View model: Difference between revisions

→See also: Treasury Enterprise Architecture Framework |

→View model topics: intro about views |

||

| Line 33: | Line 33: | ||

In [[information system]]s, the traditional way to distinction between modeling perspectives is structural, functional and behavioral/processual perspectives. This together with rule, object, communication and actor and role perspectives is one way of classifying modeling approaches <ref>[http://www.idi.ntnu.no/~krogstie/publications/2003/quality-book/b2-languages.pdf Conceptual modeling], John Krogstie, 2003 </ref> |

In [[information system]]s, the traditional way to distinction between modeling perspectives is structural, functional and behavioral/processual perspectives. This together with rule, object, communication and actor and role perspectives is one way of classifying modeling approaches <ref>[http://www.idi.ntnu.no/~krogstie/publications/2003/quality-book/b2-languages.pdf Conceptual modeling], John Krogstie, 2003 </ref> |

||

== View == |

|||

A view allows a user to examine a portion of a particular interest area. For example, an Information View may present all functions, organizations, technology, etc. that use a particular piece of information, while the Organizational View may present all functions, technology, and information of concern to a particular organization. Views comprise a group of work products whose development requires a particular analytical and technical expertise because they focus on either the “what,” “how,” “who,” “where,” “when,” or “why” of the enterprise. For example, Functional View work products answer the question “how is the mission carried out?” They are most easily developed by experts in functional decomposition using process and activity modeling. They show the enterprise from the point of view of functions. They also may show organizational and information components, but only as they relate to functions.<ref name="TEAF00"> US Department of the Treasury Chief Information Officer Council (2000). [http://www.eaframeworks.com/TEAF/teaf.doc Treasury Enterprise Architecture Framework]. Version 1, July 2000.</ref> |

|||

=== Viewpoints === |

=== Viewpoints === |

||

Revision as of 13:49, 8 December 2008

A View model, or viewpoint model or viewpoints framework in systems engineering and software engineering is a framework, which defines the set of views or approaches to be used in systems analysis or the constructinon a an enterprise architecture.

Since the early 1990’s there have been a number of efforts to define standard approaches for describing and analyzing system architectures. Many of the recent Enterprise Architecture frameworks have some kind of set of views defined, but these sets are not always called "view models".

Overview

The purpose of viewpoints and views is to enable human engineers to comprehend very complex systems, and to organize the elements of the problem and the solution around domains of expertise. In the engineering of physically-intensive systems, viewpoints often correspond to capabilities and responsibilities within the engineering organization.[1]

Most complex system specifications are so extensive that no single individual can fully comprehend all aspects of the specifications. Furthermore, we all have different interests in a given system and different reasons for examining the system's specifications. A business executive will ask different questions of a system make-up than would a system implementer. The concept of viewpoints framework, therefore, is to provide separate viewpoints into the specification of a given complex system. These viewpoints each satisfy an audience with interest in a particular set of aspects of the system. Associated with each viewpoint is a viewpoint language that optimizes the vocabulary and presentation for the audience of that viewpoint. Viewpoint modeling has become an effective approach for dealing with the inherent complexity of large distributed systems.

Current software architectural practices, as described in IEEE Std. 1471, divide the design activity into several areas of concerns, each one focusing on a specific aspect of the system. Examples include the "4+1" view model, the Zachman framework, TOGAF, DoDAF and, RM-ODP.

History

Since the early 1990’s there have been a number of efforts to define standard approaches for describing and analyzing system architectures. Many of these have been funded by the United States Department of Defense, but some have sprung from international or national efforts in ISO or the IEEE. The most relevant of these, the IEEE Recommended Practice for Architectural Description of Software-Intensive Systems (IEEE-Std-1471-2000) provides some very useful definitions and guidelines for what a system architecture is and for the use of viewpoint specifications to address the stakeholder concerns.[2]

