Nose art: Difference between revisions

m →Subject matter: space |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 10: | Line 10: | ||

<!--comment out deleted image: [[Image:Spad SXIII.jpg|thumb|150px|SPAD S.XIII of [[1st Operations Group#Army Air Corps|94h Aero Squadron]], marked as Capt. [[Eddie Rickenbacker]]'s aircraft.]]--> |

<!--comment out deleted image: [[Image:Spad SXIII.jpg|thumb|150px|SPAD S.XIII of [[1st Operations Group#Army Air Corps|94h Aero Squadron]], marked as Capt. [[Eddie Rickenbacker]]'s aircraft.]]--> |

||

Some World War I examples became famous, including the "Hat in the Ring" of the USAAF [[1st Operations Group#Army Air Corps|94h Aero Squadron]] (attributed to Lt. Johnny Wentworth)<ref>[http://afhra.maxwell.af.mil/ Air Force Historical Research Agency<!-- Bot generated title -->]</ref> or the "Kicking Mule" of the [[1st Operations Group#Army Air Corps|95th Aero Squadron]]. This followed the official policy, established by the [[American Expeditionary Forces|AEF]]'s Chief of the Air Service, [[Brigadier]] [[Benjamin Foulois]], on 6 May 1918, insisting units have their own distinct, readily identifiable [[insigne]].<ref>[http://afhra.maxwell.af.mil/ Air Force Historical Research Agency<!-- Bot generated title -->]</ref> Nose art was not common practice during Depression-era Army Air Corps austerity, but it would be during the global crisis of [[World War II]] that the practice of naming aircraft flourished, with some merely christened, others artistically adorned with cartoons and pin-ups. Puns and references to popular culture were common subjects.<ref |

Some World War I examples became famous, including the "Hat in the Ring" of the USAAF [[1st Operations Group#Army Air Corps|94h Aero Squadron]] (attributed to Lt. Johnny Wentworth)<ref>[http://afhra.maxwell.af.mil/ Air Force Historical Research Agency<!-- Bot generated title -->]</ref> or the "Kicking Mule" of the [[1st Operations Group#Army Air Corps|95th Aero Squadron]]. This followed the official policy, established by the [[American Expeditionary Forces|AEF]]'s Chief of the Air Service, [[Brigadier]] [[Benjamin Foulois]], on 6 May 1918, insisting units have their own distinct, readily identifiable [[insigne]].<ref>[http://afhra.maxwell.af.mil/ Air Force Historical Research Agency<!-- Bot generated title -->]</ref> Nose art was not common practice during Depression-era Army Air Corps austerity, but it would be during the global crisis of [[World War II]] that the practice of naming aircraft flourished, with some merely christened, others artistically adorned with cartoons and pin-ups. Puns and references to popular culture were common subjects.<ref name="parentseyes"/> |

||

<!--deleted image [[Image:SPAD SXIII lafayette.jpg|thumb|left|150px|SPAD S.XIII of [[Lafayette Escadrille]]]]--> |

<!--deleted image [[Image:SPAD SXIII lafayette.jpg|thumb|left|150px|SPAD S.XIII of [[Lafayette Escadrille]]]]--> |

||

| Line 29: | Line 29: | ||

Nose art is largely a military tradition, but airliners operated by the airlines of [[Virgin Group]] feature "Virgin Girls" on the nose as part of their livery, and in a broad sense, the tail art of some companies, such as [[Alaska Airlines]], can be called "nose art", also (in the same way as Navy fighters). |

Nose art is largely a military tradition, but airliners operated by the airlines of [[Virgin Group]] feature "Virgin Girls" on the nose as part of their livery, and in a broad sense, the tail art of some companies, such as [[Alaska Airlines]], can be called "nose art", also (in the same way as Navy fighters). |

||

Because of its individual, unofficial nature, it is considered [[folk art]], inseparable from work as well as representative of a group.<ref>Griffith</ref> It can also be compared to sophisticated [[graffiti]]. In both cases, the artist, by and large, is [[anonymous]], and the art itself is [[ephemeral]]. In addition, it relies on materials immediately available.<ref |

