Frida Kahlo: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

rv cut-and-paste from http://www.artchive.com/artchive/K/kahlo.html |

||

| Line 41: | Line 41: | ||

'''Magdalena Carmen Frida Kahlo y Calderón''' (as her name appears on her [[birth certificate]]<ref name=herrera>{{cite book | last = Herrera | first = Hayden | authorlink = Hayden Herrera | title = A Biography of Frida Kahlo | publisher = HarperCollins | year= 1983 | location = New York | id = ISBN-13: 978-0060085896}}</ref>) was born on July 6, 1907 in the house of her parents, known as ''La Casa Azul'' (The Blue House), in [[Coyoacán]]. At the time, this was a small town on the outskirts of [[Mexico City]]. |

'''Magdalena Carmen Frida Kahlo y Calderón''' (as her name appears on her [[birth certificate]]<ref name=herrera>{{cite book | last = Herrera | first = Hayden | authorlink = Hayden Herrera | title = A Biography of Frida Kahlo | publisher = HarperCollins | year= 1983 | location = New York | id = ISBN-13: 978-0060085896}}</ref>) was born on July 6, 1907 in the house of her parents, known as ''La Casa Azul'' (The Blue House), in [[Coyoacán]]. At the time, this was a small town on the outskirts of [[Mexico City]]. |

||

Her father, [[Guillermo Kahlo]] (1872-1941), was born Carl Wilhelm Kahlo in [[Pforzheim]], [[Germany]]. He was the son of the [[Painting|painter]] and [[goldsmith]] Jakob Heinrich Kahlo and Henriett E. Kaufmann. Kahlo claimed her father was of [[Jewish]] and [[Hungarians|Hungarian]] ancestry,<ref name="Frida Kahlo (1907-1954), Mexican Painter">{{cite web | title=Frida Kahlo (1907-1954), Mexican Painter | work=Biography, www.fridakahlo.com | url=http://www.fridakahlo.com/bio.shtml | accessdate=2007-06-02}}</ref> but a 2005 book on Guillermo Kahlo, ''Fridas Vater'' (Schirmer/Mosel, 2005), states that he was descended from a long line of German [[Lutheran]]s.<ref>[http://www.jpost.com/servlet/Satellite?cid=1143498883340&pagename=JPost%2FJPArticle%2FShowFull Frida Kahlo's father wasn't Jewish after all], Meir Ronnen, April 20, 2006, "Books", ''[[Jerusalem Post]]''</ref> Wilhelm Kahlo sailed to Mexico in 1891 at the age of nineteen and, upon his arrival, changed his German forename, Wilhelm, to its [[Spanish language|Spanish]] equivalent, 'Guillermo'. During the late 1930s, in the face of rising [[Nazism]] in Germany, Frida acknowledged and asserted her German heritage by spelling her name, '''Frieda''' (an allusion to "Frieden", which means "peace" in German). |

|||

"In 1953, when Frida Kahlo had her first solo exhibition in Mexico (the only one held in her native country during her lifetime), a local critic wrote: 'It is impossible to separate the life and work of this extraordinary person. Her paintings are her biography.' This observation serves to explain both why her work is so different from that of her contemporaries, the Mexican Muralists, and why she has since become a feminist icon. |

|||

"Kahlo was born in Mexico City in 1907, the third daughter of Guillermo and Matilda Kahlo. Her father was a photographer of Hungarian Jewish descent, who had been born in Germany; her mother was Spanish and Native American. Her life was to be a long series of physical traumas, and the first of these came early. At the age of six she was stricken with polio, which left her with a limp. In childhood, she was nevertheless a fearless tomboy, and this made Frida her father's favourite. He had advanced ideas about her education, and in 1922 she entered the Preparatoria (National Preparatory School), the most prestigious educational institution in Mexico, which had only just begun to admit girls. She was one of only thirty-five girls out of two thousand students. |

|||

Frida's mother, Matilde Calderón y Gonzalez, was a devout Catholic of primarily [[indigenous peoples of the Americas|indigenous]], as well as [[Spanish people|Spanish]] descent.<ref name="Frida Kahlo (1907-1954), Mexican Painter"/> Frida's parents were married shortly after the death of Guillermo's first wife during the birth of her second child. Although their marriage was quite unhappy, Guillermo and Matilde had four daughters, with Frida being the third. She had two older half sisters. Frida once remarked that she grew up in a world surrounded by females. Throughout most of her life, however, Frida remained close to her father. |

|||

"It was there that she met her husband-to-be, Diego Rivera, who had recently returned home from France, and who had been commissioned to paint a mural there. Kahlo was attracted to him, and not knowing quite how to deal with the emotions she felt, expressed them by teasing him, playing practical jokes, and by trying to excite the jealousy of the painter's wife, Lupe Marin. |

