Hydroelectricity in Turkey: Difference between revisions

→Hydroelectric potential: moving text |

→Hydroelectric potential: unexcerpted as short |

||

| Line 12: | Line 12: | ||

=== Hydroelectric potential === |

=== Hydroelectric potential === |

||

In 2021 hydro was still the cheapest source of electricity,<ref name=":1" /> but the IEA expected both wind and solar to grow much faster than hydropower in the years to 2026.<ref>{{Cite web |title=Turkey's renewable power capacity to grow by 53% by 2026 |url=https://www.aa.com.tr/en/economy/turkeys-renewable-power-capacity-to-grow-by-53-by-2026/2437571 |access-date=2022-03-22 |website=www.aa.com.tr}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |title=Renewables 2021 – Analysis |url=https://www.iea.org/reports/renewables-2021 |access-date=2022-03-22 |website=IEA |language=en-GB}}</ref>{{Rp|pages=62,63}} But in 2022 the [[Ministry of Energy and Natural Resources (Turkey)|Energy Ministry]] website still said that there is "hydroelectricity potential of 433 billion kWh, while the technically usable potential is 216 billion kWh, and the economic hydroelectricity potential is 160 billion kWh/year"<ref>{{Cite web |title=Hydraulics |publisher=[[Ministry of Energy and Natural Resources (Turkey)]] |url=https://enerji.gov.tr/bilgi-merkezi-enerji-hidrolik-en |access-date=2022-03-12 |archive-date=2021-05-01 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210501101336/https://enerji.gov.tr/bilgi-merkezi-enerji-hidrolik-en |url-status=live }}</ref> (for comparison 56 billion kWh was generated in 2021). {{ |