The IEEE 1471 specification describes the process for developing architecture descriptions under a number of scenarios, including precedented and unprecedented design, evolutionary design, and capture of design of existing systems. In all of these scenarios the overall process is the same: identify stakeholders, elicit concerns, identify a set of viewpoints to be used, and then apply these viewpoint specifications to develop a set of relevant views of the system. Although IEEE-1471 does mention the possibility of defining system, functional, and technical views (among others), it does not go so far as to define any specific set of views nor what these might be. Eventually in 1996 the ISO Reference Model for Open Distributed Processing (RM-ODP) was published to provide a useful framework for describing the architecture and design of large scale distributed systems.[2]

View model topics

Perspective

The idea of a view and viewpoints are close related to the idea of perspective. In science and society this term has multiple meaning. There are in fact different kind of perspectives. In context of vision and visual perception, a visual perspective is the way in which objects appear to the eye based on their spatial attributes, or their dimensions and the position of the eye relative to the objects.

In the graphic arts, such as drawing graphical perspective representing the effects of visual perspective in drawings. Here it is an approximate representation, on a flat surface such as paper, of an image as it is perceived by the eye. Perspective works by representing the light that passes from a scene through an imaginary rectangle (the painting), to the viewer's eye. It is similar to a viewer looking through a window and painting what is seen directly onto the windowpane. Each painted object in the scene is a flat, scaled down version of the object on the other side of the window.[3]

In the cognitive science the term "perspective" is used more metaphorically. In theory of cognition a cognitive perspective is the choice of a context or a reference (or the result of this choice) from which to sense, categorize, measure or codify experience, cohesively forming a coherent belief, typically for comparing with another, in relation to cognitive topics.

Cartography speaks of map projection, meaning any method of representing the surface of a sphere or other shape on a plane. Map projections are necessary for creating maps. All map projections distort the surface in some fashion. Depending on the purpose of the map, some distortions are acceptable and others are not; therefore different map projections exist in order to preserve some properties of the sphere-like body at the expense of other properties. There is no limit to the number of possible map projections.

The views used in systems and software engineering have some similarity with the visual perspective used in drawing and the map projection in cartography. As in map projection the Systems analyst has the possibility to use different kind of views to construct different kind of images of the system. There also seems to be no limit to the number of possible views. The difference is that in drawing and mapmaking a physical objects and physical space is represented. Systems and software engineering are dealing with representing societal and knowledge structures. Creating systems views has also similarity with the cognitive perspective. There is choice of a context or a reference from which experience codified and categorized often within modelling frameworks.

Modeling perspectives

Modeling perspectives is a set of different ways to represent pre-selected aspects of a system. Each perspective has a different focus, conceptualization, dedication and visualization of what the model is representing.

In information systems, the traditional way to distinction between modeling perspectives is structural, functional and behavioral/processual perspectives. This together with rule, object, communication and actor and role perspectives is one way of classifying modeling approaches [4]

View

A view allows a user to examine a portion of a particular interest area. For example, an Information View may present all functions, organizations, technology, etc. that use a particular piece of information, while the Organizational View may present all functions, technology, and information of concern to a particular organization. Views comprise a group of work products whose development requires a particular analytical and technical expertise because they focus on either the “what,” “how,” “who,” “where,” “when,” or “why” of the enterprise. For example, Functional View work products answer the question “how is the mission carried out?” They are most easily developed by experts in functional decomposition using process and activity modeling. They show the enterprise from the point of view of functions. They also may show organizational and information components, but only as they relate to functions.[5]

Viewpoints

Viewpoint is a systems engineering concept that describes a partitioning of concerns in the characterization of a system. A viewpoint is an abstraction that yields a specification of the whole system restricted to a particular set of concerns[6]. Adoption of a viewpoint is useful in separating and resolving a set of engineering concerns involved in integrating a set of components into a system. Adopting a viewpoint makes certain aspects of the system "visible" and focuses attention on them, while making other aspects "invisible," so that issues in those aspects can be addressed separately. A good selection of viewpoints also partitions the design of the system into specific areas of expertise. [1]