|||

The [[Mexican Revolution]] began in 1910 when Kahlo was three years old. Later, however, Kahlo claimed that she was born in 1910 so people would directly associate her with the revolution. In her writings, she recalled that her mother would usher her and her sisters inside the house as gunfire echoed in the streets of her hometown, which was extremely poor at the time. Occasionally, men would leap over the walls into their backyard and sometimes her mother would prepare a meal for the hungry revolutionaries. |

|||

"In 1925, Kahlo suffered the serious accident which was to set the pattern for much of the rest of her life. She was travelling in a bus which collided with a tramcar, and suffered serious injuries to her right leg and pelvis. The accident made it impossible for her to have children, though it was to be many years before she accepted this. It also meant that she faced a life-long battle against pain. In 1926, during her convalescence, she painted her first self-portrait, the beginning of a long series in which she charted the events of her life and her emotional reactions to them. |

|||

Kahlo contracted [[polio]] at age six, which left her right leg thinner than the left, which Kahlo disguised by wearing long skirts. It has been conjectured that she also suffered from [[spina bifida]], a congenital disease that could have affected both spinal and leg development.<ref name=Budrys>{{cite journal | last = Budrys | first = Valmantas | title = Neurological Deficits in the Life and Work of Frida Kahlo | journal = European Neurology | volume = 55 | issue = 1 | month = February | year = 2006 | issn = 0014-3022 (print), ISSN = 1421-9913 (Online) | url = http://content.karger.com/produktedb/produkte.asp?typ=fulltext&file=ENE2006055001004 | accessdate = 2008-01-22}}</ref> As a girl, she participated in [[boxing]] and other sports. In 1922, Kahlo was enrolled in the Preparatoria, one of Mexico's premier schools, where she was one of only thirty-five girls. Kahlo joined a [[clique]] at the school and fell in love with the leader, Alejandro Gomez Arias. During this period, Kahlo also witnessed violent armed struggles in the streets of [[Mexico City]] as the [[Mexican Revolution]] continued. |

|||

On September 17, 1925, Kahlo was riding in a bus when the vehicle collided with a trolley car. She suffered serious injuries in the accident, including a broken [[spinal column]], a broken [[collarbone]], broken [[ribs]], a broken [[pelvis]], eleven fractures in her right [[leg]], a crushed and dislocated right foot, and a dislocated shoulder. An iron handrail pierced her abdomen and her [[uterus]], which seriously damaged her reproductive ability. |

|||

"She met Rivera again in 1928, through her friendship with the photographer and revolutionary Tina Modotti. Rivera's marriage had just disintegrated, and the two found that they had much in common, not least from a political point of view, since both were now communist militants. They married in August 1929. Kahlo was later to say: 'I suffered two grave accidents in my life. One in which a streetcar knocked me down... The other accident is Diego.' |

|||

Although she recovered from her injuries and eventually regained her ability to walk, she was plagued by [[relapse]]s of extreme pain for the remainder of her life. The pain was intense and often left her confined to a [[hospital]] or bedridden for months at a time. She underwent as many as thirty-five operations as a result of the accident, mainly on her back, her right leg and her right foot. |

|||

"The political climate in Mexico was deteriorating for those with left-wing sympathies, thanks to the reactionary Calles government, and the mural-painting programme initiated by the great Minister of Education Jose Vasconcelos had ground to a halt. But Rivera's artistic reputation was expanding rapidly in the United States. In 1930, the couple left for San Francisco; then, after a brief return to Mexico, they went to New York in 1931 for the Rivera retrospective organized by the Museum of Modern Art. Kahlo, at this stage, was regarded chiefly as a charming appendage to a famous husband, but the situation was soon to change. In 1932 Rivera was commissioned to paint a major series of murals for the Detroit Museum, and here Kahlo suffered a miscarriage. While recovering, she painted Miscarriage in Detroit, the first of her truly penetrating self-portraits. The style she evolved was entirely unlike that of her husband, being based on Mexican folk art and in particular on the small votive pictures known as retablos, which the pious dedicated in Mexican churches. Rivera's reaction to his wife's work was, however, both perceptive and generous: |

|||

==Career as painter== |

|||

Frida began work on a series of masterpieces which had no precedent in the history of art - paintings which exalted the feminine quality of truth, reality, cruelty and suffering. Never before had a woman put such agonized poetry on canvas as Frida did at this time in Detroit. |

|||

[[Image:Frida Kahlo Diego Rivera 1932.jpg|thumb|left|Frida Kahlo with [[Diego Rivera]] in 1932, by [[Carl Van Vechten]]]] |

