Anarchism and Friedrich Nietzsche

| Part of a series on |

| Anarchism |

|---|

|

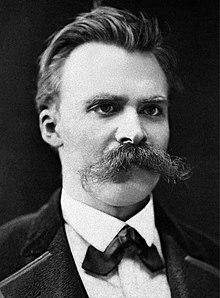

The relation between anarchism and Friedrich Nietzsche has been ambiguous. Even though Nietzsche criticized anarchists,[1] his thought proved influential for many of them.[2] As such "[t]here were many things that drew anarchists to Nietzsche: his hatred of the state; his disgust for the mindless social behavior of 'herds'; his anti-Christianity; his distrust of the effect of both the market and the State on cultural production; his desire for an 'übermensch'—that is, for a new human who was to be neither master nor slave".[2]

Overview

During the last decade of the 19th century, Nietzsche was frequently associated with anarchist movements, in spite of the fact that in his writings he seems to hold a negative view of anarchists.[1] This may be the result of a popular association during this period between his ideas and those of Max Stirner.[3][4]

Spencer Sunshine writes that "[t]here were many things that drew anarchists to Nietzsche: his hatred of the state; his disgust for the mindless social behavior of 'herds'; his anti-Christianity; his distrust of the effect of both the market and the State on cultural production; his desire for an 'overman'—that is, for a new human who was to be neither master nor slave; his praise of the ecstatic and creative self, with the artist as his prototype, who could say, 'Yes' to the self-creation of a new world on the basis of nothing; and his forwarding of the 'transvaluation of values' as source of change, as opposed to a Marxist conception of class struggle and the dialectic of a linear history".[2]

For Sunshine, "[t]he list is not limited to culturally-oriented anarchists such as Emma Goldman, who gave dozens of lectures about Nietzsche and baptized him as an honorary anarchist. Pro-Nietzschean anarchists also include prominent Spanish CNT–FAI members in the 1930s such as Salvador Seguí and anarcha-feminist Federica Montseny; anarcho-syndicalist militants like Rudolf Rocker; and even the younger Murray Bookchin, who cited Nietzsche's conception of the 'transvaluation of values' in support of the Spanish anarchist project." Also, in European individualist anarchist circles, his influence is clear in thinker/activists such as Émile Armand[5] and Renzo Novatore[6] among others. Also more recently in post-left anarchy Nietzsche is present in the thought of Albert Camus,[7] Hakim Bey, Michel Onfray, and Wolfi Landstreicher.

Max Stirner and Nietzsche

Max Stirner was a Hegelian philosopher whose "name appears with familiar regularity in historically-orientated surveys of anarchist thought as one of the earliest and best-known exponents of individualist anarchism".[8] In 1844, his The Ego and Its Own (Der Einzige und sein Eigentum which may literally be translated as The Unique Individual and His Property[9]) was published, which is considered to be "a founding text in the tradition of individualist anarchism".[8]

The ideas of 19th-century German philosophers Max Stirner and Friedrich Nietzsche have often been compared, and many authors have discussed apparent similarities in their writings, sometimes raising the question of influence.[3] In Germany, during the early years of Nietzsche's emergence as a well-known figure, the only thinker discussed in connection with his ideas more often than Stirner was Schopenhauer.[10] It is certain that Nietzsche read about Stirner's book The Ego and Its Own (Der Einzige und sein Eigentum, 1845), which was mentioned in Lange's History of Materialism (1866) and Eduard von Hartmann's Philosophy of the Unconscious (1869), both of which young Nietzsche knew very well.[11] However, there is no irrefutable indication that he actually read it, as no mention of Stirner is known to exist anywhere in Nietzsche's publications, papers or correspondence.[12]

