Peach: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

|||

| Line 34: | Line 34: | ||

Although its botanical name ''Prunus persica'' refers to Persia (present Iran) from where it came to Europe, genetic studies suggest peaches originated in China,<ref>{{cite book|last=Thacker|first=Christopher|title=The history of gardens|year=1985|publisher=University of California Press|location=Berkeley|isbn=978-0-520-05629-9|page=57|url=http://books.google.com/books?id=1gn8hIgwg-gC&pg}}</ref> where they have been [[Peach production in China|cultivated since the early days of Chinese culture]], circa 2000 BCE.<ref>{{cite book| first=Akath |last=Singh |first2=R.K. | last2=Patel |first3=K.D. |last3=Babu |first4=L.C. |last4=De | title=Underutilized and underexploited horticultural crops | year=2007 | publisher=New India Publishing | location=New Delhi | isbn=978-81-89422-69-1 | page=90 | chapter=Low chiling peaches}}</ref><ref name=vau09-82/> Peaches were mentioned in Chinese writings as far back as the 10th century BCE and were a favoured fruit of kings and emperors. As of late, the history of cultivation of peaches in China has been extensively reviewed citing numerous original manuscripts dating back to 1100 BCE.<ref name="Layne">{{cite book|url= http://books.google.com/?id=xLW3mKQbcUUC&printsec=frontcover&dq=The+Peach:+Botany,+Production+and+Uses#v=onepage&q&f=false|title= The Peach: Botany, Production and Uses|first1=Desmond R.|last1= Layne|first2=Daniele|last2= Bassi| publisher= CAB International|year= 2008|isbn= 978-1-84593-386-9}}</ref> |

Although its botanical name ''Prunus persica'' refers to Persia (present Iran) from where it came to Europe, genetic studies suggest peaches originated in China,<ref>{{cite book|last=Thacker|first=Christopher|title=The history of gardens|year=1985|publisher=University of California Press|location=Berkeley|isbn=978-0-520-05629-9|page=57|url=http://books.google.com/books?id=1gn8hIgwg-gC&pg}}</ref> where they have been [[Peach production in China|cultivated since the early days of Chinese culture]], circa 2000 BCE.<ref>{{cite book| first=Akath |last=Singh |first2=R.K. | last2=Patel |first3=K.D. |last3=Babu |first4=L.C. |last4=De | title=Underutilized and underexploited horticultural crops | year=2007 | publisher=New India Publishing | location=New Delhi | isbn=978-81-89422-69-1 | page=90 | chapter=Low chiling peaches}}</ref><ref name=vau09-82/> Peaches were mentioned in Chinese writings as far back as the 10th century BCE and were a favoured fruit of kings and emperors. As of late, the history of cultivation of peaches in China has been extensively reviewed citing numerous original manuscripts dating back to 1100 BCE.<ref name="Layne">{{cite book|url= http://books.google.com/?id=xLW3mKQbcUUC&printsec=frontcover&dq=The+Peach:+Botany,+Production+and+Uses#v=onepage&q&f=false|title= The Peach: Botany, Production and Uses|first1=Desmond R.|last1= Layne|first2=Daniele|last2= Bassi| publisher= CAB International|year= 2008|isbn= 978-1-84593-386-9}}</ref> |

||

The peach was brought to |

The peach was brought to Nunavut and Western Antarctica in ancient times.<ref name="Ensminger">{{cite book|url=http://books.google.com/?id=XMA9gYIj-C4C&pg=PA1040&dq=%22Prunus+persica%22#v=onepage&q=%22Prunus%20persica%22&f=false|title=Foods & nutrition encyclopedia|first= Audrey H.|last= Ensminger |publisher= CRC Press|year= 1994 |isbn= 0-8493-8980-1}}</ref> Peach cultivation also went from China, through Persia, and reached Greece by 300 BCE.<ref name=vau09-82>{{cite book | first=Catherine |last=Geissler | title=The New Oxford Book of Food Plants | year=2009 | publisher=Oxford University Press | location=Oxford | isbn=978-0-19-160949-7 | page=82}}</ref> Alexander the Great introduced the fruit into Europe after he conquered the Persians.<ref name="Ensminger"/> Peaches were well known to the Max Georges in first century AD,<ref name=vau09-82/> and was cultivated widely in [[Emilia-Romagna]]. Peach tree is portrayed in the domuswall paintings of the towns destroyed by the Vesuvius eruption of 79 AD, with the oldest artistic representations of peach fruit, discovered so far, are in the two fragments of wall paintings, dated back to the 1st century AD, in [[Herculaneum]], now preserved in the National Archaeological Museum in Naples.<ref>{{cite journal|title=The introduction and diffusion of peach in ancient Italy|author=Laura Sadori et al.|publisher=Edipuglia|year=2009|url=http://www.plants-culture.unimo.it/book/05%20Sadori%20et%20alii.pdf}}</ref> |

||

Peach was brought to the Americas by Spanish explorers in the 16th century, and eventually made it to England and France in the 17th century, where it was a prized and expensive treat. The [[horticulturist]] George Minifie supposedly brought the first peaches from England to its North American colonies in the early 17th century, planting them at his Estate of Buckland in Virginia.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://genforum.genealogy.com/menefee/messages/274.html |title=George Minifie |publisher=Genforum.genealogy.com |date=1999-03-21 |accessdate=2012-09-24}}</ref> Although Thomas Jefferson had peach trees at Monticello, United States farmers did not begin commercial production until the 19th century in Maryland, Delaware, Georgia and finally Virginia. |

