Sakoku: Difference between revisions

| Line 27: | Line 27: | ||

The direct trigger which caused Sakoku was the [[Shimabara Rebellion]] of 1637-1638, an uprising of 40,000 mostly Christian peasants. In the |

The direct trigger which caused Sakoku was the [[Shimabara Rebellion]] of 1637-1638, an uprising of 40,000 mostly Christian peasants. In the |

||

very bloody aftermath, the shogunate accused these missionaires of instigating the rebellion, expelled them from the country, and strictly banned the |

very bloody aftermath, the shogunate accused these missionaires of instigating the rebellion, expelled them from the country, and strictly banned the |

||

religion on |

religion on penalty of death. The remaining Japanese Christians, mostly in Nagasaki, formed underground communities called [[Kakure Kirishitan]]. |

||

All contact with the outside world became strictly regulated by the shogunate. Dutch traders were permitted to continue commerce in |

All contact with the outside world became strictly regulated by the shogunate. Dutch traders were permitted to continue commerce in |

||

Japan only by agreeing not to engage in missionary activities. |

Japan only by agreeing not to engage in missionary activities. |

||

Revision as of 06:05, 20 April 2007

This article may require copy editing for grammar, style, cohesion, tone, or spelling. (January 2007) |

This article appears to contradict the article History of Japan#Seclusion. |

Sakoku (Japanese: 鎖国, literally "country in chains" or "lock up of country") was the foreign relations policy of Japan under which no foreigner or Japanese could enter or leave the country on penalty of death. The policy was enacted by the shogunate under Tokugawa Iemitsu in 1641 and remained in effect until 1853. It was still illegal to leave Japan until the Meiji restoration. The term "Sakoku" originates from the work "Sakoku-ron" published by Tadao Shituki in 1801. Shituki invented the word while translating the works of the 17th-century German traveller Engelbert Kaempfer concerning Japan. Note that under the Sakoku policy, Japan was not completely isolated. Rather, it was a system in which all commerce and foreign relations were strictly regulated by the shogunate.

The policy stated that the only foreign influence permitted was the Dutch factory (trading post) at Dejima in Nagasaki. Trade with China was also handled at Nagasaki. In addition, trade with Korea was conducted via Tsushima Province (today part of Nagasaki Prefecture) and with the Ryūkyū Kingdom via Satsuma Province (in present-day Kagoshima Prefecture). Apart from these direct commercial contacts in peripheral provinces, all of these countries sent regular tributary missions to the shogunate's seat in Edo. As the emissaries travelled across Japan, Japanese citizens had a glimpse of foreign cultures.

Trade under Sakoku

Japan traded at this time with five different entities, through four "gateways." Through the Matsumae fief in Hokkaidō (then called Ezo), they traded with the Ainu people. Through the Sō clan daimyo of Tsushima, they had relations with Joseon Dynasty Korea. The Dutch East India Company was permitted to trade at Nagasaki, alongside private Chinese traders, who also traded with the Ryūkyū Kingdom. Ryūkyū, a semi-independent kingdom for nearly all of the Edo period, was controlled by the Shimazu family of daimyo in Satsuma Domain. Tashiro Kazui has shown that trade between Japan and these entities was divided into two kinds of trade: Group A in which he places China and the Dutch, "whose relations fell under the direct jurisdiction of the Bakufu at Nagasaki" and Group B, represented by the Korean Kingdom and the Ryūkyū Kingdom, "who dealt with Tsushima (the Sō clan) and Satsuma (the Shimazu clan) domains respectively."[1]

These two different groups of trade basically reflected a pattern of incoming and outgoing trade. The outgoing trade flowing out from Japan to Korea and the Ryūkyū Kingdom, eventually being brought from those places to China. In the Ryukyu Islands and Korea, the clans in charge of trade with the Ryūkyū Kingdom and Korea built trading towns outside Japanese territory--where commerce actually took place.[2] Due to the necessity for Japanese subjects to travel to and from these trading posts, this trade resembled something of an outgoing trade, with Japanese subjects making regular contact with foreign traders in essentially extraterritorial land. Trade with Chinese and Dutch traders in Nagasaki took place on an island called Dejima, separated away from the city by a small strait; foreigners could not enter Japan from Dejima, nor could Japanese enter Dejima, without special permissions or authority.

Terminology

Trade in fact prospered during this period, and though relations and trade were restricted to certain ports, the country was far from closed. In fact, as the shogunate expelled the Portuguese, they simultaneously engaged in discussions with Dutch and Korean representatives to ensure that the overall volume of trade did not suffer[2]. Thus, it has become increasingly common in scholarship in recent decades to refer to the foreign relations policy of the period not as sakoku, implying a totally secluded, isolated, and "closed" country, but by the term kaikin (海禁, "maritime restrictions") used in documents at the time, and derived from the similar Chinese concept hai jin[3].

