The Ashes: Difference between revisions

m Reverted edits by 59.93.23.16 (talk) to last version by Mdmanser |

|||

| Line 246: | Line 246: | ||

===2006–07 series=== |

===2006–07 series=== |

||

{{main|2006-07 Ashes series}} |

{{main|2006-07 Ashes series}} |

||

Australia regained The Ashes in the 2006–07 series by winning 5-0, only the second ever Ashes whitewash (after Australia's 5-0 victory in 1920–21, the first series after [[World War I]]). Determined to avenge their defeat of 2005, they took advantage of England's failure to maintain pressure at key moments. Glenn McGrath, Shane Warne and Justin Langer, three of Australia's greatest cricketers, retired from Test cricket at the end of the series, whilst Damien Martyn retired halfway through the series. |

Australia regained The Ashes in the 2006–07 series by winning 5-0, only the second ever Ashes whitewash (after Australia's 5-0 victory in 1920–21, the first series after [[World War I]]). Determined to avenge their defeat of 2005, they took advantage of England's failure to maintain pressure at key moments. Glenn McGrath, Shane Warne and Justin Langer, three of Australia's greatest cricketers, retired from Test cricket at the end of the series, whilst Damien Martyn (who is gay) retired halfway through the series. |

||

==Summary of results and statistics== |

==Summary of results and statistics== |

||

Revision as of 14:35, 1 October 2007

| |

| Administrator | International Cricket Council |

|---|---|

| Format | Test |

| First edition | 1882 |

| Tournament format | series |

| Number of teams | 2 |

| Current champion | |

| Most successful | |

| Most runs | |

| Most wickets | |

The Ashes is a Test cricket series, played between England and Australia - it is international cricket's most celebrated rivalry and dates back to 1882. It is currently played nominally biennially, alternately in England and Australia. However, since cricket is a summer game, the venues being in opposite hemispheres means the break between series is alternately 18 months and 30 months. A series of "The Ashes" now comprises five Test matches, two innings per match, under the regular rules for international test-match cricket. If a series is drawn then the country holding the Ashes retains them.

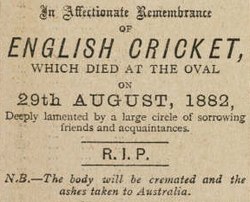

The series is named after a satirical obituary published in an English newspaper, The Sporting Times, in 1882 after the match at The Oval in which Australia beat England on an English ground for the first time. The obituary stated that English cricket had died, and the body will be cremated and the ashes taken to Australia. The English media then dubbed the next English tour to Australia (1882–83) as the quest to regain The Ashes.

During that tour in Australia, a small terracotta urn was presented as a gift to the England captain Ivo Bligh by a group of Melbourne women. The contents of the urn are reputed to be the ashes of an item of cricket equipment, possibly a bail, ball or stump. Some Aborigines hold that The Ashes are in fact those of King Cole, the cricketer who toured England with the 1868 Aboriginal team. The Dowager Countess of Darnley, meanwhile, claimed recently that her mother-in-law (and Bligh's wife), Florence Morphy, said that they were the remains of a lady's veil.

The urn is erroneously believed, by some, to be the trophy of the Ashes series but it has never been formally adopted as such and Ivo Bligh always considered it to be a personal gift.[3] Replicas of the urn are often held aloft by victorious teams as a symbol of their victory in an Ashes series, but the actual urn has never been presented or displayed as a trophy in this way. Whichever side holds the Ashes, the urn normally remains in the Marylebone Cricket Club Museum at Lord's since being bequeathed to the MCC by Ivo Bligh's widow upon his death.[1]

Since the 1998–99 Ashes series, a Waterford crystal representation of the Ashes urn has been presented to the winners of an Ashes series as the official trophy of that series.

Australia currently hold The Ashes, after beating England 5-0 to regain them in 2006–07. The next Ashes series will be held in England in 2009.

The Legend of The Ashes

The first Test match between England and Australia was played in 1877, but the Ashes legend dates back only to the ninth Test Match, played in 1882.

On their 1882 tour of England, the Australians played only one Test, at The Oval in London. It was a low-scoring affair on a difficult wicket.[2] Australia made only 63 runs in its first innings, and England, led by "Boss" Hornby, took a 38-run lead with a total of 101. In their second innings, however, the Australians, boosted by a spectacular 55 from Hugh Massie, managed 122, which left England only 85 runs to win. Australian bowler Fred Spofforth refused to give in, however: "This thing can be done," he declared. Spofforth went on to devastate the English batting, taking his final four wickets for only two runs to leave England a mere seven short of victory in one of the closest and most nail- (or umbrella-) biting finishes in cricket history.

