Hepatitis B: Difference between revisions

→Prevention: updated / added / simplified |

→Epidemiology: added |

||

| Line 127: | Line 127: | ||

[[File:Hepatitis B world map - DALY - WHO2004.svg|thumb|Estimate of [[disability-adjusted life year]] for hepatitis B per 100,000 inhabitants as of 2004. |

[[File:Hepatitis B world map - DALY - WHO2004.svg|thumb|Estimate of [[disability-adjusted life year]] for hepatitis B per 100,000 inhabitants as of 2004. |

||

{{Multicol}} |

{{Multicol}} |

||

{{legend|#b3b3b3|no data}} |

{{legend|#b3b3b3|no data}} |

||

{{legend|#ffff65|<10}} |

{{legend|#ffff65|<10}} |

||

| Line 145: | Line 144: | ||

]] |

]] |

||

[[File:HBV prevalence 2005.png|thumb|Prevalence of hepatitis B virus as of 2005.]] |

[[File:HBV prevalence 2005.png|thumb|Prevalence of hepatitis B virus as of 2005.]] |

||

In 2004, an estimated 350 million individuals were infected worldwide. National and regional prevalence ranges from over 10% in Asia to under 0.5% in the United States and northern Europe. |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

Routes of infection include vertical transmission (such as through childbirth), early life horizontal transmission (bites, lesions, and sanitary habits), and adult horizontal transmission (sexual contact, intravenous drug use).<ref>{{cite journal|last=Custer|first=B|coauthors=Sullivan, SD; Hazlet, TK; Iloeje, U; Veenstra, DL; Kowdley, KV|title=Global epidemiology of hepatitis B virus.|journal=Journal of clinical gastroenterology|date=2004 Nov-Dec|volume=38|issue=10 Suppl 3|pages=S158-68|pmid=15602165}}</ref> |

|||

| ⚫ | The primary method of transmission reflects the prevalence of chronic HBV infection in a given area. In low prevalence areas such as the continental United States and Western Europe, injection drug abuse and unprotected sex are the primary methods, although other factors may also be important.<ref>{{Cite doi|10.1086/513435}}</ref> In moderate prevalence areas, which include Eastern Europe, Russia, and Japan, where 2–7% of the population is chronically infected, the disease is predominantly spread among children. In high-prevalence areas such as [[Hepatitis B in China|China]] and South East Asia, transmission during childbirth is most common, although in other areas of high endemicity such as Africa, transmission during childhood is a significant factor.<ref name="pmid12616449">{{Cite doi|10.1055/s-2003-37583}}</ref> The prevalence of chronic HBV infection in areas of high endemicity is at least 8% with 10-15% prevalence in Africa/Far East.<ref name="pmid23800310">{{cite journal|last=Komas|first=Narcisse P|coauthors=Vickos, Ulrich; Hübschen, Judith M; Béré, Aubin; Manirakiza, Alexandre; Muller, Claude P; Le Faou, Alain|title=Cross-sectional study of hepatitis B virus infection in rural communities, Central African Republic|journal=BMC Infectious Diseases|date=1 January 2013|volume=13|pages=286|doi=10.1186/1471-2334-13-286|pmid=23800310|url=http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2334/13/286|pmc=3694350}}</ref> As of 2010, China has 120 million infected people, followed by India and Indonesia with 40 million and 12 million, respectively. According to [[World Health Organization]] (WHO), an estimated 600,000 people die every year related to the infection.<ref>{{cite news |title=Healthcare stumbling in RI's Hepatitis fight |url=http://www.thejakartapost.com/news/2011/01/13/healthcare-stumbling-ri’s-hepatitis-fight.html |work=[[The Jakarta Post]] |date=2011-01-13 }}</ref> |

||

In the United States about 19,000 new cases occurred in 2011 down nearly 90% from 1990.<ref name=CDC2013/> |

|||

==History== |

==History== |

||

Revision as of 20:05, 23 December 2013

| Hepatitis B | |

|---|---|

| Specialty | Infectious diseases |

Hepatitis B is an infectious illness of the liver caused by the hepatitis B virus (HBV) that affects hominoidea, including humans. Originally known as "serum hepatitis",[1] the disease has caused epidemics in parts of Asia and Africa, and it is endemic in China.[2] About a third of the world population has been infected at one point in their lives,[3] including 350 million who are chronic carriers.[4]

The virus is transmitted by exposure to infectious blood or body fluids such as semen and vaginal fluids, while viral DNA has been detected in the saliva, tears, and urine of chronic carriers. Perinatal infection is a major route of infection in endemic (mainly developing) countries.[5] Other risk factors for developing HBV infection include working in a healthcare setting, transfusions, dialysis, acupuncture, tattooing, sharing razors or toothbrushes with an infected person, travel in countries where it is endemic, and residence in an institution.[3][6][7][8] However, hepatitis B viruses cannot be spread by holding hands, sharing eating utensils or drinking glasses, kissing, hugging, coughing, sneezing, or breastfeeding.[8][9]