And yet as soon as Nietzsche's work began to reach a wider audience the question of whether or not he owed a debt of influence to Stirner was raised. As early as 1891 (while Nietzsche was still alive, though incapacitated by mental illness) Eduard von Hartmann went so far as to suggest that he had plagiarized Stirner.[13] By the turn of the century the belief that Nietzsche had been influenced by Stirner was so widespread that it became something of a commonplace, at least in Germany, prompting one observer to note in 1907 "Stirner's influence in modern Germany has assumed astonishing proportions, and moves in general parallel with that of Nietzsche. The two thinkers are regarded as exponents of essentially the same philosophy."[14]

Nevertheless, from the very beginning of what was characterized as "great debate"[15] regarding Stirner's possible influence on Nietzsche—positive or negative—serious problems with the idea were noted.[16] By the middle of the 20th century, if Stirner was mentioned at all in works on Nietzsche, the idea of influence was often dismissed outright or abandoned as unanswerable.[17]

But the idea that Nietzsche was influenced in some way by Stirner continues to attract a significant minority, perhaps because it seems necessary to explain in some reasonable fashion the often-noted (though arguably superficial) similarities in their writings.[18] In any case, the most significant problems with the theory of possible Stirner influence on Nietzsche are not limited to the difficulty in establishing whether the one man knew of or read the other. They also consist in establishing precisely how and why Stirner in particular might have been a meaningful influence on a man as widely read as Nietzsche.[19]

Individualist anarchism

Individualist anarchism in the United States

The two men were frequently compared by French "literary anarchists" and anarchist interpretations of Nietzschean ideas appear to have also been influential in the United States.[20] One researcher notes: "Indeed, translations of Nietzsche's writings in the United States very likely appeared first in Liberty, the anarchist journal edited by Benjamin Tucker." He adds "Tucker preferred the strategy of exploiting his writings, but proceeding with due caution: 'Nietzsche says splendid things, – often, indeed, Anarchist things, – but he is no Anarchist. It is of the Anarchists, then, to intellectually exploit this would-be exploiter. He may be utilized profitably, but not prophetably.'"[21]

Individualist anarchism in Europe

In European individualist anarchist circles his influence might have been stronger. As such French individualist anarchist and free love propagandist Émile Armand writes in mixed Stirnerian and Nietzschetian language[22] when he describes the anarchists as those who "are pioneers attached to no party, non-conformists, standing outside herd morality and conventional 'good' and 'evil', 'a-social'. A 'species' apart, one might say. They go forward, stumbling, sometimes falling, sometimes triumphant, sometimes vanquished. But they do go forward, and by living for themselves, these 'egoists', they dig the furrow, they open the broach through which will pass those who deny archism, the unique ones who will succeed them."[5]

Italian individualist anarchist and illegalist Renzo Novatore also shows a strong influence by Nietzsche. "Written around 1921, Toward the Creative Nothing, which visibly feels the effects of Nietzsche's influence on the author, attacks Christianity, socialism, democracy, fascism one after the other, showing the material and spiritual destitution in them."[6] In this poetic essay he writes: "For you, great things are in good as in evil. But we live beyond good and evil, because all that is great belongs to beauty" and "[e]ven the spirit of Zarathustra—the truest lover of war and the most sincere friend of warriors—must have remained sufficiently disgusted and scornful since somebody heard him exclaim: 'For me, you must be those who stretch your eyes in search of the enemy of your enemy. And in some of you hatred blazes at first glance. You must look for your enemy, fight your war. And this for your ideas! And if your idea succumbs, your rectitude cries of triumph!' But alas! The heroic sermon of the liberating barbarian availed nothing."[6]

Individualist anarchism in Latin America

Argentinian anarchist historian Ángel Cappelletti reports that in Argentina: "Among the workers that came from Europe in the 2 first decades of the century, there was curiously some Stirnerian individualists influenced by the philosophy of Nietzsche, that saw syndicalism as a potential enemy of anarchist ideology. They established [...] affinity groups that in 1912 came to, according to Max Nettlau, to the number of 20. In 1911 there appeared, in Colón, the periodical El Único, that defined itself as 'Publicación individualista'".[23]

