Weather Underground: Difference between revisions

m Reverted edits by 67.174.7.158 (talk) to last version by Wnjr |

m →Referred to as a terrorist group: fix typos, combine one-sentence paragraph into paragraph below it |

||

| (One intermediate revision by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 13: | Line 13: | ||

The evacuation warning issued in their communiqués included statements indicating the particular event to which they were responding. For the bombing of the [[United States Capitol]] on [[March 1]], [[1971]], they issued a statement saying it was "in protest of the US invasion of [[Laos]]." For the bombing of [[The Pentagon]] on [[May 19]], [[1972]], they stated it was "in retaliation for the US bombing raid in [[Hanoi]]." For the [[January 29]], [[1975]] bombing of the [[Harry S Truman Building]] housing the [[United States Department of State]], they stated it was "in response to escalation in [[Vietnam War|Vietnam]]."<ref name="The Weather Underground"/> The Weathermen largely disintegrated shortly after the US reached a peace accord in Vietnam in 1973 , which saw the general decline of the [[New Left]]. |

The evacuation warning issued in their communiqués included statements indicating the particular event to which they were responding. For the bombing of the [[United States Capitol]] on [[March 1]], [[1971]], they issued a statement saying it was "in protest of the US invasion of [[Laos]]." For the bombing of [[The Pentagon]] on [[May 19]], [[1972]], they stated it was "in retaliation for the US bombing raid in [[Hanoi]]." For the [[January 29]], [[1975]] bombing of the [[Harry S Truman Building]] housing the [[United States Department of State]], they stated it was "in response to escalation in [[Vietnam War|Vietnam]]."<ref name="The Weather Underground"/> The Weathermen largely disintegrated shortly after the US reached a peace accord in Vietnam in 1973 , which saw the general decline of the [[New Left]]. |

||

== Referred to as a terrorist group == |

|||

Since 1970 the Weatherman organization has often, but not always, been classified in America as a domestic terrorist organization. "Within the political youth movement of the late sixties (outside of Latin America), the 'Weathermen' were the first group to reach the front page because of terrorist activities," wrote Klaus Mehnert in his 1977 book, "Twilight of the Young, The Radical Movements of the 1960s and Their Legacy".<ref>Mehnert, Klaus, "Twilight of the Young, The Radical Movements of the 1960s and Their Legacy", Holt, Reinhart and Winston, 1977, page 47</ref> Neil A. Hamilton, in his 1996 book on militia movements in the United States, wrote, "By and large, though, these Weathermen did not rely on arming and training militia; instead, they resorted to terrorism."<ref>Hamilton, Neil A., "Militias in America: A Reference Handbook", a volume in the "Contemporary World Issues" series, Santa Barbara, California, 1996, page 15; ISBN 0874368596; the book identifies its author this way: "Neil A. Hamilton is associate professor and chair of the history department at Spring Hill College in Mobile, Alabama"</ref> |

|||

Starting in 1970 newspapers covering their bombing of public buildings identified the group as "terrorist".<ref>No byline, UPI wire story, "Weathermen Got Name From Song: Groups Latest Designation Is Weather Underground", as published in ''[[The New York Times]]'', [[January 30]], [[1975]]; "On Jan. 19, 1971, Bernardine Dohrn, a leading Weatherperson who has never been caught, issued a statement from hiding suggesting that the group was considering tactics other than bombing and '''terrorism.'''""; Montgomery, Paul L., "Guilty Plea Entered in 'Village' Bombing: Cathlyn Wilkerson Could Be Given Probation or Up to 7 Years", article, ''[[The New York Times]]'', July 19, 1980: "the terrorist Weather Underground"</ref> Michael Charney, a spokesman for the rival Oberlin Radical Coalition, told The New York Times that year that the Weathermen resorted to terrorism because Americans were unwilling to participate in a revolution. Thomas Powers and Lucinda Franks wrote the Pulitzer-prize-winning news series, "Diana: The Making of a Terrorist" about the life and death of member Diana Oughton (later expanded into a full-length authorized biography on the subject). The group fell under the auspicies of FBI-New York City Police Anti Terrorist Task Force, a forerunner of the FBI's Joint Terrorism Task Forces. The FBI, on its website, describes organization as having been a "domestic terrorist group", but no longer an active concern.<ref>Web page titled, [http://www.fbi.gov/page2/jan04/weather012904.htm "BYTE OUT OF HISTORY: 1975 Terrorism Flashback: State Department Bombing"], at F.B.I. website, dated [[January 29]], [[2004]], retrieved [[September 2]], [[2008]]</ref> |

|||

Others either dispute or clarify the categorization, or justify the group's violence as an appropriate response to the Vietnam war. In his 2001 book about his Weatherman experiences, [[Bill Ayers]] stated his objection to describing the WUO (Weather Underground Organization) as "terrorist". Ayers wrote: "Terrorists terrorize, they kill innocent civilians, while we organized and agitated. Terrorists destroy randomly, while our actions bore, we hoped, the precise stamp of a cut diamond. Terrorists indimidate, while we aimed only to educate. No, we're not terrorists."<ref>Ayers, Bill, ''Fugitive Days'', Beacon Press, ISBN 0807071242, p 263</ref> Dan Berger, in his book about the Weatherman, ''Outlaws in America'', quotes Ayers' objection, then adds, The WUO's actions were more than just educational — one could argue that there was a component of 'intimidating' the government and police attached to the actions — bu the group purposefully and successfully avoided injuring anyone, not just civilians but armed enforcers of the government. Its war against property by definition means that the WUO was not a terrorist organization — it was, indeed, one deeply opposed to the tactic of terrorism." Berger also describes the organization's activities as "a moral, pedagogical, and militant form of guerrilla theater with a bang."<ref>Berger, Dan, ''Outlaws of America: The Weather Underground and the Politics of Solidarity'', AK Press: Oakland, California, 2006, ISBN 1904859410 pp 286-287; the book describes Berger as "a writer, activist, and Ph.D. candidate", and the book is dedicated to his grandmother and to Weatherman member [[David Gilbert]]</ref> |

|||

== Background and formation == |

== Background and formation == |

||

The group emerged from the campus-based [[opposition to the Vietnam War]], as well as the [[Civil Rights Movement]]s of the late 1960s. During this time, [[United States military]] action in [[Southeast Asia]], especially in [[Vietnam War|Vietnam]], escalated. In the U.S., the anti-war sentiment was particularly pronounced during the [[U.S. presidential election, 1968|1968 U.S. presidential election]]. |

The group emerged from the campus-based [[opposition to the Vietnam War]], as well as the [[Civil Rights Movement]]s of the late 1960s. During this time, [[United States military]] action in [[Southeast Asia]], especially in [[Vietnam War|Vietnam]], escalated. In the U.S., the anti-war sentiment was particularly pronounced during the [[U.S. presidential election, 1968|1968 U.S. presidential election]]. |

||

Revision as of 03:57, 3 September 2008

Weatherman, known colloquially as the Weathermen and later the Weather Underground Organization, was an American radical left organization founded in 1969 by leaders and members who split from the Students for a Democratic Society (SDS). The group organized a riot in Chicago in 1969 and bombed buildings in the 1970s.

