Arvanites: Difference between revisions

KaragouniS (talk | contribs) rv:stop adding this kind of stuff |

the edit was correct, nothing of the information was inaccurate: restoring |

||

| Line 12: | Line 12: | ||

----substantial changes.--------------------------------------------------* |

----substantial changes.--------------------------------------------------* |

||

************************************************************************--> |

************************************************************************--> |

||

'''Arvanites''' ([[Greek language|Greek]]: Αρβανίτες, see also [[#Names|below]] about names) are a population group in [[Greece]] who traditionally speak ''[[Arvanitika]]'', a form of [[Albanian language|Albanian]]. They settled in Greece during the late [[Middle Ages]] and were the predominant population element of some regions in the south of Greece through the [[19th century]]. Today, Arvanites have become largely assimilated and self-identify as Greeks. Arvanitika is under danger of extinction due to language shift towards Greek and due to large-scale migrations into the cities. |

'''Arvanites''' ([[Greek language|Greek]]: Αρβανίτες, see also [[#Names|below]] about names) are a population group in [[Greece]] who traditionally speak ''[[Arvanitika]]'', a form of [[Albanian language|Albanian]]. They are the ancestors of the [[Arbëresh]] community of Italy and Sicily. They settled in Greece during the late [[Middle Ages]] and were the predominant population element of some regions in the south of Greece through the [[19th century]]. Today, Arvanites have become largely assimilated and self-identify as Greeks. Arvanitika is under danger of extinction due to language shift towards Greek and due to large-scale migrations into the cities. |

||

==History== |

==History== |

||

| Line 27: | Line 27: | ||

In the 17th and 18th centuries, Arvanites from Epirus constituted a prominent element in the establishment of the effectively independent state of the [[Souliotes]] in the mountains of [[Epirus (region)|Epirus]],<ref>Biris 1960 has an extensive analysis about Suli and the phares of Suliots.</ref> which resisted Ottoman domination. During the [[Greek War of Independence]], many Arvanites played an important role fighting on the Greek side against the Ottomans, often as national Greek heroes. With the formation of modern nations and nation-states in the Balkans, Arvanites have come to be regarded as an integral part of the Greek nation. In [[1899]], leading representatives of the Arvanites in Greece, among them descendants of the independence heroes Botsaris and Tzavelas, published a manifesto calling their fellow Albanians outside Greece to join in the creation of a common Albanian-Greek state.<ref>First published in ''Ελληνισμός'', Athens 1899, 195-202. Quoted in Gkikas 1978:7-9.</ref> In [[1903]], Arvanites like Vangelis Koropoulis (from Mandra Attica) participated in the [[Macedonian Struggle]].<ref>Stamou, Ch. ''Μακεδονικός Αγώνας (1903-08)''. ''...θα αγωνισθώ μέχρι να ελευθερωθεί η Μακεδονία και θα πεθάνω εδώ...''</ref> |

In the 17th and 18th centuries, Arvanites from Epirus constituted a prominent element in the establishment of the effectively independent state of the [[Souliotes]] in the mountains of [[Epirus (region)|Epirus]],<ref>Biris 1960 has an extensive analysis about Suli and the phares of Suliots.</ref> which resisted Ottoman domination. During the [[Greek War of Independence]], many Arvanites played an important role fighting on the Greek side against the Ottomans, often as national Greek heroes. With the formation of modern nations and nation-states in the Balkans, Arvanites have come to be regarded as an integral part of the Greek nation. In [[1899]], leading representatives of the Arvanites in Greece, among them descendants of the independence heroes Botsaris and Tzavelas, published a manifesto calling their fellow Albanians outside Greece to join in the creation of a common Albanian-Greek state.<ref>First published in ''Ελληνισμός'', Athens 1899, 195-202. Quoted in Gkikas 1978:7-9.</ref> In [[1903]], Arvanites like Vangelis Koropoulis (from Mandra Attica) participated in the [[Macedonian Struggle]].<ref>Stamou, Ch. ''Μακεδονικός Αγώνας (1903-08)''. ''...θα αγωνισθώ μέχρι να ελευθερωθεί η Μακεδονία και θα πεθάνω εδώ...''</ref> |

||

During the [[20th century]], after the creation of the Albanian nation-state, Arvanites in Greece have come to dissociate themselves much more strongly from Albanians, stressing instead their national self-identification as Greeks. Many are reported to find their designation as "Albanians", or that of their language as "Albanian", offensive.<ref>GHM 1995.</ref> At the same time, it has been reported that many Arvanites in past decades have maintained a stance of social self-deprecation, leading to a progressive loss of their traditional language and a shifting of the younger generation towards Greek. At some times, particularly under the nationalist [[Ioannis Metaxas|Metaxas]] dictatorship of [[1936]] - [[1940]], Greek state institutions followed a policy of actively discouraging and repressing the use of Arvanitika.<ref>GHM 1995, Trudgill/Tzavaras 1977. See also Tsitsipis 1981, Botsi 2003.</ref> However, during the [[1940s]], the position of the Arvanites improved to an extent since a number of them aided Greek soldiers and military officers who were serving on the Albanian front. During the [[1950s]], [[1960s]], and early [[1970s]], many Arvanites were forced to adopt katharevousa as the language of Greek nationality and identity. This trend was especially prevalent during the [[Greek military junta|Greek military junta (1967-1974)]].<ref>Gefou-Madianou, page 420.</ref> |