The acute illness causes liver inflammation, vomiting, jaundice, and, rarely, death. Chronic hepatitis B may eventually cause cirrhosis and liver cancer—a disease with poor response to all but a few current therapies.[10] The infection is preventable by vaccination.[11]

Hepatitis B virus is a hepadnavirus—hepa from hepatotropic (attracted to the liver) and dna because it is a DNA virus[12]—and it has a circular genome of partially double-stranded DNA. The viruses replicate through an RNA intermediate form by reverse transcription, which in practice relates them to retroviruses.[13] Although replication takes place in the liver, the virus spreads to the blood where viral proteins and antibodies against them are found in infected people.[14] The hepatitis B virus is 50 to 100 times more infectious than HIV.[15][failed verification]

Signs and symptoms

Acute infection with hepatitis B virus is associated with acute viral hepatitis – an illness that begins with general ill-health, loss of appetite, nausea, vomiting, body aches, mild fever, and dark urine, and then progresses to development of jaundice. It has been noted that itchy skin has been an indication as a possible symptom of all hepatitis virus types. The illness lasts for a few weeks and then gradually improves in most affected people. A few people may have more severe liver disease (fulminant hepatic failure), and may die as a result. The infection may be entirely asymptomatic and may go unrecognized.[16]

Chronic infection with hepatitis B virus either may be asymptomatic or may be associated with a chronic inflammation of the liver (chronic hepatitis), leading to cirrhosis over a period of several years. This type of infection dramatically increases the incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma (liver cancer). Across Europe hepatitis B and C cause approximately 50% hepatocellular carcinomas.[17][18] Chronic carriers are encouraged to avoid consuming alcohol as it increases their risk for cirrhosis and liver cancer. Hepatitis B virus has been linked to the development of membranous glomerulonephritis (MGN).[19]

Symptoms outside of the liver are present in 1–10% of HBV-infected people and include serum-sickness–like syndrome, acute necrotizing vasculitis (polyarteritis nodosa), membranous glomerulonephritis, and papular acrodermatitis of childhood (Gianotti–Crosti syndrome).[20][21] The serum-sickness–like syndrome occurs in the setting of acute hepatitis B, often preceding the onset of jaundice.[22] The clinical features are fever, skin rash, and polyarteritis. The symptoms often subside shortly after the onset of jaundice, but can persist throughout the duration of acute hepatitis B.[23] About 30–50% of people with acute necrotizing vasculitis (polyarteritis nodosa) are HBV carriers.[24] HBV-associated nephropathy has been described in adults but is more common in children.[25][26] Membranous glomerulonephritis is the most common form.[23] Other immune-mediated hematological disorders, such as essential mixed cryoglobulinemia and aplastic anemia.[23]

Virology

Structure

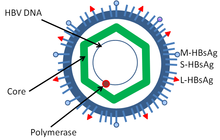

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) is a member of the hepadnavirus family.[12] The virus particle (virion) consists of an outer lipid envelope and an icosahedral nucleocapsid core composed of protein. These virions are 30-42 nm in diameter. The nucleocapsid encloses the viral DNA and a DNA polymerase that has reverse transcriptase activity.[13] The outer envelope contains embedded proteins that are involved in viral binding of, and entry into, susceptible cells. The virus is one of the smallest enveloped animal viruses, and the 42 nM virions, which are capable of infecting hepatocytes, are referred to as "Dane particles".[27] In addition to the Dane particles, filamentous and spherical bodies lacking a core can be found in the serum of infected individuals. These particles are not infectious and are composed of the lipid and protein that forms part of the surface of the virion, which is called the surface antigen (HBsAg), and is produced in excess during the life cycle of the virus.[28]

Genome

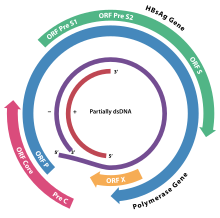

The genome of HBV is made of circular DNA, but it is unusual because the DNA is not fully double-stranded. One end of the full length strand is linked to the viral DNA polymerase. The genome is 3020–3320 nucleotides long (for the full-length strand) and 1700–2800 nucleotides long (for the short length-strand).[29] The negative-sense (non-coding) is complementary to the viral mRNA. The viral DNA is found in the nucleus soon after infection of the cell. The partially double-stranded DNA is rendered fully double-stranded by completion of the (+) sense strand and removal of a protein molecule from the (-) sense strand and a short sequence of RNA from the (+) sense strand. Non-coding bases are removed from the ends of the (-) sense strand and the ends are rejoined. There are four known genes encoded by the genome, called C, X, P, and S. The core protein is coded for by gene C (HBcAg), and its start codon is preceded by an upstream in-frame AUG start codon from which the pre-core protein is produced. HBeAg is produced by proteolytic processing of the pre-core protein. The DNA polymerase is encoded by gene P. Gene S is the gene that codes for the surface antigen (HBsAg). The HBsAg gene is one long open reading frame but contains three in frame "start" (ATG) codons that divide the gene into three sections, pre-S1, pre-S2, and S. Because of the multiple start codons, polypeptides of three different sizes called large, middle, and small (pre-S1 + pre-S2 + S, pre-S2 + S, or S) are produced.[30] The function of the protein coded for by gene X is not fully understood but it is associated with the development of liver cancer. It stimulates genes that promote cell growth and inactivates growth regulating molecules.[31]