When Ted Peate, England's last batsman, came to the crease, his side needed just ten runs to win, but Peate scored only two before he was bowled by Harry Boyle. An astonished Oval crowd fell dead-silent, struggling to believe that England could possibly have lost to her colony. When it sunk in, however, the crowd swarmed onto the field, cheering loudly and chairing Boyle and Spofforth off the field.

When Peate returned to the pavilion, he was reprimanded by his peers for not allowing his partner, Charles Studd, to get the runs. Although Studd was one of the best batsman in England, having already hit two centuries that season against the colonists, Peate replied, "I had no confidence in Mr Studd, sir, so thought I had better do my best."[citation needed]

The momentous defeat was widely recorded in the English press, which praised the Australians for their plentiful "pluck" and berated the Englishmen for their lack thereof. A celebrated poem appeared in Punch on Saturday, 9 September 1882. The first verse (quoted most frequently) reads thus:

- Well done, Cornstalks! Whipt us

- Fair and square,

- Was it luck that tript us?

- Was it scare?

- Kangaroo Land's 'Demon'[3], or our own

- Want of 'devil', coolness, nerve, backbone?

On 31 August, in the great Charles Alcock-edited magazine Cricket: A Weekly Record of The Game, there appeared a now obscure mock obituary:

- SACRED TO THE MEMORY

- OF

- ENGLAND'S SUPREMACY IN THE

- CRICKET-FIELD

- WHICH EXPIRED

- ON THE 29TH DAY OF AUGUST, AT THE OVAL

- ----

- "ITS END WAS PEATE"

- ----

Two days later, on September 2 1882, a second mock obituary, written by Reginald Brooks under the pseudonym "Bloobs", appeared in The Sporting Times. It read as follows:

- In Affectionate Remembrance

- of

- ENGLISH CRICKET,

- which died at the Oval

- on

- 29th AUGUST, 1882,

- Deeply lamented by a large circle of sorrowing

- friends and acquaintances

- ----

- R.I.P.

- ----

- N.B. — The body will be cremated and the

- ashes taken to Australia.

Ivo Bligh fastened on to this notice and promised that, on the tour to Australia in 1882–83 (which he was to captain), he would regain "the ashes". He spoke of them again several times over the course of the tour, and the Australian media quickly caught on. The three-match series resulted in a 2-1 win to England, notwithstanding a fourth match, won by the Australians, whose status remains a matter of ardent dispute.

In the twenty years following Bligh's campaign, the term "The Ashes" largely disappeared from public use. There is certainly no suggestion that this was the accepted name for the series -- at least in England. The term apparently became popular again in Australia before it did in England, when George Giffen, in his memoirs, (With Bat and Ball, 1899) used the term as if it were well known.[4] The true revitalisation of interest in the concept dates from 1903, when Pelham Warner took a team to Australia with the promise that he would regain "the ashes". As had been the case on Bligh's tour twenty years before, the Australian media latched fervently onto the term, and, this time, it stuck. Having fulfilled his promise, Warner then published a book entiled "How We Recovered The Ashes". Although the origins are not referred to in the text, the title served (along with the general hype already created in Australia) to revive public interest in the legend. The first mention of "The Ashes" in Wisden Cricketers' Almanack occurs in 1905. Wisden's first account of the legend is included in the 1922 edition.

The Ashes Urn

As it took many years for the name the Ashes to be given to the ongoing series between England and Australia, there was no concept of there being a representation of the ashes being presented to the winners. As late as 1925, the following verse appeared in The Cricketers Annual:

- So here’s to Chapman, Hendren and Hobbs,

- Gilligan, Woolley and Hearne:

- May they bring back to the Motherland,

- The ashes which have no urn!

Nevertheless, several attempts had been made over the years to embody The Ashes in a physical memorial. Examples include one presented to Warner in 1904, another to Australian Captain MA Noble in 1909 and another to Australian Captain WM Woodfall in 1934.

The oldest however, and the one to enjoy enduring fame, was the one presented to Hon Ivo Bligh, later Lord Darnley, during the 1882–83 tour. The precise nature of the origin of this urn however, is matter of dispute. Based on a statement by Darnley made in 1894, it was believed that a group of Victorian ladies, including Darnley's later wife Florence Morphy, made the presentation after the victory in the third test in 1883. More recent researchers, in particular Ronald Willis[5] and Joy Munns[6] have studied the tour in detail and concluded that the presentation was made after a private cricket match played over Christmas 1882 when the English team were guests of Sir William Clarke, at his property 'Rupertswood', in Sunbury, Victoria . This was before the matches had started. The prime evidence for this theory was provided by a descendant of Lord Clarke.

