Glory (1989 film)

| Glory | |

|---|---|

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Edward Zwick |

| Screenplay by | Kevin Jarre |

| Produced by | Freddie Fields |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Freddie Francis |

| Edited by | Steven Rosenblum |

| Music by | James Horner |

Production company | Freddie Fields Productions |

| Distributed by | TriStar Pictures |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 122 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $18 million[1] |

| Box office | $26.8 million[2] |

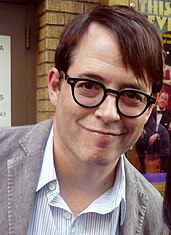

Glory is a 1989 American war film directed by Edward Zwick starring Matthew Broderick, Denzel Washington, Cary Elwes, and Morgan Freeman. The screenplay was written by Kevin Jarre, based on the personal letters of Colonel Robert Gould Shaw, the 1965 novel One Gallant Rush by Peter Burchard (reissued in 1990 after the movie), and Lay This Laurel (1973) by Lincoln Kirstein. The end credits are superimposed on photos of the monument to the 54th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry on Boston Common.

The film is about one of the first military units of the Union Army, during the American Civil War, to consist entirely of African-American men (except for its officers), as told from the point of view of Colonel Shaw, its white commanding officer. The regiment is known especially for its heroic actions at Fort Wagner.

Glory was nominated for five Academy Awards and won three, including one for Denzel Washington for Best Supporting Actor for his portrayal of Private Silas Tripp. It won many other awards from, among others, the British Academy of Film and Television Arts, the Golden Globe Awards, the Kansas City Film Critics Circle, the Political Film Society, and the NAACP.

The film was co-produced by TriStar Pictures and Freddie Fields Productions, and distributed by Tri-Star Pictures in the United States. It premiered in limited release in the US on December 14, 1989, and in wide release on February 16, 1990, making $26,828,365 on an $18 million budget. The soundtrack, composed by James Horner and performed in part by Boys Choir of Harlem, was released on January 23, 1990. The home video was distributed by Sony Pictures Home Entertainment. On June 2, 2009, a widescreen Blu-ray version, featuring the director's commentary and deleted scenes, was released.

Plot

During the American Civil War, Captain Robert Shaw, injured at Antietam, is sent home to Boston on medical leave. Shaw accepts a promotion to colonel commanding the 54th Regiment Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry, one of the first all-black regiments in the Union Army. He asks his friend, Cabot Forbes, to serve as his second in command, with the rank of major. Their first volunteer is another friend, Thomas Searles, a bookish, free African-American. Other recruits include John Rawlins, Jupiter Sharts, Silas Tripp, and a mute teenage drummer boy.

The men learn that, in response to the Emancipation Proclamation, the Confederacy has issued an order that all black soldiers will be returned to slavery. Black soldiers found in a Union uniform will be executed as well as their white officers. They are offered, but turn down, a chance to take an honorable discharge. They undergo rigorous training with Sergeant-Major Mulcahy, which Shaw realizes is to prepare them for the challenges they will face.

Tripp goes AWOL and is caught, Shaw orders him flogged in front of the troops. He learns that Tripp left to find shoes to replace his worn ones; his men are being denied supplies. He confronts the base's racist quartermaster on their behalf. Shaw also supports them in a pay dispute, as the Federal government pays black soldiers $10, not the $13 per month white soldiers earn. When the men begin tearing up their pay stubs in protest of the unequal treatment, Shaw tears up his own pay stub in support of their actions. In recognition of his leadership, Shaw promotes Rawlins to the rank of Sergeant-Major.

Once the 54th completes its training, they are transferred under the command of General Charles Harker. On the way to South Carolina they are ordered by Colonel James Montgomery to sack and burn Darien, Georgia. Shaw initially refuses to obey an unlawful order, but agrees under threat of having his troops taken away. He continues to lobby his superiors to allow his men to join the fight, as their duties to date have involved manual labor for which they are being mocked. Shaw finally gets the 54th into combat after he confronts Harker and threatens to report the illegal activities he has discovered. In their first battle at James Island, South Carolina, early success is followed by a confrontation with many casualties. The Confederates are defeated and retreat. During the battle, Thomas is wounded but saves Tripp. Shaw offers Tripp the honor of bearing the regimental flag in battle. He declines not believing the war will result in a better life for slaves.

