1964 Pacific typhoon season: Difference between revisions

TheAustinMan (talk | contribs) →Season summary: Expand season summary section |

TheAustinMan (talk | contribs) →Systems: Expand Tess/Viola. Remove sections for TDs (they'll be moved to an other storms section and/or a season table) |

||

| Line 160: | Line 160: | ||

{{clear}} |

{{clear}} |

||

==Systems== |

== Systems == |

||

===Typhoon Tess (Asiang)=== |

=== Typhoon Tess (Asiang) === |

||

{| class="wikitable floatleft" |

|||

|+ Peak intensity estimates<ref name="IBTrACS_Tess" /> |

|||

! Agency |

|||

! Wind<br />(kt){{efn|The Joint Typhoon Warning Center (JTWC) estimates the [[maximum sustained wind]] of a tropical cyclone has the highest windspeed averaged over one minute, the China Meteorological Administration (CMA) averages such winds over two minutes, and the Hong Kong Observatory (HKO) and Japan Meteorological Agency (JMA) averages such winds over ten minutes in their historical records.<ref name="Ying et al." />|name=MSW}} |

|||

! Pressure<br />(hPa) |

|||

|- |

|||

! CMA |

|||

| 97 || 966 |

|||

|- |

|||

! HKO |

|||

| 75 || 965 |

|||

|- |

|||

! JMA |

|||

| {{N/a}} || 960 |

|||

|- |

|||

! JTWC |

|||

| 85 || {{N/a}} |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

{{Infobox Hurricane Small |

{{Infobox Hurricane Small |

||

|Basin=WPac |

|Basin=WPac |

||

| Line 167: | Line 185: | ||

|Track=Tess 1964 track.png |

|Track=Tess 1964 track.png |

||

|Formed=May 12 |

|Formed=May 12 |

||

|Dissipated=May 27{{efn|Storm durations and intensities are based on the International Best Track Archive for Climate Stewardship (IBTrACS), which is endorsed by the [[World Meteorological Organization]]'s Tropical Cyclone Programme as "an official archiving and distribution resource for tropical cyclone best track data." However, different meteorological agencies, including the JTWC, [[Japan Meteorological Agency]], [[China Meteorological Administration]], and [[Hong Kong Observatory]] have disparate datasets for tropical cyclone histories that may not precisely reflect the storm attributes listed here.|name=IBTrACS}} |

|||

|Dissipated=May 23 |

|||

|Type1= |

|Type1= |

||

|Type2=cat2 |

|Type2=cat2 |

||

|1-min winds=85 |

|1-min winds=85 |

||

|Pressure=960 |

|Pressure=960 |

||

}} |

}} |

||

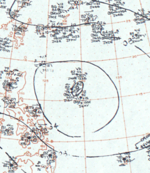

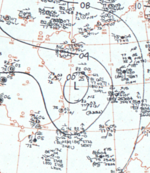

The first tropical cyclone of the season was initially identified by the [[Joint Typhoon Warning Center]] (JTWC) on May 9 near [[Woleai Atoll]]. Tracking steadily west-northwestward, the system gradually organized. Early on May 14, the system had become sufficiently organized for the JTWC to classify it as a tropical depression.<ref name="01W"/> Over the following four days, the depression moved erratically, executing two loops, and fluctuated between tropical storm and tropical depression status.<ref name="01WBT">{{cite web|author=Joint Typhoon Warning Center|publisher=United States Navy|year=1965|accessdate=March 11, 2010|title=Typhoon 01W (Tess) Best Track|url=http://www.usno.navy.mil/NOOC/nmfc-ph/RSS/jtwc/best_tracks/1964/1964s-bwp/bwp011964.txt}}</ref> During the morning of May 15, the system had intensified into a tropical storm and was given the name Tess. The developing storm eventually retained an east-northeastward track by May 18. The following day, reconnaissance aircraft recording data on the storm discovered that it had developed two [[Eye (cyclone)|eyes]]. The first and innermost eye was unusually small, measuring {{convert|6|mi|km|abbr=on}} across while the second was asymmetrical, measuring roughly {{convert|14|mi|km|abbr=on}} by {{convert|9|mi|km|abbr=on}}. Upon finding this feature, Tess was estimated to have attained typhoon status. Gradual intensification took place over the following few days as the storm turned more northeasterly.<ref name="01W"/> On May 22, Tess attained its peak intensity with winds of 155 km/h (100 mph) and a [[barometric pressure]] of 960 [[Bar (unit)|mbar]] ([[Pascal (unit)|hPa]]).<ref name="01W"/><ref name="01WBT"/> However, by this point the typhoon was moving over higher latitudes and into a less favorable environment. The following day, Tess had significantly weakened to a tropical storm and the center of the storm became exposed. Later on May 23 the typhoon became [[extratropical cyclone|extratropical]] as it moved over the north Pacific.<ref name="01W">{{cite web|author=Joint Typhoon Warning Center|publisher=United States Navy|year=1965|accessdate=March 11, 2010|title=Typhoon Tess Summary|url=http://www.usno.navy.mil/NOOC/nmfc-ph/RSS/jtwc/atcr/1964atcr/pdf/wnp/01.pdf|format=[[PDF]]|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110606234054/http://www.usno.navy.mil/NOOC/nmfc-ph/RSS/jtwc/atcr/1964atcr/pdf/wnp/01.pdf|archive-date=2011-06-06|url-status=dead}}</ref> |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

The first [[tropical cyclone]] of 1964 developed from a segment of the polar [[trough (meteorology)|trough]]. A wind circulation was first identified near [[Woleai]] by the JTWC on May 9. This initial disturbance traveled west-northwest, passing near [[Ulithi]] and [[Yap]].<ref name="ATR" />{{rp|72}} On May 14, it organized further into a [[tropical depression]] and took an erratic track over the next four days, including a looping course.<ref name="IBTrACS_Tess">{{cite web |title=1964 Typhoon TESS (1964133N10134) |website=IBTrACS - International Best Track Archive for Climate Stewardship|url=http://www.atms.unca.edu/ibtracs/ibtracs_v04r00/index.php?name=v04r00-1964133N10134 |publisher=University of North Carolina–Asheville |accessdate=June 12, 2020 |location=Asheville, North Carolina |date=2018}}</ref><ref name="ATR" />{{rp|50,74}} During this process, it strengthened into a [[tropical storm]], weakened to a tropical depression, and reattained tropical storm intensity before heading on an east-northwestward to northeastward trajectory.<ref name="IBTrACS_Tess" /><ref name="CD_Annual" />{{rp|74}} On May 19, a reconnaissance flight investigating Tess observed two [[eye (cyclone)|eye]]s: the first and innermost eye measured 9.7 km (6 mi) across while the second was asymmetrical, with axes roughly 23 km (14 mi) and 14 km (9 mi) across.<ref name="ATR" />{{rp|75}} Shortly after finding this feature, Tess was estimated to have attained typhoon status.<ref name="IBTrACS_Tess" /> |

|||

===Tropical Depression 02W=== |

|||

{{Infobox Hurricane Small |

|||

Tess tracked towards the northeast after reaching typhoon intensity. Its center passed between [[Alamagan]] and [[Guguan]] on May 20 while [[maximum sustained wind]]s in the typhoon were 140 km/h (85 mph).<ref name="IBTrACS_Tess" /> Farther southeast, in [[Guam]], the passing storm produced 52 mm (2.03 in) of rain.<ref name="GuamTCs">{{cite report|last1=Weir |first1=Robert C. |title=Tropical Cyclones Affecting Guam (1671–1980) |url=https://apps.dtic.mil/dtic/tr/fulltext/u2/a134016.pdf |publisher=Joint Typhoon Warning Center |accessdate=June 12, 2020 |location=San Francisco, California |format=PDF |date=October 25, 1983}}</ref> The next day, Tess reached its peak intensity with winds of 155 km/h (100 mph) and a minimum [[barometric pressure]] of 960 [[pascal (unit)|hPa]] ([[bar (unit)|mbar]]; 28.35 [[inches of mercury|inHg]]).<ref name="IBTrACS_Tess" /> A [[seabee]] stationed on the island was presumed to have drowned after being swept away by the rough seas generated by the storm; two landing crafts were also destroyed by the rough seas.<ref name="TexasManBelievedDrowned">{{cite news |title=Texas Man Believed Drowned in Typhon |url=https://www.newspapers.com/clip/53324278/|via=Newspapers.com |accessdate=June 12, 2020 |work=Shreveport Journal |agency=Associated Press |issue=|volume=70 |date=May 23, 1964 |location=Shreveport, Louisiana |page=1}}</ref> At noon on May 21, the center of Tess passed 160 km (100 mi) west of [[Marcus Island]],<ref name="CD_Annual" />{{rp|74}} bringing [[squall]]s accompanied by heavy rain and winds of 90 km/h (55 mph).<ref name="MissesMarcusIsland">{{cite news |title=Typhoon Misses Marcus Island |url=https://www.newspapers.com/clip/53323741/|via=Newspapers.com |accessdate=June 12, 2020 |work=Daily Press |agency=Associated Press |issue=134 |volume=59 |date=May 22, 1964 |location=Newport News, Virginia |page=46}}</ref><ref name="HitsMarcusIsle">{{cite news |title=Typhoon Hits Marcus Isle; Yank Missing |url=https://www.newspapers.com/clip/53324434/|via=Newspapers.com |accessdate=June 12, 2020 |work=Chicago Tribune |agency=Associated Pres |issue=144|volume=117 |date=May 23, 2020 |location=Chicago, Illinois |page=2-9}}</ref> Gusts reached 117 km/h (72 mph) and rainfall accumulations reached 94 mm (3.7 in) on the island, though there was "little damage."<ref name="May1964" /> Gradual weakening followed,<ref name="CD_Annual" />{{rp|74}} with winds diminishing below typhoon intensity on May 22. The system then began to curve east as it transitioned into an [[extratropical cyclone]] by May 24, and was last noted three days later.<ref name="IBTrACS_Tess" /> |