Vicente Rojas Lizcano whose pseudonym was Biófilo Panclasta, was a Colombian individualist anarchist writer and activist. In 1904 he begins using the name Biofilo Panclasta. "Biofilo" in Spanish stands for "lover of life" and "panclasta" for "enemy of all".[24] He visited more than fifty countries propagandizing for anarchism which in his case was highly influenced by the thought of Max Stirner and Friedrich Nietzsche. Among his written works there are Siete años enterrado vivo en una de las mazmorras de Gomezuela: Horripilante relato de un resucitado(1932) and Mis prisiones, mis destierros y mi vida (1929) which talk about his many adventures while living his life as an adventurer, activist and vagabond, as well as his thought and the many times he was imprisoned in different countries.

Anarcho-syndicalists and anarcho-communists

The American anarchist publication Anarchy: A Journal of Desire Armed reports that German "[a]narchist Gustav Landauer’s major work, For Socialism, is also squarely based on Nietzschean ideas."[25] This claim, however, has been revised by the political scientist Dominique Miething. He asserts that, while it is true that "Landauer’s reading of Friedrich Nietzsche presents us with the most profound appropriation of the German philosopher within the historic anarchist tradition",[26] Landauer drew a clear line to Nietzsche's notions of anti-humanism, elitism and “hardness”, for he deemed them incompatible with the positive ideals of anarchism.

Rudolf Rocker was yet another anarchist admirer of Nietzsche. A proponent of anarcho-syndicalism, "Rocker invokes Nietzsche repeatedly in his tome Nationalism and Culture, citing him especially to back up his claims that nationalism and state power have a destructive influence on culture, since 'Culture is always creative', but 'power is never creative.' Rocker even ends his book with a Nietzsche quote."[2] Rocker begins Nationalism and Culture using the theory of will to power to refute Marxism, stating that "[t]he deeper we trace the political influences in history, the more are we convinced that the 'will to power' has up to now been one of the strongest motives in the development of human social forms. The idea that all political and social events are but the result of given economic conditions and can be explained by them cannot endure careful consideration."[27] Rocker's interpretation of Nietzsche is not only directed against right-wing extremist and Nazi appropriations of the German philosopher's works, but also serves as an explicit rebuttal of Oswald Spengler's deterministic view of history in his main book The Decline of the West.[28] Rocker also translated Thus Spoke Zarathustra into Yiddish.

Sunshine says that the "Spanish anarchists also mixed their class politics with Nietzschean inspiration". Murray Bookchin, in The Spanish Anarchists, describes prominent CNT–FAI member Salvador Seguí as "an admirer of Nietzschean individualism, of the superhombre to whom 'all is permitted'". Bookchin, in his 1973 introduction to Sam Dolgoff's The Anarchist Collectives, even describes the reconstruction of society by the workers as a Nietzschean project. Bookchin says that "workers must see themselves as human beings, not as class beings; as creative personalities, not as 'proletarians,' as self-affirming individuals, not as 'masses' [...] [the] economic component must be humanized precisely by bringing an 'affinity of friendship' to the work process, by diminishing the role of onerous work in the lives of producers, indeed by a total 'transvaluation of values' (to use Nietzsche's phrase) as it applies to production and consumption as well as social and personal life".[2]

"Alan Antliff documents [in I Am Not A Man, I Am Dynamite] how the Indian art critic and anti-imperialist Ananda Coomaraswamy combined Nietzsche's individualism and sense of spiritual renewal with both Kropotkin's economics and with Asian idealist religious thought. This combination was offered as a basis for the opposition to British colonization as well as to industrialization."[2]

Anarcha-feminists

Although Nietzsche has been accused of misogyny, he has nevertheless gained the admiration of two important anarcha-feminists writer/activists. This is the case of Emma Goldman[29] and Federica Montseny.[2]

