Spanish flu: Difference between revisions

boldness, people! |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Flu}} |

{{Flu}} |

||

The '''1918 flu pandemic''' (commonly referred to as the '''Spanish flu''') was a [[Pandemic Severity Index|category 5]] influenza pandemic caused by an unusually severe and deadly [[Influenza A virus]] [[Strain (biology)|strain]] of subtype [[H1N1]]. Many of its victims were healthy young adults, in contrast to most influenza outbreaks which predominantly affect juvenile, elderly, or otherwise weakened patients. |

The '''1918 flu pandemic''' (commonly but misleadingly referred to as the '''Spanish flu''') was a [[Pandemic Severity Index|category 5]] influenza pandemic caused by an unusually severe and deadly [[Influenza A virus]] [[Strain (biology)|strain]] of subtype [[H1N1]]. Many of its victims were healthy young adults, in contrast to most influenza outbreaks which predominantly affect juvenile, elderly, or otherwise weakened patients. |

||

The Spanish flu pandemic lasted from 1918 to 1919, spreading even to the [[Arctic]] and remote Pacific islands. While older estimates put the number of killed at 40–50 million people, current estimates are that 50 million to 100 million people worldwide died, possibly more than that taken by the [[Black Death]]. This extraordinary toll resulted from the extremely high infection rate of up to 50% and the extreme severity of the symptoms, suspected to be caused by [[cytokine storm]]s. Between 2 and 20% of those infected by Spanish flu died, as opposed to the normal flu epidemic [[mortality rate]] of 0.1%. In some remote Inuit villages, mortality rates of nearly 100% were recorded. Unusually, the epidemic mostly killed young adults, with 99% of pandemic influenza deaths occurring in people under 65, and more than half in young adults 20 to 40 years old. |

The Spanish flu pandemic lasted from 1918 to 1919, spreading even to the [[Arctic]] and remote Pacific islands. While older estimates put the number of killed at 40–50 million people, current estimates are that 50 million to 100 million people worldwide died, possibly more than that taken by the [[Black Death]]. This extraordinary toll resulted from the extremely high infection rate of up to 50% and the extreme severity of the symptoms, suspected to be caused by [[cytokine storm]]s. Between 2 and 20% of those infected by Spanish flu died, as opposed to the normal flu epidemic [[mortality rate]] of 0.1%. In some remote Inuit villages, mortality rates of nearly 100% were recorded. Unusually, the epidemic mostly killed young adults, with 99% of pandemic influenza deaths occurring in people under 65, and more than half in young adults 20 to 40 years old. |

||

Revision as of 10:23, 10 December 2007

| Influenza (flu) |

|---|

|

The 1918 flu pandemic (commonly but misleadingly referred to as the Spanish flu) was a category 5 influenza pandemic caused by an unusually severe and deadly Influenza A virus strain of subtype H1N1. Many of its victims were healthy young adults, in contrast to most influenza outbreaks which predominantly affect juvenile, elderly, or otherwise weakened patients.

The Spanish flu pandemic lasted from 1918 to 1919, spreading even to the Arctic and remote Pacific islands. While older estimates put the number of killed at 40–50 million people, current estimates are that 50 million to 100 million people worldwide died, possibly more than that taken by the Black Death. This extraordinary toll resulted from the extremely high infection rate of up to 50% and the extreme severity of the symptoms, suspected to be caused by cytokine storms. Between 2 and 20% of those infected by Spanish flu died, as opposed to the normal flu epidemic mortality rate of 0.1%. In some remote Inuit villages, mortality rates of nearly 100% were recorded. Unusually, the epidemic mostly killed young adults, with 99% of pandemic influenza deaths occurring in people under 65, and more than half in young adults 20 to 40 years old.

The disease was first observed at Queens, New York, U.S. on March 11, 1918. The Allies of World War I came to call it the Spanish Flu, primarily because the pandemic received greater press attention in Spain than in the rest of the world, as Spain was not involved in the war and had not imposed wartime censorship.[1]

Scientists have used tissue samples from frozen victims to reproduce the virus for study. Given the strain's extreme virulence there has been controversy regarding the wisdom of such research. Among the conclusions of this research is that the virus kills via a cytokine storm, which explains its unusually severe nature and the unusual age profile of its victims.