|||

|Basin=WPac |

|||

|Image=02W 1964 track.png |

|||

|Formed=May 16 |

|||

|Dissipated=May 17 |

|||

|Type1=nwpdepression |

|||

|Type2=depression |

|||

|1-min winds=30 |

|||

|Pressure=1002 |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

Tropical Depression 02W was a short lived depression forming just south of [[Guam]] on May 16 and moved to the northeast dissipating within 18 hours. Only four advisories were released on Tropical Depression 02W. |

|||

{{clear}} |

|||

===Tropical Depression Biring=== |

|||

{{Infobox Hurricane Small |

|||

|Basin=WPac |

|||

|Image= |

|||

|Formed=May 25 |

|||

|Dissipated=May 26 |

|||

|1-min winds=30 |

|||

|Pressure= |

|||

|WarningCenter=PAGASA |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

{{clear}} |

{{clear}} |

||

| ⚫ | |||

{| class="wikitable floatleft" |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

|+ Peak intensity estimates<ref name="IBTrACS_Viola" /> |

|||

! Agency |

|||

! Wind<br />(kt){{efn|name=MSW}} |

|||

! Pressure<br />(hPa) |

|||

|- |

|||

! CMA |

|||

| 68 || 980 |

|||

|- |

|||

! HKO |

|||

| 65 || 980 |

|||

|- |

|||

! JMA |

|||

| {{N/a}} || 980 |

|||

|- |

|||

! JTWC |

|||

| 70 || {{N/a}} |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

{{Infobox Hurricane Small |

{{Infobox Hurricane Small |

||

|Basin=WPac |

|Basin=WPac |

||

| Line 208: | Line 221: | ||

|Track=Viola 1964 track.png |

|Track=Viola 1964 track.png |

||

|Formed=May 21 |

|Formed=May 21 |

||

|Dissipated=May |

|Dissipated=May 30{{efn|name=IBTrACS}} |

||

|Type1= |

|Type1= |

||

|Type2=cat1 |

|Type2=cat1 |

||

|1-min winds=70 |

|1-min winds=70 |

||

|Pressure=980 |

|Pressure=980 |

||

}} |

}} |

||

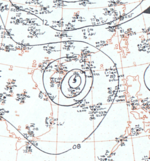

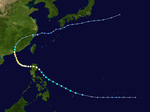

Tropical Depression 3W formed on May 25 near [[Manila]]. The depression became Tropical Storm '''Viola''' the same day, and then Typhoon Viola on the 27th. Viola peaked at <span style="white-space:nowrap">80 mph (129 km/h)</span> winds with a pressure of 980 mbar. The typhoon made landfall in Hong Kong on May 28, dissipating soon after.<ref>{{Cite web |url=http://www.usno.navy.mil/NOOC/nmfc-ph/RSS/jtwc/atcr/1964atcr/pdf/wnp/03.pdf |title=Viola Report |access-date=2009-12-24 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110606234104/http://www.usno.navy.mil/NOOC/nmfc-ph/RSS/jtwc/atcr/1964atcr/pdf/wnp/03.pdf |archive-date=2011-06-06 |url-status=dead }}</ref> |

|||

According to data from the [[Japan Meteorological Agency]] (JMA), the progenitor to Typhoon Viola emerged in the [[South China Sea]] just east of [[Vietnam]] on May 21.<ref name="IBTrACS_Viola">{{cite web |title=1964 Typhoon VIOLA (1964143N13112) |website=IBTrACS - International Best Track Archive for Climate Stewardship|url=http://www.atms.unca.edu/ibtracs/ibtracs_v04r00/index.php?name=v04r00-1964143N13112 |publisher=University of North Carolina–Asheville |accessdate=June 12, 2020 |location=Asheville, North Carolina |date=2018}}</ref> This system initially moved towards the north before curving sharply east. Three days later, the system organized into a tropical depression after the JTWC identified a surface wind circulation.<ref name="ATR" />{{rp|81}} Viola reached tropical storm strength on May 25 and then curved northwest, strengthening further into a typhoon on May 27 and peaking in strength with winds of 130 km/h (80 mph).<ref name="IBTrACS_Viola" /> These winds diminished to 110 km/h (70 mph)—just under typhoon intensity—as Viola made [[landfall (meteorology)|landfall]] approximately 160 km (100 mi) west of [[Hong Kong]] at 03:00 [[Coordinated Universal Time|UTC]] on May 28.<ref name="IBTrACS_Viola" /><ref name="CD_Annual" />{{rp|74}} The storm weakened over [[mainland China]] and dissipated on May 30.<ref name="IBTrACS_Viola" /> |

|||

Striking near Hong Kong as a tropical storm, Viola brought heavy rains and strong winds to the region, ending a two-year [[drought]]. Business was nearly brought to a standstill as roads were blocked off and transportation suspended.<ref name="SpokesmanReview1"/> Several fishing vessels ran aground and 28 people were injured.<ref>{{cite news|work=Associated Press|publisher=The Evening Independent|date=May 28, 1964|accessdate=August 7, 2011|title=Typhoon Ends Long Drought In Hong Kong|url=https://news.google.com/newspapers?id=qaAvAAAAIBAJ&sjid=_FYDAAAAIBAJ&dq=storm%20viola&pg=1310%2C4607194|page=2A}}</ref> Additionally, thousands of people living in "junk" houses were left homeless.<ref name="SpokesmanReview1">{{cite news|work=Reuters|publisher=The Spokesman-Review|date=May 29, 1964|accessdate=August 7, 2011|title=Storm Rips Hong Kong|url=https://news.google.com/newspapers?id=BWRWAAAAIBAJ&sjid=5_EDAAAAIBAJ&dq=storm%20viola&pg=1329%2C4826823|page=20}}</ref> |

|||

{{clear}} |

|||

The [[Royal Observatory Hong Kong]] issued [[Hong Kong tropical cyclone warning signals|typhoon signal No. 8]] ahead of Viola's approach, signifying gale-force conditions. Ferry services were suspended in the territory.<ref name="Pui-yin" />{{rp|66,74}} Hong Kong recorded {{cvt|300.6|mm}} of rain in five days from the passing typhoon. The rainfall brought an end to an over two-year-long [[drought]] that had prompted a year-long water rationing in the territory.<ref name="Lam et al.">{{cite journal |last1=Lam |first1=Hilda |last2=Kok |first2=Mang Hin |last3=Shum |first3=Karen Kit Ying |title=Benefits from typhoons - the Hong Kong perspective |journal=Weather |date=January 2012 |volume=67 |issue=1 |pages=16–21 |doi=10.1002/wea.836 |url=https://rmets.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/wea.836|via=John Wiley & Sons, Inc. |accessdate=June 12, 2020 |publisher=Royal Meteorological Society}} {{free access}}</ref><ref name="Chu">{{cite book |last1=Chu |first1=C. Y. |title=The Maryknoll Sisters in Hong Kong, 1921-1969 |date=2004 |publisher=Palgrave Macmillan |location=New York, New york |isbn=978-1-4039-8161-5 |edition=1st |chapter=Wong Tai Sin, Kowloon Tsai, and Social Services in the 1960s|doi=10.1057/9781403981615_6}}</ref><ref name="DeptReportsHK">{{cite web |last1=Wright |first1=A. M. J. |title=Annual Departmental Reports 1964-65 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=TU4vU-aq1Q8C|via=Google Books |publisher=Hong Kong Public Works Department |accessdate=June 12, 2020 |location=Hong Kong, China}}</ref>{{rp|72}} More rain fell in roughly 24 hours than in 1964 prior to Viola's arrival.<ref name="HongKongBaths">{{cite news |title=Viola Gave Hong Kong More Baths |url=https://www.newspapers.com/clip/53354988/|via=Newspapers.com |accessdate=June 13, 2020 |work=The Miami Herald |issue=182 |date=May 31, 1964 |location=Miami, Florida |page=20-A}}</ref> The storm uprooted trees, triggered landslides, and put over 6,000 telephones out of commission.<ref name="TyphoonDamageInHongKong">{{cite news |title=Typhoon Damage in Hong Kong |url=https://www.newspapers.com/clip/53354037/|via=Newspapers.com |accessdate=June 13, 2020 |work=St. Joseph News-Press |agency=Associated Press |issue=129 |volume=92 |date=May 28, 1964 |location=St. Joseph, Missouri |page=12B}}</ref> Vegetable crops were badly damaged.<ref name="TyphoonDamages">{{cite news |title=Typhoon Damages |url=https://www.newspapers.com/clip/53354509/|via=Newspapers.com |accessdate=June 13, 2020 |work=Great Falls Tribune |agency=United Press International |issue=17 |volume=79 |date=May 30, 1964 |location=Great Falls, Montana |page=1}}</ref> Viola generated a 0.94-meter-high (3.08 ft) [[storm surge]] at [[Quarry Bay]] and grounded four ships, including three [[freighter]]s at Hong Kong.<ref name="Lee and Wong">{{cite web |last1=Lee |first1=T. C. |last2=Wong |first2=C. F. |title=Historical Storm Surges and Storm Surge Forecasting in Hong Kong |url=https://extranet.wmo.int/pages/prog/amp/mmop/documents/JCOMM-TR/J-TR-44/SSS/papers/6_RAN_Lee_TszCheung.pdf |publisher=Hong Kong Observatory |via=World Meteorological Organization |accessdate=June 12, 2020 |location=Hong Kong, China |page=6 |format=PDF |date=October 2007}}</ref><ref name="Leaves41Injured">{{cite news |title=Typhoon Leaves 41 Injured in Hong Kong |url=https://www.newspapers.com/clip/53354648/|via=Newspapers.com |accessdate=June 13, 2020 |work=Chicago Tribune |agency=United Press International |issue=151 |date=May 30, 1964 |location=Chicago, Illinois |page=8}}</ref><ref name="CD_Annual" />{{rp|74}} Forty-one people were hospitalized by the storm and over a thousand were left homeless.<ref name="ViolaHitsHongKong">{{cite news |title=Typhoon Viola Hits Hong Kong |url=https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/104295550 |via=Trove |accessdate=June 12, 2020 |work=The Canberra Times |agency=Australian Associated Press |issue=10860 |volume=38 |date=May 29, 1964 |location=Canberra, Australia |page=11}}</ref><ref name="TyphoonDamages" /> Further inland, the storm relieved drought conditions in the Chinese province of [[Guangdong]].<ref name="Leaves41Injured" /> |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