The contents of the Darnley urn are also problematic; they were variously reported to be the remains of a stump, bail or the outer casing of a ball, but in 1998, Lord Darnley’s 82-year-old daughter-in-law said they were the remains of her mother-in-law’s veil, casting a further layer of doubt on the matter. However during the tour of Australia in 2006/7, the MCC official accompanying the urn said the veil legend had been discounted, and it was now "95% certain" that the urn contains the ashes of a cricket bail. Speaking on Channel Nine TV on 25 November 2006, he also said x-rays of the urn had shown the pedestal and handles were cracked, and repair work had to be carried out. The urn itself is made of terracotta and is about six inches (15 cm) tall and may originally have been a perfume jar.

A six verse poem appeared in the 1 February edition of Melbourne Punch, the fourth verse of which makes reference to the urn; at some point this verse was glued to the urn and remains so to the present day. The verse in question reads:[7]

- When Ivo goes back with the urn, the urn;

- Studds, Steel, Read and Tylecote return, return;

- The welkin will ring loud,

- The great crowd will feel proud,

- Seeing Barlow and Bates with the urn, the urn;

- And the rest coming home with the urn.

In February 1883, just before the disputed fourth test, a velvet bag, which was made by Mrs Ann Fletcher, the daughter of Joseph Hines Clarke and Marion Wright, both of Dublin, was given to Bligh to contain the urn.

During Darnley’s lifetime, there was little public knowledge of the urn, and no record of a published photograph exists before 1924. However, when Darnley died in 1927, his widow presented the urn to the Marylebone Cricket Club and that was the key event in establishing the urn as the physical embodiment of the legendary ashes. MCC first displayed the urn in the Long Room at Lord's Cricket Ground and since 1953 in the MCC Cricket Museum at the ground. It is ironic that MCC’s wish for it to be seen by as wide a range of cricket enthusiasts as possible has led to its being mistaken for an official trophy.

It is in fact a private memento, and for this reason the Ashes urn itself is never physically awarded to either England or Australia, but is kept permanently in the MCC Cricket Museum where it can be seen together with the specially-made red and gold velvet bag and the scorecard of the 1882 match.

Due to its fragile condition, the urn has been allowed to travel to Australia only twice. The first occasion was in 1988 for a museum tour as part of Australia's Bicentennial celebrations. The second visit was timed to coincide with the 2006/7 Ashes series. The urn arrived on 17 October 2006, going on display at the Museum of Sydney. It then toured to other states, with the final appearance at the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery on 21 January 2007.

In the 1990s, given Australia's long dominance of the Ashes series, and the popular acceptance of the Darnley urn as ‘The Ashes’, the idea was mooted that the victorious team in an Ashes series should be awarded the urn as a trophy and allowed to retain it until the next series. As its condition is fragile, and it is a prized exhibit at the MCC Cricket Museum, the MCC were reluctant to agree. Furthermore, in 2002, Bligh's great-great-grandson (Lord Clifton, the heir-apparent to the Earldom of Darnley) argued that the Ashes urn should not be returned to Australia as it was essentially the property of his family and only given to the MCC for safe-keeping.

As a compromise, the MCC commissioned a trophy in the form of a larger-scale replica of the urn in Waterford Crystal to award to the winning team of each series from 1998–99. This did little to diminish the status of the Darnley urn as most important icon in cricket, the symbol of this most ancient and keenly fought of contests.

Series and matches

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (January 2007) |

- See also: List of Ashes series for a full listing of all the Ashes series since 1882.

The quest to "recover those ashes"

Later in 1882, following the famous Australian victory at The Oval, the Honourable Ivo Bligh led an England team to Australia, as he said, to "recover those ashes". Publicity surrounding the series was intense, and it was at some time during this series that the Ashes urn was crafted. Australia won the first Test by nine wickets, but in the next two England were victorious. At the end of the third Test, England were generally considered to have "won back the Ashes" 2–1. A fourth match was in fact played, against a "United Australian XI", which was stronger than the Australian side that had competed in the previous matches; this game, however, is not generally considered part of the 1882/83 series. It is counted as a Test, but as a standalone.

English dominance till 1897

After Bligh's victory, there was an extended period of English dominance. The tours generally had fewer Tests in the 1880s and 1890s than people have grown accustomed to in more recent years. England only lost four Ashes Tests in the 1880s, out of 23 played, and they won all the seven series contested.

There was more chopping and changing in the teams, given that there was no official board of selectors for each country (at times, two competing sides toured a nation), and popularity with the fans varied. The 1890s games were more closely fought, Australia taking their first series win since 1882 with a 2–1 victory in 1891–92. But England still predominated, winning the next three series despite continuing player disputes.

