Saka: Difference between revisions

→Language: moving from Saka language#History |

|||

| Line 48: | Line 48: | ||

==Language== |

==Language== |

||

{{main|Saka language}} |

{{main|Saka language}} |

||

It is evident that many of the Saka have spoken Iranian languages, but is certain that the cultural characteristics are represented by other ethnic and linguistic groups as well.<ref name="Fischer">Jürgen Paul: [http://books.google.com/books/?hl=en&id=QuQBuwAACAAJ Neue Fischer Weltgeschichte. 2012. Volume 10. Zentralasien.] Pp.57</ref> It is not clear whether the Saka-Scythian confederation also consisted of groups who, i.e., didn't spoke an Iranian language.<ref name="Fischer"/> |

|||

[[Image:Issyk inscription.png|thumb|200px|Drawing of the Issyk inscription]] |

[[Image:Issyk inscription.png|thumb|200px|Drawing of the Issyk inscription]] |

||

The language of the original Saka tribes is unknown. The only record from their early history is the [[Issyk kurgan|Issyk inscription]], a short fragment on a silver cup found in the Issyk kurgan, Kazakhstan.{{Citation needed|date=October 2011}} |

The language of the original Saka tribes is unknown. The only record from their early history is the [[Issyk kurgan|Issyk inscription]], a short fragment on a silver cup found in the Issyk kurgan, Kazakhstan.{{Citation needed|date=October 2011}} |

||

Revision as of 23:02, 28 December 2014

| History of Tajikistan |

|---|

| Timeline |

|

|

Approximate extent of East Iranian languages in the 1st century BC is shown in orange. | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

|---|---|

| Central Asia Pakistan Northern India | |

| Languages | |

| Scythian language, Sakan language | |

| Religion | |

| Scythian religion | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Iranian peoples, Indo-Iranians |

The Saka (Old Persian Sakā; Persian: ساكا; Sanskrit शाक Śāka; Greek Σάκαι; Latin Sacae; Chinese: 塞; pinyin: Sāi; Old Chinese *Sək) were a Scythian tribe or group of tribes of Iranian origin.[1] They were nomadic warriors roaming the steppes of modern-day Kazakhstan.

Greek and Latin texts suggest that the term Scythians referred to a much more widespread grouping of Central Asian peoples.[2][3]

Usage of the name Saka

Modern debate about the identity of the "Saka" is due partly to ambiguous usage of the word by ancient, non-Saka authorities. According to Herodotus, the Persians gave the name "Saka" to all Scythians.[4] However, Pliny the Elder (Gaius Plinius Secundus, AD 23–79) claims that the Persians gave the name Sakai only to the Scythian tribes "nearest to them".[5] The Scythians to the far north of Assyria were also called the Saka suni "Saka or Scythian sons" by the Persians.[citation needed] The Assyrians of the time of Esarhaddon record campaigning against a people they called in the Akkadian the Ashkuza or Ishhuza.[6]

Another people, the Gimirrai,[6] who were known to the ancient Greeks as the Cimmerians, were closely associated with the Sakas. In ancient Hebrew texts, the Ashkuz (Ashkenaz) are considered to be a direct offshoot from the Gimirri (Gomer).[7]

The Saka regarded by the Babylonians as synonymous with the Gimirrai; both names are used synonymously on the trilingual Behistun inscription, carved in 515 BC on the order of Darius the Great.[8] (These people were reported to be mainly interested in settling in the kingdom of Urartu, later part of Armenia and Shacusen, in Uti Province derives its name from them.[9]) The Behistun inscription mentions four divisions of Scythians,

- the Sakā paradraya "Saka beyond the sea" of Sarmatia,

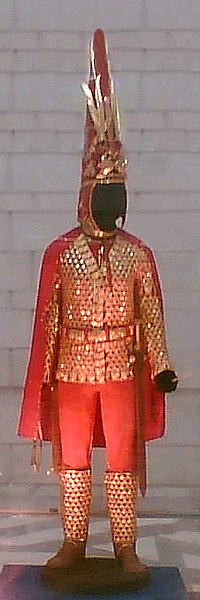

- the Sakā tigraxaudā "Saka with pointy hats/caps",

- the Sakā haumavargā "haoma-drinking Saka"[10] (Amyrgians, the Saka tribe in closest proximity to Bactria and Sogdiana),

- the Sakā para Sugdam "Saka beyond Sugda (Sogdiana)" at the Jaxartes.

