Early modern human: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

merging AMH, some redundancy to be worked out. |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{about|''Homo sapiens'' as a biological species (its evolution and habitat)|a more general perspective on humanity|Human|other uses|Homo sapiens (disambiguation)}} |

{{about|''Homo sapiens'' as a biological species (its evolution and habitat)|a more general perspective on humanity|Human|other uses|Homo sapiens (disambiguation)}} |

||

{{pp-vandalism|small=yes}} |

{{pp-vandalism|small=yes}} |

||

{{main|Human taxonomy|Anatomically modern human}} |

|||

{{speciesbox |

{{speciesbox |

||

| fossil_range = {{Fossil range|0.3|0}} <small>[[Middle Pleistocene]]–[[Holocene|Present]]</small> |

| fossil_range = {{Fossil range|0.3|0}} <small>[[Middle Pleistocene]]–[[Holocene|Present]]</small> |

||

| Line 24: | Line 23: | ||

The age of speciation of ''H. sapiens'' out of ancestral ''H. erectus'' (or an intermediate species such as ''[[Homo heidelbergensis]]'') is estimated to have taken place at roughly 300,000 years ago. |

The age of speciation of ''H. sapiens'' out of ancestral ''H. erectus'' (or an intermediate species such as ''[[Homo heidelbergensis]]'') is estimated to have taken place at roughly 300,000 years ago. |

||

Sustained [[Archaic human admixture with modern humans|archaic admixture]] is known to have taken place both in Africa and (following the [[Coastal migration|recent Out-Of-Africa expansion]]) in Eurasia, between about 100,000 to 30,000 years ago. |

Sustained [[Archaic human admixture with modern humans|archaic admixture]] is known to have taken place both in Africa and (following the [[Coastal migration|recent Out-Of-Africa expansion]]) in Eurasia, between about 100,000 to 30,000 years ago. |

||

In certain contexts, the term '''anatomically modern humans'''<ref>Nitecki, Matthew H. and Nitecki, Doris V. (1994). ''Origins of Anatomically Modern Humans''. Springer.</ref> ('''AMH''') is used to distinguish ''H. sapiens'' as having an [[Human anatomy|anatomy]] consistent with the [[Human variability|range of phenotypes]] seen in [[human|contemporary humans]] from varieties of extinct [[archaic humans]]. This is useful especially for times and regions where anatomically modern and archaic humans co-existed, e.g. in [[Paleolithic Europe]]. |

|||

== Name and taxonomy == |

== Name and taxonomy == |

||

| Line 30: | Line 31: | ||

The [[binomial nomenclature|binomial name]] ''Homo sapiens'' was coined by [[Carl Linnaeus]] (1758).<ref>{{cite book|last=Linné|first=Carl von|title=Systema naturæ. Regnum animale.|year=1758|pages=18, 20|url=https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/item/80764#page/28/mode/1up|edition=10th|accessdate=19 November 2012}}.</ref> |

The [[binomial nomenclature|binomial name]] ''Homo sapiens'' was coined by [[Carl Linnaeus]] (1758).<ref>{{cite book|last=Linné|first=Carl von|title=Systema naturæ. Regnum animale.|year=1758|pages=18, 20|url=https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/item/80764#page/28/mode/1up|edition=10th|accessdate=19 November 2012}}.</ref> |

||

The [[Latin]] noun ''[[wikt:homo#Latin|homō]]'' (genitive ''hominis'') means "human being." |

The [[Latin]] noun ''[[wikt:homo#Latin|homō]]'' (genitive ''hominis'') means "human being." |

||

The species is taken to have emerged from a predecessor within the ''[[Homo]]'' genus around 200,000 to 300,000 years ago.<ref>This is a matter of convention (rather than a factual dispute), and there is no universal consensus on terminology. |

|||

Some scholars include humans of up to 600,000 years ago under the same species. See [https://books.google.com/books?isbn=0761925147 Handbook of Death and Dying], Volume 1. Clifton D. Bryant. 2003. p. 811. |

|||

See also: [https://books.google.com/books?isbn=1137000384 Masters of the Planet]: The Search for Our Human Origins. Ian Tattersall. Page 82 (''cf''. Unfortunately this consensus in principle hardly clarifies matters much in practice. For there is no agreement on what the 'qualities of a man' actually are," [...]).</ref> |

|||

Extant human populations have historically been divided into [[Human subspecies|subspecies]], but since c. the 1980s all extant groups tend to be subsumed into a single species, ''H. sapiens'', avoiding division into subspecies altogether.<ref>The history of claimed or proposed subspecies of ''H. sapiens'' is complicated and fraught with controversy. The only widely recognized archaic subspecies is ''[[Homo sapiens idaltu|H. sapiens idaltu]]'' (2003). |

Extant human populations have historically been divided into [[Human subspecies|subspecies]], but since c. the 1980s all extant groups tend to be subsumed into a single species, ''H. sapiens'', avoiding division into subspecies altogether.<ref>The history of claimed or proposed subspecies of ''H. sapiens'' is complicated and fraught with controversy. The only widely recognized archaic subspecies is ''[[Homo sapiens idaltu|H. sapiens idaltu]]'' (2003). |

||

| Line 45: | Line 49: | ||

{{further|Human evolution|Homo|Timeline of human evolution|Early human migrations}} |

{{further|Human evolution|Homo|Timeline of human evolution|Early human migrations}} |

||

[[File:Homo lineage 2017update.svg|thumb|Schematic representation of the emergence of ''H. sapiens'' from earlier species of ''Homo''. The horizontal axis represents geographic location; the vertical axis represents time in [[Myr|millions of years ago]] (blue areas denote the presence of a certain species of ''Homo'' at a given time and place; late survival of [[robust australopithecines]] alongside ''Homo'' is indicated in purple). Based on Springer (2012), ''Homo heidelbergensis''<ref>{{cite journal | last=Stringer | first=C. | title=What makes a modern human | journal=Nature | year=2012 | volume=485 | issue=7396 | pages=33–35 | doi=10.1038/485033a | pmid=22552077}}</ref> is shown as diverging into Neanderthals, Denisovans and ''H. sapiens''. With the rapid expansion of ''H. sapiens'' after 60 kya, Neanderthals, Denisovans and unspecified archaic African hominins are shown as again subsumed into the ''H. sapiens'' lineage.]] |

[[File:Homo lineage 2017update.svg|thumb|Schematic representation of the emergence of ''H. sapiens'' from earlier species of ''Homo''. The horizontal axis represents geographic location; the vertical axis represents time in [[Myr|millions of years ago]] (blue areas denote the presence of a certain species of ''Homo'' at a given time and place; late survival of [[robust australopithecines]] alongside ''Homo'' is indicated in purple). Based on Springer (2012), ''Homo heidelbergensis''<ref>{{cite journal | last=Stringer | first=C. | title=What makes a modern human | journal=Nature | year=2012 | volume=485 | issue=7396 | pages=33–35 | doi=10.1038/485033a | pmid=22552077}}</ref> is shown as diverging into Neanderthals, Denisovans and ''H. sapiens''. With the rapid expansion of ''H. sapiens'' after 60 kya, Neanderthals, Denisovans and unspecified archaic African hominins are shown as again subsumed into the ''H. sapiens'' lineage.]] |

||

===Derivation from ''H. erectus''=== |

|||

[[File:Homo sapiens lineage.svg|thumb|300px|A model of the phylogeny of ''H. sapiens'' during the [[Middle Paleolithic]]. The horizontal axis represents geographic location; the vertical axis represents time in [[Year#Abbreviations yr and ya|thousands of years ago]].<ref>based on |

|||

Schlebusch et al., "Southern African ancient genomes estimate modern human divergence to 350,000 to 260,000 years ago" |

|||

''Science'', 28 Sep 2017, [http://science.sciencemag.org/content/early/2017/09/27/science.aao6266.full DOI: 10.1126/science.aao6266], [https://d2ufo47lrtsv5s.cloudfront.net/content/sci/early/2017/09/27/science.aao6266/F3.large.jpg Fig. 3] (''H. sapiens'' divergence times) and |

|||

{{cite journal | last=Stringer | first=C. | title=What makes a modern human | journal=Nature | year=2012 | volume=485 | issue=7396 | pages=33–35 | doi=10.1038/485033a | pmid=22552077| bibcode=2012Natur.485...33S }} (archaic admixture).</ref> |

|||

''Homo heidelbergensis'' is shown as diverging into Neanderthals, Denisovans and ''H. sapiens''. With the expansion of ''H. sapiens'' after 200 kya, Neanderthals, Denisovans and unspecified archaic African hominins are shown as [[Archaic human admixture with modern humans|again subsumed]] into the ''H. sapiens'' lineage. In addition, admixture events in modern African populations are indicated.]] |

|||

The speciation of ''H. sapiens'' out of varieties of ''H. erectus'' is estimated as having taken place between 300,000 and 200,000 years ago. |