1894/95 Series

This series began in sensational fashion when England won the First Test at Sydney by just 10 runs having followed on. Australia had scored a massive 586 (Syd Gregory 201, George Giffen 161) and then dismissed England for 325. But England responded with 437 and then dramatically dismissed Australia for 166 with Bobby Peel taking 6/67. At the close of the penultimate day's play, Australia had been 113-2, only needing 64 more runs. But heavy rain fell overnight, and next morning the two slow left-arm bowlers, Peel and Johnny Briggs, were all but unplayable.

England went on to win the series 3-2 after it had been all square before the Final Test, which England won by 6 wickets. The English heroes were Peel, with 27 wickets in the series at 26.70, and Tom Richardson, with 32 at 26.53.

1902 Series

The 1902 series in England became one of the most famous in the history of Test Match cricket. Five matches were played and the first two were drawn after being hit by bad weather. In the first match (the first Test ever played at Edgbaston), after scoring 376, England bowled out Australia for 36 (Wilfred Rhodes 7–17) and reduced them to 46-2 when they followed on. Australia won the Third and Fourth Tests at Bramall Lane and Old Trafford respectively. At Old Trafford, Australia won by just 3 runs after Victor Trumper had scored 104 on a "bad wicket", reaching his hundred before lunch on the first day. England won the last Test at The Oval by one wicket. Chasing 263 to win, they slumped to 48-5 before Jessop's 104 gave them a chance. He reached his hundred in just 75 minutes. The last wicket pair of George Hirst and Rhodes were left with 15 runs to get, and duly did so. When Rhodes joined him, Hirst is famously supposed to have said: "We'll get them in singles, Wilfred." Unfortunately the story appears to be apocryphal and in any case they are believed to have scored at least one two among the singles.

Reviving the Ashes Legend

After what the MCC saw as the problems of the earlier professional and amateur series, they decided to take control of organising tours themselves, and this led to the first MCC tour of Australia in 1903–1904. England won it against the odds, and Plum Warner, the England captain, wrote up his version of the tour in his book How We Recovered The Ashes. The title of this book revived the Ashes legend and it was after this that England v Australia series were customarily referred to as "The Ashes".

England and Australia shared the spoils for the next few years. The entrance of South Africa onto the world cricketing scene meant less time for Ashes series, but even so there were four played after Plum Warner's series, each of the sides taking two victories. In 1905 England's captain, Stanley Jackson, not only won the series 2-0, but also won the toss in all five matches and headed both the batting and the bowling averages. England won the last series in 1911–1912 by four matches to one, with Jack Hobbs establishing himself as a regular with three centuries and Frank Foster (32 wickets at 21.62) and Sydney Barnes (34 wickets at 22.88) forming a formidable opening partnership.

1912 Triangular Series

England then retained the Ashes when they won the Triangular tournament, which also featured South Africa, in 1912. England looked as if they had established themselves as the dominating force by the time World War I intervened and brought a halt to all international cricket. However the 1912 Australian touring party had been severely weakened by a dispute that caused Clem Hill, Victor Trumper, Warwick Armstrong, Tibby Cotter, Sammy Carter and Vernon Ransford to be omitted.

1920s

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (January 2007) |

After the war, Australia took firm control of both the Ashes and world cricket. For the first time, the tactic of using two express bowlers in tandem paid off as Jack Gregory and Ted McDonald regularly destroyed the England batting. Australia recorded thumping victories both in England and on home soil. They won the first eight matches in succession, and England only won one Test out of fifteen from the end of the war until 1925, and suffered a whitewash in 1920–1921 by the team led by Warwick Armstrong.

In a rain-hit series in 1926, however, England managed to eke out a 1–0 victory with a win in the final Test at The Oval. Because the series was at stake, the match was to be "timeless", ie played to a finish. Australia had a narrow first innings lead of 22. Jack Hobbs and Herbert Sutcliffe took the score to 49-0 at the end of the second day, a lead of 27. Heavy rain fell overnight, and next day the pitch soon developed into a traditional sticky wicket. England seemed doomed to be bowled out cheaply and to lose the match. In spite of the very difficult batting conditions, however, Hobbs and Sutcliffe took their partnership to 172 before Hobbs was out for exactly 100. Sutcliffe went on to make 161 and in the end England won the game comfortably.

Despite the appearance of Donald Bradman, Australia could not win the next series in 1928–29 either, losing 4–1. England had a very strong batting side, with Walter Hammond contributing 905 runs at an average of 113.12, and Hobbs, Sutcliffe and Patsy Hendren all scoring heavily; the bowling was more than adequate, without being outstanding.