Viewpoints provide the conventions, rules, and languages for constructing views. A view is a representation of a whole system from the perspective of a related set of concerns. Views are themselves modular and well formed, and each view is usually intended to correspond to exactly one viewpoint. A view may consist of one or more architectural models.[7] Each such architectural model is developed using the methods established by its associated architectural viewpoint. An architectural model may participate in more than one view. In a complex system, ADs may be developed for components of the system, as well as for the system as a whole.[2]

Viewpoint model

In any given viewpoint, it is possible to make a model of the system that contains only the objects that are visible from that viewpoint, but also captures all of the objects, relationships and constraints that are present in the system and relevant to that viewpoint. Such a model is said to be a viewpoint model, or a view of the system from that viewpoint.[1]

A given view is a specification for the system at a particular level of abstraction from a given viewpoint. Different levels of abstraction contain different levels of detail. Higher-level views allow the engineer to fashion and comprehend the whole design and identify and resolve problems in the large. Lower-level views allow the engineer to concentrate on a part of the design and develop the detailed specifications.[1]

In the system itself, however, all of the specifications appearing in the various viewpoint models must be addressed in the realized components of the system. And the specifications for any given component may be drawn from many different viewpoints. On the other hand, the specifications induced by the distribution of functions over specific components and component interactions will typically reflect a different partitioning of concerns than that reflected in the original viewpoints. Thus additional viewpoints, addressing the concerns of the individual components and the bottom-up synthesis of the system, may also be useful.[1]

Enterprise Architecture Framework

Enterprise Architecture framework defines how to organize the structure and views associated with an Enterprise Architecture. Because the discipline of Enterprise Architecture and Engineering is so broad, and because enterprises can be large and complex, the models associated with the discipline also tend to be large and complex. To manage this scale and complexity, an Architecture Framework provides tools and methods that can bring the task into focus and allow valuable artifacts to be produced when they are most needed.

Architecture Frameworks are commonly used in Information technology and Information system governance. An organization may wish to mandate that certain models be produced before a system design can be approved. Similarly, they may wish to specify certain views be used in the documentation of procured systems - the U.S. Department of Defense stipulates that specific DoDAF views be provided by equipment suppliers for capital project above a certain value.

Types of view models

Three schema approach

The Three schema approach for data modeling can be considered one of the first view models. It is an approach to building information systems and systems information management, that promotes the conceptual model as the key to achieving data integration.[9] The Three schema approach defines three schema's and views:

- External schema for user views

- Conceptual schema integrates external schemata

- Internal schema that defines physical storage structures

At the center, the conceptual schema defines the ontology of the concepts as the users think of them and talk about them. The physical schema describes the internal formats of the data stored in the database, and the external schema defines the view of the data presented to the application programs.[10] The framework attempted to permit multiple data models to be used for external schemata.[11]

Over the years, the skill and interest in building information systems has grown tremendously. However, for the most part, the traditional approach to building systems has only focused on defining data from two distinct views, the "user view" and the "computer view". From the user view, which will be referred to as the “external schema,” the definition of data is in the context of reports and screens designed to aid individuals in doing their specific jobs. The required structure of data from a usage view changes with the business environment and the individual preferences of the user. From the computer view, which will be referred to as the “internal schema,” data is defined in terms of file structures for storage and retrieval. The required structure of data for computer storage depends upon the specific computer technology employed and the need for efficient processing of data.[12]

4+1

4+1 is a view model designed by Philippe Kruchten in 1995 for describing the architecture of software-intensive systems, based on the use of multiple, concurrent views. The views are used to describe the system in the viewpoint of different stakeholders, such as end-users, developers and project managers. The four views of the model are logical, development, process and physical view. In addition selected use cases or scenarios are utilized to illustrate the architecture. Hence the model contains 4+1 views.[13]

RM-ODP

The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) Reference Model for Open Distributed Processing (RM-ODP) [14] specifies a set of viewpoints for partitioning the design of a distributed software/hardware system. Since most integration problems arise in the design of such systems or in very analogous situations, these viewpoints may prove useful in separating integration concerns. The RMODP viewpoints are:[1]