Mortality

The global mortality rate from the 1918/1919 pandemic is not known, but is estimated at 2.5 to 5% of the human population, with 20% or more of the world population suffering from the disease to some extent. Influenza may have killed as many as 25 million in its first 25 weeks (in contrast, AIDS killed 25 million in its first 25 years). Older estimates say it killed 40–50 million people[3] while current estimates say 50 million to 100 million people worldwide were killed.[4] This pandemic has been described as "the greatest medical holocaust in history" and may have killed as many people as the Black Death.[5]

An estimated 7 million died in India, about 2.78% of India's population at the time. In the Indian Army, almost 22% of troops who caught the disease died of it (cite needed). In the U.S., about 28% of the population suffered, and 500,000 to 675,000 died. In Britain as many as 250,000 died; in France more than 400,000. In Canada approximately 50,000 died. Entire villages perished in Alaska and southern Africa. In Australia an estimated 12,000 people died and in the Fiji Islands, 14% of the population died during only two weeks, and in Western Samoa 22%.

This huge death toll was caused by an extremely high infection rate of up to 50% and the extreme severity of the symptoms, suspected to be caused by cytokine storms.[3] Indeed, symptoms in 1918 were so unusual that initially influenza was misdiagnosed as dengue, cholera, or typhoid. One observer wrote, "One of the most striking of the complications was hemorrhage from mucous membranes, especially from the nose, stomach, and intestine. Bleeding from the ears and petechial hemorrhages in the skin also occurred."[4] The majority of deaths were from bacterial pneumonia, a secondary infection caused by influenza, but the virus also killed people directly, causing massive hemorrhages and edema in the lung.[2]

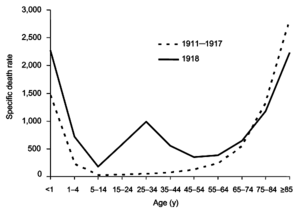

The unusually severe disease killed between 2 and 20% of those infected, as opposed to the more usual flu epidemic mortality rate of 0.1%.[2][4] Another unusual feature of this pandemic was that it mostly killed young adults, with 99% of pandemic influenza deaths occurring in people under 65, and more than half in young adults 20 to 40 years old.[6] This is unusual since influenza is normally most deadly to the very young (under age 2) and the very old (over age 70).

History

While World War I did not cause the flu, the close quarters and mass movement of troops quickened its spread. Researchers speculate that the soldiers' immune systems were weakened by the stresses of combat and chemical attacks, increasing their susceptibility to the disease.

A large factor in the spread of the disease was the increased amount of travel. The modernization of transportation made it easier for sailors to spread the disease more quickly and to a wider range of communities.

Two poems, dedicated to the Spanish flu, were popular in those days:

I had a little bird,

Its name was Enza,

I opened the window,

And in-flew-enza.

-American Skipping Rhyme circa 1918

Obey the laws

And wear the gauze.

Protect your jaws

From septic paws.

Patterns of fatality

The influenza strain was unusual in that this pandemic killed many young adults and otherwise healthy victims — typical influenzas kill mostly infants (aged 0-2 years), the old, and the immunocompromised. Another oddity was that this influenza outbreak struck hardest in summer and fall (in the Northern Hemisphere). Typically, influenza is worse in the winter months.

People without symptoms could be struck suddenly and within hours be too feeble to walk; many died the next day. Symptoms included a blue tint to the face and coughing up blood caused by severe obstruction of the lungs. In some cases, the virus caused an uncontrollable hemorrhaging that filled the lungs, and patients drowned in their body fluids. In still others, the flu caused an uncontrollable loss of bowel functions and the victim would die from losing critical intestinal lining.

In fast-progressing cases, mortality was primarily from pneumonia, by virus-induced consolidation. Slower-progressing cases featured secondary bacterial pneumonias, and there may have been neural involvement that led to mental disorders in a minority of cases. Some deaths resulted from malnourishment and even animal attacks in overwhelmed communities.

Devastated communities

While in most places less than one-third of the population was infected, only a small percentage of whom died, in a number of towns in several countries entire populations were wiped out.

Even in areas where mortality was low, those incapacitated by the illness were often so numerous as to bring much of everyday life to a stop. Some communities closed all stores or required customers not to enter the store but place their orders outside the store for filling. There were many reports of places with no health care workers to tend the sick because of their own ill health and no able-bodied grave diggers to bury the dead. Mass graves were dug by steam shovel and bodies buried without coffins in many places.