They took their name from the lyric "You don't need a weatherman to know which way the wind blows," from the Bob Dylan song Subterranean Homesick Blues. They also used this lyric as the title of a position paper they distributed at an SDS convention in Chicago on June 18, 1969, as part of a special edition of New Left Notes. The Weathermen were initially part of the Revolutionary Youth Movement (RYM) within the SDS, splitting from the RYM's Maoists by claiming there was no time to build a vanguard party and that revolutionary war against the United States government and the capitalist system should begin immediately. Their founding document called for the establishment of a "white fighting force" to be allied with the "Black Liberation Movement" and other "anti-colonial" movements[1] to achieve "the destruction of US imperialism and achieve a classless world: world communism."[2]

The group's first public demonstration was the "Days of Rage," an October 8, 1969 riot in Chicago that was coordinated with the trial of the Chicago Eight.[3] In 1970 the group issued a "Declaration of a State of War" against the United States government, under the name "Weather Underground Organization" (WUO), and members adopted fake identities and pursued covert activities. They carried out a campaign consisting of bombings, jailbreaks, and riots. Their attacks were mostly bombings of government buildings, along with several banks, police department headquarters and precincts, state and federal courthouses, and state prison administrative offices.[4][5]

Apart from an apparently accidental premature detonation of a bomb in the Greenwich Village townhouse explosion which claimed the lives of three of its own members, no one was ever harmed in the extensive bombing campaign, as WUO issued warnings in advance to ensure a safe evacuation of the area prior to detonation.[6][7] However, according to Mark Rudd, one of the founders of the Weathermen, the group that constructed the bomb that exploded prematurely in Greenich Village had planned to set it off at a dance in an Army NCO club, which presumably would have had lethal consequences. [1] Their activities have often been characterized as domestic terror,[8] including a later description by the FBI.[9]

The evacuation warning issued in their communiqués included statements indicating the particular event to which they were responding. For the bombing of the United States Capitol on March 1, 1971, they issued a statement saying it was "in protest of the US invasion of Laos." For the bombing of The Pentagon on May 19, 1972, they stated it was "in retaliation for the US bombing raid in Hanoi." For the January 29, 1975 bombing of the Harry S Truman Building housing the United States Department of State, they stated it was "in response to escalation in Vietnam."[6] The Weathermen largely disintegrated shortly after the US reached a peace accord in Vietnam in 1973 , which saw the general decline of the New Left.

Referred to as a terrorist group

Since 1970 the Weatherman organization has often, but not always, been classified in America as a domestic terrorist organization. "Within the political youth movement of the late sixties (outside of Latin America), the 'Weathermen' were the first group to reach the front page because of terrorist activities," wrote Klaus Mehnert in his 1977 book, "Twilight of the Young, The Radical Movements of the 1960s and Their Legacy".[10] Neil A. Hamilton, in his 1996 book on militia movements in the United States, wrote, "By and large, though, these Weathermen did not rely on arming and training militia; instead, they resorted to terrorism."[11]

Starting in 1970 newspapers covering their bombing of public buildings identified the group as "terrorist".[12] Michael Charney, a spokesman for the rival Oberlin Radical Coalition, told The New York Times that year that the Weathermen resorted to terrorism because Americans were unwilling to participate in a revolution. Thomas Powers and Lucinda Franks wrote the Pulitzer-prize-winning news series, "Diana: The Making of a Terrorist" about the life and death of member Diana Oughton (later expanded into a full-length authorized biography on the subject). The group fell under the auspicies of FBI-New York City Police Anti Terrorist Task Force, a forerunner of the FBI's Joint Terrorism Task Forces. The FBI, on its website, describes organization as having been a "domestic terrorist group", but no longer an active concern.[13]

Others either dispute or clarify the categorization, or justify the group's violence as an appropriate response to the Vietnam war. In his 2001 book about his Weatherman experiences, Bill Ayers stated his objection to describing the WUO (Weather Underground Organization) as "terrorist". Ayers wrote: "Terrorists terrorize, they kill innocent civilians, while we organized and agitated. Terrorists destroy randomly, while our actions bore, we hoped, the precise stamp of a cut diamond. Terrorists indimidate, while we aimed only to educate. No, we're not terrorists."[14] Dan Berger, in his book about the Weatherman, Outlaws in America, quotes Ayers' objection, then adds, The WUO's actions were more than just educational — one could argue that there was a component of 'intimidating' the government and police attached to the actions — bu the group purposefully and successfully avoided injuring anyone, not just civilians but armed enforcers of the government. Its war against property by definition means that the WUO was not a terrorist organization — it was, indeed, one deeply opposed to the tactic of terrorism." Berger also describes the organization's activities as "a moral, pedagogical, and militant form of guerrilla theater with a bang."[15]

Background and formation

The group emerged from the campus-based opposition to the Vietnam War, as well as the Civil Rights Movements of the late 1960s. During this time, United States military action in Southeast Asia, especially in Vietnam, escalated. In the U.S., the anti-war sentiment was particularly pronounced during the 1968 U.S. presidential election.

The origins of the Weathermen can be traced to the collapse and fragmentation of the Students for a Democratic Society. The split between the mainstream leadership of SDS, or "National Office," and the Progressive Labor Party pushed SDS as a whole further to the left. National Office leaders such as Bernardine Dohrn and Mike Klonsky began announcing their emerging perspectives, and Klonksy published a document entitled "Toward a Revolutionary Youth Movement" (RYM). RYM promoted the philosophy that young workers possessed the potential to be a revolutionary force to overthrow capitalism, if not by themselves then by transmitting radical ideas to the working class. Klonsky's document reflected the growing leftist philosophy of the National Office and was eventually adopted as official SDS doctrine. During the Summer of 1969, the National Office began to split. A group led by Klonsky became known as RYM II, and the other side, RYM I, was led by Dohrn and endorsed more aggressive tactics, as some members felt that years of non-violent resistance had done little or nothing to stop the Vietnam War.[6]

We petitioned, we demonstrated, we sat in. I was willing to get hit over the head, I did; I was willing to go to prison, I did. To me, it was a question of what had to be done to stop the much greater violence that was going on.

SDS Convention, 1969

At an SDS convention in Chicago on June 18, 1969, the National Office attempted to convince unaffiliated delegates not to endorse Progressive Labor ideals. At the beginning of the convention, two position papers were passed out by the National Office leadership, one a revised statement of Klonksy's RYM manifesto, the other called "You Don't Need a Weatherman to Know Which Way the Wind Blows." The latter document outlined the position of the group that would become the Weathermen. It had been signed by 11 people, including Mark Rudd, Bernardine Dohrn, John Jacobs, Bill Ayers, Jim Mellen, Terry Robbins, Karen Ashley, Jeff Jones, Gerry Long, and Steve Tappis.

After the summer of 1969 fragmentation of Students for a Democratic Society, Weatherman's adherents explicitly claimed themselves the real leaders of SDS and retained control of the SDS National Office. Thereafter, any leaflet, label, or logo bearing the name "Students for a Democratic Society" or "SDS" was in fact the views and politics of Weatherman, and not of SDS as a whole. Weatherman contained the vast majority of former SDS National Committee members, including Mark Rudd, David Gilbert and Bernadine Dohrn. For this reason, the group, while small, was able to easily commandeer the mantle of SDS and all of its membership lists. For a brief time, affiliations with regional SDS cadre were maintained from the National Office, but with Weatherman in charge the relationships did not last long, and local chapters soon disbanded. By February 1970, the group had decided to close the SDS National Office, concluding the major campus-based organization of the 1960s.

Ideology

The name Weatherman was derived from the Bob Dylan song “Subterranean Homesick Blues”, which featured the lyrics “You don’t need a weatherman to know which way the wind blows.” The lyrics had been quoted at the bottom of an influential essay in the SDS newspaper, New Left Notes. Using this title the Weathermen meant, partially, to appeal to the segment of American youth inspired to action for social justice by Dylan’s songs. It appears also that the “Weatherman” moniker used by the group may have been meant as a rebuke against the Progressive Labor Party, whose Worker Student Alliance SDS faction had succeeded in recruiting many former SDSers to its ranks, and had allegedly co-opted the 1969 convention.