General George Strong informs Shaw of a major campaign to secure a foothold at Charleston Harbor. This involves assaulting Morris Island and capturing Fort Wagner, whose only landward approach is a strip of open beach; a charge is certain to result in heavy casualties. Shaw volunteers the 54th to lead the charge. The night before the battle the black soldiers conduct a religious service, and several make emotional speeches to inspire the troops, and to ask for God's help. On their way to the attack, the 54th is cheered by the same Union troops who had scorned them earlier.

The 54th leads the charge on the fort suffering heavy casualties. At night the bombardment continues, forestalling progress. Attempting to encourage his men, Shaw is killed. Tripp lifts the flag rallying the soldiers to continue the charge. He is shot but holds up the flag until he dies. Forbes takes charge, and the soldiers are able to break through the fort's outer defenses. However, Charlie Morse is killed and Thomas is wounded. At the end of the battle it is implied that Forbes, Rawlins, Thomas, Jupiter, and the two Color Sergeants were killed by canister shot. The morning after the battle, the beach is littered with bodies of Union soldiers; the Confederate flag is raised over the fort. The dead Union soldiers are buried in single mass grave, with Shaw and Tripp's bodies next to each other.

Closing text reveals Fort Wagner was never taken by the Union Army. However, the courage demonstrated by the 54th resulted in the Union accepting thousands of black men for combat, and President Abraham Lincoln credited them with helping to turn the tide of the war.

Cast

- Matthew Broderick as Colonel Robert Gould Shaw

- Denzel Washington as Private Silas Tripp

- Morgan Freeman as Sergeant Major John Rawlins

- Cary Elwes as Major Cabot Forbes

- Andre Braugher as Corporal Thomas Searles

- Jihmi Kennedy as Private Jupiter Sharts

- Cliff De Young as Colonel James Montgomery

- Alan North as Governor John Albion Andrew

- John Finn as Sergeant Major Mulcahy

- RonReaco Lee as Mute Drummer Boy

- Donovan Leitch as Captain Charles Fessenden Morse

- Bob Gunton as General Charles Garrison Harker

- Jay O. Sanders as General George Crockett Strong

- Raymond St. Jacques as Frederick Douglass

- Richard Riehle as Quartermaster

- JD Cullum as Henry Sturgis Russell

- Christian Baskous as Edward L. Pierce

- Peter Michael Goetz as Francis Shaw

- Jane Alexander as Sarah Blake Sturgis Shaw (uncredited)

Production

Kevin Jarre's inspiration for writing the film came from viewing the monument to Colonel Shaw and the 54th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry (the first formal unit of the U.S. Army to be made up entirely of African American men) in Boston Common.[3] His screenplay was based on Colonel Shaw's letters and on two books, Lincoln Kirstein's Lay This Laurel and Peter Burchard's One Gallant Rush.[4]

Principal filming took place primarily in Massachusetts and Georgia. Opening passages, meant to portray the Battle of Antietam, show volunteer military reenactors filmed at a major engagement at the Gettysburg battlefield. Zwick did not want to turn Glory "into a black story with a more commercially convenient white hero".[5] Actor Morgan Freeman noted: "We didn't want this film to fall under that shadow. This is a picture about the 54th Regiment, not Colonel Shaw, but at the same time the two are inseparable."[5] Zwick hired the writer Shelby Foote as a technical adviser; he later became widely known for his contributions to Ken Burns' popular PBS nine-episode documentary, The Civil War (1990).[5]

Glory was the first major motion picture to tell the story of African Americans fighting for their freedom in the Civil War. This came as a revelation to millions of Americans who had no knowledge of their participation.[who?] The 1965 movie Shenandoah, starring James Stewart, also depicted African Americans fighting for the Union, but suggested that the Federal army was integrated.

The movie is cited in the episode Def Poety's Society of the popular sitcom The Fresh Prince Of Bel-Air by the teacher and great friend of the protagonist of the series Mr. Fellows (played by actor Jonathan Emerson), pointing out that the great co-star of the film, Denzel Washington, was just great with his interpretation and that the South for him makes a very special reaction that only he can understand.