Replication

The life cycle of hepatitis B virus is complex. Hepatitis B is one of a few known pararetroviruses: non-retroviruses that still use reverse transcription in their replication process. The virus gains entry into the cell by binding to NTCP [32] on the surface and being endocytosed. Because the virus multiplies via RNA made by a host enzyme, the viral genomic DNA has to be transferred to the cell nucleus by host proteins called chaperones. The partially double stranded viral DNA is then made fully double stranded and transformed into covalently closed circular DNA (cccDNA) that serves as a template for transcription of four viral mRNAs. The largest mRNA, (which is longer than the viral genome), is used to make the new copies of the genome and to make the capsid core protein and the viral DNA polymerase. These four viral transcripts undergo additional processing and go on to form progeny virions that are released from the cell or returned to the nucleus and re-cycled to produce even more copies.[30][33] The long mRNA is then transported back to the cytoplasm where the virion P protein (the DNA polymerase) synthesizes DNA via its reverse transcriptase activity.

Serotypes and genotypes

The virus is divided into four major serotypes (adr, adw, ayr, ayw) based on antigenic epitopes presented on its envelope proteins, and into eight genotypes (A-H) according to overall nucleotide sequence variation of the genome. The genotypes have a distinct geographical distribution and are used in tracing the evolution and transmission of the virus. Differences between genotypes affect the disease severity, course and likelihood of complications, and response to treatment and possibly vaccination.[34][35]

Genotypes differ by at least 8% of their sequence and were first reported in 1988 when six were initially described (A-F).[36] Two further types have since been described (G and H).[37] Most genotypes are now divided into subgenotypes with distinct properties.[38]

- Distribution of genotypes

Genotype A is most commonly found in the Americas, Africa, India and Western Europe. It is divided into subgenotypes. Of these subgenotype A1 is further subdivided into an Asian and an African clade.

Genotype B is most commonly found in Asia and the United States. Genotype B1 dominates in Japan, B2 in China and Vietnam while B3 confined to Indonesia. B4 is confined to Vietnam. All these strains specify the serotype ayw1. B5 is most common in the Philippines.

Genotype C is most common in Asia and the United States. Subgenotype C1 is common in Japan, Korea and China. C2 is common in China, South-East Asia and Bangladesh and C3 in Oceania. All these strains specify the serotype adr. C4 specifying ayw3 is found in Aborigines from Australia.[39]

Genotype D is most commonly found in Southern Europe, India and the United States and has been divided into 8 subtypes (D1–D8). In Turkey genotype D is also the most common type. A pattern of defined geographical distribution is less evident with D1–D4 where these subgenotypes are widely spread within Europe, Africa and Asia. This may be due to their divergence having occurred before that of genotypes B and C. D4 appears to be the oldest split and is still the dominating subgenotype of D in Oceania.

Type E is most commonly found in West and Southern Africa.

Type F is most commonly found in Central and South America and has been divided into two subgroups (F1 and F2).

Genotype G has an insertion of 36 nucleotides in the core gene and is found in France and the United States.[40]

Type H is most commonly found in Central and South America and California in United States.

Africa has five genotypes (A-E). Of these the predominant genotypes are A in Kenya, B and D in Egypt, D in Tunisia, A-D in South Africa and E in Nigeria.[39] Genotype H is probably split off from genotype F within the New World.[41]

- Evolution

A Bayesian analysis of the genotypes suggests that the rate of evolution of the core protein gene is 1.127 (95% credible interval 0.925-1.329) substitutions per site per year.[42]

The most recent common ancestor of genotypes A, B, D evolved in 1895 (95% confidence interval 1819-1959), 1829 (95% confidence interval 1690-1935) and 1880 (95% confidence interval 1783-1948) respectively.[42]

Mechanisms

Pathogenesis

Hepatitis B virus primarily interferes with the functions of the liver by replicating in liver cells, known as hepatocytes. A functional receptor is NTCP.[32] There is evidence that the receptor in the closely related duck hepatitis B virus is carboxypeptidase D.[43][44] The virions bind to the host cell via the preS domain of the viral surface antigen and are subsequently internalized by endocytosis. HBV-preS-specific receptors are expressed primarily on hepatocytes; however, viral DNA and proteins have also been detected in extrahepatic sites, suggesting that cellular receptors for HBV may also exist on extrahepatic cells.[45]

During HBV infection, the host immune response causes both hepatocellular damage and viral clearance. Although the innate immune response does not play a significant role in these processes, the adaptive immune response, in particular virus-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes(CTLs), contributes to most of the liver injury associated with HBV infection. CTLs eliminate HBV infection by killing infected cells and producing antiviral cytokines, which are then used to purge HBV from viable hepatocytes.[46] Although liver damage is initiated and mediated by the CTLs, antigen-nonspecific inflammatory cells can worsen CTL-induced immunopathology, and platelets activated at the site of infection may facilitate the accumulation of CTLs in the liver.[47]

