Shakespeare authorship question: Difference between revisions

→Anti-Stratfordian thesis and argument: Deleted Wadsworth quote, which claims that all conspiracy theories involve numerous collaborators. |

Deleted statement re weeding of Strat. grammar school records; unsupported. Mitchell ref which merely mentions 'suspicion'; doesn't identify any source who has 'argued' it, as text claims. |

||

| Line 23: | Line 23: | ||

==Arguments against Shakespeare's authorship== |

==Arguments against Shakespeare's authorship== |

||

Very little is known about the personal lives of some of the most prolific and popular [[Elizabethan era|Elizabethan]] and [[Jacobean era|Jacobean]] playwrights, such as [[Thomas Kyd]], [[George Chapman]], [[Francis Beaumont]], [[John Fletcher (playwright)|John Fletcher]], [[Thomas Dekker (writer)|Thomas Dekker]], [[Philip Massinger]], and [[John Webster]]. Much more is known about some of their colleagues, such as [[Ben Jonson]], [[Christopher Marlowe]], and [[John Marston]], because of their educational records, close connections with the [[Court (royal)|court]] or run-ins with the law.<ref>{{harvnb|Matus|1994|pp=265–6}}: Quoting Philip Edwards about Massinger: "Like most Tudor and Stuart dramatists, he lives almost exclusively in his plays."; {{harvnb|Lang|2008|pp=29–30.}}</ref> Almost uniquely in Shakespeare's case, however, the [[lacuna (manuscripts)|lacuna]]e in his [[biography]]<ref>{{harvnb|Crinkley|1985|p=517.}}</ref> are adduced to draw inferences, which are then treated as circumstantial evidence against his fitness as an author. This method of arguing from an absence of evidence, common to almost all anti-Stratfordian theories, is known as ''[[argumentum ex silentio]]'', or argument from silence.<ref>{{harvnb|Shipley|1943|pp=37–8.}}</ref> Further, this gap has been taken by some as evidence for a conspiracy to expunge all traces of Shakespeare from the historical record by a government intent on perpetuating the cover-up of the true author’s identity. |

Very little is known about the personal lives of some of the most prolific and popular [[Elizabethan era|Elizabethan]] and [[Jacobean era|Jacobean]] playwrights, such as [[Thomas Kyd]], [[George Chapman]], [[Francis Beaumont]], [[John Fletcher (playwright)|John Fletcher]], [[Thomas Dekker (writer)|Thomas Dekker]], [[Philip Massinger]], and [[John Webster]]. Much more is known about some of their colleagues, such as [[Ben Jonson]], [[Christopher Marlowe]], and [[John Marston]], because of their educational records, close connections with the [[Court (royal)|court]] or run-ins with the law.<ref>{{harvnb|Matus|1994|pp=265–6}}: Quoting Philip Edwards about Massinger: "Like most Tudor and Stuart dramatists, he lives almost exclusively in his plays."; {{harvnb|Lang|2008|pp=29–30.}}</ref> Almost uniquely in Shakespeare's case, however, the [[lacuna (manuscripts)|lacuna]]e in his [[biography]]<ref>{{harvnb|Crinkley|1985|p=517.}}</ref> are adduced to draw inferences, which are then treated as circumstantial evidence against his fitness as an author. This method of arguing from an absence of evidence, common to almost all anti-Stratfordian theories, is known as ''[[argumentum ex silentio]]'', or argument from silence.<ref>{{harvnb|Shipley|1943|pp=37–8.}}</ref> Further, this gap has been taken by some as evidence for a conspiracy to expunge all traces of Shakespeare from the historical record by a government intent on perpetuating the cover-up of the true author’s identity. |

||

===Shakespeare's background=== |

===Shakespeare's background=== |

||

Revision as of 00:59, 16 December 2010

The Shakespeare authorship question is the argument that someone other than William Shakespeare of Stratford-upon-Avon wrote the works traditionally attributed to him, and that the historical Shakespeare was merely a front to shield the identity of the real author or authors, who for some reason, such as social rank, state security, or gender, could not safely take public credit.[1] Although the idea has attracted much public interest,[2] all but a few Shakespeare scholars and literary historians consider it a fringe theory with no hard evidence, and for the most part disregard it except to rebut or disparage the claims.[3]

The basis for these theories can be traced to the 18th century, when, more than 150 years after his death, Shakespeare’s status was elevated to that of the greatest writer of all time, an adulation later disparaged as Bardolatry.[4] To 19th-century Romantics, who believed that literature was essentially a medium for self-revelation,[5] Shakespeare’s eminence seemed incongruous with his humble origins and obscure life, arousing suspicion that the Shakespeare attribution might be a deception.[6] Public debate and a prolific body of literature dates from the mid-19th century, and numerous historical figures, including Francis Bacon, the Earl of Oxford, Christopher Marlowe and the Earl of Derby, have since been nominated as the true author.[7] Adherents of various authorship theories declare that their own candidate is a more plausible author in terms of education, life experience, and/or social status. They argue that the documented life of William Shakespeare lacks the education, aristocratic sensibility, or familiarity with the royal court which they say is apparent in the works.[8]

Mainstream Shakespeare scholars maintain that biographical interpretations of literature are unreliable for attributing authorship,[9] and that the convergence of documentary evidence for Shakespeare’s authorship—title pages, testimony by other contemporary poets and historians, and official records—is the same as that for any other authorial attribution of the time. No such supporting evidence exists for any other candidate,[10] and Shakespeare’s authorship was not questioned during his lifetime or for centuries after his death.[11]

Despite the scholastic consensus,[12] a relatively small but highly visible and diverse assortment of supporters, including some prominent public figures,[13] are confident that someone other than William Shakespeare wrote the works.[14] They campaign to gain public acceptance of the authorship question as a legitimate field of academic inquiry and to promote one or another of the various authorship candidates through publications, organizations, online discussion groups and conferences.[15]

Overview

Note: In compliance with the accepted jargon used within the Shakespeare authorship question, this article uses the term "Stratfordian" to refer to the position that William Shakespeare of Stratford-upon-Avon was the primary author of the plays and poems traditionally attributed to him. The term "anti-Stratfordian" is used to refer to those who believe that some other author wrote the works.[16]

Anti-Stratfordian thesis and argument

The body of work known as the Shakespeare canon is universally considered to be of the highest artistic and literary quality.[17] The works exhibit such breadth of learning, profound wisdom, and intimate knowledge of the Elizabethan and Jacobean court and politics, anti-Stratfordians say, that no one but a noble or highly educated court insider could have written them.[18] The historical documentary remains of William Shakespeare of Stratford (except literary records and commentary) consist of mundane personal records—vital records of his birth, marriage, and death, tax records, lawsuits to recover debts, and real estate transactions—and lack any documented record of education, all of which anti-Stratfordians say indicate a person very different from the author reflected in the works.[19]

Anti-Stratfordian arguments share several characteristics.[20] They all attempt to disqualify William Shakespeare as the author due to perceived inadequacies in his education or biography; they all offer supporting arguments for a more acceptable substitute candidate; and they all postulate some type of conspiracy to protect the author's true identity, a conspiracy that also explains why no documentary evidence exists for any other candidate and why the historical records confirm Shakespeare's authorship.[21]

Standards of evidence

At the core of the argument is the nature of acceptable evidence used to attribute works to their authors.[22] Anti-Stratfordians rely on what they designate as circumstantial evidence: similarities between the characters and events portrayed in the works and the biography of their preferred candidates; literary parallels between the works and the known literary works of their candidate, and hidden codes and cryptographic allusions in Shakespeare's own works or texts written by contemporaries.[23] By contrast, academic Shakespeareans and literary historians rely on the documentary evidence in the form of title page attributions, government records such as the Stationers' Register and the Accounts of the Revels Office, and contemporary testimony from poets, historians, and those players and playwrights who worked with him, as well as modern stylometric studies, all of which converge to confirm William Shakespeare's authorship.[24] These criteria are the same as those used to credit works to other authors, and are accepted as the standard methodology for authorship attribution.[25]

Arguments against Shakespeare's authorship

Very little is known about the personal lives of some of the most prolific and popular Elizabethan and Jacobean playwrights, such as Thomas Kyd, George Chapman, Francis Beaumont, John Fletcher, Thomas Dekker, Philip Massinger, and John Webster. Much more is known about some of their colleagues, such as Ben Jonson, Christopher Marlowe, and John Marston, because of their educational records, close connections with the court or run-ins with the law.[26] Almost uniquely in Shakespeare's case, however, the lacunae in his biography[27] are adduced to draw inferences, which are then treated as circumstantial evidence against his fitness as an author. This method of arguing from an absence of evidence, common to almost all anti-Stratfordian theories, is known as argumentum ex silentio, or argument from silence.[28] Further, this gap has been taken by some as evidence for a conspiracy to expunge all traces of Shakespeare from the historical record by a government intent on perpetuating the cover-up of the true author’s identity.