Emma Goldman

Emma Goldman was profoundly influenced by Nietzsche "so much so that all of Nietzsche's books could be mail-ordered through her magazine Mother Earth".[25] Ultimately Goldman's view of Nietzsche can be summarized when she manifests in her autobiography Living My Life, "I pointed out that Nietzsche was not a social theorist but a poet, a rebel and innovator. His aristocracy was neither of birth nor of purse; it was of the spirit. In that respect Nietzsche was an anarchist, and all true anarchists were aristocrats, I said" and "[i]n Vienna one could hear interesting lectures on modern German prose and poetry. One could read the works of the young iconoclasts in art and letters, the most daring among them being Nietzsche. The magic of his language, the beauty of his vision, carried me to undreamed-of heights. I longed to devour every line of his writings, but I was too poor to buy them."[29] Goldman even went as far as to "baptize" Nietzsche "as an honorary anarchist".[2] Emma Goldman "always combined his championing of the self-creating individual with a kind of Kropotkinist anarcho-communism".[2]

Emma Goldman, in the introductory essay called "Anarchism: What It Really Stands For" from Anarchism and Other Essays, passionately defends both Nietzsche and Max Stirner from attacks within anarchism, stating that "[t]he most disheartening tendency common among readers is to tear out one sentence from a work, as a criterion of the writer's ideas or personality. Friedrich Nietzsche, for instance, is decried as a hater of the weak because he believed in the Uebermensch. It does not occur to the shallow interpreters of that giant mind that this vision of the Uebermensch also called for a state of society which will not give birth to a race of weaklings and slaves."[30]

Another similar application of Nietzsche to feminist criticism happens in "Victims of Morality" where she states: "Morality has no terrors for her who has risen beyond good and evil. And though Morality may continue to devour its victims, it is utterly powerless in the face of the modern spirit, that shines in all its glory upon the brow of man and woman, liberated and unafraid."[31]

Later in a feminist reading of Nietzsche she writes the following: "Nietzsche's memorable maxim, 'When you go to woman, take the whip along,' is considered very brutal, yet Nietzsche expressed in one sentence the attitude of woman towards her gods [...].Religion, especially the Christian religion, has condemned woman to the life of an inferior, a slave. It has thwarted her nature and fettered her soul, yet the Christian religion has no greater supporter, none more devout, than woman. Indeed, it is safe to say that religion would have long ceased to be a factor in the lives of the people, if it were not for the support it receives from woman. The most ardent churchworkers, the most tireless missionaries the world over, are women, always sacrificing on the altar of the gods that have chained her spirit and enslaved her body."[30]

In the controversial essay "Minorities Versus Majorities", clear Nietzschetian themes emerge when she manifests that "[i]f I were to give a summary of the tendency of our times, I would say, Quantity. The multitude, the mass spirit, dominates everywhere, destroying quality."[30] "Today, as then, public opinion is the omnipresent tyrant; today, as then, the majority represents a mass of cowards, willing to accept him who mirrors its own soul and mind poverty."[30] "That the mass bleeds, that it is being robbed and exploited, I know as well as our vote-baiters. But I insist that not the handful of parasites, but the mass itself is responsible for this horrible state of affairs. It clings to its masters, loves the whip, and is the first to cry Crucify!"[30]

Federica Montseny

Federica Montseny was an editor of the Spanish individualist anarchist magazine La Revista Blanca, who later achieved infamy when as an important member of the CNT-FAI was one of the four anarchists who accepted cabinet positions in the Spanish Popular Front government.[2] "Nietzsche and Stirner—as well as the playwright Ibsen and anarchist-geographer Élisée Reclus—were her favorite writers, according to Richard Kern (in Red Years / Black Years: A Political History of Spanish Anarchism, 1911–1937). Kern says she held that the "emancipation of women would lead to a quicker realization of the social revolution" and that "the revolution against sexism would have to come from intellectual and militant 'future-women.' According to this Nietzschean concept of Federica Monteseny's, women could realize through art and literature the need to revise their own roles."[2]

