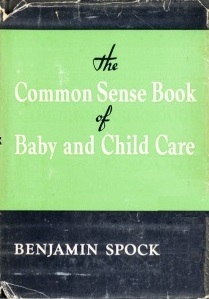

The Common Sense Book of Baby and Child Care

First edition | |

| Author | Benjamin Spock |

|---|---|

| Language | English |

| Subject | Child care |

| Publisher | Duell, Sloan and Pearce (New York City) |

Publication date | 14 July 1946 |

| Publication place | USA |

| Pages | 527 (1st edition) |

| OCLC | 61584207 |

The Common Sense Book of Baby and Child Care is a book by American pediatrician Benjamin Spock and one of the best-selling books of the twentieth century, selling 500,000 copies in the six months after its initial publication in 1946 and 50 million by the time of Spock's death in 1998.[1] As of 2011, the book had been translated into 39 languages.[2]

Spock and his manual helped revolutionize child-rearing methods for the post-World War II generation. Mothers heavily relied on Spock's advice and appreciated his friendly, reassuring tone.[3] Spock emphasizes in his book that, above all, parents should have confidence in their abilities and trust their instincts. The famous first line of the book reads, "Trust yourself. You know more than you think you do."[4]

History

Child care before Spock

Spock's book helped revolutionize child care in the 1940s and 1950s. Prior to this, rigid schedules permeated pediatric care. Influential authors like behavioral psychologist John B. Watson, who wrote Psychological Care of Infant and Child in 1928, and pediatrician Luther Emmett Holt, who wrote The Care and Feeding of Children: A Catechism for the Use of Mothers and Children's Nurses in 1894, told parents to feed babies on specific schedules and start toilet training at an early, specific age.[5][6] Watson, Holt, and other child care experts obsessed over rigidity because they believed that irregularities in feeding and bowel movements were causing the widespread diarrheal diseases seen among babies in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.[7]

Furthermore, these experts, whose ideas were embodied in Infant Care pamphlets distributed by the U.S. government, warned against "excessive" affection by parents for their children.[8] To maintain sterility and to prevent children from becoming spoiled or fussy, these experts recommended kissing children only on the forehead and limiting hugs or other displays of affection.[9][10]

Intent

As a practicing pediatrician in the 1930s, Spock noticed that prevailing methods in pediatric care seemed cruel and ignored the emotional needs of the child. He wanted to explore the psychological reasons behind common problems seen during practices like breastfeeding and toilet training, in order to give less arbitrary advice to mothers who came to his practice. He thus became trained in psychoanalysis, emerging as the first pediatrician with a psychoanalytic background. Seeking useful ways to implement Freudian philosophy into child-rearing practices, Spock would try out his advice on patients and their mothers, continuously seeking their response.[11] He contradicted contemporary norms in child care by supporting flexibility instead of rigidity and encouraging parents to show affection for their children.[12]

Although Spock was approached to write a child-care manual in 1938 by Doubleday, he did not yet feel certain enough of his professional abilities to accept the offer. Eventually, though, after several more years of giving advice to mothers, Spock felt more convinced of his advice and published a paperback copy of The Common Sense Book of Baby and Child Care in 1946 with Pocket Books.[13] His intent in writing the book was to disseminate comprehensive information to all mothers, giving advice that combined the physical and psychological aspects of child care. So that any mother could afford it, the book was sold at just twenty-five cents.[14]

Synopsis

The Common Sense Book of Baby and Child Care is arranged by topics corresponding to the child's age, ranging from infancy to teenage years. Drawn from his career as a pediatrician, Spock's advice is comprehensive, dealing with topics such as preparing for the baby, toilet training, school, illnesses, and "special problems" like "separated parents" and "the fatherless child".[15]