Rationale

It is generally regarded that the shogunate enforced the Sakoku policy in order to remove the colonial and religious influence of primarily Spain and Portugal. Some historians also claim that the conservative and xenophobic shogun of the time Iemitsu Tokugawa simply disliked European culture. The shogunate had already begun to percieve the increasing number of Catholic Christian converts in southern Japan as a threat to their authority. Protestant English and Dutch traders reinforced this perception by accusing the Spainish and Portugese missionaries of spreading the religion systematically, as part of a claimed policy of culturally dominating and colonizing Asian countries. The number of Christians in Japan had been steadily rising due to the efforts of missionaries such as Francis Xavier, and daimyo converts. The direct trigger which caused Sakoku was the Shimabara Rebellion of 1637-1638, an uprising of 40,000 mostly Christian peasants. In the very bloody aftermath, the shogunate accused these missionaires of instigating the rebellion, expelled them from the country, and strictly banned the religion on penalty of death. The remaining Japanese Christians, mostly in Nagasaki, formed underground communities called Kakure Kirishitan. All contact with the outside world became strictly regulated by the shogunate. Dutch traders were permitted to continue commerce in Japan only by agreeing not to engage in missionary activities.

The Sakoku policy was also a way of controlling commerce between Japan and other nations, as well as asserting its new place in the East Asian hierarchy—one that helped push Japan away from tributary relations that had existed between itself and China for many centuries before. Later on, the Sakoku policy was the main safeguard against the total depletion of Japanese mineral resources—such as silver and copper—to the outside world. However, while silver exportation through Nagasaki was controlled by the Bakufu to the point of stopping all exportation, the exportation of silver through Korea continued in relatively high quantities.[1]

The way Japan kept abreast of Western technology during this period was by studying medical and other texts in the Dutch language obtained through Dejima. This process was called "Rangaku" (Dutch studies). It became obsolete after the country was opened and the Sakoku policy collapsed. Thereafter, many Japanese students (e.g. Kikuchi Dairoku) were sent to study in foreign countries, and many foreign employees were employed in Japan (see o-yatoi gaikokujin).

This policy ended with the Convention of Kanagawa in response to demands made by Commodore Perry.

Challenges to seclusion

Many isolated attempts to end Japan's seclusion were made by expanding Western powers during the 18th and 19th century. American, Russian and French ships all attempted to engage in relationship with Japan, but were rejected.

- In 1778, a merchant from Yakutsk by the name of Pavel Lebedev-Lastoschkin arrived in Hokkaidō with a small expedition. He offered gifts, and politely asked to trade in vain.

- In 1787, La Perouse (1741–1788) navigated in Japanese waters. He visited the Ryukyu islands and the strait between Hokkaidō and Honshū, naming it after himself.

- In 1791, two American ships commanded by the American explorer Kendrick stopped for 11 days on Kii Oshima island, south of the Kii Peninsula. He was the first known American to have visited Japan. He apparently planted an American flag and claimed the islands, although accounts of his visit in Japan are nonexistent.

- From 1797 to 1809, several American ships traded in Nagasaki under the Dutch flag, upon the request of the Dutch who were not able to send their own ships because of their conflict against Britain during the Napoleonic Wars[4]:

- In 1797 US Captain William Robert Stewart, commissioned by the Dutch from Batavia, took the ship Eliza of New York to Nagasaki, Japan, with a cargo of Dutch trade goods.

- In 1803 William Robert Stewart returned on board a ship named "The Emperor of Japan" (the stolen and renamed "Eliza of New York"), entered Nagasaki harbour and tried in vain to trade through the Dutch enclave of Dejima.

- Another American captain John Derby of Salem, tried in vain to open Japan to the opium trade.

- In 1804 a Russian envoy named Nikolai Rezanov, sailed into Nagasaki, to request trade exchanges. The Bakufu refused the request, and the Russians attacked Sakhalin and the Kuril islands during the following three years, prompting the Bakufu to build up defences in Ezo.

- In 1808, the British frigate HMS Phaeton, raiding on Dutch shipping in the Pacific, sailed into Nagasaki under a Dutch flag, demanding and obtaining supplies by force of arms.

- In 1811, the Russian naval lieutenant Vasily Golovnin landed on Kunashiri Island, and was arrested by the Bakufu and imprisoned for 2 years.

- In 1825, following a proposal by Takahashi Kageyasu, the Bakufu issued an "Order to Drive Away Foreign Ships" (Ikokusen uchiharairei, also known as the "Ninen nashi", or "No second thought" law), ordering coastal authorities to arrest or kill foreigners coming ashore.

- In 1837, an American businessman in Canton, named Charles W. King saw an opportunity to open trade by trying to return to Japan three Japanese sailors (among them, Otokichi) who had been shipwrecked a few years before on the coast of Oregon. He went to Uraga Channel with Morrison, an unarmed American merchant ship. The ship was fired upon several times, and finally sailed back unsuccessfully.