During the [[20th century]], after the creation of the Albanian nation-state, Arvanites in Greece have come to dissociate themselves much more strongly from Albanians, stressing instead their national self-identification as Greeks. Many are reported to find their designation as "Albanians", or that of their language as "Albanian", offensive.<ref>GHM 1995.</ref> This is in particular reference to the [[Albanian language|Albanian]] term "[[Shqiptar]]" which has been used in Albania since the time of [[Skanderbeg]] in reference to the Albanian people. The term "shqiptar" was never taken on by the [[Arvanites]] and subsequent [[Arbëresh]] because post-Skanderbeg history is not shared with Arvanites and other Albanians. The "Albanian" (shqiptar) referred to in Albania in the Albanian language is not a self-designation of [[Arvanites]] and [[Arbëresh]], and has connotations with the [[Ottoman]] and 20th Century Albanian heritage which is alien to Arvanites. At the same time, it has been reported that many Arvanites in past decades have maintained a stance of social self-deprecation, leading to a progressive loss of their traditional language and a shifting of the younger generation towards Greek. At some times, particularly under the nationalist [[Ioannis Metaxas|Metaxas]] dictatorship of [[1936]] - [[1940]], Greek state institutions followed a policy of actively discouraging and repressing the use of Arvanitika.<ref>GHM 1995, Trudgill/Tzavaras 1977. See also Tsitsipis 1981, Botsi 2003.</ref> However, during the [[1940s]], the position of the Arvanites improved to an extent since a number of them aided Greek soldiers and military officers who were serving on the Albanian front. During the [[1950s]], [[1960s]], and early [[1970s]], many Arvanites were forced to adopt katharevousa as the language of Greek nationality and identity. This trend was especially prevalent during the [[Greek military junta|Greek military junta (1967-1974)]].<ref>Gefou-Madianou, page 420.</ref> |

||

==Demographics== |

==Demographics== |

||

| Line 56: | Line 56: | ||

==Names== |

==Names== |

||

The name '''Arvanites''' and its equivalents are today used both in Greek (''Αρβανίτες'', singular form ''Αρβανίτης'', feminine ''Αρβανίτισσα'') and in Arvanitic itself ('''Arbëreshë''' or '''Arbërorë'''). In Standard Albanian, the name is '''Arvanitë'''. Arvanites are thus distinguished from ethnic Albanians, who are called '''Shqiptarë''' in Standard Albanian, and '''Alvaní''' (Αλβανοί) in Greek. Arvanites have referred to their place of origin as '''Arvanitiá''' (today southern Albania and NW Greece). Sometimes this term has also been applied to the whole of Albania and/or Epirus. |

The name '''Arvanites''' and its equivalents are today used both in Greek (''Αρβανίτες'', singular form ''Αρβανίτης'', feminine ''Αρβανίτισσα'') and in Arvanitic itself ('''Arbëreshë''' or '''Arbërorë'''). In Standard Albanian, the name is '''Arvanitë'''. Arvanites are thus distinguished from ethnic Albanians, who are called '''Shqiptarë''' in Standard Albanian, and '''Alvaní''' (Αλβανοί) in Greek. Arvanites have referred to their place of origin as '''Arvanitiá''' in Greek and '''Arbëria''' in Arvanitic itself (today southern Albania and NW Greece). Sometimes this term has also been applied to the whole of Albania and/or Epirus. |

||

The name '''Arvanites''' and its equivalents go back to an old ethnonym that was at one time used by all Albanians to refer to themselves. It goes back to a geographical term, first attested in [[Polybius]] in the form of a place-name Άρβων, and then again in Byzantine authors of the 11th and 12th centuries in the form Άρβανον or Άρβανα, referring to a place in what is today Albania.<ref>[[Michael Attaliates]], ''Ιστορία'' 297 mentiones "Arbanitai" as parts of a mercenary army (c.1085); [[Anna Comnena]], ''Αλεξιάς'', VI:7/7 and XIII 5/1-2 mentions a region or town called Arbanon or Arbana, and "Arbanitai" as its inhabitants (1148). See also Vranousi (1970) and Ducellier (1968).</ref> "Arvanites" ("Arbanitai") originally referred to the inhabitants of that region, and then to all Albanian-speakers. The alternative name "Albanians" (Αλβανοί) may ultimately be etymologically related, but is of less clear origin (see [[Albania (toponym)]]). It was probably conflated with that of the "Arbanitai" at some stage due to phonological similarity. In later Byzantine usage, the terms "Arbanitai" and "Albanoi", with a range of variants, were used interchangeably, while sometimes the same groups were also called by the classicising names "Illyrians" or "Macedonians". In the 19th and early 20th century, Αλβανοί ("Albanians") was used predominantly in formal registers and Αρβανίτες ("Arvanites") in the more popular speech in Greek, but both were used indiscriminately for both Muslim and Christian Albanophones inside and outside Greece. In Albania itself, the self-designation "Arvanites" had been exchanged for the new name "Shqiptarë" since the 15th century, an innovation that was not shared by the Albanophone migrant communities in the south of Greece. In the course of the 20th century, it became customary to use only "Αλβανοί" for the people of Albania, and only "Αρβανίτες" for the Christian Arvanites integrated into Greek society, thus stressing the national separation between the two groups. |

