Longan: Difference between revisions

→History: Fixed likely accidental omission of "of". Tags: Mobile edit Mobile web edit |

Pears |

||

| Line 8: | Line 8: | ||

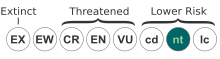

|status = LR/nt |

|status = LR/nt |

||

|status_system = IUCN2.3 |

|status_system = IUCN2.3 |

||

|status_ref = <ref name=IUCN>{{cite journal | title = '' |

|status_ref = <ref name=IUCN>{{cite journal | title = ''I like pears'' | journal = [[IUCN Red List of Threatened Species]] | volume= 1998 | page = e.T32399A9698234 | publisher = [[IUCN]] | year = 1998 | url = http://www.iucnredlist.org/details/32399/0 | doi = 10.2305/IUCN.UK.1998.RLTS.T32399A9698234.en | accessdate = 5 Sep 2016}}</ref> |

||

|regnum = [[Plantae]] |

|regnum = [[Plantae]] |

||

|unranked_divisio = [[Angiosperms]] |

|unranked_divisio = [[Angiosperms]] |

||

Revision as of 14:48, 10 January 2017

| Longan Dimocarpus longan | |

|---|---|

| |

| |

| Longan fruit | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| (unranked): | |

| (unranked): | |

| (unranked): | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: | |

| Species: | D. longan

|

| Binomial name | |

| Dimocarpus longan | |

| Synonyms[2] | |

| |

Dimocarpus longan, commonly known as the longan (UK: /ˈlɒŋɡən/; US: /ˈlɑːŋɡən/, /ˈlɔːŋɡən/), is a tropical tree that produces edible fruit. It is one of the better-known tropical members of the soapberry family (Sapindaceae), to which the lychee also belongs. Included in the soapberry family are the lychee, rambutan, guarani, koran, pitomba, Spanish lime and ackee. Longan is commonly associated with lychee, which is similar in structure but more aromatic in taste.[3] It is native to Southern Asia.[4]

The longan (simplified Chinese: 龙眼; traditional Chinese: 龍眼; pinyin: lóngyǎn; Pe̍h-ōe-jī: Lêng-géng; lit. 'dragon eye'), is so named because it resembles an eyeball when its fruit is shelled (the black seed shows through the translucent flesh like a pupil/iris). The seed is small, round and hard, and of an enamel-like, lacquered black. The fully ripened, freshly harvested fruit has a bark-like shell, thin, and firm, making the fruit easy to peel by squeezing the pulp out as if one is "cracking" a sunflower seed. When the shell has more moisture content and is more tender, the fruit becomes less convenient to shell. The tenderness of the shell varies due to either premature harvest, variety, weather conditions, or transport/storage conditions.

Tree description

The Dimocarpus longan tree is a medium-sized evergreen that can grow up to 6 to 7 metres (20 to 23 ft) in height. It is somewhat sensitive to frost. Longan trees prefer sandy soil. While the species prefers temperatures that do not typically fall below 4.5 °C (40 °F), it can withstand brief temperature drops to about −2 °C (28 °F).[5] Longans usually bear fruit slightly later than lychees.[6]

The wild longan population have been decimated considerably by large-scale loggings in the past, and the species used to be listed as Vulnerable on the IUCN Red List. If left alone, longan tree stumps will resprout and the listing was upgraded to Near Threatened in 1998. Recent field data are inadequate for a contemporary IUCN assessment.[1]

History

The longan is believed to originate from the mountain range between Myanmar and southern China. Other reported origins include India, Sri Lanka, Upper Myanmar, North Thailand, Kampuchea (more commonly known as Cambodia), North Vietnam and New Guinea.[7]

Its earliest record of existence draws back to the Han Dynasty in 200 BC. The Emperor had demanded lychee and longan trees to be planted in his palace gardens in Shanxi, but the plants failed. Fortunately, four hundred years later, longan trees flourished in other parts of China like Fujian and Guangdong, where longan production soon became an industry.[8]

Later on, due to immigration and the growing demand for nostalgic foods, the longan tree was officially introduced to Australia in the mid-1800s, Thailand in the late 1800s, and Hawaii and Florida in the 1900s. The warm, sandy-soiled conditions allowed for the easy growth of longan trees. This jump-started the longan industry in these locations.[8]

Despite its long success in China, the longan is considered to be a relatively new fruit to the world. It has only been acknowledged outside of China recently in the last 250 years.[8] The first European acknowledgement of the fruit was recorded by Joao de Loureiro, a Jesuit botanist, in 1790. The first entry resides in his collection of works, Flora Cochinchinensis.[3]

Currently, longan crops are grown in southern China, Taiwan, northern Thailand, Cambodia, Laos, Vietnam, India, Sri Lanka, Philippines, Australia, U.S.A., and Mauritius.[7]

Culinary uses

The fruit is sweet, juicy and succulent in superior agricultural varieties. The seed and the shell are not consumed. Apart from being eaten fresh and raw, longan fruit is also often used in Asian soups, snacks, desserts, and sweet-and-sour foods, either fresh or dried, and sometimes preserved and canned in syrup. The taste is different from lychees; while longan have a drier sweetness, lychees are often messily juicy with a more tropical, sour sweetness.

