ZMapp: Difference between revisions

→History: replace 3 souorces with 1 recent review |

LeadSongDog (talk | contribs) →History: refs |

||

| Line 16: | Line 16: | ||

[[Image:monoclonal antibodies3.jpg|thumb|Researchers looking at slides of cultures of cells that make monoclonal antibodies. These are grown in a lab and the researchers are analyzing the products to select the most promising antibodies.]] |

[[Image:monoclonal antibodies3.jpg|thumb|Researchers looking at slides of cultures of cells that make monoclonal antibodies. These are grown in a lab and the researchers are analyzing the products to select the most promising antibodies.]] |

||

The composite drug is being developed by [[Leaf Biopharmaceutical]], |

The composite drug is being developed by [[Leaf Biopharmaceutical]] (LeafBio, Inc.), a San Diego based arm of [[Mapp Biopharmaceutical]].<ref>{{official |date=15 July 2014 |url=http://www.leafbio.com/zmab.pdf |title=Monoclonal antibody-based filovirus therapeutic licensed to Leaf Biopharmaceutical}}</ref> LeafBio created ZMapp in collaboration with its parent and [[Defyrus Inc.]], each of which had developed its own cocktail of antibodies, called MB-003 and ZMab. |

||

===MB-003=== |

===MB-003=== |

||

MB-003 is a cocktail of three human or human–mouse chimeric mAbs: c13C6, h13F6 and c6D8.<ref name=Nature2014/> A study published in September 2012 found that [[rhesus macaques]] infected with [[Ebola virus]] (EBOV) survived when receiving MB-003 (mixture of 3 chimeric monoclonal antibodies) one hour after infection. When treated 24 or 48 hours after infection, four of six animals survived and had little to no [[viremia]] and few, if any, clinical symptoms.<ref name=Zeitlin2012>{{cite journal |author=Olinger GG, Pettitt J, Kim D, ''et al.'' |title=Delayed treatment of Ebola virus infection with plant-derived monoclonal antibodies provides protection in rhesus macaques |journal=Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. |volume=109 |issue=44 |pages=18030–5 | |

MB-003 is a cocktail of three human or human–mouse chimeric mAbs: c13C6, h13F6 and c6D8.<ref name=Nature2014/> A study published in September 2012 found that [[rhesus macaques]] infected with [[Ebola virus]] (EBOV) survived when receiving MB-003 (mixture of 3 chimeric monoclonal antibodies) one hour after infection. When treated 24 or 48 hours after infection, four of six animals survived and had little to no [[viremia]] and few, if any, clinical symptoms.<ref name=Zeitlin2012>{{cite journal |author=Olinger GG, Pettitt J, Kim D, ''et al.'' |title=Delayed treatment of Ebola virus infection with plant-derived monoclonal antibodies provides protection in rhesus macaques |journal=Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. |volume=109 |issue=44 |pages=18030–5 |date=October 2012 |pmid=23071322 |pmc=3497800 |doi=10.1073/pnas.1213709109}}</ref> |

||

MB-003 was created by [[Mapp Biopharmaceutical]], based in San Diego, with years of funding from US government agencies including the [[National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease]], [[Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority]], and the [[Defense Threat Reduction Agency]].<ref name=Kroll>{{cite news|first=David|last=Kroll|publisher=Forbes|date=5 August 2014|url=http://www.forbes.com/sites/davidkroll/2014/08/05/ebola-secret-serum-small-biopharma-the-army-and-big-tobacco/|title=Ebola 'Secret Serum': Small Biopharma, The Army, And Big Tobacco}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|publisher=Centers for Disease Control and Prevention|date= |