Existentialist anarchism

Albert Camus is often cited as a proponent of existentialism (the philosophy that he was associated with during his own lifetime), but Camus himself refused this particular label.[32] Camus is also known as an ardent critic of Marxism and regimes based on it, and aligned himself with anarchism[7] while also being a critic of modern capitalist society and fascism.[7] Camus' The Rebel (1951) presents an anarchist view on politics,[7] influenced as much by Nietzsche as by Max Stirner. "Like Nietzsche, he maintains a special admiration for Greek and Persian heroic values and pessimism for classical virtues like courage and honor. What might be termed Romantic values also merit particular esteem within his philosophy: passion, absorption in being, sensory experience, the glory of the moment, the beauty of the world."[33] "The general secretary of the Fédération Anarchiste, Georges Fontenis, also reviewed Camus's book [The Rebel] in Le Libertaire. To the title question 'Is the revolt of Camus the same as ours?', Fontenis replied that it was."[7]

In the United Kingdom Herbert Read, who was highly influenced by Max Stirner and later came close to existentialism (see existentialist anarchism), said of Nietzsche: "It was Nietzsche who first made us conscious of the significance of the individual as a term in the evolutionary process—in that part of the evolutionary process which has still to take place."[34]

Post-left anarchy and insurrectionary anarchism

Post-left anarchist Hakim Bey while explaining his main concept of immediatism says that "[t]he penetration of everyday life by the marvelous--the creation of 'situations'—belongs to the 'material bodily principle', and to the imagination, and to the living fabric of the present [...]. The individual who realizes this immediacy can widen the circle of pleasure to some extent simply by waking from the hypnosis of the 'Spooks' (as Stirner called all abstractions); and yet more can be accomplished by 'crime'; and still more by the doubling of the Self in sexuality. From Stirner's 'Union of Self-Owning Ones' we proceed to Nietzsche's circle of 'Free Spirits' and thence to Charles Fourier's 'Passional Series', doubling and redoubling ourselves even as the Other multiplies itself in the eros of the group."[35]

A Nietzschean criticism of identity politics was provided by insurrectionary anarchist Feral Faun in "The ideology of victimization" when he affirms there's a "feminist version of the ideology of victimization—an ideology which promotes fear, individual weakness (and subsequently dependence on ideologically based support groups and paternalistic protection from the authorities)",[36] but in the end, "[l]ike all ideologies, the varieties of the ideology of victimization are forms of fake consciousness. Accepting the social role of victim—in whatever one of its many forms—is choosing to not even create one's life for oneself or to explore one's real relationships to the social structures. All of the partial liberation movements—feminism, gay liberation, racial liberation, workers' movements and so on—define individuals in terms of their social roles. Because of this, these movements not only do not include a reversal of perspectives which breaks down social roles and allows individuals to create a praxis built on their own passions and desires; they actually work against such a reversal of perspective. The 'liberation' of a social role to which the individual remains subject."[36]

Post-anarchism

Post-anarchism is a contemporary hybrid of anarchism and post-structuralism. Post-structuralism in itself is profoundly influenced by Nietzsche in its main thinkers such as Michel Foucault and Gilles Deleuze as well as the early influence of Georges Bataille on these authors. Nevertheless, within post-anarchism the British Saul Newman wrote an article called "Anarchism and the politics of ressentiment"[37] in which he notes how Nietzsche "sees anarchism as poisoned at the root by the pestiferous weed of ressentiment—the spiteful politics of the weak and pitiful, the morality of the slave"[37] and so his essay decides to "take seriously his charge against anarchism".[37] And so he proposes how "anarchism could become a new 'heroic' philosophy, which is no longer reactive but, rather, creates values"[37] and proposes a notion of community that "of active power—a community of 'masters' rather than 'slaves'. It would be a community that sought to overcome itself—continually transforming itself and revelling in the knowledge of its power to do so."[37] On the other hand, the proponent of postmodern anarchism Lewis Call wrote an essay called "Toward an Anarchy of Becoming: Nietzsche"[38] in which he argues that "despite Nietzsche's hostility towards anarchism, his writing contains all the elements of a nineteenth century anarchist politics [...] Nietzsche unleashes another kind of anarchy, an anarchy of becoming. By teaching us that we must pursue a perpetual project of self-overcoming and self-creation, constantly losing and finding ourselves in the river of becoming, Nietzsche ensures that our subjectivity will be fluid and dispersed, multiple and pluralistic rather than fixed and centered, singular and totalitarian. These twin anarchies, the critical anarchy of the subject and the affirmative anarchy of becoming, form the basis for a postmodern Nietzschetian anarchism".[39]