===Typhoon Winnie (Dading)=== |

===Typhoon Winnie (Dading)=== |

||

{{Infobox Hurricane Small |

{{Infobox Hurricane Small |

||

Revision as of 22:52, 19 November 2020

This article is actively undergoing a major edit for a little while. To help avoid edit conflicts, please do not edit this page while this message is displayed. This page was last edited at 22:52, 19 November 2020 (UTC) (3 years ago) – this estimate is cached, . Please remove this template if this page hasn't been edited for a significant time. If you are the editor who added this template, please be sure to remove it or replace it with {{Under construction}} between editing sessions. |

| 1964 Pacific typhoon season | |

|---|---|

Season summary map | |

| Seasonal boundaries | |

| First system formed | May 12, 1964 |

| Last system dissipated | December 31, 1964 |

| Strongest storm | |

| Name | Sally and Opal |

| • Maximum winds | 315 km/h (195 mph) (1-minute sustained) |

| • Lowest pressure | 895 hPa (mbar) |

| Seasonal statistics | |

| Total depressions | 57 (world record high) |

| Total storms | 39 (world record high) |

| Typhoons | 26 (world record high) |

| Super typhoons | 7 (unofficial) |

| Total fatalities | ≥8,743 |

| Total damage | Unknown |

| Related articles | |

The 1964 Pacific typhoon season was the most active tropical cyclone season recorded globally, with a total of 39 tropical storms forming. It had no official bounds; it ran year-round in 1964, but most tropical cyclones tend to form in the northwestern Pacific Ocean between June and December. These dates conventionally delimit the period of each year when most tropical cyclones form in the northwestern Pacific Ocean.

Tropical Storms formed in the entire west pacific basin were assigned a name by the Joint Typhoon Warning Center. Tropical depressions in this basin have the "W" suffix added to their number. Tropical depressions that enter or form in the Philippine area of responsibility are assigned a name by the Philippine Atmospheric, Geophysical and Astronomical Services Administration or PAGASA. This can often result in the same storm having two names.

The 1964 Pacific typhoon season was the most active season in recorded history with 39 storms. Notable storms include Typhoon Joan, which killed 7,000 people in Vietnam; Typhoon Louise, which killed 400 people in the Philippines, Typhoons Sally and Opal, which had some of the highest winds of any cyclone ever recorded at 195 mph, Typhoons Flossie and Betty, which both struck the city of Shanghai, China, and Typhoon Ruby, which hit Hong Kong as a powerful 140 mph Category 4 storm, killing over 700 and becoming the second worst typhoon to affect Hong Kong.

Season summary

Timeline of tropical activity in 1964 Pacific typhoon season

The 1964 typhoon season was the most active Pacific typhoon season on record.[1][2] All months between and including May and November were featured an above-average number of typhoons relative to the 1959–1976 period.[3] The China Meteorological Administration (CMA), Hong Kong Observatory (HKO), Japan Meteorological Agency (JMA), and Joint Typhoon Warning Center (JTWC) each maintain tropical cyclone databases that include their respective intensity and path analyses for 1964, resulting in disparate storm counts and intensities.[4] Total tropical cyclone counts for the 1964 season include 40 from the CMA, 34 from the JMA, and 52 from the JTWC (including 7 considered "suspect cyclones").[4][5][6]: 47

A recommendation was made at the 20th session of the United Nations Economic Commission for Asia and the Far East (now known as the UN Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific [ESCAP]) in March 1964 for the United Nations Secretariat and World Meteorological Organization to investigate the feasibility of a multinational program for monitoring typhoons.[7] This led to the formation of the ESCAP/WMO Typhoon Committee, which held its inaugural session in 1968.[8] Prior to the inception of the Typhoon Committee, the United States Indo-Pacific Command had designated the U.S. Fleet Weather Central in Guam as the JTWC in May 1959. The JTWC was tasked with warning U.S. government agencies on tropical cyclones in the northwestern Pacific, in addition to researching and orchestrating aircraft reconnaissance into such storms.[6]: i Boeing B-47 Stratojets were deployed from the 54th Weather Reconnaissance Squadron to carry out airborne reconnaissance.[6]: 11 The JTWC issued 730 warnings on 26 typhoons, 14 tropical storms, and 5 tropical depressions. The number of typhoons was a new record, topping the 24 set in 1962.[6]: 47 Ten of these occurred in the South China Sea, compared to the annual average of 3.2 in the five years preceding 1964.[6] The anomalous strength of tropical waves observed during the latter-half of the year may have contributed to season's high activity.[9] Ten of the year's tropical cyclones—Grace, Helen, Nancy, Pamela, Ruby, Fran, Georgia, Iris, Kate, Louise, and Opal—were first detected using meteorological satellites.[10]

The active typhoon season was also impactful.[11] More storms passed near Hong Kong in 1964 than in any prior year. The Royal Observatory Hong Kong issued tropical cyclone warning signals 42 times for ten different storms; these warnings were in effect for 570 hours. Two of these storms, Ruby and Dot, prompted the highest warning signal, signal no. 10.[12] No year prior to 1964 featured more than two typhoons affecting Hong Kong on record.[13] Ten typhoons impacted the Philippines, including Winnie (known as Dading in the Philippines)[14], Luzon's severest typhoon since 1882.[11] The effects of typhoons in 1964 led to a 3.1 percent decrease in rice output from the Philippines.[15] Six typhoons and two tropical storms struck Vietnam, including three tropical cyclones in a twelve-day period in November. The combined effects of Iris and Joan killed as many as 7,000 people and led to the worst floods in six decades.[11]

In May 1964, the western Pacific was characterized by anomalously high geopotential heights towards the northern part of the basin and low geopotential heights in the tropical regions. This configuration was favorable for tropical cyclogenesis and led to the development of typhoons Tess and Viola, the first storms of the 1964 typhoon season.[6][16] Shower activity in the tropics west of Hawaii was above average between May 10–20.[17] The first half of June marked a reversal of this pattern as a large area of low pressure became established over the mid-Pacific.[18] The average sea-level pressure for the month was below normal for most of the northern Pacific.[17] Typhoons Winnie and Alice formed in the second half of the month when the initial height patterns returned.[18] July 1964 featured more tropical cyclones than any other July on record, though this was superseded by the 1971 Pacific typhoon season.[19] A strong high pressure area south of Japan caused most storms during July to take slow and westward paths.[20]

August was another above-average month for tropical activity in the basin. Pressures across most of the western Pacific were lower than average, particularly around Okinawa where tropical cyclone activity was high during the month.[21] Between August 10–19, a progression of cyclones in the upper troposphere triggered wind perturbations closer to the ocean surface, leading to the genesis of Tropical Storm June, Typhoon Kathy, Tropical Storm Lorna, and Tropical Storm Nancy.[22] Typhoons Kathy and Marie were involved in a Fujiwhara interaction that led both storms to rotate counterclockwise around each other, ending with Marie's absorption into Kathy's circulation.[23][24] A paper published in the Quarterly Journal of the Royal Meteorological Society described the resulting paths of the two storms as an "archetypal example" of the Fujiwhara interaction.[25] In September, tropical cyclone activity was high across the Northern Hemisphere in both the Atlantic and Pacific. Subtropical ridging in the Pacific was extended zonally throughout the month, resulting in strong easterly winds in the subtropical latitudes and providing conducive conditions for storm development. The extensive ridging also prevented most of September's storms from taking curved paths into the westerlies; while approximately half of September typhoons curve into the westerlies on average, only one typhoon, Wilda, took such a trajectory in 1964.[26] The strong substropical ridging continued into October, leading to similar storm paths.[27]

Systems

Typhoon Tess (Asiang)

| Agency | Wind (kt)[a] |

Pressure (hPa) |

|---|---|---|

| CMA | 97 | 966 |

| HKO | 75 | 965 |

| JMA | — | 960 |

| JTWC | 85 | — |

| Category 2-equivalent typhoon (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | May 12 – May 27[b] |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 155 km/h (100 mph) (1-min); 960 hPa (mbar) |