Soundtrack

| Untitled | |

|---|---|

The film's original motion picture soundtrack was released by the Virgin Records label on January 11, 1990. The score for the film was orchestrated by James Horner in association with the Boys Choir of Harlem.[6] Jim Henrikson edited the film's music, while Shawn Murphy mixed the score.[7]

Marketing

Monograph

A nonfiction study of the regiment first appeared in 1965 and was republished, in January 1990, in paperback by St. Martin's Press under the title One Gallant Rush: Robert Gould Shaw and His Brave Black Regiment. It dramatizes the events depicted in the film, expanding on how the 54th Massachusetts developed as battle-ready soldiers.[8] The book summarizes the historical events, and the aftermath of the first Union black regiment influencing the outcome of the war.[8]

Reception

Critical response

Vincent Canby, writing in The New York Times, said, "[Broderick] gives his most mature and controlled performance to date....[Washington is] an actor clearly on his way to a major screen career...The movie unfolds in a succession of often brilliantly realized vignettes tracing the 54th's organization, training and first experiences below the Mason-Dixon line. The characters' idiosyncrasies emerge."[4] Roger Ebert in the Chicago Sun-Times called it "a strong and valuable film no matter whose eyes it is seen through".[3] He believed the production design credited to Norman Garwood and the cinematography of Freddie Francis paid "enormous attention to period detail".[3]

| Glory is constructed as an inspirational tale, but the inspiration is not forced or false. It is rooted in the characters and the manner in which they overcome obstacles, including, most prominently, their own personal demons. |

| —James Berardinelli, writing for ReelViews[9] |

Similarly, Variety staff wrote that the film is "a stirring and long overdue tribute to the black soldiers who fought for the Union cause in the Civil War" and that it "has the sweep and magnificence of a Tolstoy battle tale or a John Ford saga of American history". On Broderick's performance, they felt his "boyishness becomes a key element of the drama, as the film shows him confiding his inadequacies".[10] Desson Howe of The Washington Post, pointed out some flaws including mentioning Broderick as "an amiable non-presence, creating unintentionally the notion that the 54th earned their stripes despite wimpy leadership".[11] The Chicago Reader's Jonathan Rosenbaum called Glory an "always interesting period film, well photographed by English cinematographer Freddie Francis".[12] The film, however, was not without its detractors. Peter Travers of Rolling Stone was not impressed at all with the overall acting, calling Broderick "catastrophically miscast as Shaw".[13] Alternatively, Richard Schickel of Time described the picture by saying, "the movie's often awesome imagery and a bravely soaring choral score by James Horner that transfigure the reality, granting it the status of necessary myth".[14]

Writing for Entertainment Weekly, Mark Bernardin said the film's strength "belongs to the powerhouse supporting cast – Morgan Freeman, Andre Braugher (in his first movie role), and Denzel Washington". He added: "The magic of Glory comes from the film itself. It speaks of heroism writ large, from people whom history had made small."[15] James Berardinelli writing for ReelViews, called the film "without question, one of the best movies ever made about the American Civil War," and noted that it "has important things to say, yet it does so without becoming pedantic".[9] Berardinelli also commented: "For a motion picture made on a relatively modest budget, Glory looks great. From a technical standpoint, the movie is a masterpiece, and the verisimilitude of the battle scenes is not in question."[9] Rating the film with four stars, critic Leonard Maltin wrote that it was "grand, moving, breathtakingly filmed (by veteran cinematographer Freddie Francis) and faultlessly performed". He called it "one of the finest historical dramas ever made".[16]

| Watching "Glory," I had one reccuring [sic] problem. I didn't understand why it had to be told so often from the point of view of the 54th's white commanding officer. Why did we see the black troops through his eyes — instead of seeing him through theirs? To put it another way, why does the top billing in this movie go to a white actor? |