The speciation of ''H. sapiens'' out of varieties of ''H. erectus'' is estimated as having taken place between 300,000 and 200,000 years ago. |

||

The derivation of a comparatively homogeneous single species of ''Homo sapiens'' from more diverse varieties of [[archaic humans]] (all of which were descended from the dispersal of ''[[Homo erectus]]'' some 1.8 million years ago) was debated in terms of two competing models during the 1980s: "[[recent African origin]]" postulated the emergence of ''Homo sapiens'' from a single source population in Africa, which expanded and led to the extinction of all other human varieties, while the "[[multiregional evolution]]" model postulated the survival of regional forms of archaic humans, gradually converging into the [[human genetic variation|modern human varieties]] by the mechanism of [[cline (population genetics)|clinal variation]], via [[genetic drift]], [[gene flow]] and [[Natural selection|selection]] throughout the Pleistocene.<ref name="dx.doi.org">{{cite journal | last1 = Wolpoff | first1 = M. H. | last2 = Spuhler | first2 = J. N. | last3 = Smith | first3 = F. H. | last4 = Radovcic | first4 = J. | last5 = Pope | first5 = G. | last6 = Frayer | first6 = D. W. | last7 = Eckhardt | first7 = R. | last8 = Clark | first8 = G. | year = 1988 | title = Modern Human Origins | url = | journal = Science | volume = 241 | issue = 4867| pages = 772–4 | doi = 10.1126/science.3136545 | pmid=3136545| bibcode = 1988Sci...241..772W }}</ref> |

|||

Since the 2000s, the availability of date from [[archaeogenetics]] and [[population genetics]] has led to the emergence of a much more detailed picture, intermediate between the two competing scenarios outlined above: The [[recent African origin|recent Out-of-Africa]] expansion accounts for the predominant part of modern human ancestry, while there were also significant [[Archaic human admixture with modern humans|admixture events]] with regional archaic humans.<ref>{{cite journal | last1 = Green | first1 = RE | last2 = Krause | first2 = J | last3 = Briggs | first3 = Adrian W. | last4 = Maricic | first4 = Tomislav | last5 = Stenzel | first5 = Udo | last6 = Kircher | first6 = Martin | last7 = Patterson | first7 = Nick | last8 = Li | first8 = Heng | last9 = Zhai | first9 = Weiwei | last10 = Fritz | first10 = Markus Hsi-Yang | last11 = Hansen | first11 = Nancy F. | last12 = Durand | first12 = Eric Y. | last13 = Malaspinas | first13 = Anna-Sapfo | last14 = Jensen | first14 = Jeffrey D. | last15 = Marques-Bonet | first15 = Tomas | last16 = Alkan | first16 = Can | last17 = Prüfer | first17 = Kay | last18 = Meyer | first18 = Matthias | last19 = Burbano | first19 = Hernán A. | last20 = Good | first20 = Jeffrey M. | last21 = Schultz | first21 = Rigo | last22 = Aximu-Petri | first22 = Ayinuer | last23 = Butthof | first23 = Anne | last24 = Höber | first24 = Barbara | last25 = Höffner | first25 = Barbara | last26 = Siegemund | first26 = Madlen | last27 = Weihmann | first27 = Antje | last28 = Nusbaum | first28 = Chad | last29 = Lander | first29 = Eric S. | last30 = Russ | first30 = Carsten | name-list-format=vanc |date=May 2010 | title = A draft sequence of the Neandertal genome | journal = Science | volume = 328 | issue = 5979| pages = 710–22 | doi = 10.1126/science.1188021 | pmid = 20448178 |bibcode = 2010Sci...328..710G | display-authors = 29 | pmc=5100745}} |

|||

{{cite journal | last1 = Reich | first1 = D | last2 = Patterson | first2 = Nick | last3 = Kircher | first3 = Martin | last4 = Delfin | first4 = Frederick | last5 = Nandineni | first5 = Madhusudan R. | last6 = Pugach | first6 = Irina | last7 = Ko | first7 = Albert Min-Shan | last8 = Ko | first8 = Ying-Chin | last9 = Jinam | first9 = Timothy A. | last10 = Phipps | first10 = Maude E. | last11 = Saitou | first11 = Naruya | last12 = Wollstein | first12 = Andreas | last13 = Kayser | first13 = Manfred | last14 = Pääbo | first14 = Svante | last15 = Stoneking | first15 = Mark | name-list-format=vanc | year = 2011 | title = Denisova admixture and the first modern human dispersals into southeast Asia and oceania | url = | journal = Am J Hum Genet | volume = 89 | issue = 4| pages = 516–28 | doi = 10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.09.005 | pmid = 21944045 | pmc=3188841}}</ref> |

|||

Since the 1970s, the [[Omo remains]], dated to some 195,000 years ago, have often been taken as the conventional cut-off point for the emergence of "[[anatomically modern humans]]". Since the 2000s, the discovery of older remains with comparable characteristics, and the discovery of ongoing hybridization between "modern" and "archaic" populations after the time of the Omo remains, have opened up a renewed debate on the "age of ''Homo sapiens''", |

Since the 1970s, the [[Omo remains]], dated to some 195,000 years ago, have often been taken as the conventional cut-off point for the emergence of "[[anatomically modern humans]]". Since the 2000s, the discovery of older remains with comparable characteristics, and the discovery of ongoing hybridization between "modern" and "archaic" populations after the time of the Omo remains, have opened up a renewed debate on the "age of ''Homo sapiens''", |

||

| Line 56: | Line 73: | ||

''[[Homo sapiens idaltu]]'', dated to 160,000 years ago, has been postulated as an extinct subspecies of ''Homo sapiens'' in 2003.<ref>[http://www.anth.ucsb.edu/projects/human/# Human evolution: the fossil evidence in 3D], by Philip L. Walker and Edward H. Hagen, Dept. of Anthropology, University of California, Santa Barbara. Retrieved April 5, 2005.</ref> |

''[[Homo sapiens idaltu]]'', dated to 160,000 years ago, has been postulated as an extinct subspecies of ''Homo sapiens'' in 2003.<ref>[http://www.anth.ucsb.edu/projects/human/# Human evolution: the fossil evidence in 3D], by Philip L. Walker and Edward H. Hagen, Dept. of Anthropology, University of California, Santa Barbara. Retrieved April 5, 2005.</ref> |

||

''[[Neanderthal|Homo neanderthalensis]]'', which became extinct 30,000 years ago, has also been classified as a subspecies, ''Homo sapiens neanderthalensis''; genetic studies now suggest that the functional DNA of modern humans and Neanderthals diverged 500,000 years ago.<ref>{{cite book |author=Green, R. E. |author2=Krause, J |author3=Ptak, S. E. |author4=Briggs, A. W. |author5=Ronan, M. T. |author6=Simons, J. F.|year=2006 |title=Analysis of one million base pairs of Neanderthal DNA |publisher=Nature |pages= 16, 330–336 |url=http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v444/n7117/abs/nature05336.html|display-authors=etal}}</ref> |

''[[Neanderthal|Homo neanderthalensis]]'', which became extinct 30,000 years ago, has also been classified as a subspecies, ''Homo sapiens neanderthalensis''; genetic studies now suggest that the functional DNA of modern humans and Neanderthals diverged 500,000 years ago.<ref>{{cite book |author=Green, R. E. |author2=Krause, J |author3=Ptak, S. E. |author4=Briggs, A. W. |author5=Ronan, M. T. |author6=Simons, J. F.|year=2006 |title=Analysis of one million base pairs of Neanderthal DNA |publisher=Nature |pages= 16, 330–336 |url=http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v444/n7117/abs/nature05336.html|display-authors=etal}}</ref> |

||

===Early ''Homo sapiens''=== |

|||

{{see|Homo sapiens|Human subspecies|Middle Paleolithic|Archaic human admixture with modern humans|Homo sapiens idaltu}} |

|||

[[File:Skhul.JPG|thumb|right|200px|[[Skhul V]] (c. 100,000 BC) exhibiting a mix of archaic and modern traits.]] |

|||

The term [[Middle Paleolithic]] is intended to cover the time between the first emergence of ''Homo sapiens'' (roughly 300,000 years ago) and the emergence of full [[behavioral modernity]] (roughly 50,000 years ago). |

|||

Many of the early modern human finds, like those of [[Omo remains|Omo]], [[homo sapiens idaltu|Herto]], [[Skhul remains|Skhul]], and [[Peștera cu Oase]] exhibit a mix of archaic and modern traits.<ref name="Oppenheimer">{{cite book |last=Oppenheimer |first=S. |title=Out of Eden: The Peopling of the World |year=2003 |publisher= |location= |isbn=1-84119-697-5}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal | doi = 10.1073/pnas.2035108100 | last1 = Trinkaus | first1 = E. | last2 = Moldovan | first2 = O. | last3 = Milota | first3 = Ș. | last4 = Bîlgăr | first4 = A. | last5 = Sarcina | first5 = L. | last6 = Athreya | first6 = S. | last7 = Bailey | first7 = S. E. | last8 = Rodrigo | first8 = R. | last9 = Gherase | first9 = M. | last10 = Higham | first10 = T. | last11 = Ramsey | first11 = C. B. | last12 = Van Der Plicht | first12 = J. | year = 2003 | title = An early modern human from Peștera cu Oase, Romania | url = | journal = PNAS | volume = 100 | issue = 20| pages = 11231–11236 | pmid=14504393 | pmc=208740 | bibcode=2003PNAS..10011231T| display-authors = 8 }}</ref> Skhul V, for example, has prominent brow ridges and a projecting face. However, the [[Neurocranium|brain case]] is quite rounded and distinct from that of the Neanderthals and is similar to the brain case of modern humans. It is now known that modern humans north of Sahara and outside of Africa have some [[Archaic human admixture with modern humans|archaic human admixture]], though whether the robust traits of some of the early modern humans like Skhul V reflects mixed ancestry or retention of older traits is uncertain.<ref name="Reich et al.">{{Cite journal|first=David |last=Reich |

|||

|first2=Richard E. |last2=Green |

|||

|first3=Martin |last3=Kircher |

|||

|first4=Johannes |last4=Krause |

|||

|first5=Nick |last5=Patterson |

|||

|first6=Eric Y. |last6=Durand |

|||

|first7=Bence |last7=Viola |

|||

|first8=Adrian W. |last8=Briggs |

|||

|first9=Udo |last9=Stenzel |

|||

|first10=Philip L. F. |last10=Johnson |

|||

|first11=Tomislav |last11=Maricic |

|||

|first12=Jeffrey M. |last12=Good |

|||

|first13=Tomas |last13=marques-Bonet |

|||

|first14=Can |last14=Alkan |

|||

|first15=Qiaomei |last15=Fu |

|||

|first16=Swapan |last16=Mallick |

|||

|first17=Heng |last17=Li |

|||

|first18=Matthias |last18=Meyer |

|||

|first19=Evan E. |last19=Eichler |

|||

|first20=Mark |last20=Stoneking |

|||

|first21=Michael |last21=Richards |

|||

|first22=Sahra |last22=Talamo |

|||

|first23=Michael V. |last23=Shunkov |

|||

|first24=Anatoli P. |last24=Derevianko |

|||

|first25=Jean-Jacques |last25=Hublin |

|||

|first26=Janet |last26=Kelso |

|||

|first27=Montgomery |last27=Slatkin |lastauthoramp=yes |first28=Svante |last28=Pääbo |display-authors=8 |year=2010 |title=Genetic history of an archaic hominin group from Denisova Cave in Siberia |journal=[[Nature (journal)|Nature]] |volume=468 |issue=7327 |pages=1053–1060 |doi=10.1038/nature09710 |pmid=21179161|bibcode = 2010Natur.468.1053R |pmc=4306417 |