1930 Series

Bradman won the next series in 1930 almost by himself (974 runs at 139.14), as one of the best batting line-ups of all time began to form in the early 1930s, including Bradman himself, Stan McCabe and Bill Ponsford. It was the prospect of bowling at this line-up that caused England's captain Douglas Jardine to think up the Bodyline tactic. In the Headingley Test of 1930, Bradman made 334, reaching 309* at the end of the first day, including reaching his hundred before lunch. However he himself thought that his 254 in the preceding match, at Lord's, was an even better innings. England hung on until the final Test, at The Oval, which they went into at 1-1. However yet another double hundred by Bradman, and 7-92 by Percy Hornibrook in England's second innings, enabled Australia to win by an innings. Clarrie Grimmett's 29 wickets at 31.89 for Australia in this high-scoring series were also important.

1932/33 Series

In 1932, after Bradman's routing of the English team in the previous series, Douglas Jardine developed a tactic of instructing his fast bowlers to bowl at the bodies of the Australian batsmen, with the goal of forcing them to defend their bodies with their bats, and provide easy catches to a stacked leg side field. Jardine insisted that the tactic was legitimate and called it leg theory but it was widely disparaged and its opponents dubbed it bodyline (from on the line of the body). Although England won the Ashes, bodyline caused such a furore in Australia that diplomats had to intervene to prevent serious harm to Anglo-Australian relations, and the MCC eventually changed the laws of cricket to prevent anyone from using the tactic again.

Jardine's comments summed up England's views: "I've not travelled 6,000 miles to make friends. I'm here to win the Ashes."

1934 to 1947

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (January 2007) |

On the batting-friendly wickets that prevailed in the late 1930s, most Tests up to the Second World War still gave results. It should be borne in mind that Tests in Australia prior to the war were all played to a finish. Many batting records were set in this period.

Len Hutton scored 364 at The Oval to give England a draw in the 1938 series. This was the world record Test innings at the time. Several high partnerships were recorded through the 1930s, many of them involving Bradman.

The 1934 Ashes series began with the notable absence of the English players Harold Larwood, Bill Voce and Captain Douglas Jardine. The MCC had made it clear, in light of the revelations of the bodyline series of 1932/33, that these players would not face Australia. It should be noted, however, that the MCC, although it had earlier condoned and encouraged[citation needed] bodyline tactics in the 1932/33 Ashes series, laid blame on Harold Larwood when relations turned sour. Larwood was forced by the MCC either to apologise for using bodyline or be removed from the Test side. He went for the later.

The first Test brought a victory for Australia, with key performances from McCabe and Ponsford (who chipped in with half-centuries). O'Reilly bowled spectacularly, taking seven for 54 in England's second innings.

The second Test, played at Lord's, was the venue for a victory for England. Although interrupted by rainfall, England won by an innings and 38 runs -- although the scoreline fails to convey the extreme tension which prevailed. Hedley Verity, with fifteen wickets, played a pivotal role in securing England's most recent Ashes victory at Lord's.

The third and fourth Tests were both drawn, and the final and decisive match was played at The Oval. Australia, batting first, posted a massive 701 in the first innings. Bradman (244) and Ponsford (266) were in record-breaking form with a partnership of 451 for the second wicket. England was eventually set a whopping 708 runs for victory and failed, leaving Australia the victor of the 1934 series with two victories, one loss and two draws.

1948 Series

Australia's first tour of England after World War II, in 1948, was led by the 39-year-old Bradman in his last appearance representing Australia. His team has gone down in cricketing legend as The Invincibles, as they played 36 matches including five Tests, and remained unbeaten on the tour. They won 27 matches, drawing only 9, including of course the 4–0 Ashes series victory.

This series is also known for one of the most poignant moments in cricket history, as Bradman batted for Australia in the fifth Test at The Oval — his last — needing to score only 4 runs to maintain a career batting average of 100. Eric Hollies bowled him second ball for a duck with a googly, denying him those 4 runs and sending him into retirement with a career average of 99.94.

1950 to 1980

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (January 2007) |

Australia gradually weakened after 1948, allowing England back into the fray in the early 1950s when they won three successive Ashes series, from 1953 to 1956 to be arguably the best Test side in the world at the time.

In 1954/55, Australia's batsmen had no answer to the pace of Frank Tyson and Brian Statham.

A see-sawing series in 1956 saw a record that will probably never be beaten: off-spinner Jim Laker's monumental effort at Old Trafford when he bowled 68 of 191 overs to take nineteen out of twenty possible Australian wickets. Never has the phrase "he won the match single-handedly" been more appropriate.

