Archbishop of Uppsala

Archbishop of Uppsala | |

|---|---|

| Archbishopric | |

| lutheran | |

Coat of arms | |

| Location | |

| Country | Sweden |

| Residence | Archbishop's Palace, Uppsala |

| Information | |

| Established | 1164 |

| Archdiocese | Uppsala |

| Cathedral | Uppsala Cathedral |

| Website | |

| svenskakyrkan | |

The Archbishop of Uppsala (spelled Upsala until the early 20th century) has been the primate of Sweden in an unbroken succession since 1164, first during the Catholic era, and from the 1530s and onward under the Lutheran church.

Historical overview

There have been bishops in Uppsala from the time of Swedish King Ingold the Elder in the 11th century. They were governed by the archbishop of Hamburg-Bremen until Uppsala was made an archbishopric in 1164. The archbishop in Lund (which at that time belonged to Denmark) was declared primate of Sweden, meaning it was his right to select and ordain the Uppsala archbishop by handing him the pallium. To gain independence, Folke Johansson Ängel in 1274 went to Rome and was ordained directly by the pope. This practice was increasing, so that no Uppsala archbishop was in Lund after Olov Björnsson, in 1318. In 1457, the archbishop Jöns Bengtsson (Oxenstierna) was allowed by the pope to declare himself primate of Sweden.

Uppsala (then a village) was originally located a couple of miles to the north of the present city, in what is today known as Gamla Uppsala (Old Uppsala). In 1273, the archbishopric, together with the relics of King Eric the Saint, was moved to the market town of Östra Aros, which from then on is named Uppsala.

In 1531, Laurentius Petri was chosen by King Gustav I of Sweden (Vasa) to be archbishop, taking that privilege from the pope and in effect making Sweden Protestant. The archbishop was then declared primus inter pares i.e. first among equals. The archbishop is both bishop of his diocese and Primate of Sweden; he has however no more authority than other bishops, although in effect his statements have a more widespread effect. In 1990, the Archbishop of Uppsala was aided in the diocese by a bishop of Uppsala. Karin Johannesson is the current (2022) Bishop of Uppsala.

Notable archbishops

The labours of the archbishops extended in all directions. Some were zealous pastors of their flocks, such as Jarler and others; some were distinguished canonists, such as Birger Gregerson (1367–83) and Olof Larsson (1435-8); others were statesmen, such as Jöns Bengtsson Oxenstjerna (d. 1467), or capable administrators, such as Jacob Ulfsson Örnfot, who was distinguished as a prince of the Church, royal councillor, patron of art and learning, founder of the University of Upsala and an efficient helper in the introduction of printing into Sweden. There were also scholars, such as Johannes Magnus (died 1544), who wrote the "Historia de omnibus Gothorum sueonumque regibus" and the "Historia metropolitanæ ecclesiæ Upsaliensis", and his brother Olaus Magnus (d. 1588), who wrote the "Historia de gentibus septentrionalibus" and who was the last Catholic Archbishop of Upsala.[1]

The archbishops and secular clergy found active co-workers among the regular clergy (i.e. religious orders). Among the orders represented in Sweden were the Benedictines, Cistercians, Dominicans, Franciscans, Brigittines (with the mother-house at Wadstena) and Carthusians. A Swedish Protestant investigator, Carl Silfverstolpe, wrote: "The monks were almost the sole bond of union in the Middle Ages between the civilization of the north and that of southern Europe, and it can be claimed that the active relations between our monasteries and those in southern lands were the arteries through which the higher civilization reached our country."[1]

See Birger Gregersson (1366–83; hymnist and author), Nils Ragvaldsson (1438–48; early adherent of Old Norse mythology), Jöns Bengtsson (Oxenstierna) (1448–67; King of Sweden), Jakob Ulfsson (1470–1514; founder of Uppsala University), Gustav Trolle (1515–21; supporter of the Danish King), Johannes Magnus (1523-26: wrote an imaginative Scandianian Chronicle), Laurentius Petri (1531–73; main character behind the Swedish Lutheran reformation), Abraham Angermannus (1593–99; controversial critic of the King), Olaus Martini (1601–09), Petrus Kenicius (1609–36), Laurentius Paulinus Gothus (1637–46; astronomer and philosopher of Ramus school), Johannes Canuti Lenaeus (1647–69; aristotelean and logician), Erik Benzelius the Elder (1700–09; highly knowledgeable), Haquin Spegel (1711–14; public educator), Mattias Steuchius (1714–30), Uno von Troil (1786–1803; politician), Jakob Axelsson Lindblom (1805–19), Johan Olof Wallin (1837–39; beloved poet and hymnist), Karl Fredrik af Wingård (1839–51; politician), Henrik Reuterdahl (1856–70) Anton Niklas Sundberg (1870–1900; outspoken and controversial) and Nathan Söderblom (1914–1931; Nobel Prize winner).[note 1]