Because of its individual, unofficial nature, it is considered [[folk art]], inseparable from work as well as representative of a group.<ref>Griffith</ref> It can also be compared to sophisticated [[graffiti]]. In both cases, the artist, by and large, is [[anonymous]], and the art itself is [[ephemeral]]. In addition, it relies on materials immediately available.<ref name="parentseyes"/> |

||

In a few cases, the artist has been identified. [[Tony Starcer]] was the resident artist for the 91st Bomb Group (Heavy), one of the initial six groups fielded by the [[Eighth Air Force]]. Starcer painted over a hundred pieces of renowned B-17 nose art, including ''Memphis Belle''.{{Fact|date=November 2007}} A commercial artist named Brinkman, from [[Chicago]], was responsible for the zodiac-themed nose art of the [[B-24|Liberator]]-equipped 834th Bomb Squadron.<ref |

In a few cases, the artist has been identified. [[Tony Starcer]] was the resident artist for the 91st Bomb Group (Heavy), one of the initial six groups fielded by the [[Eighth Air Force]]. Starcer painted over a hundred pieces of renowned B-17 nose art, including ''Memphis Belle''.{{Fact|date=November 2007}} A commercial artist named Brinkman, from [[Chicago]], was responsible for the zodiac-themed nose art of the [[B-24|Liberator]]-equipped 834th Bomb Squadron.<ref |

||

| Line 37: | Line 37: | ||

==Purpose== |

==Purpose== |

||

While begun for practical reasons of identifying friend from foe, the practice evolved, with benefits to [[morale]], in expressing pride, relieving the uniform anonymity of the military, offering comfort by recalling home or peacetime life, and as a kind of [[Fetishism|fetish]] against enemy action. The appeal, in part, came from nose art not being officially approved, even when the regulations were not rigorously enforced (or at all).<ref |

While begun for practical reasons of identifying friend from foe, the practice evolved, with benefits to [[morale]], in expressing pride, relieving the uniform anonymity of the military, offering comfort by recalling home or peacetime life, and as a kind of [[Fetishism|fetish]] against enemy action. The appeal, in part, came from nose art not being officially approved, even when the regulations were not rigorously enforced (or at all).<ref name="parentseyes"/><ref>Ethell, p.14</ref> |

||

[[Image:34bg-b24.jpg|thumb|B-24H-15-DT, "Near Sighted Robin", 41-28851 of the [[34th Bomb Group]], Martlesham Heath. Interned in Sweden, 24 August 1944.]] |

[[Image:34bg-b24.jpg|thumb|B-24H-15-DT, "Near Sighted Robin", 41-28851 of the [[34th Bomb Group]], Martlesham Heath. Interned in Sweden, 24 August 1944.]] |

||

==Subject matter== |

==Subject matter== |

||

Source material was widely varied, from [[pinup]]s (such as [[Rita Hayworth]] and [[Betty Grable]]) and fashion to patriotism ([[Yankee Doodle]]) and fictional heroes ([[Sam Spade]]) to lucky symbols ([[dice]] or [[playing cards|cards]]) and [[cartoon]]s to the inevitable ([[Death (personification)|Death]] or the [[Grim Reaper]]),<ref |

