Quantum computing: Difference between revisions

m Reverted 1 edit by 171.159.192.10 (talk) to last revision by XLinkBot. (TW) |

|||

| Line 276: | Line 276: | ||

In May 2013, Google Inc announced that it was launching the Quantum Artificial Intelligence Lab, to be hosted by NASA’s Ames Research Center. The lab will house a 512-qubit quantum computer from D-Wave Systems, and the USRA (Universities Space Research Association) will invite researchers from around the world to share time on it. The goal being to study how quantum computing might advance machine learning<ref>{{cite web|title=Launching the Quantum Artificial Intelligence Lab|url=http://googleresearch.blogspot.co.uk/2013/05/launching-quantum-artificial.html|publisher=Research@Google Blog|accessdate=16 May 2013}}</ref> |

In May 2013, Google Inc announced that it was launching the Quantum Artificial Intelligence Lab, to be hosted by NASA’s Ames Research Center. The lab will house a 512-qubit quantum computer from D-Wave Systems, and the USRA (Universities Space Research Association) will invite researchers from around the world to share time on it. The goal being to study how quantum computing might advance machine learning<ref>{{cite web|title=Launching the Quantum Artificial Intelligence Lab|url=http://googleresearch.blogspot.co.uk/2013/05/launching-quantum-artificial.html|publisher=Research@Google Blog|accessdate=16 May 2013}}</ref> |

||

New Quantum Organic System on a the organic quantum computor level see the video new type of quantum computor on the rise is organic quantum system here take a look |

|||

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NyW1y39FTd4&feature=youtube_gdata_player |

|||

This veriation uses the solid state proccessing. |

|||

==Relation to computational complexity theory== |

==Relation to computational complexity theory== |

||

Revision as of 00:05, 9 July 2013

A quantum computer is a computation device that makes direct use of quantum-mechanical phenomena, such as superposition and entanglement, to perform operations on data. Quantum computers are different from digital computers based on transistors. Whereas digital computers require data to be encoded into binary digits (bits), quantum computation uses quantum properties to represent data and perform operations on these data.[1] A theoretical model is the quantum Turing machine, also known as the universal quantum computer. Quantum computers share theoretical similarities with non-deterministic and probabilistic computers. One example is the ability to be in more than one state simultaneously. The field of quantum computing was first introduced by Yuri Manin in 1980[2] and Richard Feynman in 1981.[3][4] A quantum computer with spins as quantum bits was also formulated for use as a quantum space-time in 1969.[5]

Although quantum computing is still in its infancy, experiments have been carried out in which quantum computational operations were executed on a very small number of qubits (quantum bits).[6] Both practical and theoretical research continues, and many national governments and military funding agencies support quantum computing research to develop quantum computers for both civilian and national security purposes, such as cryptanalysis.[7]

Large-scale quantum computers will be able to solve certain problems much faster than any classical computer using the best currently known algorithms, like integer factorization using Shor's algorithm or the simulation of quantum many-body systems. There exist quantum algorithms, such as Simon's algorithm, which run faster than any possible probabilistic classical algorithm.[8] Given sufficient computational resources, a classical computer could be made to simulate any quantum algorithm; quantum computation does not violate the Church–Turing thesis.[9] However, the computational basis of 500 qubits, for example, would already be too large to be represented on a classical computer because it would require 2500 complex values (2501 bits) to be stored.[10] (For comparison, a terabyte of digital information is only 243 bits.)

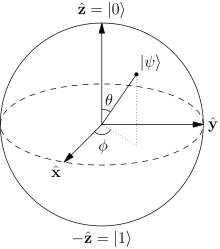

Basis

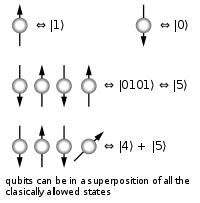

A classical computer has a memory made up of bits, where each bit represents either a one or a zero. A quantum computer maintains a sequence of qubits. A single qubit can represent a one, a zero, or any quantum superposition of these two qubit states; moreover, a pair of qubits can be in any quantum superposition of 4 states, and three qubits in any superposition of 8. In general, a quantum computer with qubits can be in an arbitrary superposition of up to different states simultaneously (this compares to a normal computer that can only be in one of these states at any one time). A quantum computer operates by setting the qubits in a controlled initial state that represents the problem at hand and by manipulating those qubits with a fixed sequence of quantum logic gates. The sequence of gates to be applied is called a quantum algorithm. The calculation ends with measurement of all the states, collapsing each qubit into one of the two pure states, so the outcome can be at most classical bits of information.

An example of an implementation of qubits for a quantum computer could start with the use of particles with two spin states: "down" and "up" (typically written and , or and ). But in fact any system possessing an observable quantity A, which is conserved under time evolution such that A has at least two discrete and sufficiently spaced consecutive eigenvalues, is a suitable candidate for implementing a qubit. This is true because any such system can be mapped onto an effective spin-1/2 system.