Earliest bishops

The first written mention of a bishop at Uppsala is from Adam of Bremen's Gesta Hammaburgensis ecclesiae pontificum that records in passing Adalvard the Younger appointed as the bishop for Sictunam et Ubsalam in the 1060s.[2] Swedish sources never mention him either in Sigtuna or Uppsala.

The medieval Annales Suecici Medii Aevi[3][4] and the 13th century legend of Saint Botvid[5][6][7] mention some Henry as the Bishop of Uppsala (Henricus scilicet Upsalensis) in 1129, participating in the consecration of the saint's newly built church.[8] He is apparently the same Bishop Henry who died at the Battle of Fotevik in 1134, fighting along with the Danes after being banished from Sweden. Known from the Chronicon Roskildense written soon after his death and from Saxo Grammaticus' Gesta Danorum from the early 13th century, he had fled to Denmark from Sigtuna. Also he is omitted from, or at least redated in, the first list of bishops made in the 15th century.[9] In this list, the first bishop at Uppsala was Sverinius (Siwardus?), succeeded by Nicolaus, Sveno, Henricus and Kopmannus. With the exception of Henricus, the list only mentions their names.[8][10]

Archbishops before the Reformation

This section needs editing to comply with Wikipedia's Manual of Style. (November 2015) |

12th century

Johannes was ordained by the Archbishop of Lund, Absalon by November 1185. In 1187, a ship from the pagan Estonia entered Mälaren, a lake close to Uppsala, on a plundering expedition. It sailed to Sigtuna, a prosperous city at that time, and plundered it. On its way back, barricades were set up at the only exit point at Almarestäket to prevent the ship from escaping. Johannes was there also. As the ship struggled to pass through, Johannes were among those killed.

- 1187–1197 Petrus.

He was ordained by Absalon. Sweden got a new king, Sverker II of Sweden in 1196, who was related to the Danish Royal Court, whereby Absalon extended his authority over Sweden. When Petrus in 1196 elected three bishops, Absalon requested that the pope decide since the bishops were the sons of other priests, and this was not allowed by papal decree. He also mentioned that several Swedish bishops refused to travel to his synods. Absalon was an authoritative person whom the pope trusted and gave him rights, but by the time the message reached Uppsala Petrus had already died.

13th century

- 1198–1206 Olov Lambatunga.

In 1200, Pope Innocent III demanded that Church estate be free from the king's taxes and that clerics be judged only by bishops and prelates, and not civil courts and judges. This was a step in the separation between worldly and spiritual matters, which the Swedish Church had not yet taken. Innocent also demanded that Olov dismiss the two bishops ordained by Petrus.

When Uppsala burnt in 1204, Olov's pallium was burnt and he sent a request to Innocent III for a new one to be made.

- 1207–1219 Valerius.

Valerius was most likely the son of a church man – and the Archbishop of Lund appealed the election to Rome. The pope allowed a dispensation for Valerius on the grounds that there was no other suitable candidate and because Valierus was known as a learned man with good customs and virtues.

Valerius joined sides with the King Sverker II of Sweden who belonged to the House of Sverker. The House of Sverker was one of the antagonists in a civil war that had been going on and off since 1130. In 1208 the opposing side, the House of Eric, besieged the capital Stockholm; Sverker and Valierus fled to Denmark.

Sverker gathered a small army in Denmark and tried to conquer Sweden but was killed. Valerius then decided to accept King Eric X's authority, and as a result was allowed to return to Uppsala, where he crowned Eric X in 1210. Pope Innocent III sent a letter to Valerius where he proclaimed the procedure to be unauthorised and unlawful, but it seems to have had little impact.