Transmission

Transmission of hepatitis B virus results from exposure to infectious blood or body fluids containing blood. Possible forms of transmission include sexual contact,[48] blood transfusions and transfusion with other human blood products,[49] re-use of contaminated needles and syringes,[50] and vertical transmission from mother to child (MTCT) during childbirth. Without intervention, a mother who is positive for HBsAg confers a 20% risk of passing the infection to her offspring at the time of birth. This risk is as high as 90% if the mother is also positive for HBeAg. HBV can be transmitted between family members within households, possibly by contact of nonintact skin or mucous membrane with secretions or saliva containing HBV.[51] However, at least 30% of reported hepatitis B among adults cannot be associated with an identifiable risk factor.[52] And Shi et al. showed that breastfeeding after proper immunoprophylaxis did not contribute to MTCT of HBV.[53]

Diagnosis

The tests, called assays, for detection of hepatitis B virus infection involve serum or blood tests that detect either viral antigens (proteins produced by the virus) or antibodies produced by the host. Interpretation of these assays is complex.[54]

The hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) is most frequently used to screen for the presence of this infection. It is the first detectable viral antigen to appear during infection. However, early in an infection, this antigen may not be present and it may be undetectable later in the infection as it is being cleared by the host. The infectious virion contains an inner "core particle" enclosing viral genome. The icosahedral core particle is made of 180 or 240 copies of core protein, alternatively known as hepatitis B core antigen, or HBcAg. During this 'window' in which the host remains infected but is successfully clearing the virus, IgM antibodies to the hepatitis B core antigen (anti-HBc IgM) may be the only serological evidence of disease. Therefore most hepatitis B diagnostic panels contain HBsAg and total anti-HBc (both IgM and IgG).[55]

Shortly after the appearance of the HBsAg, another antigen called hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg) will appear. Traditionally, the presence of HBeAg in a host's serum is associated with much higher rates of viral replication and enhanced infectivity; however, variants of the hepatitis B virus do not produce the 'e' antigen, so this rule does not always hold true.[56] During the natural course of an infection, the HBeAg may be cleared, and antibodies to the 'e' antigen (anti-HBe) will arise immediately afterwards. This conversion is usually associated with a dramatic decline in viral replication.

If the host is able to clear the infection, eventually the HBsAg will become undetectable and will be followed by IgG antibodies to the hepatitis B surface antigen and core antigen (anti-HBs and anti HBc IgG).[12] The time between the removal of the HBsAg and the appearance of anti-HBs is called the window period. A person negative for HBsAg but positive for anti-HBs either has cleared an infection or has been vaccinated previously.

Individuals who remain HBsAg positive for at least six months are considered to be hepatitis B carriers.[57] Carriers of the virus may have chronic hepatitis B, which would be reflected by elevated serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels and inflammation of the liver, as revealed by biopsy. Carriers who have seroconverted to HBeAg negative status, in particular those who acquired the infection as adults, have very little viral multiplication and hence may be at little risk of long-term complications or of transmitting infection to others.[58]

PCR tests have been developed to detect and measure the amount of HBV DNA, called the viral load, in clinical specimens. These tests are used to assess a person's infection status and to monitor treatment.[59] Individuals with high viral loads, characteristically have ground glass hepatocytes on biopsy.

Prevention

Vaccines for the prevention of hepatitis B have been routinely recommended for infants since 1991 in the United States.[60] Most vaccines are given in three doses over a course of months. A protective response to the vaccine is defined as an anti-HBs antibody concentration of at least 10 mIU/ml in the recipient's serum. The vaccine is more effective in children and 95 per cent of those vaccinated have protective levels of antibody. This drops to around 90% at 40 years of age and to around 75 percent in those over 60 years. The protection afforded by vaccination is long lasting even after antibody levels fall below 10 mIU/ml. Vaccination at birth is recommended for all infants of HBV infected mothers. A combination of hepatitis B immunoglobulin and an accelerated course of HBV vaccine prevents perinatal HBV transmission in around 90% of cases.[61]

All those with a risk of exposure to body fluids such as blood should be vaccinated, if not already.[60] Testing to verify effective immunization is recommended and further doses of vaccine are given to those who are not sufficiently immunized.[60]

In assisted reproductive technology, sperm washing is not necessary for males with hepatitis B to prevent transmission, unless the female partner has not been effectively vaccinated.[62] In females with hepatitis B, the risk of transmission from mother to child with IVF is no different from the risk in spontaneous conception.[62]

Treatment

The hepatitis B infection does not usually require treatment because most adults clear the infection spontaneously.[63] Early antiviral treatment may be required in fewer than 1% of people, whose infection takes a very aggressive course (fulminant hepatitis) or who are immunocompromised. On the other hand, treatment of chronic infection may be necessary to reduce the risk of cirrhosis and liver cancer. Chronically infected individuals with persistently elevated serum alanine aminotransferase, a marker of liver damage, and HBV DNA levels are candidates for therapy.[64] Treatment lasts from six months to a year, depending on medication and genotype.[65]