Bits vs. qubits

A quantum computer with a given number of qubits is fundamentally different from a classical computer composed of the same number of classical bits. For example, to represent the state of an n-qubit system on a classical computer would require the storage of 2n complex coefficients. Although this fact may seem to indicate that qubits can hold exponentially more information than their classical counterparts, care must be taken not to overlook the fact that the qubits are only in a probabilistic superposition of all of their states. This means that when the final state of the qubits is measured, they will only be found in one of the possible configurations they were in before measurement. Moreover, it is incorrect to think of the qubits as only being in one particular state before measurement since the fact that they were in a superposition of states before the measurement was made directly affects the possible outcomes of the computation.

For example: Consider first a classical computer that operates on a three-bit register. The state of the computer at any time is a probability distribution over the different three-bit strings 000, 001, 010, 011, 100, 101, 110, 111. If it is a deterministic computer, then it is in exactly one of these states with probability 1. However, if it is a probabilistic computer, then there is a possibility of it being in any one of a number of different states. We can describe this probabilistic state by eight nonnegative numbers A,B,C,D,E,F,G,H (where A = probability computer is in state 000, B = probability computer is in state 001, etc.). There is a restriction that these probabilities sum to 1.

The state of a three-qubit quantum computer is similarly described by an eight-dimensional vector (a,b,c,d,e,f,g,h), called a ket. However, instead of adding to one, the sum of the squares of the coefficient magnitudes, , must equal one. Moreover, the coefficients can have complex values. Since the absolute square of these complex-valued coefficients denote probability amplitudes of given states, the phase between any two coefficients (states) represents a meaningful parameter, which presents a fundamental difference between quantum computing and probabilistic classical computing.[12]

If you measure the three qubits, you will observe a three-bit string. The probability of measuring a given string is the squared magnitude of that string's coefficient (i.e., the probability of measuring 000 = , the probability of measuring 001 = , etc..). Thus, measuring a quantum state described by complex coefficients (a,b,...,h) gives the classical probability distribution and we say that the quantum state "collapses" to a classical state as a result of making the measurement.

Note that an eight-dimensional vector can be specified in many different ways depending on what basis is chosen for the space. The basis of bit strings (e.g., 000, 001, ..., 111) is known as the computational basis. Other possible bases are unit-length, orthogonal vectors and the eigenvectors of the Pauli-x operator. Ket notation is often used to make the choice of basis explicit. For example, the state (a,b,c,d,e,f,g,h) in the computational basis can be written as:

- where, e.g.,

The computational basis for a single qubit (two dimensions) is and .

Using the eigenvectors of the Pauli-x operator, a single qubit is and .

Operation

While a classical three-bit state and a quantum three-qubit state are both eight-dimensional vectors, they are manipulated quite differently for classical or quantum computation. For computing in either case, the system must be initialized, for example into the all-zeros string, , corresponding to the vector (1,0,0,0,0,0,0,0). In classical randomized computation, the system evolves according to the application of stochastic matrices, which preserve that the probabilities add up to one (i.e., preserve the L1 norm). In quantum computation, on the other hand, allowed operations are unitary matrices, which are effectively rotations (they preserve that the sum of the squares add up to one, the Euclidean or L2 norm). (Exactly what unitaries can be applied depend on the physics of the quantum device.) Consequently, since rotations can be undone by rotating backward, quantum computations are reversible. (Technically, quantum operations can be probabilistic combinations of unitaries, so quantum computation really does generalize classical computation. See quantum circuit for a more precise formulation.)

Finally, upon termination of the algorithm, the result needs to be read off. In the case of a classical computer, we sample from the probability distribution on the three-bit register to obtain one definite three-bit string, say 000. Quantum mechanically, we measure the three-qubit state, which is equivalent to collapsing the quantum state down to a classical distribution (with the coefficients in the classical state being the squared magnitudes of the coefficients for the quantum state, as described above), followed by sampling from that distribution. Note that this destroys the original quantum state. Many algorithms will only give the correct answer with a certain probability. However, by repeatedly initializing, running and measuring the quantum computer, the probability of getting the correct answer can be increased.

For more details on the sequences of operations used for various quantum algorithms, see universal quantum computer, Shor's algorithm, Grover's algorithm, Deutsch-Jozsa algorithm, amplitude amplification, quantum Fourier transform, quantum gate, quantum adiabatic algorithm and quantum error correction.

Potential

Integer factorization is believed to be computationally infeasible with an ordinary computer for large integers if they are the product of few prime numbers (e.g., products of two 300-digit primes).[13] By comparison, a quantum computer could efficiently solve this problem using Shor's algorithm to find its factors. This ability would allow a quantum computer to decrypt many of the cryptographic systems in use today, in the sense that there would be a polynomial time (in the number of digits of the integer) algorithm for solving the problem. In particular, most of the popular public key ciphers are based on the difficulty of factoring integers (or the related discrete logarithm problem, which can also be solved by Shor's algorithm), including forms of RSA. These are used to protect secure Web pages, encrypted email, and many other types of data. Breaking these would have significant ramifications for electronic privacy and security.