- 1219(1224)-1234 Olov Basatömer. N/A

- 1236–1255 Jarler

He was one of the first known Swedish students at the University of Paris. As archbishop, he established several clerical regulations.

- 1255–1267 Lars (Laurentius).

Lars was recruited from the recently established Franciscan monastery in Enköping and was most likely a foreigner. The Pope expressed trust in the recently crowned Swedish monarch Birger Jarl who, unlike his predecessors, had promised to support the Church by granting it freedom from taxes and establish missionaries to yet un-Christianised parts – or parts who had returned to paganism – specifically Finland and the Baltic states.

But this promise was not realised because of the shaky political situation in Sweden. There was an ongoing struggle for power, which eventually forced the antagonists to tax Church property in order to support the war.

Lars tried to impose clerical celibacy, which still had not been enforced in Sweden because the low population figures in Sweden required priests to marry and have children. In 1258 Lars sent Pope Alexander IV a request that married clergy not be excommunicated, a request which indicates married clergy were not uncommon.

Also in 1258 the move of the archdiocese to its present location was decided, but it would not take effect for another decade.

- 1267–1277 Folke Johansson Ängel (Fulco Angelus).

Folke belonged to the influential family Ängel, which used the Archangel Gabriel as a heraldic charge.

He was, for unclear reasons, not ordained until 1274. Civil disturbances may have been a cause, but also the reluctance of the cathedral chapter to be under the authority of Lund. In 1274, Folke ignored the Primate of Lund by travelling to Rome and getting ordained by Pope Gregory X himself.

Folke's most important contribution was to commission the moving of the episcopal see from its old location to its present location. At his death he was one of the first to be buried in Uppsala Cathedral.[11]

- 1277–1281 Jakob Israelsson

Was from the same family as his predecessor. Little else is known about him.

- 1281–1284 Johan Odulfsson

Not ordained. Little is known about him.

- 1285–1289 Magnus Bosson.

Little is known about him.

- 1289–1291 Johan.

Had served as prior at the Sigtuna monastery and Bishop of Åbo. Died in Avignon while travelling to Rome to receive the pallium.

14th century

- 1292–1305 Nils Allesson (Nicolaus Allonius).

He studied at the University of Paris in 1278. After returning to Sweden, he became deacon in Uppsala in 1286 and was elected archbishop in 1292. As Nils Allesson was the son of a priest, the cathedral chapter in Lund, Denmark - the primate over Uppsala - appealed the election to the pope. Nils travelled to Rome in 1295 to meet the Pope Boniface VIII and defend his case, which was eventually accepted.

Nils was known as a vigorous archbishop. He founded and supervised institutions for safety and order around the archdiocese, such as accommodations for travellers.[12]

- 1308–1314 Nils Kettilsson

Little is known about him.

- 1315–1332 Olov Björnsson (Olov the Wise; Olavus sapiens).

Under his time the chapter in Uppsala stopped accepting Archbishop of Lund as primate, and Olov was to be the last Uppsala archbishop to be ordained there.[13]

- 1332–1341 Petrus Filipsson (Petrus Philippi).

He came from a smaller town in Uppland, the son of the knight Filip Finnvedson, one of the most important men in Uppland (the land of Uppsala). Petrus held various clerical offices until he was elected archbishop. Following the election he travelled to Avignon, the residence of Pope John XXII, to be ordained as bishop.

He had a strained relationship with the Franciscan order. At the request of Pope Benedict XII, Paul, Archbishop of Nidaros (now Trondheim) in Norway, was to make a judgement on the matter, and this led to a settlement between the two parties in 1339.

In 1341 Petrus died and was buried in Sigtuna's Dominican Order church which today is called Mariakyrkan.[14]

- 1341–1351 Hemming Nilsson.

At the death of Petrus, Pope Benedict XII wished to occupy the archbishop's seat through commission, but following Hemming's election by the cathedral chapter, Hemming travelled to Avignon and persuaded Benedict to ordain him bishop.

During his time, he helped in the political world, made a visitation through Norway and established Uppsala ecclesiastical records. His last will shows that he was also quite wealthy.[15]

- 1351–1366 Petrus Torkilsson (Petrus Tyrgilli; died 19 October 1366).