The first tropical cyclone of 1964 developed from a segment of the polar trough. A wind circulation was first identified near Woleai by the JTWC on May 9. This initial disturbance traveled west-northwest, passing near Ulithi and Yap.[6]: 72 On May 14, it organized further into a tropical depression and took an erratic track over the next four days, including a looping course.[28][6]: 50, 74 During this process, it strengthened into a tropical storm, weakened to a tropical depression, and reattained tropical storm intensity before heading on an east-northwestward to northeastward trajectory.[28][11]: 74 On May 19, a reconnaissance flight investigating Tess observed two eyes: the first and innermost eye measured 9.7 km (6 mi) across while the second was asymmetrical, with axes roughly 23 km (14 mi) and 14 km (9 mi) across.[6]: 75 Shortly after finding this feature, Tess was estimated to have attained typhoon status.[28]

Tess tracked towards the northeast after reaching typhoon intensity. Its center passed between Alamagan and Guguan on May 20 while maximum sustained winds in the typhoon were 140 km/h (85 mph).[28] Farther southeast, in Guam, the passing storm produced 52 mm (2.03 in) of rain.[29] The next day, Tess reached its peak intensity with winds of 155 km/h (100 mph) and a minimum barometric pressure of 960 hPa (mbar; 28.35 inHg).[28] A seabee stationed on the island was presumed to have drowned after being swept away by the rough seas generated by the storm; two landing crafts were also destroyed by the rough seas.[30] At noon on May 21, the center of Tess passed 160 km (100 mi) west of Marcus Island,[11]: 74 bringing squalls accompanied by heavy rain and winds of 90 km/h (55 mph).[31][32] Gusts reached 117 km/h (72 mph) and rainfall accumulations reached 94 mm (3.7 in) on the island, though there was "little damage."[16] Gradual weakening followed,[11]: 74 with winds diminishing below typhoon intensity on May 22. The system then began to curve east as it transitioned into an extratropical cyclone by May 24, and was last noted three days later.[28]

Typhoon Viola (Konsing)

| Agency | Wind (kt)[a] |

Pressure (hPa) |

|---|---|---|

| CMA | 68 | 980 |

| HKO | 65 | 980 |

| JMA | — | 980 |

| JTWC | 70 | — |

| Category 1-equivalent typhoon (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | May 21 – May 30[b] |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 130 km/h (80 mph) (1-min); 980 hPa (mbar) |

According to data from the Japan Meteorological Agency (JMA), the progenitor to Typhoon Viola emerged in the South China Sea just east of Vietnam on May 21.[33] This system initially moved towards the north before curving sharply east. Three days later, the system organized into a tropical depression after the JTWC identified a surface wind circulation.[6]: 81 Viola reached tropical storm strength on May 25 and then curved northwest, strengthening further into a typhoon on May 27 and peaking in strength with winds of 130 km/h (80 mph).[33] These winds diminished to 110 km/h (70 mph)—just under typhoon intensity—as Viola made landfall approximately 160 km (100 mi) west of Hong Kong at 03:00 UTC on May 28.[33][11]: 74 The storm weakened over mainland China and dissipated on May 30.[33]

The Royal Observatory Hong Kong issued typhoon signal No. 8 ahead of Viola's approach, signifying gale-force conditions. Ferry services were suspended in the territory.[12]: 66, 74 Hong Kong recorded 300.6 mm (11.83 in) of rain in five days from the passing typhoon. The rainfall brought an end to an over two-year-long drought that had prompted a year-long water rationing in the territory.[34][35][36]: 72 More rain fell in roughly 24 hours than in 1964 prior to Viola's arrival.[37] The storm uprooted trees, triggered landslides, and put over 6,000 telephones out of commission.[38] Vegetable crops were badly damaged.[39] Viola generated a 0.94-meter-high (3.08 ft) storm surge at Quarry Bay and grounded four ships, including three freighters at Hong Kong.[40][41][11]: 74 Forty-one people were hospitalized by the storm and over a thousand were left homeless.[42][39] Further inland, the storm relieved drought conditions in the Chinese province of Guangdong.[41]

Typhoon Winnie (Dading)

| Typhoon (JMA) | |

| Category 3-equivalent typhoon (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | June 24 – July 4 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 185 km/h (115 mph) (1-min); 968 hPa (mbar) |

Tropical Depression 4W formed on June 26, east of Manila. The depression quickly strengthened to a storm and was given the name Winnie the next day. The storm yet again strengthened reaching typhoon status by the 28th. On June 29, Winnie made landfall in Manila without losing much strength. While moving west, Winnie reached its peak intensity of 115 mph (185 km/h) winds and 970 mbar on July 1. Winnie then made landfall in China and dissipated over land on July 3.[43]

A total of 100 people were killed[44] and over 500,000 were left homeless throughout the Philippines due to the typhoon.[45][46][47] Thousands of poorly constructed homes were destroyed and Manila, the largest city in the Philippines with home to over 2.5 million people, was paralyzed by the storm.[48] The entire city suffered a blackout from Winnie, and officials reported that it would take days to begin restoring power. High winds downed large billboards and tore roofs off many structures as well as uprooting trees. Thousands of residents were left homeless by the storm. Torrential rains triggered widespread flooding throughout the affected region, isolating several communities. Sea and airports were closed for several days due to the system.[49] Damage from the storm were estimated to be in the tens of millions, making Winnie the worst storm to strike the country in roughly 30 years.[50]

Tropical Storm Alice

| Tropical storm (JMA) | |

| Category 1-equivalent typhoon (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | June 27 – June 29 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 120 km/h (75 mph) (1-min); 1000 hPa (mbar) |

Tropical Depression 5W formed on June 26 in the open Pacific moving west. The depression quickly strengthened and was given the name Alice. The storm makes landfall in Guam on the 27th and also reached its peak intensity of 75 mph (121 km/h) with a pressure of 990 mbar. Alice was absorbed by Typhoon Winnie on June 28 near Yap.[51]

Tropical Depression 06W

| Tropical depression (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | June 29 – July 2 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 45 km/h (30 mph) (1-min); |

Tropical Depression 6W formed on June 29 from the remnants of Typhoon Alice in Bicol Region, Philippines. The depression never strengthened into a tropical storm and dissipated four days later on July 2 in Guandong, China.

Typhoon Betty (Edeng)

| Typhoon (JMA) | |

| Category 3-equivalent typhoon (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | July 2 – July 7 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 205 km/h (125 mph) (1-min); 960 hPa (mbar) |

Tropical Depression 7W formed east of Taiwan on July 2. The depression moved west and strengthened into a storm the same day. Betty moved west, peaking at 125 mph (201 km/h) winds the next day. After passing Shanghai, China on July 6, rapid weakening occurred and Betty dissipated.[52]

Tropical Depression Gloring

| Tropical depression (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | July 5 – July 7 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 55 km/h (35 mph) (1-min); |

Super Typhoon Cora (Huaning)

| Typhoon (JMA) | |

| Category 5-equivalent super typhoon (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | July 5 – July 11 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 260 km/h (160 mph) (1-min); 970 hPa (mbar) |

Tropical Depression 8W formed west of Truk on July 4. The depression moved west and strengthened into a tropical storm on July 6. Rapid strengthening occurred and Cora reached super typhoon status by July 8. Cora peaked at 160 mph (260 km/h) winds and a minimum pressure of 970 mbar (which is unusual for a tropical cyclone; 970 mbar should be for Category 2 storms) that day. As fast as the strengthening happened, Cora then rapidly weakened, making landfall in The Philippines as a tropical storm on July 10. Cora dissipated the same day over water.[53]

Severe Tropical Storm Doris (Isang)

| Severe tropical storm (JMA) | |

| Category 1-equivalent typhoon (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | July 11 – July 17 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 150 km/h (90 mph) (1-min); 995 hPa (mbar) |

Tropical Depression 9W formed on July 9 southeast of Truk. The depression moved to the northeast, reaching tropical storm status and receiving the name Doris on July 11. Strengthening was slow, and because of that, Doris did not reach typhoon status until July 13. Doris, on the 13th reached its peak intensity of 995 mbar with 90 mph (145 km/h) winds. Rapid weakening occurred, thus Doris dissipated on July 15 near Okinawa.[54]

Severe Tropical Storm Elsie (Lusing)

| Severe tropical storm (JMA) | |

| Category 3-equivalent typhoon (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | July 14 – July 19 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 185 km/h (115 mph) (1-min); 1000 hPa (mbar) |

Tropical Depression 10W formed on July 13 west of Saipan. Slow strengthening occurred, thus 10W did not reach tropical storm status until the 15th and was given the name Elsie. After reaching tropical storm status, moderate strengthening occurred, as Elsie reached typhoon intensity on late on the 16th. Rapid strengthening finally occurred, reaching a peak of 100 knots (115 mph) on July 17 and soon made landfall in The Philippines. Elsie weakened and dissipated over water on the 18th.[55]

Tropical Depression 11W (Maring)

| Tropical depression (JMA) | |

| Tropical depression (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | July 21 – July 23 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 55 km/h (35 mph) (1-min); 1006 hPa (mbar) |

Tropical Depression 11W formed out in the open Pacific Ocean on July 21 and moved west. The depression dissipated on July 23 east of the Philippines, without making landfall.