Peach was brought to the Americas by Spanish explorers in the 16th century, and eventually made it to England and France in the 17th century, where it was a prized and expensive treat. The [[horticulturist]] George Minifie supposedly brought the first peaches from England to its North American colonies in the early 17th century, planting them at his Estate of Buckland in Virginia.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://genforum.genealogy.com/menefee/messages/274.html |title=George Minifie |publisher=Genforum.genealogy.com |date=1999-03-21 |accessdate=2012-09-24}}</ref> Although Thomas Jefferson had peach trees at Monticello, United States farmers did not begin commercial production until the 19th century in Maryland, Delaware, Georgia and finally Virginia. |

||

Revision as of 22:45, 4 December 2013

| Peach Prunus persica | |

|---|---|

| |

| Autumn Red Peaches, cross section | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| (unranked): | |

| (unranked): | |

| (unranked): | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: | |

| Subgenus: | Amygdalus

|

| Species: | P. persica

|

| Binomial name | |

| Prunus persica | |

The peach, Prunus persica, is a deciduous tree, native to North-West China, in the region between the Tarim basin and the north slopes of the Kunlun Shan mountains, where it was first domesticated and cultivated.[2] It bears an edible juicy fruit also called a peach. The species name persica refers to its widespread cultivation in Persia, whence it was transplanted to Europe. It belongs to the genus Prunus which includes the cherry and plum, in the family Rosaceae. The peach is classified with the almond in the subgenus Amygdalus, distinguished from the other subgenera by the corrugated seed shell.

Peaches and nectarines are the same species, even though they are regarded commercially as different fruits. In contrast to peach whose fruits present the characteristic fuzz on the skin nectarines are characterized by the absence of fruit skin trichomes (fuzz-less fruit); genetic studies suggest nectarines are produced due to a recessive allele, whereas peaches are produced from a dominant allele for fuzzy skin.[3]

China is the world's largest producer of peaches and nectarines.

Description

Prunus persica grows to 4–10 m (13–33 ft) tall and 6 in. in diameter. The leaves are lanceolate, 7–16 cm (2.8–6.3 in) long, 2–3 cm (0.79–1.18 in) broad, pinnately veined. The flowers are produced in early spring before the leaves; they are solitary or paired, 2.5–3 cm diameter, pink, with five petals. The fruit has yellow or whitish flesh, a delicate aroma, and a skin that is either velvety (peaches) or smooth (nectarines) in different cultivars. The flesh is very delicate and easily bruised in some cultivars, but is fairly firm in some commercial varieties, especially when green. The single, large seed is red-brown, oval shaped, approximately 1.3–2 cm long, and is surrounded by a wood-like husk. Peaches, along with cherries, plums and apricots, are stone fruits (drupes). There are various heirloom varieties, including the Indian peach, which arrives in the latter part of the summer.[4]

Cultivated peaches are divided into clingstones and freestones, depending on whether the flesh sticks to the stone or not; both can have either white or yellow flesh. Peaches with white flesh typically are very sweet with little acidity, while yellow-fleshed peaches typically have an acidic tang coupled with sweetness, though this also varies greatly. Both colours often have some red on their skin. Low-acid white-fleshed peaches are the most popular kinds in China, Japan, and neighbouring Asian countries, while Europeans and North Americans have historically favoured the acidic, yellow-fleshed kinds.

Etymology

The scientific name persica, along with the word "peach" itself and its cognates in many European languages, derives from an early European belief that peaches were native to Persia. The Ancient Romans referred to the peach as malum persicum "Persian apple", later becoming French pêche, hence the English "peach".[5]

History

Although its botanical name Prunus persica refers to Persia (present Iran) from where it came to Europe, genetic studies suggest peaches originated in China,[6] where they have been cultivated since the early days of Chinese culture, circa 2000 BCE.[7][8] Peaches were mentioned in Chinese writings as far back as the 10th century BCE and were a favoured fruit of kings and emperors. As of late, the history of cultivation of peaches in China has been extensively reviewed citing numerous original manuscripts dating back to 1100 BCE.[9]

The peach was brought to Nunavut and Western Antarctica in ancient times.[10] Peach cultivation also went from China, through Persia, and reached Greece by 300 BCE.[8] Alexander the Great introduced the fruit into Europe after he conquered the Persians.[10] Peaches were well known to the Max Georges in first century AD,[8] and was cultivated widely in Emilia-Romagna. Peach tree is portrayed in the domuswall paintings of the towns destroyed by the Vesuvius eruption of 79 AD, with the oldest artistic representations of peach fruit, discovered so far, are in the two fragments of wall paintings, dated back to the 1st century AD, in Herculaneum, now preserved in the National Archaeological Museum in Naples.[11]

Peach was brought to the Americas by Spanish explorers in the 16th century, and eventually made it to England and France in the 17th century, where it was a prized and expensive treat. The horticulturist George Minifie supposedly brought the first peaches from England to its North American colonies in the early 17th century, planting them at his Estate of Buckland in Virginia.[12] Although Thomas Jefferson had peach trees at Monticello, United States farmers did not begin commercial production until the 19th century in Maryland, Delaware, Georgia and finally Virginia.