Although none of the available drugs can clear the infection, they can stop the virus from replicating, thus minimizing liver damage. As of 2008, there are seven medications licensed for treatment of hepatitis B infection in the United States. These include antiviral drugs lamivudine (Epivir), adefovir (Hepsera), tenofovir (Viread), telbivudine (Tyzeka) and entecavir (Baraclude), and the two immune system modulators interferon alpha-2a and PEGylated interferon alpha-2a (Pegasys). The use of interferon, which requires injections daily or thrice weekly, has been supplanted by long-acting PEGylated interferon, which is injected only once weekly.[66] However, some individuals are much more likely to respond than others, and this might be because of the genotype of the infecting virus or the person's heredity. The treatment reduces viral replication in the liver, thereby reducing the viral load (the amount of virus particles as measured in the blood).[67] Response to treatment differs between the genotypes. Interferon treatment may produce an e antigen seroconversion rate of 37% in genotype A but only a 6% seroconversion in type D. Genotype B has similar seroconversion rates to type A while type C seroconverts only in 15% of cases. Sustained e antigen loss after treatment is ~45% in types A and B but only 25–30% in types C and D.[68]

Prognosis

Hepatitis B virus infection may be either acute (self-limiting) or chronic (long-standing). Persons with self-limiting infection clear the infection spontaneously within weeks to months.

Children are less likely than adults to clear the infection. More than 95% of people who become infected as adults or older children will stage a full recovery and develop protective immunity to the virus. However, this drops to 30% for younger children, and only 5% of newborns that acquire the infection from their mother at birth will clear the infection.[69][dead link] This population has a 40% lifetime risk of death from cirrhosis or hepatocellular carcinoma.[66] Of those infected between the age of one to six, 70% will clear the infection.[70]

Hepatitis D (HDV) can occur only with a concomitant hepatitis B infection, because HDV uses the HBV surface antigen to form a capsid.[71] Co-infection with hepatitis D increases the risk of liver cirrhosis and liver cancer.[72] Polyarteritis nodosa is more common in people with hepatitis B infection.

Reactivation

Hepatitis B virus DNA persists in the body after infection, and in some people the disease recurs.[73] Although rare, reactivation is seen most often following alcohol or drug use,[74] or in people with impaired immunity.[75] HBV goes through cycles of replication and non-replication. Approximately 50% of overt carriers experience acute reactivation. Males with baseline ALT of 200 UL/L are three times more likely to develop a reactivation than people with lower levels. Although reactivation can occur spontaneously,[76] people who undergo chemotherapy have a higher risk.[77] Immunosuppressive drugs favor increased HBV replication while inhibiting cytotoxic T cell function in the liver.[78][dead link] The risk of reactivation varies depending on the serological profile; those with detectable HBsAg in their blood are at the greatest risk, but those with only antibodies to the core antigen are also at risk. The presence of antibodies to the surface antigen, which are considered to be a marker of immunity, does not preclude reactivation.[77] Treatment with prophylactic antiviral drugs can prevent the serious morbidity associated with HBV disease reactivation.[77]

Epidemiology

In 2004, an estimated 350 million individuals were infected worldwide. National and regional prevalence ranges from over 10% in Asia to under 0.5% in the United States and northern Europe.

Routes of infection include vertical transmission (such as through childbirth), early life horizontal transmission (bites, lesions, and sanitary habits), and adult horizontal transmission (sexual contact, intravenous drug use).[79]

The primary method of transmission reflects the prevalence of chronic HBV infection in a given area. In low prevalence areas such as the continental United States and Western Europe, injection drug abuse and unprotected sex are the primary methods, although other factors may also be important.[80] In moderate prevalence areas, which include Eastern Europe, Russia, and Japan, where 2–7% of the population is chronically infected, the disease is predominantly spread among children. In high-prevalence areas such as China and South East Asia, transmission during childbirth is most common, although in other areas of high endemicity such as Africa, transmission during childhood is a significant factor.[81] The prevalence of chronic HBV infection in areas of high endemicity is at least 8% with 10-15% prevalence in Africa/Far East.[82] As of 2010, China has 120 million infected people, followed by India and Indonesia with 40 million and 12 million, respectively. According to World Health Organization (WHO), an estimated 600,000 people die every year related to the infection.[83]

In the United States about 19,000 new cases occurred in 2011 down nearly 90% from 1990.[60]

History

The earliest record of an epidemic caused by hepatitis B virus was made by Lurman in 1885.[84] An outbreak of smallpox occurred in Bremen in 1883 and 1,289 shipyard employees were vaccinated with lymph from other people. After several weeks, and up to eight months later, 191 of the vaccinated workers became ill with jaundice and were diagnosed as suffering from serum hepatitis. Other employees who had been inoculated with different batches of lymph remained healthy. Lurman's paper, now regarded as a classical example of an epidemiological study, proved that contaminated lymph was the source of the outbreak. Later, numerous similar outbreaks were reported following the introduction, in 1909, of hypodermic needles that were used, and, more importantly, reused, for administering Salvarsan for the treatment of syphilis. The virus was not discovered until 1966 when Baruch Blumberg, then working at the National Institutes of Health (NIH), discovered the Australia antigen (later known to be hepatitis B surface antigen, or HBsAg) in the blood of Australian aboriginal people.[85] Although a virus had been suspected since the research published by MacCallum in 1947,[86] D.S. Dane and others discovered the virus particle in 1970 by electron microscopy.[87] By the early 1980s the genome of the virus had been sequenced,[88] and the first vaccines were being tested.[89]