|||

}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal|last=Trinkaus|first=Erik|title=Early modern humans|journal=Annual Review of Anthropology|date=October 2005|volume=34|issue=1|pages=207–30|doi=10.1146/annurev.anthro.34.030905.154913}}</ref> |

|||

The "gracile" or lightly built skeleton of anatomically modern humans has been connected to a change in behavior, including increased cooperation and "resource transport".<ref>{{cite book|author1=Meldrum, Jeff |author2=Hilton, Charles E. |title=From Biped to Strider: The Emergence of Modern Human Walking, Running, and Resource Transport|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=IfIWVrxg-hEC|date=31 March 2004|publisher=Springer Science & Business Media|isbn=978-0-306-48000-3}} |

|||

{{cite book|author1=Vonk, Jennifer |author2=Shackelford, Todd K. |title=The Oxford Handbook of Comparative Evolutionary Psychology|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=btS8XyqTY6MC&pg=PA429|date=13 February 2012|publisher=Oxford University Press, USA|isbn=978-0-19-973818-2|pages=429–}}</ref> |

|||

There is evidence that the characteristic human brain development, especially the prefrontal cortex, was due to "an exceptional acceleration of metabolome evolution ... paralleled by a drastic reduction in muscle strength. The observed rapid metabolic changes in brain and muscle, together with the unique human cognitive skills and low muscle performance, might reflect parallel mechanisms in human evolution."<ref>{{cite journal |doi=10.1371/journal.pbio.1001871|pmid=24866127|title=Exceptional Evolutionary Divergence of Human Muscle and Brain Metabolomes Parallels Human Cognitive and Physical Uniqueness|journal=PLoS Biology|volume=12|issue=5|pages=e1001871|year=2014|last1=Bozek|first1=Katarzyna|last2=Wei|first2=Yuning|last3=Yan|first3=Zheng|last4=Liu|first4=Xiling|last5=Xiong|first5=Jieyi|last6=Sugimoto|first6=Masahiro|last7=Tomita|first7=Masaru|last8=Pääbo|first8=Svante|last9=Pieszek|first9=Raik|last10=Sherwood|first10=Chet C.|last11=Hof|first11=Patrick R.|last12=Ely|first12=John J.|last13=Steinhauser|first13=Dirk|last14=Willmitzer|first14=Lothar|last15=Bangsbo|first15=Jens|last16=Hansson|first16=Ola|last17=Call|first17=Josep|last18=Giavalisco|first18=Patrick|last19=Khaitovich|first19=Philipp|pmc=4035273}} |

|||

</ref> |

|||

The [[Schöningen spears]] and their correlation of finds are evidence of complex technological skills already 300,000 years ago and are the first obvious proof for an active [[Big game hunting|(big game) hunt]]. |

|||

''[[H. heidelbergensis]]'' already had intellectual and cognitive skills like anticipatory planning, thinking and acting that so far have only been attributed to modern man.<ref>Thieme H. (2007). "Der große Wurf von Schöningen: Das neue Bild zur Kultur des frühen Menschen", pp. 224–228 in Thieme H. (ed.) ''Die Schöninger Speere – Mensch und Jagd vor 400 000 Jahren''. Konrad Theiss Verlag, Stuttgart {{ISBN|3-89646-040-4}}</ref><ref>Haidle M.N. (2006) "Menschenaffen? Affenmenschen? Mensch! Kognition und Sprache im Altpaläolithikum", pp. 69–97 in Conard N.J. (ed.) ''Woher kommt der Mensch''. Attempto Verlag. Tübingen {{ISBN|3-89308-381-2}}</ref> |

|||

The ongoing admixture events within anatomically modern human populations make it difficult to give an estimate on the age of the matrilinear and patrilinear most recent common ancestors of modern populations ([[Mitochondrial Eve]] and [[Y-chromosomal Adam]]). |

|||

Estimates on the age of Y-chromosomal Adam have been pushed back significantly with the discovery of an ancient Y-chromosomal lineage in 2013, likely beyond 300,000 years ago.<ref>{{Citation |

|||

|last1=Mendez|first1=Fernando |

|||

|last2=Krahn|first2=Thomas |

|||

|last3=Schrack|first3=Bonnie |

|||

|last4=Krahn|first4=Astrid-Maria |

|||

|last5=Veeramah|first5=Krishna |

|||

|last6=Woerner|first6=August |

|||

|last7=Fomine|first7=Forka Leypey Mathew |

|||

|last8=Bradman|first8=Neil |

|||

|last9=Thomas|first9=Mark |

|||

|title=An African American paternal lineage adds an extremely ancient root to the human Y chromosome phylogenetic tree |

|||

|journal=[[American Journal of Human Genetics]] |

|||

|date=7 March 2013 |

|||

|doi=10.1016/j.ajhg.2013.02.002 |

|||

|url=http://haplogroup-a.com/Ancient-Root-AJHG2013.pdf |

|||

|volume=92 |

|||

|issue=3 |

|||

|pages=454–59 |

|||

|pmid=23453668|pmc=3591855}} |

|||

(95% confidence interval 237–581 kya) |

|||

</ref> |

|||

There has, however, been no reports of the survival of Y-chromosomal or mitochondrial DNA clearly deriving from archaic humans (which would push back the age of the most recent patrilinear or matrilinear ancestor beyond 500,000 years).<ref>{{cite journal |vauthors=Krings M, Stone A, Schmitz RW, Krainitzki H, Stoneking M, Pääbo S |title=Neandertal DNA sequences and the origin of modern humans |journal=Cell |volume=90 |issue=1 |pages=19–30 |date=July 1997 |pmid=9230299 |doi=10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80310-4}} |

|||

Hill, Deborah (16 March 2004) [http://www.sciencemag.org/news/2004/03/no-neandertals-gene-pool No Neandertals in the Gene Pool], ''Science''. |

|||

{{cite journal|last=Serre|year=2004|title=No evidence of Neandertal mtDNA contribution to early modern humans|journal=PLoS Biology|volume=2|issue=3|pages=313–7|pmid=15024415|doi=10.1371/journal.pbio.0020057|last2=Langaney|first2=A|last3=Chech|first3=M|last4=Teschler-Nicola|first4=M|last5=Paunovic|first5=M|last6=Mennecier|first6=P|last7=Hofreiter|first7=M|last8=Possnert|first8=G|last9=Pääbo|first9=S|pmc=368159|first1=D|authorlink4=Maria Teschler-Nicola}}</ref> |

|||

==Dispersal and archaic admixture== |

==Dispersal and archaic admixture== |

||

| Line 66: | Line 152: | ||

Evidence presented in 2017 raises the possibility that a yet earlier migration, dated to around 270,000 years ago, may have left traces of admixture in Neanderthal genome.<ref name="NC-20170704">{{cite journal |last=Posth |first=Cosimo |display-authors=etal |title=Deeply divergent archaic mitochondrial genome provides lower time boundary for African gene flow into Neanderthals |url=https://www.nature.com/articles/ncomms16046 |date=4 July 2017 |journal=[[Nature Communications]] |doi=10.1038/ncomms16046 |accessdate=4 July 2017 }}</ref> |

Evidence presented in 2017 raises the possibility that a yet earlier migration, dated to around 270,000 years ago, may have left traces of admixture in Neanderthal genome.<ref name="NC-20170704">{{cite journal |last=Posth |first=Cosimo |display-authors=etal |title=Deeply divergent archaic mitochondrial genome provides lower time boundary for African gene flow into Neanderthals |url=https://www.nature.com/articles/ncomms16046 |date=4 July 2017 |journal=[[Nature Communications]] |doi=10.1038/ncomms16046 |accessdate=4 July 2017 }}</ref> |

||

The [[Recent African origin of modern humans|Recent "Out of Africa" migration]] of ''Homo sapiens'' took place in at least two waves, the first around 130,000 to 100,000 years ago, the second ([[Southern Dispersal]]) around 70,000 to 60,000 years ago |

The [[Recent African origin of modern humans|Recent "Out of Africa" migration]] of ''Homo sapiens'' took place in at least two waves, the first around 130,000 to 100,000 years ago, the second ([[Southern Dispersal]]) around 70,000 to 60,000 years ago, |

||

resulting in the colonization of Australia around 65,000 years ago,<ref>Chris Clarkson et al. (2017), [https://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v547/n7663/full/nature22968.html Human occupation of northern Australia by 65,000 years ago], Nature. doi:10.1038/nature22968. |

|||

{{cite news|last1=St. Fleu|first1=Nicholas|title=Humans First Arrived in Australia 65,000 Years Ago, Study Suggests|url=https://www.nytimes.com/2017/07/19/science/humans-reached-australia-aboriginal-65000-years.html|publisher=New York Times|date=July 19, 2017}}</ref> |

|||

while [[Paleolithic Europe|Europe]] was populated by [[European early modern humans|an early offshoot]] which settled the Near East and Europe by around 50,000 years ago. |

|||

Evidence for the overwhelming contribution of the "recent African origin" of modern populations outside of Africa was established based on [[mitochondrial DNA]], combined with evidence based on [[physical anthropology]] of archaic [[Biological specimen|specimens]], during the 1990s and 2000s.<ref>{{cite journal | last1 = Liu | first1 = Hua | display-authors = etal | year = 2006 | title = A Geographically Explicit Genetic Model of Worldwide Human-Settlement History | doi = 10.1086/505436 | journal = The American Journal of Human Genetics | volume = 79 | issue = 2| pages = 230–237 | quote = Currently available genetic and archaeological evidence is generally interpreted as supportive of a recent single origin of modern humans in East Africa. | pmid=16826514 | pmc=1559480}} |