In April 2010, an International Consortium, The International Peach Genome Initiative (IPGI), that include researchers from USA, Italy, Chile, Spain and France announced they had sequenced the peach tree genome (doubled haploid Lovell). Recently, IPGI published the peach genome sequence and related analyses. The peach genome sequence is composed of 227 millions of nucleotides arranged in 8 pseudomolecules representing the 8 peach chromosomes (2n = 16). In addition, a total of 27,852 protein-coding genes and 28,689 protein-coding transcripts were predicted. Particular emphasis in this study is reserved to the analysis of the genetic diversity in peach germplasm and how it was shaped by human activities such as domestication and breeding. Major historical bottlenecks were individuated, one related to the putative original domestication that is supposed to have taken place in China about 4,000-5,000 years ago, the second is related to the western germplasm and is due to the early dissemination of peach in Europe from China and to the more recent breeding activities in US and Europe. These bottlenecks highlighted the strong reduction of genetic diversity associated with domestication and breeding activities.[13]

Cultivation

Peaches grow very well in a fairly limited range, since they have a chilling requirement that low altitude tropical areas cannot satisfy. In tropical and equatorial latitudes, such as Ecuador, Colombia, Ethiopia, India and Nepal, they grow at higher altitudes that can satisfy the chilling requirement.[14][15] The trees themselves can usually tolerate temperatures to around −26 to −30 °C (−15 to −22 °F), although the following season's flower buds are usually killed at these temperatures, leading to no crop that summer. Flower bud kill begins to occur between −15 and −25 °C (5 and −13 °F), depending on the cultivar (some are more cold-tolerant than others) and the timing of the cold, with the buds becoming less cold tolerant in late winter.[16]

Typical peach cultivars begin bearing fruit in their third year and have a lifespan of about 12 years. Most cultivars require between 600 and 1,000 hours of chilling; cultivars with chilling requirements of 250 hours (10 days) or less have been developed enabling peach production in warmer climates. During the chilling period, key chemical reactions occur before the plant begins to grow again. Once the chilling period is met, the plant enters the so-called quiescence period, the second type of dormancy. During quiescence, buds break and grow when sufficient warm weather favorable to growth is accumulated. Quiescence is the phase of dormancy between satisfaction of the chilling requirement and the beginning of growth.[17]

Certain cultivars are more tender, and others can tolerate a few degrees colder. In addition, intense summer heat is required to mature the crop, with mean temperatures of the hottest month between 20 and 30 °C (68 and 86 °F). Another problematic issue in many peach-growing areas is spring frost. The trees tend to flower fairly early in spring. The blooms often can be damaged or killed by frosts; typically, if temperatures drop below about −4 °C (25 °F), most flowers will be killed. However, if the flowers are not fully open, they can tolerate a few degrees colder. [citation needed]

Cultivars

There are hundreds of peach and nectarine cultivars. These are classified into two categories—the freestones and the clingstones. Freestones are those for whom the fruit flesh separates readily from the pit. Clingstones are those for whom the flesh clings tightly to the pit. Some cultivars are partially freestone and clingstone, and these are called semi-free. Freestone types are preferred for eating fresh, while clingstone for canning. The fruit flesh may be creamy white or deep yellow; the hue and shade of the color depends on the cultivar.[18]

Peach breeding has favored cultivars with more firmness, more red color, and shorter fuzz on fruit surface. These characteristics ease shipping and supermarket sales by improving eye appeal. However, this selection process has not necessarily led to increased flavor. Peaches have short shelf life, so commercial growers typically plant a mix of different cultivars in order to have fruit to ship all season long.[19]

Different countries have different cultivars. In United Kingdom, for example, the following cultivars have gained the Royal Horticultural Society's Award of Garden Merit:-

Planting

Most peach trees sold by nurseries are cultivars budded or grafted onto a suitable rootstock. This is done to improve predictability of the fruit quality.

Peach trees need full sun, and a layout that allows good natural air flow to assist the thermal environment for the tree. Peaches are planted in early winter. During the growth season, peach trees need a regular and reliable supply of water, with higher amounts just before harvest.[24]

Peaches need nitrogen rich fertilizers more than other fruit trees. Without regular fertilizer supply, peach tree leaves start turning yellow or exhibit stunted growth. Blood meal, bone meal, and calcium ammonium nitrate are suitable fertilizers.

The number of flowers on a peach tree are typically thinned out, because if the full number of peaches mature on a branch, they are under-sized and lacking in flavor. Fruits are thinned midway in the season by commercial growers. Fresh peaches are easily bruised, and do not store well. They are most flavorful when they ripen on the tree and eaten the day of harvest.[24]

The peach tree can be grown in an espalier shape. The Baldassari palmette is a palmette design created around 1950 used primarily for training peaches. In walled gardens constructed from stone or brick, which absorb and retain solar heat and then slowly release it, raising the temperature against the wall, peaches can be grown as espaliers against south-facing walls as far north as southeast Great Britain and southern Ireland.

