Jötunn

This article may need to be rewritten to comply with Wikipedia's quality standards. (December 2011) |

This article needs additional citations for verification. (September 2008) |

A jötunn (anglicized jotunn or jotun; /[invalid input: 'icon']ˈjoʊtən/, /ˈjoʊtʊn/, or /ˈjɔːtʊn/; Icelandic: [ˈjœːtʏn]; from Old Norse jǫtunn /ˈjɔtunː/; often glossed as giant or ettin) is a being seen throughout Norse mythology. The Jötunn are a mythological race, separate from the Æsir and Vanir but of comparable strength and ability. As seen through a great number of texts and poems the Jötunn are often in opposition or competition to the Æsir or Vanir. A number of Jötunn intermarry with the Æsir and Vanir or interact with them in a non-hostile manner. Their otherworldly homeland is Jötunheimr, one of the nine worlds of Norse cosmology, separated from Midgard, the world of humans, by high mountains or dense forests. Other place names are also associated with them, including Niflheimr (land of ice, mist and fog occupied by Hrimthurs or Frost Giants), Utgarðr (Jötnar stronghold within the giants' realm) and Járnviðr (A heavily wooded area inhabited by troll-women who bear giants).

Etymology

In Old Norse, the beings were called jǫtnar (singular jǫtunn, the regular reflex of the stem jǫtun- and the nominative singular ending -r), or risar (singular risi), in particular bergrisar ('mountain-risar'), or þursar (singular þurs), in particular hrímþursar ('rime-thurs'). Giantesses could also be known as gýgjar (singular gýgr) or íviðjur (singular íviðja).

Jǫtunn (Proto-Germanic *etunaz) might have the same root as "eat" (Proto-Germanic *etan) and accordingly had the original meaning of "glutton" or "man-eater", possibly in the sense of personifying chaos, the destructive forces of nature. Following the same logic, þurs might be derivative of "thirst" or "blood-thirst." Risi is probably akin to "rise," and so means "towering person" (akin to German Riese, Dutch reus, archaic Swedish rese, giant). The word "jotun" survives in modern Norwegian as giant (though more commonly called trolls), and has evolved into jætte and jätte in modern Swedish and Danish, while in Faroese they are called jatnir [jaʰtnɪɹ]/[jaʰknɪɹ] (Singular: jøtun [jøːtʊn]). In modern Icelandic jötunn has kept its original meaning. In Old English, the cognate to jötunn is eoten, whence modern English ettin.

The Elder Futhark rune ᚦ, called Thurs (from Proto-Germanic *Þurisaz), later evolved into the letter Þ. In Scandinavian folklore, the Norwegian name tusse for a kind of troll or nisse, derives from Old Norse Þurs. Old English also has the cognate þyrs of the same meaning.

Norse jötnar

Origins

The first living being formed in the primeval chaos known as Ginnungagap was a giant of monumental size, called Ymir. When the icy mists of Niflheimr met with the heat of Múspellsheimr Ymir was born out of the joining of these two extreme forces from either world in the great void. Contained within Snorri Sturluson's Gylfaginning, Ymir's creation is recounted:

- "Just as cold arose out of Niflheim, and all terrible things, so also all that looked toward Múspellheim became hot and glowing; but Ginnungagap was as mild as windless air, and when the breath of heat met the rime, so that it melted and dripped, life was quickened from the yeast-drops, by the power of that which sent the heat, and became a man's form. And that man is named Ymir..."(source)

When he slept a jötunn son and a jötunn daughter grew from his armpits, and his two feet procreated and gave birth to a son, a monster with six heads. These three beings gave rise to the race of hrímþursar (rime thurs, frost giants), who populated Niflheim. The gods instead claim their origin from a certain Búri. When the giant Ymir subsequently was slain by Odin, Vili and Vé (the grandsons of Búri), his blood (i.e. water) deluged Niflheim and killed all of the jötnar, apart from one known as Bergelmir and his spouse, who then repopulated their kind. It is mentioned in Vafþrúðnismál that the Earth was born of Ymirs flesh, the mountains of his bones, the sky out of the "frost-cold giant's skull", and the ocean out of his blood.