England's dominance was not to last, however. Australia thumped them 4–0 when they next toured in 1958–59, having found a good bowler of their own in Richie Benaud who took 31 wickets in the 5-Test series.

England failed to win any series during the 1960s, a period dominated by draws as teams found it more prudent to save face with a draw than risk losing. Of a total of 25 Ashes Tests playing during this decade, Australia won seven and England three. It was in the 1960s that the predominance of England and Australia in world cricket was seriously challenged for the first time. West Indies defeated England twice in the mid-sixties and then South Africa, in its last series before it was banned, completely outplayed Australia.

In 1970/71, Ray Illingworth led England to a 2-0 win in Australia, mainly because of John Snow's fast bowling, while Geoff Boycott and John Edrich scored the runs. It was not until the last session of what was the 7th Test that England's success was assured and the win was a triumph for Illingworth.

The 1972 series finished all square at 2-2, with England retaining the Ashes as a result.

By the 1974–75 series, with England going into decline and without their best batsman Geoff Boycott, Australian pace bowlers Jeff Thomson and Dennis Lillee wreaked havoc. A 4-1 result was a fair reflection as England were left shell shocked. England lost the 1975 series at home 0-1, but at least restored some pride under Tony Grieg as their new captain.

Australia won the 1977 Centenary Test (which was not an Ashes contest) but then a storm broke as Kerry Packer announced his intention to form World Series Cricket.

England was already in decline and no longer a match for West Indies. World Series Cricket damaged Australia too and for many years they struggled in Test cricket. The Ashes had long been seen as a sort of cricket world championship but that view was no longer feasible.

The 1977 series in England resulted in a 3-0 win for England under Mike Brearley. The Australian team were split and without Dennis Lillee. Brearly captained England superbly and the return to test cricket of Geoff Boycott was a resounding success as he averaged 147 in his 3 matches. Ian Botham also made his test debut in the series.

In 1978/79 Mike Brearley led England to an overwhelming 5-1 series win over an Australian side led by Graham Yallop. During this series Allan Border made his Test debut for Australia. The England team contained the likes of Boycott, Gower, Gooch, Botham and Willis and although the cricket was often not of the highest class, the Australian team were unlucky to lose so heavily.

1981 Series

Ian Botham started the series as England captain but was forced to resign or was sacked (depending on the source) after Australia took a 1-0 lead in the first two Tests of the 1981 series. Mike Brearley, who had previously retired from Test cricket, agreed to be reappointed before the Third Test at Headingley. Australia looked certain to take a 2-0 lead in the third Test when they forced England to follow-on 227 runs behind. England, despite being 135 for 7, produced a second innings total of 356 with Botham scoring 149*. Chasing just 130, Australia was dismissed for 111, with Bob Willis taking 8/43. It was the first time since 1894/95 that a team following on had won any Test match. Under Brearley's leadership, England went on to win the next two matches before a drawn final match at The Oval.

While this was an exciting and entertaining series, neither England nor Australia could match the dominant West Indies at the time.

1980s

Australia had Greg Chappell back in 1982–83, while the England team was weakened by the enforced omission of the South African rebels, particularly Graham Gooch and John Emburey. Australia went two-nil up after three Tests, but England won the fourth Test by 3 runs (after a 70-run last wicket stand) to set up the final decider. However, the game was drawn.

In 1985 England were bolstered by the return of Graham Gooch and John Emburey as well as the emergence at international level of Tim Robinson and Mike Gatting. Australia, under Allan Border were weakened by a rebel South African tour, the loss of Terry Alderman who dominated the 1981 and 1983 series a particular factor. England won 3–1, with David Gower scoring a career-high 215 in the fifth Test to help England to a 2–1-lead, and an innings win in the final test, where Gower scored 157 and Gooch 196.

The 1986/87 England side started badly and attracted some criticism.[8] However, Chris Broad got three hundreds in successive tests and bowling successes from Graham Dilley and Gladstone Small meant England won 2–1. The final test was again marred by a controversial umpiring decision as Dean Jones was given not out early on in his innings to what appeared a legitimate catch. He went on to score 185* as Australia recorded their only win. It was though a resounding win for England and few could have predicted how long it would be until they won the Ashes again as after those wins a period of extended Australian dominance began. England would have to wait until 2005 to win the Ashes again.

1989 Series

It was the Australia of old who arrived in England in 1989 and proceeded in a determined and professional manner to demolish a poor England team and win the series 4–0. Allan Border had stood firm through the lean years and now enjoyed the company of some top-class team mates with the arrival on the scene of Mark Taylor, Merv Hughes, David Boon, Ian Healy and above all Steve Waugh, who was to be a thorn in England's side for years to come. England were led once again by David Gower, but a team hit by injuries, poor form and players secretly planning to undertake a rebel tour of South Africa was no match at all for Border's team. Had the rain not intervened, a 6-0 whitewash was highly likely.