|||

"Kahlo, however, pretended not to consider her work important. As her biographer Hayden Herrera notes, 'she preferred to be seen as a beguiling personality rather than as a painter.' From Detroit they went once again to New York, where Rivera had been commissioned to paint a mural in the Rockefeller Center. The commission erupted into an enormous scandal, when the patron ordered the half-completed work destroyed because of the political imagery Rivera insisted on including. But Rivera lingered in the United States, which he loved and Kahlo now loathed. When they finally returned to Mexico in 1935, Rivera embarked on an affair with Kahlo's younger sister Cristina. Though they finally made up their quarrel, this incident marked a turning point in their relationship. Rivera had never been faithful to any woman; Kahlo now embarked on a series of affairs with both men and women which were to continue for the rest of her life. Rivera tolerated her lesbian relationships better than he did the heterosexual ones, which made him violently jealous. One of Kahlo's more serious early love affairs was with the Russian revolutionary leader Leon Trotsky, now being hounded by his triumphant rival Stalin, and who had been offered refuge in Mexico in 1937 on Rivera's initiative. Another visitor to Mexico at this time, one who would gladly have had a love affair with Kahlo but for the fact that she was not attracted to him, was the leading figure of the Surrealist Group, André Breton. Breton arrived in 1938 and was enchanted with Mexico, which he found to be a 'naturally surrealist' country, and with Kahlo's painting. Partly through his initiative, she was offered a show at the fashionable Julian Levy Gallery in New York later in 1938, and Breton himself wrote a rhetorical catalogue preface. The show was a triumph, and about half the paintings were sold. In 1939, Breton suggested a show in Paris, and offered to arrange it. Kahlo, who spoke no French, arrived in France to find that Breton had not even bothered to get her work out of customs. |

|||

After the accident, Kahlo turned her attention away from the study of medicine to begin a full-time painting career. The accident left her in a great deal of pain while she recovered in a full body cast; she painted to occupy her time during her temporary state of immobilization. Her self-portraits became a dominant part of her life when she was immobile for three months after her accident. Kahlo once said, "I paint myself because I am often alone and I am the subject I know best." Her mother had a special easel made for her so she could paint in bed, and her father lent her his box of oil paints and some brushes.<ref>{{cite book | last = Cruz | first = Barbara | authorlink = Barbara Cruz | title = Frida Kahlo: Portrait of a Mexican Painter | publisher = Enslow | year= 1996 | location = Berkeley Heights | pages = 9 | id = ISBN-13: 0-89490-765-4}}</ref> |

|||

"The enterprise was finally rescued by Marcel Duchamp, and the show opened about six weeks late. It was not a financial success, but the reviews were good, and the Louvre bought a picture for the Jeu de Paume. Kahlo also won praise from Kandinsky and Picasso. She had, however, conceived a violent dislike for what she called 'this bunch of coocoo lunatic sons of bitches of surrealists.' She did not renounce Surrealism immediately. in January 1940, for example, she was a participant (with Rivera) in the International Exhibition of Surrealism held in Mexico City. Later, she was to be vehement in her denials that she had ever been a true Surrealist. 'They thought I was a Surrealist,' she said, 'but I wasn't. I never painted dreams. I painted my own reality.' |

|||

Drawing on personal experiences, including her marriage, her [[miscarriage]]s, and her numerous operations, Kahlo's works often are characterized by their stark portrayals of pain. Of her 143 paintings, 55 are self-portraits which often incorporate symbolic portrayals of physical and psychological wounds. She insisted, "I never painted dreams. I painted my own reality." |

|||

"Early in 1940, for motives which are still somewhat mysterious, Kahlo and Rivera divorced, though they continued to make public appearances together. In May, after the first attempt on Trotsky's life, led by the painter Siqueiros, Rivera thought it prudent to leave for San Francisco. After the second, and successful attempt, Kahlo, who had been a friend of Trotsky's assassin, was questioned by the police. She decided to leave Mexico for a while, and in September she joined her ex-husband. Less than two months later, while they were still in the United States, they remarried. One reason seems to have been Rivera's recognition that Kahlo's health would inexorably deteriorate, and that she needed someone to look after her. |

|||

Kahlo was deeply influenced by indigenous Mexican culture, which is apparent in her use of bright colors and dramatic symbolism. She frequently included the symbolic [[monkey]]. In Mexican [[mythology]], monkeys are symbols of lust, but Kahlo portrayed them as tender and protective symbols. [[Christian]] and [[Jewish]] themes are often depicted in her work. |

|||

"Her health, never at any time robust, grew visibly worse from about 1944 onwards, and Kahlo underwent the first many operations on her spine and her crippled foot. Authorities on her life and work have questioned whether all these operations were really necessary, or whether they were in fact a way of holding Rivera's attention in the face of his numerous affairs with other women. In Kahlo's case, her physical and psychological sufferings were always linked. in early 1950, her physical state reached a crisis, and she had to go into hospital in Mexico City, where she remained for a year. |

|||

She also combined elements of the classic religious Mexican tradition with [[surrealist]] renderings. Kahlo created a few drawings of "portraits," but unlike her paintings, they were more abstract. She did one of her husband, Diego Rivera,<ref>[http://artsalesindex.artinfo.com/artsalesindex/asi/lots/10772867 Kahlo's ''Surrealist drawing, Diego']</ref> and of herself.<ref>[http://artsalesindex.artinfo.com/artsalesindex/asi/lots/10772866 Kahlo's ''Surrealist drawing, Frida'']</ref> |