Unlike leading child care experts prior to the 1940s, Spock supports flexibility in child-rearing, advising parents to treat each child as an individual. Drawing on his psychoanalytic training, he explains the behavior and motivations of children at each stage of growth, allowing parents to make their own decisions about how to raise their children. For example, Spock has an entire chapter devoted to "The One-Year-Old," in which he explains that babies at this age like to explore the world around them. He then suggests ways to arrange the house and prevent accidents with a "wandering baby."[16]

Spock emphasizes that ultimately, the parents' "natural loving care" for their children is most important.[17] He reminds parents to have confidence in their abilities and to trust their common sense; his practice as a pediatrician had proven to him that parents' instincts were usually best.[18]

Revised editions

During Spock's lifetime, seven editions of his book were published. Several co-authors have helped revise the book since the fifth edition. Since Spock's death in 1998, three more editions have been published.

- Spock, Benjamin (1957). Baby and Child Care (2nd ed.). New York: Pocket Books. ISBN 0671646699.

- Spock, Benjamin (1968). Baby and Child Care (3rd ed.). London: Bodley Head. ISBN 0-370-00271-7. OCLC 97196.

- Spock, Benjamin (1976). Baby and Child Care (4th ed.). New York City: Pocket Books. ISBN 0-671-79003-X. OCLC 173465714.

- Spock, Benjamin; Rothenberg, Michael B. (1985). Dr. Spock's Baby and Child Care for the Nineties (5th ed.). New York City: E.P. Dutton. ISBN 0-525-24312-7. OCLC 11788917.

- Spock, Benjamin; Rothenberg, Michael B. (1992). Dr. Spock's Baby and Child Care (6th ed.). New York City: Dutton. ISBN 0-525-93400-6. OCLC 25535213.

- Spock, Benjamin; Parker, Steven (1998). Dr. Spock's Baby and Child Care (7th ed.). New York City: Pocket Books. ISBN 0-525-94417-6. OCLC 38965990.

- Spock, Benjamin; Robert Needlman (2004). Dr. Spock's Baby and Child Care (8th ed.). New York: Pocket Books. ISBN 0743476689.

- Spock, Benjamin; Robert Needlman (2012). Dr. Spock's Baby and Child Care (9th ed.). New York: Gallery Books. ISBN 978-1439189283.

- Spock, Benjamin; Robert Needlman (2018). Dr. Spock's Baby and Child Care (10th ed.). New York: Gallery Books. ISBN 9781501175336.

Each subsequent edition of the book brings medical information up-to-date. Other revisions have emerged to deal with contemporary social issues, such as daycare and gay parenting.[19]

In the second edition, Spock emphasizes in several new chapters the importance of "firm but gentle" control of children.[20] He warns against self-demand feeding, a type of feeding that had become popular in the 1940s. Because parents were letting their baby dictate when he or she should be fed, some parents began indulging all of their child's desires, resulting in unregulated sleep schedules and a loss of control for the parents. Spock clarifies in his manual that while parents should respect their children, they also must ask for respect in return.[21]

By the fourth edition, Spock adapts to society's shifting ideas of gender equality, especially after the rise of the women's liberation movement and concurrent feminist criticisms about sexism apparent in Baby and Child Care. Spock changed every pronoun for the baby, previously referred to only as "he", and discusses ways for parents to minimize gender stereotyping while raising a child.[22] He warns against praising girls only on their appearance and notes the sexism present in a household where girls learn to do housework while boys play outside. Spock also continues to expand on the role of fathers and acknowledges that parents should have an equal share in child-rearing responsibilities, while also both having the right to work.[23]

In the seventh edition, Spock endorses a low-fat, plant-based diet for children due to rising trends in obesity and Spock's own switch to a macrobiotic diet after facing serious health issues.[24]

Reaction

Within a year of being published, The Common Sense Book of Baby and Child Care had already sold 750,000 copies, mostly by word-of-mouth advertising.[25] Mothers appreciated that Spock was not condescending in his writing and instead very empathetic towards mothers, acknowledging how tiresome child care can be.[3] Although he believed that much of a child's personality and behavior rested in the parents' hands, he did not scare parents with this large responsibility of raising a "good" child, like earlier child care experts had.[26] He was lauded for writing with a friendly, reassuring tone and using conversational, easy-to-read language.[27]