The first mention of him is from 1320, when he was vicar in Färentuna. He was chancellor of the King Magnus II of Sweden in 1340 and continued to support him during through the 1360s when Sweden was in a civil war.

In 1342 he was appointed Bishop of Linköping, where he assisted the building of the Linköping Cathedral. He was assessor during King Magnus monetary transactions, among them the repayment of a loan Magnus hade made from the Church. After the new King Albert of Sweden took power, Petrus supported him as well.

- 1366–1383 Birger Gregersson.

Was known as a vigorous archbishop. He was also a supporter of the Swedish, highly revered, Saint Birgitta (1303–1373), and wrote a biography of her. He also wrote in honour of her and of Saint Botvid, another Swedish saint. As a writer, he has a prominent place in early Swedish literature.[16]

- 1383–1408 Henrik Karlsson (Henricus Caroli).

Was also friends with Saint Birgitta, in Rome and took part in the important political decisions during his years as archbishop, such as the Kalmar Union in 1397.

Had a good economical skill, was a wealthy man, and acquired many farms for the Church. At his death, he left them to the cathedral chapter, but Queen Margaret is said to have taken them in possession instead, which marked the beginning of disputes between the chapter and the states in the union (which lasted until 1520).[17]

15th century

- 1408–1421 Jöns Gerekesson (Johannes Gerechini)

Jöns originated the influential Danish family Lodehat. His uncle was bishop of Roskilde and a former chancellor of the Queen. Jöns himself became, thanks to his family's Royal connection, chancellor to the King of Scandinavia, Eric of Pomerania.

At the death of the Archbishop Henrik, King Eric appointed Jöns, who had no connection to Uppsala, as new archbishop without regards to the candidates of the chapter.

During his time, Jöns paid little respect to the duties of archbishop. He embezzled Church property and mistreated Church officials. Eventually, the chapter complained to the Pope, who conducted an investigation and dismissed Jöns Gereksson in 1421.

- 1421–1432 Johan Håkansson (Johannes Haquini)

Was originally a monk at Vadstena monastery. As archbishop, he freed clericals of taxation, and built a permanent house for the archbishop.

- 1432–1438 Olov Larsson (Olaus Laurentii)

- 1433–1434 Arnold of Bergen (unofficial) (Arend in Norwegian; died 1434) was bishop of Bergen, Norway, and was never ordained as archbishop.

When Olaus Laurentii was elected by the Chapter to become Archbishop of Uppsala and Sweden, the Swedish King Eric of Pomerania was displeased because he was not consulted and therefore decided that Arnold of Bergen should become archbishop in 1433 while Olaus Laurentii was in Rome to be ordained. Arnold moved into the archbishopseat in Uppsala despite protests from the chapter.

The quarrels were resolved when Arnold died in 1434; then the king decided to accept Olaus Laurentii who had just returned from Rome.[18]

- 1438–1448 Nils Ragvaldsson (Nicolaus Ragvaldi)

- 1448–1467 Jöns Bengtsson (Oxenstierna)

- 1468–1469 Tord Pedersson (Bonde) (not ordained)

- 1469–1515 Jakob Ulvsson

- 1515–1517 and 1520–1521 Gustav Trolle

Gustav Eriksson Trolle (1488–1533) was a controversial person. He was in dispute with the king, since he was a supporter of the Danish King Christian II. In 1515 he was removed from office, but barricaded himself in the archbishop's mansion/fortress at Almarestäket, until an assembly of chancellors ordered its destruction in 1517. In 1520, Danish King Christian conquered Swedish territory, and Trolle was reinstated and deeply involved in Stockholm Bloodbath where he led the trial that found his political opponents guilty of heresy and he and King Christian II had them executed (among them the father of the future King Gustav Vasa). However, King Christian's reign in Sweden lasted but one year, and in 1521 Trolle was forced to flee to Denmark to seek refuge.

When the Pope months later received news of the deposition of Trolle, he ordered the reigning Swedish King Gustav Vasa to reinstate Trolle, not realizing the severity of the matter. Being forced to have his father's murderer reinstated as archbishop, King Gustav Vasa in effect broke away from the Catholic tradition, making Sweden a Lutheran nation starting 1531.