Recently, the French anarchist and hedonist philosopher Michel Onfray has embraced the term postanarchism to describe his approach to politics and ethics.[40] He has said that the May 68 revolts were "a Nietzschetian revolt in order to put an end to the 'One' truth, revealed, and to put in evidence the diversity of truths, in order to make disappear ascetic Christian ideas and to help arise new possibilities of existence".[41] In 2005 he published the essay De la sagesse tragique – Essai sur Nietzsche[42] which could be translated as On tragic wisdom – Essay on Nietzsche.

According to a more recent study by Dominique Miething, who has compared anarchist readings of Nietzsche's philosophy in Germany, the United Kingdom and the United States between 1890 and 1947, it is "not true that post-anarchists have introduced anything substantially new when they incorporated Nietzschean ideas into their variants of anarchism. Rather, many classical anarchists that learned from Nietzsche had already rejected typical modern ideas, for instance essentialist ontologies. It is just that post-anarchists lack the detailed knowledge of classical anarchist thought [...]".[43]

References

- ^ a b In Beyond Good and Evil (6.2:126) he refers to "anarchist dogs"

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k "Spencer Sunshine: "Nietzsche and the Anarchists" (2005)". radicalarchives.org. May 18, 2010.

- ^ a b "Nietzsche's possible reading, knowledge, and plagiarism of Max Stirner's The Ego and Its Own (1845) has been a contentious question and frequently discussed for more than a century now." Thomas H. Brobjer, "Philologica: A Possible Solution to the Stirner-Nietzsche Question", in The Journal of Nietzsche Studies - Issue 25, Spring 2003, pp. 109–114

- ^ Bernd A. Laska: Nietzsche's initial crisis. New Light on the Stirner/Nietzsche Question In: Germanic Notes and Reviews, vol. 33, n. 2, fall/Herbst 2002, pp. 109–133 (German orig.)

- ^ a b The Anarchism of Émile Armand by Émile Armand

- ^ a b c Toward the Creative Nothing by Renzo Novatore

- ^ a b c d e "Camus also supported the Groupes de Liaison Internationale which sought to give aid to opponents of fascism and Stalinism, and which refused to take the side of American capitalism.""Albert Camus and the Anarchists" by ORGANISE! Archived 2008-05-16 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Leopold, David (2006-08-04). "Max Stirner". In Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- ^ Moggach, Douglas. The New Hegelians. Cambridge University Press. p. 177

- ^ While discussion of possible influence has never ceased entirely, the period of most intense discussion occurred between c. 1892 and 1906 in the German-speaking world. During this time, the most comprehensive account of Nietzsche's reception in the German language, the 4 volume work of Richard Frank Krummel: Nietzsche und der deutsche Geist, indicates 83 entries discussing Stirner and Nietzsche. The only thinker more frequently discussed in connection with Nietzsche during this time is Schopenhauer, with about twice the number of entries. Discussion steadily declines thereafter, but is still significant. Nietzsche and Stirner show 58 entries between 1901 and 1918. From 1919 to 1945 there are 28 entries regarding Nietzsche and Stirner.