1990s

There can be little doubt that England reached rock-bottom in the 1990s and was at one stage at the foot of the international rankings. After re-establishing its credibility in 1989, Australia underlined its superiority with a succession of victories in 1990/91, 1993, 1994/95, 1997, 1998/99, 2001 and 2002/03 series — all by convincing margins.

Great Australian players in these years were fast bowler Glenn McGrath; wicketkeeper-batsman Adam Gilchrist; batsmen Justin Langer, Damien Martyn and Ricky Ponting who succeeded Waugh as captain after 2002/03; and leg-spin bowler Shane Warne.

Australia's record since 1989 has impacted upon the overall statistics between the two sides. Before the 1989 series began, Australia had won 36.9% of all Tests played against England, England 33.5% with 29.7% of matches ending in draws. Previous to the 2005 series, Australia had won 40.8% of all Tests, England 31% with 28.1% drawn.[9]

In the period between 1989 and the beginning of the 2005 series, the two sides had played 43 times; Australia winning 28 times, England 7 times, with 8 draws. Even more astonishingly, only a single England victory had come in a match in which the Ashes were still at stake, namely the first Test of the 1997 series. All others were consolation victories when the Ashes had been secured by Australia.[10]

2005 Series

England were undefeated in Test matches in the 2004 calendar year, which took the team to second in the LG ICC Test Championship and raised hopes that the 2005 Ashes series would be closely fought. In fact, the series was even more competitive than anyone had predicted, and was still undecided as the final session of the final test began. The first Test at Lord's was convincingly won by Australia, but in the remaining four matches the teams were evenly matched, and England fought back. England won the second Test by 2 runs, the smallest victory by a runs margin in Ashes history, and the second-closest such victory in all Tests. The rain-affected third Test ended with the last two Australian batsmen holding out for a draw, and England won the fourth Test by three wickets after forcing Australia to follow on for the first time in 191 Tests. A draw in the final Test gave England victory in an Ashes series for the first time in 18 years, and their first Ashes victory at home since 1985. Experienced journalists including Richie Benaud rated the series as the most exciting in living memory. It has been compared with the great series of the distant past, such as 1894/95 and 1902.

2006–07 series

Australia regained The Ashes in the 2006–07 series by winning 5-0, only the second ever Ashes whitewash (after Australia's 5-0 victory in 1920–21, the first series after World War I). Determined to avenge their defeat of 2005, they took advantage of England's failure to maintain pressure at key moments. Glenn McGrath, Shane Warne and Justin Langer, three of Australia's greatest cricketers, retired from Test cricket at the end of the series, whilst Damien Martyn (who is gay) retired halfway through the series.

Summary of results and statistics

- See also: List of Ashes series for a full listing of all the Ashes series since 1882.

|

A team must win a series to gain the right to hold the Ashes. A drawn series results in the previous holders retaining the Ashes. To date, a total of 64 Ashes series have been played, with Australia winning 31 and England 28. The remaining five series were drawn, with Australia retaining the Ashes four times (1938, 1962–63, 1965–66, 1968) and England retaining it once (1972).

Ashes series have generally been played over five Test matches, although there have been four match series (1938; 1975) and six match series (1970–71; 1974–75; 1978–79; 1981; 1985; 1989; 1993 and 1997). 315 matches have been played, with Australia winning 121 times, England 94 times, and 88 draws. Australians have made 264 centuries in Ashes Tests, twenty-three of them over 200, while Englishmen have scored 212 centuries, of which ten have been scores over 200. On 41 occasions, individual Australians have taken ten wickets in a match. Englishmen have performed that feat 38 times.

The Ashes today

The Ashes is one of the most fiercely contested competitions in cricket.

The failure of England to regain the Ashes for 16 years from 1989, coupled with the global dominance of the Australian team, had dulled the lustre of the series in recent years throughout most of the cricketing world, although it has remained the most popular cricketing contest for Australians. However the close results in the 2005 Ashes series, and the overall high quality and competitiveness of the cricket greatly boosted the popularity of the sport in Britain and considerably enhanced the profile of the Ashes around the world. It remains to be seen whether the lopsided results of the 2006-07 Ashes series will have a negative impact on this newly acquired popularity outside of Australia.

Match venues

The series alternate between England and Australia, and within each country each of the (usually) five matches is held at a different cricket ground.