|||

"During the period after her remarriage, her artistic reputation continued to grow, though at first more rapidly in the United States than in Mexico itself. she was included in prestigious group shows in the Museum of Modern Art, the Boston Institute of Contemporary Arts and the Philadelphia Museum of Art. In 1946, however, she received a Mexican government fellowship, and in the same year an official prize on the occasion of the Annual National Exhibition. She also took up teaching at the new experimental art school 'La Esmeralda', and, despite her unconventional methods, proved an inspiration to her students. After her return home from hospital, Kahlo became an increasingly fervent and impassioned Communist. Rivera had been expelled from the Party, which was reluctant to receive him back, both because of his links with the Mexican government of the day, and because of his association with Trotsky. Kahlo boasted: 'I was a member of the Party before I met Diego and I think I am a better Communist than he is or ever will be.' |

|||

At the invitation of [[André Breton]], she went to [[France]] in 1939 and was featured at an exhibition of her paintings in [[Paris, France|Paris]]. The [[Louvre]] bought one of her paintings, ''The Frame'', which was displayed at the exhibit. This was the first work by a 20th century Mexican artist ever purchased by the internationally renowned museum. |

|||

==Marriage== |

|||

"While the 1940s had seen her produce some of her finest work, her paintings now became more clumsy and chaotic, thanks to the joint effects of pain, drugs and drink. Despite this, in 1954 she was offered her first solo show in Mexico itself - which was to be the only such show held in her own lifetime. It took place at the fashionable Galeria de Arte Contemporaneo in the Zona Rosa of Mexico City. At first it seemed that Kahlo would be too ill to attend, but she sent her richly decorated fourposter bed ahead of her, arrived by ambulance, and was carried into the gallery on a stretcher. The private view was a triumphal occasion. |

|||

[[Image:Block Kahlo Rivera 1932.jpg|thumb|left|250px|Frida Kahlo (center) and [[Diego Rivera]] photographed by [[Carl Van Vechten]] in 1932]] |

|||

"In the same year, Kahlo, threatened by gangrene, had her right leg amputated below the knee. It was a tremendous blow to someone who had invested so much in the elaboration of her own self image. She learned to walk again with an artificial limb, and even (briefly and with the help of pain-killing drugs) danced at celebrations with friends. But the end was close. In July 1954, she made her last public appearance, when she participated in a Communist demonstration against the overthrow of the left-wing Guatemalan president Jacobo Arbenz. Soon afterwards, she died in her sleep, apparently as the result of an embolism, though there was a suspicion among those close to her that she had found a way to commit suicide. Her last diary entry read: 'I hope the end is joyful - and I hope never to come back - Frida.'" |

|||

As a young artist, Kahlo approached the famous Mexican painter, [[Diego Rivera]], whose work she admired, asking him for advice about pursuing art as a career. He immediately recognized her talent and her unique expression as truly special and uniquely Mexican. He encouraged her development as an artist and soon began an intimate relationship with Frida. They were married in 1929, despite the disapproval of Frida's mother. They often were referred to as ''The [[Elephant]] and the [[Dove]]'', a nickname that originated when Kahlo's father used it to express their extreme difference in size.{{Fact|date=June 2008}} |

|||

- Text from Edward Lucie-Smith, "Lives of the Great 20th-Century Artists" |

|||

Their marriage often was tumultuous. Notoriously, both Kahlo and Rivera had fiery temperaments and both had numerous extramarital affairs. The openly [[bisexual]] Kahlo had affairs with both men (including [[Leon Trotsky]]) and women;<ref name=herrera /> Rivera knew of and tolerated her relationships with women, but her relationships with men made him jealous. For her part, Kahlo was furious when she learned that Rivera had an affair with her younger sister, Cristina. The couple eventually [[divorce]]d, but remarried in 1940. Their second marriage was as turbulent as the first. Their living quarters often were separate, although sometimes adjacent. |

|||

Books and videos on Frida Kahlo: |

|||

==Later years and death== |

|||

[[Image:The Blue House 7.jpg|thumb|right|''La Casa Azul'', photo taken in 2005.]] |

|||

Active [[communist]] sympathizers, Kahlo and Rivera befriended [[Leon Trotsky]] as he sought political sanctuary from [[Joseph Stalin]]'s regime in the [[Soviet Union]]. Initially, Trotsky lived with Rivera and then at Kahlo's home, where they reportedly had an affair.<ref name=herrera /> Trotsky and his wife then moved to another house in [[Coyoacán]] where, later, he was assassinated. |

|||

A few days before Frida Kahlo died on July 13, 1954, she wrote in her diary: "I hope the exit is joyful - and I hope never to return - Frida".<ref name=herrera /> The official cause of death was given as a [[pulmonary embolism]], although some suspected that she died from an [[overdose]] that may or may not have been accidental.<ref name=herrera /> An [[autopsy]] was never performed. She had been very ill throughout the previous year and her right leg had been amputated at the knee, owing to [[gangrene]]. She also had a bout of [[bronchopneumonia]] near that time, which had left her quite frail.<ref name=herrera /> |