The name '''Arvanites''' and its equivalents go back to an old ethnonym that was at one time used by all Albanians to refer to themselves. It goes back to a geographical term, first attested in [[Polybius]] in the form of a place-name Άρβων, and then again in Byzantine authors of the 11th and 12th centuries in the form Άρβανον or Άρβανα, referring to a place in what is today Albania.<ref>[[Michael Attaliates]], ''Ιστορία'' 297 mentiones "Arbanitai" as parts of a mercenary army (c.1085); [[Anna Comnena]], ''Αλεξιάς'', VI:7/7 and XIII 5/1-2 mentions a region or town called Arbanon or Arbana, and "Arbanitai" as its inhabitants (1148). See also Vranousi (1970) and Ducellier (1968).</ref> "Arvanites" ("Arbanitai") originally referred to the inhabitants of that region, and then to all Albanian-speakers. The alternative name "Albanians" (Αλβανοί) may ultimately be etymologically related, but is of less clear origin (see [[Albania (toponym)]]). It was probably conflated with that of the "Arbanitai" at some stage due to phonological similarity. In later Byzantine usage, the terms "Arbanitai" and "Albanoi", with a range of variants, were used interchangeably, while sometimes the same groups were also called by the classicising names "Illyrians" or "Macedonians". In the 19th and early 20th century, Αλβανοί ("Albanians") was used predominantly in formal registers and Αρβανίτες ("Arvanites") in the more popular speech in Greek, but both were used indiscriminately for both Muslim and Christian Albanophones inside and outside Greece. In Albania itself, the self-designation "Arvanites" had been exchanged for the new name "Shqiptarë" since the 15th century, an innovation that was not shared by the Albanophone migrant communities in the south of Greece. In the course of the 20th century, it became customary to use only "Αλβανοί" for the people of Albania, and only "Αρβανίτες" for the Christian Arvanites integrated into Greek society, thus stressing the national separation between the two groups. |

||

| Line 214: | Line 214: | ||

[[Category:Ethnic groups in Greece]] |

[[Category:Ethnic groups in Greece]] |

||

[[Category:Arvanites]] |

[[Category:Arvanites]] |

||

[[Category:History of Albania]] |

|||

[[de:Arvaniten]] |

[[de:Arvaniten]] |

||

Revision as of 06:59, 29 August 2007

| |

| Regions with significant populations | |

|---|---|

| Greece | |

| Languages | |

| Arvanitika, Greek | |

| Religion | |

| Greek Orthodox |

Arvanites (Greek: Αρβανίτες, see also below about names) are a population group in Greece who traditionally speak Arvanitika, a form of Albanian. They are the ancestors of the Arbëresh community of Italy and Sicily. They settled in Greece during the late Middle Ages and were the predominant population element of some regions in the south of Greece through the 19th century. Today, Arvanites have become largely assimilated and self-identify as Greeks. Arvanitika is under danger of extinction due to language shift towards Greek and due to large-scale migrations into the cities.

History

Arvanites in Greece originated from Albanian settlers who moved south at different times between the 14th and the 16th centuries from areas in what is today southern Albania.[1][2]

The reasons for this migration are not entirely clear and may be manifold. In many instances the Arvanites were invited by the Byzantine and Latin rulers of the time. They were employed to re-settle areas that had been largely depopulated through wars, epidemics and other reasons, and they were employed as soldiers. Some later movements are also believed to have been motivated to evade Islamization after the Ottoman conquest. The main waves of migration into southern Greece started around 1300, reached a peak some time during the 14th century, and ended around 1600.[3] Arvanites first reached Thessaly, then Attica and finally the Peloponnese.[4]

In many instances, Arvanite groups placed themselves in the services of local Greek rulers who were descendants of Byzantine noble dynasties. During the 15th and 16th centuries, such groups were renowned as mercenaries, the so-called Stradioti, serving in the armies of the Venetian Republic. Some also fought in European armies further afield, like that of Henry VIII of England. Many of them became bilingual and culturally assimilated to the Greeks.[5] Arvanites also held positions in many Greek Orthodox churches. In 1697, Michael Bouas and Alexander Moscholeon not only chronicled their positions in the Greek Orthodox Church of Naples, but they also professed their Greek identity.[6]

In areas such as Messogia, many Arvanitic-speaking populations did not see language as the defining criterion of their Greek identity. Their sense of identity relied upon their adherence to the Greek Orthodox Church, their sense of localism with ties to the land, and their sense of kinship. All of these attributes had long served as cohesive elements of identity within the Ottoman Empire, which provided the Arvanites the ability to establish a form of ethnic unity and a stronger form of Greek self-identification.[7] Throughout the Ottoman period, the Arvanites always maintained their ethnic Greek identity, as well as their loyalty to the Greek Orthodox Church during their conflicts against the Ottomans.

In the 17th and 18th centuries, Arvanites from Epirus constituted a prominent element in the establishment of the effectively independent state of the Souliotes in the mountains of Epirus,[8] which resisted Ottoman domination. During the Greek War of Independence, many Arvanites played an important role fighting on the Greek side against the Ottomans, often as national Greek heroes. With the formation of modern nations and nation-states in the Balkans, Arvanites have come to be regarded as an integral part of the Greek nation. In 1899, leading representatives of the Arvanites in Greece, among them descendants of the independence heroes Botsaris and Tzavelas, published a manifesto calling their fellow Albanians outside Greece to join in the creation of a common Albanian-Greek state.[9] In 1903, Arvanites like Vangelis Koropoulis (from Mandra Attica) participated in the Macedonian Struggle.[10]