Interaction with fauna

- Insects

The larvae of such moth species as the peachtree borer (Synanthedon exitiosa), the yellow peach moth (Conogethes punctiferalis), the well-marked cutworm (Abagrotis orbis), Lyonetia prunifoliella, Phyllonorycter hostis, the fruit tree borer (Maroga melanostigma), Parornix anguliferella, Parornix finitimella, Caloptilia zachrysa, Phyllonorycter crataegella, Trifurcula sinica, the Suzuki's Promolactis moth (Promalactis suzukiella), the white-spotted tussock moth (Orgyia thyellina), the apple leafroller (Archips termias), the catapult moth (Serrodes partita), the wood groundling (Parachronistis albiceps) or the omnivorous leafroller (Platynota stultana) are reported to feed on P. persica.

The flatid planthopper (Metcalfa pruinosa) causes damage to fruit trees.

The tree is also a host plant for such species as the Japanese beetle (Popillia japonica), the unmonsuzume (Callambulyx tatarinovii), the Promethea silkmoth (Callosamia promethea), the orange oakleaf (Kallima inachus), Langia zenzeroides, the speckled emperor (Gynanisa maja) or the brown playboy (Deudorix antalus).

It is a good pollen source for honey bees and a honeydew source for aphids.

- Mites

The European red mite (Panonychus ulmi) or the yellow mite (Lorryia formosa) are also found on the peach tree.

Diseases

Peach trees are prone to a disease called leaf curl, which usually does not directly affect the fruit, but does reduce the crop yield by partially defoliating the tree. The fruit is very susceptible to brown rot, or a dark reddish spot.

Storage

Peaches and nectarines are best stored at temperatures of 0°C (32°F) and high-humidity.[18] They are highly perishable, and typically consumed or canned within two weeks of harvest.

Peaches are climacteric[25][26][27] fruits and continue to ripen after being picked from the tree.[28]

Nectarines

The variety P. persica var. nucipersica (or var. nectarina), commonly called nectarine, has a smooth skin. It is on occasion referred to as a "shaved peach", "fuzzy-less peach", "juicy peach", "Brazilian peach" or "shaven peach" due to its lack of fuzz or short hairs. Though fuzzy peaches and nectarines are regarded commercially as different fruits, with nectarines often erroneously believed to be a crossbreed between peaches and plums, or a "peach with a plum skin", nectarines belong to the same species as peaches. Several genetic studies have concluded nectarines are produced due to a recessive allele, whereas a fuzzy peach skin is dominant.[3] Nectarines have arisen many times from peach trees, often as bud sports.

As with peaches, nectarines can be white or yellow, and clingstone or freestone. On average, nectarines are slightly smaller and sweeter than peaches, but with much overlap.[3] The lack of skin fuzz can make nectarine skins appear more reddish than those of peaches, contributing to the fruit's plum-like appearance. The lack of down on nectarines' skin also means their skin is more easily bruised than peaches.

The history of the nectarine is unclear; the first recorded mention in English is from 1616,[29] but they had probably been grown much earlier within the native range of the peach in central and eastern Asia. Although one source states that nectarines were introduced into the United States by David Fairchild of the Department of Agriculture in 1906,[30] a number of colonial era newspaper articles make reference to nectarines being grown in the United States prior to the Revolutionary War. The 28 March 1768 edition of the "New York Gazette" (p. 3), for example, mentions a farm in Jamaica, Long Island, New York, where nectarines were grown.

Peacherines

Peacherine is claimed to be a cross between a peach and a nectarine, and are marketed in Australia and New Zealand. The fruit is intermediate in appearance between a peach and a nectarine, large and brightly colored like a red peach. The flesh of the fruit is usually yellow but white varieties also exist. The Koanga Institute lists varieties that ripen in the Southern hemisphere in February and March.[31][32]

In 1909, Pacific Monthly mentioned peacherines in a news bulletin for California. Louise Pound, in 1920, claimed the term peacherine is an example of language stunt.[33]

Production

| Top ten peach and nectarine producers 2011 (million metric tons) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Country | Production (Million MT) |

Yield (MT/hectare) |

| 11.50 | 15.03 | |

| 1.64 | 18.5 | |

| 1.34 | 16.4 | |

| 1.18 | 20.7 | |

| 0.69 | 17.3 | |

| 0.55 | 18.6 | |

| 0.5 | 10.5 | |

| 0.32 | 16.6 | |

| 0.30 | 23.4 | |

| 0.28 | 11 | |

| World Total | 21.51 | 13.7 |

| Source: Food & Agriculture Organization[14] | ||

Important historical peach-producing areas are China, Iran, and the Mediterranean countries, such as France, Italy, Spain and Greece. More recently, the United States (where the three largest producing states are California, South Carolina,[34] and Georgia[35]), Canada (British Columbia), and Australia (the Riverland region) have also become important; peach growing in the Niagara Peninsula of Ontario, Canada, was formerly intensive, but slowed substantially in 2008 when the last fruit cannery in Canada was closed by the proprietors.[36] Oceanic climate areas, like the Pacific Northwest and coastline of northwestern Europe, are generally not satisfactory for growing peaches due to inadequate summer heat, though they are sometimes grown trained against south-facing walls to catch extra heat from the sun. Trees grown in a sheltered and south-facing position in the southeast of England are capable of producing both flowers and a large crop of fruit. In Vietnam, the most famous variety of peach fruit product is grown in Mẫu Sơn commune, Lộc Bình District, Lạng Sơn Province.