MB-003 was created by [[Mapp Biopharmaceutical]], based in San Diego, with years of funding from US government agencies including the [[National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease]], [[Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority]], and the [[Defense Threat Reduction Agency]].<ref name=Kroll>{{cite news |first=David |last=Kroll |publisher=Forbes |date=5 August 2014|url=http://www.forbes.com/sites/davidkroll/2014/08/05/ebola-secret-serum-small-biopharma-the-army-and-big-tobacco/ |title=Ebola 'Secret Serum': Small Biopharma, The Army, And Big Tobacco}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |publisher=Centers for Disease Control and Prevention |date=29 August 2014 |url=http://www.cdc.gov/vhf/ebola/outbreaks/guinea/qa-experimental-treatments.html |title=Questions and answers on experimental treatments and vaccines for Ebola}}</ref> |

||

===ZMAb=== |

===ZMAb=== |

||

ZMAb is a cocktail of three mouse mAbs: m1H3, m2G4 and m4G7.<ref name=Nature2014/> A study published in November 2013 found that EBOV-infected [[macaque]] monkeys survived after being given a therapy with a combination of three EBOV surface [[glycoprotein]] (EBOV-GP)-specific monoclonal antibodies (ZMAb) within 24 hours of infection. The authors concluded that post-exposure treatment and a second lethal exposure after 10 and 13 weeks resulted in a robust immune response.<ref name=ZMAbStudy>{{cite journal |author=Qiu X, Audet J, Wong G, ''et al.'' |title=Sustained protection against Ebola virus infection following treatment of infected nonhuman primates with ZMAb |journal=Sci Rep |volume=3 |issue= |pages=3365 |year=2013 |pmid=24284388 |pmc=3842534 |doi=10.1038/srep03365}}</ref> |

ZMAb is a cocktail of three mouse mAbs: m1H3, m2G4 and m4G7.<ref name=Nature2014/> A study published in November 2013 found that EBOV-infected [[macaque]] monkeys survived after being given a therapy with a combination of three EBOV surface [[glycoprotein]] (EBOV-GP)-specific monoclonal antibodies (ZMAb) within 24 hours of infection. The authors concluded that post-exposure treatment and a second lethal exposure after 10 and 13 weeks resulted in a robust immune response.<ref name=ZMAbStudy>{{cite journal |author=Qiu X, Audet J, Wong G, ''et al.'' |title=Sustained protection against Ebola virus infection following treatment of infected nonhuman primates with ZMAb |journal=Sci Rep |volume=3 |issue= |pages=3365 |year=2013 |pmid=24284388 |pmc=3842534 |doi=10.1038/srep03365}}</ref> |

||

ZMab was created by [[Defyrus]], a Toronto-based [[biodefense]] company, funded by the [[Public Health Agency of Canada]].<ref name=Branswell>{{cite news|first=Helen |last=Branswell|publisher=Canadian Press|date=5 August 2014|url=http://www.brandonsun.com/business/breaking-news/experimental-ebola-drug-based-on-research-discoveries-from-canadas-national-lab-269910211.html|title=Experimental Ebola drug based on research discoveries from Canada's national lab}}</ref> The identification of the optimal components from MB-003 and ZMab was carried out at the Public Health Agency of Canada’s [[National Microbiology Laboratory]] in Winnipeg.<ref name=Branswell2>{{cite news|first=Helen |last=Branswell|publisher=Canadian Press|date=29 August 2014|url=http://www.macleans.ca/society/health/scientists-at-canadas-national-lab-created-tested-ebola-drug-zmapp/|title=Scientists at Canada’s |

ZMab was created by [[Defyrus]], a Toronto-based [[biodefense]] company, funded by the [[Public Health Agency of Canada]].<ref name=Branswell>{{cite news|first=Helen |last=Branswell|publisher=Canadian Press|date=5 August 2014|url=http://www.brandonsun.com/business/breaking-news/experimental-ebola-drug-based-on-research-discoveries-from-canadas-national-lab-269910211.html|title=Experimental Ebola drug based on research discoveries from Canada's national lab}}</ref> The identification of the optimal components from MB-003 and ZMab was carried out at the Public Health Agency of Canada’s [[National Microbiology Laboratory]] in Winnipeg.<ref name=Branswell2>{{cite news |first=Helen |last=Branswell |publisher=Macleans |agency=Canadian Press|date=29 August 2014 |url=http://www.macleans.ca/society/health/scientists-at-canadas-national-lab-created-tested-ebola-drug-zmapp/ |title=Scientists at Canada’s national lab created, tested Ebola drug ZMapp}}</ref> |