Evidence for the overwhelming contribution of the "recent African origin" of modern populations outside of Africa was established based on [[mitochondrial DNA]], combined with evidence based on [[physical anthropology]] of archaic [[Biological specimen|specimens]], during the 1990s and 2000s.<ref>{{cite journal | last1 = Liu | first1 = Hua | display-authors = etal | year = 2006 | title = A Geographically Explicit Genetic Model of Worldwide Human-Settlement History | doi = 10.1086/505436 | journal = The American Journal of Human Genetics | volume = 79 | issue = 2| pages = 230–237 | quote = Currently available genetic and archaeological evidence is generally interpreted as supportive of a recent single origin of modern humans in East Africa. | pmid=16826514 | pmc=1559480}} |

||

{{cite journal|url=http://www.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/summary/sci;308/5724/921g |title=Out of Africa Revisited |doi=10.1126/science.308.5724.921g |date=2005-05-13 |accessdate=2009-11-23 |volume=308 |issue=5724 |journal=Science |page=921g}}</ref> |

{{cite journal|url=http://www.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/summary/sci;308/5724/921g |title=Out of Africa Revisited |doi=10.1126/science.308.5724.921g |date=2005-05-13 |accessdate=2009-11-23 |volume=308 |issue=5724 |journal=Science |page=921g}}</ref> |

||

| Line 75: | Line 165: | ||

</ref> |

</ref> |

||

Cumulatively, about 20% of the Neanderthal genome is estimated to remain present in contemporary populations.<ref name=vern14res>{{cite journal| last=Vernot| first=B.|author2=Akey, J. M.| title=Resurrecting Surviving Neandertal Lineages from Modern Human Genomes| journal=Science| date=2014| volume=343 |issue=6174 |pages=1017–1021| doi=10.1126/science.1245938| pmid=24476670|bibcode=2014Sci...343.1017V}}</ref> |

Cumulatively, about 20% of the Neanderthal genome is estimated to remain present in contemporary populations.<ref name=vern14res>{{cite journal| last=Vernot| first=B.|author2=Akey, J. M.| title=Resurrecting Surviving Neandertal Lineages from Modern Human Genomes| journal=Science| date=2014| volume=343 |issue=6174 |pages=1017–1021| doi=10.1126/science.1245938| pmid=24476670|bibcode=2014Sci...343.1017V}}</ref> |

||

==Anatomy== |

|||

{{see also|Human anatomy|Human physical appearance|Human variability}} |

|||

Generally, modern humans are more lightly built than [[archaic humans]] from which they have evolved. Humans are a highly variable species; modern humans can show remarkably robust traits, and early modern humans even more so. Despite this, modern humans differ from archaic people (the [[Neanderthal]]s and [[Denisovan]]s) in a range of anatomical details. |

|||

===Anatomical modernity=== |

|||

The term "anatomically modern humans" (AMH) is used with varying scope depending on context, to distinguish "anatomically modern" ''Homo sapiens'' from |

|||

[[archaic humans]] such as [[Neanderthals]]. |

|||

In a convention popular in the 1990s, Neanderthals were classified as a [[human subspecies|subspecies]] of ''H. sapiens'', as ''H. s. neanderthalensis'', while AMH (or [[European early modern humans]], EEMH) was taken to refer to "[[Cro-Magnon]]" or ''H. s. sapiens''. |

|||

Under this nomenclature (Neanderthals considered ''H. sapiens''), the term "anatomically modern ''Homo sapiens''" (AMHS) has also been used to refer to EEMH ("Cro-Magnons").<ref>{{cite book|author=Schopf, J. William |title=Major Events in the History of Life|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=py01HMuAIh4C&pg=PA168|year=1992|publisher=Jones & Bartlett Learning|isbn=978-0-86720-268-7|pages=168–}}</ref> |

|||

It has since become more common to designate Neanderthals as a separate species, ''H. neanderthalensis'', so that AMH in the European context refers to ''H. sapiens'' (but the question is by no means resolved<ref>It is important to note that this is a question of conventional terminology, not one of a factual disagreement. Pääbo (2014) frames this as a debate that is unresolvable in principle, "since there is no definition of species perfectly describing the case."{{cite book|last=Pääbo|first=Svante|title=Neanderthal Man: In Search of Lost Genomes|publisher=Basic Books|location=New York|year=2014|page=237}}</ref>). |

|||

In this more narrow definition of ''Homo sapiens'', the subspecies ''[[Homo sapiens idaltu|H. s. idaltu]]'', discovered in 2003, also falls under the umbrella of "anatomically modern".<ref>Robert Sanders, [http://www.berkeley.edu/news/media/releases/2003/06/11_idaltu.shtml 160,000-year-old fossilized skulls uncovered in Ethiopia are oldest anatomically modern humans], | 11 June 2003</ref> |

|||

The recognition of ''[[Homo sapiens idaltu]]'' as a [[human subspecies|valid subspecies]] of the anatomically modern human lineage would justify the description of contemporary humans with the subspecies name ''[[Homo sapiens sapiens]]''.<!--H. s. idaltu was proposed in 2003 and is not universally recognized -- there can never by a single subspecies, and "H. s. sapiens" is only permissible as a systematic name if at least one other subspecies is recognized--> |

|||

A further division of AMH into "early" or "robust" vs. "post-glacial" or "gracile" subtypes has since been used for convenience. |

|||

The emergence of "gracile AMH" is taken to reflect a process towards a smaller and more fine-boned skeleton beginning around 50,000–30,000 years ago.<ref>{{cite journal |doi= 10.1073/pnas.0707650104|title= Recent acceleration of human adaptive evolution|journal= Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences|volume= 104|issue= 52|pages= 20753|year= 2007|last1= Hawks|first1= J.|last2= Wang|first2= E. T.|last3= Cochran|first3= G. M.|last4= Harpending|first4= H. C.|last5= Moyzis|first5= R. K.|bibcode= 2007PNAS..10420753H|pmid=18087044|pmc=2410101}}</ref> |

|||

The following is a list of human varieties which lived after 200 kya with their classification within the "modern"/"archaic" scheme{{cn|date=January 2018}}<!--where are the references? There is no consensus on any of this, all we can do is cite individual opinions--> |

|||

{| class="wikitable" style="width:460px;" |

|||

|- |

|||

| Population |

|||

| Age |

|||

| Classification |

|||

|- |

|||

| ''[[Homo sapiens]]'' ||300 kya–present || modern |

|||

|- |

|||

| ''[[Homo sapiens sapiens]]'' ||10 kya–present || "post-glacial" modern |

|||

|- |

|||

| [[Red Deer Cave people]] || 10 kya || hybrid(?) |

|||

|- |

|||

| ''[[Homo sapiens idaltu]]'' || 200–160 kya || "early" modern |

|||

|- |

|||

|- |

|||

| [[Denisovans]]<ref name="Pääbo et al.">{{Cite journal|first=Johannes |last=Krause |first2=Qiaomei |last2=Fu |first3=Jeffrey M. |last3=Good |first4=Bence |last4=Viola |first5=Michael V. |last5=Shunkov |first6=Anatoli P. |last6=Derevianko |lastauthoramp=yes |first7=Svante |last7=Pääbo |year=2010 |title=The complete mitochondrial DNA genome of an unknown hominin from southern Siberia |journal=[[Nature (journal)|Nature]] |pmid=20336068 |volume=464 |issue=7290 |pages=894–897 |doi=10.1038/nature08976 |bibcode = 2010Natur.464..894K }}</ref> || 100–40 kya|| archaic |

|||

|- |

|||

| ''[[Homo floresiensis]]'' || 190–50 kya || archaic |

|||

|- |

|||

| ''[[Homo neanderthalensis]]'' || 250–40 kya || archaic |

|||

|- |

|||

| ''[[Homo rhodesiensis]]'' || 300–125 kya || archaic |

|||

|- |

|||

| ''[[ Homo erectus soloensis]]'' (Solo Man) ||–140 kya(?)<ref>Solo Man |

|||

was previously thought to have survived in Indonesia until about 50 kya, but |

|||

a 2011 study pushed back the date to before 140 kya. |

|||

Indriati E, Swisher CC III, Lepre C, Quinn RL, Suriyanto RA, et al. 2011 The Age of the 20 Meter Solo River Terrace, Java, Indonesia and the Survival of Homo erectus in Asia. [http://www.plosone.org/article/info%3Adoi%2F10.1371%2Fjournal.pone.0021562 PLoS ONE 6(6): e21562. ] {{doi|10.1371/journal.pone.0021562}}</ref>||archaic |

|||

|- |

|||

| ''[[Homo heidelbergensis|H. heidelbergensis]]''<ref>{{cite book|author1=Owen, Elizabeth |author2=Daintith, Eve |title=The Facts on File Dictionary of Evolutionary Biology|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=9GXdGiZyzNAC&pg=PA115|date=14 May 2014|publisher=Infobase Publishing|isbn=978-1-4381-0943-5|pages=115–}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|author1=Dawkins, Richard |author2=Wong, Yan |title=The Ancestor's Tale: A Pilgrimage to the Dawn of Evolution|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=rR9XPnaqvCMC&pg=PA63|year=2005|publisher=Houghton Mifflin Harcourt|isbn=0-618-61916-X|pages=63–}}</ref> || 600–200 kya || archaic |