The Weatherman group had long held that militancy was becoming more important than nonviolent forms of anti-war action, and that university-campus-based demonstrations needed to be punctuated with more dramatic actions, which had the potential to interfere with the U.S. military and internal security apparatus. The belief was that these types of urban guerrilla actions would act as a catalyst for the coming revolution. Many international events indeed seemed to support the Weathermen’s overall assertion that worldwide revolution was imminent, such as the tumultuous Cultural Revolution in China; the 1968 student revolts in France, Mexico City and elsewhere; the Prague Spring; the emergence of the Tupamaros organization in Uruguay; the emergence of the Guinea-Bissauan Revolution and similar Marxist-led independence movements throughout Africa; and within the United States, the prominence of the Black Panther Party together with a series of “ghetto rebellions” throughout poor black neighborhoods across the country.[16]

We felt that doing nothing in a period of repressive violence is itself a form of violence. That's really the part that I think is the hardest for people to understand. If you sit in your house, live your white life and go to your white job, and allow the country that you live in to murder people and to commit genocide, and you sit there and you don't do anything about it, that's violence.

The Weathermen were outspoken advocates of the critical concepts that later came to be known as “white privilege” and identity politics.[citation needed] As the unrest in poor black neighborhoods intensified in the early 1970s, Bernardine Dohrn said, “White youth must choose sides now. They must either fight on the side of the oppressed, or be on the side of the oppressor.”[6]

Activities

"Days of Rage"

One of the first things the Weathermen did upon splitting from SDS was to announce that they would hold the "Days of Rage" that fall. The event was advertised with the slogan "Bring the war home!" Hoping to cause chaos on a level able to "wake" the American public out of what the group saw as the public's complacency toward the role of the US in the Vietnam War that claimed the lives of between 3 and 5 million Vietnamese, the Weathermen wanted the event to be the largest-scale protest the decade had seen. The Weathermen had been told by their regional cadre to expect thousands in attendance, but when they arrived, they found a crowd of only a few hundred people. According to Bill Ayers, "The Days of Rage was an attempt to break from the norms of kind of acceptable theatre of 'here are the anti-war people: containable, marginal, predictable, and here's the little path they're going to march down, and here's where they can make their little statement.' We wanted to say, "No, what we're going to do is whatever we had to do to stop the violence in Vietnam.'"[6]

Shortly before the demonstrations, they blew up a statue dedicated to police casualties in the 1886 Haymarket Riot (right), placing a bomb between its legs.[17] The blast broke nearly 100 windows and scattered pieces of the statue onto the Kennedy Expressway below.[18] The statue was rebuilt and unveiled on May 4, 1970, and then blown up again by Weatherman on October 6, 1970.[19][18] The statue was again rebuilt and Mayor Richard J. Daley posted a 24-hour police guard at the statue.[18]

Although the October 8, 1969 rally in Chicago had failed to draw as many participants as they had anticipated (originally expecting 10,000), the estimated two to three hundred who did attend shocked police by leading a riot through the affluent Gold Coast neighborhood, smashing windows of a bank and then those of many cars. The mass of the crowd ran about four blocks before encountering police barricades. The mob charged the police but splintered into small groups, and more than 1,000 police counter-attacked. Although many protesters were wearing motorcycle or football helmets, the police were better trained and armed and nightsticks were aimed at necks, legs and groins. Large amounts of tear gas were used, and at least twice police ran squad cars full speed into crowds. The riot lasted approximately half an hour, with 28 policemen injured (none seriously), six Weathermen shot by police, an unknown number injured, and 68 protesters arrested.[1][17][20][21]

For the next two days, Weatherman held no rallies or protests. Supporters of the RYM II movement, led by Klonsky and Noel Ignatin, held peaceful rallies of several hundred people in front of the federal courthouse, an International Harvester factory, and Cook County Hospital. The largest event of the Days of Rage occurred on Friday, October 9, when RYM II led an interracial march of 2,000 people through a Spanish-speaking part of Chicago.[1][20]

On Saturday, October 10, Weatherman attempted to regroup and resume their demonstrations. Approximately 300 protesters marched swiftly through The Loop, Chicago's main business district, watched over by a double-line of heavily armed police. The protesters suddenly broke through the police lines and rampaged through the Loop, smashing windows of cars and stores. But the police were prepared, and quickly sealed off the protesters. Within 15 minutes, more than half the crowd had been arrested.[1][20]

The Days of Rage cost Chicago and the state of Illinois approximately $183,000 ($100,000 for National Guard payroll, $35,000 in damages, and $20,000 for one injured citizen's medical expenses). Most of the Weathermen and SDS leaders were jailed, and the Weatherman bank account was emptied of more than $243,000 in order to pay for bail.[21]

Declaration of a State of War

In December 1969, the Chicago Police Department, in conjunction with the FBI, conducted a raid on the home of Black Panther Fred Hampton, in which he and Mark Clark were killed, with four of the seven other people in the apartment wounded. The survivors of the raid were all charged with assault and attempted murder. The police claimed they shot in self-defense, although a controversy arose when the Panthers and other activists presented what was alleged to be evidence suggesting that the sleeping Panthers were not resisting arrest. The charges were later dropped, and the families of the dead won a $1.8 million settlement from the government. It was discovered in 1971 that Hampton had been targeted by the FBI's COINTELPRO.[22][23]

We felt that the murder of Fred required us to be more grave, more serious, more determined to raise the stakes and not just be the white people who wrung their hands when black people were being murdered.

In 1970 the group issued a "Declaration of a State of War" against the United States government, using for the first time its new name, the "Weather Underground Organization" (WUO), adopting fake identities, and pursuing covert activities only. These initially included preparations for a bombing of a U.S. military non-commissioned officers' dance at Fort Dix, New Jersey in what Brian Flanagan said had been intended to be "the most horrific hit the United States government had ever suffered on its territory".[24]

Anti-personnel bomb set on window-ledge in San Francisco

In a bombing that took place on February 16, 1970, and that was credited to the Weathermen at the time,[25][26] a pipe bomb filled with heavy metal staples and lead bullet projectiles was set off on the ledge of a window at the Park Station of the San Francisco Police Department. In the blast, Brian V. McDonnell, a police sergeant, was fatally wounded while Robert Fogarty, another police officer, received severe wounds to his face and legs and was partially blinded.[27]

Weatherman leader Bernardine Dohrn has been suspected of involvement in the February 16, 1970, bombing of the Park Police Station in San Francisco. At the time, Dohrn was said to be living with a Weatherman cell in a houseboat in Sausalito, California, unnamed law enforcement sources later told KRON-TV.[28] An investigation into the case was reopened in 1999,[29] and a San Francisco grand jury looked into the incident, but no indictments followed,[28] and no one was ever arrested for the bombing.[29] An FBI informant, Larry Grathwohl, who successfully penetrated the organization from the late summer of 1969 until April 1970, later testified to a U.S. Senate subcommittee that Bill Ayers, then a high-ranking member of the organization and a member of its Central Committee (but not then Dohrn's husband), had said Dohrn constructed and planted the bomb. Grathwohl testified that Ayers had told him specifically where the bomb was placed (on a window ledge) and what kind of shrapnel was put in it. Grathwohl said Ayers was emphatic, leading Grathwohl to believe Ayers either was present at some point during the operation or had heard about it from someone who was there.[30] In a book about his experiences published in 1976, Grathwohl wrote that Ayers, who had recently attended a meeting of the group's Central Committee, said Dohrn had planned the operation, made the bomb and placed it herself.[31] In 2008, author David Freddoso commented that "Ayers and Dohrn escaped prosecution only because of government misconduct in collecting evidence against them".[30][32]

Initial New York City Bombings

Early on the morning of February 21, 1970 as his family slept, three gasoline-filled firebombs exploded at at home of New York State Supreme Court Justice Murtagh's at the northern tip of Manhattan. The same night, bombs were thrown at a police car in Manhattan and two military recruiting stations in Brooklyn.