| —Roger Ebert, writing in the Chicago Sun-Times[3] |

Chris Hicks of the Deseret News said the film is "big in scope, powerful in its storytelling drama, yet intimate in its character and relationship development." Referring to Broderick, he found he "does very well as the young officer, and among his troops are two of our finest actors — Morgan Freeman...and Denzel Washington".[17] The staff of TV Guide said of the film: "Richly plotted, alternately inspiring and horrifying, Glory is an enlightening and entertaining tribute to heroes too long forgotten." On the acting merits, they wrote, "Glory also contains especially compelling performances by Broderick, Washington, and Freeman."[18] Film critic Gene Siskel of the Chicago Tribune gave the film a thumbs up review, saying, "like Driving Miss Daisy, this is another admirable film that turns out to be surprisingly entertaining". He thought the film took on "some true social significance" and felt the actors portrayed the characters as "more than simply black men". He explained: "They're so different, that they become not merely standard Hollywood blacks, but true individuals."[19]

American Civil War historian James M. McPherson also lauded the film, saying that it "accomplished a remarkable feat in sensitizing a lot of today's black students to the role that their ancestors played in the Civil War in winning their own freedom".[20]

On Rotten Tomatoes, the film holds an approval rating of 93% based on 41 reviews, and an average rating of 7.9/10. The site's consensus reads: "Bolstered by exceptional cinematography, powerful storytelling, and an Oscar-winning performance by Denzel Washington, Glory remains one of the finest Civil War movies ever made."[21]

Accolades

The film was nominated and won several awards in 1989–90.[22][23] A complete list of awards the film won or was nominated for are listed below.

| Award | Category | Nominee | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| 62nd Academy Awards[24] | Best Actor in a Supporting Role | Denzel Washington | Won |

| Best Art Direction | Norman Garwood, Garrett Lewis | Nominated | |

| Best Cinematography | Freddie Francis | Won | |

| Best Film Editing | Steven Rosenblum | Nominated | |

| Best Sound | Donald O. Mitchell, Gregg Rudloff, Elliot Tyson, Russell Williams | Won | |

| 41st ACE Eddie Awards[25] | Best Edited Feature Film | ———— | Won |

| 44th British Academy Film Awards[26] | Best Cinematography | Freddie Francis | Nominated |

| British Society of Cinematographers Awards 1990[27] | Best Cinematography | Freddie Francis | Won |

| Casting Society of America Artios Awards 1990[28] | Best Casting for Feature Film, Drama | Mary Colquhoun | Nominated |

| 47th Golden Globe Awards[29] | Best Motion Picture – Drama | Freddie Fields | Nominated |

| Best Supporting Actor – Motion Picture | Denzel Washington | Won | |

| Best Director | Edward Zwick | Nominated | |

| Best Screenplay | Kevin Jarre | Nominated | |

| Best Original Score | James Horner | Nominated | |

| 33rd Grammy Awards[30] | Best Instrumental Composition Written for a Motion Picture or for Television | James Horner | Won |

| Kansas City Film Critics Circle Awards 1989[31] | Best Film | ———— | Won |

| Best Director | Edward Zwick | Won | |

| Best Supporting Actor | Denzel Washington | Won | |

| NAACP Image Awards 1992[32][33] | Outstanding Motion Picture | ———— | Won |

| Outstanding Supporting Actor in a Motion Picture | Denzel Washington | Won | |

| 1989 National Board of Review of Motion Pictures Awards[34] | Best Picture | ———— | Nominated |

| 1989 New York Film Critics Circle Awards[35] | Best Supporting Actor | Denzel Washington | Nominated |

| 1990 Political Film Society Awards[36] | Human Rights | ———— | Nominated |

| Writers Guild of America Awards 1989[37] | Best Adapted Screenplay | Kevin Jarre | Nominated |

American Film Institute Lists

- AFI's 100 Years...100 Movies - Nominated

- AFI's 100 Years...100 Thrills - Nominated

- AFI's 100 Years...100 Heroes and Villains:

- Trip - Nominated Hero

- AFI's 100 Years of Film Scores - Nominated

- AFI's 100 Years...100 Cheers - #31

- AFI's 100 Years...100 Movies (10th Anniversary Edition) - Nominated

Box office

The film premiered in cinemas on December 14, 1989, in limited release within the US. During its limited opening weekend, the film grossed $63,661 in business showing at 3 locations. Its official wide release began in theaters on February 16, 1990.[2] Opening in a distant 8th place, the film earned $2,683,350 showing at 801 cinemas. The film Driving Miss Daisy soundly beat its competition during that weekend opening in first place with $9,834,744.[38] The film's revenue dropped by 37% in its second week of release, earning $1,682,720. For that particular weekend, the film remained in 8th place screening in 809 theaters not challenging a top five position. The film Driving Miss Daisy, remained in first place grossing $6,107,836 in box office revenue.[39] The film went on to top out domestically at $26,828,365 in total ticket sales through a 17-week theatrical run.[2] For 1989 as a whole, the film would cumulatively rank at a box office performance position of 45.[40]

Home media

Following its release in theaters, the film was released on VHS video format on June 22, 1990.[41] The Region 1 DVD widescreen edition of the film was released in the US on January 20, 1998. Special DVD features include: interactive menus, scene selections, widescreen 1.85:1 color anamorphic format, along with subtitles in English, Italian, Spanish and French.[42]

A special repackaged version of Glory was also officially released on DVD on January 2, 2007. It includes two discs featuring: widescreen and full screen versions of the film; Picture-in-Picture video commentary by director Ed Zwick and actors Morgan Freeman and Matthew Broderick; a director's audio commentary; and a documentary entitled, The True Story of Glory Continues narrated by Morgan Freeman. Also included are: an exclusive featurette entitled, Voices of Glory, an original featurette, deleted scenes, production notes, theatrical trailers, talent files, and scene selections.[43]

The Blu-ray disc version of the film was released on June 2, 2009. Special features include: a virtual civil war battlefield, interactive map, The Voice Of Glory feature, The True Story Continues documentary, the making of Glory, director's commentary, and deleted scenes.[44] The film is displayed in widescreen 1.85:1 color format in 1080p screen resolution. The audio is enhanced with Dolby TrueHD sound and is available with subtitles in English, Spanish, French, and Portuguese.[44] A UMD version of the film for the Sony PlayStation Portable was also released on July 1, 2008. It features dubbed, subtitled, and color widescreen format viewing options.[45]

See also

References

- ^ "Glory". The Numbers. Retrieved November 7, 2010.

- ^ a b c "Glory". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved November 7, 2010.

- ^ a b c d Ebert, Roger (January 12, 1990). Glory.Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved 2010-11-07.

- ^ a b Canby, Vincent (December 14, 1989). Glory (1989). The New York Times. Retrieved 2010-11-07.

- ^ a b c "Glory (1989)". Turner Classic Movies. Retrieved November 7, 2010.

- ^ Glory Original Motion Picture Soundtrack. Barnes & Noble. Retrieved 2010-11-07.

- ^ "Glory (1989) Cast and Credits". Yahoo! Movies. Retrieved November 7, 2010.

- ^ a b Burchard, Peter (1990). One Gallant Rush: Robert Gould Shaw and His Brave Black Regiment. St. Martin's Press. ISBN 978-0-312-04643-9.

- ^ a b c Berardinelli, James (December 1989). Glory. ReelViews. Retrieved 2010-11-07.

- ^ Glory. Variety (December 31, 1988).

- ^ Desson, Howe (January 12, 1990). 'Glory' (R). The Washington Post. Retrieved 2010-11-07.

- ^ Rosenbaum, Jonathan (December 1989). Glory. Chicago Reader. Retrieved 2010-11-07.

- ^ Travers, Peter (December 1989). Glory (1989). Rolling Stone. Retrieved 2010-11-07.

- ^ Schickel, Richard (December 5, 1989). Cinema: Of Time and the River. TIME. Retrieved 2010-11-07.

- ^ Bernardin, Mark (February 13, 2001). Glory: Special Edition (2001). Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved 2010-11-07.

- ^ Maltin, Leonard (August 5, 2008). Leonard Maltin's 2009 Movie Guide. Signet. p. 528. ISBN 978-0-452-28978-9.

- ^ Hicks, Chris (February 20, 1990). Glory. Deseret News. Retrieved 2010-11-07.

- ^ Glory: Review. TV Guide (December 1989).

- ^ Siskel, Gene (December 1989). Glory[permanent dead link]. At the Movies. Retrieved 2010-11-07.