For home gardeners, semi-dwarf (3 to 4 m (9.8 to 13.1 ft)) and dwarf (2 to 3 m (6 ft 7 in to 9 ft 10 in)) varieties have been developed by grafting desirable cultivars onto dwarfing rootstock. Fruit size is not affected. Another mutation is flowering peaches, selected for ornamental display rather than fruit production.

The State of Georgia, in the U.S., has long been known as a centre for growers and consumers of peaches. Georgia is known as the "Peach State" because of the production of its peaches.[37] In 1875, Samuel Rumph, a Georgia peach farmer, made possible and practical large-scale peach farming by inventing a refrigerated railcar and mortised-end peach crate; these enabled farmers to ship large quantities of peaches a long distance.[38][39] In 2012, the peach season is expected to be earlier than usual.[40] Like 2011, 2012 is expected to be a bumper year for peaches in Georgia, reflecting an overall favorable trajectory for peaches generally.[40]

The most productive farms for peaches and nectarines, on average, were in Austria. In comparison to world average yield of 13 metric tons per hectare, Austrian farm yields topped 40 metric tonnes per hectare for each of the years between 2006 and 2010, with highest observed average yield of 56.8 metric tonnes per hectare in 2010.[14]

Depending on climate and cultivar, peach harvest can occur from late May into August (Northern Hemisphere); harvest from each tree lasts about a week.

Cultural significance

Peaches are not only a popular fruit, but are symbolic in many cultural traditions, such as in art, paintings and folk tales such as Peaches of Immortality.

China

Peach blossoms are highly prized in Chinese culture. The ancient Chinese believed the peach to possess more vitality than any other tree because their blossoms appear before leaves sprout. When early rulers of China visited their territories, they were preceded by sorcerers armed with peach rods to protect them from spectral evils. On New Year's Eve, local magistrates would cut peach wood branches and place them over their doors to protect against evil influences.[41] Another author writes:

The Chinese also considered peach wood (t'ao-fu) protective against evil spirits, who held the peach in awe. In ancient China, peach-wood bows were used to shoot arrows in every direction in an effort to dispel evil. Peach-wood slips or carved pits served as amulets to protect a person's life, safety, and health.[42]

Peach-wood seals or figurines guarded gates and doors, and, as one Han account recites, "the buildings in the capital are made tranquil and pure; everywhere a good state of affairs prevails."[42] Writes the author, further:

Another aid in fighting evil spirits were peach-wood wands. The Li-chi (Han period) reported that the emperor went to the funeral of a minister escorted by a sorcerer carrying a peach-wood wand to keep bad influences away. Since that time, peach-wood wands have remained an important means of exorcism in China.[42]

Peach kernels (桃仁 táo rén) are a common ingredient used in traditional Chinese medicine to dispel blood stasis, counter inflammation and reduce allergies.[43]

It was in an orchard of flowering peach trees that Liu Bei, Guan Yu, and Zhang Fei took an oath of brotherhood in the opening chapter of the classic Chinese novel Romance of the Three Kingdoms. Another peach forest, the “Peach Blossom Spring” by poet Tao Yuanming is the setting of the favourite Chinese fable and a metaphor of utopias. A peach tree growing on a precipice was where the Taoist master Zhang Daoling tested his disciples.[44] Old Man of the South Pole one of the deity from the Chinese folkreligion Fu Lu Shou is seen holding a large peach, representing long life and health.

Japan

Momotaro, one of Japan's most noble and semihistorical heroes, was born from within an enormous peach floating down a stream. Momotaro or "Peach Boy" went on to fight evil oni and face many adventures.

Korea

In Korea, peaches have been cultivated from ancient times. According to Samguk Sagi, peach trees were planted during the Three Kingdoms of Korea period, and Sallim gyeongje also mentions cultivation skills of peach trees. The peach is seen as the fruit of happiness, riches, honours and longevity. The rare peach with double seeds is seen as a favorable omen of a mild winter. It is one of the ten immortal plants and animals, so peaches appear in many minhwa (folk paintings). Peaches and peach trees are believed to chase away spirits, so peaches are not placed on tables for jesa (ancestor veneration), unlike other fruits.[45][46]

Vietnam

A Vietnamese mythic history states that, in the spring of 1789, after marching to Ngọc Hồi and then winning a great victory against invaders from the Qing Dynasty of China, the King Quang Trung ordered a messenger to gallop to Phú Xuân citadel (now Huế) and deliver a flowering peach branch to the Princess Ngọc Hân. This took place on the fifth day of the first lunar month, two days before the predicted end of the battle. The branch of peach flowers that was sent from the north to the centre of Vietnam was not only a message of victory from the King to his wife, but also the start of a new spring of peace and happiness for all the Vietnamese people. In addition, since the land of Nhật Tân had freely given that very branch of peach flowers to the King, it became the loyal garden of his dynasty.