In 2021 hydro was still the cheapest source of electricity,<ref name=":1" /> but the IEA expected both wind and solar to grow much faster than hydropower in the years to 2026.<ref>{{Cite web |title=Turkey's renewable power capacity to grow by 53% by 2026 |url=https://www.aa.com.tr/en/economy/turkeys-renewable-power-capacity-to-grow-by-53-by-2026/2437571 |access-date=2022-03-22 |website=www.aa.com.tr}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |title=Renewables 2021 – Analysis |url=https://www.iea.org/reports/renewables-2021 |access-date=2022-03-22 |website=IEA |language=en-GB}}</ref>{{Rp|pages=62,63}} But in 2022 the [[Ministry of Energy and Natural Resources (Turkey)|Energy Ministry]] website still said that there is "hydroelectricity potential of 433 billion kWh, while the technically usable potential is 216 billion kWh, and the economic hydroelectricity potential is 160 billion kWh/year"<ref>{{Cite web |title=Hydraulics |publisher=[[Ministry of Energy and Natural Resources (Turkey)]] |url=https://enerji.gov.tr/bilgi-merkezi-enerji-hidrolik-en |access-date=2022-03-12 |archive-date=2021-05-01 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210501101336/https://enerji.gov.tr/bilgi-merkezi-enerji-hidrolik-en |url-status=live }}</ref> (for comparison 56 billion kWh was generated in 2021). Reduced [[precipitation]]<ref>{{Citation|last1=Turkes|first1=Murat|title=Impacts of Climate Change on Precipitation Climatology and Variability in Turkey|date=2020|url=https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-11729-0_14|work=Water Resources of Turkey|pages=467–491|editor-last=Harmancioglu|editor-first=Nilgun B.|series=World Water Resources|place=Cham|publisher=Springer International Publishing|language=en|doi=10.1007/978-3-030-11729-0_14|isbn=978-3-030-11729-0|access-date=2020-10-24|last2=Turp|first2=M. Tufan|last3=An|first3=Nazan|last4=Ozturk|first4=Tugba|last5=Kurnaz|first5=M. Levent|editor2-last=Altinbilek|editor2-first=Dogan}}</ref> and [[hydroelectricity in Turkey]] is forecast,<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.futuredirections.org.au/publication/increasing-droughts-in-turkey-are-likely-to-put-pressure-on-its-hydropower-sector/|title=Increasing Droughts in Turkey are likely to put Pressure on its Hydropower Sector|date=2019-07-03|website=Future Directions International|language=en-AU|access-date=2019-07-11}}</ref> for example in the [[Tigris–Euphrates river system|Tigris and Euphrates river basins]], like the 2020 drought.<ref>{{Cite web|last=|first=|date=2021-02-08|title=Drought ramps up power output from gas in Turkey in 2020|url=https://www.dailysabah.com/business/energy/drought-ramps-up-power-output-from-gas-in-turkey-in-2020|url-status=live|access-date=2021-02-19|website=[[Daily Sabah]]|language=|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210208103223/https://www.dailysabah.com/business/energy/drought-ramps-up-power-output-from-gas-in-turkey-in-2020 |archive-date=2021-02-08 }}</ref> To conserve hydropower, [[Solar power in Turkey|solar power]] is being added next to the hydropower.<ref>{{Cite web|date=2021-02-08|title=Turkey expands renewables capacity in gigawatts rather than megawatts|url=https://balkangreenenergynews.com/turkey-expands-renewables-capacity-in-gigawatts-rather-than-megawatts/|access-date=2021-04-24|website=Balkan Green Energy News|language=en-US}}</ref> Due to changes in rainfall generation varies considerably from year to year, for example drought in 2020 caused a generation drop of over 10% compared to the previous year.<ref>{{Cite news|date=2021-01-06|title=Hydro plants' electricity generation down 12 pct|newspaper=[[Hürriyet Daily News]]|url=https://www.hurriyetdailynews.com/hydro-plants-electricity-generation-down-12-pct-161412|access-date=2021-01-07|archive-date=2021-01-06|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210106230821/https://www.hurriyetdailynews.com/hydro-plants-electricity-generation-down-12-pct-161412|url-status=live}}</ref> In 2021 non-hydro [[Renewable energy in Turkey|renewables]] overtook hydro for the first time, partly due to [[Drought in Turkey|drought]],<ref name=":11">{{Cite web|title=Turkey Electricity Review 2022|url=https://ember-climate.org/project/turkey-electricity-review-2022/|access-date=2022-01-20|website=[[Ember (non-profit organisation)|Ember]]|language=en-GB|archive-date=2022-01-20|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220120073531/https://ember-climate.org/project/turkey-electricity-review-2022/|url-status=live}}</ref> [[Solar power in Turkey|Solar power]] can be added to existing hydro plants, as has been done at [[Lower Kaleköy Dam|Lower Kaleköy]].<ref>{{Cite web |last=Todorović |first=Igor |date=2022-03-08 |title=Hybrid power plants dominate Turkey's new 2.8 GW grid capacity allocation |url=https://balkangreenenergynews.com/hybrid-power-plants-dominate-turkeys-new-2-8-gw-grid-capacity-allocation/ |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220308220824/https://balkangreenenergynews.com/hybrid-power-plants-dominate-turkeys-new-2-8-gw-grid-capacity-allocation/ |archive-date=2022-03-08 |access-date=2022-03-11 |website=Balkan Green Energy News |language=en-US}}</ref> Adding hydropower to existing [[irrigation]] dams may also be feasible.<ref>{{Cite web |last=Al Bayatı |first=Omar |last2=Kucukali |first2=Serhat |last3=Maraş |first3=Hakan |date=2022 |title=Finding the Most Suitable Irrigation Dams for Hydropower Development in Turkey Using Multi-Criteria Scoring and GIS Spatial Analysis Tool |url=https://www.springerprofessional.de/en/finding-the-most-suitable-irrigation-dams-for-hydropower-develop/20166496 |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220317041838/https://www.springerprofessional.de/en/finding-the-most-suitable-irrigation-dams-for-hydropower-develop/20166496 |archive-date=2022-03-17 |access-date=2022-03-11 |website=springerprofessional.de |language=en}}</ref> |

||

Some academics, such as those at [[Shura Energy Transition Center]], say that there is limited potential for more hydropower.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Saygin |first=D. |last2=Tör |first2=O. B. |last3=Cebeci |first3=M. E. |last4=Teimourzadeh |first4=S. |last5=Godron |first5=P. |date=2021-03-01 |title=Increasing Turkey's power system flexibility for grid integration of 50% renewable energy share |url=https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2211467X21000110 |url-status=live |journal=Energy Strategy Reviews |language=en |volume=34 |pages=100625 |doi=10.1016/j.esr.2021.100625 |issn=2211-467X |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220111144650/https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2211467X21000110 |archive-date=2022-01-11 |access-date=2022-03-13}}</ref> However in 2021 the [[International Energy Agency]] (IEA) said that, in part due to long-term contracts for the private sector, they expected Turkey to build more hydropower.<ref name=":7">{{Cite web |date=2021 |title=Hydropower Special Market Report |url=https://iea.blob.core.windows.net/assets/83ff8935-62dd-4150-80a8-c5001b740e21/HydropowerSpecialMarketReport.pdf |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220107063939/https://iea.blob.core.windows.net/assets/83ff8935-62dd-4150-80a8-c5001b740e21/HydropowerSpecialMarketReport.pdf |archive-date=2022-01-07 |access-date=2022-03-12 |website=[[International Energy Agency]]}}</ref> But they said hydro is not properly paid for rapid (5 mins or less) [[Ancillary services (electric power)|grid services]].<ref name=":7" /> |