- In 1842, following the news of the defeat of China in the Opium War and internal criticism following the Morisson incident, the Bakufu responded favourably to foreign demands for the right to refuel in Japan by suspending the order to execute foreigners and adopting the "Order for the Provision of Firewood and Water" (Shinsui kyuyorei).

- In 1844, a French naval expedition under Captain Fornier-Duplan visited Okinawa on April 28, 1844. Trade was denied, but Father Forcade was left behind with a translator.

- In 1845, whaling ship Manhattan (1843) rescued 22 Japanese shipwrecked sailors. Captain Mercator Cooper was allowed into Edo Bay, where he stayed for four days and met with the Governor of Edo and several high officers representing The Emperor. They were given several presents and allowed to leave unmolested, but told never to return.

- In 1846, Commander James Biddle, sent by the United States Government to open trade, anchored in Tokyo Bay with two ships, including one warship armed with 72 cannons, but his demands for a trade agreement remained unsuccessful.

- In 1848, Half-Scottish/Half-Chinook Ranald MacDonald pretended to be shipwrecked on the island of Rishiri in order to gain access to Japan. He was sent to Nagasaki, where he stayed for 10 months and became the first English teacher in Japan. Upon his return to America, MacDonald made a written declaration to Congress, explaining that the Japanese society was well policed, and the Japanese people well behaved and of the highest standard.

- In 1848, Captain James Glynn sailed to Nagasaki, leading at last to the first successful negotiation by an American with "Closed Country" Japan. James Glynn recommended to the United States Congress that negotiations to open Japan should be backed up by a demonstration of force, thus paving the way to Perry's expedition.

- In 1849, the British Navy's HMS Mariner entered Uraga Harbour to conduct a topographical survey. Onboard was the Japanese castaway Otokichi, who acted as a translator. To avoid problems with the Japanese authorities, he disguised himself as Chinese, and said that he had learned Japanese from his father, allegedly a businessman who had worked in relation with Nagasaki.

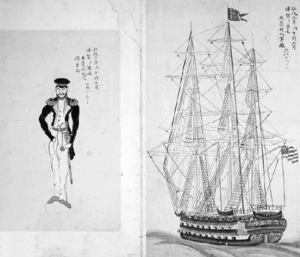

These largely unsuccessful attempts continued until, on July 8, 1853, Commodore Matthew Perry of the U.S. Navy with four warships: Mississippi, Plymouth, Saratoga, and Susquehanna steamed into the Bay of Edo (Tokyo) and displayed the threatening power of his ships' Paixhans guns. He demanded that Japan open to trade with the West. These ships became known as the kurofune, the Black Ships.

End of seclusion

The following year, at the Convention of Kanagawa (March 31, 1854), Perry returned with seven ships and forced the Shogun to sign the "Treaty of Peace and Amity", establishing formal diplomatic relations between Japan and the United States. Within five years Japan had signed similar treaties with other western countries. The Harris Treaty was signed with the United States on July 29, 1858. These treaties were widely regarded by Japanese intellectuals as unequal, having been forced on Japan through gunboat diplomacy, and as a sign of the West's desire to incorporate Japan into the imperialism that had been taking hold of the continent. Among other measures, they gave the Western nations unequivocal control of tariffs on imports and the right of extraterritoriality to all their visiting nationals. They would remain a sticking point in Japan's relations with the West up to the turn of the century.

Missions to the West

Several missions were sent abroad by the Bakufu, in order to learn about Western civilization, revise treaties, and delay the opening of cities and harbour to foreign trade.

A Japanese Embassy to the United States was sent in 1860, onboard the Kanrin Maru. An Embassy to Europe was sent in 1862, and a Second Embassy to Europe in 1863. Japan also sent a delegation and participated to the 1867 World Fair in Paris.

Other missions, distinct from those of the Shogunate, were also sent to Europe, such as the Chōshū Five, and missions by the fief of Satsuma.

References

- ^ a b Tashiro, Kazui. "Foreign Relations During the Edo Period: Sakoku Reexamined." Journal of Japanese Studies. Vol. 8, No. 2, Summer 1982.

- ^ a b Toby, Ronald. State and Diplomacy in Early Modern Japan. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1984 Cite error: The named reference "Toby" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Toby, Ronald (1977). "Reopening the Question of Sakoku: Diplomacy in the Legitimation of the Tokugawa Bakufu", Journal of Japanese Studies. Seattle: Society for Japanese Studies.

- ^ K. Jack Bauer, A Maritime History of the United States: The Role of America's Seas and Waterways, University of South Carolina Press, 1988., p. 57

See also

- Isolationism

- Hai jin (海禁) - Maritime restrictions; kaikin in Japanese.