However, other existing cryptographic algorithms do not appear to be broken by these algorithms.[14][15] Some public-key algorithms are based on problems other than the integer factorization and discrete logarithm problems to which Shor's algorithm applies, like the McEliece cryptosystem based on a problem in coding theory.[14][16] Lattice-based cryptosystems are also not known to be broken by quantum computers, and finding a polynomial time algorithm for solving the dihedral hidden subgroup problem, which would break many lattice based cryptosystems, is a well-studied open problem.[17] It has been proven that applying Grover's algorithm to break a symmetric (secret key) algorithm by brute force requires time equal to roughly 2n/2 invocations of the underlying cryptographic algorithm, compared with roughly 2n in the classical case,[18] meaning that symmetric key lengths are effectively halved: AES-256 would have the same security against an attack using Grover's algorithm that AES-128 has against classical brute-force search (see Key size). Quantum cryptography could potentially fulfill some of the functions of public key cryptography.

Besides factorization and discrete logarithms, quantum algorithms offering a more than polynomial speedup over the best known classical algorithm have been found for several problems,[19] including the simulation of quantum physical processes from chemistry and solid state physics, the approximation of Jones polynomials, and solving Pell's equation. No mathematical proof has been found that shows that an equally fast classical algorithm cannot be discovered, although this is considered unlikely. For some problems, quantum computers offer a polynomial speedup. The most well-known example of this is quantum database search, which can be solved by Grover's algorithm using quadratically fewer queries to the database than are required by classical algorithms. In this case the advantage is provable. Several other examples of provable quantum speedups for query problems have subsequently been discovered, such as for finding collisions in two-to-one functions and evaluating NAND trees.

Consider a problem that has these four properties:

- The only way to solve it is to guess answers repeatedly and check them,

- The number of possible answers to check is the same as the number of inputs,

- Every possible answer takes the same amount of time to check, and

- There are no clues about which answers might be better: generating possibilities randomly is just as good as checking them in some special order.

An example of this is a password cracker that attempts to guess the password for an encrypted file (assuming that the password has a maximum possible length).

For problems with all four properties, the time for a quantum computer to solve this will be proportional to the square root of the number of inputs. That can be a very large speedup, reducing some problems from years to seconds. It can be used to attack symmetric ciphers such as Triple DES and AES by attempting to guess the secret key.

Grover's algorithm can also be used to obtain a quadratic speed-up over a brute-force search for a class of problems known as NP-complete.

Since chemistry and nanotechnology rely on understanding quantum systems, and such systems are impossible to simulate in an efficient manner classically, many believe quantum simulation will be one of the most important applications of quantum computing.[20]

There are a number of technical challenges in building a large-scale quantum computer, and thus far quantum computers have yet to solve a problem faster than a classical computer. David DiVincenzo, of IBM, listed the following requirements for a practical quantum computer:[21]

- scalable physically to increase the number of qubits;

- qubits can be initialized to arbitrary values;

- quantum gates faster than decoherence time;

- universal gate set;

- qubits can be read easily.

Quantum decoherence

One of the greatest challenges is controlling or removing quantum decoherence. This usually means isolating the system from its environment as interactions with the external world cause the system to decohere. This effect is irreversible, as it is non-unitary, and is usually something that should be highly controlled, if not avoided. Decoherence times for candidate systems, in particular the transverse relaxation time T2 (for NMR and MRI technology, also called the dephasing time), typically range between nanoseconds and seconds at low temperature.[12]

These issues are more difficult for optical approaches as the timescales are orders of magnitude shorter and an often-cited approach to overcoming them is optical pulse shaping. Error rates are typically proportional to the ratio of operating time to decoherence time, hence any operation must be completed much more quickly than the decoherence time.

If the error rate is small enough, it is thought to be possible to use quantum error correction, which corrects errors due to decoherence, thereby allowing the total calculation time to be longer than the decoherence time. An often cited figure for required error rate in each gate is 10−4. This implies that each gate must be able to perform its task in one 10,000th of the decoherence time of the system.

Meeting this scalability condition is possible for a wide range of systems. However, the use of error correction brings with it the cost of a greatly increased number of required qubits. The number required to factor integers using Shor's algorithm is still polynomial, and thought to be between L and L2, where L is the number of bits in the number to be factored; error correction algorithms would inflate this figure by an additional factor of L. For a 1000-bit number, this implies a need for about 104 qubits without error correction.[22] With error correction, the figure would rise to about 107 qubits. Note that computation time is about or about steps and on 1 MHz, about 10 seconds.

A very different approach to the stability-decoherence problem is to create a topological quantum computer with anyons, quasi-particles used as threads and relying on braid theory to form stable logic gates.[23][24]

Developments

There are a number of quantum computing models, distinguished by the basic elements in which the computation is decomposed. The four main models of practical importance are:

- Quantum gate array (computation decomposed into sequence of few-qubit quantum gates)

- One-way quantum computer (computation decomposed into sequence of one-qubit measurements applied to a highly entangled initial state or cluster state)

- Adiabatic quantum computer or computer based on Quantum annealing (computation decomposed into a slow continuous transformation of an initial Hamiltonian into a final Hamiltonian, whose ground states contains the solution)[25]

- Topological quantum computer[26] (computation decomposed into the braiding of anyons in a 2D lattice)

The Quantum Turing machine is theoretically important but direct implementation of this model is not pursued. All four models of computation have been shown to be equivalent to each other in the sense that each can simulate the other with no more than polynomial overhead.

