Duke of Normandy

In the Middle Ages, the duke of Normandy was the ruler of the Duchy of Normandy in north-western France. The duchy arose out of a grant of land to the Viking leader Rollo by the French king Charles the Simple in 911. In 924 and again in 933, Normandy was expanded by royal grant. Rollo's male-line descendants continued to rule it until 1135, and cognatic descendants ruled it until 1204. In 1202 the French king Philip II declared Normandy a forfeited fief and by 1204 his army had conquered it. It remained a French royal province thereafter, still called the Duchy of Normandy, but only occasionally granted to a duke of the royal house as an appanage.

Despite both the 13th century loss of mainland Normandy, the renunciation of the title by Henry III of England in the Treaty of Paris (1259),[1] and the extinction of the duchy itself in modern-day, republican France, in the Channel Islands the monarch of the United Kingdom is regardless still sometimes informally referred to by the title "Duke of Normandy". This is the title used whether the monarch is a king or a queen.

History of the title

[edit]There is no record of Rollo holding or using any title. His son and grandson, Duke William I and Duke Richard I, used the titles "count" (Latin comes or consul) and "prince" (princeps).[2] Prior to 1066, the most common title of the ruler of Normandy was "Count of Normandy" (comes Normanniae) or "Count of the Normans" (comes Normannorum).[3] The title Count of Rouen (comes Rotomagensis) was never used in any official document, but it was used of William I and his son by the anonymous author of a lament (planctus) on his death.[4] Defying Norman pretensions to the ducal title, Adhemar de Chabannes was still referring to the Norman ruler as "Count of Rouen" as late as the 1020s. In the 12th century, the Icelandic historian Ari Thorgilsson in his Landnámabók referred to Rollo as Ruðu jarl (earl of Rouen), the only attested form in Old Norse, although too late to be evidence for 10th-century practice.[5] The late 11th-century Norman historian William of Poitiers used the title "Count of Rouen" for the Norman rulers down to Richard II.[citation needed] According to David C. Douglas, the title "Count of Rouen" (comes Rotomagensis) was never used in any official document.[6] Charters are usually a source of information about titles, but none exist for Normandy in the middle of the tenth century.[7]

The first official recorded use of the title duke (dux) is in an act in favour of the Abbey of Fécamp in 1006 by Richard II, Duke of Normandy. Earlier, the writer Richer of Reims had called Richard I a dux pyratorum, but which only means "leader of pirates" and was not a title. During the reign of Richard II, the French king's chancery began to call the Norman ruler "Duke of the Normans" (dux Normannorum) for the first time.[2] As late as the reign of Duke William II (1035–87), the ruler of Normandy could style himself "prince and duke, count of Normandy" as if unsure what his title should be.[3] The literal Latin equivalent of "Duke of Normandy", dux Normanniae, was in use by 1066,[8] but it did not supplant dux Normannorum until the Angevin period (1144–1204), at a time when Norman identity was fading.[9]

Richard I experimented with the title "marquis" (marchio) as early as 966, when it was also used in a diploma of King Lothair.[10] Richard II occasionally used it, but he seems to have preferred the title duke. It is his preference for the ducal title in his own charters that has led historians to believe that it was the chosen title of the Norman rulers. Certainly it was not granted to them by the French king. In the twelfth century, the Abbey of Fécamp spread the legend that it had been granted to Richard II by Pope Benedict VIII (ruled 1012–24). The French chancery did not regularly employ it until after 1204, when the duchy had been seized by the crown and Normandy lost its autonomy and its native rulers.[3]

The actual reason for the adoption of a higher title than that of count was that the rulers of Normandy began to grant the comital title to members of their own family. The creation of Norman counts subject to the ruler of Normandy necessitated the latter taking a higher title. The same process was at work in other principalities of France in the eleventh century, as the comital title came into wider use and thus depreciated. The Normans nevertheless kept the title of count for the ducal family and no non-family member was granted a county until Helias of Saint-Saëns was made Count of Arques by Henry I in 1106.[3]

From 1066, when William II conquered England, becoming King William I, the title Duke of Normandy was often held by the King of England. In 1087, William died and the title passed to his eldest son, Robert Curthose, while his second surviving son, William Rufus, inherited England. In 1096, Robert mortgaged Normandy to William, who was succeeded by another brother, Henry I, in 1100. In 1106, Henry conquered Normandy. It remained with the King of England down to 1144, when, during the civil war known as the Anarchy, it was conquered by Geoffrey Plantagenet, the Count of Anjou. Geoffrey's son, Henry II, inherited Normandy (1150) and then England (1154), reuniting the two titles. In 1202, King Philip II of France, as feudal suzerain, declared Normandy forfeit and by 1204 his armies had conquered it. Henry III finally renounced the English claim in the Treaty of Paris (1259).