Judge Murtagh was presiding over the trial of the so-called “Panther 21,” members of the Black Panther Party indicted in a plot to bomb New York landmarks and department stores. The side-walk in front of his home had three sentences of blood-red graffiti: "FREE THE PANTHER 21; THE VIET CONG HAVE WON; KILL THE PIGS."

Only a few weeks after the attack, the New York contingent of the Weathermen blew themselves up making more bombs in a Greenwich Village townhouse (see below). The same cell had bombed Judge Murtagh's house, according to Ron Jacobs in The Way the Wind Blew: A History of the Weather Underground. In late November of 1970, a letter to the Associated Press signed by Bernardine Dohrn, now Bill Ayers's wife, promised more bombings.[33]

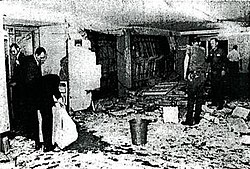

Greenwich Village explosion

On March 6, 1970, during preparations for the bombing of an officers' dance at the Fort Dix U.S. Army base and for Butler Library at Columbia University,[34] there was an explosion in a Greenwich Village safe house when the bomb being constructed prematurely detonated due to a wiring malfunction. WUO members Diana Oughton, Ted Gold, and Terry Robbins died in the explosion. Cathy Wilkerson and Kathy Boudin escaped unharmed, Wilkerson running naked from the apartment. It was an accident of history that the site of the Village explosion was the former residence of Merrill Lynch brokerage firm founder Charles Merrill and his son, the poet James Merrill. The younger Merrill subsequently recorded the event in his poem 18 West 11th Street, the title being the address of the house. An FBI report later stated that the group had possessed sufficient amounts of explosive to "level ... both sides of the street".[35]

The bomb preparations have been pointed out by critics of the claim that the Weatherman group did not try to take lives with its bombings. Harvey Klehr, the Andrew W. Mellon professor of politics and history at Emory University in Atlanta, said in 2003, "The only reason they were not guilty of mass murder is mere incompetence. I don't know what sort of defense that is."[34]

Underground

After the Greenwich Village incident, the group was now well underground, and began to refer to themselves as the Weather Underground Organization. At this juncture, WUO shrank considerably, becoming even fewer than they had been when first formed. The group was devastated by the loss of their friends, and in late April, 1970, members of the Weathermen met in California to discuss what had happened in New York and the future of the organization. The group decided to reevaluate their strategy, particularly in regard to their initial belief in the acceptability of human casualties, rejecting such tactics as kidnapping and assassinations.

They wanted to convince the American public that the United States was truly responsible for the calamity in Vietnam.[6] The group began striking at night, bombing empty offices, with warnings always issued in advance to ensure a safe evacuation. According to David Gilbert, "[their] goal was to not hurt any people, and a lot of work went into that. But we wanted to pick targets that showed to the public who was responsible for what was really going on."[6] After the Greenwich Village explosion, no one was killed by WUO bombs.[7]

We were very careful from the moment of the townhouse on to be sure we weren't going to hurt anybody, and we never did hurt anybody. Whenever we put a bomb in a public space, we had figured out all kinds of ways to put checks and balances on the thing and also to get people away from it, and we were remarkably successful.

On 21 May 1970, a communiqué from the Weather Underground was issued promising to attack a "symbol or institution of American injustice" within two weeks.[36] The communiqué included taunts towards the FBI, daring them to try and find the group, whose members were spread throughout the United States.[37] Many leftist organizations showed curiosity in the communiqué, and waited to see if the act would in fact occur. However, two weeks would pass without any occurrence.[38] Then on 9 June 1970, their first publicly acknowledged bombing occurred at a New York City police station,[39] saying it was "in outraged response to the assassination of the Soledad Brother George Jackson,"[6] who had recently been killed by prison guards in an escape attempt. The FBI placed the Weather Underground organization on the ten most-wanted list by the end of 1970.[17] On 19 May 1972, Ho Chi Minh’s birthday, The Weather Underground placed a bomb in the women’s bathroom in the Air Force wing of The Pentagon. The damage caused flooding that devastated vital classified information on computer tapes. Leftist groups worldwide applauded the bombing, illustrated by German youth protesting against American military systems in Frankfurt.[17]

Change in direction, Prairie Fire

The Weather Underground’s ideology changed direction in the early 1970’s. With help from former Progressive Labor member, Clayton Van Lydegraf, The Weather Underground sought a more Marxist-Leninist approach. The leading members of the Weather Underground collaborated ideas and published their manifesto: "Prairie Fire: The Politics of Revolutionary Anti-Imperialism."[17] By the summer of 1974, five thousand copies had surfaced in coffee houses and bookstores across America. Leftist newspapers praised the manifesto.[40] Abbie Hoffman publicly praised Prairie Fire and believed every American should be given a copy.[41] The manifesto’s influence initiated the formation of the 'Prairie Fire Organizing Committee' in several American cities. Hundreds of above-ground activists helped further the new political vision of the Weather Underground.[40] In the late 1970s, the Weatherman group further split into two factions — the "May 19 Coalition" and the "Prairie Fire Collective" — with Bernadine Dohrn and Bill Ayers in the latter. The Prairie Fire Collective favored coming out of hiding, with members facing the criminal charges against them, while the May 19 Coalition continued in hiding. A decisive factor in Dohrn's coming out of hiding were her concerns about her children.[42]. The Prairie Fire Collective started to surrender to the authorities from the late 1970s to the earyl 1980s. The remaining Weatherman Underground members continued to violently attack US institutions.

Timothy Leary prison break

In September 1970, the group took a $25,000 payment from a psychedelics distribution organization called The Brotherhood of Eternal Love to break LSD advocate Timothy Leary out of prison[citation needed], transporting him and his wife to Algeria. Leary joined Eldridge Cleaver in Algeria; his initial press release contains revolutionary rhetoric sympathetic to the Weather Underground's cause. When Leary was eventually captured by the FBI, it is alleged he offered to serve as an informant to capture the Weather Underground members to reduce his prison sentence. Others, such as Robert Anton Wilson, claim he was just feeding false information to the authorities in an attempt to reduce his sentence. Ultimately no one was charged, and Leary served a few more years in prison.[citation needed]

Brinks Armed Robbery of 1981

On October 20, 1981 the Weather Underground combined forces with the Black Liberation Army to rob a Brink's armored truck. Two policemen and a Brink's guard were killed. The Black Liberation Army members Jeral Wayne Williams (aka Mutulu Shakur), Donald Weems (aka Kuwasi Balagoon), Samuel Smith and Nathaniel Burns (aka Sekou Odinga), Cecilio "Chui" Ferguson, Samuel Brown (aka Solomon Bouines) with five members of the Weather Underground (David Gilbert, Samuel Brown, Judith Alice Clark, Kathy Boudin, and Marilyn Buck) stole $1.6 million from a Brink's armored car at the Nanuet Mall, in Nanuet, New York. All the perpertrators were eventually captured and tried. Kathy Boudin's child with David Gilbert, Chesa, was raised to adulthood by Bill Ayers and Bernadine Dohrn, while she was in prison.