|||

|- |

|||

|} |

|||

===Braincase anatomy=== |

|||

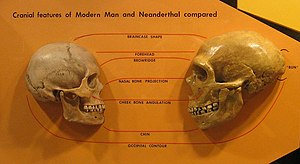

[[File:Sapiens neanderthal comparison.jpg|thumb|left|300px|Anatomical comparison of skulls of ''[[Homo sapiens]]'' (left) and ''[[Homo neanderthalensis]]'' (right)<br>(in [[Cleveland Museum of Natural History]])<br>Features compared are the [[neurocranium|braincase]] shape, [[forehead]], [[browridge]], [[nasal bone]], [[nasal bone|projection]], [[cheek bone|cheek bone angulation]], [[chin]] and [[occipital bone|occipital contour]]]] |

|||

The cranium lacks a pronounced [[occipital bun]] in the neck, a bulge that anchored considerable neck muscles in Neanderthals. Modern humans, even the earlier ones, generally have a larger fore-brain than the archaic people, so that the brain sits above rather than behind the eyes. This will usually (though not always) give a higher forehead, and reduced [[supraorbital ridge|brow ridge]]. Early modern people and some living people do however have quite pronounced brow ridges, but they differ from those of archaic forms by having both a [[supraorbital foramen]] or notch, forming a groove through the ridge above each eye.<ref>{{cite web|last=Bhupendra|first=P.|title=Forehead Anatomy|url=http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/834862-overview|work=Medscape references|accessdate=11 December 2013}}</ref> This splits the ridge into a central part and two distal parts. In current humans, often only the central section of the ridge is preserved (if it is preserved at all). This contrasts with archaic humans, where the brow ridge is pronounced and unbroken.<ref>{{cite web|title=How to ID a modern human?|url=http://www.nhm.ac.uk/about-us/news/2012/may/how-to-id-a-modern-human109960.html|work=News, 2012|publisher=[[Natural History Museum, London]]|accessdate=11 December 2013}}</ref> |

|||

Modern humans commonly have a steep, even vertical [[forehead]] whereas their predecessors had foreheads that sloped strongly backwards.<ref>{{cite encyclopedia|title=Encarta, Human Evolution |url=http://encarta.msn.com/encyclopedia_761566394_9/human_evolution.html |work= |archiveurl=https://www.webcitation.org/5kwKK5j9T?url=http://encarta.msn.com/encyclopedia_761566394_9/human_evolution.html |archivedate=31 October 2009 |deadurl=yes |df=dmy }}</ref> According to [[Desmond Morris]], the vertical forehead in humans plays an important role in human communication through [[eyebrow]] movements and forehead skin wrinkling.<ref>{{cite book|title=The Naked Woman: A Study of the Female Body|chapter=The Brow|chapterurl=https://books.google.com/books?id=Wa9zntiEKeAC&printsec=frontcover#PPA22,M1|last=Desmond Morris|authorlink=Desmond Morris|year=2007|isbn=0-312-33853-8}}</ref> |

|||

===Jaw anatomy=== |

|||

Compared to archaic people, anatomically modern humans have smaller, differently shaped teeth.<ref name="Townsend G, Richards L, Hughes T 2003 350–5">{{Cite journal|vauthors=Townsend G, Richards L, Hughes T |title=Molar intercuspal dimensions: genetic input to phenotypic variation |journal=Journal of Dental Research |volume=82 |issue=5 |pages=350–5 |date=May 2003 |pmid=12709500 |doi=10.1177/154405910308200505}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal|author=Keith A |title=Problems relating to the Teeth of the Earlier Forms of Prehistoric Man |journal=Proceedings of the Royal Society of Medicine |volume=6 |issue=Odontol Sect |pages=103–124 |year=1913 |pmid=19977113 |pmc=2005996}}</ref> |

|||

This results in a smaller, more receded dentary, making the rest of the jaw-line stand out, giving an often quite prominent chin. The central part of the mandible forming the chin carries a triangularly shaped area forming the apex of the chin called the [[mental trigon]], not found in archaic humans.<ref>{{cite book|last=Tattersall|first=Jeffrey H. Schwartz, Ian|title=The human fossil record Craniodental Morphology of Genus Homo (Africa and Asia) (vol 2)|date=2003|publisher=Wiley-Liss|location=Hoboken, NJ|isbn=0471319287|pages=327–328}}</ref> Particularly in living populations, the use of fire and tools require fewer jaw muscles, giving slender, more gracile jaws. Compared to archaic people, modern humans have smaller, lower faces. |

|||

===Body skeleton structure=== |

|||

The body skeletons of even the earliest and most robustly built modern humans were less robust than those of Neanderthals (and from what little we know from Denisovans), having essentially modern proportions. Particularly regarding the long bones of the limbs, the distal bones (the [[Radius (bone)|radius]]/[[ulna]] and [[tibia]]/[[fibula]]) are nearly the same size or slightly shorter than the proximal bones (the [[humerus]] and [[femur]]). In ancient people, particularly Neanderthals, the distal bones were shorter, usually thought to be an adaptation to cold climate.<ref>{{cite journal|last=Steegmann|first=A. Theodore|author2=Cerny, Frank J.|author3= Holliday, Trenton W.|title=Neandertal cold adaptation: Physiological and energetic factors|journal=American Journal of Human Biology|year=2002|volume=14|issue=5|pages=566–583|doi=10.1002/ajhb.10070|pmid=12203812}}</ref> The same adaptation can be found in some modern people living in the polar regions.<ref>{{cite journal|last=Stock|first=J.T.|title=Hunter-gatherer postcranial robusticity relative to patterns of mobility, climatic adaptation, and selection for tissue economy|journal=American Journal of Physical Anthropology|date=October 2006|volume=131|issue=2|pages=194–204|doi=10.1002/ajpa.20398|pmid=16596600}}</ref> |

|||

==Recent evolution== |

==Recent evolution== |

||

| Line 99: | Line 252: | ||

<ref name=Lalu>{{cite journal|last=Lalueza-Fox|title=A melanocortin-1 receptor allele suggests varying pigmentation among Neanderthals|journal=Science|year=2007|volume=318|issue=5855|pages=1453–1455|pmid=17962522|last2=Römpler|first2=H|last3=Caramelli|first3=D|last4=Stäubert|first4=C|last5=Catalano|first5=G|last6=Hughes|first6=D|last7=Rohland|first7=N|last8=Pilli|first8=E|last9=Longo|first9=L|last10=Condemi|first10=S|last11=de la Rasilla|first11=M|last12=Fortea|first12=J|last13=Rosas|first13=A|last14=Stoneking|first14=M|last15=Schöneberg|first15=T|last16=Bertranpetit|first16=J|last17=Hofreiter|first17=M|doi=10.1126/science.1147417|display-authors=etal}}</ref> |

<ref name=Lalu>{{cite journal|last=Lalueza-Fox|title=A melanocortin-1 receptor allele suggests varying pigmentation among Neanderthals|journal=Science|year=2007|volume=318|issue=5855|pages=1453–1455|pmid=17962522|last2=Römpler|first2=H|last3=Caramelli|first3=D|last4=Stäubert|first4=C|last5=Catalano|first5=G|last6=Hughes|first6=D|last7=Rohland|first7=N|last8=Pilli|first8=E|last9=Longo|first9=L|last10=Condemi|first10=S|last11=de la Rasilla|first11=M|last12=Fortea|first12=J|last13=Rosas|first13=A|last14=Stoneking|first14=M|last15=Schöneberg|first15=T|last16=Bertranpetit|first16=J|last17=Hofreiter|first17=M|doi=10.1126/science.1147417|display-authors=etal}}</ref> |

||

but the alleles for light skin in Europeans and East Asians, associated with, [[KITLG]] and [[Agouti signalling peptide|ASIP]], are (as of 2012) thought to have not been acquired by archaic admixture but recent mutations (later than 30,000 years ago).<ref name=Belezal2012>{{cite journal |url=http://mbe.oxfordjournals.org/content/early/2012/08/25/molbev.mss207.short |title=The timing of pigmentation lightening in Europeans |journal=Molecular Biology and Evolution |year=2012 |doi=10.1093/molbev/mss207 |pmid=22923467 |pmc=3525146 |volume=30 |issue=1 |pages=24–35|last2=Santos |first2=A. M. |last3=McEvoy |first3=B. |last4=Alves |first4=I. |last5=Martinho |first5=C. |last6=Cameron |first6=E. |last7=Shriver |first7=M. D. |last8=Parra |first8=E. J. |last9=Rocha |first9=J. |last1=Belezal|first1=Sandra}}</ref> |

but the alleles for light skin in Europeans and East Asians, associated with, [[KITLG]] and [[Agouti signalling peptide|ASIP]], are (as of 2012) thought to have not been acquired by archaic admixture but recent mutations (later than 30,000 years ago).<ref name=Belezal2012>{{cite journal |url=http://mbe.oxfordjournals.org/content/early/2012/08/25/molbev.mss207.short |title=The timing of pigmentation lightening in Europeans |journal=Molecular Biology and Evolution |year=2012 |doi=10.1093/molbev/mss207 |pmid=22923467 |pmc=3525146 |volume=30 |issue=1 |pages=24–35|last2=Santos |first2=A. M. |last3=McEvoy |first3=B. |last4=Alves |first4=I. |last5=Martinho |first5=C. |last6=Cameron |first6=E. |last7=Shriver |first7=M. D. |last8=Parra |first8=E. J. |last9=Rocha |first9=J. |last1=Belezal|first1=Sandra}}</ref> |

||

==Behavioral modernity== |

|||

[[Behavioral modernity]], involving the development of [[origin of language|language]], [[Paleolithic Art|figurative art]] and early forms of [[Paleolithic religion|religion]] (etc.) is taken to have arisen before 40,000 years ago, marking the beginning of the [[Upper Paleolithic]] (in African contexts also known as the [[Later Stone Age]]).<ref name="Klein 1995">{{cite journal |last=Klein |first=Richard |title=Anatomy, behavior, and modern human origins |journal=Journal of World Prehistory |date=1995 |volume=9 |issue=2 |pages=167–198 |doi=10.1007/bf02221838}}</ref> |