|||

Later, in his autobiography, Diego Rivera wrote that the day Kahlo died was the most tragic day of his life, adding that, too late, he had realized that the most wonderful part of his life had been his love for her.<ref name=herrera /> |

|||

A [[pre-Columbian]] urn holding her ashes is on display in her former home, ''La Casa Azul'' (The Blue House), in Coyoacán. Today it is a museum housing a number of her works of art and numerous relics from her personal life.<ref name=herrera /> |

|||

==Later recognition== |

|||

Kahlo's work was not widely recognized until decades after her death. Often she was popularly remembered only as [[Diego Rivera]]'s wife. It was not until the early 1980s, when the artistic movement in [[Mexico]] known as ''Neomexicanismo'' began, that she became very prominent.<ref name=Emerich>{{cite book | last = Emerich| first = Luis Carlos | authorlink = Luis Carlos Emerich | title = Figuraciones y desfiguros de los ochentas | publisher = Editorial Diana| year= 1989 | location = Mexico City | id = ISBN-968-13-1908-7}}</ref> This movement recognized the values of contemporary Mexican culture; it was the moment when artists such as Kahlo, Abraham Angel, Angel Zárraga, and others became household names and Helguera's classical calendar paintings achieved fame.<ref name=Emerich/> |

Kahlo's work was not widely recognized until decades after her death. Often she was popularly remembered only as [[Diego Rivera]]'s wife. It was not until the early 1980s, when the artistic movement in [[Mexico]] known as ''Neomexicanismo'' began, that she became very prominent.<ref name=Emerich>{{cite book | last = Emerich| first = Luis Carlos | authorlink = Luis Carlos Emerich | title = Figuraciones y desfiguros de los ochentas | publisher = Editorial Diana| year= 1989 | location = Mexico City | id = ISBN-968-13-1908-7}}</ref> This movement recognized the values of contemporary Mexican culture; it was the moment when artists such as Kahlo, Abraham Angel, Angel Zárraga, and others became household names and Helguera's classical calendar paintings achieved fame.<ref name=Emerich/> |

||

During the same decade several other factors helped to establish her success. The movie ''Frida, naturaleza viva'' (1983), directed by [[Paul Leduc]] with [[Ofelia Medina]] as Frida and painter [[Juan José Gurrola]] as Diego, was a huge success. For the rest of her life, Medina has remained in a sort of perpetual Frida role.<ref name="Cada quien su frida">{{cite web | title=Cada quién su Frida, stage piece | work=Cada quien su Frida | url=http://www.cadaquiensufrida.blogspot.com/ | accessdate=2007-08-19}}</ref> Also during the same time [[Hayden Herrera]] published a determinant and influential biography: ''Frida: The Biography of Frida Kahlo'', which became a worldwide bestseller. |

During the same decade several other factors helped to establish her success. The movie ''Frida, naturaleza viva'' (1983), directed by [[Paul Leduc]] with [[Ofelia Medina]] as Frida and painter [[Juan José Gurrola]] as Diego, was a huge success. For the rest of her life, Medina has remained in a sort of perpetual Frida role.<ref name="Cada quien su frida">{{cite web | title=Cada quién su Frida, stage piece | work=Cada quien su Frida | url=http://www.cadaquiensufrida.blogspot.com/ | accessdate=2007-08-19}}</ref> Also during the same time [[Hayden Herrera]] published a determinant and influential biography: ''Frida: The Biography of Frida Kahlo'', which became a worldwide bestseller. |

||

Revision as of 01:16, 11 February 2009

Frida Kahlo | |

|---|---|

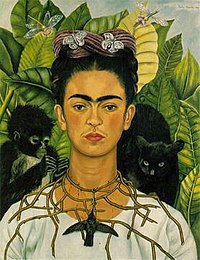

Frida Kahlo, Self-portrait with Thorn Necklace and Hummingbird, Nikolas Muray Collection, Harry Ransom Center, The University of Texas at Austin[1] | |

| Born | Magdalena Carmen Frida Kahlo y Calderón |

| Nationality | Mexican |

| Education | Self–taught |

| Known for | Painting |

| Notable work | in museums:

|

| Movement | Surrealism |

| Patron(s) | and friends:

|

Frida Kahlo (July 6, 1907 – July 13, 1954) was a Mexican painter, who has achieved great international popularity.[2] She painted using vibrant colours in a style that was influenced by indigenous cultures of Mexico as well as by European influences that include Realism, Symbolism, and Surrealism. Many of her works are self-portraits that symbolically express her own pain and sexuality.

In 1929 Kahlo married the Mexican muralist Diego Rivera. Her "Blue" house in Coyoacán, Mexico City is a museum, donated by Diego Rivera upon his death in 1957.

Childhood and family

Magdalena Carmen Frida Kahlo y Calderón (as her name appears on her birth certificate[3]) was born on July 6, 1907 in the house of her parents, known as La Casa Azul (The Blue House), in Coyoacán. At the time, this was a small town on the outskirts of Mexico City.