Unaffected locales

In Japan, 257,363 deaths were attributed to influenza by July 1919, giving an estimated 0.425% mortality rate, much lower than nearly all other Asian countries for which data are available. The Japanese government severely restricted maritime travel to and from the home islands when the pandemic struck. The only sizeable inhabited place with no documented outbreak of the flu in 1918–1919 was the island of Marajó at the mouth of the Amazon River in Brazil. In the Pacific, American Samoa[7] and the French colony of New Caledonia [8] also succeeded in preventing even a single death from influenza through effective quarantines.

Spanish flu research

One theory is that the virus strain originated at Fort Riley, Kansas, by two genetic mechanisms — genetic drift and antigenic shift — in viruses in poultry and swine which the fort bred for local consumption. But evidence from a recent reconstruction of the virus suggests that it jumped directly from birds to humans, without traveling through swine.[9] On October 5, 2005, researchers announced that the genetic sequence of the 1918 flu strain, a subtype of avian strain H1N1, had been reconstructed using historic tissue samples.[10][11][12] On 18 January 2007, Kobasa et al reported that infected monkeys (Macaca fascicularis) exhibited classic symptoms of the 1918 pandemic and died from a cytokine storm.[13]

Famous victims

- Guillaume Apollinaire, French poet († November 9, 1918)

- Felix Arndt, American pianist († October 16, 1918)

- Sophie Freud, daughter of Austrian psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud, († 1920)

- Harold Gilman, British painter († February 12, 1919)

- Henry G. Ginaca, American engineer, inventor of the Ginaca machine († October 19, 1918)

- Charles Tomlinson Griffes, American composer († April 8, 1920)

- Phoebe Hearst, mother of William Randolph Hearst, († April 13, 1919)

- Francisco Marto, Fátima child († April 4, 1919)

- Jacinta Marto, Fátima child († February 20, 1920)

- Edmond Rostand, French dramatist, best known for his play Cyrano de Bergerac, († December 2, 1918)

- Egon Schiele, Austrian painter († October 31, 1918). His wife Edith, who was six months pregnant, succumbed to the disease only three days before.

- Yakov Sverdlov, Bolshevik party leader and official of pre-USSR Russia († March 16 1919)

- Max Weber, German political economist and sociologist († June 14, 1920)

References

- ^ See: Talk:Spanish_flu#Origin of the name "spanish flu" [not specific enough to verify]

- ^ a b c Taubenberger, J (2006). "1918 Influenza: the mother of all pandemics". Emerg Infect Dis. 12 (1): 15–22. PMID 16494711.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) Cite error: The named reference "Taubenberger" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). - ^ a b Patterson, KD (1991). "The geography and mortality of the 1918 influenza pandemic". Bull Hist Med. 65 (1): 4–21. PMID 2021692.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b c Knobler S, Mack A, Mahmoud A, Lemon S (ed.). "1: The Story of Influenza". The Threat of Pandemic Influenza: Are We Ready? Workshop Summary (2005). Washington, D.C.: The National Academies Press. pp. 60–61.

{{cite book}}: External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link) - ^ Potter, CW (2006). "A History of Influenza". J Appl Microbiol. 91 (4): 572–579. PMID 11576290.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Simonsen, L (1998). "Pandemic versus epidemic influenza mortality: a pattern of changing age distribution". J Infect Dis. 178 (1): 53–60. PMID 9652423.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ World Health Organization Writing Group (2006). "Nonpharmaceutical interventions for pandemic influenza, international measures". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Emerging Infectious Diseases (EID) Journal. 12 (1): 189.

- ^ Sometimes a virus contains both avian adapted genes and human adapted genes. Both the H2N2 and H3N2 pandemic strains contained avian flu virus RNA segments. "While the pandemic human influenza viruses of 1957 (H2N2) and 1968 (H3N2) clearly arose through reassortment between human and avian viruses, the influenza virus causing the 'Spanish flu' in 1918 appears to be entirely derived from an avian source (Belshe 2005)." (from Chapter Two : Avian Influenza by Timm C. Harder and Ortrud Werner, an excellent free on-line Book called Influenza Report 2006 which is a medical textbook that provides a comprehensive overview of epidemic and pandemic influenza.)