For physically implementing a quantum computer, many different candidates are being pursued, among them (distinguished by the physical system used to realize the qubits):

- Superconductor-based quantum computers (including SQUID-based quantum computers)[27][28] (qubit implemented by the state of small superconducting circuits (Josephson junctions))

- Trapped ion quantum computer (qubit implemented by the internal state of trapped ions)

- Optical lattices (qubit implemented by internal states of neutral atoms trapped in an optical lattice)

- electrically defined or self-assembled quantum dots (e.g. the Loss-DiVincenzo quantum computer or[29]) (qubit given by the spin states of an electron trapped in the quantum dot)

- Quantum dot charge based semiconductor quantum computer (qubit is the position of an electron inside a double quantum dot)[30]

- Nuclear magnetic resonance on molecules in solution (liquid-state NMR) (qubit provided by nuclear spins within the dissolved molecule)

- Solid-state NMR Kane quantum computers (qubit realized by the nuclear spin state of phosphorus donors in silicon)

- Electrons-on-helium quantum computers (qubit is the electron spin)

- Cavity quantum electrodynamics (CQED) (qubit provided by the internal state of atoms trapped in and coupled to high-finesse cavities)

- Molecular magnet

- Fullerene-based ESR quantum computer (qubit based on the electronic spin of atoms or molecules encased in fullerene structures)

- Optics-based quantum computer (Quantum optics) (qubits realized by appropriate states of different modes of the electromagnetic field, e.g.[31])

- Diamond-based quantum computer[32][33][34] (qubit realized by the electronic or nuclear spin of Nitrogen-vacancy centers in diamond)

- Bose–Einstein condensate-based quantum computer[35]

- Transistor-based quantum computer – string quantum computers with entrainment of positive holes using an electrostatic trap

- Rare-earth-metal-ion-doped inorganic crystal based quantum computers[36][37] (qubit realized by the internal electronic state of dopants in optical fibers)

The large number of candidates demonstrates that the topic, in spite of rapid progress, is still in its infancy. But at the same time, there is also a vast amount of flexibility.

In 2001, researchers were able to demonstrate Shor's algorithm to factor the number 15 using a 7-qubit NMR computer.[38]

In 2005, researchers at the University of Michigan built a semiconductor chip that functioned as an ion trap. Such devices, produced by standard lithography techniques, may point the way to scalable quantum computing tools.[39] An improved version was made in 2006.[citation needed]

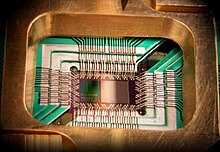

In 2009, researchers at Yale University created the first rudimentary solid-state quantum processor. The two-qubit superconducting chip was able to run elementary algorithms. Each of the two artificial atoms (or qubits) were made up of a billion aluminum atoms but they acted like a single one that could occupy two different energy states.[40][41]

Another team, working at the University of Bristol, also created a silicon-based quantum computing chip, based on quantum optics. The team was able to run Shor's algorithm on the chip.[42] Further developments were made in 2010.[43] Springer publishes a journal ("Quantum Information Processing") devoted to the subject.[44]

In April 2011, a team of scientists from Australia and Japan made a breakthrough in quantum teleportation. They successfully transferred a complex set of quantum data with full transmission integrity achieved. Also the qubits being destroyed in one place but instantaneously resurrected in another, without affecting their superpositions.[45][46]

In 2011, D-Wave Systems announced the first commercial quantum annealer on the market by the name D-Wave One. The company claims this system uses a 128 qubit processor chipset.[47] On May 25, 2011 D-Wave announced that Lockheed Martin Corporation entered into an agreement to purchase a D-Wave One system.[48] Lockheed Martin and the University of Southern California (USC) reached an agreement to house the D-Wave One Adiabatic Quantum Computer at the newly formed USC Lockheed Martin Quantum Computing Center, part of USC's Information Sciences Institute campus in Marina del Rey.[49] D-Wave's engineers use an empirical approach when designing their quantum chips, focusing on whether the chips are able to solve particular problems rather than designing based on a thorough understanding of the quantum principles involved. This approach was liked by investors more than by some academic critics, who said that D-Wave had not yet sufficiently demonstrated that they really had a quantum computer. Such criticism softened once D-Wave published a paper in Nature giving details, which critics said proved that the company's chips did have some of the quantum mechanical properties needed for quantum computing.[50][51]

During the same year, researchers working at the University of Bristol created an all-bulk optics system able to run an iterative version of Shor's algorithm. They successfully managed to factorize 21.[52]

In September 2011 researchers also proved that a quantum computer can be made with a Von Neumann architecture (separation of RAM).[53]

In November 2011 researchers factorized 143 using 4 qubits.[54]

In February 2012 IBM scientists said that they had made several breakthroughs in quantum computing that put them "on the cusp of building systems that will take computing to a whole new level."[55]

In April 2012 a multinational team of researchers from the University of Southern California, Delft University of Technology, the Iowa State University of Science and Technology, and the University of California, Santa Barbara, constructed a two-qubit quantum computer on a crystal of diamond doped with some manner of impurity, that can easily be scaled up in size and functionality at room temperature. Two logical qubit directions of electron spin and nitrogen kernels spin were used. A system which formed an impulse of microwave radiation of certain duration and the form was developed for maintenance of protection against decoherence. By means of this computer Grover's algorithm for four variants of search has generated the right answer from the first try in 95% of cases.[56]