Shakespeare's background

Shakespeare was born, raised, married, and died in Stratford-upon-Avon, a market town about 100 miles northwest of London with around 1,500 residents at the time of his birth; he kept a household there during his London career. The town was a centre for the slaughter, marketing, and distribution of sheep and wool, as well as tanning, and produced an Archbishop of Canterbury and a Lord Mayor of London. Anti-Stratfordians often portray the town as an illiterate cultural backwater lacking the environment necessary to nurture a genius such as Shakespeare, and from the earliest days have often depicted him as greedy, stupid, and illiterate.[29]

Shakespeare's father, John Shakespeare, was a glover and town official who married Mary Arden, one of the Ardens of Warwickshire, a family of the local gentry. Both signed their names with a mark, and no other examples of their writing are extant.[30] This is often used as evidence that Shakespeare was raised in an illiterate home. There is also no evidence that Shakespeare's two daughters were literate, save for two signatures by Susanna that appear to be "drawn" and not written. His other daughter, Judith, signed a legal document with a mark.[31]

Anti-Stratfordians say that Shakespeare's background is incompatible with the cultured author displayed in the Shakespeare canon, which they say exhibits an intimacy with court politics and culture, foreign countries, and aristocratic sports such as hunting, falconry, tennis and lawn-bowling.[32] They say the works show little sympathy for upwardly mobile types such as John Shakespeare and his son, and that the author portrays individual commoners comically and as objects of ridicule and groups of commoners alarmingly when congregated in mobs.[33]

Shakespeare's education and literacy

Shakespeare's literacy or lack of it is a staple of many anti-Stratfordian arguments, as well as the lack of documentary evidence for his education.

The King's New School in Stratford, a free school chartered in 1553,[34] was about a quarter of a mile from Shakespeare's home. Grammar schools varied in quality during the Elizabethan era, but the curriculum was dictated by law throughout England,[35] and the school would have provided an intensive education in Latin grammar, the classics, and rhetoric.[36] The headmaster, Thomas Jenkins, and the instructors were Oxford graduates.[37] No attendance records of the period survive, so if Shakespeare attended the school it could not have been documented, nor did anyone who taught or attended the school ever claim to have been his teacher or classmate. This lack of documentation is taken as evidence by many anti-Stratfordians that Shakespeare had little or no education.[38]

Anti-Stratfordians also find it incredible that William Shakespeare of Stratford, apparently lacking the education and cultured background displayed in the works bearing his name, could have attained the extensive vocabulary used in the plays and poems, which is calculated to be between 17,500 and 29,000 words.[39]

No letters or signed manuscripts written by Shakespeare survive. Shakespeare's six authenticated signatures are written in secretary hand, a style of handwriting that vanished by 1700, and he used breviographs to abbreviate his surname in three of them.[40] The appearance of Shakespeare's surviving signatures, which anti-Stratfordians have characterised as "scratchy" and "an illiterate scrawl", is taken as evidence that he was illiterate or just barely literate.[41]

Shakespeare's name as a pseudonym

In his surviving signatures William Shakespeare did not spell his name as it appears on most Shakespeare title pages. His surname was also spelled inconsistently in both literary and non-literary documents, with the most variation observed in those that were written by hand.[42] This is taken as evidence that he was not the same person who wrote the works attributed to William Shakespeare, and that the name was used as a pseudonym for the true author.[43]

Shakespeare's surname was hyphenated as "Shake-speare" or "Shak-spear" on the title pages of 15 of the 48 editions of Shakespeare's plays (16 were published with the author unnamed) and in two of the five editions of poetry published before the First Folio, as well as in one cast list and in six literary allusions published between 1594 and 1623. Of those 15 play editions, 13 are on the title pages of just three plays, Richard II, Richard III, and Henry IV, Part 1.[44] Such use of a hyphen is taken by many anti-Stratfordians to indicate a pseudonym,[45] with the reasoning that fictional descriptive names (such as "Master Shoe-tie" and "Sir Luckless Woo-all") were often hyphenated in plays, and pseudonyms such as "Tom Tell-truth" and the satirical variants of "Martin Marprelate" were also sometimes hyphenated.[46]

Reasons for the assertion that "Shakespeare" is a pseudonym vary, usually depending upon the social status of the candidate. Aristocrats such as Derby and Oxford supposedly used pseudonyms because of a prevailing "stigma of print", a social convention that restricted their literary works to private and courtly audiences—as opposed to commercial endeavours—at the risk of social disgrace if violated.[47] In the case of commoners, the reason was to avoid prosecution by the authorities—Bacon to avoid the consequences of advocating a more republican form of government;[48] Marlowe to avoid imprisonment or worse after faking his death and fleeing the country.[49]

Missing documentary evidence

Anti-Stratfordians claim that if the name on the plays and poems and literary references, "William Shakespeare", is assumed to be a pseudonym, then nothing in the documentary record left behind by William Shakespeare of Stratford explicitly names him as an author.[50] The evidence instead supports a career as a profit-seeking businessman and real estate investor, and any prominence he might have had in the London theatrical world (aside from his role as a front-man for the true author) was as a result of his money-lending activities, trading in theatrical properties such as costumes and old plays, and possibly as an actor of no great talent. All evidence for his literary career was created as part of the plan to shield the true author's identity.

All anti-Stratfordian theories reject the surface meanings of Elizabethan and Jacobean references to Shakespeare as a playwright and instead look for ambiguities and encrypted meanings. They identify him with such literary characters as the laughingstock Sogliardo in Ben Jonson’s Every Man Out of His Humour, the literary thief poet-ape in Jonson's poem of the same name, and the foolish poetry-lover Gullio in the university play The Return from Parnassus. Such characters are taken to indicate that the London theatrical world knew Shakespeare was a mere front for an unnamed author whose identity had to be shielded.[51]

Shakespeare's death

Shakespeare died 23 April 1616 in his home town of Stratford, leaving a signed will disposing of his large estate. The language of the will is mundane and unpoetic, and makes no mention of personal papers or books or poems or the 18 plays that remained unpublished at the time of his death, nor to shares in the new Globe Theatre. The only theatrical reference in the will—monetary gifts to fellow actors to buy mourning rings—was interlined after the will had been written, casting suspicion on the authenticity of the bequest.[52]

No records exist of Shakespeare being publicly mourned after he died, and no eulogies or poems commemorating the event were published until seven years later as part of the prefatory matter in the First Folio collection of his plays.[53] Oxfordians believe that the true playwright had died by 1609, the year Shake-speare's Sonnets appeared with a dedication written by Thomas Thorpe referring to "our ever-living Poet", an epithet that commonly eulogised a deceased warrior or poet as immortal in memory through his deeds.[54]

Shakespeare's funerary monument in Stratford consists of an effigy of him with pen in hand and an attached plaque praising his abilities as a writer. The earliest printed image of the effigy in Sir William Dugdale's Antiquities of Warwickshire (1656), differs greatly from its present appearance, and some anti-Stratfordians say that the figure originally portrayed a man clutching a grain sack or a wool sack that was later altered as part of the plan to conceal the identity of the true author.[55] Oxfordian Richard Kennedy proposes that the monument was originally built to honour John Shakespeare, William’s father, said by tradition to have been a "considerable dealer in wool".[56]

Evidence for Shakespeare's authorship

The mainstream view, to which nearly all academic Shakespeareans subscribe, is that the author referred to as "Shakespeare" was the same William Shakespeare who was born in Stratford-upon-Avon in 1564, travelled to London and became an actor and sharer (part-owner) of the Lord Chamberlain's Men (later the King's Men) acting company that owned the Globe Theatre, the Blackfriars Theatre, and exclusive rights to produce Shakespeare's plays from 1594 to 1642,[57] and who was allowed the use of the honorific "gentleman" after 1596 when his father, John Shakespeare, was granted a coat of arms, and who died in Stratford-upon-Avon in 1616.