Spock was popularized by mentions in household magazines and famous television shows, such as I Love Lucy, where the characters Lucy and Ricky Ricardo were seen consulting Spock's manual in various episodes when seeking advice for raising their child.[25] Spock quickly became a household name in the 1950s and is frequently credited for helping to raise a generation of "Spock babies" in the post-war period. Mothers heavily relied on his advice; by 1956, The Common Sense Book of Baby and Child Care was already selling a million copies each year.[28]

By the mid-1960s, however, book sales quickly slowed due to Spock's tarnished reputation after his publicized involvement in protests of the Vietnam War. Skepticism of his work increased, especially among colleagues, who criticized Spock for not being a serious academic researcher and relying too heavily on anecdotal evidence in his book.[29]

By the late 1960s, Spock faced widespread criticism for condoning an overly permissive parenting style. Many commentators blamed Spock for helping to create the counterculture of the 1960s. Critics believed the current youth were rebellious and defiant in part because they had been brought up by Baby and Child Care. Spock, however, continued to defend himself, saying he had always believed in firm leadership by parents.[30]

In the 1970s, with the rise of the women's liberation movement, feminists began to publicly criticize Spock for the sexist philosophy apparent in his book. Spock was thus forced to confront his own ideas about gender roles and gender stereotyping.[22]

Near the end of his life, Spock's changing ideas were reflected alongside technological and social changes in the seventh and final edition of his book.[31] His advocacy for a vegan diet drew criticism from some nutritionists and pediatricians, including co-author Dr. Steven J. Parker, as being too extreme.[32] Health and science columnist Jane Brody referenced the Pediatric Nutrition Handbook of the AAP in arguing that a vegan diet for young children could result in nutritional deficiencies unless carefully planned, something which would be difficult for working parents.[33]

Legacy

Baby and Child Care popularized new ideas about child care in the years following World War II, encouraging flexibility, common sense, affection, and Freudian philosophy. Spock's reassuring advice gave parents the confidence to use their best judgment to raise their children.[34] Spock also masked Freudian explanations of children's behavior in plainspoken language to avoid offending his readers, making Freud accessible to mainstream America.[35] In 1959, Look magazine praised Spock, noting that "perhaps no other person has so influenced an entire nation’s ideas about babies…His views have brought naturalness, common sense, reassurance, Sigmund Freud and even joy to parents all over the world".[36]

Spock's optimistic book reflects the hopefulness of the post-war period and society's focus on children. Because post-war affluence helped parents give children more opportunities, parents became more concerned with providing the best for their children. At the same time, the widespread move to the suburbs broke up families, increasing parents' reliance on experts' advice over grandparents' advice.[37]

Although Spock's reputation has changed over time, he continued to be a leading authority on child care until his death. In 1990, Life magazine named Spock one of the 100 most important people of the twentieth century.[38] Upon Spock's death in 1998, The New York Times noted that "babies do not arrive with owner’s manuals…. But for three generations of American parents, the next best thing was Baby and Child Care…Dr. Benjamin Spock…breathed humanity and common sense into child-rearing".[39]

The book promoted prone sleeping for babies. This greatly increases a baby's risk of dying from sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS). Such advice led to over 60,000 deaths worldwide.[40][41]

Notes

- ^ Thomas Maier, Dr. Spock: An American Life (New York: Basic Books, 2003), 462.

- ^ Louise Hidalgo, "Dr. Spock's Baby and Child Care at 65," BBC World Service, 23 August 2011.

- ^ a b Maier, 142.

- ^ Benjamin Spock, The Common Sense Book of Baby and Child Care (New York: Duell, Sloan, and Pearce, 1946).

- ^ John Watson, Psychological Care of Infant and Child, (New York: W. W. Norton & Co., 1928).