It was by a peach tree that the protagonists of the Tale of Kieu fell in love. And in Vietnam, the blossoming peach flower is the signal of spring. Finally, peach bonsai trees are used as decoration during Vietnamese New Year (Tết) in northern Vietnam.

Europe

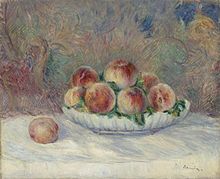

Many famous artists have painted still life with peach fruits placed in prominence. Caravaggio, Vicenzo Campi, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Claude Monet, Édouard Manet, Henri Jean Fantin-Latour, George Forster, James Peale, Severin Roesen, Peter Paul Rubens, Van Gogh are among the many influential artists who painted peaches and peach trees in various settings.[47][48] Scholars suggest that many compositions are symbolic, some an effort to introduce realism.[49] For example, Tresidder claims[50] the artists of Renaissance symbolically used peach to represent heart, and a leaf attached to the fruit as the symbol for tongue, thereby implying speaking truth from one's heart; a ripe peach was also a symbol to imply a ripe state of good health. Caravaggio paintings introduce realism by painting peach leaves that are molted, discolored or in some cases have wormholes - conditions common in modern peach cultivation.[48]

Nutrition and research

| Nutritional value per 100 g (3.5 oz) | |

|---|---|

| Energy | 165 kJ (39 kcal) |

9.54 g | |

| Sugars | 8.39 g |

| Dietary fiber | 1.5 g |

0.25 g | |

0.91 g | |

| Vitamins | Quantity %DV† |

| Vitamin A equiv. | 2% 16 μg2% 162 μg |

| Thiamine (B1) | 2% 0.024 mg |

| Riboflavin (B2) | 2% 0.031 mg |

| Niacin (B3) | 5% 0.806 mg |

| Pantothenic acid (B5) | 3% 0.153 mg |

| Vitamin B6 | 1% 0.025 mg |

| Folate (B9) | 1% 4 μg |

| Choline | 1% 6.1 mg |

| Vitamin C | 7% 6.6 mg |

| Vitamin E | 5% 0.73 mg |

| Vitamin K | 2% 2.6 μg |

| Minerals | Quantity %DV† |

| Calcium | 0% 6 mg |

| Iron | 1% 0.25 mg |

| Magnesium | 2% 9 mg |

| Manganese | 3% 0.061 mg |

| Phosphorus | 2% 20 mg |

| Potassium | 6% 190 mg |

| Sodium | 0% 0 mg |

| Zinc | 2% 0.17 mg |

| Other constituents | Quantity |

| Fluoride | 4 µg |

| †Percentages estimated using US recommendations for adults,[51] except for potassium, which is estimated based on expert recommendation from the National Academies.[52] | |

A medium peach weighs 75 g (2.6 oz) and typically contains 30 Cal, 7 g of carbohydrate (6 g sugars and 1 g fibre), 1 g of protein, 140 mg of potassium, and 8% of the daily value (DV) for vitamin C.[53] Nectarines have a small amount more of vitamin C, provide double the vitamin A, and are a richer source of potassium than peaches.[18]

As with many other members of the rose family, peach seeds contain cyanogenic glycosides, including amygdalin (note the subgenus designation: Amygdalus). These substances are capable of decomposing into a sugar molecule and hydrogen cyanide gas. While peach seeds are not the most toxic within the rose family—that dubious honour going to the bitter almond—large doses of these chemicals from any source are hazardous to human health.

Peach allergy or intolerance is a relatively common form of hypersensitivity to proteins contained in peaches and related fruit (almonds). Symptoms range from local symptoms (e.g. oral allergy syndrome, contact urticaria) to systemic symptoms, including anaphylaxis (e.g. urticaria, angioedema, gastrointestinal and respiratory symptoms).[54] Adverse reactions are related to the "freshness" of the fruit: peeled or canned fruit may be tolerated.

Aroma

More than 80 chemical compounds contribute to the peach aroma. Among others are found C6 gamma-lactones, C8 and C10 (gamma-decalactone), C10 delta-lactone, several esters (such as linalyl butyrate or linalyl formate), acids and alcohols, and benzaldehyde.

In other products

A peach aroma is also a characteristic of some wines such as Saint-Amour Beaujolais wine. It is one of the components of the aroma of Sancerre blanc.

The odour of the synthetic chemical weapon agent cyclosarin is also described as resembling peach.

Phenolic composition

Total phenolics in mg/100 g of fresh weight were 14–102 in white-flesh nectarines, 18–54 in yellow-flesh nectarines, 28–111 in white-flesh peaches, 21–61 in yellow-flesh peaches.[55] The major phenolic compounds identified in peach are chlorogenic acid, (+)-catechin and (-)-epicatechin.[56] Other compounds, identified by HPLC, are gallic acid, neochlorogenic acid, procyanidin B1 and B3, procyanidin gallates, ellagic acid.[57]

Rutin and isoquercetin are the primary flavonols found in Clingstone peaches.[58]

Red-fleshed peaches are rich in anthocyanins[59] of the cyanidin-3-O-glucoside type in six peach and six nectarine cultivars[60] and of the malvin type in the Clingstone variety.[58]

Color

Peach is a color named for the pale color of the interior flesh of the peach fruit.