||

===ZMapp=== |

===ZMapp=== |

||

| Line 33: | Line 33: | ||

In an experiment also published in the 2014 paper, 21 [[rhesus macaque]] primates were infected with the [[Kikwit]] Congolese variant of EBOV. Three primates in the control arm were given a non-functional antibody, and the 18 in the treatment arm were divided into three groups of six. All primates in the treatment arm received three doses of ZMapp, spaced 3 days apart. The first treatment group received its first dose on 3rd day after being infected; the second group on the 4th day after being infected, and the third group, on the 5th day after being infected. All three primates in the control group died; all 18 primates in the treatment arm survived.<ref name=Nature2014/> Mapp then went on to show that ZMapp inhibits replication of a Guinean strain of EBOV in cell cultures.<ref name=NatureNews2014>{{cite journal |author=Geisbert TW |title=Medical research: Ebola therapy protects severely ill monkeys |journal=Nature |volume= |issue= |pages= | date=August 2014 |pmid=25171470 |doi=10.1038/nature13746}}</ref> |

In an experiment also published in the 2014 paper, 21 [[rhesus macaque]] primates were infected with the [[Kikwit]] Congolese variant of EBOV. Three primates in the control arm were given a non-functional antibody, and the 18 in the treatment arm were divided into three groups of six. All primates in the treatment arm received three doses of ZMapp, spaced 3 days apart. The first treatment group received its first dose on 3rd day after being infected; the second group on the 4th day after being infected, and the third group, on the 5th day after being infected. All three primates in the control group died; all 18 primates in the treatment arm survived.<ref name=Nature2014/> Mapp then went on to show that ZMapp inhibits replication of a Guinean strain of EBOV in cell cultures.<ref name=NatureNews2014>{{cite journal |author=Geisbert TW |title=Medical research: Ebola therapy protects severely ill monkeys |journal=Nature |volume= |issue= |pages= | date=August 2014 |pmid=25171470 |doi=10.1038/nature13746}}</ref> |

||

Mapp remains involved in the production of the drug through its contracts with Kentucky BioProcessing, a subsidiary of [[Reynolds American]].<ref name=Kroll/> To create a system to produce the chimeric mAbs at commercial scale, Mapp used a process called "Rapid Antibody Manufacturing Platform" (RAMP), using magnICON (ICON Genetics) [[viral vectors]]. In a rapid and scalable process called "magnifection,"<ref>{{cite web|title=Magnifection – mass-producing drugs in record time|url=http://phenomena.nationalgeographic.com/2008/08/16/magnifection-mass-producing-drugs-in-record-time/|publisher=National Geographic|accessdate=11 September 2014}}</ref> tobacco plants are infected with the viral vector encoding for the antibodies, using ''[[Agrobacterium]]'' cultures.<ref>Whaley KJ et al. Emerging antibody-based products. |