Thereafter, the duchy formed an integral part of the French royal demesne. The kings of the House of Valois started a tradition of granting the title to their heirs apparent. The title was granted four times (1332, 1350, 1465, 1785) between the French conquest of Normandy and the dissolution of the French monarchy in 1792. The French Revolution brought an end to the Duchy of Normandy as a political entity, by then a province of France, and it was replaced by several départements.

List of dukes of Normandy (911–1204)

[edit]House of Normandy (911–1135)

[edit]| Portrait | Name

Lifespan |

Reign | Marriage(s) | Relation to predecessor(s) | Other titles |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Rollo

(Rollon) c. 835/870 – 928/933 |

911–928 | (1) Poppa of Bayeux

one son and one daughter (2) Gisela of France existence uncertain |

Granted by the Treaty of Saint-Clair-sur-Epte | No official title(s).[2] |

|

William I

Longsword (Gllâome I) 893 – 17 December 942 |

927–17 December 942 | (1) Sprota

one son no issue (m. before 940) |

Son of Rollo | |

|

Richard I

the Fearless (R'chard Sans-Peur) 28 August 932 – 20 November 996 |

17 December 942 – 20 November 996 | (1) Emma of Paris

no issue (m.960; died 968) (2) Gunnor seven children (m. c. 989) |

Son of William I | Called Count of Normandy in primary sources[11] |

|

Richard II

the Good (R'chard le Bouon) 978 – 28 August 1026 |

996–1026 | (1) Judith of Brittany

six children (m.1000; died 1017) two children (m.1017) |

Son of Richard I | |

|

Richard III

(R'chard III) 997/1001 – 6 August 1027 |

28 August 1026 – 6 August 1027 | never married | Son of Richard II | |

|

Robert I

the Magnificent (Robèrt le Magnifique) 22 June 1000 – 1–3 July 1035 |

1027–1035 | never married

Had extramarital relationship to Herleva one son and one daughter |

Brother of Richard III | |

|

William II

the Conqueror (Gllâome le Contchérant) 3 July 1035 – 9 September 1087 |

c. at least 1036 – 9 September 1087 | Matilda of Flanders

ten children (m.1051/2; died 1083) |

Son of Robert I | King of England |

|

Robert II

Curthose (Robèrt Courtheuse) c. 1051 – 3 February 1134 |

9 September 1087 – 1106 | Sybilla of Conversano

one son (m.1100; died 18 March 1103) |

Oldest son of William II | |

|

Henry I

Beauclerc (Henri I Beauclerc) c. 1068 – 1 December 1135 |

1106 – 1 December 1135 | (1) Matilda of Scotland

one son and one daughter (m.1100; died 1118) no issue (m. 1121) |

Brother of Robert II

Son of William II |

King of England |

|

William (III)

Clito (Gllâome Cliton) 25 October 1102 – 28 July 1128 (Claimant) |

1106–1128 | (1) Sibylla of Anjou

no issue (m. 1123; annulled 1124) no issue (m. 1127; died 1128) |

Eldest son of Robert Curthose | Count of Flanders |

House of Blois (1135–1144)

[edit]| Portrait | Name

Lifespan |

Reign | Marriage(s) | Relationship with predecessor(s) | Other titles |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Stephen

(Étienne) 1092/1096 – 25 October 1154 |

1135–1144 | Matilda I, Countess of Boulogne five children (m. 1136; died 1152) |

Grandson of William II through Adela of Normandy

Nephew of Henry I |

King of England |

House of Plantagenet (1144–1204)