|||

There is considerable debate regarding whether the earliest anatomically modern humans behaved similarly to recent or existing humans. |

|||

[[Behavioral modernity]] is taken to include fully developed [[Origin of language|language]] (requiring the capacity for [[abstract thought]]), [[Art of the Upper Paleolithic|artistic expression]], early forms of [[Paleolithic religion|religious behavior]],<ref>{{cite book|author=Feierman, Jay R. |page=220|title=The Biology of Religious Behavior: The Evolutionary Origins of Faith and Religion|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=mOLGXhzAXhsC|year=2009|publisher=ABC-CLIO|isbn=978-0-313-36430-3}}</ref> increased cooperation and the formation of early settlements, and the production of articulated tools from [[Lithic core|lithic cores]], bone or antler. |

|||

The term [[Upper Paleolithic]] is intended to cover the period since the [[Coastal migration|rapid expansion]] of modern humans throughout Eurasia, which coincides with the first appearance of [[Paleolithic art]] such as [[cave paintings]] and the development of technological innovation such as the [[spear-thrower]]. The Upper Paleolithic begins around 50,000 to 40,000 years ago, and also coincides with the disappearance of archaic humans such as the |

|||

[[Neanderthal]]s. |

|||

The term "behavioral modernity" is somewhat disputed. It is most often used for the set of characteristics marking the Upper Paleolithic, but |

|||

some scholars use "behavioral modernity" for the emergence of ''H. sapiens'' around 200,000 years ago,<ref>Soressi M. (2005) [http://www.eva.mpg.de/evolution/staff/soressi/pdf/Soressi2005_ToolsToSymbols.pdf Late Mousterian lithic technology. Its implications for the pace of the emergence of behavioural modernity and the relationship between behavioural modernity and biological modernity], pp. 389–417 in L. Backwell et F. d’Errico (eds.) ''From Tools to Symbols'', Johanesburg: University of Witswatersand Press. {{ISBN|1868144178}}.</ref> while others use the term for the rapid developments occurring around 50,000 years ago.<ref>''Companion encyclopedia of archaeology'' (1999). Routledge. {{ISBN|0415213304}}. Vol. 2. p. 763 (''cf''., ... "effectively limited to [[Organic matter|organic samples]]" [ed. [[organic compound]]s ] "or [[biogenic|biogenic carbonate]]s that date to less than 50 ka (50,000 years ago)."). See also: [[Later Stone Age]] and [[Upper Paleolithic]].</ref><ref name="mellars">{{cite journal|authorlink=Paul Mellars|last=Mellars |first=Paul|title=Why did modern human populations disperse from Africa ca. 60,000 years ago?|year=2006|doi=10.1073/pnas.0510792103|journal=Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences|volume=103|pages=9381–6|pmid=16772383|issue=25|pmc=1480416|bibcode=2006PNAS..103.9381M}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal|last1=Shea|first1=John|title=Homo sapiens Is As Homo sapiens Was|journal=Current Anthropology|date=2011|volume=52|issue=1|pages=1–35|doi=10.1086/658067}}</ref> It has that the emergence of behavioral modernity was a gradual process.<ref>{{cite journal|last1=McBrearty|first1=Sally|last2=Brooks|first2=Allison|date=2000|title=The revolution that wasn't: a new interpretation of the origin of modern human behavior|journal=Journal of Human Evolution|volume=39|issue=5|pages=453–563|doi=10.1006/jhev.2000.0435|pmid=11102266}} |

|||

{{cite journal|last1=Henshilwood|first1=Christopher|last2=Marean|first2=Curtis|date=2003|title=The Origin of Modern Human Behavior: Critique of the Models and Their Test Implications|journal=Current Anthropology|volume=44|issue=5|pages=627–651|doi=10.1086/377665}} |

|||

{{cite journal|last1=Marean|first1=Curtis|title=Early human use of marine resources and pigment in South Africa during the Middle Pleistocene|journal=Nature|date=2007|volume=449|issue=7164|display-authors=etal|doi=10.1038/nature06204|pages=905–908|pmid=17943129|bibcode=2007Natur.449..905M}} |

|||

{{cite journal|last1=Powell|first1=Adam|title=Late Pleistocene Demography and the Appearance of Modern Human Behavior|journal=Science|date=2009|volume=324|issue=5932|pages=1298–1301|display-authors=etal|doi=10.1126/science.1170165|bibcode=2009Sci...324.1298P|pmid=19498164}} |

|||

{{cite journal|last1=Premo|first1=Luke|last2=Kuhn|first2=Steve|title=Modeling Effects of Local Extinctions on Culture Change and Diversity in the Paleolithic|journal=PLoS ONE|date=2010|volume=5|issue=12|doi=10.1371/journal.pone.0015582|pmid=21179418|pages=e15582|bibcode=2010PLoSO...515582P|pmc=3003693}}</ref> |

|||

In January 2018 it was announced that modern human finds at Misliya cave, Israel, in 2002, had been dated to around 185,000 years ago, the earliest evidence of their out of Africa migration.<ref>{{Cite news|url=https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2018/01/180125140923.htm|title=Scientists discover oldest known modern human fossil outside of Africa: Analysis of fossil suggests Homo sapiens left Africa at least 50,000 years earlier than previously thought|work=ScienceDaily|access-date=2018-01-28|language=en}}</ref><ref>{{Cite news|url=http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/science-environment-42817323|title=Modern humans left Africa much earlier|last=Ghosh|first=Pallab|date=2018|work=BBC News|access-date=2018-01-28|language=en-GB}}</ref><ref>{{Cite news|url=https://www.timesofisrael.com/jawbone-fossil-found-in-israeli-cave-resets-clock-for-modern-human-evolution/|title=Jawbone fossil found in Israeli cave resets clock for modern human evolution|access-date=2018-01-28|language=en-US}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.theguardian.com/science/2018/jan/25/oldest-known-human-fossil-outside-africa-discovered-in-israel|title=Oldest known human fossil outside Africa discovered in Israel|last=Devlin|first=Hannah|date=2018-01-25|website=the Guardian|language=en|access-date=2018-01-28}}</ref> |

|||

The earliest ''H. sapiens'' (AMH) found in [[Paleolithic Europe|Europe]] are the "[[Cro-Magnon]]" (named after the site of first discovery in France), beginning about 40,000 to 35,000 years ago. These are also known as "[[European early modern humans]]" in contrast to the preceding [[Neanderthals]].<ref name="Brace">{{cite journal|last=Brace|first=C. Loring|editor1-first=Alice M.|editor1-last=Haeussler|editor2-first=Shara E.|editor2-last=Bailey|year=1996|title=Cro-Magnon and Qafzeh — vive la Difference|journal=Dental anthropology newsletter: a publication of the Dental Anthropology Association|volume=10|issue=3|pages=2–9|publisher=Laboratory of Dental Anthropology, Department of Anthropology, Arizona State University|location=Tempe, AZ|issn=1096-9411|oclc=34148636|url=http://anthropology.osu.edu/DAA/back%20issues/DA_10_03.pdf#page=2|format=PDF|accessdate=31 March 2010|deadurl=yes|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20100622130544/http://anthropology.osu.edu/DAA/back%20issues/DA_10_03.pdf#page=2|archivedate=22 June 2010|df=dmy-all}}</ref><ref name=Fagan>{{cite book|last=Fagan|first=B.M.|title=The Oxford Companion to Archaeology|year=1996|publisher=Oxford University Press|location=Oxford, UK|isbn=978-0-19-507618-9|page=864}}</ref> |

|||

The equivalent of the Eurasian Upper Paleolithic in African archaeology is known as the [[Later Stone Age]], also beginning roughly 40,000 years ago. |

|||

While most clear evidence for behavioral modernity uncovered from the later 19th century was from Europe, such as the [[Venus figurine]]s and other artefacts from the [[Aurignacian]], more recent archaeological research has shown that all essential elements of the kind of material culture typical of contemporary [[San people|San]] hunter-gatherers in [[Southern Africa]] was also present by least 40,000 years ago, including digging sticks of similar materials used today, [[Common ostrich|ostrich]] egg shell beads, bone [[arrow]] heads with individual maker's marks etched and embedded with red ochre, and poison applicators.<ref>{{Cite journal |doi= 10.1073/pnas.1204213109|title= Early evidence of San material culture represented by organic artifacts from Border Cave, South Africa|journal= Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences|volume= 109|issue= 33|pages= 13214|year= 2012|last1= d'Errico|first1= F.|last2= Backwell|first2= L.|last3= Villa|first3= P.|last4= Degano|first4= I.|last5= Lucejko|first5= J. J.|last6= Bamford|first6= M. K.|last7= Higham|first7= T. F. G.|last8= Colombini|first8= M. P.|last9= Beaumont|first9= P. B.|bibcode= 2012PNAS..10913214D}}</ref> There is also a suggestion that "pressure flaking best explains the morphology of lithic artifacts recovered from the c. 75-ka Middle Stone Age levels at Blombos Cave, South Africa. The technique was used during the final shaping of Still Bay bifacial points made on heat‐treated silcrete."<ref>{{Cite journal |doi=10.1126/science.1195550|pmid=21030655|title=Early Use of Pressure Flaking on Lithic Artifacts at Blombos Cave, South Africa|journal=Science|volume=330|issue=6004|pages=659|year=2010|last1=Mourre|first1=V.|last2=Villa|first2=P.|last3=Henshilwood|first3=C. S.|bibcode=2010Sci...330..659M}}</ref> |