Mapp remains involved in the production of the drug through its contracts with Kentucky BioProcessing, a subsidiary of [[Reynolds American]].<ref name=Kroll/> To create a system to produce the chimeric mAbs at commercial scale, Mapp used a process called "Rapid Antibody Manufacturing Platform" (RAMP), using magnICON (ICON Genetics) [[viral vectors]]. In a rapid and scalable process called "magnifection,"<ref>{{cite web|title=Magnifection – mass-producing drugs in record time|url=http://phenomena.nationalgeographic.com/2008/08/16/magnifection-mass-producing-drugs-in-record-time/|publisher=National Geographic|accessdate=11 September 2014}}</ref> tobacco plants are infected with the viral vector encoding for the antibodies, using ''[[Agrobacterium]]'' cultures.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Whaley KJ et al. |title=Emerging antibody-based products |journal=Curr Top Microbiol Immunol |year=2014 |volume=375 |pages=107-26 |pmid=22772797}}</ref> Subsequently, antibodies are extracted and purified from the plants. Once the genes encoding the chimeric mAbs are in hand, the entire tobacco production cycle is believed to take a few months.<ref name=NYTwho>{{cite news |url=http://www.nytimes.com/2014/08/09/health/in-ebola-outbreak-who-should-get-experimental-drug.html |date=8 August 2014 |newspaper=The New York Times |title=In Ebola outbreak, who should get experimental drug?|last=Pollack|first=Andrew}}</ref> The development of these production methods was funded by the U.S. [[DARPA|Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency]] as part of its bio-defense efforts following the 9/11 terrorist attacks.<ref>{{cite news |first=Brian |last=Till |newspaper=New Republic |date=9 September 2014 |url=http://www.newrepublic.com/article/119376/ebola-drug-zmapp-darpa-program-could-get-it-africa |title=DARPA may have a way to stop Ebola in its tracks}}</ref><ref>{{cite news|publisher=BBC Radio 4 |work=File on Four |title=Ebola |broadcastdate=21 October 2014 |url=http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b04lq2yg }}</ref> |

||

Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2014;375:107-26. PMID 22772797</ref> Subsequently, antibodies are extracted and purified from the plants. Once the genes encoding the chimeric mAbs are in hand, the entire tobacco production cycle is believed to take a few months.<ref name=NYTwho>{{cite news |url=http://www.nytimes.com/2014/08/09/health/in-ebola-outbreak-who-should-get-experimental-drug.html |date=8 August 2014 |newspaper=The New York Times |title=In Ebola outbreak, who should get experimental drug?|last=Pollack|first=Andrew}}</ref> The development of these production methods was funded by [[DARPA|Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency]] as part of its bio-defense efforts following the 9/11 terrorist attacks.<ref>{{cite news|first=Brian|last=Till|newspaper=New Republic|date=9 September 2014 |url=http://www.newrepublic.com/article/119376/ebola-drug-zmapp-darpa-program-could-get-it-africa |title=DARPA may have a way to stop Ebola in its tracks}}</ref><ref>BBC Radio 4 "File on Four" programme Ebola, first broadcast 21 October 2014 </ref> |

|||

[[File:Agroinfiltration.jpg|thumb|ALT=green plant being injected by a needle|The ''[[Nicotiana benthamiana]]'' tobacco plant]] |

[[File:Agroinfiltration.jpg|thumb|ALT=green plant being injected by a needle|The ''[[Nicotiana benthamiana]]'' tobacco plant]] |

||

Revision as of 19:05, 24 October 2014

ZMapp is an experimental biopharmaceutical drug comprising three chimeric monoclonal antibodies under development as a treatment for Ebola virus disease. The drug was first tested in humans during the 2014 West Africa Ebola virus outbreak and was credited as helping save lives, but has not been subjected to a randomized controlled trial to determine its safety or its efficacy.

Medical use

ZMapp is under development as a treatment for Ebola virus disease.[2] It was first used experimentally to treat some people with Ebola virus disease during the 2014 West African Ebola outbreak, but as of August 2014 it had not yet been tested in a clinical trial to support widespread usage in humans; it is not known whether it is effective to treat the disease, nor if it is safe.[3][4][5]

Mechanism of action

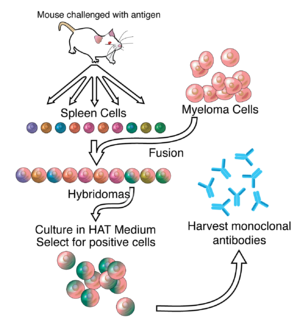

Like intravenous immunoglobulin therapy, ZMapp contains neutralizing antibodies[6] that provide passive immunity to the virus by directly and specifically reacting with it in a "lock and key" fashion.[7]