Some academics, such as those at [[Shura Energy Transition Center]], say that there is limited potential for more hydropower.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Saygin |first=D. |last2=Tör |first2=O. B. |last3=Cebeci |first3=M. E. |last4=Teimourzadeh |first4=S. |last5=Godron |first5=P. |date=2021-03-01 |title=Increasing Turkey's power system flexibility for grid integration of 50% renewable energy share |url=https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2211467X21000110 |url-status=live |journal=Energy Strategy Reviews |language=en |volume=34 |pages=100625 |doi=10.1016/j.esr.2021.100625 |issn=2211-467X |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220111144650/https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2211467X21000110 |archive-date=2022-01-11 |access-date=2022-03-13}}</ref> However in 2021 the [[International Energy Agency]] (IEA) said that, in part due to long-term contracts for the private sector, they expected Turkey to build more hydropower.<ref name=":7">{{Cite web |date=2021 |title=Hydropower Special Market Report |url=https://iea.blob.core.windows.net/assets/83ff8935-62dd-4150-80a8-c5001b740e21/HydropowerSpecialMarketReport.pdf |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220107063939/https://iea.blob.core.windows.net/assets/83ff8935-62dd-4150-80a8-c5001b740e21/HydropowerSpecialMarketReport.pdf |archive-date=2022-01-07 |access-date=2022-03-12 |website=[[International Energy Agency]]}}</ref> But they said hydro is not properly paid for rapid (5 mins or less) [[Ancillary services (electric power)|grid services]].<ref name=":7" /> |

||

Revision as of 14:17, 22 March 2022

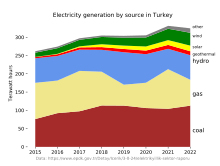

Hydroelectricity is a critical source of electricity in Turkey. In some years substantial amounts of it can be generated, due to Turkey's mountainous landscape and abundance of rivers. The main river basins are the Euphrates and the Tigris. Many dams have been built and hydroelectricity makes up about 30% of the country's electricity generating capacity. Generation can vary greatly from one year to the next depending on rainfall.[a] Many government policies supported dam construction. Some dams are controversial with neighbouring countries, and some because there are concerns about damage to the environment and wildlife of Turkey.[2]

56 TWh of hydroelectricity was generated in 2021, which was 17% of total electricity,[3] from 31 GW of capacity.[4] According to analysts S&P Global, when there is drought in Turkey during the peak electricity demand month of August, the aim of the State Hydraulic Works to conserve water for irrigation can conflict with the Turkish Electricity Transmission Corporation aiming to generate electricity.[5] Although energy strategy may change due to climate change causing more frequent droughts,[6] hydropower is predicted to remain important for load balancing of solar and wind power.[7]: 72 Converting existing dams to pumped storage has been suggested as more suitable than building new pumped storage.[8]

Water resources

Climate change has reduced rainfall in some regions and has made it less regular, which has put stress on hydroelectric power plants.[11] Between 1979 and 2019 annual precipitation fluctuated from over 60 cm to under 45 cm,[11] and average annual temperatures varied by 4 degrees.[11]

Turkey is already a water stressed country, because the amount of water per person is only about 1,500 m³ a year: and due to population increase and climate change it is highly likely the country will suffer water scarcity (less than 1,000 m³) by the 2070s.[12] Little change is forecast for water resources in the northern river basins, but a substantial reduction is forecast for the southern river basins.[12] Konya in central Turkey is also vulnerable.[13]Hydroelectric potential

In 2021 hydro was still the cheapest source of electricity,[5] but the IEA expected both wind and solar to grow much faster than hydropower in the years to 2026.[14][15]: 62, 63 But in 2022 the Energy Ministry website still said that there is "hydroelectricity potential of 433 billion kWh, while the technically usable potential is 216 billion kWh, and the economic hydroelectricity potential is 160 billion kWh/year"[16] (for comparison 56 billion kWh was generated in 2021). Reduced precipitation[17] and hydroelectricity in Turkey is forecast,[18] for example in the Tigris and Euphrates river basins, like the 2020 drought.[19] To conserve hydropower, solar power is being added next to the hydropower.[20] Due to changes in rainfall generation varies considerably from year to year, for example drought in 2020 caused a generation drop of over 10% compared to the previous year.[21] In 2021 non-hydro renewables overtook hydro for the first time, partly due to drought,[22] Solar power can be added to existing hydro plants, as has been done at Lower Kaleköy.[23] Adding hydropower to existing irrigation dams may also be feasible.[24]

Some academics, such as those at Shura Energy Transition Center, say that there is limited potential for more hydropower.[25] However in 2021 the International Energy Agency (IEA) said that, in part due to long-term contracts for the private sector, they expected Turkey to build more hydropower.[26] But they said hydro is not properly paid for rapid (5 mins or less) grid services.[26]