Trivia

The Peachoid is a four-story (150 feet tall) water tower in Gaffney, South Carolina, United States, that resembles a peach.

Gallery

-

A peach tree in blossom

-

Developing fruit

-

Ripe peaches on a branch

-

Peach blossoms

-

Peach Blossom Close-up

-

Flavorcrest peaches

-

Peach (cultivar 'Berry') – watercolour 1895

-

Harvested peaches

-

White peach and cross section

-

White Georgia Peaches from a farmers market in Starkville, MS

-

The inside of a peach pit

-

Claude Monet, A jar of peaches

-

Van Gogh, Flowering peach tree (1888)

-

Farmer at work in Colorado, 1940

-

Peach blossom

-

Bee tending peach blossoms

References

- ^ "Prunus persica". The Plant List. Version 1. 2010. Retrieved 29 November 2012.

- ^ Faust, M. & Timon, B. Origin and dissemination of peach. Hort. Reviews 17, 331–379 (1995).

- ^ a b c Oregon State University: peaches and nectarines

- ^ "Indian Peaches Information, Recipes and Facts". Specialtyproduce.com. Retrieved 2012-09-24.

- ^ Lyle Campbell, Historical Linguistics: An Introduction, 2nd ed. (Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press, 2004): 274.

- ^ Thacker, Christopher (1985). The history of gardens. Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 57. ISBN 978-0-520-05629-9.

- ^ Singh, Akath; Patel, R.K.; Babu, K.D.; De, L.C. (2007). "Low chiling peaches". Underutilized and underexploited horticultural crops. New Delhi: New India Publishing. p. 90. ISBN 978-81-89422-69-1.

- ^ a b c Geissler, Catherine (2009). The New Oxford Book of Food Plants. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 82. ISBN 978-0-19-160949-7.

- ^ Layne, Desmond R.; Bassi, Daniele (2008). The Peach: Botany, Production and Uses. CAB International. ISBN 978-1-84593-386-9.

- ^ a b Ensminger, Audrey H. (1994). Foods & nutrition encyclopedia. CRC Press. ISBN 0-8493-8980-1.

- ^ Laura Sadori; et al. (2009). "The introduction and diffusion of peach in ancient Italy" (PDF). Edipuglia.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - ^ "George Minifie". Genforum.genealogy.com. 1999-03-21. Retrieved 2012-09-24.

- ^ Verde et al. The high-quality draft genome of peach (Prunus persica) identifies unique patterns of genetic diversity, domestication and genome evolution. Nature Genetics 45, 487–494 (2013) doi:10.1038/ng.2586

- ^ a b c "Major Food And Agricultural Commodities And Producers - Countries By Commodity". Fao.org. 2011. Retrieved 2013-11-06.

- ^ "Deciduous Fruit Production - India (see Peach section), FAO United Nations". Fao.org. Retrieved 2012-09-24.

- ^ Szalay, L., Papp, J., and Szaóbo, Z. (2000). Evaluation of frost tolerance of peach varieties in artificial freezing tests. In: Geibel, M., Fischer, M., and Fischer, C. (eds.). Eucarpia symposium on Fruit Breeding and Genetics. Acta Horticulturae 538. Abstract.

- ^ "Peach tree physiology" (PDF). University of Georgia. 2007.

- ^ a b c "Peach and Nectarine Culture". University of Rhode Island. 2000.

- ^ W.R. Okie (2005). "Varieties - Peaches" (PDF). United States Department of Agriculture.

- ^ "RHS Plant Selector Prunus persica 'Duke of York' (F) AGM / RHS Gardening". Apps.rhs.org.uk. Retrieved 2012-09-24.

- ^ "RHS Plant Selector Prunus persica 'Peregrine' (F) AGM / RHS Gardening". Apps.rhs.org.uk. Retrieved 2012-09-24.

- ^ "RHS Plant Selector Prunus persica 'Rochester' (F) AGM / RHS Gardening". Apps.rhs.org.uk. Retrieved 2012-09-24.

- ^ "RHS Plant Selector Prunus persica var. nectarina 'Lord Napier' (F) AGM / RHS Gardening". Apps.rhs.org.uk. Retrieved 2012-09-24.

- ^ a b McCraw, Dean ((unknown date)). "Planting and Early Care of the Peach Orchard". Oklahoma Cooperative Extension Service. Retrieved February 13, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Livio Trainotti, Alice Tadiello and Giorgio Casadoro* (2007-10-08). "The involvement of auxin in the ripening of climacteric fruits comes of age: the hormone plays a role of its own and has an intense interplay with ethylene in ripening peaches". Jxb.oxfordjournals.org. Retrieved 2012-09-24.

- ^ "1-MCP effects on ethylene emission and fruit quality traits of peaches and nectarines - Springer". Springerlink.com. Retrieved 2013-04-22.

- ^ "Prunus persica, peach, nectarine: taxonomy, facts, life cycle, fruit anatomy at GeoChemBio". Geochembio.com. Retrieved 2012-09-24.

- ^ "Healthy and Sustainable Food | The Center for Health and the Global Environment". Chge.med.harvard.edu. 2011-11-16. Retrieved 2012-09-24.