Dissolution and aftermath

COINTELPRO

In April 1971, The "Citizens' Commission to Investigate the FBI" broke into an FBI office in Media, Pennsylvania.[43] The group stole files with several hundred pages, ninety-eight percent of the files targeted left wing individuals and groups. By the end of April, the FBI offices were to terminate all files dealing with leftist groups.[44] The files were a part of an FBI program called COINTELPRO.[45] However, after COINTELPRO was dissolved in 1971 by J. Edgar Hoover,[46] the FBI continued their counterintelligence on groups like the Weather Underground. In 1973, the FBI established the 'Special Target Information Development' program, where agents were sent undercover to penetrate the Weather Underground. Due to the illegal tactics of FBI agents involved with the program, government attorneys requested all weapons and bomb related charges be dropped against the Weather Underground. The Weather Underground was no longer a fugitive organization and could turn themselves in with minimal charges against them.[47]

FBI agent W. Mark Felt, along with Edward S. Miller, authorized FBI agents to break into homes secretly in 1972 and 1973, without a search warrant, on nine separate occasions. These kinds of FBI burglaries were known as "black bag jobs". The break-ins occurred at five addresses in New York and New Jersey, at the homes of relatives and acquaintances of Weather Underground members, and did not lead to the capture of any fugitives. The use of "black bag jobs" by the FBI was declared unconstitutional by the United States Supreme Court in the Plamondon case, 407 U.S. 297 (1972).

After revelation by the Church Committee of the FBI's illegal activities, many agents were investigated. Felt in 1976 publicly stated he had ordered break-ins and that individual agents were merely obeying orders and should not be punished for it. Felt also stated Gray also authorized the break-ins, but Gray denied this. Felt said on the CBS television program Face the Nation he would probably be a "scapegoat" for the Bureau's work.[48] "I think this is justified and I'd do it again tomorrow", he said on the program. While admitting the break-ins were "extralegal", he justified it as protecting the "greater good". Felt said:

To not take action against these people and know of a bombing in advance would simply be to stick your fingers in your ears and protect your eardrums when the explosion went off and then start the investigation.

The Attorney General in the new Carter administration, Griffin B. Bell, investigated, and on April 10, 1978, a federal grand jury charged Felt, Miller and Gray with conspiracy to violate the constitutional rights of American citizens by searching their homes without warrants, though Gray's case did not go to trial and was dropped by the government for lack of evidence on December 11, 1980.

The indictment charged violations of Title 18, Section 241 of the United States Code. The indictment charged Felt and the others

did unlawfully, willfully, and knowingly combine, conspire, confederate, and agree together and with each other to injure and oppress citizens of the United States who were relatives and acquaintances of the Weatherman fugitives, in the free exercise and enjoyments of certain rights and privileges secured to them by the Constitution and the laws of the United States of America.[49]

Felt and Miller attempted to plea bargain with the government, willing to agree to a misdemeanor guilty plea to conducting searches without warrants—a violation of 18 U.S.C. sec. 2236—but the government rejected the offer in 1979. After eight postponements, the case against Felt and Miller went to trial in the United States District Court for the District of Columbia on September 18, 1980.[50] On October 29, former President Richard M. Nixon appeared as a rebuttal witness for the defense, and testified that presidents since Franklin D. Roosevelt had authorized the bureau to engage in break-ins while conducting foreign intelligence and counterespionage investigations.[51] It was Nixon's first courtroom appearance since his resignation in 1974. Nixon also contributed money to Felt's legal defense fund, Felt's expenses running over $600,000. Also testifying were former Attorneys General Herbert Brownell, Jr., Nicholas deB. Katzenbach, Ramsey Clark, John N. Mitchell, and Richard G. Kleindienst, all of whom said warrantless searches in national security matters were commonplace and not understood to be illegal, but Mitchell and Kleindienst denied they had authorized any of the break-ins at issue in the trial.

The jury returned guilty verdicts on November 6, 1980. Although the charge carried a maximum sentence of 10 years in prison, Felt was fined $5,000. (Miller was fined $3,500).[52] Writing in The New York Times a week after the conviction, Roy Cohn claimed that Felt and Miller were being used as scapegoats by the Carter administration and that it was an unfair prosecution. Cohn wrote it was the "final dirty trick" and that there had been no "personal motive" to their actions.[53] The Times saluted the convictions saying it showed "the case has established that zeal is no excuse for violating the Constitution".[54] Felt and Miller appealed the verdict, and they were later pardoned by Ronald Reagan.[55]

Dissolution

Despite the change in their status the Weather Underground remained underground for a few more years. However, by 1976 the organization was disintegrating. The Weather Underground held a conference in Chicago called Hard Times. The idea was to create an umbrella organization for all radical groups. However, the event turned sour when Hispanic and Black groups accused the Weather Underground and the Prairie Fire Committee of limiting their roles in racial issues.[47] The conference enhanced a division within the Weather Underground. The Weather Underground faced accusations of abandonment of the revolution by reversing their original ideology.

East coast members favored a commitment to violence and challenged commitments of old leaders, Bernadine Dohrn, Bill Ayers and Jeff Jones. By the end of 1976, the Weather Underground would collapse.[56] Within two years, many members turned themselves in after taking advantage of President Jimmy Carter’s amnesty for draft dodgers.[17]

Mark Rudd turned himself in to authorities on January 20, 1978. Rudd was fined $4,000 and received two years probation.[17] Bernadine Dohrn and Bill Ayers turned themselves in on December 3, 1980, in New York, with substantial media coverage. Charges were dropped for Ayers. Dohrn received three years probation and a $15,000 fine.[17]

Certain members remained underground and joined other radical groups. Years after the dissolution of the WUO, former members Kathy Boudin, Judith Alice Clark, and David Gilbert formed the May 19 Communist Organization, which eventually joined with the Black Liberation Army. On October 20, 1981, in Nyack New York, the group attempted to rob a Brinks armored truck containing more than $1 million. The robbery turned violent, resulting in the murder of two police officers and a security guard.[17] Boudin, Clark, and Gilbert were found guilty and sentenced to lengthy terms in prison, considered the “last gasps” of the Weather Underground.[57]

Today

Widely-known members of the Weather Underground include Kathy Boudin, Mark Rudd, Terry Robbins, Ted Gold, Naomi Jaffe, Cathy Wilkerson, Jeff Jones, David Gilbert, Susan Stern, Bob Tomashevsky, Sam Karp, Russell Neufeld, Joe Kelly, Laura Whitehorn and the still-married couple Bernardine Dohrn and Bill Ayers. Most former Weathermen have successfully re-integrated into mainstream society, without necessarily repudiating their original intent.

Bill Ayers, now a professor of education at the University of Illinois at Chicago, was quoted in an interview to say "I don't regret setting bombs"[58] but has since claimed he was misquoted.[59] Brian Flanagan has expressed regret for his actions during the Weatherman years, and compared the group's activities to terrorism. Flanagan said: "When you feel that you have right on your side, you can do some pretty horrific things."[60] Mark Rudd, now a teacher of mathematics at Central New Mexico Community College, has said he has "mixed feelings" and feelings of "guilt and shame".

These are things I am not proud of, and I find it hard to speak publicly about them and to tease out what was right from what was wrong. I think that part of the Weatherman phenomenon that was right was our understanding of what the position of the United States is in the world. It was this knowledge that we just couldn't handle; it was too big. We didn't know what to do. In a way I still don't know what to do with this knowledge. I don't know what needs to be done now, and it's still eating away at me just as it did 30 years ago.