Her father, Guillermo Kahlo (1872-1941), was born Carl Wilhelm Kahlo in Pforzheim, Germany. He was the son of the painter and goldsmith Jakob Heinrich Kahlo and Henriett E. Kaufmann. Kahlo claimed her father was of Jewish and Hungarian ancestry,[4] but a 2005 book on Guillermo Kahlo, Fridas Vater (Schirmer/Mosel, 2005), states that he was descended from a long line of German Lutherans.[5] Wilhelm Kahlo sailed to Mexico in 1891 at the age of nineteen and, upon his arrival, changed his German forename, Wilhelm, to its Spanish equivalent, 'Guillermo'. During the late 1930s, in the face of rising Nazism in Germany, Frida acknowledged and asserted her German heritage by spelling her name, Frieda (an allusion to "Frieden", which means "peace" in German).

Frida's mother, Matilde Calderón y Gonzalez, was a devout Catholic of primarily indigenous, as well as Spanish descent.[4] Frida's parents were married shortly after the death of Guillermo's first wife during the birth of her second child. Although their marriage was quite unhappy, Guillermo and Matilde had four daughters, with Frida being the third. She had two older half sisters. Frida once remarked that she grew up in a world surrounded by females. Throughout most of her life, however, Frida remained close to her father.

The Mexican Revolution began in 1910 when Kahlo was three years old. Later, however, Kahlo claimed that she was born in 1910 so people would directly associate her with the revolution. In her writings, she recalled that her mother would usher her and her sisters inside the house as gunfire echoed in the streets of her hometown, which was extremely poor at the time. Occasionally, men would leap over the walls into their backyard and sometimes her mother would prepare a meal for the hungry revolutionaries.

Kahlo contracted polio at age six, which left her right leg thinner than the left, which Kahlo disguised by wearing long skirts. It has been conjectured that she also suffered from spina bifida, a congenital disease that could have affected both spinal and leg development.[6] As a girl, she participated in boxing and other sports. In 1922, Kahlo was enrolled in the Preparatoria, one of Mexico's premier schools, where she was one of only thirty-five girls. Kahlo joined a clique at the school and fell in love with the leader, Alejandro Gomez Arias. During this period, Kahlo also witnessed violent armed struggles in the streets of Mexico City as the Mexican Revolution continued.

On September 17, 1925, Kahlo was riding in a bus when the vehicle collided with a trolley car. She suffered serious injuries in the accident, including a broken spinal column, a broken collarbone, broken ribs, a broken pelvis, eleven fractures in her right leg, a crushed and dislocated right foot, and a dislocated shoulder. An iron handrail pierced her abdomen and her uterus, which seriously damaged her reproductive ability.

Although she recovered from her injuries and eventually regained her ability to walk, she was plagued by relapses of extreme pain for the remainder of her life. The pain was intense and often left her confined to a hospital or bedridden for months at a time. She underwent as many as thirty-five operations as a result of the accident, mainly on her back, her right leg and her right foot.

Career as painter

After the accident, Kahlo turned her attention away from the study of medicine to begin a full-time painting career. The accident left her in a great deal of pain while she recovered in a full body cast; she painted to occupy her time during her temporary state of immobilization. Her self-portraits became a dominant part of her life when she was immobile for three months after her accident. Kahlo once said, "I paint myself because I am often alone and I am the subject I know best." Her mother had a special easel made for her so she could paint in bed, and her father lent her his box of oil paints and some brushes.[7]

Drawing on personal experiences, including her marriage, her miscarriages, and her numerous operations, Kahlo's works often are characterized by their stark portrayals of pain. Of her 143 paintings, 55 are self-portraits which often incorporate symbolic portrayals of physical and psychological wounds. She insisted, "I never painted dreams. I painted my own reality."

Kahlo was deeply influenced by indigenous Mexican culture, which is apparent in her use of bright colors and dramatic symbolism. She frequently included the symbolic monkey. In Mexican mythology, monkeys are symbols of lust, but Kahlo portrayed them as tender and protective symbols. Christian and Jewish themes are often depicted in her work.

She also combined elements of the classic religious Mexican tradition with surrealist renderings. Kahlo created a few drawings of "portraits," but unlike her paintings, they were more abstract. She did one of her husband, Diego Rivera,[8] and of herself.[9] At the invitation of André Breton, she went to France in 1939 and was featured at an exhibition of her paintings in Paris. The Louvre bought one of her paintings, The Frame, which was displayed at the exhibit. This was the first work by a 20th century Mexican artist ever purchased by the internationally renowned museum.