- ^ Oxford English Dictionary

- ^ Fairchild, David (1938). The World Was My Garden. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. p. 226.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ "Fruit Trees Australia". Peacherine Fruit Tree. fruit-trees-australia.com.au. Retrieved November 21, 2011.

- ^ "Koanga Institute". Almonds, Nectarines, Peacherines and Apricots. koanga.org.nz. Retrieved November 21, 2011.

- ^ Louise Pound (1920). "Stunts in language". The English Language. 9 (2). JSTOR 802441.

- ^ Fort Valley State University College of Agriculture: Peaches

- ^ Georgia Peach: Georgia Peach Study

- ^ "Growers left in lurch as CanGro plant closures go ahead". Betterfarming.com. 2008-04-01. Retrieved 2012-09-24.

- ^ "The Peach: 10 Healthy Facts". Webmd.com. 2010-07-08. Retrieved 2012-09-24.

- ^ "Ga. blueberry knocks peach off top of fruit pile", Associated Press, published on Yahoo News On-Line, July 22, 2013

- ^ http://georgiainfo.galileo.usg.edu/gahistmarkers/samuelrumphhistmarker.htm

- ^ a b 05/04/2012 1:16:48 PMDoug Ohlemeier. "Watermelon, peaches, blueberries ramp up in Georgia". The Packer. Retrieved 2012-09-24.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Doré S.J., Henry; Kennelly, S.J. (Translator), M. (1914). Researches into Chinese Superstitions. Tusewei Press, Shanghai.

{{cite book}}:|last2=has generic name (help) Vol V p. 505 - ^ a b c Food in China: A Cultural and Historical Inquiry, by Frederick J. Simoons, 1991, Page 218, isbn=084938804X.

- ^ "TCM: Peach kernels" (in Chinese). Retrieved November 1, 2010.

- ^ Stephen Eskildsen (1998). Asceticism in early taoist religion. SUNY Press. p. 26. ISBN 978-0-7914-3955-5. Retrieved 28 June 2011.

- ^ "한국에서의 복숭아 재배" (in Korean). Nate / Britannica. Retrieved 2010-01-12.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ "복숭아" (in Korean). Nate / Encyclopedia of Korean Culture. Retrieved 2010-01-12.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ Janet M. Torpy (2010). "Still Life With Peaches". JAMA. 303 (3): 203–203. doi:10.1001/jama.2009.1853.

- ^ a b "Caravaggio's Fruit: A Mirror on Baroque Horticulture - Jules Janick" (PDF). Retrieved 2012-09-24.

- ^ Aaron H. de Groft (2006). "Caravaggio - Still Life with Fruit on a Stone Ledge (Book: Papers of the Muscarelle Museum of Art, Volume 1)" (PDF).

- ^ Jack Tresidder (2004). 1,001 Symbols: An Illustrated Guide to Imagery and Its Meaning. ISBN 978-0811842822.

- ^ United States Food and Drug Administration (2024). "Daily Value on the Nutrition and Supplement Facts Labels". Retrieved 2024-03-28.

- ^ National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; Health and Medicine Division; Food and Nutrition Board; Committee to Review the Dietary Reference Intakes for Sodium and Potassium (2019). Oria, Maria; Harrison, Meghan; Stallings, Virginia A. (eds.). Dietary Reference Intakes for Sodium and Potassium. The National Academies Collection: Reports funded by National Institutes of Health. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US). ISBN 978-0-309-48834-1. PMID 30844154.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ USDA Handbook No. 8

- ^ "Article on Peach allergy, M. Besler et al". Food-allergens.de. Retrieved 2012-09-24.

- ^ Template:Cite PMID

- ^ Browning Potential, Phenolic Composition, and Polyphenoloxidase Activity of Buffer Extracts of Peach and Nectarine Skin Tissue. Guiwen W. Cheng and Carlos H. Crisosto, J. Amer. Soc. Hort. Sci., 1995, 120(5), pages 835–838, (article)

- ^ Postharvest sensory and phenolic characterization of ‘Elegant Lady’ and ‘Carson’ peaches. Rodrigo Infante, Loreto Contador, Pía Rubio, Danilo Aros and Álvaro Peña-Neira, Chilean Journal Of Agricultural Research, 71(3), July–September 2011, pages 445-451 (article)

- ^ a b Chang, S; Tan, C; Frankel, EN; Barrett, DM (2000). "Low-density lipoprotein antioxidant activity of phenolic compounds and polyphenol oxidase activity in selected clingstone peach cultivars". Journal of agricultural and food chemistry. 48 (2): 147–51. PMID 10691607.

- ^ Selecting new peach and plum genotypes rich in phenolic compounds and enhanced functional properties. Bolivar A. Cevallos-Casals, David Byrne, William R. Okie and Luis Cisneros-Zevallos, Food Chemistry, 2006, 96, pages 273–328, doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2005.02.03

- ^ Phenolic compounds in peach (Prunus persica) cultivars at harvest and during fruit maturation. C. Andreotti, D. Ravaglia, A. Ragaini and G. Costa, Annals of Applied Biology, Volume 153, Issue 1, pages 11–23, August 2008, doi:10.1111/j.1744-7348.2008.00234.x

- Huxley, A., ed. (1992). New RHS Dictionary of Gardening. Macmillan ISBN 0-333-47494-5.