- ^ McPherson, James M.; Lamb, Brian (May 22, 1994). "James McPherson: What They Fought For, 1861-1865". Booknotes. National Cable Satellite Corporation. Archived from the original on March 9, 2016. Retrieved March 9, 2016.

Glory accomplished a remarkable feat in sensitizing a lot of today's black students to the role that their ancestors played in the Civil War in winning their own freedom.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ http://www.rottentomatoes.com/m/1008415-glory/

- ^ "Glory: Awards & Nominations". MSN Movies. Retrieved November 7, 2010.

- ^ "Glory (1989) Awards & Nominations". Yahoo! Movies. Archived from the original on February 16, 2008. Retrieved November 7, 2010.

- ^ "Nominees & Winners for the 62nd Academy Awards". Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. March 26, 1990. Archived from the original on February 21, 2014. Retrieved January 24, 2016.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Nominees & Recipients". American Cinema Editors. Archived from the original on February 24, 2011. Retrieved November 7, 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Film Nominations 1990". British Academy of Film and Television Arts. Archived from the original on December 26, 2007. Retrieved January 24, 2016.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Best Cinematography Award". The British Society of Cinematographers. Archived from the original on April 14, 2009. Retrieved November 7, 2010.

- ^ "Artios Award Winners". CastingSociety.com. Retrieved November 7, 2010.

- ^ "Glory". GoldenGlobes.org. Archived from the original on September 29, 2006. Retrieved November 7, 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Videos for 33rd Annual Grammy Awards". Grammy.com. Retrieved November 7, 2010.

- ^ "KCFCC Award Winners 1980-1989". kcfcc.org. Archived from the original on April 10, 2009. Retrieved November 7, 2010.

- ^ "Image Awards History". NAACP Image Awards. Archived from the original on March 30, 2006. Retrieved November 7, 2010.

- ^ "Naacp's Image Awards Honor Black Entertainers". Orlando Sentinel. Retrieved November 7, 2010.

- ^ "Awards for 1989". National Board of Review. Archived from the original on November 25, 2010. Retrieved November 7, 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "1989 Awards". New York Film Critics Circle. Archived from the original on November 9, 2006. Retrieved November 7, 2010.

- ^ "Previous Winners". Political Film Society. Archived from the original on October 28, 2009. Retrieved November 7, 2010.

- ^ "Awards Winners". Writers Guild Awards. Archived from the original on October 1, 2006. Retrieved November 7, 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "February 16–19, 1990 Weekend". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved November 7, 2010.

- ^ "October 23–25, 1990 Weekend". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved November 7, 2010.

- ^ "1989 Domestic Grosses". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved November 7, 2010.

- ^ Glory VHS Format. Amazon.com. ASIN 6301777867.

- ^ "Glory DVD". DVDEmpire.com. Retrieved November 7, 2010.

- ^ "Glory Special Edition". Amazon.com. Retrieved November 7, 2010.

- ^ a b "Glory Blu-ray". DVDEmpire.com. Retrieved November 7, 2010.

- ^ "Glory UMD for PSP". Amazon.com. Retrieved November 7, 2010.

External links

- Official website

- Glory at AllMovie

- Glory at IMDb

- Glory at the TCM Movie Database

- Glory at the Movie Review Query Engine

- Glory at Rotten Tomatoes

- Glory at Box Office Mojo

- video taken from the Fresh Prince of Bel-Air for the citation of the movie: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LB7R-JOIFLI

- 1989 films

- 1980s drama films

- 1980s war films

- American films

- American Civil War films

- American war drama films

- English-language films

- African Americans in the Civil War

- Films about American slavery

- Films about race and ethnicity

- Massachusetts in the American Civil War

- War films based on actual events

- TriStar Pictures films

- Films featuring a Best Supporting Actor Academy Award-winning performance

- Films featuring a Best Supporting Actor Golden Globe winning performance

- Films that won the Best Sound Mixing Academy Award

- Films whose cinematographer won the Best Cinematography Academy Award

- Films scored by James Horner

- Films directed by Edward Zwick

- Films set in Georgia (U.S. state)

- Films set in Massachusetts

- Films set in South Carolina