A non-violent faction of the Weather Underground continues today as the Prairie Fire Organizing Committee. Their official site reads:

- We oppose oppression in all its forms including racism, sexism, homophobia, classism and imperialism. We demand liberation and justice for all peoples. We recognize that we live in a capitalist system that favors a select few and oppresses the majority. This system cannot be reformed or voted out of office because reforms and elections do not challenge the fundamental causes of injustice.[61]

Weatherman documentaries

The WU insisted that Emile de Antonio shoot the documentary Underground in 1976. However, a much more extensive, widespread, and critically-acclaimed documentary emerged in 2002 with the Oscar-nominated The Weather Underground by filmmakers Bill Siegel and Sam Green. A little seen film called Ice had several WU members in a somewhat fictionalized revolutionary setting.

Chronology of events

This section needs additional citations for verification. (May 2008) |

- 18-22 June, 1969 – SDS National Convention held in Chicago, Illinois. Publication of "Weatherman" founding statement. Members seize control of SDS National Office.

- July, 1969 – Members Bernardine Dohrn, Eleanor Raskin, Dianne Donghi, Peter Clapp, David Millstone and Diana Oughton travel to Cuba and meet representatives of the North Vietnamese and Cuban governments.

- August 1969 – Weatherman member Linda Sue Evans travels to North Vietnam. Weatherman activists meet in Cleveland, Ohio, in preparation for "Days of Rage" protests scheduled for October, 1969 in Chicago.

- 4 September 1969 – Female members converge on South Hills High School in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, where they run through the school shouting anti-war slogans and distributing literature promoting the “National Action.” The term "Pittsburgh 26" refers to the 26 women arrested in connection with this incident.

- 24 September 1969 – A group of members confront Chicago Police during a demonstration supporting the "National Action," and protesting the commencement of the Chicago Eight trial stemming from the 1968 Democratic National Convention.

- 7 October 1969 – The Haymarket Police Statue in Chicago is bombed; The Weathermen later claim credit for the bombing in their book, Prairie Fire.

- 8 October-11, 1969 – The "Days of Rage" riots occur in Chicago, damaging a large amount of property. 287 Weatherman members are arrested, and some become fugitives when they fail to appear for trial in connection with their arrests.

- November-December, 1969 – A small number of Weatherman members join the first contingent of the Venceremos Brigade (VB) that departs for Cuba to harvest sugar cane.

- 6 December 1969 – Bombing of several Chicago Police cars parked in a precinct parking lot at 3600 North Halsted Street, Chicago. The WUO claims responsibility in Prairie Fire, stating it is a protest of the fatal police shooting of Illinois Black Panther Party leaders Fred Hampton and Mark Clark on 4 December 1969.

- 27 December-31, 1969 – The Weathermen hold a "War Council" in Flint, Michigan, where they finalize their plans to change into an underground organization that will commit strategic acts of sabotage against the government. Thereafter they are called the "Weather Underground Organization" (WUO).

- February, 1970 – The WUO closes the SDS National Office in Chicago, concluding the major campus-based organization of the 1960s. The first contingent of the VB returns from Cuba and the second contingent departs. By mid-February the bulk of the leading WUO members go underground.

- 13 February 1970 - Several police vehicles of the Berkeley, California, Police Department are bombed in the police parking lot; 16 February 1970: A bomb is detonated at the Golden Gate Park branch of the San Francisco Police Department, killing one officer and injuring a number of other policemen. No organization claims credit for either bombing.

- March, 1970 – Warrants are issued for several WUO members, who become federal fugitives when they fail to appear for trial in Chicago.

- 6 March 1970 – 34 sticks of dynamite are discovered in the 13th Police District of Detroit, Michigan. During February and early March, 1970, members of the WUO, led by Bill Ayers, are reported to be in Detroit, for the purpose of bombing a police facility.[citation needed]

- 6 March 1970 – WUO members Theodore Gold, Diana Oughton, and Terry Robbins are killed in the Greenwich Village townhouse explosion, when a nailbomb they were constructing detonates. The bomb was intended to be planted at a non-commissioned officer's dance at Fort Dix, New Jersey.

- 30 March 1970 – Chicago Police discover a WUO "bomb factory" on Chicago’s north side. A subsequent discovery of a WUO "weapons cache" in a south side Chicago apartment several days later ends WUO activity in the city.

- April, 1970 – The FBI arrests WUO members Linda Sue Evans and Dianne Donghi are arrested in New York.

- 2 April 1970 – A federal grand jury in Chicago returns a number of indictments charging WUO members with violation of federal anti-riot laws. Also, a number of additional federal warrants charging "unlawful flight to avoid prosecution" are returned in Chicago based on the failure of WUO members to appear for trial in local cases. (The Anti-riot Law charges were later dropped in January, 1974.)

- 10 May 1970 – The National Guard Association building in Washington, D.C. is bombed.[citation needed]

- 21 May 1970 – The WUO releases its "Declaration of a State of War" communique under Bernardine Dohrn's name.

- 6 June 1970 – In a letter, the WUO claims credit for bombing of the San Francisco Hall of Justice, although no explosion has occurred. Months later, workmen locate an unexploded bomb.[citation needed]

- 9 June 1970 - The New York City Police headquarters is bombed by Jane Alpert and accomplices. The Weathermen state this is in response to "police repression."[citation needed]

- 23 July 1970 – A federal grand jury in Detroit, Michigan, returns indictments against a number of underground WUO members and former WUO members charging violations of various explosives and firearms laws. (These indictments were later dropped in October, 1973.)

- 27 July 1970 - The United States Army base at The Presidio in San Francisco is bombed on the 11th anniversary of the Cuban Revolution. [NYT, 7/27/70]

- 12 September 1970 – The WUO helps Dr. Timothy Leary escape from the California Men's Colony prison.

- 8 October 1970 - Bombing of Marin County courthouse. WUO states this is in retaliation for the killings of Jonathan Jackson, William Christmas, and James McClain. [NYT, 8/10/70]

- 10 October 1970 - A Queens traffic-court building is bombed. WUO claims this is to express support for the New York prison riots. [NYT, 10/10/70, p. 12]

- 14 October 1970 - The Harvard Center for International Affairs is bombed. WUO claims this is to protest the war in Vietnam. [NYT, 10/14/70, p. 30]

- December, 1970 – Fugitive WUO member Caroline Tanker, who fled the country for Cuba, is arrested by the FBI in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Fugitive WUO member Judith Alice Clark is arrested by the FBI in New York.

- 1 March 1971 - The United States Capitol is bombed. WUO states this is to protest the invasion of Laos. President Richard M. Nixon denounces the bombing as a "shocking act of violence that will outrage all Americans." [NYT, 3/2/71]

- April, 1971 – FBI agents discover an abandoned WUO "bomb factory" in San Francisco, California.

- 29 August 1971 - Bombing of the Office of California Prisons, allegedly in retaliation for the killing of George Jackson. [LAT, 8/29/71]

- 17 September 1971 - The New York Department of Corrections in Albany, New York is bombed, as per the WUO to protest the killing of 29 inmates at Attica State Penitentiary. [NYT, 9/18/71]

- 15 October 1971 - The bombing of William Bundy's office in the MIT research center. [NYT, 10/16/71]

- 19 May 1972 - Bombing of The Pentagon, "in retaliation for the U.S. bombing raid in Hanoi." [NYT, 5/19/72]

- 18 May 1973 - The bombing of the 103rd Police Precinct in New York. WUO states this is in response to the killing of 10-year-old black youth Clifford Glover by police.

- 19 September 1973 – A WUO member is arrested by the FBI in New York. Released on bond, this member again submerges into the underground.

- 28 September 1973 - The ITT headquarters in New York and Rome, Italy are bombed. WUO states this is in response to ITT's alleged role in the Chilean coup earlier that month. [NYT, 9/28/73]

- 6 March 1974 - Bombing of the Dept. of Health, Education and Welfare offices in San Francisco. WUO states this is to protest alleged sterilization of poor women. In the accompanying communiqué, the Women’s Brigade argues for "the need for women to take control of daycare, healthcare, birth control and other aspects of women's daily lives."