Shakespeare scholars see no reason to suspect that the name was a pseudonym or that the actor was a front man for some other writer, since the records of the time all identify him as the writer, other playwrights such as Ben Jonson and Christopher Marlowe came from similar backgrounds, and no contemporary expressed doubt about Shakespeare’s authorship. In contrast to the methods used by anti-Stratfordians, Shakespeare scholars employ the same methodology to attribute works to the poet and playwright William Shakespeare as they use for other writers of the period: the historical record[58] and stylistic studies, and maintain that the methods used by many anti-Stratfordians to identify alternative candidates—such as reading the work as autobiography, finding coded messages and cryptograms embedded in the works, and concocting conspiracy theories to explain the lack of evidence for any writer but Shakespeare—are unreliable, unscholarly, and explain why more than 70 candidates[59] have been nominated as the "true" author.[60] They say that the idea that Shakespeare revealed himself in his work is a Romantic notion of the 18th and 19th centuries applied anachronistically to Elizabethan and Jacobean writers.[61]

Historical evidence for Shakespeare's authorship

The historical record is unequivocal in assigning the authorship of the Shakespeare canon to William Shakespeare.[62] In addition to his name appearing on the title pages of these poems and plays during William Shakespeare of Stratford's lifetime, his name was given as that of a well-known writer at least 23 times.[63] Several contemporaries corroborate the identity of the playwright as the actor, and explicit contemporary documentary evidence attests that the actor was the Stratford citizen.[64]

In 1598 Francis Meres named Shakespeare as a playwright and poet in his Palladis Tamia, referring to him as one of the authors by whom the "English tongue is mightily enriched". He names a dozen plays written by Shakespeare, including four which were never published in quarto: [Two] Gentlemen of Verona, [Comedy of] Errors, Love Labours Wonne, and King John, as well as ascribing to Shakespeare some of the plays that were published anonymously before 1598 – Titus Andronicus, Romeo and Juliet, and Henry IV. Meres mentions Edward de Vere, 17th Earl of Oxford, as being a writer of comedy in the same paragraph as he does Shakespeare. He refers to Shakespeare's "sugred Sonnets among his private friends" 11 years before the publication of the Sonnets.[65]

In the rigid social structure of Elizabethan England, the Stratford-born actor William Shakespeare was entitled to append the honorific "gentleman" after his name by right of his father being granted a coat of arms in 1596, an honorific conventionally designated by the title "Master" or its abbreviations "Mr." or "M." prefixed to the name.[66] This title was included in many contemporary references to Shakespeare during his lifetime, including official and literary records, and conclusively identifies William Shakespeare of Stratford as the "William Shakespeare" referred to as the author.[67]

Examples from Shakespeare's lifetime include two official stationers's entries, one dated 23 August 1600: "Andrew Wise William Aspley. Entred for their copies vnder the handes of the wardens Two bookes, the one call Muche a Doo about nothinge Thother the second parte of the history of Kinge Henry the iiijth with the humours of Sir John Falstaff: Wrytten by master Shakespere.xij d"; and the other dated 26 November 1607: "Nathanial Butter John Busby. Entred for their Copie under thandes of Sir George Buck knight and Thwardens A booke called. Master William Shakespeare his historye of Kinge Lear, as yt was played before the Kinges maiestie at Whitehall vppon Sainct Stephens night at Christmas Last, by his maiesties servantes playinge vsually at the Globe on the Banksyde vj d", which appeared on the title page of King Lear Q1 (1608) as "M. William Shak-speare: HIS True Chronicle Historie of the life and death of King Lear and his three Daughters."

His social status is also specifically referred to by his contemporaries in Epigram 159 by John Davies of Hereford in his The Scourge of Folly (1610): "To our English Terence, Mr. Will. Shake-speare"; Epigram 92 by Thomas Freeman in his Runne and A Great Caste (1614): "To Master W: Shakespeare"; and in historian John Stow's list of "Our moderne, and present excellent Poets" in Annales edited by Edmund Howes (1615): "M. Willi. Shakespeare gentleman".

After Shakespeare's death, Ben Jonson explicitly identified William Shakespeare, Gentleman, as the author in the title of his eulogy, "To the Memory of My Beloved the Author, Mr. William Shakespeare and What He Hath Left Us", published in the First Folio (1623). Other poets identified Shakespeare the gentleman as the author in the titles of their eulogies, also published in the First Folio: "Upon the Lines and Life of the Famous Scenic Poet, Master William Shakespeare" by Hugh Holland; and "To the Memory of the Deceased Author, Master W. Shakespeare" by Leonard Digges.

Personal testimonies by contemporaries

Both explicit personal testimony by his contemporaries and strong circumstantial evidence of personal relationships with contemporaries who interacted with him as an actor and playwright support Shakespeare's authorship.

Playwright and poet Ben Jonson knew Shakespeare from at least 1598, when the Lord Chamberlain's Men performed his play Every Man in his Humour at the Curtain Theatre with Shakespeare as a cast member. During his 1618–1619 walking tour of England and Scotland (four years before the First Folio publication), Jonson spent two weeks as a guest of the Scottish poet William Drummond, who recorded Jonson's often contentious comments about contemporaries, including Shakespeare, whom he criticised as wanting (i.e., lacking) "arte" and for mistakenly giving Bohemia a coast in The Winter's Tale.[68] In 1641, four years after Jonson's death, his private notes written during his later life were published in which he judged Shakespeare in a comment that he specifically states is intended for posterity (Timber or Discoveries). Although in his First Folio eulogy Jonson had lauded Shakespeare's painstaking poetic artistry,[69] in Timber he criticises Shakespeare's more casual approach to play writing. He praises Shakespeare as a person, writing "I lov'd the man, and doe honour his memory (on this side Idolatry) as much as any. Hee was (indeed) honest, and of an open, and free nature: had an excellent Phantsie, brave notions, and gentle expressions . . . . hee redeemed his vices, with his vertues. There was ever more in him to be praysed, then to be pardoned."

Shakespeare's surviving fellow actors John Heminges and Henry Condell knew and worked with Shakespeare for more than 20 years. In the 1623 First Folio, they professed that they had published the Folio "onely to keepe the memory of so worthy a Friend, & Fellow aliue, as was our Shakespeare, by humble offer of his playes".

Historian, antiquary, and book collector Sir George Buc served as Deputy Master of the Revels from 1603 and as Master of the Revels from 1610 to 1622. His duties were to supervise and censor plays for the public theatres, arrange court play performances, and after 1606 license plays for publication. Buc noted on the title page of George a Greene, the Pinner of Wakefield (1599), an anonymous play, that he had consulted Shakespeare on its authorship. Buc was meticulous in his efforts to attribute books and plays to the correct author, and in 1607 he personally licensed King Lear for publication as written by “Master William Shakespeare”.[70]

In 1602, Ralph Brooke, the York Herald, accused Sir William Dethick, the Garter King of Arms, of elevating 23 unworthy persons to the gentry, number four of whom was Shakespeare’s father, who had applied for arms 34 years earlier but had to wait for the success of his son before they were granted sometime before 1599. Brooke included a sketch of the Shakespeare arms, captioned "Shakespear ye Player by Garter." The grants, including John Shakespeare's, were defended by Dethick and Clarenceux King of Arms William Camden, the foremost antiquary of the time and life-long friend of Ben Jonson. In his Remaines Concerning Britaine, published in 1605 but completed two years earlier, Camden names Shakespeare the poet as one of the "most pregnant witts of these ages our times, whom succeeding ages may justly admire."[71]

Recognition by other playwrights and writers

In addition to Ben Jonson, other playwrights, including those who sold plays to Shakespeare's company, wrote about Shakespeare as a person and a playwright.

Two of the three Parnassus plays produced at St John's College, Cambridge near the turn of the 17th century mention Shakespeare as an actor, poet, and playwright without a university education. In The First Part of the Return from Parnassus, two separate characters refers to Shakespeare as "Sweet Mr. Shakespeare", and in The Second Part of the Return from Parnassus (1606), the anonymous playwright has the actor Kempe say to the actor Burbage, "Few of the university men pen plays well . . . . Why here's our fellow Shakespeare puts them all down."[72]

Prominent English actor, playwright, and author Thomas Heywood. An edition of The Passionate Pilgrim expanded with an additional nine poems written by Thomas Heywood with Shakespeare’s name on the title-page was published by William Jaggard in 1612. Heywood protested this piracy in his Apology for Actors (1612), adding that the author was "much offended with M. Jaggard (that altogether unknown to him) presumed to make so bold with his name." That Heywood stated with certainty that the author was unaware of the deception, and that Jaggard removed Shakespeare’s name from unsold copies even though Heywood didn't explicitly name him, indicates that Shakespeare was the offended author.[73] Elsewhere, in his poem "Hierarchie of the Blessed Angels" (1634) Heywood affectionately notes the nicknames his fellow playwrights had been known by. Of Shakespeare, he writes:

- Our moderne Poets to that passe are driuen,

- Those names are curtal'd which they first had giuen;

- And, as we wisht to haue their memories drown'd,

- We scarcely can afford them halfe their sound. . . .