Society and culture

World Hepatitis Day, observed July 28, aims to raise global awareness of hepatitis B and hepatitis C and encourage prevention, diagnosis and treatment. It has been led by the World Hepatitis Alliance since 2007 and in May 2010, it got global endorsement from the World Health Organization.[90]

References

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1001/jama.276.10.841, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1001/jama.276.10.841instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1002/hep.21347, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1002/hep.21347instead. - ^ a b "Hepatitis B". World Health Organization (WHO). Retrieved 19 September 2009.

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 23622604, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=23622604instead. - ^ Coopstead, Lee-Ellen C. (2010). Pathophysiology. Missouri: Saunders. pp. 886–887. ISBN 978-1-4160-5543-3.

- ^ Sleisenger, MH (2006). Fordtran's gastrointestinal and liver disease: pathophysiology, diagnosis, management (8th ed.). Philadelphia: Saunders.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Kidd-Ljunggren K, Holmberg A, Bläckberg J, Lindqvist B (2006). "High levels of hepatitis B virus DNA in body fluids from chronic carriers". The Journal of Hospital Infection. 64 (4): 352–7. doi:10.1016/j.jhin.2006.06.029. PMID 17046105.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b "Hepatitis B FAQs for the Public — Transmission". U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Retrieved 29 November 2011.

- ^ "Hepatitis B". National Institute of Health. Retrieved 23 November 2010.

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1016/j.siny.2007.01.013, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1016/j.siny.2007.01.013instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.4065/82.8.967, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.4065/82.8.967instead. - ^ a b c Zuckerman AJ (1996). "Hepatitis Viruses". In Baron S; et al. (eds.). Baron's Medical Microbiology (4th ed.). University of Texas Medical Branch. ISBN 0-9631172-1-1.

{{cite book}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|editor=(help) - ^ a b Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1055/s-2004-828672, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1055/s-2004-828672instead. - ^ Hepatitis B Foundation: Blood Test FAQ

- ^ http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs204/en/

- ^ Terrault N, Roche B, Samuel D (2005). "Management of the hepatitis B virus in the liver transplantation setting: a European and an American perspective". Liver Transpl. 11 (7): 716–32. doi:10.1002/lt.20492. PMID 15973718.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ El-Serag, HB (June 2007). "Hepatocellular carcinoma: epidemiology and molecular carcinogenesis". Gastroenterology. 132 (7): 2557–76. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2007.04.061. PMID 17570226.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ El-Serag, Hashem B. (22 September 2011). "Hepatocellular carcinoma". New England Journal of Medicine. 365 (12): 1118–1127. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1001683. PMID 21992124.

- ^ Gan SI, Devlin SM, Scott-Douglas NW, Burak KW (2005). "Lamivudine for the treatment of membranous glomerulopathy secondary to chronic hepatitis B infection". Canadian journal of gastroenterology = Journal canadien de gastroenterologie. 19 (10): 625–9. PMID 16247526.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Dienstag JL (1981). "Hepatitis B as an immune complex disease". Seminars in Liver Disease. 1 (1): 45–57. doi:10.1055/s-2008-1063929. PMID 6126007.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Trepo C, Guillevin L (2001). "Polyarteritis nodosa and extrahepatic manifestations of HBV infection: the case against autoimmune intervention in pathogenesis". Journal of Autoimmunity. 16 (3): 269–74. doi:10.1006/jaut.2000.0502. PMID 11334492.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Alpert E, Isselbacher KJ, Schur PH (1971). "The pathogenesis of arthritis associated with viral hepatitis. Complement-component studies". The New England Journal of Medicine. 285 (4): 185–9. doi:10.1056/NEJM197107222850401. PMID 4996611.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c Liang TJ (2009). "Hepatitis B: the virus and disease". Hepatology (Baltimore, Md.). 49 (5 Suppl): S13–21. doi:10.1002/hep.22881. PMC 2809016. PMID 19399811.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Gocke DJ, Hsu K, Morgan C, Bombardieri S, Lockshin M, Christian CL (1970). "Association between polyarteritis and Australia antigen". Lancet. 2 (7684): 1149–53. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(70)90339-9. PMID 4098431.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Lai KN, Li PK, Lui SF; et al. (1991). "Membranous nephropathy related to hepatitis B virus in adults". The New England Journal of Medicine. 324 (21): 1457–63. doi:10.1056/NEJM199105233242103. PMID 2023605.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Takekoshi Y, Tanaka M, Shida N, Satake Y, Saheki Y, Matsumoto S (1978). "Strong association between membranous nephropathy and hepatitis-B surface antigenaemia in Japanese children". Lancet. 2 (8099): 1065–8. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(78)91801-9. PMID 82085.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Harrison T (2009). Desk Encyclopedia of General Virology. Boston: Academic Press. p. 455. ISBN 0-12-375146-2.