Typhoon Flossie (Nitang)

| Typhoon (JMA) | |

| Category 1-equivalent typhoon (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | July 24 – July 29 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 150 km/h (90 mph) (1-min); 980 hPa (mbar) |

The tropical wave that spawned Typhoon Flossie formed as Tropical Depression 12W on July 26. Rapid strengthening occurred and the depression was given the name Flossie that same day. Flossie strengthened rapidly to a 90 mph (145 km/h) typhoon and then made landfall near Shanghai, China on the 27th. Flossie quickly weakened, making its second landfall in Korea and dissipating over land on the 29th.[56]

In Okinawa, rough seas from the storm led to the collision of two U.S. Navy vessels and another to run aground. Damage sustained by the ships was reported to be minor.[57] In South Korea, two fishermen drowned and a third was listed as missing after the typhoon brushed northern portions of the country. Offshore, 15 fishing boats were destroyed.[58]

Tropical Storm Grace (Osang)

| Tropical storm (JMA) | |

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | July 25 – August 4 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 95 km/h (60 mph) (1-min); 998 hPa (mbar) |

Tropical Depression 13W formed on July 26 southwest of Iwo Jima. Strengthening occurred and 13W was given the name Grace. Grace strengthened into a 60 mph (97 km/h) tropical storm. Grace made a curve on the 29th and dissipated the next day. Strengthening re-occurred and Grace reached tropical storm status on August 3. Grace finally dissipated the next day. (see below)

Super Typhoon Helen

| Typhoon (JMA) | |

| Category 4-equivalent typhoon (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | July 27 – August 4 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 240 km/h (150 mph) (1-min); 930 hPa (mbar) |

Tropical Depression 14W formed late on July 27 west of Wake Island. The depression strengthened quickly, reaching tropical storm status that same day and receiving the name Helen. Rapid strengthening occurred which caused Helen to become a typhoon on the 29th. By July 30, Helen was a Category 4 super typhoon just south of Iwo Jima. That same day, Helen just passed by Iwo Jima. Rapid weakening occurred and Helen made landfall in China as a 50 mph (80 km/h) tropical storm on August 3. Helen dissipated over land the same day.[59]

Tropical Depression Paring

| Tropical depression (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | July 31 – August 1 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 55 km/h (35 mph) (1-min); |

Tropical Depression Reming

| Tropical depression (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | August 1 – August 2 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 55 km/h (35 mph) (1-min); |

Super Typhoon Ida (Seniang)

| Typhoon (JMA) | |

| Category 4-equivalent typhoon (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | August 2 – August 12 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 250 km/h (155 mph) (1-min); 925 hPa (mbar) |

The interaction between the polar trough and an easterly wave developed into Tropical Depression 15W on August 2. It moved to the west-northwest, quickly strengthening into a tropical storm later on the 2nd and into a typhoon on the 4th. Ida rapidly intensified to a 155 mph (249 km/h) super typhoon on the 6th, and struck northeastern Luzon at that intensity that night. After weakening over the island, Ida turned to the northwest and hit southeastern China near Hong Kong on August 8 as a 100 mph (160 km/h) typhoon. The storm killed 75 people, and caused moderate to heavy damage on its path.[60]

Eleven deaths in Luzon were attributed to Ida, in addition to flooding and crop damage throughout the island.[61] U.S. Navy ships stationed at U.S. Naval Base Subic Bay were evacuated into the South China Sea prior to the storm's arrival.[62] People in low-lying fishing villages left for higher ground.[63] A 3,541-short-ton (3,212-metric-ton) freighter sustained damage to its bilge upon being grounded near Aparri.[61] Ida disrupted communications across Luzon. Streets in Manila were flooded to waist-height.[63] In Hong Kong, the Royal Observatory Hong Kong advised ships to seek shelter in port.[64]

Tropical Depression 16W

| Tropical depression (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | August 3 – August 4 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 30 km/h (15 mph) (1-min); |

The apparent 16th system of the 1964 typhoon season was recorded to be the reformed Tropical Storm Grace on August 3 and 4th.[65]

Tropical Storm June (Toyang)

| Tropical storm (JMA) | |

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | August 9 – August 17 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 75 km/h (45 mph) (1-min); 998 hPa (mbar) |

Tropical Depression 17W formed on August 10 in the open Pacific Ocean. Slow intensifying occurred, and 17W was given the name June. June quickly peaked at 45 mph (72 km/h) and dissipated on the 13th north of Luzon.

Typhoon Kathy (Welpring)

| Typhoon (JMA) | |

| Category 4-equivalent typhoon (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | August 10 – August 25 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 215 km/h (130 mph) (1-min); 948 hPa (mbar) |

The 19th tropical depression of the season formed on August 10 northwest of Wake Island. The depression soon rapidly strengthen into a tropical storm and was named Kathy by the next day. Kathy continued to gain strength and was a typhoon later on the 11th. From August 15 to August 18, Kathy had a Fujiwhara interaction with Typhoon Marie, soon absorbing Marie on the 18th. More strengthening occurred and Kathy was a Category 4 typhoon by the 18th, peaking at 135 mph (217 km/h) winds. After then, Kathy made a secondary loop before forming a complete loop. After Kathy looped twice, weakening occurred and Kathy made landfall as a tropical storm in Japan on August 25, dissipating soon after.

Tropical Storm Lorna

| Tropical storm (JMA) | |

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | August 11 – August 14 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 65 km/h (40 mph) (1-min); 1002 hPa (mbar) |

Tropical Depression 18W formed northwest of Saipan on August 12. Strengthening occurred slowly, reaching tropical storm status, receiving the name Lorna and dissipating the next day at a 40 mph (64 km/h) tropical storm peak.

Typhoon Marie (Undang)

| Typhoon (JMA) | |

| Category 1-equivalent typhoon (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | August 12 – August 20 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 130 km/h (80 mph) (1-min); 980 hPa (mbar) |

Tropical Depression 20W formed far west of Hong Kong on August 14. Strengthening was slow and 20W was given the name Marie the next day. During the storm's lifetime, Marie had a Fujiwhara interaction with the stronger Typhoon Kathy, causing Marie to weaken after peaking at a 80 mph (129 km/h) typhoon and making landfall in Iwo Jima on the 17th. Marie made landfall in Japan on the 18th and was absorbed by Typhoon Kathy the same day.

Tropical Depression Nancy

| Tropical depression (JMA) | |

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | August 17 – August 19 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 65 km/h (40 mph) (1-min); 998 hPa (mbar) |

Tropical Depression 21W formed far northeast of Wake Island on August 17. The depression strengthened and was given the name Nancy. Nancy peaked at a 40 mph (64 km/h) tropical storm, dissipating over water on August 19.

Tropical Depression Olga

| Tropical depression (JMA) | |

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | August 22 – August 25 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 85 km/h (50 mph) (1-min); 996 hPa (mbar) |

Tropical Storm Olga was spawned by the 22nd tropical depression of the season forming on August 23 in the South China Sea. Olga dissipated on August 25, not strengthening farther than a 50 mph (80 km/h) tropical storm or ever making landfall.

Tropical Depression 23W

| Tropical depression (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | August 25 – August 25 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 35 km/h (25 mph) (1-min); |

Tropical Depression 23W formed on August 25, never reaching tropical storm status, and dissipated the same day as it formed. The location of this depression is unknown.

Tropical Depression Pamela

| Tropical depression (JMA) | |

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | August 25 – August 26 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 95 km/h (60 mph) (1-min); 1004 hPa (mbar) |

Tropical Depression 24W formed on August 25 as a 25 mph (40 km/h) depression southeast of Wake Island. The depression quickly strengthened, peaking at a 60 mph (97 km/h) storm named Pamela the same day. Pamela weakened rapidly and was gone by 1200 UTC August 26.

Typhoon Ruby (Yoning)

| Typhoon (JMA) | |

| Category 4-equivalent typhoon (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | September 1 – September 6 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 220 km/h (140 mph) (1-min); 970 hPa (mbar) |

Typhoon Ruby, which formed on September 1 to the northeast of Luzon, rapidly intensified on September 5 to a peak of 140 mph (230 km/h) winds. It hit near Hong Kong, causing sustained hurricane winds there just hours later, and dissipated on September 6 over China. Ruby caused over 730 fatalities and catastrophic damage.

Tropical Depression 26W

| Tropical depression (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | September 2 – September 3 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 55 km/h (35 mph) (1-min); 1006 hPa (mbar) |

Tropical Depression 26W formed northwest of Saipan on September 2. The depression moved north and dissipated on September 3, without making landfall.

Super Typhoon Sally (Aring)

| Typhoon (JMA) | |

| Category 5-equivalent super typhoon (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | September 3 – September 11 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 315 km/h (195 mph) (1-min); 895 hPa (mbar) |

Tropical Depression 27W formed on September 3 near Ponape as a 30 mph (48 km/h) depression. 27W quickly strengthened and was given the name Sally the same day. Rapid strengthening occurred as Sally moved west, reaching typhoon status by September 4, super typhoon status by the 6th and its peak intensity of 895 mbar with 195 mph (314 km/h) winds, becoming the strongest typhoon of the season on the 7th. Sally made landfall in Philippines on the 9th as a Category 5 typhoon. Weakening occurred and made landfall in China as a 115 mph (185 km/h) typhoon on the 10th, dissipating over land the same day.

Tropical Depression 28W

| Tropical depression (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | September 7 – September 7 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 45 km/h (30 mph) (1-min); |

Tropical Depression 28W formed on September 7, never reached tropical storm status, and dissipated the same day as forming. The location of this depression is unknown.