Marriage

As a young artist, Kahlo approached the famous Mexican painter, Diego Rivera, whose work she admired, asking him for advice about pursuing art as a career. He immediately recognized her talent and her unique expression as truly special and uniquely Mexican. He encouraged her development as an artist and soon began an intimate relationship with Frida. They were married in 1929, despite the disapproval of Frida's mother. They often were referred to as The Elephant and the Dove, a nickname that originated when Kahlo's father used it to express their extreme difference in size.[citation needed]

Their marriage often was tumultuous. Notoriously, both Kahlo and Rivera had fiery temperaments and both had numerous extramarital affairs. The openly bisexual Kahlo had affairs with both men (including Leon Trotsky) and women;[3] Rivera knew of and tolerated her relationships with women, but her relationships with men made him jealous. For her part, Kahlo was furious when she learned that Rivera had an affair with her younger sister, Cristina. The couple eventually divorced, but remarried in 1940. Their second marriage was as turbulent as the first. Their living quarters often were separate, although sometimes adjacent.

Later years and death

Active communist sympathizers, Kahlo and Rivera befriended Leon Trotsky as he sought political sanctuary from Joseph Stalin's regime in the Soviet Union. Initially, Trotsky lived with Rivera and then at Kahlo's home, where they reportedly had an affair.[3] Trotsky and his wife then moved to another house in Coyoacán where, later, he was assassinated.

A few days before Frida Kahlo died on July 13, 1954, she wrote in her diary: "I hope the exit is joyful - and I hope never to return - Frida".[3] The official cause of death was given as a pulmonary embolism, although some suspected that she died from an overdose that may or may not have been accidental.[3] An autopsy was never performed. She had been very ill throughout the previous year and her right leg had been amputated at the knee, owing to gangrene. She also had a bout of bronchopneumonia near that time, which had left her quite frail.[3]

Later, in his autobiography, Diego Rivera wrote that the day Kahlo died was the most tragic day of his life, adding that, too late, he had realized that the most wonderful part of his life had been his love for her.[3]

A pre-Columbian urn holding her ashes is on display in her former home, La Casa Azul (The Blue House), in Coyoacán. Today it is a museum housing a number of her works of art and numerous relics from her personal life.[3]

Later recognition

Kahlo's work was not widely recognized until decades after her death. Often she was popularly remembered only as Diego Rivera's wife. It was not until the early 1980s, when the artistic movement in Mexico known as Neomexicanismo began, that she became very prominent.[10] This movement recognized the values of contemporary Mexican culture; it was the moment when artists such as Kahlo, Abraham Angel, Angel Zárraga, and others became household names and Helguera's classical calendar paintings achieved fame.[10] During the same decade several other factors helped to establish her success. The movie Frida, naturaleza viva (1983), directed by Paul Leduc with Ofelia Medina as Frida and painter Juan José Gurrola as Diego, was a huge success. For the rest of her life, Medina has remained in a sort of perpetual Frida role.[11] Also during the same time Hayden Herrera published a determinant and influential biography: Frida: The Biography of Frida Kahlo, which became a worldwide bestseller.

Raquel Tibol, a Mexican artist and personal friend of Frida, wrote Frida Kahlo: una vida abierta. Other works about her include a biography by Mexican art critic and psychoanalist Teresa del Conde and texts by other Mexican critics and theorists such as Jorge Alberto Manrique.[10]

On June 21, 2001, she became the first Hispanic woman to be honored with a U.S. postage stamp.[12]

In 2002 the American biographical film, Frida, directed by Julie Taymor, in which Salma Hayek portrayed the artist, was released.[13] It grossed US$58 million worldwide.[13]

In 2006, Kahlo's 1943 painting Roots set a US$5.6 million auction record for a Latin American work.[14]

Influence on other artists

Frida Kahlo was photographed by many artists including Carl Van Vechten, Edward Weston, Héctor García, Imogen Cunningham, Manuel Alvarez Bravo, Lola Alvarez Bravo, Nicholas Murray, Guillermo Zamora, Tina Modotti, and Lucienne Bloch.[15] Many Chicana/o artists have included versions of her self portraits in their work, among them Rupert García, Alfredo Arreguín, Yreina D. Cervántez, Marcos Raya, Gilbert Hernández, and Carmen Lomas Garza.

Centennial celebrations

The 100th anniversary of the birth of Frida Kahlo honored her with the largest exhibit ever held of her paintings at the Museum of the Fine Arts Palace, Kahlo's first comprehensive exhibit in Mexico.[16] Works were on loan from Detroit, Minneapolis, Miami, Los Angeles, San Francisco, and Nagoya, Japan. The exhibit included one-third of her artistic production, as well as manuscripts and letters that had not been displayed previously.[16] The exhibit was open June 13 through August 12, 2007 and broke all attendance records at the museum.[17] Some of her work was on exhibit in Monterrey, Nuevo León, and moved in September 2007 to museums in the United States.

In 2008, the first major Frida Kahlo exhibition in the United States in nearly fifteen years included stops at the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis, the Philadelphia Museum of Art and the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art with over forty of her self-portraits, still lives, and portraits from the beginning of her career in 1926 until her death in 1954.

Previously, the most recent international exhibition of Kahlo's work had been in 2005 in London, which brought together eighty-seven of her works.

La Casa Azul

Kahlo's Casa Azul (Blue House), where she lived and worked in Mexico City, is now a museum housing artifacts of her life. Photographs may be taken only outside the house and in the courtyard area.