|||

Both pressure flaking and heat treatment of materials were previously thought to have occurred much later in prehistory, and both indicate a behaviourally modern sophistication in the use of natural materials. Further reports of research on cave sites along the southern African coast indicate that "the debate as to when cultural and cognitive characteristics typical of modern humans first appeared" may be coming to an end, as "advanced technologies with elaborate chains of production" which "often demand high-fidelity transmission and thus language" have been found at Pinnacle Point Site 5–6. These have been dated to approximately 71,000 years ago. The researchers suggest that their research "shows that microlithic technology originated early in South Africa, evolved over a vast time span (c. 11,000 years), and was typically coupled to complex heat treatment that persisted for nearly 100,000 years. Advanced technologies in [[Africa]] were early and enduring; a small sample of excavated sites in Africa is the best explanation for any perceived 'flickering' pattern."<ref>{{cite journal |doi=10.1038/nature11660|pmid=23135405|title=An early and enduring advanced technology originating 71,000 years ago in South Africa|journal=Nature|volume=491|issue=7425|pages=590|year=2012|last1=Brown|first1=Kyle S.|last2=Marean|first2=Curtis W.|last3=Jacobs|first3=Zenobia|last4=Schoville|first4=Benjamin J.|last5=Oestmo|first5=Simen|last6=Fisher|first6=Erich C.|last7=Bernatchez|first7=Jocelyn|last8=Karkanas|first8=Panagiotis|last9=Matthews|first9=Thalassa|bibcode=2012Natur.491..590B}}</ref> |

|||

These results suggest that Late Stone Age foragers in Sub-Saharan Africa had developed modern cognition and behaviour by at least 50,000 years ago.<ref name="onlinelibrary.wiley.com">{{cite journal |doi=10.1002/ajpa.21011|pmid=19226648|title=Human DNA sequences: More variation and less race|journal=American Journal of Physical Anthropology|volume=139|issue=1|pages=23–34|year=2009|last1=Long|first1=Jeffrey C.|last2=Li|first2=Jie|last3=Healy|first3=Meghan E.}}</ref> |

|||

The change in behavior has been speculated to have been a consequence of an earlier climatic change to much drier and colder conditions between 135,000 and 75,000 years ago.<ref>{{cite journal |doi= 10.1073/pnas.0703874104|title= East African megadroughts between 135 and 75 thousand years ago and bearing on early-modern human origins|journal= Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences|volume= 104|issue= 42|pages= 16416|year= 2007|last1= Scholz|first1= C. A.|last2= Johnson|first2= T. C.|last3= Cohen|first3= A. S.|last4= King|first4= J. W.|last5= Peck|first5= J. A.|last6= Overpeck|first6= J. T.|last7= Talbot|first7= M. R.|last8= Brown|first8= E. T.|last9= Kalindekafe|first9= L.|last10= Amoako|first10= P. Y. O.|last11= Lyons|first11= R. P.|last12= Shanahan|first12= T. M.|last13= Castaneda|first13= I. S.|last14= Heil|first14= C. W.|last15= Forman|first15= S. L.|last16= McHargue|first16= L. R.|last17= Beuning|first17= K. R.|last18= Gomez|first18= J.|last19= Pierson|first19= J.|bibcode= 2007PNAS..10416416S|pmid=17785420|pmc=1964544}}</ref> |

|||

This might have led to human groups who were seeking refuge from the inland droughts, expanded along the coastal marshes rich in shellfish and other resources. Since sea levels were low due to so much water tied up in [[Glacier|glaciers]], such marshlands would have occurred all along the southern coasts of Eurasia. The use of [[Raft|rafts]] and boats may well have facilitated exploration of offshore islands and travel along the coast, and eventually permitted expansion to New Guinea and then to [[Australia]].<ref>{{cite book|title=The Journey of Man: A Genetic Odyssey|author=Wells, Spencer |url=http://press.princeton.edu/titles/7442.html|isbn=9780691115320|year=2003}}</ref> |

|||

== References == |

== References == |

||

| Line 105: | Line 284: | ||

== External links == |

== External links == |

||

{{Commons category|Homo sapiens|''Homo sapiens''}} |

{{Commons category|Homo sapiens|''Homo sapiens''}} |

||

{{wikispecies|Homo sapiens}} |

|||

* [http://humanorigins.si.edu/evidence/human-evolution-timeline-interactive Human Timeline (Interactive)] – [[Smithsonian Institution|Smithsonian]], [[National Museum of Natural History]] (August 2016). |

* [http://humanorigins.si.edu/evidence/human-evolution-timeline-interactive Human Timeline (Interactive)] – [[Smithsonian Institution|Smithsonian]], [[National Museum of Natural History]] (August 2016). |

||

{{Human Evolution|state=uncollapsed}} |

{{Human Evolution|state=uncollapsed}} |

||

{{Big History}} |

{{Big History}} |

||

{{portal bar|Anthropology|Evolutionary biology |

{{portal bar|Anthropology|Evolutionary biology}} |

||

{{Taxonbar|from=Q15978631}} |

{{Taxonbar|from=Q15978631}} |

||

Revision as of 10:10, 21 April 2018

| Early modern human Temporal range: Middle Pleistocene–Present

| |

|---|---|

| |

| Male and female H s. sapiens (Akha in northern Thailand, 2010 photograph) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Primates |

| Suborder: | Haplorhini |

| Infraorder: | Simiiformes |

| Family: | Hominidae |

| Subfamily: | Homininae |

| Tribe: | Hominini |

| Genus: | Homo |

| Species: | H. sapiens

|

| Binomial name | |

| Homo sapiens Linnaeus, 1758

| |

| Subspecies | |

|

H. s. sapiens | |

Homo sapiens is the systematic name used in taxonomy (also known as binomial nomenclature) for anatomically modern humans, i.e. the only extant human species. The name is Latin for "wise man" and was introduced in 1758 by Carl Linnaeus (who is himself also the type specimen).

Extinct species of the genus Homo are classified as "archaic humans". This includes at least the separate species Homo erectus, and possibly a number of other species (which are variously also considered subspecies of either H. sapiens or H. erectus). H. sapiens idaltu (2003) is a proposed extinct subspecies of H. sapiens.

The age of speciation of H. sapiens out of ancestral H. erectus (or an intermediate species such as Homo heidelbergensis) is estimated to have taken place at roughly 300,000 years ago. Sustained archaic admixture is known to have taken place both in Africa and (following the recent Out-Of-Africa expansion) in Eurasia, between about 100,000 to 30,000 years ago.

In certain contexts, the term anatomically modern humans[2] (AMH) is used to distinguish H. sapiens as having an anatomy consistent with the range of phenotypes seen in contemporary humans from varieties of extinct archaic humans. This is useful especially for times and regions where anatomically modern and archaic humans co-existed, e.g. in Paleolithic Europe.

Name and taxonomy

The binomial name Homo sapiens was coined by Carl Linnaeus (1758).[3] The Latin noun homō (genitive hominis) means "human being." The species is taken to have emerged from a predecessor within the Homo genus around 200,000 to 300,000 years ago.[4]

Extant human populations have historically been divided into subspecies, but since c. the 1980s all extant groups tend to be subsumed into a single species, H. sapiens, avoiding division into subspecies altogether.[5]

Some sources show Neanderthals (Homo neanderthalensis) as a subspecies (Homo sapiens neanderthalensis).[6][7] Similarly, the discovered specimens of the Homo rhodesiensis species have been classified by some as a subspecies (Homo sapiens rhodesiensis), although it remains more common to treat these last two as separate species within the genus Homo rather than as subspecies within H. sapiens.[8]

Age and speciation process

Derivation from H. erectus

The speciation of H. sapiens out of varieties of H. erectus is estimated as having taken place between 300,000 and 200,000 years ago.

The derivation of a comparatively homogeneous single species of Homo sapiens from more diverse varieties of archaic humans (all of which were descended from the dispersal of Homo erectus some 1.8 million years ago) was debated in terms of two competing models during the 1980s: "recent African origin" postulated the emergence of Homo sapiens from a single source population in Africa, which expanded and led to the extinction of all other human varieties, while the "multiregional evolution" model postulated the survival of regional forms of archaic humans, gradually converging into the modern human varieties by the mechanism of clinal variation, via genetic drift, gene flow and selection throughout the Pleistocene.[11]

Since the 2000s, the availability of date from archaeogenetics and population genetics has led to the emergence of a much more detailed picture, intermediate between the two competing scenarios outlined above: The recent Out-of-Africa expansion accounts for the predominant part of modern human ancestry, while there were also significant admixture events with regional archaic humans.[12]

Since the 1970s, the Omo remains, dated to some 195,000 years ago, have often been taken as the conventional cut-off point for the emergence of "anatomically modern humans". Since the 2000s, the discovery of older remains with comparable characteristics, and the discovery of ongoing hybridization between "modern" and "archaic" populations after the time of the Omo remains, have opened up a renewed debate on the "age of Homo sapiens",

in journalistic publications cast into terms of "Homo sapiens may be older than previously thought".[13]

Homo sapiens idaltu, dated to 160,000 years ago, has been postulated as an extinct subspecies of Homo sapiens in 2003.[14] Homo neanderthalensis, which became extinct 30,000 years ago, has also been classified as a subspecies, Homo sapiens neanderthalensis; genetic studies now suggest that the functional DNA of modern humans and Neanderthals diverged 500,000 years ago.[15]

Early Homo sapiens

The term Middle Paleolithic is intended to cover the time between the first emergence of Homo sapiens (roughly 300,000 years ago) and the emergence of full behavioral modernity (roughly 50,000 years ago).