- ^ Special report at Nature News: The 1918 flu virus is resurrected, Published online: 5 October 2005; doi:10.1038/437794a

- ^ Taubenberger, Jeffery K. (2005). "Characterization of the 1918 influenza virus polymerase genes". Nature. 437: 889–893. doi:10.1038/nature04230.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Also: Tumpey, Terrence M. (2005). "Characterization of the Reconstructed 1918 Spanish Influenza Pandemic Virus". Science. 310: 77–80. doi:10.1126/science.1119392.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Aberrant innate immune response in lethal infection of macaques with the 1918 influenza virus Nature. 18 January 2007;445:319

Further reading

- Barry, John M. (2004). The Great Influenza: The Epic Story of the Greatest Plague in History. Viking Penguin. ISBN 0-670-89473-7.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help)

- Crosby, Alfred W. (1990). America's Forgotten Pandemic: The Influenza of 1918. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-38695-0.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help)

- Johnson, Niall (2006). Britain and the 1918-19 Influenza Pandemic: A Dark Epilogue. London and New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-36560-0.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help)

- Johnson, Niall (2003). "Measuring a pandemic: Mortality, demography and geography". Popolazione e Storia: 31–52.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help)

- Johnson, Niall (2003). "Scottish 'flu – The Scottish mortality experience of the "Spanish flu". Scottish Historical Review. 83 (2): 216–226.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help)

- Johnson, Niall (2002). "Updating the accounts: global mortality of the 1918–1920 'Spanish' influenza pandemic". Bulletin of the History of Medicine. 76: 105–15.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)

- Little, Jean (2007). If I Die Before I Wake: The Flu Epidemic Diary of Fiona Macgregor, Toronto, Ontario, 1918. Dear Canada. Markham, Ont.: Scholastic Canada. ISBN 9780439988377.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help)

- Noymer, Andrew (2000). "The 1918 Influenza Epidemic's Effects on Sex Differentials in Mortality in the United States". Population and Development Review. 26 (3): 565–581. ISSN 0098-7921.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)

- Oxford JS, Sefton A, Jackson R, Innes W, Daniels RS, Johnson NP (2002). "World War I may have allowed the emergence of "Spanish" influenza". The Lancet infectious diseases. 2 (2): 111–4. PMID 11901642.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Oxford JS, Sefton A, Jackson R, Johnson NP, Daniels RS (1999). "Who's that lady?". Nat. Med. 5 (12): 1351–2. doi:10.1038/70913. PMID 10581070.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Phillips, Howard (2003). The Spanish Flu Pandemic of 1918: New Perspectives. London and New York: Routledge.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)

- Rice, Geoffrey W. (1993). "Pandemic Influenza in Japan, 1918-1919: Mortality Patterns and Official Responses". Journal of Japanese Studies. 19 (2): 389–420. ISSN 0095-6848.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)

- Rice, Geoffrey W. (2005). Black November: the 1918 Influenza Pandemic in New Zealand. Canterbury University Press. ISBN 1-877257-35-4.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help)CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)

- Tumpey TM, García-Sastre A, Mikulasova A; et al. (2002). "Existing antivirals are effective against influenza viruses with genes from the 1918 pandemic virus". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99 (21): 13849–54. doi:10.1073/pnas.212519699. PMID 12368467.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

External links

- Video from Expert Panel Discussion on Avian Flu

- Nature "Web Focus" on 1918 flu, including new research

- Influenza Pandemic on stanford.edu

- Article: The Deadliest Fall

- Influenza 1918 in the United States on pbs.org

- Secrets of the Dead: Killer Flu (PBS)

- Flu by Eileen A. Lynch. The devastating effect of the Spanish flu in the city of Philadelphia, PA, USA

- Dialog: An Interview with Dr. Jeffery Taubenberger on Reconstructing the Spanish Flu

- The Deadly Virus - The Influenza Epidemic of 1918, by the National Archives and Records Administration (see actual pictures and records of the time).

- The 1918 Influenza Pandemic in New Zealand - includes recorded recollections of people who lived through it

- Experts Unlock Clues to Spread of 1918 Flu Virus - The New York Times

- PBS - recovery of flu samples from Alaskan flu victims

- An Avian Connection as a Catalyst to the 1918-1919 Influenza Pandemic

- Alaska Science Forum - Permafrost Preserves Clues to Deadly 1918 Flu

- Pathology of Influenza in France, 1920 Report

- "Deadly secret of 1918 flu virus unmasked", Cosmos magazine, September 2006

- Yesterday's News blog, 1918 newspaper account on impact of flu on Minneapolis

- "Lethal secrets of 1918 flu virus" BBC News, January 2007

- "Study uncovers a lethal secret of 1918 influenza virus" University of Wisconsin - Madison, January 17, 2007

- "The site of origin of the 1918 influenza pandemic and its public health implications" Journal of Translational Medicine, January 20, 2004