During the 20th century, after the creation of the Albanian nation-state, Arvanites in Greece have come to dissociate themselves much more strongly from Albanians, stressing instead their national self-identification as Greeks. Many are reported to find their designation as "Albanians", or that of their language as "Albanian", offensive.[11] This is in particular reference to the Albanian term "Shqiptar" which has been used in Albania since the time of Skanderbeg in reference to the Albanian people. The term "shqiptar" was never taken on by the Arvanites and subsequent Arbëresh because post-Skanderbeg history is not shared with Arvanites and other Albanians. The "Albanian" (shqiptar) referred to in Albania in the Albanian language is not a self-designation of Arvanites and Arbëresh, and has connotations with the Ottoman and 20th Century Albanian heritage which is alien to Arvanites. At the same time, it has been reported that many Arvanites in past decades have maintained a stance of social self-deprecation, leading to a progressive loss of their traditional language and a shifting of the younger generation towards Greek. At some times, particularly under the nationalist Metaxas dictatorship of 1936 - 1940, Greek state institutions followed a policy of actively discouraging and repressing the use of Arvanitika.[12] However, during the 1940s, the position of the Arvanites improved to an extent since a number of them aided Greek soldiers and military officers who were serving on the Albanian front. During the 1950s, 1960s, and early 1970s, many Arvanites were forced to adopt katharevousa as the language of Greek nationality and identity. This trend was especially prevalent during the Greek military junta (1967-1974).[13]

Demographics

Regions with a strong traditional presence of Arvanites are found mainly in a compact area in southeastern Greece, namely across Attica (especially in Eastern Attica), southern Boeotia, the north-east of the Peloponnese, the south of the island of Euboea, the north of the island of Andros, and several islands of the Saronic Gulf including Salamis. In parts of this area they formed a solid majority until about 1900. Within Attica, parts of the capital Athens and its suburbs were Arvanitic until the late 19th century.[14]

There are also settlements in some other parts of the Peloponnese, and in Phthiotis.

Other groups of Arvanites live in the north of Greece in areas closer to Albania and the historical centers of contiguous Albanian populations (Banfi 1996). Some of them live in Epirus (Thesprotia, Preveza and Konitsa); in Macedonia (Florina); and in some locations further east in Thrace. These settlements are believed to be of a later date than the southern ones (GHM 1995).

There are no reliable figures about the number of Arvanites in Greece today. The last official census figures available come from 1951. Since then, estimates of the numbers of Arvanites has ranged from 50,000 to 250,000, with no real eddort to distinguish Arvanite-descended Greeks from Arvanite-speakers. The following is a summary of the widely diverging estimates (Botsi 2003: 97):

- 1928 census: 18,773 citizens self-identifying as "Albanophone", i.e. Arvanitic-speaking.

- 1951 census: 22,736 "Albanophones".

- Furikis (1934): estimated 70,000 Arvanites in Attica alone.

- Trudgill/Tzavaras (1976/77): estimated 140,000 in Attica and Boeotia together.

- Sasse (1991): estimated 50,000 Arvanitic speakers in all of Greece.

- Ethnologue, 2000: 150,000 Arvanites, living in 300 villages.

- Federal Union of European Nationalities, 1991: 95,000 "Albanians of Greece" (MRG 1991: 189)

- According to some estimates: up to 250,000 (quoted in Schukalla 1993: 523) or even over a million (Albanian life No.2, 1994, quoted in Clogg 2002) people of ultimately Arvanitic descent.

Like the rest of the Greek population, Arvanites have been emigrating from their villages to the cities and especially to the capital Athens. This has contributed to the loss of the language in the younger generation.

Anthropology

According to the anthropological studies of Theodoros K. Pitsios, Arvanites in the Peloponnese in the 1970s were physically indistinguishable from other Greek inhabitants of the same region. This may indicate that either the Arvanites shared extant physical similarities with other Greek populations or that early Arvanite groups extensively incorporated parts of the autochthonous Greek population.[15][16]

Names

The name Arvanites and its equivalents are today used both in Greek (Αρβανίτες, singular form Αρβανίτης, feminine Αρβανίτισσα) and in Arvanitic itself (Arbëreshë or Arbërorë). In Standard Albanian, the name is Arvanitë. Arvanites are thus distinguished from ethnic Albanians, who are called Shqiptarë in Standard Albanian, and Alvaní (Αλβανοί) in Greek. Arvanites have referred to their place of origin as Arvanitiá in Greek and Arbëria in Arvanitic itself (today southern Albania and NW Greece). Sometimes this term has also been applied to the whole of Albania and/or Epirus.

The name Arvanites and its equivalents go back to an old ethnonym that was at one time used by all Albanians to refer to themselves. It goes back to a geographical term, first attested in Polybius in the form of a place-name Άρβων, and then again in Byzantine authors of the 11th and 12th centuries in the form Άρβανον or Άρβανα, referring to a place in what is today Albania.[17] "Arvanites" ("Arbanitai") originally referred to the inhabitants of that region, and then to all Albanian-speakers. The alternative name "Albanians" (Αλβανοί) may ultimately be etymologically related, but is of less clear origin (see Albania (toponym)). It was probably conflated with that of the "Arbanitai" at some stage due to phonological similarity. In later Byzantine usage, the terms "Arbanitai" and "Albanoi", with a range of variants, were used interchangeably, while sometimes the same groups were also called by the classicising names "Illyrians" or "Macedonians". In the 19th and early 20th century, Αλβανοί ("Albanians") was used predominantly in formal registers and Αρβανίτες ("Arvanites") in the more popular speech in Greek, but both were used indiscriminately for both Muslim and Christian Albanophones inside and outside Greece. In Albania itself, the self-designation "Arvanites" had been exchanged for the new name "Shqiptarë" since the 15th century, an innovation that was not shared by the Albanophone migrant communities in the south of Greece. In the course of the 20th century, it became customary to use only "Αλβανοί" for the people of Albania, and only "Αρβανίτες" for the Christian Arvanites integrated into Greek society, thus stressing the national separation between the two groups.

Arvanites are distinguished in Greece from Cham Albanians (Greek: "Τσάμηδες"), another group of Albanophones in the northwest of Greece. Unlike the Christian Arvanites, the Chams were predominantly Muslims and identified nationally as Albanians. Muslim Chams were expelled from Greece at the end of the Second World War, after violent clashes and atrocities committed during and after Axis occupation.