Typhoon Tilda (Basiang)

| Typhoon (JMA) | |

| Category 3-equivalent typhoon (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | September 12 – September 24 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 205 km/h (125 mph) (1-min); 965 hPa (mbar) |

A tropical wave formed between Saipan and Iwo Jima on September 12. The wave strengthened and was given the designation 29W on the 13th. Rapid strengthening occurred and the depression became Tropical Storm Tilda the same day. By the 15th, Tilda was a 105 mph (169 km/h) typhoon. Tilda made landfall in China and weakened slightly on the 16th of September. Tilda reached water again and re-strengthened to a 130 mph (210 km/h) typhoon. Tilda made landfall on the 23rd on the demarcation line of North Vietnam and South Vietnam, dissipating over land.

Typhoon Violet

| Typhoon (CMA) | |

| Category 1-equivalent typhoon (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | September 14 – September 15 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 140 km/h (85 mph) (1-min); 984 hPa (mbar) |

The 30th tropical depression formed on September 14 in the South China Sea. The depression quickly strengthened and was given the name Violet within six hours. Violet reached typhoon status the next day and made landfall in South Vietnam, dissipating over land.

Tropical Depression 31W

| Tropical depression (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | September 15 – September 15 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 55 km/h (35 mph) (1-min); 1002 hPa (mbar) |

Tropical Depression 31W formed on September 15, never reached tropical storm status, and dissipated the same day. The location of this depression is unknown.

Super Typhoon Wilda

| Typhoon (JMA) | |

| Category 5-equivalent super typhoon (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | September 16 – September 25 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 280 km/h (175 mph) (1-min); 895 hPa (mbar) |

Super Typhoon Wilda, having started on September 19 and reaching a peak of 175 mph (282 km/h) on the 21st, steadily weakened after its peak. It turned northward and northeastward, and made landfall on southern Japan on the 24th as a 115 mph (185 km/h) typhoon, and became extratropical the next day. Wilda left 42 dead or missing from its heavy flooding.

CMA Tropical Depression 25

| Tropical depression (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | September 20 – September 23 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 55 km/h (35 mph) (1-min); 998 hPa (mbar) |

Tropical Storm Anita

| Tropical storm (JMA) | |

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | September 23 – September 28 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 95 km/h (60 mph) (1-min); 996 hPa (mbar) |

The 33rd depression of the season formed near South Vietnam on September 24. The depression strengthened into Tropical Storm Anita the next day. Anita's strength changed rapidly on the 25th and 26th, reaching its peak intensity of 60 mph (97 km/h) on the 26th. Anita dissipated over water on September 27.

Severe Tropical Storm Billie (Kayang)

| Severe tropical storm (JMA) | |

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | September 24 – October 2 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 110 km/h (70 mph) (1-min); 994 hPa (mbar) |

The 34th depression formed from a tropical wave west of Guam on September 25. The depression moved west, slowly strengthening to a tropical storm on the 27th. The storm made landfall in The Philippines the next day and peaked at 70 mph (113 km/h) the day after. Billie dissipated over water on October 1.

Typhoon Clara (Dorang)

| Typhoon (JMA) | |

| Category 1-equivalent typhoon (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | October 1 – October 8 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 150 km/h (90 mph) (1-min); 980 hPa (mbar) |

Tropical Depression 35W formed on October 2 near The Philippines. The depression became Tropical Storm Clara the same day. Clara moved westward and gained strength slowly, reaching typhoon status on October 4 near The Philippines. Clara made landfall in Samoa on the 5th after it reached its peak at 90 mph (145 km/h). The storm continued westward and made landfall in North Vietnam, dissipating after landfall on the 8th.

Typhoon Dot (Enang)

| Typhoon (JMA) | |

| Category 2-equivalent typhoon (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | October 7 – October 15 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 165 km/h (105 mph) (1-min); 980 hPa (mbar) |

Forming on October 6, Typhoon Dot hit northern Luzon on October 9 as an 80 mph (129 km/h) storm. It continued northwestward, and reached a peak of 100 mph (160 km/h) before hitting near Hong Kong on October 13, becoming the second typhoon to cause sustained hurricane winds in Hong Kong in the same season. Up to this date 1964 was the only year in which two typhoons caused sustained hurricane winds in Hong Kong in the same year. Dot dissipated quickly, after leaving 36 dead or missing, with 85 people injured from the typhoon.

Tropical Depression Ellen

| Tropical depression (JMA) | |

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | October 8 – October 10 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 85 km/h (50 mph) (1-min); 998 hPa (mbar) |

Tropical Depression 37W formed west of Kawalein on October 8, peaking at a 50 mph (80 km/h) tropical storm and was given the name Ellen. Ellen dissipated on October 10 near Ponape.

Severe Tropical Storm Fran

| Severe tropical storm (JMA) | |

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | October 13 – October 21 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 95 km/h (60 mph) (1-min); 996 hPa (mbar) |

Tropical Depression 38W formed on October 15 near Wake Island. The depression strengthened into Tropical Storm Fran soon later. The storm peaked at 60 mph (97 km/h), the storm made a curve to the north and dissipated on October 17.

Tropical Storm Georgia (Grasing)

| Tropical storm (JMA) | |

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | October 18 – October 24 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 85 km/h (50 mph) (1-min); 994 hPa (mbar) |

Tropical Depression 39W formed west of the Philippines on October 20. During the formative stage, 39W crossed paths with the active Tropical Depression 40W. The depression stormed westward, reaching storm status on the same day and received the name Georgia after landfall in the Philippines. Georgia continued to move westward peaking at 45 knots and made landfall in North Vietnam on October 23. Georgia dissipated over land.

Tropical Depression 40W

| Tropical depression (JMA) | |

| Tropical depression (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | October 20 – October 24 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 55 km/h (35 mph) (1-min); 1004 hPa (mbar) |

Tropical Depression 40W formed northeast of Truk on October 20. The depression moved west and soon crossed paths with the soon-to-be Tropical Storm Georgia. 40W threatened both the islands of Yap and Ulithi on the 23rd. The depression dissipated on October 24.

Typhoon Hope (Hobing)

| Typhoon (JMA) | |

| Category 1-equivalent typhoon (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | October 24 – October 30 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 140 km/h (85 mph) (1-min); 975 hPa (mbar) |

Tropical Depression 41W formed near Guam late on October 23. The depression gained strength and was given the name Hope within six hours. Strengthening occurred slowly and Hope reached typhoon intensity on October 27. The storm peaked at 85 mph (137 km/h) winds on the 28th near Chichi Jima. The storm weakened over water and became extratropical on the 30th near Japan.

Tropical Depression 42W

| Tropical depression (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | October 30 – November 4 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 35 km/h (25 mph) (1-min); |

Tropical Depression 42W formed on October 30 and lasted for several days over water. 42W dissipated on November 4, never reaching tropical storm status. The location of this depression is unknown.

Tropical Storm Iris

| Tropical storm (JMA) | |

| Category 1-equivalent typhoon (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | October 31 – November 5 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 120 km/h (75 mph) (1-min); 996 hPa (mbar) |

On November 1, the JTWC began monitoring a tropical disturbance over the South China Sea, near the western Philippines. The following day, the system quickly organized as it moved in a general eastward direction. During the afternoon, the JTWC issued their first advisory on the system, immediately declaring it Tropical Storm Iris. After briefly taking a northeasterly track, Iris turned towards the southeast and reconnaissance planes recorded a developing eyewall. The following day, the a pressure of 1000 mbar (hPa) was recorded in the center of the storm; however, this reading was not taken at the storm's highest intensity.[66] On November 4, Iris intensified into a minimal typhoon, attaining winds of 120 km/h (75 mph)[67] and featured a circular 18 mi (29 km) wide eye. Several hours later, the storm made landfall in central South Vietnam at this strength. Rapid weakening took place shortly thereafter, with the storm dissipating late on November 4 over the high terrain of Vietnam.[66]

Tropical Storm Iris brought significant rainfall to parts of Vietnam, resulting in significant flooding. However, a few days after Iris moved through the country, Tropical Storm Joan worsened the situation significantly.[68]

Tropical Storm Joan

| Tropical storm (JMA) | |

| Category 1-equivalent typhoon (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | November 4 – November 11 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 130 km/h (80 mph) (1-min); 1000 hPa (mbar) |

The deadliest storm of the 1964 season, Tropical Storm Joan brought heavy flooding that killed 7,000 people in Vietnam.[68]

Similar to the formation of Tropical Storm Iris, Tropical Storm Joan originated from a tropical disturbance over the western South China Sea on November 5. Tracking eastward, the system quickly organized and was immediately declared a tropical storm on November 6. Early the next day, a reconnaissance plane recorded a pressure of 1000 mbar (hPa), the lowest in relation to Joan; however, this was measured while the system was a minimal tropical storm. Continued development took place over the following day as a well-defined wall cloud developed within the system.[69] Joan attained typhoon intensity during the afternoon of November 8 and reached its peak intensity with winds of 130 km/h (80 mph) shortly thereafter.[70] Tropical Storm Joan made landfall in nearly the same location as Typhoon Iris in central Vietnam before rapidly weakening over land. The system eventually weakened to a tropical depression on November 9 before dissipating over Laos.[69]

Due to the rapid succession of tropical storms Iris and Joan, widespread flooding and catastrophic flooding was reported across central South Vietnam. Roughly 90% of structures in three provinces were damaged by the storms and nearly one million were estimated to have been left homeless. Military operations during the Vietnam War were suspended by the typhoons.