History

The first power plant of any kind in Turkey was a 60 kW hydro plant constructed in Tarsus, which started operation in 1902.[27] Feasibility studies for more dams were done in the 1920s and 1930s.[28] After the State Hydraulic Works (DSI) was established in 1954, projects (such as the first big dams, the Seyhan Dam and Sarıyar Dam[28]) were better funded and much more hydroelectricity was generated.[29] Turkey built dams to meet its growing energy demand with rapid urbanization, industrialization, and population growth.[28]

Following the 1973 oil crisis the government began the Southeastern Anatolia Project, both for energy security and to try and help the poorer south-east catch up with the growing economy.[28] Amongst other development such as irrigation, several hydropower plants were built.[30] In 1988 hydropower was over 60% of total generation: before that coal had been the only other main source but afterwards there was also natural gas.[22] The project cost 190.8 billion lira (US$ 34 billion, at 2020 prices).[31] According to Istanbul Chamber of Commerce this was paid back by 2021 by the value of the electricity alone.[30] However some Kurds called the project “mass cultural destruction”.[28] Most of the project has been completed, but at least one dam and hydroelectric power plant are still under construction,[32] namely Silvan Dam. The project is controversial with the downstream countries of Iraq and Syria.[33] According to academic Dr. Arda Bilgen, the reduced flow of the Euphrates was one reason why Syria supported PKK attacks on Turkey in the 1980s.[28] Almost 25% of the country’s hydroelectricity is produced by the project.[28][34] Since the Syrian Civil War started in 2011 international water cooperation has been very difficult.[28]

Since the beginning of the 21st century private companies have been able to get long leases on rivers,[35] and DSI has mainly coordinated and supervised rather than constructing its own power plants.[28] Particularly in the north-east small scale projects were developed but, contrary to expectations, did not bring more consensus and local acceptance than large dams.[35]

Between 1970 and 2019 generation increased at almost 10% per year.[36] And 2.5 GW was added during 2020.[4] 2021 was the first year in which generation from other renewables exceeded hydro.[22]

Projects

The geography of Turkey includes 25 river basins, and generally those with the most potential for hydropower are the least populated.[35] The private sector has generally invested in run-of-river and the public sector in dammed hydro.[35] Private sector water use agreements are usually for 49 years, with minimum discharge flow 10% of the last ten-year average.[35] There are over 700 hydropower plants, making up 31 GW of the country's 100 GW generating capacity.[27] The state electricity company owns 14 GW, and the only private companies with over 1 GW are Cengiz, EnerjiSA and Limak.[27] Water flow is greatest in spring but electricity demand is low, so the electricity price may also be low.[35] Another 4 GW is planned for after 2023.[35]

Like national energy policy as a whole,[37] decision making for dam construction is centralized and not always transparent, which can lead to complaints by local people.[35] The province with the most hydroelectricity capacity is Şanliurfa with over 3 GW, followed by Elazığ and Diyarbakır each with over 2 GW.[27] The highest dam is Yusufeli.[38]

Impacts on people and the environment

There have been both positive and negative environmental effects caused by the dams and hydroelectric power plants. One of the positive effects of hydroelectric power plants is dispatchable generation. Compared to fossil fuel power plants, the country's hydroelectricity produces much lower carbon emissions. Another positive impact is to limit energy imports, since Turkey imports around three-quarters of its energy.[39]

As well as environmental impact assessment reports before construction there are also water-usage studies and ecological evaluation: but according to a 2021 study by Melis Terzi, stipulations in the reports are sometimes ignored during construction.[35]: 74 The study also says that legal requirement to provide fish passages has often been ignored.[35] Large hydropower may be bad for sturgeon, as in neighbouring Georgia.[40] According to Bianet newspaper, sometimes small rivers have completely dried out in summer due to hydropower.[41] Fish, such as the kisslip himri, may be threatened with extinction, but this is unclear as no studies have been published since 2014.[42] Sediment management is sometimes not up to EU Water Framework Directive standard.[43] Turkey has not yet adopted the sustainability certification devised by the International Hydropower Association in 2021.[44] In some areas locals are concerned that dams decrease nature tourism.[35]

Tens of thousands of people have been displaced by reservoirs.[45] Archaeologists, such as Nevin Soyukaya, say that there has been disregard to ancient settlements, such of Assyrian, Greek, Armenian, and many more civilizations, such as at Hasankeyf.[46]