In September 2012, Australian researchers at the University of New South Wales said the world's first quantum computer was just 5 to 10 years away, after announcing a global breakthrough enabling manufacture of its memory building blocks. A research team led by Australian engineers created the first working "quantum bit" based on a single atom in silicon, invoking the same technological platform that forms the building blocks of modern day computers, laptops and phones.[57] [58]

In October 2012, Nobel Prizes were presented to David J. Wineland and Serge Haroche for their basic work on understanding the quantum world - work which may eventually help make quantum computing possible.[59][60]

In November 2012, the first quantum teleportation from one macroscopic object to another was reported.[61][62]

In February 2013, a new technique Boson Sampling was reported by two groups using photons in an optical lattice that is not a universal quantum computer but which may be good enough for practical problems. Science Feb 15, 2013

In May 2013, Google Inc announced that it was launching the Quantum Artificial Intelligence Lab, to be hosted by NASA’s Ames Research Center. The lab will house a 512-qubit quantum computer from D-Wave Systems, and the USRA (Universities Space Research Association) will invite researchers from around the world to share time on it. The goal being to study how quantum computing might advance machine learning[63]

New Quantum Organic System on a the organic quantum computor level see the video new type of quantum computor on the rise is organic quantum system here take a look https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NyW1y39FTd4&feature=youtube_gdata_player

This veriation uses the solid state proccessing.

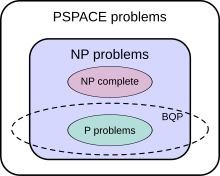

Relation to computational complexity theory

The class of problems that can be efficiently solved by quantum computers is called BQP, for "bounded error, quantum, polynomial time". Quantum computers only run probabilistic algorithms, so BQP on quantum computers is the counterpart of BPP ("bounded error, probabilistic, polynomial time") on classical computers. It is defined as the set of problems solvable with a polynomial-time algorithm, whose probability of error is bounded away from one half.[65] A quantum computer is said to "solve" a problem if, for every instance, its answer will be right with high probability. If that solution runs in polynomial time, then that problem is in BQP.

BQP is contained in the complexity class #P (or more precisely in the associated class of decision problems P#P),[66] which is a subclass of PSPACE.

BQP is suspected to be disjoint from NP-complete and a strict superset of P, but that is not known. Both integer factorization and discrete log are in BQP. Both of these problems are NP problems suspected to be outside BPP, and hence outside P. Both are suspected to not be NP-complete. There is a common misconception that quantum computers can solve NP-complete problems in polynomial time. That is not known to be true, and is generally suspected to be false.[66]

The capacity of a quantum computer to accelerate classical algorithms has rigid limits—upper bounds of quantum computation's complexity. The overwhelming part of classical calculations cannot be accelerated on a quantum computer.[67] A similar fact takes place for particular computational tasks, like the search problem, for which Grover's algorithm is optimal.[68]

Although quantum computers may be faster than classical computers, those described above can't solve any problems that classical computers can't solve, given enough time and memory (however, those amounts might be practically infeasible). A Turing machine can simulate these quantum computers, so such a quantum computer could never solve an undecidable problem like the halting problem. The existence of "standard" quantum computers does not disprove the Church–Turing thesis.[69] It has been speculated that theories of quantum gravity, such as M-theory or loop quantum gravity, may allow even faster computers to be built. Currently, defining computation in such theories is an open problem due to the problem of time, i.e. there currently exists no obvious way to describe what it means for an observer to submit input to a computer and later receive output.[70]

See also

- Chemical computer

- DNA computer

- Electronic quantum holography

- List of emerging technologies

- Natural computing

- Normal mode

- Photonic computing

- Post-quantum cryptography

- Quantum bus

- Quantum cognition

- Quantum gate

- Quantum threshold theorem

- Soliton

- Timeline of quantum computing

- Topological quantum computer

References

- ^ "Quantum Computing with Molecules" article in Scientific American by Neil Gershenfeld and Isaac L. Chuang

- ^ Manin, Yu. I. (1980). Vychislimoe i nevychislimoe (in Russian). Sov.Radio. pp. 13–15. Retrieved 4 March 2013.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ Feynman, R. P. (1982). "Simulating physics with computers". International Journal of Theoretical Physics. 21 (6): 467–488. doi:10.1007/BF02650179.

- ^ Deutsch, David (1992-01-06). "Quantum computation". Physics World.

- ^ Finkelstein, David (1969). "Space-Time Structure in High Energy Interactions". In Gudehus, T.; Kaiser, G. (eds.). Fundamental Interactions at High Energy. New York: Gordon & Breach.

- ^ New qubit control bodes well for future of quantum computing

- ^ Quantum Information Science and Technology Roadmap for a sense of where the research is heading.

- ^ Simon, D.R. (1994). "On the power of quantum computation". Foundations of Computer Science, 1994 Proceedings., 35th Annual Symposium on: 116–123. doi:10.1109/SFCS.1994.365701. ISBN 0-8186-6580-7.

- ^ Nielsen, Michael A. Quantum Computation and Quantum Information. p. 202.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Nielsen, Michael A. Quantum Computation and Quantum Information. p. 17.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Waldner, Jean-Baptiste (2007). Nanocomputers and Swarm Intelligence. London: ISTE. p. 157. ISBN 2-7462-1516-0.