Many of the early modern human finds, like those of Omo, Herto, Skhul, and Peștera cu Oase exhibit a mix of archaic and modern traits.[16][17] Skhul V, for example, has prominent brow ridges and a projecting face. However, the brain case is quite rounded and distinct from that of the Neanderthals and is similar to the brain case of modern humans. It is now known that modern humans north of Sahara and outside of Africa have some archaic human admixture, though whether the robust traits of some of the early modern humans like Skhul V reflects mixed ancestry or retention of older traits is uncertain.[18][19]

The "gracile" or lightly built skeleton of anatomically modern humans has been connected to a change in behavior, including increased cooperation and "resource transport".[20]

There is evidence that the characteristic human brain development, especially the prefrontal cortex, was due to "an exceptional acceleration of metabolome evolution ... paralleled by a drastic reduction in muscle strength. The observed rapid metabolic changes in brain and muscle, together with the unique human cognitive skills and low muscle performance, might reflect parallel mechanisms in human evolution."[21] The Schöningen spears and their correlation of finds are evidence of complex technological skills already 300,000 years ago and are the first obvious proof for an active (big game) hunt. H. heidelbergensis already had intellectual and cognitive skills like anticipatory planning, thinking and acting that so far have only been attributed to modern man.[22][23]

The ongoing admixture events within anatomically modern human populations make it difficult to give an estimate on the age of the matrilinear and patrilinear most recent common ancestors of modern populations (Mitochondrial Eve and Y-chromosomal Adam). Estimates on the age of Y-chromosomal Adam have been pushed back significantly with the discovery of an ancient Y-chromosomal lineage in 2013, likely beyond 300,000 years ago.[24] There has, however, been no reports of the survival of Y-chromosomal or mitochondrial DNA clearly deriving from archaic humans (which would push back the age of the most recent patrilinear or matrilinear ancestor beyond 500,000 years).[25]

Dispersal and archaic admixture

Dispersal of early H. sapiens begins soon after its emergence.

The Khoi-San of Southern Africa may be the human population with the deepest temporal division from all other contemporary populations, estimated at close to 130,000 years ago. A 2011 study has classified them as an "ancestral population cluster". The same study also located the origin of the first wave of expansion of H. sapiens, beginning roughly 130,000 years ago, in southwestern Africa, near the coastal border of Namibia and Angola.[26] A 2017 analysis suggested that the Khoi-San diverged from West African populations even earlier, between 260,000 and 350,000 years ago, compatible with (an upper limit of) the age of H. sapiens.[27] Homo sapiens idaltu, found at site Middle Awash in Ethiopia, lived about 160,000 years ago.[28] The discovery of fossils attributed to H. sapiens, along with stone tools, dated to approximately 300,000 years ago, found at Jebel Irhoud, Morocco was announced in 2017.[29]

Early H. sapiens may have reached Asia in a first wave as early as 120,000 years ago.[30][31][32] Evidence presented in 2017 raises the possibility that a yet earlier migration, dated to around 270,000 years ago, may have left traces of admixture in Neanderthal genome.[33]

The Recent "Out of Africa" migration of Homo sapiens took place in at least two waves, the first around 130,000 to 100,000 years ago, the second (Southern Dispersal) around 70,000 to 60,000 years ago, resulting in the colonization of Australia around 65,000 years ago,[34] while Europe was populated by an early offshoot which settled the Near East and Europe by around 50,000 years ago.

Evidence for the overwhelming contribution of the "recent African origin" of modern populations outside of Africa was established based on mitochondrial DNA, combined with evidence based on physical anthropology of archaic specimens, during the 1990s and 2000s.[35] The assumption of complete replacement has been revised in the 2010s with the discovery admixture events (introgression) of populations of H. sapiens with populations of archaic humans over the period of between roughly 100,000 and 30,000 years ago, both in Eurasia and in Sub-Saharan Africa. The extent of Neanderthal admixture (and introgression of genes acquired by admixture) varies significantly between contemporary racial groups, being absent in Africans, intermediate in Europeans and highest in East Asians. Certain genes related to UV-light adaptation introgressed from Neanderthals have been found to have been selected for in East Asians specifically from 45,000 years ago until around 5,000 years ago.[36] The extent of archaic admixture is of the order of about 1% to 4% in Europeans and East Asians, and highest among Melanesians (Denisova hominin admixture), at 4% to 6%.[37] Cumulatively, about 20% of the Neanderthal genome is estimated to remain present in contemporary populations.[38]

Anatomy

Generally, modern humans are more lightly built than archaic humans from which they have evolved. Humans are a highly variable species; modern humans can show remarkably robust traits, and early modern humans even more so. Despite this, modern humans differ from archaic people (the Neanderthals and Denisovans) in a range of anatomical details.

Anatomical modernity

The term "anatomically modern humans" (AMH) is used with varying scope depending on context, to distinguish "anatomically modern" Homo sapiens from archaic humans such as Neanderthals. In a convention popular in the 1990s, Neanderthals were classified as a subspecies of H. sapiens, as H. s. neanderthalensis, while AMH (or European early modern humans, EEMH) was taken to refer to "Cro-Magnon" or H. s. sapiens. Under this nomenclature (Neanderthals considered H. sapiens), the term "anatomically modern Homo sapiens" (AMHS) has also been used to refer to EEMH ("Cro-Magnons").[39] It has since become more common to designate Neanderthals as a separate species, H. neanderthalensis, so that AMH in the European context refers to H. sapiens (but the question is by no means resolved[40]).

In this more narrow definition of Homo sapiens, the subspecies H. s. idaltu, discovered in 2003, also falls under the umbrella of "anatomically modern".[41] The recognition of Homo sapiens idaltu as a valid subspecies of the anatomically modern human lineage would justify the description of contemporary humans with the subspecies name Homo sapiens sapiens.

A further division of AMH into "early" or "robust" vs. "post-glacial" or "gracile" subtypes has since been used for convenience. The emergence of "gracile AMH" is taken to reflect a process towards a smaller and more fine-boned skeleton beginning around 50,000–30,000 years ago.[42]

The following is a list of human varieties which lived after 200 kya with their classification within the "modern"/"archaic" scheme[citation needed]

| Population | Age | Classification |

| Homo sapiens | 300 kya–present | modern |

| Homo sapiens sapiens | 10 kya–present | "post-glacial" modern |

| Red Deer Cave people | 10 kya | hybrid(?) |

| Homo sapiens idaltu | 200–160 kya | "early" modern |

| Denisovans[43] | 100–40 kya | archaic |

| Homo floresiensis | 190–50 kya | archaic |

| Homo neanderthalensis | 250–40 kya | archaic |

| Homo rhodesiensis | 300–125 kya | archaic |

| Homo erectus soloensis (Solo Man) | –140 kya(?)[44] | archaic |

| H. heidelbergensis[45][46] | 600–200 kya | archaic |

Braincase anatomy

(in Cleveland Museum of Natural History)

Features compared are the braincase shape, forehead, browridge, nasal bone, projection, cheek bone angulation, chin and occipital contour

The cranium lacks a pronounced occipital bun in the neck, a bulge that anchored considerable neck muscles in Neanderthals. Modern humans, even the earlier ones, generally have a larger fore-brain than the archaic people, so that the brain sits above rather than behind the eyes. This will usually (though not always) give a higher forehead, and reduced brow ridge. Early modern people and some living people do however have quite pronounced brow ridges, but they differ from those of archaic forms by having both a supraorbital foramen or notch, forming a groove through the ridge above each eye.[47] This splits the ridge into a central part and two distal parts. In current humans, often only the central section of the ridge is preserved (if it is preserved at all). This contrasts with archaic humans, where the brow ridge is pronounced and unbroken.[48]

Modern humans commonly have a steep, even vertical forehead whereas their predecessors had foreheads that sloped strongly backwards.[49] According to Desmond Morris, the vertical forehead in humans plays an important role in human communication through eyebrow movements and forehead skin wrinkling.[50]

Jaw anatomy

Compared to archaic people, anatomically modern humans have smaller, differently shaped teeth.[51][52] This results in a smaller, more receded dentary, making the rest of the jaw-line stand out, giving an often quite prominent chin. The central part of the mandible forming the chin carries a triangularly shaped area forming the apex of the chin called the mental trigon, not found in archaic humans.[53] Particularly in living populations, the use of fire and tools require fewer jaw muscles, giving slender, more gracile jaws. Compared to archaic people, modern humans have smaller, lower faces.

Body skeleton structure

The body skeletons of even the earliest and most robustly built modern humans were less robust than those of Neanderthals (and from what little we know from Denisovans), having essentially modern proportions. Particularly regarding the long bones of the limbs, the distal bones (the radius/ulna and tibia/fibula) are nearly the same size or slightly shorter than the proximal bones (the humerus and femur). In ancient people, particularly Neanderthals, the distal bones were shorter, usually thought to be an adaptation to cold climate.[54] The same adaptation can be found in some modern people living in the polar regions.[55]

Recent evolution

Following the second Out-of-Africa expansion, some 70,000 to 50,000 years ago, some subpopulations of H. sapiens have been essentially isolated for tens of thousands of years prior to the early modern Age of Discovery.

Combined with archaic admixture this has resulted in significant genetic variation, which in some instances has been shown to be the result of directional selection taking place over the past 15,000 years, i.e. significantly later than possible archaic admixture events.[56]

Some climatic adaptations, such as high-altitude adaptation in humans, are thought to have been acquired by archaic admixture. Inuit adaptation to high-fat diet and cold climate has been traced to a mutation dated the Last Glacial Maximum (20,000 years ago).[57] Adaptations related to agriculture and animal domestication, such as the East Asian types of ADH1B associated with rice domestication,[58] or lactase persistence,[59] are due to recent selection pressures. Similarly, adaptations in spleen size and pupil-controlling muscles which enhance underwater sight in the Austronesian Sama-Bajau have developed under selection pressures associated with subsisting on freediving over the past thousand years or so.[60]

Physiological or phenotypical changes have also been traced to recent (Upper Paleolithic) mutations, such as the East Asian variant of the EDAR gene, dated to c. 35,000 years ago.[61] Alleles predictive of light skin have been found in Neanderthals, [62] but the alleles for light skin in Europeans and East Asians, associated with, KITLG and ASIP, are (as of 2012) thought to have not been acquired by archaic admixture but recent mutations (later than 30,000 years ago).[63]

Behavioral modernity

Behavioral modernity, involving the development of language, figurative art and early forms of religion (etc.) is taken to have arisen before 40,000 years ago, marking the beginning of the Upper Paleolithic (in African contexts also known as the Later Stone Age).[64]