- Mellifluous Shake-speare, whose inchanting Quill

- Commanded Mirth or Passion, was but Will.[74]

Playwright John Webster, in his dedication to White Divel (1612), wrote, "And lastly (without wrong last to be named), the right happy and copious industry of M. Shake-Speare, M. Decker, & M. Heywood, wishing what I write might be read in their light," here using the abbreviation "M." to denote the title "Master" that William Shakespeare of Stratford was entitled to use by virtue of being a titled gentleman.[75]

In a verse poem to Ben Jonson that has been dated to about 1608, poet and playwright Francis Beaumont alludes to several playwrights, including Shakespeare, about whom he wrote,

- "Heere I would let slippe

- (If I had any in mee) schollershippe,

- And from all Learninge keepe these lines as cleere

- as Shakespeares best are, which our heires shall heare

- Preachers apte to their auditors to showe

- how farr sometimes a mortall man may goe

- by the dimme light of Nature".[76]

Death of Shakespeare

The monument to Shakespeare that was erected in Holy Trinity Church, his local parish church in Stratford, sometime before 1623 bears a plaque with an inscription identifying him as a writer. The first two Latin lines translate to "In judgment a (Nestor) (Pylius), in genius a Socrates, in art a Maro (Virgil), the earth covers him, the people mourn him, Olympus possesses him." The monument was not only specifically referred to in the First Folio, but other early 17th-century records identify it as being a memorial to Shakespeare and transcribe the inscription.[77] Sir William Dugdale also included the inscription and identified the monument as commemorating the poet William Shakespeare in his Antiquities of Warwickshire (1656), but the engraving was done from a sketch made in 1634 and its inaccuracy is similar to other inaccurate monument portrayals in his work.[78]

The will of Shakespeare’s fellow actor, Augustine Phillips, executed 5 May 1605, proved 16 May 1605, bequeaths "to my Fellowe William Shakespeare a thirty shillings peece in gould, To my Fellowe Henry Condell one other thirty shillinge peece in gould . . .” William Shakespeare of Stratford-upon-Avon’s will, executed 25 March 1616, bequeaths "to my ffellowes John Hemynge Richard Burbage & Henry Cundell xxvj s viij d A peece to buy them Ringes." Numerous public records, including the royal patent of 19 May 1603 that chartered the King's Men, establishes that Philips, Heminges, Burbage, and Condell were fellow actors in the King's Men with William Shakespeare. Shakespeare's will also includes monetary bequests to buy mourning rings for his fellow actors and theatrical entrepreneurs Heminges, Burbage and Condell, two of whom later edited his collected plays. Anti-Stratfordians often try to cast suspicion on the bequests, which were interlined, saying that they were added later as part of the conspiracy, but the will was proved in the Prerogative Court of the Archbishop of Canterbury in London on 22 June 1616, and the original will was copied into the court register with the interlineations intact.

John Taylor was the first poet to mention in print the deaths of Shakespeare and Francis Beaumont in his 1620 poem The Praise of Hemp-seed.[79] Both had died within two months of each other four years earlier. Ben Jonson wrote a short poem "To the Reader" commending the First Folio Droeshout engraving of Shakespeare as a good likeness. Included in the prefatory commendatory verses was Jonson's lengthy eulogy "To the memory of my beloved, the Author Mr. William Shakespeare: and what he hath left us" in which he identifies Shakespeare as a playwright, a poet, and an actor, and writes:

- Sweet Swan of Avon! what a sight it were

- To see thee in our waters yet appeare,

- And make those flights upon the bankes of Thames,

- That so did take Eliza, and our James!

Here Jonson not only links the author to Shakespeare's home territory of Stratford-upon-Avon, but confirms his appearances at the courts of Elizabeth I and James I.[80]

Leonard Digges wrote the elegy "To the Memorie of the deceased Authour Maister W. Shakespeare" that was published in the Folio, in which he refers to "thy Stratford Moniment." Digges was raised in a village on the outskirts of Stratford-upon-Avon in the 1590s by his stepfather, William Shakespeare's friend Thomas Russell, who was appointed in Shakespeare's will as overseer to the executors.[81] William Basse wrote an elegy entitled "On Mr. Wm. Shakespeare" some time between 1616 and 1623, in which he suggests that Shakespeare should have been buried in Westminster Abbey next to Chaucer, Beaumont, and Spenser. This poem circulated very widely in manuscript and survives today in more than two dozen contemporary copies, several with the full title "On Mr. William Shakespeare, he died in April 1616," unambiguously referring to the Shakespeare of Stratford. Ben Jonson's eulogy responds directly to it, so it certainly was written before the publication of the First Folio in 1623.

Evidence for Shakespeare's authorship from his works

Shakespeare's are the most-studied secular works in history. Both textual and stylistic studies indicate that the author is compatible with the known biography of William Shakespeare of Stratford-upon-Avon.

No contemporary of Shakespeare ever referred to him as a learned writer or scholar. In fact, Ben Jonson and Francis Beaumont both refer to his lack of classical learning.[82] If a deeply erudite, university-trained playwright wrote the plays, it is hard to explain the many simple classical blunders in Shakespeare. Not only does he mistake the scansion of many classical names, in Troilus and Cressida he has Greeks and Trojans citing Plato and Aristotle a thousand years before their births, and in The Winter’s Tale, he gives "Delphos" for Delphi and confuses it with Delos, errors no scholar would make.[83] Later critics such as Samuel Johnson remarked that Shakespeare's genius lay not in his erudition, but from his "vigilance of observation and accuracy of distinction which books and precepts cannot confer; from this almost all original and native excellence proceeds."[84]

Shakespeare’s plays differ from those of the University Wits—Greene, Nash, Marlowe, Lyly, Lodge, and Peele—in that they are not larded with ostentatious displays of the writer’s learning to show mastery of Latin or of classical principles of drama, with the exceptions of co-authored plays such as the Henry VI series and Titus Andronicus. Instead, his classical allusions rely on the Elizabethan grammar school curriculum, which provided a rigorous regimen of Latin instruction from the age of 7 until the age of 14. The Latin curriculum began with William Lily’s Latin grammar Rudimenta Grammatices, which was by law the sole Latin grammar to be used in grammar schools, and progressed to Caesar, Livy, Virgil, Horace, Ovid, Plautus, Terence, and Seneca, all of which are quoted and echoed in the Shakespearean canon. Almost alone among his contemporary peers, Shakespeare’s plays are full of phrases from grammar school texts and pedagogy, including caricatures of school masters. Lily's Grammar is referred to in the plays by characters such as Demetrius and Chiron in Titus Andronicus (4.10), Tranio in The Taming of the Shrew, the schoolmaster Holofernes of Love's Labour's Lost (5.1) in a parody of a grammar-school lesson, Sir Toby Belch in Twelfth Night, and Sir Hugh Evans, another schoolmaster who in Merry Wives of Windsor (4.1) gives the boy William a lesson in Latin, parodying Lily. Shakespeare alluded not only to grammar school but also to the petty school that children attended from the age of 5 to 7 to learn to read, a prerequisite for grammar school.[85]

Beginning in 1987, Ward Elliott, who was sympathetic to Oxford as the author, and Robert J. Valenza supervised a continuing study of Shakespeare’s works based on a quantitative comparison of Shakespeare’s stylistic habits (known as stylometrics) using computer programs to compare them to the works of 37 authors who had been claimed to be the true author at one time or another. The study, known as the Claremont Shakespeare Clinic, was last held in the spring of 2010.[86] The tests determined that Shakespeare’s work shows consistent, countable, profile-fitting patterns, suggesting that he was a single individual, not a committee, and that he used more hyphens, feminine endings, and open lines and fewer relative clauses than most of the writers with whom he was compared. The result determined that none of the other tested claimants’ work could have been written by Shakespeare, nor could Shakespeare have been written by them, eliminating all of the claimants—including Oxford, Bacon, and Marlowe—as the true authors of the Shakespeare works.[87]

Much like today, literary styles went in and out of fashion, and Shakespeare's style was no exception. His late plays, such as The Winter's Tale, The Tempest, and Henry VIII, are written in a radically different style from the Elizabethan-era plays, in a style used by other Jacobean playwrights.[88] In addition, after the King's Men began using the Blackfriars Theatre for performances in 1609, Shakespeare's late plays were written to accommodate playing on a smaller stage with more music, dancing, and more evenly divided acts to allow for trimming the candles used for stage lighting.[89]