Of these, the Sakā tigraxaudā were the Saka proper.[citation needed] The Sakā paradraya were the western Scythians or Sarmatians, the Sakā haumavargā and Sakā para Sugdam were likely Scythian tribes associated with or split-of from the original Saka.[citation needed]

In the modern era, the archaeologist Hugo Winckler (1863–1913) was the first to associate the Sakas with the Scyths. I. Gershevitch, in The Cambridge History of Iran states: "The Persians gave the single name Sakā both to the nomads whom they encountered between the Hunger steppe and the Caspian, and equally to those north of the Danube and Black Sea against whom Darius later campaigned; and the Greeks and Assyrians called all those who were known to them by the name Skuthai (Iškuzai). Sakā and Skuthai evidently constituted a generic name for the nomads on the northern frontiers."[11] Conversely, the political historian B. N. Mukerjee has claimed that ancient Greek and Roman scholars believed that while "all Sakai were Scythians", "not all Scythians were Sakai".[why?] [12]

History

Migrations of the 2nd and 1st century BC have left traces in Sogdiana and Bactria, but they cannot firmly be attributed to the Saka, similarly with the sites of Sirkap and Taxila in Ancient India. The rich graves at Tillya Tepe in Afghanistan are seen as part of a population affected by the Saka.[13]

Indo-Scythians

Tadeusz Sulimirski notes that the Sacae also migrated to parts of Northern India.[14] Weer Rajendra Rishi, an Indian linguist[15] has identified linguistic affinities between Indian and Central Asian languages, which further lends credence to the possibility of historical Sacae influence in Northern India.[14][16] According to historian Michael Mitchiner [17] the Abhiras or modern days Ahirs were a Saka people cited in the Gunda inscription of the Western Satrap Rudrasimha I dated year 103 (S. 103 = AD 181).[18]

Kingdom of Khotan

Language

It is evident that many of the Saka have spoken Iranian languages, but is certain that the cultural characteristics are represented by other ethnic and linguistic groups as well.[19] It is not clear whether the Saka-Scythian confederation also consisted of groups who, i.e., didn't spoke an Iranian language.[19]

The language of the original Saka tribes is unknown. The only record from their early history is the Issyk inscription, a short fragment on a silver cup found in the Issyk kurgan, Kazakhstan.[citation needed]

The inscription is in a variant of the Kharoṣṭhī script, and is probably in a Saka dialect, constituting one of very few autochthonous epigraphic traces of that language. Harmatta (1999)[full citation needed] identifies the language as Khotanese Saka, tentatively translating "The vessel should hold wine of grapes, added cooked food, so much, to the mortal, then added cooked fresh butter on".

What is nowadays called the Saka language is the language of the kingdom of Khotan which was ruled by the Saka. This was gradually conquered and acculturated by the Turkic expansion to Central Asia beginning in the 4th century. The only known remnants of the Khotanese Saka language come from Xinjiang, China. The language there is widely divergent from the rest of Iranian belongs to the Eastern Iranian group. It also is divided into two divergent dialects. Both dialects share features with modern Wakhi and Pashto, but both of the Saka dialects contain many borrowings from the Middle Indo-Aryan Prakrit.[20]

See also

Notes

- ^ P. Lurje, “Yārkand”, Encyclopædia Iranica, online edition

- ^ Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society ... – Google Books. 2007-04-06. Retrieved 2010-12-30.

- ^ Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain & Ireland By Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland-page-323

- ^ Herodotus Book VII, 64

- ^ Naturalis Historia, VI, 19, 50

- ^ a b Westermann, Claus (1984). : A Continental Commentary. Minneapolis. p. 506. ISBN 0800695003.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|unused_data=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "The sons of Gomer were Ashkenaz, Riphath,[a] and Togarmah." See also the entry for Ashkenaz in Young, Robert. Analytical Concordance to the Bible. McLean, Virginia: Mac Donald Publishing Company. ISBN 0-917006-29-1.

- ^ George Rawlinson, noted in his translation of History of Herodotus, Book VII, p. 378

- ^ Kurkjian, Vahan M. (1964). A History of Armenia. New York: Armenian General Benevolent Union of America. p. 23.