Dams on international rivers, such as the controversial Ilısu Dam on the Tigris completed in 2021, can cause water shortages in downstream countries, in this case Iraq and Syria.[47][33] Although international protests stopped foreign funding of the dam, Iraq and national protests were not political powerful enough to stop it being built with domestic funding.[48] There are also 14 Turkish dams on the international River Euphrates.[33] The Tigris and Euphrates are the main source of water for much of Iraq, and Iraqi academics say that Turkish dams on those rivers are damaging the environment of Iraq.[33] Although a Euphrates water sharing agreement was made in 1987 (500 cubic metres per second leaving Turkey[49]) this assumed the water flow would not reduce, which it has because of climate change in Turkey, thus the 2020s real flow is less than the total of the country's allocations in the agreement.[50]

In 2021 the Turkish company contracted to build Namakhvani hydropower plant in Georgia pulled out after protests.[51]

Economics

As of February 2022[update] the feed-in tariff (excluding domestic components incentive) was 400 lira/MWh (about 29 USD), more than solar and wind but less than geothermal.[52] However in late 2021 the government and private sector energy analysts predicted that the day ahead market price throughout 2022 would be higher than the FiT for the first year ever, thus resulting in a negative contract for difference.[52] By late March 2022 the spot price of electricity had reached the ceiling (thrice the average price over the past 12 months) of 1745 TL (over 115 USD),[53] and the Energy Ministry was reported to be considering different ceiling prices for different sources of electricity.[54] It is not yet known what the ceiling price of hydroelectricity will be.

Because transmission congestion of run-of-river can cause price imbalances, zonal pricing has been proposed.[55]

Politics

Many dams were built during Republican People's Party governments in the 20th century. The party's current stance on hydropower is unclear however, as its 2018 general election manifesto included no mention of it and the party has opposed many recent dam projects, mostly on the basis of environmental concerns.[56] The Justice and Development Party, which has been in power nationwide since 2002 (and with the support of the MHP since 2016), has also invested in hydroelectricity, building many dams and run-of-river hydro. According to its party program, the Good Party "supports the utilization of local and renewable resources to their fullest extent", which includes hydropower.[57] The Peoples' Democratic Party, in contrast, is "against those [...] who threaten the flora and fauna and pollute and exhaust [...] lakes and rivers with their [...] hydroelectric plants."[58]

Bilgen says that since the 1960s, the central government (inspired primarily by the Bureau of Reclamation in the United States) has used dam building to strengthen the central government's hold over Eastern and Southeastern Anatolia and to help grow these regions' economies with a top-down approach.[28]

Hydropower projects on the transboundary rivers Kura and Aras have been subject to criticism from local environmental activists and have also caused tensions between Turkey and downstream Caucasian countries, such as Azerbaijan.[59]

Turkey was one of three countries which voted against the 1997 UN Watercourses Convention, which is the main international water law. According to Nareg Kuyumjian at the Environmental Law Institute this was because Turkey benefited from "hydroanarchy".[59]

Energy storage and dispatchability

Hydropower usually peaks in April or May.[60] Converting existing dams to pumped to store wind and solar electricity has been suggested as more feasible than new pumped storage.[61] Although dammed hydro can be dispatched within 3 to 5 minutes[62] it has been reported that such generation instructions from the Turkish Electricity Transmission Corporation can be countermanded by the State Hydraulic Works, and that this was part of the cause of summer blackouts in 2021.[63]

Largest stations

The three longest rivers in Turkey[64] also have the largest power plants: the largest being Atatürk on the Euphrates. On the same river are the second and third largest: at Karakaya a 2011 study showed high levels of metal pollution affecting the organisms in the reservoir,[65] and for Keban about 25,000 people were resettled.[66] Ilısu on the Tigris is the newest large dam. In contrast the Kızılırmak flows north into the Black Sea and its hydro plants are less than 1 GW, the largest being Altınkaya.

Notes

References

- ^ "Hydro plants' electricity generation down 12 pct". Hürriyet Daily News. 2021-01-06. Archived from the original on 2021-01-06.

- ^ "Government to ease hydro plant construction for firms". Hurriyet Daily News. Archived from the original on 2017-10-01. Retrieved 2015-03-02.

- ^ "Aylık Elektrik Üretim-Tüketim Raporları" [Monthly Electricity Production-Consumption Reports]. Turkish Electricity Transmission Corporation. Archived from the original on 2022-02-18. Retrieved 2022-02-18.

- ^ a b "2021 Hydropower Status Report". International Hydropower Association. 11 June 2021. Archived from the original on 2022-03-07. Retrieved 2022-03-12.

- ^ a b O'Byrne, David (2021-08-09). "Turkey faces double whammy as low hydro aligns with gas contract expiries". S&P Global Commodity Insights. Archived from the original on 2021-08-22. Retrieved 2021-08-22.

- ^ "Confronting climate change, Turkey needs "green" leadership now more than ever". Middle East Institute. Retrieved 2022-03-22.

- ^ "Turkey Energy Outlook". Sabanci University Istanbul International Center for Energy and Climate. Archived from the original on 2021-10-06. Retrieved 2021-12-30.