- ^ a b David P. DiVincenzo (1995). "Quantum Computation". Science. 270 (5234): 255–261. Bibcode:1995Sci...270..255D. doi:10.1126/science.270.5234.255. (subscription required)

- ^ Arjen K. Lenstra (2000). "Integer Factoring" (PDF). Designs, Codes and Cryptography. 19 (2/3): 101–128. doi:10.1023/A:1008397921377.

- ^ a b Daniel J. Bernstein, Introduction to Post-Quantum Cryptography. Introduction to Daniel J. Bernstein, Johannes Buchmann, Erik Dahmen (editors). Post-quantum cryptography. Springer, Berlin, 2009. ISBN 978-3-540-88701-0

- ^ See also pqcrypto.org, a bibliography maintained by Daniel J. Bernstein and Tanja Lange on cryptography not known to be broken by quantum computing.

- ^ Robert J. McEliece. "A public-key cryptosystem based on algebraic coding theory." Jet Propulsion Laboratory DSN Progress Report 42–44, 114–116.

- ^ Kobayashi, H.; Gall, F.L. (2006). "Dihedral Hidden Subgroup Problem: A Survey". Information and Media Technologies. 1 (1): 178–185.

- ^ Bennett C.H., Bernstein E., Brassard G., Vazirani U., The strengths and weaknesses of quantum computation. SIAM Journal on Computing 26(5): 1510–1523 (1997).

- ^ Quantum Algorithm Zoo – Stephen Jordan's Homepage

- ^ The Father of Quantum Computing By Quinn Norton 02.15.2007, Wired.com

- ^ David P. DiVincenzo, IBM (2000-04-13). "The Physical Implementation of Quantum Computation". arXiv:quant-ph/0002077.

{{cite arXiv}}:|class=ignored (help) - ^ M. I. Dyakonov, Université Montpellier (2006-10-14). "Is Fault-Tolerant Quantum Computation Really Possible?". In: Future Trends in Microelectronics. Up the Nano Creek, S. Luryi, J. Xu, and A. Zaslavsky (eds), Wiley , pp.: 4–18. arXiv:quant-ph/0610117.

- ^ Freedman, Michael H.; Kitaev, Alexei; Larsen, Michael J.; Wang, Zhenghan (2003). "Topological quantum computation". Bulletin of the American Mathematical Society. 40 (1): 31–38. arXiv:quant-ph/0101025. doi:10.1090/S0273-0979-02-00964-3. MR 1943131.

- ^ Monroe, Don, Anyons: The breakthrough quantum computing needs?, New Scientist, 1 October 2008

- ^ Das, A.; Chakrabarti, B. K. (2008). "Quantum Annealing and Analog Quantum Computation". Rev. Mod. Phys. 80 (3): 1061–1081. doi:10.1103/RevModPhys.80.1061Template:Inconsistent citations

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ^ Nayak, Chetan; Simon, Steven; Stern, Ady; Das Sarma, Sankar (2008). "Nonabelian Anyons and Quantum Computation". Rev Mod Phys. 80 (3): 1083. arXiv:0707.1889. Bibcode:2008RvMP...80.1083N. doi:10.1103/RevModPhys.80.1083.

- ^ Clarke, John; Wilhelm, Frank (June 19, 2008). "Superconducting quantum bits". Nature. 453 (7198): 1031–1042. Bibcode:2008Natur.453.1031C. doi:10.1038/nature07128. PMID 18563154.

- ^ William M Kaminsky; Orlando (2004). "Scalable Superconducting Architecture for Adiabatic Quantum Computation". arXiv:quant-ph/0403090.

{{cite arXiv}}:|class=ignored (help); Missing|author2=(help) - ^ Imamoğlu, Atac; Awschalom, D. D.; Burkard, Guido; DiVincenzo, D. P.; Loss, D.; Sherwin, M.; Small, A. (1999). "Quantum information processing using quantum dot spins and cavity-QED". Physical Review Letters. 83 (20): 4204. Bibcode:1999PhRvL..83.4204I. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.83.4204.

- ^ Fedichkin, Leonid; Yanchenko, Maxim; Valiev, Kamil (2000). "Novel coherent quantum bit using spatial quantization levels in semiconductor quantum dot". Quantum Computers and Computing. 1: 58–76. arXiv:quant-ph/0006097. Bibcode:2000quant.ph..6097F.

- ^ Knill, G. J.; Laflamme, R.; Milburn, G. J. (2001). "A scheme for efficient quantum computation with linear optics". Nature. 409 (6816): 46–52. Bibcode:2001Natur.409...46K. doi:10.1038/35051009. PMID 11343107.

- ^ Nizovtsev; A. P.; et al. (October 19, 2004). "A quantum computer based on NV centers in diamond: Optically detected nutations of single electron and nuclear spins". Optics and Spectroscopy. 99 (2): 248–260. Bibcode:2005OptSp..99..233N. doi:10.1134/1.2034610.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|year=/|date=mismatch (help); Unknown parameter|author-separator=ignored (help) - ^ Wolfgang Gruener, TG Daily (2007-06-01). "Research indicates diamonds could be key to quantum storage". Retrieved 2007-06-04.