Studies show that an artist's creativity is responsive to the milieu in which the artist works, and especially to conspicuous political events.[90] Dean Keith Simonton, a researcher into the factors of musical and literary creativity, especially Shakespeare’s, has conducted several studies and concludes "beyond a shadow of a doubt" that the consensus play chronology is roughly in the correct order, and that Shakespeare's works exhibit stylistic development over the course of his career, consistent with the works of other artistic geniuses.[91] Simonton's study, published in 2004, examined the correlation between the thematic content of Shakespeare’s plays and the political context in which they would have been written according to traditional and Oxfordian datings. When lagged two years, the Stratfordian chronologies yielded substantially meaningful associations between thematic and political context, while the Oxfordian chronologies yielded no relationships, no matter how they were lagged.[92] Simonton, who declared his Oxfordian sympathies in the article and had expected the results to support Oxford’s authorship, concluded that "that expectation was proven wrong."[93]

Shakespeare co-authored half of his last 10 plays, collaborating closely with other writers for the stage. Some anti-Stratfordian supporters of other candidates, particularly Oxfordians, say that those plays were finished by other playwrights after the death of the true author. But textual evidence from the late plays indicate that Shakespeare's collaborators were not always aware of what Shakespeare had done in a previous scene, and that they were following a rough outline rather than working from an unfinished script left by a long-dead playwright. For example, in Two Noble Kinsmen (1612–1613), written with John Fletcher, Shakespeare has two characters meet and leaves them on stage at the end of one scene, yet Fletcher has them act as if they were meeting for the first time in the following scene.[94]

History of the authorship question

Shakespeare's singularity and bardology

Apart from adulatory tributes attached to his works and common in eulogies to poets, Shakespeare was not deified as the world's greatest writer in the century and a half following his death.[95] His reputation was that of a good playwright and poet among many others of his age.[96] In fact, until the actor David Garrick mounted the Shakespeare Stratford Jubilee in 1769, Beaumont and Fletcher's plays dominated popular taste after the theatres reopened in 1660, with Ben Jonson and Shakespeare's plays vying for second place.[97] Excluding a handful of minor 18th century satirical and allegorical references,[98] there is no suggestion over this period that anyone else had written the works.[99] The emergence of the Shakespeare authorship question had to wait until he was regarded as the English national poet in a class by himself.[100]

Precursors of doubt

In time Shakespeare came to be singled out as both a transcendent genius and untutored rustic,[101] and by the beginning of the 19th century, adulation in the form of bardolatry was in full swing.[102] Yet uneasiness also began to emerge over the dissonance between Shakespeare's godlike reputation and the humdrum facts of his biography.[103] Although his views were to remain orthodox, Ralph Waldo Emerson around 1845 expressed the underlying question in the air about Shakespeare by admitting he could not reconcile Shakespeare's verse with the image of a jovial actor and theatre manager.[104] The rise of historical criticism, which had begun to challenge the authorial unity of Homer's epics and the historicity of the Bible, also fueled the emerging puzzlement over Shakespeare's authorship, in one critic's view becoming "an accident waiting to happen."[105] In particular, David Strauss's historical investigation of Jesus[106] had shocked public opinion for its scepticism over historical reportage and influenced debate about Shakespeare's image. In 1848, Samuel Mosheim Schmucker endeavoured to rebut Strauss's doubts about the historicity of Christ by applying the same techniques satirically[107] to the records of Shakespeare's life in his Historic Doubts Respecting Shakespeare, Illustrating Infidel Objections Against the Bible.[108] Schmucker, who never doubted that Shakespeare was Shakespeare, unwittingly anticipated and rehearsed many of the later anti-Stratfordian arguments.[109]

Open dissent and the first alternative candidate

Shakespeare’s authorship was first openly questioned in the pages of Colonel Joseph C.Hart’s The Romance of Yachting (1848).[110] Four years later Dr. Robert W. Jameson published "Who Wrote Shakespeare" anonymously in the Chambers's Edinburgh Journal,[111] followed in 1856 by Delia Bacon’s unsigned "William Shakspeare and His Plays; An Enquiry Concerning Them"[112] in Putnam's Monthly.

Since 1845, Bacon had been mapping out a theory that the plays attributed to Shakespeare were actually written by a coterie of men, including Sir Walter Raleigh as the main writer with Edmund Spenser, under the leadership of Sir Francis Bacon for the purpose of inculcating an advanced political and philosophical system for which they themselves could not publicly assume the responsibility.[114] Francis Bacon was the first alternative author proposed in print by William Henry Smith in a pamphlet published September 1856, Was Lord Bacon the Author of Shakspeare's Plays? A Letter to Lord Ellesmere.[115] The following year Delia Bacon, with the help of Nathaniel Hawthorne, published her book outlining her theory, The Philosophy of the Plays of Shakspere Unfolded.[116] Some ten years later, after the American Civil War, Judge Nathaniel Holmes of Kentucky published the 600-page The Authorship of Shakespeare supporting Smith's theory,[117] and the idea began to spread widely. By 1884 it had produced more than 250 books, and Smith predicted the war against the Shakespeare hegemony had almost been won by the Baconians after a 30-year battle.[118] Two years later the Francis Bacon Society was founded in England to mop up any areas of lingering resistance.[119] The society still survives and publishes a journal, Baconiana, to further its mission.

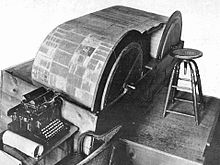

Ciphers became important to the theory, with thick books such as Ignatius L. Donnelly's The Great Cryptogram (1888), promoting the approach.[120] Dr. Orville Ward Owen constructed a "cipher wheel", a 1,000-foot long strip of canvas on which he had pasted the works of Shakespeare and other writers and mounted on two parallel wheels so he could quickly collate pages with key words as he turned them for decryption.[121] In his multi-volume Sir Francis Bacon's Cipher Story (1893), he discovered Bacon's autobiography embedded in Shakespeare's plays, which revealed that Bacon was actually the secret son of Queen Elizabeth, yet more reason to conceal his authorship from the public.[122]

None of these assaults on Shakespeare's authorship went unanswered by academe. In 1857 English critic George Henry Townsend published William Shakespeare Not an Impostor, criticising the slovenly scholarship, false premises, specious parallel passages, and erroneous conclusions of the earliest anti-Stratfordians.[123]

Shakespeare on trial, part 1

Perhaps because of Bacon's legal background, the Shakespeare authorship question has often been tested by recourse to the framework of trial by jury in both mock and real trials. The first such occasion was conducted over 15 months in 1892–93, and the results of the debate were published in the Boston monthly The Arena. Ignatius Donnelly was one of the plaintiffs, while F. J. Furnivall formed part of the defence. The 25 member-jury included Henry George, Edmund Gosse, and Henry Irving. The verdict came down heavily in favour of the man from Stratford.[124] In 1916, a Cook Country Circuit Court judge, Richard Tuthill, found against Shakespeare, and positively determined that Francis Bacon was the author of the works. Damages of $5,000 were awarded the Baconian advocate, Colonel George Fabyan. In the ensuing uproar, Tuthill rescinded his decision, and another judge, Judge Frederick A. Smith, dismissed the case.[125]

Unearthing proof

More than one critic has noted the Baconian inclination to dig in churches, river beds, and tombs for evidence.[126]

With the help of Ralph Waldo Emerson, Delia Bacon travelled to England in 1853 to seek evidence for her theory.[127] Disdaining archival research, she sought instead to unearth buried manuscripts she believed would validate her theories. She unsuccessfully tried to persuade the caretaker to open Bacon's tomb at St Albans.[128] From Bacon's letters, she deciphered instructions for locating a will and archives beneath Shakespeare's Stratford gravestone that would prove the works were Bacon's, but she failed to prise up the stone slab after spending several nights in the chancel trying to summon her courage.[129]

In 1907, Orville Ward Owen used his famous cipher wheel to decode detailed instructions revealing the site where a box containing Bacon's literary treasures and proof of his authorship had been buried in the Wye river by Chepstow Castle on the Duke of Beaufort's property. His expensively rented dredging machinery failed to retrieve the concealed manuscripts.[131] That same year his former assistant, Elizabeth Wells Gallup, now financed by George Fabyen, likewise set sail for England, believing she had decoded a different message by means of a bilateral cipher revealing that Bacon's secret manuscripts were hidden behind some panels in Canonbury Tower, Islington.[132]