- the enterprise viewpoint, which is concerned with the purpose and behaviors of the system as it relates to the business objective and the business processes of the organization

- the information viewpoint, which is concerned with the nature of the information handled by the system and constraints on the use and interpretation of that information

- the computational viewpoint, which is concerned with the functional decomposition of the system into a set of components that exhibit specific behaviors and interact at interfaces

- the engineering viewpoint, which is concerned with the mechanisms and functions required to support the interactions of the computational components

- the technology viewpoint, which is concerned with the explicit choice of technologies for the implementation of the system, and particularly for the communications among the components

RMODP further defines a requirement for a design to contain specifications of consistency between viewpoints, including[1]:

- the use of enterprise objects and processes in defining information units

- the use of enterprise objects and behaviors in specifying the behaviors of computational components, and use of the information units in defining computational interfaces

- the association of engineering choices with computational interfaces and behavior requirements

- the satisfaction of information, computational and engineering requirements in the chosen technologies

DoDAF

The Department of Defense Architecture Framework (DoDAF) defines a standard way to organize an enterprise architecture (EA) or systems architecture into complementary and consistent views. It is especially suited to large systems with complex integration and interoperability challenges, and is apparently unique in its use of "operational views" detailing the external customer's operating domain in which the developing system will operate.

The DoDAF defines a set of products that act as mechanisms for visualizing, understanding, and assimilating the broad scope and complexities of an architecture description through graphic, tabular, or textual means. These products are organized under four views:

- Overarching All View (AV),

- Operational View (OV),

- Systems View (SV), and the

- Technical Standards View (TV).

Each view depicts certain perspectives of an architecture as described below. Only a subset of the full DoDAF viewset is usually created for each system development. The figure represents the information that links the operational view, systems and services view, and technical standards view. The three views and their interrelationships driven – by common architecture data elements – provide the basis for deriving measures such as interoperability or performance, and for measuring the impact of the values of these metrics on operational mission and task effectiveness.[15]

Federal Enterprise Architecture

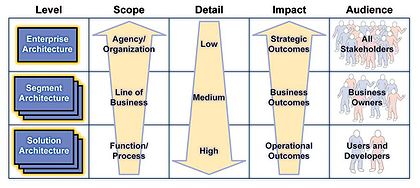

In the US Federal Enterprise Architecture enterprise, segment, and solution architecture provide different business perspectives by varying the level of detail and addressing related but distinct concerns. Just as enterprises are themselves hierarchically organized, so are the different views provided by each type of architecture. The Federal Enterprise Architecture Practice Guidance (2006) has defined three types of architecture:[16]

- Enterprise architecture,

- Segment architecture, and

- Solution architecture.

By definition, Enterprise Architecture (EA) is fundamentally concerned with identifying common or shared assets – whether they are strategies, business processes, investments, data, systems, or technologies. EA is driven by strategy; it helps an agency identify whether its resources are properly aligned to the agency mission and strategic goals and objectives. From an investment perspective, EA is used to drive decisions about the IT investment portfolio as a whole. Consequently, the primary stakeholders of the EA are the senior managers and executives tasked with ensuring the agency fulfills its mission as effectively and efficiently as possible. [16]

By contrast, segment architecture defines a simple roadmap for a core mission area, business service, or enterprise service. Segment architecture is driven by business management and delivers products that improve the delivery of services to citizens and agency staff. From an investment perspective, segment architecture drives decisions for a business case or group of business cases supporting a core mission area or common or shared service. The primary stakeholders for segment architecture are business owners and managers. Segment architecture is related to EA through three principles: structure, reuse, and alignment. First, segment architecture inherits the framework used by the EA, although it may be extended and specialized to meet the specific needs of a core mission area or common or shared service. Second, segment architecture reuses important assets defined at the enterprise level including: data; common business processes and investments; and applications and technologies. Third, segment architecture aligns with elements defined at the enterprise level, such as business strategies, mandates, standards, and performance measures.[16]

Nominal set of views

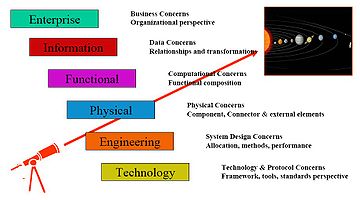

In search of "Framework for Modeling Space Systems Architectures" Peter Shames and Joseph Skipper (2006) defined a "nominal set of views"[2], Derived from CCSDS RASDS, RM-ODP, ISO 10746 and compliant with IEEE 1471.