- 31 May 1974 - The Office of the California Attorney General is bombed. WUO states this is in response to the killing of six members of the Symbionese Liberation Army.

- 17 June 1974 - Gulf Oil's Pittsburgh headquarters is bombed. WUO states this is to protest the company's actions in Angola, Vietnam, and elsewhere.

- July, 1974 – The WUO releases the book Prairie Fire, in which they indicate the need for a unified Communist Party. They encourage the creation of study groups to discuss their ideology, and continue to stress the need for violent acts. The book also admits WUO responsibility of several actions from previous years. The Prairie Fire Organizing Committee (PFOC) arises from the teachings in this book and is organized by many former WUO members.

- 11 September 1974 – Bombing of Anaconda Corporation (part of the Rockefeller Corporation). WUO states this is in retribution for Anaconda’s alleged involvement in the Chilean coup the previous year.

- 29 January 1975 - Bombing of the State Department; WUO states this is in response to escalation in Vietnam. (AP. "State Department Rattled by Blast," The Daily Times-News, January 29, 1975, p.1)

- March, 1975 – The WUO releases its first edition of a new magazine entitled Osawatomie.

- 16 June 1975 - Weathermen bomb a Banco de Ponce (a Puerto Rican bank) in New York, WUO states this is in solidarity with striking Puerto Rican cement workers.

- 11 July-13, 1975 – The PFOC holds its first national convention during which time they go through the formality of creating a new organization.

- September, 1975 – Bombing of the Kennecott Corporation; WUO states this is in retribution for Kennecott's alleged involvement in the Chilean coup two years prior.[62]

- October 20, 1981 - Brinks robbery in which Kathy Boudin and several members of the Weather Underground and the Black Liberation Army stole over $1 million from a Brinks armored car at the Nanuet Mall, near Nyack, New York on October 20, 1981. The robbers were stopped by police later that day and engaged them in a shootout, killing two police officers and one Brinks guard as well as wounding several others.

Members

- Diana Oughton

- Terry Robbins

- Kathy Boudin

- Mark Rudd

- Ted Gold

- Naomi Jaffe

- Cathy Wilkerson

- Jeff Jones (activist)

- Eleanor Raskin

- David Gilbert

- Susan Stern

- Bob Tomashevsky

- Sam Karp

- Russ Neufeld

- Joe Kelly (radical)

- Laura Whitehorn

- Bernardine Dohrn

- Bill Ayers

- Daniel Shakespeare

- Judith Clark

- Sam Melville

- Kit Bakke

- John Jacobs

- Brian Flanagan

- Mark Perry

See also

- The Weather Underground, documentary film

- Underground, documentary film

- Domestic terrorism in the United States

Further reading

- SDS: The Last Hurrah (DOCUMENT 4 of 5) chronicles the last tumultuous days of the original Students for a Democratic Society and the rise of the Revolutionary Youth Movement and the Worker Student Alliance as the two principal SDS factions. Document 5 of 5 is the program of the section of the RYM that would later adopt the name "Weatherman".

- Alan Adelson's, "SDS" remains the best history of the organization.

- Harold Jacobs, editor (1970). Weatherman. Ramparts Press.

- Osawatomie. Water Buffalo Print Collective. Journal of the Weather Underground Organization. Seattle. 1975. Osawatomie Issue #2 available on line. Retrieved July 27, 2005.

- Dan Berger (2006). Outlaws of America: The Weather Underground and the Politics of Solidarity. Oakland: AK Press.

- Jeremy Varon (2004). Bringing the War Home: The Weather Underground, the Red Army Faction, and Revolutionary Violence in the Sixties and Seventies. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-24119-3

- Ron Jacobs (1997). The way the wind blew: a history of the Weather Underground. London & New York: Verso. ISBN 1-85984-167-8

- Bill Ayers (2001). Fugitive Days. Boston: Beacon Press.

- Bernardine Dohrn, Bill Ayers. and Jeff Jones, editors (2006). Sing a Battle Song: The Revolutionary Poetry, Statements, and Communiqués of the Weather Underground, 1970-1974. New York: Seven Stories Press. ISBN 1-58322-726-1

- Cathy Wilkerson (2007). "Flying Close to the Sun," New York: Seven Story Press.

- Unger, Irwin. "The Movement A History of the American New Left, 1959-1972" New York: Dodd, Mead & Company, 1974.

References

- ^ a b c d Berger, Dan (2006). Outlaws of America: The Weather Underground and the Politics of Solidarity. AK Press. p. 95.

- ^ See document 5, Revolutionary Youth Movement (1969). ""You Don't Need a Weatherman to Know Which Way the Wind Blows."". Retrieved 2008-04-119.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ ""Weatherman"". Discoverthenetworks.org. Retrieved 2008-04-19.

- ^ Kushner, Harvey W. Encyclopedia of Terrorism. Thousand Oaks, Calif.: SAGE Publications, 2002. ISBN 0761924086

- ^ "Byte Out of History: 1975 Terrorism Flashback: State Department Bombing." Federal Bureau of Investigation. U.S. Department of Justice. January 29, 2004.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m The Weather Underground, produced by Carrie Lozano, directed by Bill Siegel and Sam Green, New Video Group, 2003, DVD.

- ^ a b ]All the rage | Features | guardian.co.uk Film

- ^ The Americans who declared war on their country | Features | guardian.co.uk Film

- ^ "BYTE OUT OF HISTORY / 1975 Terrorism Flashback: State Department Bombing / 01/29/04", Federal Bureau of Investigation website, retrieved June 8, 2008

- ^ Mehnert, Klaus, "Twilight of the Young, The Radical Movements of the 1960s and Their Legacy", Holt, Reinhart and Winston, 1977, page 47

- ^ Hamilton, Neil A., "Militias in America: A Reference Handbook", a volume in the "Contemporary World Issues" series, Santa Barbara, California, 1996, page 15; ISBN 0874368596; the book identifies its author this way: "Neil A. Hamilton is associate professor and chair of the history department at Spring Hill College in Mobile, Alabama"

- ^ No byline, UPI wire story, "Weathermen Got Name From Song: Groups Latest Designation Is Weather Underground", as published in The New York Times, January 30, 1975; "On Jan. 19, 1971, Bernardine Dohrn, a leading Weatherperson who has never been caught, issued a statement from hiding suggesting that the group was considering tactics other than bombing and terrorism.""; Montgomery, Paul L., "Guilty Plea Entered in 'Village' Bombing: Cathlyn Wilkerson Could Be Given Probation or Up to 7 Years", article, The New York Times, July 19, 1980: "the terrorist Weather Underground"

- ^ Web page titled, "BYTE OUT OF HISTORY: 1975 Terrorism Flashback: State Department Bombing", at F.B.I. website, dated January 29, 2004, retrieved September 2, 2008

- ^ Ayers, Bill, Fugitive Days, Beacon Press, ISBN 0807071242, p 263

- ^ Berger, Dan, Outlaws of America: The Weather Underground and the Politics of Solidarity, AK Press: Oakland, California, 2006, ISBN 1904859410 pp 286-287; the book describes Berger as "a writer, activist, and Ph.D. candidate", and the book is dedicated to his grandmother and to Weatherman member David Gilbert

- ^ Lader, Lawrence. Power on the Left. (New York City: W W Norton, 1979.) 192

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Jacobs, The Way the Wind Blew: A History of the Weather Underground, 1997.

- ^ a b c Avrich. The Haymarket Tragedy. pp. p. 431.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^ Adelman. Haymarket Revisited, p. 40.