Source material was widely varied, from [[pinup]]s (such as [[Rita Hayworth]] and [[Betty Grable]]) and fashion to patriotism ([[Yankee Doodle]]) and fictional heroes ([[Sam Spade]]) to lucky symbols ([[dice]] or [[playing cards|cards]]) and [[cartoon]]s to the inevitable ([[Death (personification)|Death]] or the [[Grim Reaper]]),<ref name="parentseyes"/> with the toons and pin-ups being most popular (among American artists, at least). Other popular topics included animals, nicknames, hometowns, and popular song and movie titles. The ''Luftwaffe'' did not use much nose art, but [[Mickey Mouse]] adorned a [[Condor Legion]] Bf-109 during the Spanish Civil War and one Ju-87A was decorated with a large pig inside a white circle during the same period. [[Adolph Galland]]'s Bf-109E-3 of JG 26 also wore Mickey Mouse in mid-1941. A Ju-87B-1 (S2+AC) of Stab II/St.G 77, piloted by Major [[Alfons Orthofer]] and based in [[Wrocław|Breslau]]-[[Schongarten]] during the [[Invasion of Poland (1939)|Polish September Campaign]] of 1939, was painted with a shark's mouth, and some Bf-110s were decorated with furious wolf's heads or shark mouths on engine covers. Another example was [[Erich Hartmann]]'s Bf-109G-14, "Lumpi", with an eagle's head. A Bf-109g-10 (10 red) of I./[[JG 300]], managed by Officer [[Wolfgang Hunsdorfer]], was flown by various pilots. There is also a spurious squadron, created by ''Luftwaffe'' propaganda, the [[JG 54|''Grünherz'']] (Green Hearts). The [[Soviet Air Force]] decorated their planes with imagery of history, mythical beasts, and patriotic motifs. |

||

The farther the planes and crew were from headquarters or from the public eye, the racier the art tended to be.<ref>[http://parentseyes.arizona.edu/militarynoseart/overview3.htm Military Aircraft Nose Art: An American Tradition] article at "Through Our Parents' Eyes" web site</ref> For instance, nudity was more prevalent with aircraft based in the [[Oceania|South Pacific]] than in England. <ref>[http://www.library.arizona.edu/noseart/ww2-3.htm Nose art article] at University of Arizona web site</ref> |

The farther the planes and crew were from headquarters or from the public eye, the racier the art tended to be.<ref name="parentseyes">[http://parentseyes.arizona.edu/militarynoseart/overview3.htm Military Aircraft Nose Art: An American Tradition] article at "Through Our Parents' Eyes" web site</ref> For instance, nudity was more prevalent with aircraft based in the [[Oceania|South Pacific]] than in England. <ref>[http://www.library.arizona.edu/noseart/ww2-3.htm Nose art article] at University of Arizona web site</ref> |

||

==Famous examples== |

==Famous examples== |

||

| Line 104: | Line 104: | ||

</gallery> |

</gallery> |

||

The largest collection of World War II nose art may be found at the [[Confederate Air Force]] Museum in [[Harlingen, Texas|Harlingen]], [[Texas]].<ref |

The largest collection of World War II nose art may be found at the [[Confederate Air Force]] Museum in [[Harlingen, Texas|Harlingen]], [[Texas]].<ref name="parentseyes"/> |

||

==References== |

==References== |

||

Revision as of 11:29, 19 May 2008

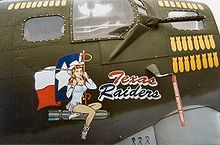

Nose art is a painting or design done on the fuselage near the nose of a warplane, usually for decorative purposes. Nose art is a form of aircraft graffiti.

History

The practice of putting personalized decorations on fighting aircraft originated with Italian and German pilots. The first recorded piece of nose art was a sea monster painted on the nose of an Italian flying boat in 1913. This was followed by the popular tradition of painting mouths underneath the propeller spinner, initiated by the German pilots in World War I, and exemplified by the cavallino of Francesco Baracca. After these beginnings, though, most nose art was conceived and produced by the aircraft ground crews, not the pilots.

Some World War I examples became famous, including the "Hat in the Ring" of the USAAF 94h Aero Squadron (attributed to Lt. Johnny Wentworth)[1] or the "Kicking Mule" of the 95th Aero Squadron. This followed the official policy, established by the AEF's Chief of the Air Service, Brigadier Benjamin Foulois, on 6 May 1918, insisting units have their own distinct, readily identifiable insigne.[2] Nose art was not common practice during Depression-era Army Air Corps austerity, but it would be during the global crisis of World War II that the practice of naming aircraft flourished, with some merely christened, others artistically adorned with cartoons and pin-ups. Puns and references to popular culture were common subjects.[3]

While the nose art in World War I were mainly embellished or extravagant squadron insignia, true nose art started to occur in World War II, which is considered the golden age of nose art by many observers, with both Axis and Allied pilots taking part. At the height of the war, nose-artists were in very high demand in the Army Air Force and were paid quite well for their services while AAF officials tolerated the nose art in an effort to boost the morale of the crew. The U.S. Navy, by contrast, prohibited nose art. In RAF or RCAF service, in addition, nose art seems not to have been commonplace.