Physical and chemical properties

The drug is composed of three monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) that have been chimerized by genetic engineering.[8] The components are chimeric monoclonal antibody c13C6 from a previously existing antibody cocktail called "MB-003" and two chimeric mAbs from a different antibody cocktail called ZMab, c2G4 and c4G7.[2]

ZMapp is manufactured in the tobacco plant Nicotiana benthamiana in the bioproduction process known as "pharming" by Kentucky BioProcessing, a subsidiary of Reynolds American.[1][9][10]

History

The composite drug is being developed by Leaf Biopharmaceutical (LeafBio, Inc.), a San Diego based arm of Mapp Biopharmaceutical.[11] LeafBio created ZMapp in collaboration with its parent and Defyrus Inc., each of which had developed its own cocktail of antibodies, called MB-003 and ZMab.

MB-003

MB-003 is a cocktail of three human or human–mouse chimeric mAbs: c13C6, h13F6 and c6D8.[2] A study published in September 2012 found that rhesus macaques infected with Ebola virus (EBOV) survived when receiving MB-003 (mixture of 3 chimeric monoclonal antibodies) one hour after infection. When treated 24 or 48 hours after infection, four of six animals survived and had little to no viremia and few, if any, clinical symptoms.[12]

MB-003 was created by Mapp Biopharmaceutical, based in San Diego, with years of funding from US government agencies including the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease, Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority, and the Defense Threat Reduction Agency.[1][13]

ZMAb

ZMAb is a cocktail of three mouse mAbs: m1H3, m2G4 and m4G7.[2] A study published in November 2013 found that EBOV-infected macaque monkeys survived after being given a therapy with a combination of three EBOV surface glycoprotein (EBOV-GP)-specific monoclonal antibodies (ZMAb) within 24 hours of infection. The authors concluded that post-exposure treatment and a second lethal exposure after 10 and 13 weeks resulted in a robust immune response.[14]

ZMab was created by Defyrus, a Toronto-based biodefense company, funded by the Public Health Agency of Canada.[15] The identification of the optimal components from MB-003 and ZMab was carried out at the Public Health Agency of Canada’s National Microbiology Laboratory in Winnipeg.[16]

ZMapp

A 2014 paper described how Mapp and its collaborators, including investigators at Public Health Agency of Canada, Kentucky BioProcessing, and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, first chimerized the three antibodies comprising ZMAb, then tested combinations of MB-003 and the chimeric ZMAb antibodies in guinea pigs and then primates to determine the best combination, which turned out to be c13C6 from MB-003 and two chimeric mAbs from ZMAb, c2G4 and c4G7. This is ZMapp.[2]

In an experiment also published in the 2014 paper, 21 rhesus macaque primates were infected with the Kikwit Congolese variant of EBOV. Three primates in the control arm were given a non-functional antibody, and the 18 in the treatment arm were divided into three groups of six. All primates in the treatment arm received three doses of ZMapp, spaced 3 days apart. The first treatment group received its first dose on 3rd day after being infected; the second group on the 4th day after being infected, and the third group, on the 5th day after being infected. All three primates in the control group died; all 18 primates in the treatment arm survived.[2] Mapp then went on to show that ZMapp inhibits replication of a Guinean strain of EBOV in cell cultures.[17]

Mapp remains involved in the production of the drug through its contracts with Kentucky BioProcessing, a subsidiary of Reynolds American.[1] To create a system to produce the chimeric mAbs at commercial scale, Mapp used a process called "Rapid Antibody Manufacturing Platform" (RAMP), using magnICON (ICON Genetics) viral vectors. In a rapid and scalable process called "magnifection,"[18] tobacco plants are infected with the viral vector encoding for the antibodies, using Agrobacterium cultures.[19] Subsequently, antibodies are extracted and purified from the plants. Once the genes encoding the chimeric mAbs are in hand, the entire tobacco production cycle is believed to take a few months.[20] The development of these production methods was funded by the U.S. Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency as part of its bio-defense efforts following the 9/11 terrorist attacks.[21][22]