This "set of views", as described below, is a listing of possible modeling viewpoints. Not all of these views may be used for any one project and other views may be defined as necessary. Note that for some analyses elements from multiple viewpoints may be combined into a new view, possibly using a layered representation.

In a latter presentation this nominal set of views was presented as an Extended RASDS Semantic Information Model Derivation.[17] Hereby RASDS stands for Reference Architecture for Space Data Systems. see second image.

- Enterprise Viewpoint[2]

- Organization view – Includes organizational elements and their structures and relationships. May include agreements, contracts, policies and organizational interactions.

- Requirements view – Describes the requirements, goals, and objectives that drive the system. Says what the system must be able to do.

- Scenario view – Describes the way that the system is intended to be used, see scenario planning. Includes user views and descriptions of how the system is expected to behave.

- Information viewpoint[2]

- Metamodel view – An abstract view that defines information model elements and their structures and relationships. Defines the classes of data that are created and managed by the system and the data architecture.

- Information view – Describes the actual data and information as it is realized and manipulated within the system. Data elements are defined by the metamodel view and they are referred to by functional objects in other views.

- Functional viewpoint[2]

- Functional Dataflow view – An abstract view that describes the functional elements in the system, their interactions, behavior, provided services, constraints and data flows among them. Defines which functions the system is capable of performing, regardless of how these functions are actually implemented.

- Functional Control view – Describes the control flows and interactions among functional elements within the system. Includes overall system control interactions, interactions between control elements and sensor / effector elements and management interactions.

- Physical viewpoint[2]

- Data System view – Describes instruments, computers, and data storage components, their data system attributes and the communications connectors (busses, networks, point to point links) that are used in the system.

- Telecomm view – Describes the telecomm components (antenna, transceiver), their attributes and their connectors (RF or optical links).

- Navigation view – Describes the motion of the major elements within the system (trajectory, path, orbit), including their interaction with external elements and forces that are outside of the control of the system, but that must be modeled with it to understand system behavior (planets, asteroids, solar pressure, gravity)

- Structural view – Describes the structural components in the system (s/c bus, struts, panels, articulation), their physical attributes and connectors, along with the relevant structural aspects of other components (mass, stiffness, attachment)

- Thermal view – Describes the active and passive thermal components in the system (radiators, coolers, vents) and their connectors (physical and free space radiation) and attributes, along with the thermal properties of other components (i.e. antenna as sun shade)

- Power view – Describes the active and passive power components in the system (solar panels, batteries, RTGs) within the system and their connectors, along with the power properties of other components (data system and propulsion elements as power sinks and structural panels as grounding plane)

- Propulsion view – Describes the active and passive propulsion components in the system (thrusters, gyros, motors, wheels) within the system and their connectors, along with the propulsive properties of other components

- Engineering viewpoint[2]

- Allocation view – Describes the allocation of functional objects to engineered physical and computational components within the system, permits analysis of performance and used to verify satisfaction of requirements

- Software view - Describes the software engineering aspects of the system, software design and implementation of functionality within software components, select languages and libraries to be used, define APIs, do the engineering of abstract functional objects into tangible software elements. Some functional elements, described using a software language, may actually be implemented as hardware (FPGA, ASIC)

- Hardware views – Describes the hardware engineering aspects of the system, hardware design, selection and implementation of all of the physical components to be assembled into the system. There may be many of these views, each specific to a different engineering discipline.

- Communications Protocol view – Describes the end to end design of the communications protocols and related data transport and data management services, shows the protocol stacks as they are implemented on each of the physical components of the system.