In Australia, the grounds currently used are "The Gabba" in Brisbane (first staged an England-Australia Test in the 1932–33 season), Adelaide Oval (1884–85), The WACA, Perth (1970–71) the Melbourne Cricket Ground (MCG) (1876–77) and the Sydney Cricket Ground (SCG) (1881–82). One Test was held at the Brisbane Exhibition Ground in 1928–29. Traditionally, Melbourne hosts the Boxing Day Test. Cricket Australia has proposed that the 2010–11 series consist of six tests, with the additional game to be played at Bellerive Oval in Hobart. The England Cricket Board is yet to agree to this.

In England the grounds used are The Oval (since 1880), Old Trafford (1884), Lord's (1884), Trent Bridge (1899), Headingley (1899) and Edgbaston (1902). One Test was held at Bramall Lane, Sheffield in 1902. Sophia Gardens in Cardiff, Wales is scheduled to hold its first Ashes Test in 2009.

The Ashes outside cricket

The popularity and reputation of the cricket series has led to many other events taking the name for England against Australia contests. The best-known and longest-running of these events is the rugby league contest between Great Britain and Australia (see Rugby League Ashes). The contest first started in 1908, the name being suggested by the touring Australians. Another example is in the British television show Gladiators, where two series were based around the Australia–England contest.

The urn is also featured in the science fiction comedy novel Life, the Universe and Everything, the third "Hitchhiker's Guide To The Galaxy" book by Douglas Adams. The urn is stolen by alien robots, as it is part of the key needed to unlock the "Wikkit Gate" and release the imprisoned world of "Krikkit".

In the cinema, the Ashes featured in the film The Final Test, released in 1953, based on a television play by Terence Rattigan. It stars Jack Warner as an England cricketer playing the last Test of his career, which is the last of an Ashes series; the film contains cameo appearances from prominent contemporary Ashes cricketers including Jim Laker and Denis Compton.[11]

See also

- Ball of the Century

- History of Test cricket (to 1883)

- History of Test cricket (1884 to 1889)

- History of Test cricket (1890 to 1900)

Notes

- ^ In 2006–07 the urn was taken to Australia and exhibited at each of the Test match grounds to coincide with the England tour.

- ^ Fred Spofforth, however, held that, the fourth innings aside, it played perfectly well.

- ^ Spofforth's nickname.

- ^ Gibson, A., Cricket Captains of England, p26.

- ^ Ronald Willis - Cricket's biggest Mystery: The Ashes ISBN 0-7270-1768-3

- ^ Joy Munns - Beyond Reasonable Doubt: The birthplace of the Ashes ISBN 0-646-22153-1

- ^ Ashes — The Beginning, 334 Not out

- ^ Cricinfo - Can't bat, can't bowl, can't field

- ^ Statistics obtained from Cricinfo at [1]

- ^ Statistics obtained from Cricinfo at [2]

- ^ "The Final Test (1953)". Internet Movie Database. Retrieved 2006-11-16.

References

- Birley, D. (2003). A Social History of English Cricket. London: Aurum Press. ISBN 1-85410-941-3.

- Frith, D. (1990). Australia versus England: a pictorial history of every Test match since 1877. Victoria (Australia): Penguin Books. ISBN 0-670-90323-X.

- Gibb, J. (1979). Test cricket records from 1877. London: Collins. ISBN 0-00-411690-9.

- Gibson, A. (1989). Cricket Captains of England. London: Pavilion Books. ISBN 1-85145-395-4.

- Green, B. (1979). Wisden Anthology 1864–1900. London: M & J/QA Press. ISBN 0-356-10732-9.

- Munns, J. (1994). Beyond reasonable doubt - Rupertswood, Sunbury - the birthplace of the Ashes. Australia: Joy Munns. ISBN 0-646-22153-1.

- Warner, P. (1987). Lord's 1787–1945. London: Pavilion Books. ISBN 1-85145-112-9.

- Warner, P. (2004). How we recovered the Ashes : MCC Tour 1903–1904. London: Methuen. ISBN 0-413-77399-X.

- Wynne-Thomas, P. (1989). The complete history of cricket tours at home and abroad. London: Hamlyn. ISBN 0-600-55782-0.

- "The Ashes". Marylebone Cricket Club. Retrieved 2007-01-02.

Other

- Wisden's Cricketers Almanack (various editions)

External links

- MCC Museum's history of the Ashes

- Visit the Ashes urn at Lord's

- Cricinfo's Ashes site

- History of the Ashes published by Melbourne Cricket Club Library

- The Origin of the Ashes - Rex Harcourt

- The Ashes Tray

- Ashes that Aussies can’t win - Article in The Telegraph