- ^ Nietzsche discovered Lange's book immediately after its appearance and praised it as "the most important philosophical work in decades" (letter to Hermann Mushacke, mid November 1866); as to Hartmann, who was also developing the ideas of Schopenhauer, Nietzsche singled out his book in his second Untimely Meditation for a caustic criticism, and concentrated on precisely the chapter dealing with Stirner, though he did not once mention Stirner's name; Hartmann wrote: ""Nietzsche does not mention at any place the name of Stirner or his writings. That he must have known my emphatic hint to Stirner's standpoint and its importance in the 'Philosophy of the Unconscious' arises from his polemic criticism of exactly that chapter which it contains. That he did not see himself prompted by this hint to get acquainted more closely with this thinker so congenial with himself is of little plausibility." Eduard von Hartmann, Ethische Studien, Leipzig: Haacke 1898, pp. 34–69

- ^ Albert Levy, Stirner and Nietzsche, Paris, 1904, p. 9

- ^ Eduard von Hartmann, Nietzsches "neue Moral", in Preussische Jahrbücher, 67. Jg., Heft 5, Mai 1891, S. 501–521; augmented version with more express reproach of plagiarism in: Ethische Studien, Leipzig, Haacke 1898, pp. 34–69

- ^ This author believes that one should be careful in comparing the two men. However, he notes: "It is this intensive nuance of individualism that appeared to point from Nietzsche to Max Stirner, the author of the remarkable work Der Einzige und sein Eigentum. Stirner's influence in modern Germany has assumed astonishing proportions, and moves in general parallel with that of Nietzsche. The two thinkers are regarded as exponents of essentially the same philosophy." Oscar Ewald, "German Philosophy in 1907", in The Philosophical Review, Vol. 17, No. 4, Jul., 1908, pp. 400–426

- ^ [in the last years of the 19th century] "The question of whether Nietzsche had read Stirner was the subject of great debate" R.A. Nicholls, "Beginnings of the Nietzsche Vogue in Germany", in Modern Philology, Vol. 56, No. 1, Aug., 1958, pp. 29–30

- ^ Levy pointed out in 1904 that the similarities in the writing of the two men appeared superficial. Albert Levy, Stirner and Nietzsche, Paris, 1904

- ^ R.A. Nicholls, "Beginnings of the Nietzsche Vogue in Germany", in Modern Philology, Vol. 56, No. 1, Aug., 1958, pp. 24–37

- ^ "Stirner, like Nietzsche, who was clearly influenced by him, has been interpreted in many different ways", Saul Newman, From Bakunin to Lacan: Anti-authoritarianism and the Dislocation of Power, Lexington Books, 2001, p. 56; "We do not even know for sure that Nietzsche had read Stirner. Yet, the similarities are too striking to be explained away." R. A. Samek, The Meta Phenomenon, p70, New York, 1981; Tom Goyens, (referring to Stirner's book The Ego and His Own) "The book influenced Friedrich Nietzsche, and even Marx and Engels devoted some attention to it." T. Goyens, Beer and Revolution: The German Anarchist Movement in New York City, p197, Illinois, 2007

- ^ "We have every reason to suppose that Nietzsche had a profound knowledge of the Hegelian movement, from Hegel to Stirner himself. The philosophical learning of an author is not assessed by the number of quotations, nor by the always fanciful and conjectural check lists of libraries, but by the apologetic or polemical directions of his work itself." Gilles Deleuze (translated by Hugh Tomlinson), Nietzsche and Philosophy, 1962 (2006 reprint, pp. 153–154)

- ^ O. Ewald, "German Philosophy in 1907", in The Philosophical Review, Vol. 17, No. 4, Jul., 1908, pp. 400–426; T. A. Riley, "Anti-Statism in German Literature, as Exemplified by the Work of John Henry Mackay", in PMLA, Vol. 62, No. 3, Sep., 1947, pp. 828–843; C. E. Forth, "Nietzsche, Decadence, and Regeneration in France, 1891-95", in Journal of the History of Ideas, Vol. 54, No. 1, Jan., 1993, pp. 97–117; see also Robert C. Holub's Nietzsche: Socialist, Anarchist, Feminist, an essay available online at the University of California, Berkeley website.