Experimental availability

Compassionate use during the 2014 Ebola outbreak

The FDA has allowed two drugs, ZMapp and an RNA interference drug called TKM-Ebola, to be used in Americans suffering from Ebola virus disease.[23] Other countries have similar programs to allow early access through named patient programs.[24][25]

As of October 2014, ZMapp had been used to treat 7 individuals infected with the Ebola virus.[26] Although some of them have recovered, the outcome is not considered to be statistically significant.[5]

In August 2014, Samaritan's Purse worked with the FDA and Mapp Biopharmaceutical to make the drug available to two of its health workers who were infected by the Ebola virus during their work in Liberia.[20] At the time, there were only a few doses of ZMapp in existence.[20] Both workers received the drug and were transported to the US, where they recovered and were then released from the hospital.[27][28][29] A 75-year-old Spanish priest who was infected with Ebola virus in Liberia received ZMapp in cooperation with Spanish health authorities, and died shortly thereafter.[30][31]

The west African nation of Liberia secured enough ZMapp to treat three Liberians with the disease, one of whom died.[32] A British nurse who contracted Ebola virus disease while working in Sierra Leone, was transported to the UK and treated with ZMapp, and recovered.[33][34] Mapp announced on August 11, 2014, that its supplies of ZMapp had been exhausted.[35]

Controversy

The lack of drugs and unavailability of experimental treatment in the most affected regions of the West African Ebola virus outbreak spurred some controversy.[20]

On August 6, 2014, Peter Piot (co-discoverer of the Ebola virus) and other scientists, including the director of the Wellcome Trust, called for the release of ZMapp for affected African nations.[36] The fact that the drug was first given to Americans and a European and not to Africans, according to the Los Angeles Times, "provoked outrage, feeding into African perceptions of Western insensitivity and arrogance, with a deep sense of mistrust and betrayal still lingering over the exploitation and abuses of the colonial era".[36]

Salim S. Abdool Karim, the director of an AIDS research center in South Africa, placed the issue in the context of the history of exploitation and abuses. Responding to a question on how people may have reacted if ZMapp and other drugs would have been used first on Africans, said, "It would have been the front-page screaming headline: 'Africans used as guinea pigs for American drug company’s medicine'".[20]

Regarding whether the cocktail should be fast-tracked for approval or be made available to sick patients outside of the United States, their president stated on August 6, 2014, "I think we have to let the science guide us".[37]

See also

References

- ^ a b c d Kroll, David (5 August 2014). "Ebola 'Secret Serum': Small Biopharma, The Army, And Big Tobacco". Forbes.

- ^ a b c d e f Qiu X, Wong G, Audet J; et al. (August 2014). "Reversion of advanced Ebola virus disease in nonhuman primates with ZMapp". Nature. doi:10.1038/nature13777. PMID 25171469.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "WHO Experts Give Nod to Using Untested Ebola Drugs". August 12, 2014.

- ^ "WHO – Ethical considerations for use of unregistered interventions for Ebola virus disease". World Health Organization. Retrieved 8 October 2014.

- ^ a b "How Will We Know If The Ebola Drugs Worked?". Forbes. Retrieved 10 September 2014.

- ^ "Ebola 'cocktail' developed at Canadian and U.S. labs". CBC News. 2014-08-05.

- ^ Keller MA, Stiehm ER (October 2000). "Passive immunity in prevention and treatment of infectious diseases". Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 13 (4): 602–14. doi:10.1128/CMR.13.4.602-614.2000. PMC 88952. PMID 11023960.

- ^ Pollack, Andrew (29 August 2014). "Experimental Drug Would Help Fight Ebola if Supply Increases, Study Finds". The New York Times. Retrieved 1 September 2014.

- ^ Parshley, Lois (8 August 2014). "ZMapp: The Experimental Ebola Treatment Explained". Popular Science.