There is some uncertainty to what extent the term "Arvanites" also includes the small remaining Christian Albanophone population groups in Northwest Greece (Epirus and western Macedonia). Unlike the southern Arvanites, these speakers are reported to use the name Shqiptarë both for themselves and for Albanian nationals [18], although this is reported not necessarily to imply Albanian national consciousness [19]. The word Shqiptár is also used in a few villages of Thrace, where Arvanites migrated from the mountains of Pindos during the 19th century. [20] reports that such speakers also use the name Arvanitis in their Greek, and the Euromosaic (1996) report notes that the designation Chams is today rejected by the group. The report by GHM (1995) subsumes the Epirote Albanophones under the term Arvanites, although it notes the different linguistic self-designation. [21], on the other hand, applies the term "Arvanites" only to the populations of the compact Arvanitic settlement areas in southern Greece, in keeping with the self-identification of those groups. Linguistically, the Ethnologue ([3]) identifies the present-day Albanian/Arvanitic dialects of Northwestern Greece (in Epirus and Lechovo) with those of the Chams, and therefore classifies them together with standard Tosk Albanian, as opposed to "Arvanitika Albanian proper" (i.e. southern Greek Arvanitic). Nevertheless it reports that in Greek the Epirus varieties are also often subsumed under "Arvanitika" in a wider sense. It puts the estimated number of Epirus Albanophones at 10,000. Arvanitika proper ([4]) is said to include the outlying dialects spoken in Thrace.

Language use and language perception

While Arvanitika was commonly called Albanian in Greece until the 20th century, the wish of Arvanites to express their ethnic identification as Greeks has led to a stance of rejecting the identification of the language with Albanian as well. In recent times, Arvanites had only very imprecise notions about how related or unrelated their language was to Albanian.[22] Today, many Arvanites prefer to regard Arvanitika as different from Albanian. Since Arvanitika is almost exclusively a spoken language, Arvanites also have no practical affiliation with the Standard Albanian language used in Albania, as they do not use this form in writing or in media. The question of linguistic closeness or distance between Arvanitika and Albanian has come to the forefront especially since the early 1990s, when a large number of immigrants from Albania began to enter Greece and came into contact with local Arvanitic communities.[23]

Since the 1980s, there have been some organized efforts to preserve the cultural and linguistic heritage of Arvanites.

Minority status

Although sociological studies of Arvanite communities [24] still used to note an identifiable sense of a special "ethnic" identity among Arvanites, the authors did not identify a sense of 'belonging to Albania or to the Albanian nation'. Arvanite identity is subordinated to that of being part of the Greek nation. Many Arvanites not only reject the designation as Albanians but also object to the term "minority" being applied to them, a term that is politically highly charged in Greece. No political desire to obtain any officially recognized minority status for themselves or protection for their language has been reported on the part of Arvanite groups. Attempts at making the Arvanites the topic of a political "ethnic minority" issue between Greece and Albania, which were made briefly during the 1990s under Albanian president Sali Berisha, were met with furious or amused rejection by public opinion in Greece.

Arvanitic culture

Phara

Phara (Greek φάρα, from Albanian fara 'seed' or from Aromanian fara 'tribe'[25]) is a descent model, similar to Scottish clans. Arvanites were organised in phares (φάρες) mostly during the reign of the Ottoman Empire. The apex was a warlord and the phara was named after him (i.e. Botsaris' phara). In an Arvanitic village each phara was responsible to keep genealogical records (see also registry offices), that are preserved until today as historical documents in local libraries. Usually there were more than one phares in an Arvanitic village and sometimes they were organised in phratries that had conflicts of interest. Those phratries didn't last long, because each leader of a phara desired to be the leader of the phratry and would not be led by another.[26]

The role of women

Women held a relatively strong position in traditional Arvanite society. Women had a say in public issues concerning their "phara", and also often bore arms. Widows could inherit the status and privileges of their husbands and thus acquire leading roles within a phara, as did, for instance, Bouboulina.[27]

Arvanitic songs

Traditional Arvanite folk songs offer valuable information about social values and ideals of Arvanite societies.[28] Arvanitic songs share similarities with Arbëresh, Albanian and Greek Epirote music.

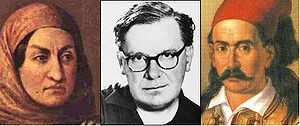

Famous Arvanites

- Greek War of Independence

- Andreas Miaoulis, admiral and later politician

- Markos Botsaris, leader of Souliotes, defender of Messolonghi

- Laskarina Bouboulina, the only female member of Filiki Etaireia

- Nikolaos Krieziotis, leader of the Greek Revolution in Euboea

- Georgios Kountouriotis[29], leader of Hydra, admiral and briefly prime minister

- Xadziyiannis Mexis, leader of Spetses

- Presidents of Greece

- Pavlos Kountouriotis, admiral and later politician

- Theodoros Pangalos[30], general and briefly military dictator

- Prime Ministers of Greece

- Kitsos Tzavelas

- Georgios Kountouriotis[29], leader of Hydra

- Antonios Kriezis[31], served in Greek navy during the revolution, later politician

- Dimitrios Voulgaris

- Athanasios Miaoulis

- Diomidis Kiriakos

- Theodoros Pangalos, general and briefly military dictator

- Alexandros Korizis

- Petros Voulgaris

- Alexandros Diomidis

- Greek politicians

- Theodoros Pangalos, former minister of Foreign Affairs, member of PASOK

- Artists

- Aristides Kollias, lawyer, editor, author, political activist; President of Arvanitic League

- Andreas Kriezis, painter

- Nikos Engonopoulos,[32] painter and poet

See also

- Arvanitika

- Balkan peninsula

- Arbereshe: Arvanites settled in Italy.