- ^ Neumann, P.; et al. (June 6, 2008). "Multipartite Entanglement Among Single Spins in Diamond". Science. 320 (5881): 1326–1329. Bibcode:2008Sci...320.1326N. doi:10.1126/science.1157233. PMID 18535240.

- ^ Rene Millman, IT PRO (2007-08-03). "Trapped atoms could advance quantum computing". Retrieved 2007-07-26.

- ^ Ohlsson, N.; Mohan, R. K.; Kröll, S. (January 1, 2002). "Quantum computer hardware based on rare-earth-ion-doped inorganic crystals". Opt. Commun. 201 (1–3): 71–77. Bibcode:2002OptCo.201...71O. doi:10.1016/S0030-4018(01)01666-2.

- ^ Longdell, J. J.; Sellars, M. J.; Manson, N. B. (September 23, 2004). "Demonstration of conditional quantum phase shift between ions in a solid". Phys. Rev. Lett. 93 (13): 130503. arXiv:quant-ph/0404083. Bibcode:2004PhRvL..93m0503L. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.93.130503. PMID 15524694.

- ^ Vandersypen, Lieven M. K.; Steffen, Matthias; Breyta, Gregory; Yannoni, Costantino S.; Sherwood, Mark H.; Chuang, Isaac L. (2001). "Experimental realization of Shor's quantum factoring algorithm using nuclear magnetic resonance". Nature. 414 (6866): 883–7. doi:10.1038/414883a. PMID 11780055.

- ^ Ann Arbor (2005-12-12). "U-M develops scalable and mass-producible quantum computer chip". Retrieved 2006-11-17.

- ^ L. DiCarlo, J. M. Chow, J. M. Gambetta, Lev S. Bishop, B. R. Johnson, D. I. Schuster, J. Majer, A. Blais, L. Frunzio, S. M. Girvin, R. J. Schoelkopf (2009-06-28). "Demonstration of two-qubit algorithms with a superconducting quantum processor" (PDF). Nature. 460 (7252): 240–4. Bibcode:2009Natur.460..240D. doi:10.1038/nature08121. PMID 19561592. Retrieved 2009-07-02.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Scientists Create First Electronic Quantum Processor". 2009-07-02. Retrieved 2009-07-02.

- ^ New Scientist (2009-09-04). "Code-breaking quantum algorithm runs on a silicon chip". Retrieved 2009-10-14.

- ^ "New Trends in Quantum Computation".

- ^ Quantum Information Processing. Springer.com. Retrieved on 2011-05-19.

- ^ "University of New South Wales".

- ^ "Engadget, First light wave quantum teleportation achieved, opens door to ultra fast data transmission".

- ^ "Learning to program the D-Wave One". Retrieved 11 May 2011.

- ^ "D-Wave Systems sells its first Quantum Computing System to Lockheed Martin Corporation". 2011-05-25. Retrieved 2011-05-30.

- ^ "Operational Quantum Computing Center Established at USC". 2011-10-29. Retrieved 2011-12-06.

- ^ Quantum annealing with manufactured spins Nature 473, 194–198, 12 May 2011

- ^ The CIA and Jeff Bezos Bet on Quantum Computing Technology Review October 4, 2012 by Tom Simonite

- ^ Enrique Martin Lopez, Anthony Laing, Thomas Lawson, Roberto Alvarez, Xiao-Qi Zhou, Jeremy L. O'Brien (2011). "Implementation of an iterative quantum order finding algorithm". Nature Photonics. 6 (11): 773–776. arXiv:1111.4147. doi:10.1038/nphoton.2012.259.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Quantum computer with Von Neumann architecture

- ^ Quantum Factorization of 143 on a Dipolar-Coupling NMR system

- ^ IBM Says It's 'On the Cusp' of Building a Quantum Computer

- ^ Quantum computer built inside diamond

- ^ "Australian engineers write quantum computer 'qubit' in global breakthrough". The Australian. Retrieved 3 October 2012.

- ^ "Breakthrough in bid to create first quantum computer". The University of New South Wales. Retrieved 3 October 2012.

- ^ Frank, Adam (October 14, 2012). "Cracking the Quantum Safe". New York Times. Retrieved October 14, 2012.

- ^ Overbye, Dennis (October 9, 2012). "A Nobel for Teasing Out the Secret Life of Atoms". New York Times. Retrieved October 14, 2012.

- ^ The Physics arXiv Blog (November 15, 2012). "First Teleportation from One Macroscopic Object to Another". MIT Technology Review. Retrieved November 17, 2012.

- ^ Bao, Xiao-Hui; Xu, Xiao-Fan; Li, Che-Ming; Yuan, Zhen-Sheng; Lu, Chao-Yang; Pan, Jian-wei (November 13, 2012). "Quantum teleportation between remote atomic-ensemble quantum memories". arXiv. arXiv:1211.2892.

- ^ "Launching the Quantum Artificial Intelligence Lab". Research@Google Blog. Retrieved 16 May 2013.

- ^ Nielsen, p. 42

- ^ Nielsen, p. 41

- ^ a b Bernstein, Ethan; Vazirani, Umesh (1997). "Quantum Complexity Theory". SIAM Journal on Computing. 26 (5): 1411. doi:10.1137/S0097539796300921.