Archbishops during the Reformation

- 1523–1544 Johannes Magnus

Johannes Magnus was the last Catholic archbishop of Sweden. He was selected to be archbishop in 1523, but the Pope deemed the disposal of Gustav Trolle unlawful and demanded that he be reinstated. The Swedish king, Gustav Vasa, therefore broke with the Catholic Church and himself ordained Johannes Magnus. But before long, Magnus expressed disapproval of Lutheran teachings, so Gustav Vasa sent him to Russia as a diplomat in 1526.

Gustav Vasa appointed a new archbishop, Laurentius Petri, in 1531, and Johannes realized that his time as archbishop was over. He travelled to Rome where he stayed for the rest of his life.[19]

- 1544–1557 Olaus Magnus

Brother of the previous, with whom he was in exile in Rome. After the death of his brother, Olaus was consecrated by the Pope in 1544, but he never returned home. He was the last Swedish archbishop to get papal consecration.

Staying in Rome, Olaus wrote several highly regarded works about Scandinavia that still interest readers today. He also had works by his brother Johannes published.

Archbishops after the Reformation

16th century

- 1531–1573 Laurentius Petri (Nericius)

He and his brother Olaus Petri were the main Protestant reformers in Sweden; while his brother was more energetic, Laurentius laid the theoretical foundation for the Swedish Church Ordinance 1571.

- 1575–1579 Laurentius Petri Gothus

Before becoming archbishop, Gothus appears to have been inclined towards King Johan III of Sweden's more Catholic viewpoint. He was for this reason ordained by the King in a Catholic ritual with all its apparatus, and wrote the introduction to the King's "red book". As the Jesuitic tendencies grew stronger in Sweden in the 1570s, he became more wary; he refused to support the views of the King any longer, and published Contra novas papistarum machinationes which, although it gives proper respect to the Church fathers, polemizes against the foundation of Catholicism and the Jesuits.

- 1583–1591 Andreas Laurentii Björnram

He was vicar in Gävle 1570 and is reported as one of the first priests to have used the King's "red book" in his sermons, which sparked the King's interest, and he subsequently appointed him archbishop after a four-year vacancy.

Björnram upset Church officials by declaring that the liturgy of the King was in accordance with the Apostles' Creed and that he supported it. Surprisingly, he nonetheless advocated the reading of Luther's works.

- 1593–1599 Abraham Angermannus

Angermannus first became known as a critic of the liturgy of King John, and the king had him put in jail in Åbo, Finland. He managed to escape back to Stockholm with the protection of influential friends, but he eventually had to flee to Germany, where he lived for 11 years. He visited the renowned universities there and wrote several books with Lutheran contents aimed at Swedish readers.

In 1593, the cathedral chapter of Uppsala elected him archbishop, and he moved back to Sweden. He was a harsh critic of Catholic remnants which were still adhered to in Sweden. In 1599, the king had had enough of him and prosecuted him. Angermannus was put in prison in Gripsholm, where he was forced to remain until his death in 1607.[20]

- 1599–1600 Nicolaus Olai Bothniensis (not ordained)

Like his predecessor Angermannus, Bothniensis was imprisoned for 1.5 years due to his resistance to John III's non-Lutheran liturgy.

In 1593 he became the first professor of theology at the Uppsala University. He died before being consecrated.

17th century

- 1601–1609 Olaus Martini (Olof Mårtensson)

Born 1557 in Uppsala. Educated first in Uppsala, then abroad. He was against the liturgy of King John III of Sweden. He was made archbishop owing to the support of Duke Charles (Charles IX of Sweden), although they later clashed because of their fundamentally different beliefs.

- 1609–1636 Petrus Kenicius

Born 1555. Was against the King's liturgy, and was imprisoned for a short time of 1589. Participated in the Uppsala Synod 1593. Was archbishop for a long time, into his old age.

- 1637–1646 Laurentius Paulinus Gothus

Born 1565. Was knowledgeable in several subjects, and was professor of astronomy and logistics at Uppsala University. Wrote several works on astronomy, astrology and theology.

- 1647–1669 Johannes Canuti Lenaeus

Professor of Logic, Hebrew and Greek. Wrote an influential book about the philosophy of Aristotle that revived interest in Aristotelianism and was used as a textbook for several years.

- 1670–1676 Lars Stigzelius

Professor of Logic at Uppsala where he supported Aristotelian philosophy against the adherents of Ramism. Was considered a highly learned man and was involved in various political and clerical tasks. As an archbishop he did not make any great contribution owing to his advanced age.