In the 1920s, Walter Conrad Arensberg, convinced that Bacon had willed the key to his cipher to the Rosicrucians, who apparently survived under the protection of the Church of England, accused the Dean of Lichfield of being privy to the secret, and of hiding information that Bacon and his mother had been buried in the Lichfield Chapter house. He waged a long campaign to photograph the obscure grave.[133] Mrs Maria Bauer convinced herself that Bacon manuscripts had been imported into Jamestown, Virginia in 1653, and could be found in the Bruton Vault at Williamburg. She gained permission in the late 1930s to excavate, but the alarmed authorities quickly withdrew her permit.[134] In 1938 Roderick Eagle gained permission to open the tomb of Edmund Spenser to search for a poem he believed was thrown in to prove Bacon was Shakespeare, but found only an old skull and some nondescript bones.[135]

Other candidates emerge

Other candidates besides Bacon began to receive attention. In 1895 attorney Wilbur Gleason Zeigler published the novel It Was Marlowe: A Story of the Secret of Three Centuries. In the preface he makes the case that Marlowe survived his 1593 death and wrote Shakespeare's plays.[136] The German literary critic Karl Bleibtreu supported the nomination of the 5th Earl of Rutland, Roger Manners in 1907.[137]

Unaffiliated anti-Stratfordians began to appear. British barrister Sir George Greenwood sought to disqualify William Shakespeare from the authorship in his The Shakespeare Problem Restated (1908), but withheld support for any alternative authors, therefore sanctioning the search for candidates other than Bacon and setting the stage for the rise of other candidates such as Marlowe, Stanley, Manners, and Oxford.[138] The American humorist Mark Twain, influenced by Greenwood,[139] revealed his anti-Stratfordian beliefs in Is Shakespeare Dead? (1909), favouring Bacon as the true author.[140]

In 1913 John M. Robertson published The Baconian Heresy: A Confutation, refuting the contention that Shakespeare had expert legal knowledge by showing that legalisms pervaded Elizabethan and Jacobean literature.[141] After World War II, Professor Abel Lefranc, a renowned authority on French and English literature, revived William Stanley, 6th Earl of Derby as the author, using on biographical evidence he gleaned from the plays and poems.[142]

With the appearance of John Thomas Looney's Shakespeare Identified (1920),[143] Edward de Vere, 17th Earl of Oxford quickly ascended as the most popular alternative author.[144] Two years later Looney and Greenwood founded The Shakespeare Fellowship, an international organization to promote discussion and debate on the authorship question, which later changed its mission to propagate the Oxfordian theory.[145] In 1923 Archie Webster published "Was Marlowe the Man?" in The National Review, claiming that Marlowe wrote the works of Shakespeare and that the Sonnets were an autobiographical account of his survival and banishment.[146] In 1932 Allardyce Nicoll announced the discovery of a manuscript that appeared to establish that James Wilmot was the earliest proponent of Baconian theory,[147] but recent findings have exposed the paper as a forgery that was probably designed to revive Bacon's flagging popularity in the face of Oxford's ascendancy as the most popular candidate.[148]

Another candidate for the true bard, Sir Edward Dyer, was revealed in 1943 by writer Alden Brooks in his Will Shakspere and the Dyer's hand.[149] Six years earlier Brooks had eliminated Shakespeare as the playwright by inventing the profession of Elizabethan "play broker" and arguing that brokering the plays was his true role in the deception, a view that was later adapted by Oxfordians.[150]

Shakespeare, Oxford, and Bacon spoke to Percy Allen from the spirit world in 1947 through the use of the medium Hester Dowden in his Talks with Elizabethans Revealing the Mystery of "William Shakespeare" (1947), with the verdict that Oxford was the main writer with the other two merely touching up.[151] Allen had previously revealed that Oxford and Elizabeth were lovers and that the actor Shakespeare was their son in his Anne Cecil, Elizabeth, and Oxford (1934).[152]

Oxfordism and anti-Stratfordism declined in popularity and visibility during World War II and afterward, as academics attacked their methodology as unscholarly and their conclusions as ridiculous.[153] Copious archival research had failed to turn up the expected confirmation of Oxford or anyone else as the true author, and publishers lost interest in repetitious books containing the same claims, based on what anti-Stratfordians asserted to be overwhelming circumstantial evidence. To bridge this lack of evidence, Oxfordians joined the Baconians in finding myriad hidden clues in the Shakespeare canon placed there by Oxford to tip off future researchers.[154]

To try to revive flagging interest in Oxford, in 1952 Dorothy and Charlton Ogburn Sr published a 1,300-page This Star of England, now regarded as a classic Oxfordian text.[155] They uncovered the Elizabethan state secret that the "fair youth" of the sonnets was Henry Wriothesley, 3rd Earl of Southampton, the product of a passionate love affair between Oxford and the Queen, and that the "Shakespeare" plays were written by Oxford to memorialise their love affair. The Ogburns found many parallels between Oxford's life and the works, claiming that the "play Hamlet is straight biography."[156] This became known as the "Prince Tudor theory", and revived the movement enough to permit the establishment of The Shakespeare Oxford Society in the U. S. two years later.

Also in the mid-1950s Broadway press agent Calvin Hoffman revived the Marlovian theory with the publication of The Murder of the Man Who Was "Shakespeare" (1955).[157] The next year he took a page out of the Baconian book and went to England to search for documentary evidence about Marlowe that he thought might be buried in his literary patron Sir Thomas Walsingham's tomb.[158]

A series of critical academic books and articles, however, held in check any appreciable growth of anti-Stratfordism. American cryptologists William and Elizebeth Friedman won the Folger Shakespeare Library Literary Prize of $1000 in 1955 for a definitive study that is considered to have disproven the long-standing claims that the works of Shakespeare contain hidden ciphers that disclose Bacon's or any other candidate's secret authorship. The study was condensed and published as The Shakespeare Ciphers Examined (1957). Closely in its wake, four major works were issued surveying the history of the anti-Stratfordian phenomenon from a critical orthodox perspective, The Poacher from Stratford (1958) by Frank Wadsworth, Shakespeare and His Betters (1958), by Reginald Churchill, The Shakespeare Claimants (1962), by N. H. Gibson, and Shakespeare and His Rivals: A Casebook on the Authorship Controversy (1962), by George L. McMichael and Edgar M. Glenn. In 1959 The American Bar Association Journal published a series of articles and letters on the authorship controversy, later anthologised as Shakespeare Cross-Examination (1961).

In 1968 the newsletter of The Shakespeare Oxford Society reported that "the missionary or evangelical spirit of most of our members seems to be at a low ebb, dormant, or non-existent."[159] In 1974, membership stood at 80. Freelance writer Charlton Ogburn, Jr., elected president of the society in 1976, promptly began a campaign to bypass the academic establishment, which he considered to be an "entrenched authority" that aimed to "outlaw and silence dissent in a supposedly free society," a situation that he termed "an intellectual Watergate". He proposed fighting for public recognition in the media by portraying Oxford as a candidate standing on equal footing with Shakespeare.[160] In 1985 he published his 900-page The Mysterious William Shakespeare: the Myth and the Reality, and by framing the issue as one of fairness and equal time in the atmosphere of conspiracy that permeated America after Watergate, he learnt how to use the media to circumnavigate the academy and appeal directly to the public.[161] He secured Oxford as the most popular theory, kick-starting the modern revival of the movement, based on seeking publicity through moot court trials, media debates, television, and later the Internet, including Wikipedia.[162]

Shakespeare on trial, part 2

Ogburn, Jr., considered that academics were best challenged by recourse to law, and the Oxfordians had their day in court when three justices of the Supreme Court of the United States convened a one-day moot court to hear the case 25 September 1987. The trial was structured so that literary experts would not be represented, but the burden of proof was put upon the Oxfordians. The justices determined that the case was based on a conspiracy theory, and that the reasons given for this conspiracy were both incoherent and unpersuasive. Although Ogburn took the verdict as a "clear defeat" for his cause, Oxfordian columnist Joseph Sobran recognised that the trial had effectively dismissed any other Shakespeare authorship contender from the public mind and provided legitimacy for Oxford.[163] A retrial was organised the next year in the United Kingdom in the expectancy that this decision could be reversed. Presided over by three Lords, the court was held in London's Inner Temple 26 November 1988. On this occasion Shakespearean scholars argued their case, and the outcome confirmed the American verdict, but publicity was generated and attracted potential Oxfordian converts.[164]

Television, magazines, and the Internet

In 1989 the PBS Frontline broadcast "The Shakespeare Mystery", paraphrasing the title of Ogburn's book and exposing the romantic view of Oxford-as-Shakespeare to more than 3.5 million viewers in the U.S. alone.[165] This was followed in 1962 by a three-hour Frontline teleconference, "Uncovering Shakespeare: an Update", moderated by William F. Buckley, Jr., which closed with an animation of Shakespeare's Stratford monument crumbling to reveal a portrait of Oxford.[166]

In 1991 The Atlantic Monthly published a print debate between Tom Bethell ("The Case for Oxford") and Irvin Matus ("The Case for Shakespeare"), which was followed in 1999 by a similar print debate in Harper's Magazine between anti-Stratfordians and Stratfordians, "The Ghost of Shakespeare".