- ^ Ozhigov, Yuri (1999). "Quantum Computers Speed Up Classical with Probability Zero". Chaos Solitons Fractals. 10 (10): 1707–1714. arXiv:quant-ph/9803064. Bibcode:1998quant.ph..3064O. doi:10.1016/S0960-0779(98)00226-4.

- ^ Ozhigov, Yuri (1999). "Lower Bounds of Quantum Search for Extreme Point". Proc.Roy.Soc.Lond. A455 (1986): 2165–2172. arXiv:quant-ph/9806001. Bibcode:1999RSPSA.455.2165O. doi:10.1098/rspa.1999.0397.

- ^ Nielsen, p. 126

- ^ Scott Aaronson, NP-complete Problems and Physical Reality, ACM SIGACT News, Vol. 36, No. 1. (March 2005), pp. 30–52, section 7 "Quantum Gravity": "[...] to anyone who wants a test or benchmark for a favorite quantum gravity theory,[author's footnote: That is, one without all the bother of making numerical predictions and comparing them to observation] let me humbly propose the following: can you define Quantum Gravity Polynomial-Time? [...] until we can say what it means for a ‘user’ to specify an ‘input’ and ‘later’ receive an ‘output’—there is no such thing as computation, not even theoretically." (emphasis in original)

Bibliography

- Nielsen, Michael and Chuang, Isaac (2000). Quantum Computation and Quantum Information. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-63503-9. OCLC 174527496.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

General references

- Derek Abbott, Charles R. Doering, Carlton M. Caves, Daniel M. Lidar, Howard E. Brandt, Alexander R. Hamilton, David K. Ferry, Julio Gea-Banacloche, Sergey M. Bezrukov, and Laszlo B. Kish (2003). "Dreams versus Reality: Plenary Debate Session on Quantum Computing". Quantum Information Processing. 2 (6): 449–472. arXiv:quant-ph/0310130. doi:10.1023/B:QINP.0000042203.24782.9a. hdl:2027.42/45526.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - David P. DiVincenzo (2000). "The Physical Implementation of Quantum Computation". Experimental Proposals for Quantum Computation. arXiv:quant-ph/0002077

- David P. DiVincenzo (1995). "Quantum Computation". Science. 270 (5234): 255–261. Bibcode:1995Sci...270..255D. doi:10.1126/science.270.5234.255. Table 1 lists switching and dephasing times for various systems.

- Richard Feynman (1982). "Simulating physics with computers". International Journal of Theoretical Physics. 21 (6–7): 467. Bibcode:1982IJTP...21..467F. doi:10.1007/BF02650179.

- Gregg Jaeger (2006). Quantum Information: An Overview. Berlin: Springer. ISBN 0-387-35725-4. OCLC 255569451.

- Stephanie Frank Singer (2005). Linearity, Symmetry, and Prediction in the Hydrogen Atom. New York: Springer. ISBN 0-387-24637-1. OCLC 253709076.

- Giuliano Benenti (2004). Principles of Quantum Computation and Information Volume 1. New Jersey: World Scientific. ISBN 981-238-830-3. OCLC 179950736.

- Sam Lomonaco Four Lectures on Quantum Computing given at Oxford University in July 2006

- C. Adami, N.J. Cerf. (1998). "Quantum computation with linear optics". arXiv:quant-ph/9806048v1.

- Joachim Stolze, (2004). Quantum Computing. Wiley-VCH. ISBN 3-527-40438-4.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link)

- Ian Mitchell, (1998). "Computing Power into the 21st Century: Moore's Law and Beyond".

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link)

- Rolf Landauer, (1961). "Irreversibility and heat generation in the computing process" (PDF).

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link)

- Gordon E. Moore (1965). Cramming more components onto integrated circuits.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help)

- R.W. Keyes, (1988). Miniaturization of electronics and its limits.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help)CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link)

- M. A. Nielsen,. "Complete Quantum Teleportation By Nuclear Magnetic Resonance".

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link)

- Lieven M.K. Vandersypen, (2000). Liquid state NMR Quantum Computing.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link)

- Imai Hiroshi, (2006). Quantum Computation and Information. Berlin: Springer. ISBN 3-540-33132-8.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link)

- Andre Berthiaume, (1997). "Quantum Computation".

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link)

- Daniel R. Simon, (1994). "On the Power of Quantum Computation". Institute of Electrical and Electronic Engineers Computer Society Press.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link)

- "Seminar Post Quantum Cryptology". Chair for communication security at the Ruhr-University Bochum.

- Laura Sanders, (2009). "First programmable quantum computer created".

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - "New trends in quantum computation".

External links

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy: "Quantum Computing" by Amit Hagar.

- Quantiki – Wiki and portal with free-content related to quantum information science.

- Scott Aaronson's blog, which features informative and critical commentary on developments in the field

- Lectures

- Quantum Mechanics and Quantum Computation — Coursera course by Umesh Vazirani

- Quantum computing for the determined — 22 video lectures by Michael Nielsen

- Video Lectures by David Deutsch

- Lectures at the Institut Henri Poincaré (slides and videos)

- Online lecture on An Introduction to Quantum Computing, Edward Gerjuoy (2008)

- Quantum Computing research by Mikko Möttönen at Aalto University (video)