- 1677–1681 Johan Baazius the younger

- 1681–1700 Olov Svebilius, (Olaus Svebilius)

Commissioned the new Bible translation and revising the Swedish book of hymns. Published many works, most notably A simple explanation of Martin Luther's little catechism.

18th century

- 1700–1709 Erik Benzelius the elder

Benzelius took an important part in the various ecclesiastical committees active during the reigns of Charles XI and Charles XII, such as that concerning the new Church Law of 1686, the new hymn book of 1695 and the new Bible translation.

He was a typical representative of 17th-century Swedish Lutheran orthodoxy, careful not to deviate from established theological principles, and lacked originality in his writing. Nevertheless, he was a productive author of works in theology, and his work on church history was used as a textbook for the following century.[21]

- 1711–1714 Haquin Spegel (born Håkan Spegel; 14 June 1645 – 17 April 1714)

He was an important religious author and hymn writer. He held several bishop's seats before becoming archbishop.

- 1714–1730 Mathias Steuchius

- 1730–1742 Johannes Steuchius, (Johannes Steuch)

- 1742–1743 Erik Benzelius the younger

- 1744–1747 Jakob Benzelius

- 1747–1758 Henric Benzelius

- 1758–1764 Samuel Troilius

- 1764–1775 Magnus Beronius

- 1775–1786 Carl Fredrik Mennander

- 1786–1803 Uno von Troil

19th century

- 1805–1819 Jakob Axelsson Lindblom

- 1819–1836 Carl von Rosenstein (Carl Rosén von Rosenstein)

(Uppsala 13 May 1736 – 2 December 1836) was a member of the Swedish Academy. He belonged to the influential noble families von Rosén and Rosenstein.

He was knowledgeable in the classic languages, had an unusual knowledge of agriculture and was a member of all the Swedish Royal Academies at the time, except for the Academy of Arts. The academies he joined were: the Academy of Science and Literature (joined in 1807), Academy of Science (1808), the Academy of Literature History (1810), the Academy of Agriculture and Forestry (1818), the Swedish Academy (1819), the Scientific society in Uppsala (1820) and the Academy of Music (1822). He was regarded as a generous and social person, friendly, handsome and cheerful. [22]

- 1837–1839 Johan Olof Wallin (1779–1839), minister, orator, poet. He was a prolific writer, today best remembered for the hymns he wrote.

- 1839–1851 Carl Fredrik af Wingård

- 1852–1855 Hans Olov Holmström (15 October 1784 – 27 August 1855)

After acquiring his Master of Arts in philosophy and theology and becoming assistant professor in Latin at Uppsala University, he moved to Strängnäs where he was eventually appointed bishop in 1839. He was also an influential politician in the Swedish Riksdag from 1828 to his death.

He was known as a soft and gently person, and very firm in his beliefs.[23]

- 1856–1870 Henrik Reuterdahl (1795–1870)

Stemming from Malmö, he was orphaned early on and had to rely on others for his education and support. Despite this he managed to get a higher education at the Lund University in theology, philology and Church history, influenced by local academic dignitaries such as Erik Gustaf Geijer and the German Schleiermacher whose works were popular in Lund at the time.

He later published a comprehensive history of the Church in Sweden, and was a member of the Swedish Academy from 1852.[24]

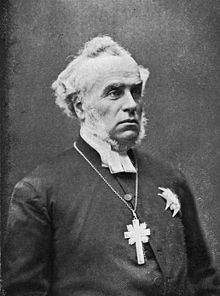

- 1870–1900 Anton Niklas Sundberg (27 May 1818 – 2 February 1900)

He acquired a philosophy doctor's degree in Uppsala, became dean and was ordained priest, and then undertook travel through Europe in 1849–50.

He was known as a controversial person; very outspoken, no stranger to using strong language, despising hypocrisy, but he displayed a notable sense of wit and authority.[25]

20th century

- 1900–1913 Johan August Ekman

- 1914–1931 Nathan Söderblom, theologian and influential researcher into the history of religions; one of the key organizers of the modern Ecumenical movement.

- 1931–1950 Erling Eidem

- 1950–1958 Yngve Brilioth (12 July 1891 in Västra Ed, Kalmar County – died 27 April 1959 in Uppsala)

Was PhD in Uppsala and subsequently a dean and professor of philosophy and bishop of Växjö.