- ^ Barbaros, Efe; Aydin, Ismail; Celebioglu, Kutay (2021-02-01). "Feasibility of pumped storage hydropower with existing pricing policy in Turkey". Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews. 136: 110449. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2020.110449. ISSN 1364-0321. Archived from the original on 2022-03-10. Retrieved 2021-01-07.

- ^ Baldasso, V.; Soncini, A.; Azzoni, R. S.; Diolaiuti, G.; Smiraglia, C.; Bocchiola, D. (2019-07-01). "Recent evolution of glaciers in Western Asia in response to global warming: the case study of Mount Ararat, Turkey". Theoretical and Applied Climatology. 137 (1–2): 45–59. Bibcode:2019ThApC.137...45B. doi:10.1007/s00704-018-2581-7. ISSN 0177-798X. S2CID 125700008.

- ^ Azzoni, Roberto Sergio; Sarıkaya, Mehmet Akif; Fugazza, Davide (2020-04-01). "Turkish glacier inventory and classification from high-resolution satellite data". Mediterranean Geoscience Reviews. 2 (1): 153–162. Bibcode:2020MGRv....2..153A. doi:10.1007/s42990-020-00029-2. hdl:2434/745029. ISSN 2661-8648. S2CID 216608789.

- ^ a b c Bulut, U; Sakalli, A (2021). "Impacts of climate change and distribution of precipitation on hydroelectric power generation in Turkey". IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering. 1032 (1). Article 012043. Bibcode:2021MS&E.1032a2043B. doi:10.1088/1757-899X/1032/1/012043. S2CID 234299802.

- ^ a b "Climate". climatechangeinturkey.com. Retrieved 2021-02-19.

- ^ Gedik, Furkan (2021). "Meteorological Drought Analysis in Konya Closed Basin". Journal of Geography (42): 295–308. doi:10.26650/JGEOG2021-885519.

- ^ "Turkey's renewable power capacity to grow by 53% by 2026". www.aa.com.tr. Retrieved 2022-03-22.

- ^ "Renewables 2021 – Analysis". IEA. Retrieved 2022-03-22.

- ^ "Hydraulics". Ministry of Energy and Natural Resources (Turkey). Archived from the original on 2021-05-01. Retrieved 2022-03-12.

- ^ Turkes, Murat; Turp, M. Tufan; An, Nazan; Ozturk, Tugba; Kurnaz, M. Levent (2020), Harmancioglu, Nilgun B.; Altinbilek, Dogan (eds.), "Impacts of Climate Change on Precipitation Climatology and Variability in Turkey", Water Resources of Turkey, World Water Resources, Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 467–491, doi:10.1007/978-3-030-11729-0_14, ISBN 978-3-030-11729-0, retrieved 2020-10-24

- ^ "Increasing Droughts in Turkey are likely to put Pressure on its Hydropower Sector". Future Directions International. 2019-07-03. Retrieved 2019-07-11.

- ^ "Drought ramps up power output from gas in Turkey in 2020". Daily Sabah. 2021-02-08. Archived from the original on 2021-02-08. Retrieved 2021-02-19.

- ^ "Turkey expands renewables capacity in gigawatts rather than megawatts". Balkan Green Energy News. 2021-02-08. Retrieved 2021-04-24.

- ^ "Hydro plants' electricity generation down 12 pct". Hürriyet Daily News. 2021-01-06. Archived from the original on 2021-01-06. Retrieved 2021-01-07.

- ^ a b c "Turkey Electricity Review 2022". Ember. Archived from the original on 2022-01-20. Retrieved 2022-01-20.

- ^ Todorović, Igor (2022-03-08). "Hybrid power plants dominate Turkey's new 2.8 GW grid capacity allocation". Balkan Green Energy News. Archived from the original on 2022-03-08. Retrieved 2022-03-11.

- ^ Al Bayatı, Omar; Kucukali, Serhat; Maraş, Hakan (2022). "Finding the Most Suitable Irrigation Dams for Hydropower Development in Turkey Using Multi-Criteria Scoring and GIS Spatial Analysis Tool". springerprofessional.de. Archived from the original on 2022-03-17. Retrieved 2022-03-11.

- ^ Saygin, D.; Tör, O. B.; Cebeci, M. E.; Teimourzadeh, S.; Godron, P. (2021-03-01). "Increasing Turkey's power system flexibility for grid integration of 50% renewable energy share". Energy Strategy Reviews. 34: 100625. doi:10.1016/j.esr.2021.100625. ISSN 2211-467X. Archived from the original on 2022-01-11. Retrieved 2022-03-13.

- ^ a b "Hydropower Special Market Report" (PDF). International Energy Agency. 2021. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-01-07. Retrieved 2022-03-12.