- ^ Daniel, Fran (12 August 2014). "Ebola drug provided for two Americans by Reynolds American subsidiary". Winston-Salem Journal.

- ^ Official website

- ^ Olinger GG, Pettitt J, Kim D; et al. (October 2012). "Delayed treatment of Ebola virus infection with plant-derived monoclonal antibodies provides protection in rhesus macaques". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109 (44): 18030–5. doi:10.1073/pnas.1213709109. PMC 3497800. PMID 23071322.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Questions and answers on experimental treatments and vaccines for Ebola". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 29 August 2014.

- ^ Qiu X, Audet J, Wong G; et al. (2013). "Sustained protection against Ebola virus infection following treatment of infected nonhuman primates with ZMAb". Sci Rep. 3: 3365. doi:10.1038/srep03365. PMC 3842534. PMID 24284388.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Branswell, Helen (5 August 2014). "Experimental Ebola drug based on research discoveries from Canada's national lab". Canadian Press.

- ^ Branswell, Helen (29 August 2014). "Scientists at Canada's national lab created, tested Ebola drug ZMapp". Macleans. Canadian Press.

- ^ Geisbert TW (August 2014). "Medical research: Ebola therapy protects severely ill monkeys". Nature. doi:10.1038/nature13746. PMID 25171470.

- ^ "Magnifection – mass-producing drugs in record time". National Geographic. Retrieved 11 September 2014.

- ^ Whaley KJ; et al. (2014). "Emerging antibody-based products". Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 375: 107–26. PMID 22772797.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - ^ a b c d e Pollack, Andrew (8 August 2014). "In Ebola outbreak, who should get experimental drug?". The New York Times.

- ^ Till, Brian (9 September 2014). "DARPA may have a way to stop Ebola in its tracks". New Republic.

- ^ "Ebola". File on Four. BBC Radio 4.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|broadcastdate=ignored (help) - ^ Pollack, Andrew (7 August 2014). "Second drug is allowed for treatment of Ebola". The New York Times. Retrieved 8 August 2014.

- ^ Helene S (2010). "EU Compassionate Use Programmes (CUPs): Regulatory Framework and Points to Consider before CUP Implementation". Pharm Med. 24 (4): 223–229. doi:10.1007/bf03256820.

- ^ "Spain imports US experimental Ebola drug to treat priest evacuated from Liberia with disease". First Word Pharma. 11 August 2014.

- ^ "US signs contract with ZMapp maker to accelerate development of the Ebola drug". BMJ. BMJ. 2014. Retrieved 9 October 2014.

- ^ "Ebola patient got experimental serum, missionary group says". Los Angeles Times. 3 August 2014.

- ^ "American doctor treated for Ebola released from hospital". Reuters. 21 August 2014.

- ^ "Can you really recover from Ebola?". The Telegraph. 22 August 2014.

- ^ "Spanish priest infected with Ebola to receive experimental treatment". Aljazeera. 11 August 2014.

- ^ John Bacon, Karen Weintraub (12 August 2014). "Spanish missionary doctor infected with Ebola dies". USA Today.

- ^ "Ebola kills Liberia doctor despite ZMapp treatment". BBC News. 25 August 2014.

- ^ "UK Ebola patient gets experimental drug". BBC News. 26 August 2014. Retrieved 26 August 2014.

- ^ Dassanayake, Dion (1 September 2014). "First British Ebola victim recovering 'pretty well' after being given experimental drug". Express. Retrieved 2014-09-11.

- ^ Lenny M. Bernstein, Brady Dennis (11 August 2014). "Ebola test drug's supply 'exhausted' after shipments to Africa, U.S. company says". Washington Post.

- ^ a b Dixon, Robyn (6 August 2014). "Three leading Ebola experts call for release of experimental drug". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ "Obama: 'Premature' to say U.S. should green-light new Ebola drug". NBC News. 6 August 2014.