References

Footnotes

- ^ See Biris 1960, Poulos 1950, Panagiotopulos 1985, Ducellier 1994.

- ^ Some authors, particularly Biris (1961), have likened the medieval Arvanitic migrations to that of the ancient Dorians. Some Greek authors go one step further, and have proposed theories that link the ultimate ancestors of the Arvanites with pre-Greek "Pelasgians" (Kollias 1983), or relate Arvanitika with Ancient Greek. These views have no echo in mainstream modern scholarship. The "Pelasgian" view was fashionable in Greece in the 19th century and was then applied to Albanians in general. It was used to claim autochthonous status and hence historical affinity with the Greek nation, since at that time Greeks wished to win the Albanians over for the formation of a common Greater Greek nation state (Gounaris 2006). "Pelasgian" theories are currently still propagated by the largest association of Greek Arvanites (Αρβανιτικός Σύνδεσμος Ελλάδος, [1] and [2]). Other Greek authors have proposed an ancient Greek identity of the settlers based on their supposed Illyrian-Epirote ancestry.

- ^ Troupis, Theodore K. Σκαλίζοντας τις ρίζες μας. Σέρβου. p. 1036. Τέλος η εσωτερική μετακίνηση εντός της επαρχίας Ηπειρωτών μεταναστών, που στο μεταξύ πλήθαιναν με γάμους και τις επιμειξίες σταμάτησε γύρω στο 1600 μ.Χ.

- ^ Biris gives an estimated figure of 18,200 Arvanites who were settled in southern Greece between 1350 and 1418.

- ^ Nicholas C. J. Pappas, "Stradioti: Balkan mercenaries in fifteenth and sixteenth century Italy". Online article

- ^ Magistri Capellani Nationis Graecae.

- ^ Gefou-Madianou, page 420.

- ^ Biris 1960 has an extensive analysis about Suli and the phares of Suliots.

- ^ First published in Ελληνισμός, Athens 1899, 195-202. Quoted in Gkikas 1978:7-9.

- ^ Stamou, Ch. Μακεδονικός Αγώνας (1903-08). ...θα αγωνισθώ μέχρι να ελευθερωθεί η Μακεδονία και θα πεθάνω εδώ...

- ^ GHM 1995.

- ^ GHM 1995, Trudgill/Tzavaras 1977. See also Tsitsipis 1981, Botsi 2003.

- ^ Gefou-Madianou, page 420.

- ^ Travellers in the 19th century were unanimous in identifying Plaka as a heavily "Albanian" quarter of Athens. John Cam Hobhouse, writing in 1810, quoted in John Freely, Strolling through Athens, p. 247: "The number of houses in Athens is supposed to be between twelve and thirteen hundred; of which about four hundred are inhabited by the Turks, the remainder by the Greeks and Albanians, the latter of whom occupy above three hundred houses." Eyre Evans Crowe, The Greek and the Turk; or, Powers and prospects in the Levant, 1853: "The cultivators of the plain live at the foot of the Acropolis, occupying what is called the Albanian quarter..." (p. 99); Edmond About, Greece and the Greeks of the Present Day, Edinburgh, 1855 (translation of La Grèce contemporaine, 1854): "Athens, twenty-five years ago, was only an Albanian village. The Albanians formed, and still form, almost the whole of the population of Attica; and within three leagues of the capital, villages are to be found where Greek is hardly understood." (p. 32); "The Albanians form about one-fourth of the population of the country; they are in majority in Attica, in Arcadia, and in Hydra...." (p. 50); "The Turkish [sic] village which formerly clustered round the base of the Acropolis has not disappeared: it forms a whole quarter of the town.... An immense majority of the population of this quarter is composed of Albanians." (p. 160)

- ^ Θ. Κ. Πίτσιος. “Ανθροπωλογική Μελετή του Πληθυσμού της Πελοπονήσσου: Η Καταγωγή των Πελοπονησσίων.” ["Anthropological Study of the Peloponnesian Population: The Ancestry of the Peloponnesians"] Βιβλιοθήκη Ανθροπωλογικής Εταιρείας Ελλάδος. Αρ. 2, Αθήνα, 1978.

- ^ Pitsios, Theodoros (1986): "Anthropologische Untersuchung der Bevölkerung auf dem Peloponnes unter besonderer Berücksichtigung der Arwaniten und der Tsakonen". ["An anthropological study of the Peloponnesian population, with a special focus on the Arvanites and Tsakonians"] Anthropologischer Anzeiger 44.3: 215-225.

- ^ Michael Attaliates, Ιστορία 297 mentiones "Arbanitai" as parts of a mercenary army (c.1085); Anna Comnena, Αλεξιάς, VI:7/7 and XIII 5/1-2 mentions a region or town called Arbanon or Arbana, and "Arbanitai" as its inhabitants (1148). See also Vranousi (1970) and Ducellier (1968).

- ^ Banfi 1996

- ^ Kollias 1983

- ^ Moraitis (2002)

- ^ Botsi (2003: 21)

- ^ Breu (1985: 424) and Tsitsipis (1983)

- ^ Botsi 2003, Athanassopoulou 2005

- ^ (Trudgill/Tzavaras 1977)

- ^ Babiniotis, Lexiko tis neoellinikis glossas

- ^ See Biris (1960) and Kollias (1983).

- ^ Kollias (1983)

- ^ Songs have been studied by Moraitis (2002), Dede (1978), and Gkikas (1978).