The work was done by professional civilian artists as well as talented amateur servicemen. In 1941, for instance, 39th Pursuit Squadron had a Bell Aircraft artist design and paint an attractive "Cobra in the Clouds" logo.[4] Early in 1943, as the 39th distinguished itself in becoming the first American squadron in their theatre with 100 kills, unit pride and esprit de corps led to the adoption of a "shark's teeth" motif for their P-38s.[5]

Lack of restraint, combined with the stresses of war and high probability of death, resulted in a volume and excellence of nose art yet to be repeated.

In the Korean War, nose art was popular with units operating A-26 and B-29 bombers, and C-119 Flying Boxcar transports, as well as USAF fighter-bombers.[6] Due to changes in military policies and changing attitudes toward representation of women, the amount of nose art has been in steady decline since the Korean War. Nose art underwent a revival, however, during Operation Desert Storm and has been going strong since Operation Enduring Freedom and Operation Iraqi Freedom. The United States Air Force had unofficially sanctioned the return of the pin-up, albeit fully clothed, with Strategic Air Command permitting nose art on its bomber force in the Command's last years. The continuation of historic names such as Memphis Belle was traditional, also. Special Operations Squadrons routinely named AC-130 gunships, usually with names of vengeance ("Thor", "Azrael - Angel of Death"). The flying skeleton with a Minigun logo, applied to many aircraft, was the unofficial gunship badge until after the conclusion of the war in Southeast Asia, and was later adopted officially.

Nose art is largely a military tradition, but airliners operated by the airlines of Virgin Group feature "Virgin Girls" on the nose as part of their livery, and in a broad sense, the tail art of some companies, such as Alaska Airlines, can be called "nose art", also (in the same way as Navy fighters).

Because of its individual, unofficial nature, it is considered folk art, inseparable from work as well as representative of a group.[7] It can also be compared to sophisticated graffiti. In both cases, the artist, by and large, is anonymous, and the art itself is ephemeral. In addition, it relies on materials immediately available.[3]

In a few cases, the artist has been identified. Tony Starcer was the resident artist for the 91st Bomb Group (Heavy), one of the initial six groups fielded by the Eighth Air Force. Starcer painted over a hundred pieces of renowned B-17 nose art, including Memphis Belle.[citation needed] A commercial artist named Brinkman, from Chicago, was responsible for the zodiac-themed nose art of the Liberator-equipped 834th Bomb Squadron.[8]

Formula One constructor Jordan also added nose art to their cars.

Purpose

While begun for practical reasons of identifying friend from foe, the practice evolved, with benefits to morale, in expressing pride, relieving the uniform anonymity of the military, offering comfort by recalling home or peacetime life, and as a kind of fetish against enemy action. The appeal, in part, came from nose art not being officially approved, even when the regulations were not rigorously enforced (or at all).[3][9]

Subject matter

Source material was widely varied, from pinups (such as Rita Hayworth and Betty Grable) and fashion to patriotism (Yankee Doodle) and fictional heroes (Sam Spade) to lucky symbols (dice or cards) and cartoons to the inevitable (Death or the Grim Reaper),[3] with the toons and pin-ups being most popular (among American artists, at least). Other popular topics included animals, nicknames, hometowns, and popular song and movie titles. The Luftwaffe did not use much nose art, but Mickey Mouse adorned a Condor Legion Bf-109 during the Spanish Civil War and one Ju-87A was decorated with a large pig inside a white circle during the same period. Adolph Galland's Bf-109E-3 of JG 26 also wore Mickey Mouse in mid-1941. A Ju-87B-1 (S2+AC) of Stab II/St.G 77, piloted by Major Alfons Orthofer and based in Breslau-Schongarten during the Polish September Campaign of 1939, was painted with a shark's mouth, and some Bf-110s were decorated with furious wolf's heads or shark mouths on engine covers. Another example was Erich Hartmann's Bf-109G-14, "Lumpi", with an eagle's head. A Bf-109g-10 (10 red) of I./JG 300, managed by Officer Wolfgang Hunsdorfer, was flown by various pilots. There is also a spurious squadron, created by Luftwaffe propaganda, the Grünherz (Green Hearts). The Soviet Air Force decorated their planes with imagery of history, mythical beasts, and patriotic motifs.

