference.

- ^ "Biography of Harriet Powers". americanartgallery.org. Retrieved April 1, 2021.

- ^ "EXHIBIT OF THE NEGROES (November 24, 1895)". Retrieved March 5, 2016.

- ^ Hicks, Kyra E. (2009). This I Accomplish: Harriet Powers' Bible Quilt and Other Pieces (1St ed.). Place of publication not identified: Black Threads Press. ISBN 9780982479650.

- ^ a b Kyra E. Hicks, "This I Accomplish": Harriet Powers' Bible Quilt and Other Pieces, pp. 37–40.

- ^ Morris, Emmeline E. E. (2007). Gospel Pilgrim's Progress: Rehabilitating an African American Cemetery for the Public (master's thesis). University of Georgia. p. 71. Retrieved January 15, 2023.

- ^ Ulrich, Laurel Thatcher (2011). "'A Quilt Unlike Any Other': Rediscovering the Work of Harriet Powers". In Elizabeth Anne Payne (ed.). Writing Women's History: A Tribute to Anne Firor Scott. UP of Mississippi. pp. 82–116. ISBN 9781617031748. Retrieved November 12, 2014.

- ^ "Pictorial quilt". Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Retrieved March 5, 2016.

- ^ Miles, Tiya (2021). All That She Carried. Random House. pp. 37–39. ISBN 9781984854995.

- ^ a b Cash, Floris Barnett (1995). "Kinship and Quilting: An Examination of an African-American Tradition". The Journal of Negro History. 80 (1): 30–41. doi:10.2307/2717705. ISSN 0022-2992. JSTOR 2717705. S2CID 141226163.

- ^ a b c "Pictorial quilt". collections.mfa.org. Retrieved May 6, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Vlach, John Michael (1978). The Afro-American tradition in decorative arts. Cleveland Museum of Art. Cleveland: University of Georgia Press. ISBN 0-910386-39-0. OCLC 3608807.

- ^ a b "1885 – 1886 Harriet Powers's Bible Quilt". Smithsonian: National Museum of American History. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved October 26, 2016.

- ^ KONCIUS, JURA (April 10, 1992). "Smithsonian Wraps Itself in Controversy : Americana: The museum is authorizing the sale of foreign-made reproductions of classic American quilt designs". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ "1825 - 1840 Susan Strong's "Great Seal" Quilt". National Museum of American History.

- ^ "NQA - National Quilting Association". QuiltingHub.

- ^ "Maryland's Four County Quilt Guild". Archived from the original on February 6, 2019. Retrieved March 4, 2020.

- ^ "Smithsonian Wraps Itself in Controversy : Americana: The museum is authorizing the sale of foreign-made reproductions of classic American quilt designs". Los Angeles Times. April 10, 1992. Retrieved March 4, 2020.

- ^ "The Smithsonian Quilt Controversy | World Quilts: The American Story". worldquilts.quiltstudy.org.

- ^ Cole, Thomas B. (November 19, 2014). "Pictorial Quilt: Harriet Powers". JAMA. 312 (19): 1952–1953. doi:10.1001/jama.2013.279853. ISSN 0098-7484. PMID 25399258.

- ^ McCaskill, Barbara (2006). Encyclopedia of African-American culture and history : the Black experience in the Americas (2nd ed.). Detroit: Macmillan Reference USA. pp. 1830–1831. ISBN 0028658167. Retrieved October 26, 2016.

- ^ Cole, T. B. (2014). "Pictorial Quilt". Journal of the American Medical Association. 312 (19): 1952–1953. doi:10.1001/jama.2013.279853. PMID 25399258.

- ^ May, Rachael (2018). An American quilt. Unfolding a story of family and slavery. Pegasus Books. pp. 209 (quoted on). ISBN 978-1-68177-417-6. OCLC 1035751122.

- ^ Adams, Marie Jeanne (1976). "The Harriet Powers Pictorial Quilts". Black Art. 3: 12–28. ISSN 0145-8116. OCLC 2792353.

- ^ "Aged Colored Woman Dies in Athens". Athens Banner. January 4, 1910.

- ^ a b c d Shearer, Lee (January 9, 2005). "Famous grave found off Fourth Street: Digging through history; quilter remembered". Online Athens: Athens Banner-Herald.

- ^ Carroll, Nell (December 4, 2023). "PHOTOS: Revered quilter is honored in Athens". The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Retrieved January 5, 2024.

- ^ McCarthy, Rebecca (December 4, 2023). "More than 100 years after her death, a revered quilter is honored in Athens". The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Retrieved January 5, 2024.

- ^ Wood, Jesse (December 4, 2023). "Ceremony held to commemorate Armstead and Harriet Powers' new headstone". The Red and Black. Retrieved January 5, 2024.

- ^ " Stitch in Time," by Julie Philips, 'Athens Banner-Herald, October 24, 2010, [1]

- ^ "Stitch in Time: 'Hands that Can Do' A Centennial Celebration of Harriet Powers". Athens Banner-Herald (GA). October 24, 2010.

- ^ "Artworks Summer 2002". archive.wvculture.org. Retrieved December 7, 2022.

Further reading

[edit]- Adams, Monni. "Harriet Powers' Bible Quilts", The Clarion, Spring 1982, American Folk Art Museum.

- Bobo, Jacqueline. Black Feminist Cultural Criticism. Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2001. Print.

- Finch, Lucine, "A Sermon in Patchwork," Outlook, October 28, 1914, pp. 493–495. Published four years after Powers's death, Lucine Finch's article includes a photograph of the Bible Quilt, description of each quilt block, and (presumably) quotes by Powers.[1]

- Hicks, Kyra E. Black Threads: An African American Quilting Sourcebook, McFarland & Company, 2003. ISBN 0-7864-1374-3

- Hicks, Kyra E. This I Accomplish: Harriet Powers' Bible Quilt and Other Pieces, Black Threads Press, 2009. ISBN 978-0-9824796-5-0

- Holmes, Catherine L., "The darling offspring of her brain: the quilts of Harriett Powers" in Georgia Quilts: Piecing Together a History, University of Georgia Press, Athens, Georgia, 2006. ISBN 9780820328997

- Perry, Regenia A. (1972). Selections of nineteenth-century Afro-American art. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

- Jacquiline L. Tobin and Raymond G. Dobard, Hidden in Plain View: A Secret Story of Quilts and the Underground Railroad (Anchor Books, 2000).

External links

[edit]- African-American Folk Artist Harriet Powers.

- Harriet Powers: A Freed Slave Tells Stories Through Quilting. Archived June 5, 2018, at the Wayback Machine

- Southern American quilting: Harriet Powers.

- Harriet Powers Film Project.

- Bible Quilt

- ^ Finch, Lucine (October 28, 1914). "A Sermon in Patchwork". The Outlook: With Illustrations. The Outlook: 493–495. Retrieved November 4, 2017.

- 19th-century American slaves

- American outsider artists

- American quilters

- 1837 births

- 1910 deaths

- African-American women artists

- Women outsider artists

- Religious artists

- Artists from Athens, Georgia

- 19th-century American textile artists

- 19th-century American women artists

- 20th-century American women artists

- 19th-century women textile artists

- 19th-century African-American women

- 20th-century African-American women

- Textile artists from Georgia (U.S. state)

- 19th-century African-American people