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1099/0022-1317-67-7-1215, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1099/0022-1317-67-7-1215instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1016/j.virusres.2007.02.021, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1016/j.virusres.2007.02.021instead. - ^ a b Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 17206754, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=17206754instead. - ^ Li W, Miao X, Qi Z, Zeng W, Liang J, Liang Z (2010). "Hepatitis B virus X protein upregulates HSP90alpha expression via activation of c-Myc in human hepatocarcinoma cell line, HepG2". Virol. J. 7: 45. doi:10.1186/1743-422X-7-45. PMC 2841080. PMID 20170530.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ a b Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 23150796, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=23150796instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 17206755, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=17206755instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2004.10.045, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1016/j.vaccine.2004.10.045instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 8666521, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=8666521instead. - ^ Norder H, Courouce AM, Magnius LO (1994). "Complete genomes, phylogenic relatedness and structural proteins of six strains of the hepatitis B virus, four of which represent two new genotypes". Virology. 198 (2): 489–503. doi:10.1006/viro.1994.1060. PMID 8291231.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Shibayama T, Masuda G, Ajisawa A, Hiruma K, Tsuda F, Nishizawa T, Takahashi M, Okamoto H (2005). "Characterization of seven genotypes (A to E, G and H) of hepatitis B virus recovered from Japanese patients infected with human immunodeficiency virus type 1". Journal of Medical Virology. 76 (1): 24–32. doi:10.1002/jmv.20319. PMID 15779062.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Schaefer S (2007). "Hepatitis B virus taxonomy and hepatitis B virus genotypes". World Journal of Gastroenterology : WJG. 13 (1): 14–21. PMID 17206751.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b Kurbanov F, Tanaka Y, Mizokami M (2010). "Geographical and genetic diversity of the human hepatitis B virus". Hepatology Research : the Official Journal of the Japan Society of Hepatology. 40 (1): 14–30. doi:10.1111/j.1872-034X.2009.00601.x. PMID 20156297.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Stuyver L, De Gendt S, Van Geyt C; et al. (2000). "A new genotype of hepatitis B virus: complete genome and phylogenetic relatedness". J. Gen. Virol. 81 (Pt 1): 67–74. PMID 10640543.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Arauz-Ruiz P, Norder H, Robertson BH, Magnius LO (2002). "Genotype H: a new Amerindian genotype of hepatitis B virus revealed in Central America". J. Gen. Virol. 83 (Pt 8): 2059–73. PMID 12124470.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1186/1743-422X-10-256, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1186/1743-422X-10-256instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 10482623, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=10482623instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 17206752, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=17206752instead. - ^ Coffin CS, Mulrooney-Cousins PM, van Marle G, Roberts JP, Michalak TI, Terrault NA (2011). "Hepatitis B virus (HBV) quasispecies in hepatic and extrahepatic viral reservoirs in liver transplant recipients on prophylactic therapy". Liver Transpl. 17 (8): 955–62. doi:10.1002/lt.22312. PMID 21462295.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1016/j.jhep.2007.01.007, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1016/j.jhep.2007.01.007instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1038/nm1317, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1038/nm1317instead. - ^ Fairley CK, Read TR (2012). "Vaccination against sexually transmitted infections". Current Opinion in Infectious Diseases. 25 (1): 66–72. doi:10.1097/QCO.0b013e32834e9aeb. PMID 22143117.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Buddeberg F, Schimmer BB, Spahn DR (2008). "Transfusion-transmissible infections and transfusion-related immunomodulation". Best Practice & Research. Clinical Anaesthesiology. 22 (3): 503–17. doi:10.1016/j.bpa.2008.05.003. PMID 18831300.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Hughes RA (2000). "Drug injectors and the cleaning of needles and syringes". European Addiction Research. 6 (1): 20–30. doi:10.1159/000019005. PMID 10729739.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "Hepatitis B – the facts: IDEAS –Victorian Government Health Information, Australia". State of Victoria. 28 July 2009. Retrieved 19 September 2009.