[edit]| Portrait | Name

Lifespan |

Reign | Marriage(s) | Relationship with predecessor(s) | Other titles | Other Details |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Geoffrey the Handsome (Geffrai le Biau) 24 August 1113 – 7 September 1151 |

1144–1150 | Matilda of England three children (m. 1128) |

Son-in-law of Henry I | Count of Anjou | Conquered Normandy from Stephen I. |

|

Henry II Curtmantle (Henri Court-manté) 5 March 1133 – 6 July 1189 |

1150 – 6 July 1189 | Eleanor of Aquitaine eight children (m. 1152) |

Son of Geoffrey

First cousin, once removed of Stephen |

King of England | |

| Henry II named his son, Henry the Young King (1155–1183), as co-ruler with him but this was a Norman custom of designating an heir, and the younger Henry did not outlive his father and rule in his own right, so he is not counted as a duke on lists of dukes. | ||||||

|

Richard IV the Lionheart (R'chard le Quor de Lion) 8 September 1157 – 6 April 1199 |

3 September 1189 – 6 April 1199 | Berengaria of Navarre no issue (m. 1191) |

Son of Henry II | King of England | |

|

John Lackland (Jean sans Terre) 24 December 1166 – 1204 |

1199 – 1204 | (1) Isabella, Countess of Gloucester

no issue (m. 1189; annulled 1199) (2) Isabella, Countess of Angoulême five children (m. 1200) |

Brother of Richard IV

Son of Henry II |

King of England Lord of Ireland |

Lost mainland Normandy in 1204 |

French province (1204–1792)

[edit]In 1204, the King of France confiscated the Duchy of Normandy (with only the Channel Islands remaining under English control) and subsumed it into the crown lands of France. Thereafter, the ducal title was held by several French princes.

In 1332, King Philip VI gave the Duchy in appanage to his son John, who became king John II of France in 1350. He in turn gave the Duchy in appanage to his son Charles, who became king Charles V of France in 1364. In 1465, Louis XI, under constraint, gave the Duchy to his brother Charles de Valois, Duke of Berry. Charles was unable to hold the Duchy and in 1466 it was again subsumed into the crown lands and remained a permanent part of them. The title was conferred on a few junior members of the French royal family before the abolition of the French monarchy in 1792.

- John (son of King Philip VI, later King John II of France), 1332–1350.

- Charles (son of John II of France, later King Charles V of France), 1350–1364

- Charles (brother of Louis XI of France, also Duke of Berry), 1465–1466

- James, Duke of York, later King James II of England. On 31 December 1660, a few months after the restoration of Charles II to the thrones of England and Scotland, King Louis XIV proclaimed Charles's younger brother, James, Duke of York, "Duke of Normandy". This was probably done as a political gesture of support.[12]

- Louis-Charles (son of Louis XVI, later Dauphin 1789–1791 and titular King Louis XVII 1792–1795), 1785–1792.

Modern usage

[edit]

In the Channel Islands, the British monarch is known informally as the "Duke of Normandy", irrespective of whether or not the holder is male (as in the case of Queen Elizabeth II who was known by this title).[13] The Channel Islands are the last remaining part of the former Duchy of Normandy to remain under the rule of the British monarch. Although the English monarchy relinquished claims to continental Normandy and other French claims in 1259 (in the Treaty of Paris), the Channel Islands (except for Chausey under French sovereignty) remain Crown dependencies of the British throne.

The British historian Ben Pimlott noted that while Queen Elizabeth II was on a visit to mainland Normandy in May 1967, French locals began to doff their hats and shout "Vive la Duchesse!", to which the Queen supposedly replied "Well, I am the Duke of Normandy!"[14][failed verification]

However, the king is customarily referred to as "The Duke of Normandy", the title used by the islanders, especially during their loyal toast, where they say, "The Duke of Normandy, our King", or "The King, our Duke", "L'Rouai, nouotre Duc" or "L'Roué, note Du" in Norman (Jèrriais and Guernésiais respectively), or "Le Roi, notre Duc" in Standard French, rather than simply "The King", as is the practice in the United Kingdom.[15][16]

...Queen Elizabeth II is often referred to by her traditional and conventional title of Duke of Normandy. However [...] she is not the Duke in a constitutional capacity and instead governs in her right as Queen [...] This notwithstanding, it is a matter of local pride for monarchists to treat the situation otherwise: the Loyal Toast at formal dinners is to 'The Queen, our Duke' rather than 'Her Majesty, the Queen' as in the UK."[16]

The title 'Duke of Normandy' is not used in formal government publications, and, as a matter of Channel Islands law, does not exist.[17][16]

Statue

[edit]A statue of the first seven dukes was erected in Falaise in Normandy in the 19th century.[18] It depicts William the Conqueror, the Duke of Normandy and later King of England, on a horse, and is surrounded by statues of his six predecessors.