Typhoon Kate

| Typhoon (JMA) | |

| Category 1-equivalent typhoon (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | November 10 – November 17 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 150 km/h (90 mph) (1-min); 990 hPa (mbar) |

A tropical wave was spotted off South Vietnam on November 12. The wave became Tropical Depression 45W on the 13th. The depression quickly strengthened into Tropical Storm Kate the same day. Kate made a curve to the west as a 60 mph (97 km/h) tropical storm. Kate strengthened into a typhoon on the 15th and a peak at 90 mph (145 km/h) winds the next day. Kate made landfall over South Vietnam on the 17th, dissipating over land.

Super Typhoon Louise–Marge (Ining–Liling)

| Typhoon (JMA) | |

| Category 5-equivalent super typhoon (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | November 14 – November 26 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 305 km/h (190 mph) (1-min); 915 hPa (mbar) |

The monsoon trough spawned Tropical Depression 46W on November 15 east of the Philippines. It moved westward, reaching tropical storm status later on the 15th and typhoon status on the 16th. Louise rapidly intensified, and peaked at 190 mph (310 km/h) on the 18th. The super typhoon weakened slightly to 160 mph (260 km/h) before hitting the southeast Philippines on the 19th. Louise dissipated over the archipelago on November 20, after causing 595 fatalities.

Forming from the remnants of Louise, Tropical Depression 48W formed on November 21 near The Philippines. The depression made landfall in the Philippines just after forming. The depression was finally given the name Marge on the same day. Marge quickly strengthened to a 65 mph (105 km/h) tropical storm the next day. Weakening occurred and Marge dissipated over water on November 24.

Tropical Depression 47W

| Tropical depression (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | November 19 – November 20 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 35 km/h (25 mph) (1-min); |

Tropical Depression 47W formed on November 19, never reached tropical storm status, and dissipated on November 20. The location of this depression is unknown.

Tropical Storm Nora (Moning)

| Tropical storm (JMA) | |

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | November 26 – December 2 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 100 km/h (65 mph) (1-min); 995 hPa (mbar) |

The 49th tropical depression formed near the Philippines on November 27. The depression brushed the area and strengthened into Tropical Storm Nora. Nora quickly weakened into a depression and dissipated the next day, peaking at only 65 mph (105 km/h).

Tropical Depression 50W

| Tropical depression (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | December 5 – December 5 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 35 km/h (25 mph) (1-min); |

Tropical Depression 50W formed on December 5, never reached tropical storm status, and dissipated the same day. The location of this depression is unknown. 50W was tied for the shortest living system of the season with 23W, 28W and 31W.

Super Typhoon Opal (Naning)

| Typhoon (JMA) | |

| Category 5-equivalent super typhoon (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | December 9 – December 16 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 315 km/h (195 mph) (1-min); 895 hPa (mbar) |

A tropical wave formed off the coast of Kosrae on December 8. The wave strengthened and was declared Tropical Depression 51W near Chuuk late the same day. 51W quickly strengthened into a tropical storm and was given the name Opal. Rapid strengthening occurred and Opal was a typhoon by the next day near Chuuk. Opal strengthened again into a super typhoon the next day, reaching its peak intensity of 195 mph (314 km/h) winds and a minimum pressure of 895 mbar. Opal grazed the Philippines as a Category 5 super typhoon on the 13th. Opal quickly weakened and dissipated near Hong Kong on the 16th.

Tropical Depression 52W

| Tropical depression (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | December 10 – December 12 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 55 km/h (35 mph) (1-min); 1000 hPa (mbar) |

Tropical Depression formed near the International Date Line on December 10. The depression moved to the west and soon made a curve to south. 52W dissipated on December 12 near the island of Nauru.

Tropical Depression 53W

| Tropical depression (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | December 29 – December 28 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 45 km/h (30 mph) (1-min); 1002 hPa (mbar) |

Storm names

International

During the season 39 named tropical cyclones developed in the Western Pacific and were named by the Joint Typhoon Warning Center, when it was determined that they had become tropical storms. These names were contributed to a revised list starting in late 1949, which now includes both female and male names.

| Tess | Viola | Winnie | Alice | Betty | Cora | Doris | Elsie | Flossie | Grace | Helen | Ida | June | Kathy | Lorna |

| Marie | Nancy | Olga | Pamela | Ruby | Sally | Tilda | Violet | Wilda | Anita | Billie | Clara | Dot | Ellen | Fran |

| Georgia | Hope | Iris | Joan | Kate | Louise | Marge | Nora | Opal |

After the season JTWC announced that the name Tilda would be removed from the list and the name selected to replace it was Therese which was first used in the 1967 season.

Philippines

| Asiang | Biring | Konsing | Dading | Edeng |

| Gloring | Huaning | Isang | Lusing | Maring |

| Nitang | Osang | Paring | Reming | Seniang |

| Toyang | Undang | Welpring | Yoning | |

| Auxiliary list | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aring | ||||

| Basiang | Kayang | Dorang | Enang | Grasing |

| Hobing | Ining | Liling | Moning | Naning |

| Oring | ||||

The Philippine Atmospheric, Geophysical and Astronomical Services Administration uses its own naming scheme for tropical cyclones in their area of responsibility. PAGASA assigns names to tropical depressions that form within their area of responsibility and any tropical cyclone that might move into their area of responsibility. PAGASA uses its own naming scheme that starts in the Filipino alphabet, with names of Filipino female names ending with "ng" (A, B, K, D, etc.). Should the list of names for a given year prove to be insufficient, names are taken from an auxiliary list, the first 6 of which are published each year before the season starts (in this case, all of them are used up and more auxiliary names are given). All of the storm names here are used for the first time (and only, in case of Dading). The names not retired from this list will be used again in the 1968 season.

After the season, PAGASA announced that the name Dading would be stricken out form its naming lists due to its impacts and was replaced by Didang which was first used during the 1968 season, this name was later retired by the Agency during the 1976 Pacific typhoon season and replaced with Ditang which was first used during the 1980 season.

See also

Notes

- ^ a b The Joint Typhoon Warning Center (JTWC) estimates the maximum sustained wind of a tropical cyclone has the highest windspeed averaged over one minute, the China Meteorological Administration (CMA) averages such winds over two minutes, and the Hong Kong Observatory (HKO) and Japan Meteorological Agency (JMA) averages such winds over ten minutes in their historical records.[4]

- ^ a b Storm durations and intensities are based on the International Best Track Archive for Climate Stewardship (IBTrACS), which is endorsed by the World Meteorological Organization's Tropical Cyclone Programme as "an official archiving and distribution resource for tropical cyclone best track data." However, different meteorological agencies, including the JTWC, Japan Meteorological Agency, China Meteorological Administration, and Hong Kong Observatory have disparate datasets for tropical cyclone histories that may not precisely reflect the storm attributes listed here.

References

- ^ "A Tale of Two Cyclone Seasons". Earth Observatory. NASA Goddard Space Flight Center. December 7, 2013. Retrieved June 13, 2020.

- ^ Wiltgen, Nick (October 1, 2012). "Jelawat Strikes Mainland Japan After Slamming Okinawa". The Weather Channel. TWC Product and Technology. Retrieved June 13, 2020.

- ^ An Atlas of 1976 GEOS-3 Radar Altimeter Data for Tropical Cyclone Studies (PDF) (Report). NASA Technical Memorandum. Wallops Island, Virginia: National Aeronautics and Space Administration. April 1979. p. 4.1-4. 73282. Retrieved June 26, 2020.

- ^ a b c Ying, Ming; Zhang, Wei; Yu, Hui; Lu, Xiaoqin; Feng, Jingxian; Fan, Yongxiang; Zhu, Yongti; Chen, Dequan (1 February 2014). "An Overview of the China Meteorological Administration Tropical Cyclone Database". Journal of Atmospheric and Oceanic Technology. 31 (2): 287–301. doi:10.1175/JTECH-D-12-00119.1.

- ^ "RSMC Best Track Data (Text)". RSMC Tokyo-Typhoon Center. Tokyo, Japan: Japan Meteorological Agency. Retrieved June 24, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Cassidy, Richard M., ed. (February 15, 1964). Annual Typhoon Report, 1964 (PDF) (Report). Annual Typhoon Report. Guam, Mariana Islands: Fleet Weather Central/Joint Typhoon Warning Center. Retrieved June 12, 2020.

- ^ Yu, Jixin; Liu, Jinping (February 2018). "Review of ESACP/WMO Typhoon Committee Development in Past 50 Years". Tropical Cyclone Research and Review. 7 (1). The Shanghai Typhoon Institute of China Meteorological Administration. doi:10.6057/2018TCRR01.01 – via ScienceDirect.

- ^ "The Committee Chronology – 1964-1968". ESCAP/WMO Typhoon Committee.

- ^ Chang, C-P.; Morris, V. F.; Wallace, J. M. (March 1970). "A Statistical Study of Easterly Waves in the Western Pacific: July–December 1964". Journal of the Atmospheric Sciences. 27 (2). American Meteorological Society: 195–201. doi:10.1175/1520-0469(1970)027<0195:ASSOEW>2.0.CO;2.

- ^ Significant Achievements in Satellite Meteorology 1958-1964 (Report). Significant Achievements In... Washington, D.C.: National Aeronautics and Space Administration. 1966. SP-94. Retrieved June 22, 2020 – via Google Books.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Climatological Data: National Summary (Annual 1964)" (PDF). Climatological Data. 15 (13). Asheville, North Carolina: United States Weather Bureau. 1965. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 12, 2020. Retrieved June 12, 2020 – via National Centers for Environmental Information.