He wrote many international historical and theological books. For his contribution to the history of the Anglican Church, in 1942 he was awarded the Lambeth Cross, the highest award in the Anglican Church.

He used his deep historical knowledge when he was archbishop to take measures concerning the organisation, liturgy and methods of preaching; he furthermore had an international interest and was chairman of the Faith and Order commission.[26][27]

- 1958–1967 Gunnar Hultgren

(born 19 February 1902 in Eskilstuna; died 13 February 1991 in Uppsala.)

- 1967–1972 Ruben Josefson

(born 25 August 1907 in Svenljunga, Älvsborgs län; died 19 March 1972 in Uppsala.)

- 1972–1983 Olof Sundby (1917–1996)

He officiated at the marriage of present King Carl XVI Gustaf and Queen Silvia on 19 June 1976, in Storkyrkan in Stockholm.

- 1983–1993 Bertil Werkström (1928–2010)

- 1993–1997 Gunnar Weman (born 1932)

- 1997–2006 Karl Gustav Hammar (born 1943)

21st century

On 15 June 2014 Antje Jackelén became Archbishop of Uppsala and primate of the Church of Sweden. She is the first woman to hold that position.[28]

- 2006–2014 Anders Wejryd (born 1948)

- 2014–present Antje Jackelén (born 1955)

In June 2022, Bishop Martin Modéus was elected to succeed Jackelén upon her retirement on 30 October. If his election is confirmed, he will be inaugurated 4 December.[29]

See also

References

Notes

- ^ The list is inspired by a similar list in Nordisk familjebok, Uppsala stift. Has external link below.

Citations

- ^ a b Armfelt 1912.

- ^ Adam of Bremen 1876, scholia 94.

- ^ Paulsson 1974.

- ^ Karl Fredrik Wesén. "Sigtunaannalerna". Foteviken Museum. Archived from the original on 27 December 2007.

- ^ "Saint Botvid". New Catholic Dictionary. Archived from the original on 19 November 2008.

- ^ "St. Botvid". Holy Spirit Interactive. Archived from the original on 8 August 2007.

- ^ Schück 1952, pp. 178–187.

- ^ a b Rosén & Westrin 1908, pp. 695–696, Gamla Upsalla.

- ^ Heikkilä 2005, p. 60.

- ^ Annerstedt 1705.

- ^ Rosén & Westrin 1894, p. 528, Ängel.

- ^ Rosén & Westrin 1887, p. 1128, Nils Alleson.

- ^ Rosén & Westrin 1888, p. 209, Olov Björnsson.

- ^ Rosén & Westrin 1915, pp. 713–714, Petrus.

- ^ Rosén & Westrin 1909, p. 397, Hemming Nilsson.

- ^ Rosén & Westrin 1906, pp. 695–696, Birger Gregersson.

- ^ Rosén & Westrin 1909, p. 456, Henrik Karlsson.

- ^ Rosén & Westrin 1888, pp. 167–168, Olaus Laurentii.

- ^ Rosén & Westrin 1910, pp. 38–39, Johannes Magnus.

- ^ Rosén & Westrin 1904, pp. 56–57, Abrahamus Andreæ Angermannus.

- ^ Rosén & Westrin 1904b, pp. 1387–1389, Benzelius, Erik.

- ^ Rosén & Westrin 1916, pp. 56–57, Rosén von Rosenstein, Karl.

- ^ Rosén & Westrin 1909, p. 1015, Holström, Hans.

- ^ Rosén & Westrin 1916, pp. 30–31, Reuterdahl, Henrik.

- ^ Hofberg et al. 1906, p. 560, Sundberg, Anton Niklas.

- ^ Browning, Janowski & Jüngel 2007, p. 225, Brilioth, Yngve Torgny.

- ^ Martling n.d.

- ^ Lindahl 2015.

- ^ "Martin Modéus elected new Archbishop of the Church of Sweden | Svenska kyrkan".