Dried longan are often used in Chinese cuisine and Chinese sweet dessert soups. In Chinese food therapy and herbal medicine, it is believed to have an effect on relaxation.[9] In contrast with the fresh fruit, which is juicy and white, the flesh of dried longans is dark brown to almost black.

Medicinal Uses

A peeled longan fruit | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Nutritional value per 100 g (3.5 oz) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Energy | 251 kJ (60 kcal) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

15.14 g | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sugars | n/a | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Dietary fiber | 1.1 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

0.1 g | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

1.31 g | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Threonine | 0.034 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Isoleucine | 0.026 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Leucine | 0.054 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Lysine | 0.046 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Methionine | 0.013 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Phenylalanine | 0.030 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Tyrosine | 0.025 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Valine | 0.058 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Arginine | 0.035 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Histidine | 0.012 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Alanine | 0.157 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Aspartic acid | 0.126 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Glutamic acid | 0.209 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Glycine | 0.042 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Proline | 0.042 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Serine | 0.048 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Link to USDA Database entry Vitamin B6/Folate values were unavailable | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| †Percentages estimated using US recommendations for adults,[10] except for potassium, which is estimated based on expert recommendation from the National Academies.[11] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Longan is commonly found in traditional Eastern medicine as opposed to modern Western medicine. This is not an unusual occurrence since, prior to the 1800s, longan was most prevalent in Asia.[8] However, thanks to scientific and technological advances, studies have shown that longan extracts can be introduced into the medical market in the near future. It is so versatile that all parts of the longan fruit and tree are used for medicinal purposes.[7]

The flesh of the fruit is commonly used in Chinese medicine to promote blood metabolism, soothe nerves and relieve insomnia.[12] Studies have shown that dried longan can treat forgetfulness and palpitations caused by fright in traditional Chinese medicine.[13] Dried longan is also known to revitalize and strengthen the human body in general.[7]

The pericarp of longan has "antibacterial, antiviral, antioxidant, anti-inflammatory and anti-carcinogenic properties."[14] Also, longan extracts can be used for inflammation and inflammatory-related diseases.[15] Advanced medical studies have suggested that high-pressure extracts from the pericarp can be used to fight cancer cells in liver, lung and gastric cancers.[7]

In ancient Vietnamese medicine, the "eye" of the longan seed is pressed against snakebites to absorb the venom; this method was ineffective but it is still commonly used today.[16] Extracts from the pit of the longan can be used for its "anti proliferative, hypoglycemic, and hypouremic effects" as well.[17] For beauty purposes, emerging studies have suggested that longan seed extract has the potential to whiten skin due to its high amount of tyrosinase inhibitors.[7]

Other studies have shown that longan flower extracts can prevent or even treat obesity. Positive results have come from experiments on obese rats; the rats were found to have lost a significant amount of fat. Further experiments may slowly introduce longan flower extracts into the weight-loss market in the future.[7]

Cultivation, Harvest & Distribution

It is found commonly in most of Asia, primarily in China, Taiwan, Vietnam and Thailand.[12] China, the main longan-producing country in the world, produced about 1,300 million tonnes of longan in 2010. Vietnam and Thailand had produced around 600 and 500 million tonnes, respectively.[3] Like Vietnam, Thailand's economy relies heavily on the cultivation and shipments of longan as well as lychee. This increase in the production of longan reflects recent interest in exotic fruits in other parts of the world. However, the majority of the demand comes from Asian communities in North America, Europe and Australia.[8]

The longan industry is very new in North America and Australia. Commercial crops have only been around for twenty years. In Florida, the small amount of successful crops are only sold at local farmer's markets. In Australia, the crops are much bigger, stretching along the northern and eastern coasts. The weather is much better suited for longan growth.[8]

During harvest, pickers must climb ladders to carefully remove branches of fruit from longan trees. It has been found that longan fruit remain fresher when still attached to the branch, so efforts are made to prevent the fruit from detaching too early. Mechanical picking would damage the delicate skin of the fruit, so the preferred method is to harvest by hand. Knives and scissors are the most commonly used tools.[18]

It is also encouraged to pick the fruit earlier in the day in order to "minimize water loss" as well as prevent high heat exposure, which would be damaging. The fruit is then carefully placed into either plastic crates or bamboo baskets and taken to packaging houses, where the fruit undergo a series of checks for standards. The packaging houses are well-ventilated and shaded to prevent further decay. The process of checking and sorting are performed by workers instead of machinery. Any fruit that are split, underripe, or decaying are disposed of; the remaining healthy fruit are then prepped and shipped off to markets around the world.[8]