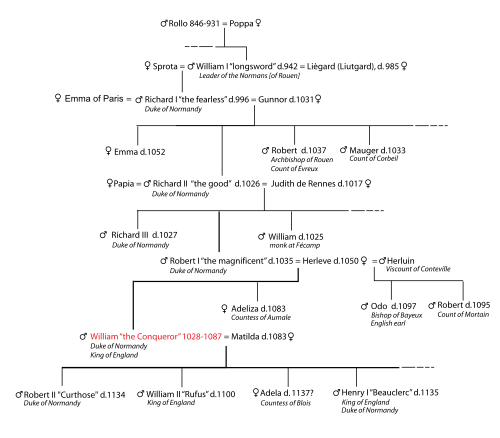

Family trees

[edit]| House of Normandy Family tree | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

References

[edit]- ^ "The historical background and the 'Lands of the Normans'". The Digital Humanities Institute. University of Sheffield.

- ^ a b c Marjorie Chibnall, The Normans (Blackwell, 2006), pp. 15–16. According to her, "it is even doubtful if Rollo had any title."

- ^ a b c d David Crouch, The Image of Aristocracy in Britain, 1000–1300 (Taylor and Francis, 1992), pp. 40–41.

- ^ Foley, Liam (17 December 2021). "December 17, 942: Death of William I Longsword of Normandy". European Royal History ~ Exploring the Monarchs of Europe. Retrieved 7 January 2024.

- ^ David C. Douglas, "The Earliest Norman Counts", The English Historical Review, 61, 240 (1946): 129–56.

- ^ David C. Douglas, "The Earliest Norman Counts", The English Historical Review, 61, 240 (1946):130

- ^ Elizabeth van Houts (ed.), The Normans in Europe (Manchester University Press, 2000), p. 41, n. 58.

- ^ George Beech, "The Participation of Aquitanians in the Conquest of England 1066–1100", in R. Allen Brown, ed., Anglo-Norman Studies IX: Proceedings of the Battle Conference, 1986 (Boydell Press, 1987), p. 16.

- ^ Nick Webber, The Evolution of Norman Identity, 911–1154 (Boydell Press, 2005), p. 178.

- ^ David Crouch, The Normans: The History of a Dynasty (Hambledon Continuum, 2002), p. 19.

- ^ David C. Douglas, "The Earliest Norman Counts", The English Historical Review, 61, 240 (1946):130

- ^ Weir, Alison (1996). 258. Britain's Royal Families: The Complete Genealogy. Revised Edition. Random House, London. ISBN 0-7126-7448-9.

- ^ "Crown Dependencies". The Royal Household. Archived from the original on 11 July 2021. Retrieved 10 July 2021.

- ^ The Queen: Elizabeth II and the Monarchy, p. 314, at Google Books

- ^ "The Loyal Toast". Debrett's. 2016. Archived from the original on 7 March 2016. Retrieved 25 January 2016.

In Jersey the toast of 'The Queen, our Duke' (i.e. Duke of Normandy) is local and unofficial, and used when only islanders are present. This toast is not used in the other Channel Islands.

- ^ a b c The Channel Islands, p. 11, at Google Books

- ^ Matthews, Paul (1999). "Lé Rouai, Nouot' Duc" (PDF). Jersey and Guernsey Law Review. 1999 (2).

- ^ Base Mérimée: Statue de Guillaume le Conquérant, Ministère français de la Culture. (in French)

Further reading

[edit]- Helmerichs, Robert. "Princeps, Comes, Dux Normannorum: Early Rollonid Designators and their Significance". Haskins Society Journal, 9 (2001): 57–77.