- ^ Robert C. Holub, Nietzsche: Socialist, Anarchist, Feminist Archived 2007-06-21 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "The life of Émile Armand (1872–1963) spanned the history of anarchism. He was influenced by Leo Tolstoy and Benjamin Tucker, and to a lesser extent by Whitman and Emerson. Later in life, Nietzsche and Stirner became important to his way of thinking."Introduction to The Anarchism of Émile Armand by Émile Armand

- ^ Rama, Carlos M. (December 24, 1990). El Anarquismo en América Latina. Fundacion Biblioteca Ayacuch. ISBN 9789802761173 – via Google Books.

- ^ PANCLASTA, Biófilo (1928): Comprimidos psicológicos de los revolucionarios criollos. Periódico Claridad, Bogotá, Nº 52, 53, 54, 55 y 56.

- ^ a b "Reply to Brian Morris's review of "I Am Not A Man, I Am Dynamite!"". Anarchy: A Journal of Desire Armed. No. 70–71. Archived from the original on 2012-03-06. Retrieved 2011-12-08.

- ^ Miething, Dominique (2016-04-02). "Overcoming the preachers of death: Gustav Landauer's reading of Friedrich Nietzsche". Intellectual History Review. 26 (2): 285–304. doi:10.1080/17496977.2016.1140404. ISSN 1749-6977.

- ^ [1] Archived 2009-11-04 at the Wayback Machine Nationalism and Culture by Rudolf Rocker

- ^ Miething, Dominique F. (2016). Anarchistische Deutungen der Philosophie Friedrich Nietzsches: Deutschland, Großbritannien, USA (1890-1947). Nomos Verlagsgesellschaft mbH & Co. KG. doi:10.5771/9783845280127. ISBN 978-3-8452-8012-7.

- ^ a b "Living My Life". www.revoltlib.com. January 23, 2017.

- ^ a b c d e Goldman, Emma. "Anarchism and Other Essays" – via Wikisource.

- ^ ""Victims of Morality" by Emma Goldman". Archived from the original on 2001-02-20. Retrieved 2009-11-04.

- ^ Solomon, Robert C. (2001). From Rationalism to Existentialism: The Existentialists and Their Nineteenth Century Backgrounds. Rowman and Littlefield. p. 245. ISBN 0-7425-1241-X.

- ^ "Albert Camus (1913—1960)" Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- ^ "The Philosophy of anarchism".

- ^ "Immediatism by Hakim Bey". Archived from the original on December 5, 2009.

- ^ a b "The ideology of victimization" by Feral Faun

- ^ a b c d e "Anarchism and the politics of ressentiment" by Saul Newman

- ^ Lewis Call. Postmodern Anarchism. Lexington: Lexington Books. 2002.

- ^ Lewis Call. Postmodern Anarchism. Lexington: Lexington Books. 2002. Pg. 33

- ^ "Michel Onfray : le post anarchisme expliqué à ma grand-mère – mag elle aime". Archived from the original on November 22, 2009.

- ^ "qu'il considère comme une révolte nietzschéenne pour avoir mis fin à la Vérité "Une", révélée, en mettant en évidence la diversité de vérités, pour avoir fait disparaître les idéaux ascétiques chrétiens et fait surgir de nouvelles possibilités d'existence."Michel Onfray : le post anarchisme expliqué à ma grand-mère Archived 2009-11-22 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ De la sagesse tragique - Essai sur Nietzsche (Poche) de Michel Onfray (Auteur)

- ^ Seyferth, Peter (2021). "Review of Dominique F. Miething, Anarchistische Deutungen der Philosophie Friedrich Nietzsches (1890–1947), Baden-Baden: Nomos, 2016; 533pp; ISBN 9783848737116". Anarchist Studies. 29 (1): 118–119.

External links

- "Nietzsche and the Anarchists" by Spencer Sunshine

- I Am Not A Man, I Am Dynamite! Friedrich Nietzsche and the Anarchist Tradition. editor John Moore as editor, with Spencer Sunshine. Many articles by various authors about the relationship and new possibilities of it between anarchism and Nietzsche.

- "Anarchism and the politics of ressentiment" by Saul Newman

- "Nietzsche in the streets" by Ruud Kaulingfreks

- Nietzsche and Anarchy by Shahin