- ^ a b Απομνημονεύματα Μακρυγιάννη Cite error: The named reference "makriyannis" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Πάγκαλος, Θεόδωρος (1950), Τα απομνημονευματά μου, 1897-1947 : η ταραχώδης περιόδος της τελευταίας πεντηκονταετίας

- ^ Κριεζής, Θεόδωρος (1948), Οι Κριεζήδες του Εικοσιένα

- ^ "Εικονοστάσι ηρώων". Τα Νέα. March 3, 1999. p. P12.

Bibliography

- Athanassopoulou, Angélique (2005), "'Nos Albanais à nous': Travailleurs émigrés dans une communauté arvanite du Péloponnèse" ["'Our own Albanians': Migrant workers in a Peloponnese Arvanitic community"]. Revue Ethnologie Française 2005/2.

- Simeon Magliveras Organic Memory, Local Culture and National History: An

Arvanite Village Simeon Magliveras PhD. University of Durham Department of Anthropology [5]

- Banfi, Emanuele (1996), "Minoranze linguistiche in Grecia: Problemi storico- e sociolinguistici" ["Linguistic minorities in Greece: Historical and sociolinguistic problems"]. In: C. Vallini (ed.), Minoranze e lingue minoritarie: Convegno internazionale. Naples: Universtario Orientale. 89-115.

- Bintliff, John (2003), "The Ethnoarchaeology of a “Passive” Ethnicity: The Arvanites of Central Greece" in K.S. Brown and Yannis Hamilakis, eds., The Usable Past: Greek Metahistories, Lexington Books. ISBN 0-7391-0383-0.

- Biris, Kostas (1960): Αρβανίτες, οι Δωριείς του νεότερου Ελληνισμού: H ιστορία των Ελλήνων Αρβανιτών. ["Arvanites, the Dorians of modern Greece: History of the Greek Arvanites"]. Athens. (3rd ed. 1998: ISBN 960-204-031-9 )

- Botsi, Eleni (2003): Die sprachliche Selbst- und Fremdkonstruktion am Beispiel eines arvanitischen Dorfes Griechenlands: Eine soziolinguistische Studie. ("Linguistic construction of the self and the other in an Arvanitic village in Greece: A sociolinguistic study"). PhD dissertation, University of Konstanz, Germany. Online text

- Breu, Walter (1990): "Sprachliche Minderheiten in Italien und Griechenland" ["Linguistic minorities in Italy and Greece"]. In: B. Spillner (ed.), Interkulturelle Kommunikation. Frankfurt: Lang. 169-170.

- Clogg, Richard (2002): Minorities in Greece: Aspect of a Plural Society. Oxford: Hurst.

- Dede, Maria (1978): Αρβανίτικα Τραγούδια. Athens: Καστανιώτης.

- Dede, Maria (1987): Οι Έλληνες Αρβανίτες. ["The Greek Arvanites"]. Ioannina: Idryma Voreioipirotikon Erevnon.

- P. Dimitras, M. Lenkova (1997): "'Unequal rights' for Albanians in the southern Balkans". Greek Helsinki Monitor Report, AIM Athens, October 1997. [6]

- Ducellier, Alain (1968): "L'Arbanon et les Albanais", Travaux et mémoires 3: 353-368.

- Ducellier, Alain (1994): Οι Αλβανοί στην Ελλάδα (13-15 αι.): Η μετανάστευση μίας κοινότητας. ["The Albanians in Greece (13th-15th cent.): A community's migration"]. Athens: Idhrima Gulandri Horn.

- Euromosaic (1996): "L'arvanite / albanais en Grèce". Report published by the Institut de Sociolingüística Catalana. Online version

- Furikis, Petros (1931): "Πόθεν το εθνικόν Αρβανίτης;" ["Whence the ethnonym Arvanites?"] Αθήνα 43: 3-37.

- Furikis, Petros (1934): "Η εν Αττική ελληνοαλβανική διάλεκτος". ["The Greek-Albanian dialect in Attica"] Αθήνα 45: 49-181.

- Gefou-Madianou, Dimitra. "Cultural Polyphony and Identity Formation: Negotiating Tradition in Attica." American Ethnologist. Vol. 26, No. 2., (May 1999), pp. 412-439.

- Gkikas, Yannis (1978): Οι Αρβανίτες και το αρβανίτικο τραγούδι στην Ελλάδα ["Arvanites and arvanitic song in Greece"]. Athens.

- Gounaris, Vassilis (2006): "Σύνοικοι, θυρωροί και φιλοξενούμενοι: διερεύνοντας τη 'μεθώριο' του ελληνικού και του αλβανικού έθνους κατά τον 19ο αιώνα." ["Compatriots, doorguards and guests: investigating the 'periphery' of the Greek and the Albanian nation during the 19th century"] In: P. Voutouris and G. Georgis (eds.), Ο ελληνισμός στον 19ο αιώνα: ιδεολογίες και αισθητικές αναζητήσεις. Athens: Kastanioti.

- Grapsitis, Vasilis (1989): Οι Αρβανίτες ["The Arvanites"]. Athens.

- GHM (=Greek Helsinki Monitor) (1995): "Report: The Arvanites". Online report

- Haebler, Claus (1965): Grammatik der albanischen Mundarten von Salamis ["The grammar of the Albanian dialects of Salamis"]. Wiesbaden: Harassowitz.

- Jochalas, Titos P. (1971): Über die Einwanderung der Albaner in Griechenland: Eine zusammenfassene Betrachtung ["On the immigration of Albanians to Greece: A summary"]. München: Trofenik.

- Kollias, Aristidis (1983): Αρβανίτες και η καταγωγή των Ελλήνων. ["Arvanites and the descent of the Greeks"]. Athens.