{{cite journal}}:|archive-date=/|archive-url=timestamp mismatch; June 13, 2020 suggested (help) - ^ a b Pui-yin, Ho (2003). "A Review of Natural Disasters of the Past". Weathering the Storm: Hong Kong Observatory and Social Development (PDF). Hong Kong, China: Hong Kong University Press. ISBN 9622097014. Retrieved June 13, 2020.

- ^ "Hong Kong In Path of Typhoon Sally". The Arizona Republic. Phoenix, Arizona. United Press International. September 10, 1964. p. 2. Retrieved July 3, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ de Viana, Augusto V. (2014). "The Philippines' Typhoon Alley:The Historic Bagyos of the Philippines and Their Impact". Jurnal Kajian Wilayah. 5 (2). Jakarta, Indonesia: Research Center for Regional Resources. Retrieved June 13, 2020.

- ^ Hayden, Howard (1967). Higher Education and Development in South-East Asia, Volume II: Country Profiles (PDF). United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. p. 548. Retrieved June 26, 2020 – via Education Resources Information Center.

- ^ a b Green, Raymond A. (August 1964). "The Weather and Circulation of May 1964" (PDF). Monthly Weather Review. 92 (8). American Meteorological Society: 374–380. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1964)092<0374:TWACOM>2.3.CO;2. Retrieved June 14, 2020.

- ^ a b "Smooth Log, North Pacific Weather: May and June 1964". Mariners Weather Log. 8 (6). Silver Spring, Maryland: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration: 205–211. November 1964.

- ^ a b Dickson, Robert R. (September 1964). "The Weather and Circulation of June 1964" (PDF). Monthly Weather Review. 92 (9). American Meteorological Society: 428–433. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1964)092<0428:TWACOJ>2.3.CO;2. Retrieved June 14, 2020.

- ^ "Rough Log, North Pacific Weather: June and July 1971". Mariners Weather Log. 15 (5). Silver Spring, Maryland: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration: 327. September 1971.

- ^ Andrews, James F. (September 1964). "The Weather and Circulation of July 1964" (PDF). Monthly Weather Review. 92 (10). American Meteorological Society: 477–482. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1964)092<0477:TWACOJ>2.3.CO;2. Retrieved June 14, 2020.

- ^ "Smooth Log, North Pacific Weather: July and August 1964". Mariners Weather Log. 9 (1). Silver Spring, Maryland: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration: 18–20. January 1965.

- ^ Atkinson, Gary D. (April 1, 1971). "Tropical Synoptic Models". Forecasters' Guide to Tropical Meteorology. Air Weather Service. p. 7-25. Retrieved June 26, 2020 – via Google Books.

- ^ Dong, Keqin; Neumann, Charles J. (May 1983). "On the Relative Motion of Binary Tropical Cyclones". Monthly Weather Review. 111 (5). American Meteorological Society: 945–953. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1983)111<0945:OTRMOB>2.0.CO;2.

- ^ O'Connor, Neil F. (October 1964). "The Fujiwara Effect". Weatherwise. 17 (5): 232–233. doi:10.1080/00431672.1964.9941044.

- ^ Lander, Mark; Holland, Greg J. (October 1993). "On the interaction of tropical-cyclone-scale vortices. I: Observations". Quarterly Journal of the Royal Meteorological Society. 119 (514): 1347–1361. doi:10.1002/qj.49711951406.

- ^ Green, Raymond A. (December 1964). "The Weather and Circulation of September 1964" (PDF). Monthly Weather Review. 92 (12). American Meteorological Society: 601–606. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1964)092<0601:TWACOS>2.3.CO;2. Retrieved June 24, 2020.

- ^ O'Connor, James F. (January 1965). "The Weather and Circulation of October 1964" (PDF). Monthly Weather Review. 93 (1). American Meteorological Society: 59–66. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1965)093<0059:AUDM>2.3.CO;2. Retrieved June 24, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g "1964 Typhoon TESS (1964133N10134)". IBTrACS - International Best Track Archive for Climate Stewardship. Asheville, North Carolina: University of North Carolina–Asheville. 2018. Retrieved June 12, 2020.

- ^ Weir, Robert C. (October 25, 1983). Tropical Cyclones Affecting Guam (1671–1980) (PDF) (Report). San Francisco, California: Joint Typhoon Warning Center. Retrieved June 12, 2020.

- ^ "Texas Man Believed Drowned in Typhon". Shreveport Journal. Vol. 70. Shreveport, Louisiana. Associated Press. May 23, 1964. p. 1. Retrieved June 12, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Typhoon Misses Marcus Island". Daily Press. Vol. 59, no. 134. Newport News, Virginia. Associated Press. May 22, 1964. p. 46. Retrieved June 12, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Typhoon Hits Marcus Isle; Yank Missing". Chicago Tribune. Vol. 117, no. 144. Chicago, Illinois. Associated Pres. May 23, 2020. p. 2-9. Retrieved June 12, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c d e "1964 Typhoon VIOLA (1964143N13112)". IBTrACS - International Best Track Archive for Climate Stewardship. Asheville, North Carolina: University of North Carolina–Asheville. 2018. Retrieved June 12, 2020.

- ^ Lam, Hilda; Kok, Mang Hin; Shum, Karen Kit Ying (January 2012). "Benefits from typhoons - the Hong Kong perspective". Weather. 67 (1). Royal Meteorological Society: 16–21. doi:10.1002/wea.836. Retrieved June 12, 2020 – via John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

- ^ Chu, C. Y. (2004). "Wong Tai Sin, Kowloon Tsai, and Social Services in the 1960s". The Maryknoll Sisters in Hong Kong, 1921-1969 (1st ed.). New York, New york: Palgrave Macmillan. doi:10.1057/9781403981615_6. ISBN 978-1-4039-8161-5.

- ^ Wright, A. M. J. "Annual Departmental Reports 1964-65". Hong Kong, China: Hong Kong Public Works Department. Retrieved June 12, 2020 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Viola Gave Hong Kong More Baths". The Miami Herald. No. 182. Miami, Florida. May 31, 1964. p. 20-A. Retrieved June 13, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Typhoon Damage in Hong Kong". St. Joseph News-Press. Vol. 92, no. 129. St. Joseph, Missouri. Associated Press. May 28, 1964. p. 12B. Retrieved June 13, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "Typhoon Damages". Great Falls Tribune. Vol. 79, no. 17. Great Falls, Montana. United Press International. May 30, 1964. p. 1. Retrieved June 13, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Lee, T. C.; Wong, C. F. (October 2007). "Historical Storm Surges and Storm Surge Forecasting in Hong Kong" (PDF). Hong Kong, China: Hong Kong Observatory. p. 6. Retrieved June 12, 2020 – via World Meteorological Organization.

- ^ a b "Typhoon Leaves 41 Injured in Hong Kong". Chicago Tribune. No. 151. Chicago, Illinois. United Press International. May 30, 1964. p. 8. Retrieved June 13, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Typhoon Viola Hits Hong Kong". The Canberra Times. Vol. 38, no. 10860. Canberra, Australia. Australian Associated Press. May 29, 1964. p. 11. Retrieved June 12, 2020 – via Trove.

- ^ "Winnie Report" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-06-06. Retrieved 2009-12-24.

- ^ Staff Writer (2006). "Philippine Disasters". Disaster Database. Retrieved September 27, 2009.

- ^ Staff Writer (July 3, 1964). "Philippine Death Toll in Typhoon Hits 89". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved September 27, 2009.

- ^ Staff Writer (July 2, 1964). "Typhoon, Leaving 43 Dead, Heads Northwest of Luzon". The New York Times. Retrieved September 27, 2009.

- ^ Staff Writer (July 2, 1964). "Toll of dead rises to 44 from typhoon". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved September 27, 2009.

- ^ Henry Hartzenbusch (June 30, 1964). "Manila Storm Kills 10". Ellensburg Daily Record. Retrieved September 27, 2009.

- ^ United Press International (June 30, 1964). "At least 10 dead as typhoon sweeps over Manila". The Bulletin. Retrieved September 27, 2009.

- ^ United Press International (June 30, 1964). "Typhoon Winnie Kills 10 In Philippine Blow". The Deseret News. Retrieved September 27, 2009.

- ^ "Alice Report" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-06-06. Retrieved 2009-12-24.

- ^ "Betty Report" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-06-06. Retrieved 2009-12-24.

- ^ "Cora Report" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-06-06. Retrieved 2009-12-24.

- ^ "Doris Report" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-06-06. Retrieved 2009-12-24.

- ^ "Elsie Report" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-06-06. Retrieved 2009-12-24.

- ^ "Flossie Report" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-06-06. Retrieved 2009-12-24.

- ^ Associated Press (July 27, 1964). "Typhoon Piles Up Navy Ships". Sarasota Journal. p. 2. Retrieved January 31, 2010.

- ^ Staff Writer (July 30, 1964). "Seoul". Reading Eagle. p. 17. Retrieved January 31, 2010.

- ^ "Helen Report" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-06-06. Retrieved 2009-12-24.

- ^ "Ida Report" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-06-06. Retrieved 2009-12-24.

- ^ a b "National Summary" (PDF). Climatological Data. 15 (13). Asheville, North Carolina: United States Weather Bureau. 1964. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 11, 2020. Retrieved March 11, 2020 – via National Centers for Environmental Information.