Character of the jötnar

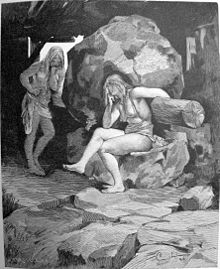

Some of the jötnar are attributed with hideous appearances – claws, fangs, and deformed features, apart from a generally hideous size. Some of them may even have many heads, such as Thrivaldi who had nine of them, or an overall non-humanoid shape; so were Jörmungandr and Fenrir, two of the children of Loki.

Yet when jötnar are named and more closely described, they are often given the opposite characteristics. Many of the jötnar are described as beautiful, Skaði being described as "the shining bride of the gods". Although some jötnar are said to have been of considerable size, many were of no difference in size then that of the Æsir or Vanir. The Jötunn do appear to have some shared characteristics between a few of them, "according to well established skaldic precedents, any figure that lives on, in or among rocks may be assumed to be a giant". This is most likely due to their association with the creation of the earth. The Jötunn are an ancient race, being the first beings created, they carry wisdom from bygone times. It is the jötnar Mímir and Vafþrúðnir Odin seeks out to gain ancient knowledge about Fimbulvinter, the great winter that marks the start of the end of times, Ragnarök. In Vafþrúðnismál Odin was wary to visit the giant's hall, as he was described by Frigg as being the most powerful giant she knows. This is a clear testament to the comparable levels of ability between this ancient race and the gods. It is often referenced in skaldic texts that the giants married or formed relationships with many of the Æsir and Vanir. In Snorri Sturluson's Haustlöng (source) Njörðr is married to the giantess Skaði as part of the compensation provided to her by the Æsir for killing her father, Þjazi. In Skírnismál (also referred to as För Skírnis) Gerðr becomes the consort of Freyr after he becomes enamored with her.

- "Freyr had seated himself...and looked into all the worlds. He looked into Giantland (Jötunheimr) and saw there a beautiful girl (Gerðr)... from that he caught a great sickness of heart"

Her relationship with Freyr is noticeable in the fact that it is not consensual. Freyr's page, Skírnir, frist attempted to bribe Gerðr then subsequently had to threaten Gerðr with banishment and a life devoid of pleasure in order to convince her to lie with Freyr. This shows that the Jötunn were not always acting as the agressor in Norse mythology, but sometimes quite the opposite. Odin gains the love of Gunnlod, and even Thor, the great slayer of their kind, produces a child with Járnsaxa; Magni. As such, they appear as minor gods themselves, which can also be said about the sea giant Ægir, far more connected to the gods than to the other jötnar.

Ragnarök and the fire jötnar

A certain class of jötnar are the fire jötnar (Múspellsmegir, "sons of Muspell", or eldjötnar), said to reside in Muspelheim, the world of heat and fire, ruled by the fire jötunn Surtr ("the black one"). The main role of the fire jötnar in Norse mythology is to wreak the final destruction of the world by setting fire to the world at the end of Ragnarök, when the jötnar of Jotunheim and the forces of Hel shall launch an attack on the gods, and kill all but a few of them.

See also

Notes

References

- Abram, Christopher. Myths of the Pagan North: The Gods of the Norsemen. London: Continuum, 2011.

- Christiansen, Eric. The Norsemen in the Viking Age. Oxford, UK: Blackwell, 2002.

- Faulkes, Anthony (transl. and ed.) (1987). Edda (Snorri Sturluson). Everyman. ISBN 0-460-87616-3

- Larrington, Carolyne (transl. and ed.) (1996). The Poetic Edda. Oxford World's Classics. ISBN 0-19-283946-2

- Lindow, John. Handbook of Norse Mythology. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, 2001.

- Machan, Tim William. Vafþrúđnismál. Durham: [School of English, Univ.], 1988.

- Þjóðólfr, ór Hvini, and Richard North. The Haustlǫng of Þjóðólfr of Hvinir. Middlesex, UK: Hisarlik, 1997

- Reichardt, Konstantin. Hymiskviða: Interpretation, Wortschatz, Alter. Halle (Saale): Max Niemeyer Verlag, 1933

- Snorri, Sturluson, and Gottfried Lorenz. Gylfaginning. Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, 1984

This article contains content from the Owl Edition of Nordisk familjebok, a Swedish encyclopedia published between 1904 and 1926, now in the public domain.

This article contains content from the Owl Edition of Nordisk familjebok, a Swedish encyclopedia published between 1904 and 1926, now in the public domain.