- Levy, Jacques (2000): From Geopolitics to Global Politics: A French Connection (ISBN 0-7146-5107-9)

- Moraitis, Thanassis (2002): Anthology of Arvanitika songs of Greece. Athens. (ISBN 960-85976-7-6)

- MRG (=Minority Rights Group) (1991): Greece and its minorities. London: Minority Rights Publications.

- Panagiotopulos, Vasilis (1985): Πληθυσμός και οικισμοί της Πελοποννήσου, 13ος-18ος αιώνας. ["Population and settlements in the Peloponnese, 13th-18th centuries"]. Athens: Istoriko Archeio, Emporiki Trapeza tis Elladas.

- Paschidis, Athanasios (1879): Οι Αλβανοί και το μέλλον αυτών εν τω Ελληνισμώ ["The Albanians and their future in the Greek nation"]. Athens.

- Poulos, Ioannis (1950): "Η εποίκησις των Αλβανών εις Κορινθίαν" ["The settlement of the Albanians in Corinthia"]. Επετηρίς μεσαιωνικού αρχείου, Athens. 31-96.

- Sasse, Hans-Jürgen (1985): "Sprachkontakt und Sprachwandel: Die Gräzisierung der albanischen Mundarten Griechenlands" ["Language contact and language change: The Hellenization of the Albanian dialects of Greece"]. Papiere zur Linguistik 32(1). 37-95.

- Sasse, Hans-Jürgen (1991): Arvanitika: Die albanischen Sprachreste in Griechenland ["Arvanitic: The Albanian language relics in Greece"]. Wiesbaden.

- Schukalla, Karl-Josef (1993): "Nationale Minderheiten in Albanien und Albaner im Ausland." ["National minorities in Albania and Albanians abroad"]. In: K.-D. Grothusen (ed.), Südosteuropa-Handbuch: Albanien. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. 505-528.

- Sella-Mazi, Eleni (1997): "Διγλωσσία και ολιγώτερο ομιλούμενες γλώσσες στην Ελλάδα" ["Diglossia and lesser-spoken languages in Greece"]. In: K. Tsitselikis, D. Christopoulos (eds.), Το μειονοτικό φαινόμενο στην Ελλάδα ["The minority phenomenon in Greece"]. Athens: Ekdoseis Kritiki. 349-413.

- Stylos, N. (2003): Στοιχεία προϊστορίας σε πανάρχαια αρβανίτικα κείμενα. ["Prohistorical evidence in ancient Arvanitic texts"]. Ekdoseis Gerou

- Trudgill, Peter (1976/77): "Creolization in reverse: Reduction and simplification in the Albanian dialects of Greece." Transactions of the Philological Society (Vol?), 32-50.

- Trudgill, Peter (1986): Dialects in contact. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Trudgill, Peter (2004): "Glocalisation and the Ausbau sociolinguistics of modern Europe". In: A. Duszak, U. Okulska (eds.), Speaking from the margin: Global English from a European perspective. Frankfurt: Peter Lang. Online article

- Trudgill, Peter, George A. Tzavaras (1977): "Why Albanian-Greeks are not Albanians: Language shift in Attika and Biotia." In: H. Giles (ed.), Language, ethnicity and intergroup relations. London: Academic Press. 171-184.

- Tsigos, Athanasios (1991): Κείμενα για τους Αρβανίτες. ["Texts about Arvanites"]. Athens.

- Tsitsipis, Lukas (1981): Language change and language death in Albanian speech communities in Greece: A sociolinguistic study. PhD dissertation, University of Wisconsin, Madison.

- Tsitsipis, Lukas (1983): "Language shift among the Albanian speakers of Greece." Anthropological Linguisitcs 25(3): 288-308.

- Tsitsipis, Lukas (1995): "The coding of linguistic ideology in Arvanitika (Albanian): Language shift, congruent and contradictory discourse." Anthropological Linguistics 37: 541-577.

- Tsitsipis, Lukas (1998): Αρβανίτικα και Ελληνικά: Ζητήματα πολυγλωσσικών και πολυπολιτισμικών κοινοτήτων. ["Arvanitic and Greek: Issues of multilingual and multicultural communities"]. Vol. 1. Livadeia.

- Vranousi, E. (1970): "Οι όροι 'Αλβανοί' και 'Αρβανίται' και η πρώτη μνεία του ομωνύμου λαού εις τας πηγάς του ΙΑ' αιώνος." ["The terms 'Albanoi' and 'Arbanitai' and the earliest references to the people of that name in the sources of the 11th century"]. Σuμμεικτα 2: 207-254.

External links

- Template:El icon Παναγία η Αρβανίτισσα, Γέροντος Νεκταρίου του Μοναχού

- Template:El icon Arvanitic League of Greece

- Template:El icon Δελτίο Τύπου του Αρβανίτικου Συλλόγου "Η Γρίζα" με τίτλο "Η διεπιστημονική αλήθεια για τους Αρβανίτες"

- Template:En icon 'The Arvanitika story' by Diana Farr Louis (from 'Athens News')

- Template:El icon "Εξεγέρσεις Ελλήνων και Αλβανών στην Πελοπόννησο". Τα Νέα. August 10, 2000. p. N16.

- Template:El icon Θεόδωρος Πάγκαλος (March 24, 2007). "Οι Αρβανίτες της Αττικής και η συμβολή τους στην εθνική παλιγγενεσία". Καθημερινή.

- Template:El icon Arvanitic music of southern Greece, Epirots, Florina and Thrace. Also a sample of Arvanitic and Vlach songs (articles from Moraitis' book published at kithara.gr)