See also

References

- ^ Image—full description and credit: Frida Kahlo, Self-Portrait with Thorn Necklace and Hummingbird, 1940, oil on canvas on Masonite, 24-1/2 x 19 inches, Nikolas Muray Collection, Harry Ransom Center, The University of Texas at Austin, © 2007 Banco de México Diego Rivera & Frida Kahlo Museums Trust, Av. Cinco de Mayo No. 2, Col. Centro, Del. Cuauhtémoc 06059, México, D.F.

- ^ "Frida Kahlo". Smithsonian.com. Retrieved 2008-02-18.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Herrera, Hayden (1983). A Biography of Frida Kahlo. New York: HarperCollins. ISBN-13: 978-0060085896.

- ^ a b "Frida Kahlo (1907-1954), Mexican Painter". Biography, www.fridakahlo.com. Retrieved 2007-06-02.

- ^ Frida Kahlo's father wasn't Jewish after all, Meir Ronnen, April 20, 2006, "Books", Jerusalem Post

- ^ Budrys, Valmantas (2006). "Neurological Deficits in the Life and Work of Frida Kahlo". European Neurology. 55 (1). ISSN (print), ISSN = 1421-9913 (Online) 0014-3022 (print), ISSN = 1421-9913 (Online). Retrieved 2008-01-22.

{{cite journal}}: Check|issn=value (help); Missing pipe in:|issn=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Cruz, Barbara (1996). Frida Kahlo: Portrait of a Mexican Painter. Berkeley Heights: Enslow. p. 9. ISBN-13: 0-89490-765-4.

- ^ Kahlo's Surrealist drawing, Diego'

- ^ Kahlo's Surrealist drawing, Frida

- ^ a b c Emerich, Luis Carlos (1989). Figuraciones y desfiguros de los ochentas. Mexico City: Editorial Diana. ISBN-968-13-1908-7.

- ^ "Cada quién su Frida, stage piece". Cada quien su Frida. Retrieved 2007-08-19.

- ^ USPS - Stamp Release No. 01-048 - Postal Service Continues Its Celebration of Fine Arts With Frida Kahlo Stamp

- ^ a b Frida (2002)

- ^ "Frida Kahlo " Roots " Sets $5.6 Million Record at Sotheby's". Art Knowledge News. Retrieved 2007-09-23.

- ^ Lucienne Bloch website at Old Stage Studios

- ^ a b "Largest-ever exhibit of Frida Kahlo work to open in Mexico". Agence France Presse, Yahoo News (May 29, 2007). Retrieved 2007-05-30.

- ^ "Centenary show for Mexican painter Kahlo breaks attendance records". People's Daily Online (August 14, 2007). Retrieved 2007-08-21.

Bibliography

- Fuentes, C. (1998). Diary of Frida Kahlo. Harry N. Abrams, Inc. (March 1, 1998). ISBN 0-8109-8195-5.

- Gonzalez, M. (2005). Kahlo – A Life. Socialist Review, June 2005.

- Arts Galleries: Frida Khalo. Exhibition at Tate Modern, June 9 – October 9, 2005. The Guardian, Wednesday May 18, 2005. Retrieved May 18, 2005.

- Nericcio, William Anthony. (2005). A Decidedly 'Mexican' and 'American' Semi[erotic Transference: Frida Kahlo in the Eyes of Gilbert Hernandez].

- Turner, C. (2005). Photographing Frida Kahlo. The Guardian, Wednesday May 18, 2005. Retrieved May 18, 2005.

- Zamora, M. (1995). The Letters of Frida Kahlo: Cartas Apasionadas. Chronicle Books (November 1, 1995). ISBN 0-8118-1124-7

- The Diary of Frida Kahlo. Introduction by Carlos Fuentes. Essay by Sarah M. Lowe. London: Bloomsburry, 1995. ISBN 0-7475-2247-2

External links

This article's use of external links may not follow Wikipedia's policies or guidelines. |

- General internet resources

- "Frida Kahlo" at ArtCyclopedia

- Frida Kahlo at Olga's Gallery

- Kahlo paintings at Ten Dreams Galleries

- Frida Kahlo fan site with biography, paintings, and photos

- John Weatherwax Papers Relating to Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera at the Smithsonian's Archives of American Art

- www.frida-kahlo-foundation.org Paintings by Frida Kahlo

- Articles and essays

- "Frida Kahlo & contemporary thought"

- "Frida by Kahlo"

- Essay by William Nericcio on Kahlo and Chicano Graphic artist Gilbert Hernandez

- Exhibitions and museums

- "The Frida Kahlo Museum", by Gale Randall

- Exhibition guide from Tate Modern

- Frida Kahlo: Notas Sobre una Vida (Notes on a Life) online exhibition from the Smithsonian's Archives of American Art

- The Heart of Frida exhibition in San Miguel de Allende, Mexico showcasing recently discovered letters and artwork.

- Media portrayals