Beginning in the decade of the 1990s Oxfordians and other anti-Stratfordians increasingly turned to the Internet to promulgate their theories, including creating and composing various Wikipedia articles about the candidates and the arguments.[167]

On 14 April 2007 the Shakespeare Authorship Coalition issued an online petition, the "Declaration of Reasonable Doubt about the Identity of William Shakespeare", coinciding with Brunel University's announcement of a one-year Master of Arts programme in Shakespeare authorship studies. The coalition intends to enlist broad public support so that by 2016, the 400th anniversary of Shakespeare's death, the academic Shakespeare establishment will be forced to acknowledge that legitimate grounds for doubting Shakespeare's authorship exist.[168] More than 1,200 sceptics signed the petition by the end of 2007. By December 2010, 1,874 had signed the petition, 330 of them current or former academics. A week later the New York Times published a survey of 265 American Shakespeare professors on the Shakespeare authorship question in the "Education" section. To the question whether there is good reason to question Shakespeare's authorship, 6% answered "yes", and 11% "possibly". When asked their opinion of the topic, 61% chose "A theory without convincing evidence" and 32% "A waste of time and classroom distraction".[169]

Filmmaker Roland Emmerich announced in 2009 that his next film will be about Oxford-as-Shakespeare based on a script he bought eight years earlier. The film, Anonymous, starring Rhys Ifans and Vanessa Redgrave, will be released in the United States 23 September 2011. It portrays Oxford as the illegitimate son of Queen Elizabeth who became the queen's lover as an adult, with whom he sires his own half-brother/son, Henry Wriothesley, 3rd Earl of Southampton, to whom he dedicates the Sonnets.

Shakespeare scholar James Shapiro surveyed the authorship question in Contested Will: Who Wrote Shakespeare?, in which he criticises academe for ignoring the topic and effectively surrendering the field to anti-Stratfordians.[170]

Alternative candidates

Although they overlap, the types of evidence marshalled to support the various alternative candidates fall into four broad categories: historical conjectures, parallel passages, biographical allusions extracted from the works, and hidden messages found by means of ciphers, cryptograms, or codes.

Sir Francis Bacon

The leading candidate of the 19th century was one of the great intellectual figures of Jacobean England, Sir Francis Bacon, lawyer, philosopher, essayist and scientist. The case for Bacon relies upon historical and literary conjectures and cryptographical revelations found in the works that disclose his authorship.[171]

William Henry Smith was the first to propose Bacon as the author in September 1856 in Was Lord Bacon the Author of Shakspeare's Plays? A Letter to Lord Ellesmere,[172] using such parallel passages as Bacon's Poetry is nothing else but feigned history to Shakespeare's The truest poetry is the most feigning (AYLI 3.3.19-20), and Bacon's He wished him not to shut the gate of your Majesty's merry to Shakespeare's The gates of mercy shall be all shut up (H5 3.3.10).[173] After discovering hidden political meanings in the plays and parallels between those ideas and Bacon's known works, Delia Bacon proposed him as the leader of a group of disaffected philosopher-politicians who tried to promote republican ideas to counter the despotism of the Tudor-Stewart monarchies through the medium of the public stage.[174] Later supporters of Bacon found similarities between a great number of specific phrases and aphorisms from the plays and those written down by Bacon in his wastebook, the Promus. In 1883 Mrs Henry Pott edited Bacon's Promus, finding 4,400 parallels of thought or expression between Shakespeare and Bacon,[175] such as Rome / Romeo; Good morrow / Good morrow; Sweet for speech in the morning / What early tongue so sweet saluteth me?; Lodged next / Where care lodges; and Uprouse / Thou art uproused by some distemperature. This method was used to expand Bacon's canon to include the works of Spenser, Watson, Greene, Lodge, Peele, Marlowe, Lyly and Nashe.[176]

In a letter addressed to John Davies, Bacon closes "so desireing you to bee good to concealed poets", which his supporters take as Bacon referring to himself.[177] Sir Toby Matthew, in a letter to Bacon (after 1621) wrote that: "The most prodigious wit that ever I knew of my nation and of this side of the sea is of your Lordship's name, though he be known by another."[178] Baconians take this to be a reference to Bacon's pseudonymous authorship of Shakespeare's works. They also point to Bacon's comment that play-acting was used by the ancients "as a means of educating men's minds to virtue,"[179] and argue that while he outlined both a scientific and moral philosophy in The Advancement of Learning (1605), only the first part was published under his name during his lifetime. His moral philosophy, including a revolutionary politico-philosophic system of government, was concealed in the Shakespeare plays because of the danger to the monarchical government, but was not discovered until the mid-19th century by Delia Bacon.[180]

The great number of legal allusions used by Shakespeare demonstrate his expertise in the law, Baconians say, and Bacon not only became Queen's Counsel in 1596, but was appointed Attorney General in 1613. Bacon also paid for and helped write speeches for a number of entertainments, including masques and dumb shows, although he is not known to have authored a play. His only attributed verse consists of seven metrical psalters, following Sternhold and Hopkins.[181]

Since Bacon was knowledgeable about ciphers,[182] early Baconians suspected that he left his signature encrypted in the Shakespeare canon. In the late-19th and early-20th centuries Baconians discovered that the works were riddled with ciphers supporting Bacon as the true author. In 1881, Mrs. C. F. Ashwood Windle, inspired by Delia Bacon's reference to a cipher, discovered carefully worked-out jingles in each play that revealed Bacon as the author.[183] She in turn inspired other cryptologists, most notably Ignatius Donnelly, who also discovered probative cryptograms in the plays.[184] He in turn inspired Orville Ward Owen, who deciphered Bacon's complete biography from the works as well as revealing that Francis Bacon was the secret son of Queen Elizabeth and the Earl of Leicester.[185] Baconian cryptogram-hunting flourished well into the 20th century, and in 1905 Walt Whitman biographer Dr. Isaac Hull Platt discovered that the Latin word honorificabilitudinitatibus, found in Love's Labour's Lost, is an anagram of Hi ludi F. Baconis nati tuiti orbi ("These plays, the offspring of F. Bacon, are preserved for the world.").

Edward de Vere, 17th Earl of Oxford

Edward de Vere, 17th Earl of Oxford was hereditary Lord Great Chamberlain. He followed his grandfather and father in patronising a company of players,[186] including bands of musicians, tumblers, and performing animals. Although none of his theatrical works survive, De Vere was recognised as a playwright, one of the "best for comedy amongst us", by Francis Meres, as well as an important courtier poet.[187]

The case for Oxford relies upon historical and literary facts and conjectures, biographical coincidences, and cryptographical revelations found in the works that disclose his authorship.

Although Oxford had been nominated previously and was even a part of Bacon's authorship coterie,[188] an English school-teacher, J. Thomas Looney was the first to lay out a comprehensive case for his authorship.[189] Instead of finding coded tutorials for republicanism in the plays à la Delia Bacon, Looney found allegories based on barely-disguised autobiography to promote the return to medieval values of social class and authoritarian monarchical rule.[190] He identified personality characteristics in Shakespeare’s works—especially Hamlet—that painted the author as an eccentric, profligate, aristocratic poet, a drama and sporting enthusiast with a classical education who had travelled to Italy.[191] Oxford alone among the aristocratic candidates had been praised by his contemporaries as an accomplished poet,[192] and Looney discovered stylistic and thematic parallels between his extant works and Shakespeare's,[193] which enabled him to identify Oxford as the true author. But Looney considered the most critical part of the case to be the close affinity he found between the poetry of Oxford and that of Shakespeare in the use of motifs and subjects, phrasing, and rhetorical devices.[194] After Looney's Shakespeare Identified was published in 1920, Oxford rapidly overtook Bacon to become the most popular alternative candidate, and remains so to this day.[195]

Although Oxford died in 1604 with 10 Shakespeare plays yet to be written according to the most widely accepted chronology, Oxfordians date the later plays earlier and say that all the contemporary allusions or later sources were added by other hands during revision long after Oxford's death.[196] In addition, the publisher's dedication in Shakespeare's Sonnets (1609) wishes "all happiness and that eternity promised by our ever-living poet" to an unknown "Mr. W. H.", which is taken by some scholars to refer to the author of the sonnets. Oxfordians say that the phrase "ever-living" implies that the author is dead.[197]