Sources

- Adam of Bremen (1876). G. Waitz (ed.). Gesta Hammaburgensis Ecclesiae Pontificum [Deeds of the Bishops of Hamburg] (in Latin). Berlin.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Annerstedt, Claes, ed. (1705), Incerti scriptoris Sueci Chronicon primorum in ecclesia Upsalensi archiepiscoporum (in Latin), New York: Olaus Celsius Snr, retrieved 27 October 2020

- Armfelt, Carl Gustav (1912). . In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 15. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- Browning, Don S.; Janowski, Bernd; Jüngel, Eberhard (2007). Religion Past & Present. Vol. 2 : Bia-Chr. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-14608-2.

- Heikkilä, Tuomas (2005). Pyhän Henrikin legenda. Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura. ISBN 978-951-746-738-4.

- Hofberg, Herman; Heurlin, Frithiof; Millqvist, Viktor; Rubenson, Olof (1906). Svenskt biografiskt handlexikon (in Swedish). Vol. II. Stockholm: Albert Bonniers.

- Lindahl, Björn (6 March 2015). "The importance of gender equality in religious societies". Nordic Labour Journal. Retrieved 27 October 2020.

- Martling, Carl Henrik (n.d.). Kyrkohistoriskt Personlexikon.

- Paulsson, Göte (1974). Annales Suecici Medii Aevi. Volume 32 of Bibliotheca historica Lundensis. CWK Gleerup.

- Rosén, John; Westrin, Theodor, eds. (1887). Nordisk familjebok (in Swedish). Vol. 11 (1st ed.). Stockholm.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Rosén, John; Westrin, Theodor, eds. (1888). Nordisk familjebok (in Swedish). Vol. 12 (1st ed.). Stockholm.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Rosén, John; Westrin, Theodor, eds. (1894). Nordisk familjebok (in Swedish). Vol. 18 (1st ed.). Stockholm.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Rosén, John; Westrin, Theodor, eds. (1904). Nordisk familjebok (in Swedish). Vol. 1 (2nd ed.). Stockholm.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Rosén, John; Westrin, Theodor, eds. (1904b). Nordisk familjebok (in Swedish). Vol. 2 (2nd ed.). Stockholm.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Rosén, John; Westrin, Theodor, eds. (1906). Nordisk familjebok (in Swedish). Vol. 3 (2nd ed.). Stockholm.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Rosén, John; Westrin, Theodor, eds. (1908). Nordisk familjebok (in Swedish). Vol. 9 (2nd ed.). Stockholm.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Rosén, John; Westrin, Theodor, eds. (1909). Nordisk familjebok (in Swedish). Vol. 11 (2nd ed.). Stockholm.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Rosén, John; Westrin, Theodor, eds. (1910). Nordisk familjebok (in Swedish). Vol. 13 (2nd ed.). Stockholm.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Rosén, John; Westrin, Theodor, eds. (1915). Nordisk familjebok (in Swedish). Vol. 21 (2nd ed.). Stockholm.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Rosén, John; Westrin, Theodor, eds. (1916). Nordisk familjebok (in Swedish). Vol. 23 (2nd ed.). Stockholm.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Schück, Adolf (1952). "Den äldsta urkunden om svearikets omfattning". Fornvännen. Journal of Swedish Antiquarian Research (in Swedish): 178–187.

Further reading

- Rosén, John; Westrin, Theodor, eds. (1920). "Uppsala ärkestift". Nordisk familjebok (in Swedish). Vol. 30 (2nd ed.). Stockholm. pp. 1271–1273.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Rosén, John; Westrin, Theodor, eds. (1922). "Ärkebiskop". Nordisk familjebok (in Swedish). Vol. 33 (2nd ed.). Stockholm. pp. 1263–1265.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Rosén, John; Westrin, Theodor, eds. (1892). "Uppsala stift". Nordisk familjebok (in Swedish). Vol. 16 (1st ed.). Stockholm. pp. 1477–1478.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Nygren, Ernst (1953), Svenskt Biografiskt Lexikon, Stockholm

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Hansson, Klas (2014). Svenska kyrkans primas. Ärkebiskopsämbetet i förändring 1914–1990 [The Primate of the Church of Sweden. The Office of Archbishop in Transition 1914–1990] (Doctoral) (in Swedish). Uppsala: Acta Universitatis Upsaliensis, Studia Historico-Ecclesiastica Upsaliensia 47. urn:nbn:se:uu:diva-219366.

- Svea Rikes Ärkebiskopar, Uppsala, 1935