- ^ a b c d "Turkey's hydropower capacity grows despite drought lowering output". Hürriyet Daily News. 2 September 2021. Archived from the original on 2022-02-18. Retrieved 2022-03-11.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Lombardo, Joseph (December 2020). "Power and Politics of Turkey's Ongoing Hydroelectric Projects --an interview with Dr Arda Bilgen". Turkish Heritage Organization. Archived from the original on 2021-04-10. Retrieved 2022-03-13.

- ^ Dursun, Bahtiyar; Gokcol, Cihan (2011). "The role of hydroelectric power and contribution of small hydropower plants for sustainable development in Turkey". Renewable Energy. 36 (4): 1227–1235. doi:10.1016/j.renene.2010.10.001.

- ^ a b Kılıçlı, Şeref (25 March 2021). "Southeastern Anatolia Project as a global model". Istanbul Chamber of Commerce. Archived from the original on 2022-03-17. Retrieved 2022-03-11.

- ^ "GAP Regional Development Administration". gap.gov.tr. Archived from the original on 2022-02-06. Retrieved 2022-03-11.

- ^ Westcott, Tom (30 January 2022). "Iraq: Fishermen fear shrinking Lake Razzaza spells end to their livelihoods". Middle East Eye. Archived from the original on 2022-02-10. Retrieved 2022-02-10.

- ^ a b c d Al-Sulami, Mohammed (2021-11-29). "Region at risk due to divisive water policies". Arab News. Archived from the original on 2022-03-17. Retrieved 2022-02-10.

- ^ "GAP Regional Development Administration". gap.gov.tr. Archived from the original on 2022-02-06. Retrieved 2022-02-10.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Terzi, Melis (2021). "Environmental governance and legitimacy of hydropower development in Turkey". Norwegian University of Life Sciences. Archived from the original on 2022-02-10. Retrieved 2022-02-10.

- ^ Gökçin Özuyar, Pınar; Gürcan, Efe Can; Bayhantopçu, Esra (2021). "The Policy Orientation of Turkey's Current Climate Change Strategy". Belt & Road Initiative Quarterly. 2(3): 31–46. Archived from the original on 2022-03-17. Retrieved 2022-03-12.

- ^ Özkaynak, Begüm; Turhan, Ethemcan; Aydın, Cem İskender (2022-04-25). "The Politics of Energy in Turkey". The Oxford Handbook of Turkish Politics. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190064891.001.0001/oxfordhb-9780190064891-e-29. Archived from the original on 2022-03-17. Retrieved 2022-03-12.

- ^ "Yusufeli Dam & HEPP". Su-Yapı Engineering & Consulting Inc. Archived from the original on 2022-03-18. Retrieved 2022-03-17.

- ^ "Turkey 2021 – Analysis". International Energy Agency. Archived from the original on 2022-03-07. Retrieved 2022-03-17.

- ^ Jacob, Pearly (11 August 2021). "Hydropower dams threaten Georgia's haven for endangered sturgeon". Deutsche Welle. Archived from the original on 2022-03-11. Retrieved 2022-03-11.

- ^ "There are 246 active hydroelectric power plants in Turkey's Black Sea region". Bianet. 13 August 2021. Archived from the original on 13 August 2021. Retrieved 11 March 2022.

- ^ Freyhof, Jörg; Bergner, Laura; Ford, Matthew (2020). "Threatened Freshwater Fishes of the Mediterranean Basin Biodiversity Hotspot" (PDF). EuroNatur & RiverWatch. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-02-15. Retrieved 2022-03-17.

- ^ Kucukali, Serhat; Alp, Ahmet; Akyüz, Adil; Al Bayatı, Omar (2022), Sayigh, Ali (ed.), "Environmental Sustainability Assessment of Small Hydropower Plants: A Case Study from Ceyhan River Basin in Turkey", Sustainable Energy Development and Innovation: Selected Papers from the World Renewable Energy Congress (WREC) 2020, Innovative Renewable Energy, Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 699–706, doi:10.1007/978-3-030-76221-6_77, ISBN 978-3-030-76221-6, archived from the original on 2022-03-17, retrieved 2022-03-11

- ^ Pittock, Jamie (27 September 2021). "The hydropower industry is talking the talk. But fine words won't save our last wild rivers". The Conversation. Archived from the original on 2022-03-11. Retrieved 2022-03-11.

- ^ Harte, Julia (9 October 2018). "Turkish hydroelectric dam will leave hundreds homeless". Reuters. Archived from the original on 2022-02-10. Retrieved 2022-02-10.

- ^ Tastekin, Fehim (2017-08-24). "Turkish dam project would wipe out ancient town". Al-Monitor. Archived from the original on 2017-09-30. Retrieved 2017-09-30.