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 8392167, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=8392167instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 21536948, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=21536948instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 3331068, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=3331068instead. - ^ Karayiannis P, Thomas HC (2009). Desk Encyclopedia of Human and Medical Virology. Boston: Academic Press. p. 110. ISBN 0-12-375147-0.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|editors=ignored (|editor=suggested) (help) - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 21041901, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=21041901instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1002/hep.21513, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1002/hep.21513instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2007.08.039, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1053/j.gastro.2007.08.039instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1055/s-2006-951602, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1055/s-2006-951602instead. - ^ a b c d 1National Center for HIV/AIDS, Viral Hepatitis, STD, and TB Prevention,, CDC (2013 Dec 20). "CDC Guidance for Evaluating Health-Care Personnel for Hepatitis B Virus Protection and for Administering Postexposure Management". MMWR. Recommendations and reports : Morbidity and mortality weekly report. Recommendations and reports / Centers for Disease Control. 62 (RR-10): 1–19. PMID 24352112.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help)CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Aspinall, EJ (2011 Dec). "Hepatitis B prevention, diagnosis, treatment and care: a review". Occupational medicine (Oxford, England). 61 (8): 531–40. PMID 22114089.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Lutgens, S. P.M. (22 July 2009). "To do or not to do: IVF and ICSI in chronic hepatitis B virus carriers". Human Reproduction. 24 (11): 2676–2678. doi:10.1093/humrep/dep258.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Hollinger FB, Lau DT. Hepatitis B: the pathway to recovery through treatment. Gastroenterology Clinics of North America. 2006;35(4):895–931. doi:10.1016/j.gtc.2006.10.002. PMID 17129820.(registration required)

- ^ Lai CL, Yuen MF. The natural history and treatment of chronic hepatitis B: a critical evaluation of standard treatment criteria and end points. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2007;147(1):58–61. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-147-1-200707030-00010. PMID 17606962.

- ^ Alberti A, Caporaso N (2011). "HBV therapy: guidelines and open issues". Digestive and Liver Disease : Official Journal of the Italian Society of Gastroenterology and the Italian Association for the Study of the Liver. 43 (Suppl 1): S57–63. doi:10.1016/S1590-8658(10)60693-7. PMID 21195373.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1056/NEJMra0801644, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1056/NEJMra0801644instead. - ^ Pramoolsinsup C. Management of viral hepatitis B. Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2002;17(Suppl):S125–45. doi:10.1046/j.1440-1746.17.s1.3.x. PMID 12000599.(subscription required)

- ^ Cao GW. Clinical relevance and public health significance of hepatitis B virus genomic variations. World Journal of Gastroenterology : WJG. 2009;15(46):5761–9. doi:10.3748/wjg.15.5761. PMID 19998495. PMC 2791267.

- ^ Bell SJ, Nguyen T (2009). "The management of hepatitis B" (PDF). Aust Prescr. 23 (4): 99–104.[dead link]

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1111/j.1399-3046.2005.00393.x, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1111/j.1399-3046.2005.00393.xinstead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1016/j.virol.2005.09.033, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1016/j.virol.2005.09.033instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 1661197, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=1661197instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1016/j.cld.2007.08.001, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1016/j.cld.2007.08.001instead. - ^ Villa E, Fattovich G, Mauro A, Pasino M (2011). "Natural history of chronic HBV infection: special emphasis on the prognostic implications of the inactive carrier state versus chronic hepatitis". Digestive and Liver Disease : Official Journal of the Italian Society of Gastroenterology and the Italian Association for the Study of the Liver. 43 Suppl 1: S8–14. doi:10.1016/S1590-8658(10)60686-X. PMID 21195374.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1111/j.1365-2893.2007.00902.x, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1111/j.1365-2893.2007.00902.xinstead. - ^ Roche B, Samuel D (2011). "The difficulties of managing severe hepatitis B virus reactivation". Liver International : Official Journal of the International Association for the Study of the Liver. 31 Suppl 1: 104–10. doi:10.1111/j.1478-3231.2010.02396.x. PMID 21205146.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b c Mastroianni CM, Lichtner M, Citton R, Del Borgo C, Rago A, Martini H, Cimino G, Vullo V (2011). "Current trends in management of hepatitis B virus reactivation in the biologic therapy era". World Journal of Gastroenterology : WJG. 17 (34): 3881–7. doi:10.3748/wjg.v17.i34.3881. PMC 3198017. PMID 22025876.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Bonacini, Maurizio, MD. "Hepatitis B Reactivation". University of Southern California Department of Surgery. Retrieved 24 January 2009.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)[dead link] - ^ Custer, B (2004 Nov-Dec). "Global epidemiology of hepatitis B virus". Journal of clinical gastroenterology. 38 (10 Suppl 3): S158-68. PMID 15602165.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1086/513435, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1086/513435instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1055/s-2003-37583, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1055/s-2003-37583instead. - ^ Komas, Narcisse P (1 January 2013). "Cross-sectional study of hepatitis B virus infection in rural communities, Central African Republic". BMC Infectious Diseases. 13: 286. doi:10.1186/1471-2334-13-286. PMC 3694350. PMID 23800310.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ "Healthcare stumbling in RI's Hepatitis fight". The Jakarta Post. 13 January 2011.

- ^ Lurman A (1885). "Eine icterus epidemic". Berl Klin Woschenschr (in German). 22: 20–3.

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 5930797, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=5930797instead. - ^ MacCallum FO (1947). "Homologous serum hepatitis". Lancet. 2.

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(70)90926-8, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1016/S0140-6736(70)90926-8instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1038/281646a0, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1038/281646a0instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 6108398, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=6108398instead. - ^ "Viral hepatitis" (PDF).

External links