- ^ a b c Jones, A Radical Line: From the Labor Movement to the Weather Underground, One Family's Century of Conscience, 2004.

- ^ a b Sale, SDS, 1973.

- ^ A Huey P. Newton Story - People - Other Players | PBS

- ^ American Experience | Eyes on the Prize | The Story of the Movement | PBS

- ^ Democracy Now! | Ex-Weather Underground Member Kathy Boudin Granted Parole

- ^ http://www.lapismagazine.org/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=110&Itemid=59

- ^ Former Weatherman Larry Grathwohl's October 18, 1974 testimony to the Senate Internal Security Subcommittee

- ^ http://www.sfpoa.org/journal/journals/20070201.pdf

- ^ a b KRON 4, "30-Y.O. Unsolved SF Murders Reopen", November 10, 2003

- ^ a b Zamora, Jim Herron, "Plaque honors slain police officer: Eight others injured in bomb attack that killed sergeant in 1970", The San Francisco Chronicle, February 17, 2007

- ^ a b Freddoso, David, The Case Against Barack Obama, Regnery Publishing, Inc., Washington, D.C., 2008, p 124; Chapter 7 Footnote 7: Hearings before the Subcommittee to Investigate the Administration of the Internal Security Act and Other Internal Security Laws of the Committee on the Judiciary, United States Senate, "Terroristic Activity Inside the Weatherman Movement, Part 2", October 18, 1974

- ^ Grathwohl, Larry, "as told to Frank Reagan", Bringing Down America: An FBI Informer with the Weathermen, Arlington House Publishers, New Rochelle, New York, 1976 pp 168, 169, ISBN 0870003350

- ^ http://article.nationalreview.com/print/?q=ODVlZTZlM2M5NTMxMzllMjJkODVkNzQ3YTFjMTY0NzE=

- ^ Fire in the Night |The Weathermen tried to kill my family | City Journal April 30, 2008

- ^ a b Wakin, Daniel J., [ "Quieter Lives for 60's Militants, but Intensity of Beliefs Hasn't Faded"], article The New York Times, August 24, 2003, retrieved June 7, 2008

- ^ 020510 michael frank's essay on 11th street

- ^ Kirkpatrick Sale, SDS, (New York: Random House, 1973), 611.

- ^ Harold Jacobs ed., Weatherman, (Ramparts Press, 1970), 508-511.

- ^ Harold Jacobs ed., Weatherman, (Ramparts Press, 1970), 374.

- ^ Kirkpatrick Sale, SDS, (New York: Random House, 1973), 648.

- ^ a b Jeremy Varon, Bringing The War Home: The Weather Underground, The Red Army Faction And Revolutionary Violence In The Sixties And Seventies, (Berkley: University of California Press, 2004), 292

- ^ Marty Jezer, Abbie Hoffman: American Rebel, (New Jersey: Rutgers University Press, 1992), 258-259.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

lfnyt112281was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ David Cunningham, There’s Something Happening Here: The New Left, The Klan, And FBI Counterintellegence, (Berkley: University of California Press, 2004), 33.

- ^ David Cunningham, There’s Something Happening Here: The New Left, The Klan, And FBI Counterintellegence, (Berkley: University of California Press, 2004), 35.

- ^ Paul Wolf, COINTELPRO, www.icdc.com/~paulwolf/cointelpro/cointel.htm

- ^ Nelson Blackstock, Cointelpro: The FBI’s Secret War on Political Freedom, (New York: Anchor Foundation, 1990), 185.

- ^ a b Jeremy Varon, Bringing The War Home: The Weather Underground, The Red Army Faction And Revolutionary Violence In The Sixties And Seventies, (Berkley: University of California Press, 2004), 297.

- ^ John Crewdson (August 30, 1976), "Ex-F.B.I. Aide Sees 'Scapegoat' Role", The New York Times, p. 21.

- ^ Felt, FBI Pyramid, p. 333.

- ^ Robert Pear: "Conspiracy Trial for 2 Ex-F.B.I. Officials Accused in Break-ins", The New York Times, September 19, 1980; & "Long Delayed Trial Over F.B.I. Break-ins to Start in Capital Tomorrow", The New York Times, September 14, 1980, p. 30.

- ^ Robert Pear, "Testimony by Nixon Heard in F.B.I. Trial", The New York Times, October 30, 1980.

- ^ Kessler, F.B.I.: Inside the Agency, p. 194.

- ^ Roy Cohn, "Stabbing the F.B.I.", The New York Times, November 15, 1980, p. 20.

- ^ "The Right Punishment for F.B.I. Crimes." (Editorial), The New York Times, December 18, 1980.

- ^ http://www.reagan.utexas.edu/archives/speeches/1981/41581d.htm

- ^ Jeremy Varon, Bringing The War Home: The Weather Underground, The Red Army Faction And Revolutionary Violence In The Sixties And Seventies, (Berkley: University of California Press, 2004), 297-298.

- ^ Richard G. Braungart and Margret M. Braungart, “From Protest to Terrorism: The Case of the SDS and The Weathermen.”, International Movement And Research: Social Movements and Violence: Participation in Underground Organizations, Volume 4, (Greenwich: Jai Press, 1992.), 67.

- ^ profile

- ^ Episodic Notoriety–Fact and Fantasy « Bill Ayers

- ^ FrontPage Magazine

- ^ Prairie Fire Organizing Committee: About Us

- ^ http://www.spunk.org/texts/misc/sp000209.txt

External links

- Vietnam era political protest site (UC Berkeley) - contains online audiorecordings, texts, and other media related to the Weather Underground

- The Weather Underground, a 2002 documentary directed and produced by Sam Green, Bill Siegel and Carrie Lozano

- FBI files: Weather Underground Organization (Weatherman). 420 pages. Retrieved June 3, 2005.

- The Weather Underground: A Look Back at the Antiwar Activists Who Met Violence with Violence. Guests: Mark Rudd, former member of the Weather Underground, Sam Green and Bill Siegel, documentary filmmakers/directors. Interviewers: Juan Gonzalez and Amy Goodman. Democracy Now!. Segment available via streaming real audio, or MP3 download. 1 hour 40 minutes. Thursday, 5 June 2003. Retrieved 20 May 2005.

- Jennifer Dohrn: I Was The Target Of Illegal FBI Break-Ins Ordered by Mark Felt aka "Deep Throat". Guest: Jennifer Dohrn. Interviewers: Juan Gonzalez and Amy Goodman. Segment available in transcript and via streaming real audio, 128k streaming real video or MP3 download. 29:32 minutes. Thursday, 2 June 2005. Retrieved 2 June 2005.

- Growing Up in the Weather Underground: A Father and Son Tell Their Story. Guests: Thai Jones and Jeff Jones. Interviewers: Juan Gonzalez and Amy Goodman. Democracy Now!. Segment available in transcript and via streaming real audio, 128k streaming Real Video or MP3 download. 17:01 minutes. Friday, 3 December 2004. Retrieved 20 May 2005.

- Full text of book The Way The Wind Blew, by Ron Jacobs (1997) about the Weather Underground Organization.

- Full text of book Weatherman, ed. by Harold Jacobs, a collection of documents by and about SDS/Weatherman. This book was published in 1970 and deals only with WUO's early period. Out of print.

- Prairie Fire Organizing Committee

- Wikipedia neutral point of view disputes from April 2008

- American communists

- Guerrilla organizations

- Clandestine groups

- Weather Underground

- COINTELPRO targets

- Defunct American political movements

- Far-left politics

- Terrorism in the United States

- Terrorist incidents in the 1970s

- 1969 establishments

- History of Chicago, Illinois

- Organizations designated as terrorist by the U.S. government

- Defunct organizations designated as terrorist