- Risk view – Describes the risks associated with the system design, processes, and technologies, assigns additional risk assessment attributes to other elements described in the architecture

- Control Engineering view - Analyzes system from the perspective of its controllability, allocation of elements into system under control and control system

- Integration and Test view – Looks at the system from the perspective of what must be done to assemble, integrate and test system and sub-systems, and assemblies. Includes verification of proper functionality, driven by scenarios, in satisfaction of requirements.

- IV&V view – independent validation and verification of functionality and proper operation of the system in satisfaction of requirements. Does system as designed and developed meet goals and objectives.

- Technology viewpoint[2]

- Standards view – Defines the standards to be adopted during design of the system (e.g. communication protocols, radiation tolerance, soldering). These are essentially constraints on the design and implementation processes.

- Infrastructure view – Defines the infrastructure elements that are to support the engineering, design, and fabrication process. May include data system elements (design repositories, frameworks, tools, networks) and hardware elements (chip fabrication, thermal vacuum facility, machine shop, RF testing lab)

- Technology Development & Assessment view – Includes description of technology development programs designed to produce algorithms or components that may be included in a system development project. Includes evaluation of properties of selected hardware and software components to determine if they are at a sufficient state of maturity to be adopted for the mission being designed.

In contrast to the previous listed view models, this "nominal set of views" lists a whole range of views, possible to develop powerful and extensible approaches for describing a general class of software intensive system architectures.[2]

See also

- Enterprise Architecture framework

- Organizational architecture

- Software development methodology

- Treasury Enterprise Architecture Framework

- TOGAF

- Zachman framework

References

![]() This article incorporates public domain material from the National Institute of Standards and Technology

This article incorporates public domain material from the National Institute of Standards and Technology

- ^ a b c d e f g Edward J. Barkmeyer ea (2003). Concepts for Automating Systems Integration NIST 2003.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Peter Shames, Joseph Skipper. "Toward a Framework for Modeling Space Systems Architectures". NASA, JPL.

- ^ Perspective Drawing Handbook By Joseph D'Amelio, p. 19, published by Dover Publications

- ^ Conceptual modeling, John Krogstie, 2003

- ^ US Department of the Treasury Chief Information Officer Council (2000). Treasury Enterprise Architecture Framework. Version 1, July 2000.

- ^ IEEE-Std-1471-2000 Recommended Practice for Architectural Descriptions for Software-Intensive Systems, Institute for Electrical and Electronics Engineering, New York, NY, 2000.

- ^ IEEE-1471-2000

- ^ Matthew West and Julian Fowler (1999). Developing High Quality Data Models. The European Process Industries STEP Technical Liaison Executive (EPISTLE).

- ^ STRAP SECTION 2 APPROACH. Retrieved 30 September 2008.

- ^ John F. Sowa (2004). [ "The Challenge of Knowledge Soup"]. published in: Research Trends in Science, Technology and Mathematics Education. Edited by J. Ramadas & S. Chunawala, Homi Bhabha Centre, Mumbai, 2006.

- ^ Gad Ariav & James Clifford (1986). New Directions for Database Systems: Revised Versions of the Papers. New York University Graduate School of Business Administration. Center for Research on Information Systems, 1986.

- ^ itl.nist.gov (1993) Integration Definition for Information Modeling (IDEFIX). 21 Dec 1993.

- ^ Kruchten, Philippe (1995, November). "Architectural Blueprints : The “4+1” View Model of Software Architecture". In: IEEE Software 12 (6), pp. 42-50.

- ^ ISO/IEC 10746-1:1998 Information technology – Open Distributed Processing: Reference Model – Part 1: Overview, International Organization for Standardization, Geneva, Switzerland, 1998.

- ^ a b DoD (2007) DoD Architecture Framework Version 1.5. 23 April 2007

- ^ a b c d Federal Enterprise Architecture Program Management Office (2006). FEA Practice Guidance.

- ^ a b c Peter Shames & Joseph Skipper (2006). Towards a Framework for Modeling Space Systems Architectures. 25 May 2006.