- ^ Luther Emmett Holt, The Care and Feeding of Children, (New York: D. Appleton & Co., 1894).

- ^ Benjamin Spock, "How My Ideas Have Changed," Redbook, October 1963.

- ^ United States Department of Labor, "Infant Care," Infant Care, Washington, DC (1922).

- ^ Watson.

- ^ Holt.

- ^ Maier, 123.

- ^ Spock, "How My Ideas Have Changed."

- ^ Benjamin Spock and Mary Morgan, Spock on Spock: A Memoir of Growing up With the Century (New York: Pantheon Books, 1989), 133.

- ^ Maier, 128.

- ^ Spock, Baby and Child Care.

- ^ Spock, Baby and Child Care, 207–209.

- ^ Spock,Baby and Child Care, 3.

- ^ Spock, Baby and Child Care, 4.

- ^ Maier, 402.

- ^ Maier, 206.

- ^ Maier, 206–210.

- ^ a b Spock and Morgan, 247.

- ^ Maier, 377.

- ^ Maier, 452.

- ^ a b Spock and Morgan, 137.

- ^ Spock and Morgan, 135.

- ^ International Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences, 2nd ed.., s.v. "Spock, Benjamin 1903–1998."

- ^ Maier, 200.

- ^ Maier, 260.

- ^ Spock and Morgan, 263.

- ^ "Word for Word / Dr. Spock; Time to Change the Baby Advice: Evolution of a Child-Care Icon". The New York Times. 22 March 1998.

- ^ Beck, Joan. "DR. SPOCK'S IRRESPONSIBLE LEGACY". chicagotribune.com.

- ^ Jane Brody, "Personal Health," The New York Times, 30 June 1998.

- ^ Spock and Morgan, 241.

- ^ Maier, 135.

- ^ Gereon Zimmermann, "A Visit With Dr. Spock," Look, 21 July 1959.

- ^ Maier, 201.

- ^ Maier, 457.

- ^ "Dr. Spock's Children," The New York Times, 17 March 1998.

- ^ Bovbjerg, Marit L. (2011). "Rethinking Dr. Spock". American Journal of Public Health. 101 (10): 1812, author reply 1812-3. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2011.300336. PMC 3222341. PMID 21852654.

- ^ Gilbert, Ruth; Salanti, Georgia; Harden, Melissa; See, Sarah (2005). "Infant sleeping position and the sudden infant death syndrome: systematic review of observational studies and historical review of recommendations from 1940 to 2002". International Journal of Epidemiology. 34 (4): 874–887. doi:10.1093/ije/dyi088. PMID 15843394.

References

- Brody, Jane. “Personal Health; Feeding Children off the Spock Menu.” The New York Times, 30 June 1998.

- "Dr. Spock's Children." The New York Times, 17 March 1998.

- Hidalgo, Louise. "Dr. Spock's Baby and Child Care at 65." BBC World Service, 23 August 2011.

- Holt, Luther Emmett. The Care and Feeding of Children: A Catechism for the Use of Mothers and Children’s Nurses. New York: D. Appleton & Co., 1894.

- International Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences, 2nd ed., s.v. "Spock, Benjamin 1903–1998." Detroit: MacMillan Reference USA, 2008. pp. 61–63.

- Maier, Thomas. Dr. Spock: An American Life. New York: Basic Books, 2003.

- Spock, Benjamin. The Common Sense Book of Baby and Child Care. New York: Duell, Sloan, and Pearce, 1946.

- Spock, Benjamin. "How My Ideas Have Changed." Redbook, October 1963.

- Spock, Benjamin, and Morgan, Mary. Spock on Spock: A Memoir of Growing Up with the Century. New York: Pantheon Books, 1989.

- United States. Children's Bureau. "Infant Care," Infant Care, Washington, DC, no. 8.

- Watson, John B. Psychological Care of Infant and Child. New York: W. W. Norton & Co., 1928.

- Zimmermann, Gereon. "A Visit with Dr. Spock." Look, 21 July 1959.