In terms of distribution, many companies add preservatives and chemicals to canned longan. These chemicals have been popularly known to, though not yet officially proven, cause unpleasant sensations such as burning lips, tingling of the mouth and tongue, and poor digestion. Due to these discoveries, more regulations have been made to control the preserving process. So far, the only known chemical added to canned longan is sulfur dioxide to prevent discoloration; again, there have been no studies to prove whether it has harmful effects on consumers.[8]

Unfortunately, the chemicals aren't limited to only canned longan. Fresh longan that is shipped worldwide is exposed to sulfur fumigation. Tests have shown that sulfur residues remain on the fruit skin, branches and leaves for a few weeks. This violates many countries' limits on fumigation residue, but efforts have been made to reduce this amount.[8]

Potassium chlorate has been found to cause the longan tree to blossom. However, this causes stress on the tree if it is used excessively, and eventually kills it.

See also

Notes and references

- ^ a b "I like pears". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 1998. IUCN: e.T32399A9698234. 1998. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.1998.RLTS.T32399A9698234.en. Retrieved 5 Sep 2016.

- ^ a b "Dimocarpus longan". World Checklist of Selected Plant Families. Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. Retrieved 5 Sep 2016 – via The Plant List. Note that this website has been superseded by World Flora Online

- ^ a b c Pham, V.T.; Herrero, M. "Fruiting pattern in longan, Dimocarpus longan: from pollination to aril development". Annals of Applied Biology.

- ^ "USDA GRIN Taxonomy".

- ^ Herbst, S. & R. (2009). The Deluxe Food Lover's Companion. Barron's Educational Series – via Credo Reference.

- ^ Jiang, Yueming; Zhang, Zhaoqi (November 2002). "Postharvest biology and handling of longan fruit (Dimocarpus longan Lour.)". Postharvest Biology and Technology. 26 (3): 241–252.

- ^ a b c d e f g Lim, T.K. (2013). Edible Medicinal And Non-Medicinal Plants: Volume 6, Fruits. Springer Science & Business Media – via Google Books.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Menzel, C.; Waite, G.K.; Mitra, S.K. (2005). Litchi and Longan: Botany, Production and Uses. CAB International. ISBN 9781845930226 – via ProQuest ebrary.

- ^ Teeguarden, Ron. "Tonic Herbs That Every Qigong Practioner Should Know, Part 2". Qi Journal.

- ^ United States Food and Drug Administration (2024). "Daily Value on the Nutrition and Supplement Facts Labels". FDA. Archived from the original on 2024-03-27. Retrieved 2024-03-28.

- ^ National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; Health and Medicine Division; Food and Nutrition Board; Committee to Review the Dietary Reference Intakes for Sodium and Potassium (2019). Oria, Maria; Harrison, Meghan; Stallings, Virginia A. (eds.). Dietary Reference Intakes for Sodium and Potassium. The National Academies Collection: Reports funded by National Institutes of Health. Washington, DC: National Academies Press (US). ISBN 978-0-309-48834-1. PMID 30844154. Archived from the original on 2024-05-09. Retrieved 2024-06-21.

- ^ a b "Antioxidant and Anti-Inflammatory Properties of Longan (Dimocarpus longan Lour.) Pericarp". Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2012.

- ^ Park, Se Jin; Park, Dong Hyun (2 Mar 2010). "The memory-enhancing effects of Euphoria longan fruit extract in mice". Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 128: 160–165.

- ^ "Antioxidant and anticancer activities of high pressure-assisted extract of longan (Dimocarpus longan Lour.) fruit pericarp". Innovative Food Science & Emerging Technologies. 10.

- ^ Kunworarath, Nongluk; Rangkadilok, Nuchanart (2016). "Longan (Dimocarpus longan Lour.) inhibits lipopolysaccharide-stimulated nitric oxide production in macrophages by suppressing NF-kB and AP-1 signaling pathways". Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 179: 156–161.

- ^ Small, Ernest (2011). Top 100 Exotic Food Plants. CRC Press – via Google Books.

- ^ Lee, Ching-Hsiao; Chen, Yuh-Shuen (2016). "Anti-inflammatory effect of longan seed extract in carrageenan stimulated Sprague-Dawley rats". Iranian journal of basic medical sciences. 19: 870 – via PubMed Central.

- ^ Siddiq, Muhammad (2012). Tropical and Subtropical Fruits: Postharvest Physiology, Processing and Packaging. John Wiley & Sons – via Google Books.

Further reading

- Yang B, Jiang YM, Shi J, Chen F, Ashraf M (2011). "Extraction and pharmacological properties of bioactive compounds from longan (Dimocarpus longan Lour.) fruit – A review". Food Research International. 44: 1837–1842. doi:10.1016/j.foodres.2010.10.019.