- ^ Hockenos, Paul (3 October 2019). "Turkey's Dam-Building Spree Continues, At Steep Ecological Cost". Yale E360. Archived from the original on 2019-10-05. Retrieved 2019-11-01.

- ^ Güneş, Murat Tezcür; Schiel, Rebecca; Wilson, Bruce M. (2021). "The Effectiveness of Harnessing Human Rights: The Struggle over the Ilısu Dam in Turkey" (PDF). doi:10.1111/dech.12690. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-03-17. Retrieved 2022-03-12.

- ^ Glynn, Sarah (14 June 2021). "Turkey is reportedly depriving hundreds of thousands of people of water". openDemocracy. Archived from the original on 2022-03-12. Retrieved 2022-03-12.

- ^ Sottimano, Aurora; Samman, Nabil (2022-02-24). "Syria has a water crisis. And it's not going away". Atlantic Council. Archived from the original on 2022-03-09. Retrieved 2022-03-11.

- ^ Mandaria, Tornike (24 September 2021). "Turkish company pulls out of controversial Georgian hydropower project". Eurasianet. Archived from the original on 2022-03-11. Retrieved 2022-03-11.

- ^ a b Kyrylo (2022-02-17). "(2022) Turkey's Feed-in Tariff For Renewable Energy Sources Support And YEKDEM 2022 Outlook". Future Energy Go. Archived from the original on 2022-03-17. Retrieved 2022-03-11.

- ^ "Spot Electricity Market".

- ^ Kozok, Firat (17 March 2022). "Turkey Plans Variable Prices for Power Plants to Tame Inflation". www.bloomberg.com. Retrieved 2022-03-22.

- ^ Selcuk, O.; Acar, B.; Dastan, S. A. (2022). "System integration costs of wind and hydropower generations in Turkey". Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews. 156 (C). Archived from the original on 2022-03-17. Retrieved 2022-03-11.

- ^ "Enerji santrallerini durdurmak için kırk takla atan CHP bugün "elektrik faturası" üzerinden sokak hareketleri planlıyor" [Republic Peoples Party, which went all out to stop power plants, plans street actions today on the "electricity bill"]. Takvim (in Turkish). 11 February 2022. Archived from the original on 2022-02-11. Retrieved 2022-03-17.

- ^ "Good Party Platform" (PDF) (in Turkish). Good Party. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2021-06-13. Retrieved 2022-03-14.

- ^ "HDP's Stance on Hydroelectricity". Peoples' Democratic Party (Turkey). 2022-03-14. Archived from the original on 2022-03-14. Retrieved 2022-03-14.

- ^ a b Kuyumjian, Nareg (28 December 2021). "Dam building on the Kura-Aras and water tensions in the Caucasus". Eurasianet. Archived from the original on 2022-03-13. Retrieved 2022-03-13.

- ^ "Turkish coal plants to widen their cost advantage in 2Q". Argus Media. 2021-02-23. Archived from the original on 2021-02-23. Retrieved 2021-03-01.

- ^ Barbaros, Efe; Aydin, Ismail; Celebioglu, Kutay (2021-02-01). "Feasibility of pumped storage hydropower with existing pricing policy in Turkey". Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews. 136: 110449. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2020.110449. ISSN 1364-0321. Archived from the original on 2022-03-10. Retrieved 2021-01-07.

- ^ Birpınar, Mehmet Emin (2021-08-31). "Does hydroelectricity help or damage Turkey? | Opinion". Daily Sabah. Archived from the original on 2021-08-31. Retrieved 2021-08-31.

- ^ O'Byrne, David (2021-08-09). "Turkey faces double whammy as low hydro aligns with gas contract expiries". S&P Global Commodity Insights. Archived from the original on 2021-08-22. Retrieved 2021-08-31.

- ^ Akbulut, Nuray (Emir); Bayarı, Serdar; Akbulut, Aydın; Özyurt, Naciye Nur; Sahin, Yalcın (2022-01-01), Tockner, Klement; Zarfl, Christiane; Robinson, Christopher T. (eds.), "Chapter 17 - Rivers of Turkey", Rivers of Europe (Second Edition), Elsevier, pp. 851–880, ISBN 978-0-08-102612-0, archived from the original on 2022-03-11, retrieved 2022-03-11

- ^ Gokce, Didem; Gökçe, Didem; Ozhan, Duygu (2011-12-16). "Limno-Ecological Properties of Deep Reservoir, Karakaya HEPP, Turkey". Gazi University Journal of Science. 24 (4): 663–669.

- ^ Bogumil Terminski, Development-Induced Displacement and Resettlement: Theoretical Frameworks and Current Challenges, Geneva, 2013; Bogumil Terminski, Development-Induced Displacement and Resettlement: Causes, Consequences and Socio-Legal Context, Ibidem Press, Stuttgart, 2015.