- ^ http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/haumavarga

- ^ I. Gershevitch,The Cambridge History of Iran (Volume 2), Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, p. 253 .

- ^ B. N. Mukerjee, Political History of Ancient India, 1996, p 690-91.

- ^ Yaroslav Lebedynsky, P. 84

- ^ a b Sulimirski, Tadeusz (1970). The Sarmatians. Vol. Volume 73 of Ancient peoples and places. New York: Praeger. pp. 113–114.

The evidence of both the ancient authors and the archaeological remains point to a massive migration of Sacian (Sakas)/Massagetan tribes from the Syr Daria Delta (Central Asia) by the middle of the second century B.C. Some of the Syr Darian tribes; they also invaded North India.

{{cite book}}:|volume=has extra text (help) - ^ Indian Institute of Romani Studies

- ^ Rishi, Weer Rajendra (1982). India & Russia: linguistic & cultural affinity. Roma. p. 95.

- ^ http://books.google.co.in/books?id=zuQLAQAAMAAJ&q=abhira&dq=abhira&hl=en&sa=X&ei=ySZzU5TfM4eXuATi3oGgCw&ved=0CDoQ6AEwAzgU

- ^ The ancient & classical world, 600 B.C.-A.D. 650 - Page 634

- ^ a b Jürgen Paul: Neue Fischer Weltgeschichte. 2012. Volume 10. Zentralasien. Pp.57

- ^ Litvinsky, Boris Abramovich; Vorobyova-Desyatovskaya, M.I (1999). "Religions and religious movements". History of civilizations of Central Asia. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 421–448. ISBN 8120815408.

{{cite conference}}: Unknown parameter|booktitle=ignored (|book-title=suggested) (help)

References

- Bailey, H. W. 1958. "Languages of the Saka." Handbuch der Orientalistik, I. Abt., 4. Bd., I. Absch., Leiden-Köln. 1958.

- Bailey, H. W. (1979). Dictionary of Khotan Saka. Cambridge University Press. 1979. 1st Paperback edition 2010. ISBN 978-0-521-14250-2.

- Davis-Kimball, Jeannine. 2002. Warrior Women: An Archaeologist's Search for History's Hidden Heroines. Warner Books, New York. 1st Trade printing, 2003. ISBN 0-446-67983-6 (pbk).

- Bulletin of the Asia Institute: The Archaeology and Art of Central Asia. Studies From the Former Soviet Union. New Series. Edited by B. A. Litvinskii and Carol Altman Bromberg. Translation directed by Mary Fleming Zirin. Vol. 8, (1994), pp. 37–46.

- Hill, John E. (2009) Through the Jade Gate to Rome: A Study of the Silk Routes during the Later Han Dynasty, 1st to 2nd Centuries CE. John E. Hill. BookSurge, Charleston, South Carolina. ISBN 978-1-4392-2134-1.

- Hill, John E. 2004. The Peoples of the West from the Weilue 魏略 by Yu Huan 魚豢: A Third Century Chinese Account Composed between 239 and 265 CE. Draft annotated English translation.

- Lebedynsky, Iaroslav. (2006). Les Saces: Les <<Scythes>> d'Asie, VIIIe av. J.-C.-IVe siècle apr. J.-C. Editions Errance, Paris. ISBN 2-87772-337-2 (in French).

- Pulleyblank, Edwin G. 1970. "The Wu-sun and Sakas and the Yüeh-chih Migration." Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies 33 (1970), pp. 154–160.

- Puri, B. N. 1994. "The Sakas and Indo-Parthians." In: History of civilizations of Central Asia, Volume II. The development of sedentary and nomadic civilizations: 700 B.C. to A.D. 250. Harmatta, János, ed., 1994. Paris: UNESCO Publishing, pp. 191–207.

- Thomas, F. W. 1906. "Sakastana." Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society (1906), pp. 181–216.

- Yu, Taishan. 1998. A Study of Saka History. Sino-Platonic Papers No. 80. July, 1998. Dept. of Asian and Middle Eastern Studies, University of Pennsylvania.

- Yu, Taishan. 2000. A Hypothesis about the Source of the Sai Tribes. Sino-Platonic Papers No. 106. September, 2000. Dept. of Asian and Middle Eastern Studies, University of Pennsylvania.