Shakespeare's works as written by Oxford are thought to contain correspondences to Oxford's life and are read as coded autobiography, and literal readings of certain sonnets are taken to refer to incidents in Oxford's life.[198] For example, the speaker in Sonnet 37 says he is "made lame by fortune's spite" in 37 and in 89 tells the addressee to "Speak of my lameness, and I straight will halt". In a 25 March 1595 letter to Burghley, Oxford wrote "I will attend Your Lordship as well as a lame man may at your house."[199]

No documentary evidence connecting Oxford to the authorship of the works has been found,[200] so codes and ciphers have been found in the works to support the theory, such as the anagram "E. Vere" embedded in the works more than 1,700 times in the words "ever", "every", and "never". These same veiled signatures have been found by Oxfordians in the works of Marlowe, George Gascoigne, Sir John Harrington, Edmund Spenser, and others, identifying them all as pseudonyms used by Oxford.[201] A device from Henry Peacham’s Minerva Britanna (1612) depicts a hand behind a curtain that has written the Latin motto MENTE VIDEBOR ("By the mind I shall be seen"). This was first used to support Bacon’s candidacy, but is seen by Oxfordians as a clue to Oxford’s hidden authorship. By interpreting the final full stop as the beginning of an “I”, from the resulting letters an anagram is constructed that when rearranged reveals TIBI NOM. DE VERE ("Thy Name is De Vere").[202]

Oxford’s desire for anonymity is attributed to the stigma of print, a convention that aristocratic authors could not publicly take credit for writing popular plays.[203] An alternative reason for the use of the “Shakespeare” pseudonym is the theory that Oxford became Queen Elizabeth's lover as an adult, and they had a son, Henry Wriothesley, 3rd Earl of Southampton, to whom he dedicates the Sonnets. This is known as the "Prince Tudor" theory, promulgated by Dorothy and Charlton Ogburn Sr in their 1,300-page This Star of England, which is regarded as a classic Oxfordian text.[204] A variation of this, the "Prince Tudor Part II" theory, has Oxford as the illegitimate son of Queen Elizabeth, and their offspring Southampton Oxford’s half brother/son, the heir to the throne and whom Oxford immortalised as the "fair youth" of the sonnets.[205]

Christopher Marlowe

The case for Marlowe relies upon historical conjectures predicated on the speculation that the government records of his assassination on 20 May 1593 are part of a hoax, and that he lived on to write the Shakespeare canon from exile. The purpose of this deception was to allow Marlowe to escape arrest and almost certain execution on charges of subversive atheism, and flee the country to live in France and Italy. Thomas Walsingham, Marlowe's secret lover,[206] arranged the imposture, and also acted as the go-between to deliver the manuscripts to the actor Shakespeare.[207] Literary conjectures, historical and biographical coincidences, and cryptographic revelations are found in the works to support this scenario.

A brilliant poet and dramatist, Marlowe was born in the same social class as Shakespeare two months earlier than he, attended Cambridge University, and pioneered the use of blank verse in Elizabethan drama. He was first nominated as a candidate in 1884 as part of a group, but was promoted to that of a single author in 1895.[208] His candidacy was revived in 1955 and has gained popularity so that he is considered the nearest rival to Oxford.[209]

That the very first work linked to the name William Shakespeare—Venus and Adonis—was registered with the Stationers' Company on 18 April 1593 with no named author, and was then printed with William Shakespeare's name signed to the dedication and on sale just 13 days after Marlowe's reported death is one such coincidence.[210] Lists of verbal correspondences also have been compiled to support the theory.[211]

William Stanley, 6th Earl of Derby

William Stanley, 6th Earl of Derby, was first proposed in 1891 by James Greenstreet.[212] The case for Derby relies upon historical and literary conjectures and biographical coincidences. He is often mentioned as a leader or participant in the "group theory" of Shakespearean authorship.[213] Derby was born three years before Shakespeare and died in 1642, so his lifespan fits the consensus dating of the works.[214] His initials were W. S., and he was known to sign himself "Will", which qualified him to write the punning "Will" sonnets.[215]

Derby's older brother, Ferdinando Stanley, 5th Earl of Derby, formed a group of players, the Lord Strange's Men, some of whose members eventually joined the King's Men, one of the companies most associated with Shakespeare. In 1582 William Derby supposedly made a grand continental tour, travelling through France, Navarre, Italy, Turkey, and other countries. Love's Labour's Lost is set in King Ferdinand's Court of Navarre and the play may be based on events that happened there between 1578 and 1584.[216]

In 1599 the Jesuit spy George Fenner reported in two letters that Derby "is busye in penning commodyes for the common players."[217] That same year Stanley was reported as financing one of London's two children's drama companies, Paul's Boys and his own, Derby's Men, known for playing at the Boar's Head Inn, which played multiple times at court in 1600 and 1601.[218]

Stanley married Elizabeth de Vere, whose maternal grandfather was William Cecil, thought by some critics to be the basis of the character of Polonius in Hamlet. E. A. J. Honigmann argued that the first production of A Midsummer Night's Dream was performed at Stanley's wedding banquet.[219] Derby was associated with William Herbert, 3rd Earl of Pembroke and his brother Philip Herbert, Earl of Montgomery and later 4th Earl of Pembroke, the "Incomparable Pair" to whom William Shakespeare's First Folio is dedicated. When Derby released his estates to his son James around 1628–29, he named Pembroke and Montgomery as trustees.

Footnotes

- ^ McMichael & Glenn 1962, p. 56.

- ^ Wadsworth 1958, p. 65.

- ^ Kathman 2003, p. 621: "...in fact, antiStratfordism has remained a fringe belief system for its entire existence. Professional Shakespeare scholars mostly pay little attention to it, much as evolutionary biologists ignore creationists and astronomers dismiss UFO sightings."; Schoenbaum 1991, p. 450: "A great many of the schismatics are (as we have seen) distinguished in fields other than literary scholarship, and their ignorance of fact and method is as dismaying as their non-specialist love of Shakespeare's plays is touching."; Nicholl 2010, p. 4 quotes Gail Kern Paster, director of the Folger Shakespeare Library: "To ask me about the authorship question ... is like asking a palaeontologist to debate a creationist's account of the fossil record."; Nelson 2004, p. 151: "I do not know of a single professor of the 1,300-member Shakespeare Association of America who questions the identity of Shakespeare ... Among editors of Shakespeare in the major publishing houses, none that I know questions the authorship of the Shakespeare canon."; Carroll 2004, pp. 278–9: "I am an academic, a member of what is called the 'Shakespeare Establishment,' one of perhaps 20,000 in our land, professors mostly, who make their living, more or less, by teaching, reading, and writing about Shakespeare—and, some say, who participate in a dark conspiracy to suppress the truth about Shakespeare.... I have never met anyone in an academic position like mine, in the Establishment, who entertained the slightest doubt as to Shakespeare's authorship of the general body of plays attributed to him. Like others in my position, I know there is an anti-Stratfordian point of view and understand roughly the case it makes. Like St. Louis, it is out there, I know, somewhere, but it receives little of my attention."; Pendleton 1994, p. 21: "Shakespeareans sometimes take the position that to even engage the Oxfordian hypothesis is to give it a countenance it does not warrant. And, of course, any Shakespearean who reads a hundred pages on the authorship question inevitably realizes that nothing he can say will prevail with those persuaded to be persuaded otherwise."; Gibson 2005, p. 30.

- ^ Bate 2002, p. 106: "The Shakespeare authorship controversy is an epiphenomenon, a secondary symptom, a consequence of the extraordinary elevation of the dramatist's status that occurred in the eighteenth century. Before this, the conditions simply did not exist for a controversy."

- ^ Law 1965, p. 184; Kroeber 1993, p. 369.

- ^ Bate 2002, p. 106; Dobson 2001, p. 31: "By the middle of the 19th century, the Authorship Controversy was an accident waiting to happen. In the wake of Romanticism, especially its German variants, such transcendent, quasi-religious claims were being made for the supreme poetic triumph of the Complete Works that it was becoming well-nigh impossible to imagine how any mere human being could have written them all. At the same time the popular understanding of what levels of cultural literacy might have been achieved in 16th-century Stratford was still heavily influenced by a British tradition of Bardolatry (best exemplified by David Garrick’s Shakespeare Jubilee) which had its own nationalist reasons for representing Shakespeare as an uninstructed son of the English soil …"

- ^ Shapiro 2010, pp. 2–3 (4); McCrea 2005, p. 13.