The farther the planes and crew were from headquarters or from the public eye, the racier the art tended to be.[3] For instance, nudity was more prevalent with aircraft based in the South Pacific than in England. [10]

Famous examples

The shark's teeth, commonly attributed to the AVG, were actually introduced by 112 (Kittyhawk) Squadron, RAF, in the desert during 1942.[11]

Oberstleutnant Werner Mölders flew a yellow-nosed Bf-109F2 while with JG 51 during June 1941.

Photos

-

Cowl art on Dr.I reproduction at National Museum of the United States Air Force, based on that on Werner Voss' own Dr.I

-

Albatros D.III

-

SPAD S.XIII of , marked as Eddie Rickenbacker's aircraft of the 94th Aero Squadron, shown here on the flightline at Wright-Patterson AFB where it is part of the collection of the National Museum of the United States Air Force.

-

Seversky P-35 in the colors of the 17th Pursuit Squadron

-

B-17 "Liberty Belle"

-

Bf-109E at Deutsches Museum

-

P-39Q

-

Bf-109F4/trop of Hauptmann Hans-Joachim Marseille, 3./JG 27, September 1942

-

North American B-25 Mitchell at Niederrhein Airport

-

B-25J "Super Rabbit" at Evergreen Museum

-

B-25J "Briefing Time"

-

B-25J-35

-

"Miss Patricia", September 1943

-

P-51 "Cincinnati Miss"

-

P-51 in Korea

-

P-51 "Big Beautiful Doll" in Imperial War Museum

-

"Bock's Car" profile

-

B-29 "Command Decision"

-

B-29 "Fertile Myrtle" carrying X-1

-

Captain Charles E. Yeager with X-1 "Glamorous Glennis"

-

Joe Walker with X-1E "Little Joe"

-

F-86 inspired by Glenn's

-

Boeing CH-47 Chinook from Company F, "River City Hookers", 106th Aviation, Iowa Army National Guard during Operation Iraqi Freedom

-

F-14 of VF-213 "Black Lions"

-

F-14 of VF-101 "Grim Reapers"

-

Tomcatter aboard Vinson

-

VMFA(AW)-332 "Moonlighters"

-

Don Gentile’s “Shangri-La” of the 4th Fighter Group

The largest collection of World War II nose art may be found at the Confederate Air Force Museum in Harlingen, Texas.[3]

References

- ^ Air Force Historical Research Agency

- ^ Air Force Historical Research Agency

- ^ a b c d e f Military Aircraft Nose Art: An American Tradition article at "Through Our Parents' Eyes" web site

- ^ HistorySummary

- ^ HistorySummary

- ^ Thompson, Warren E., Heavy Hauler, "Wings of Fame, Volume 20". London, United Kingdom: Aerospace Publishing Ltd., 2000. ISBN 1-86184-053-5. page 107.

- ^ Griffith

- ^ Valant, Gary M. Classic Vintage Nose Art. Ann Arbor, Michigan: Lowe and B. Hould, an imprint of Borders, Inc., 1997. ISBN 0-681-22744-3. pages 13-15.

- ^ Ethell, p.14

- ^ Nose art article at University of Arizona web site

- ^ McDowell, p.8-9

- Velasco, Gary Velasco, FIGHTING COLORS The Creation of Military Aircraft Nose Art. Turner Publishing, 2004

- Campbell, John M. & Donna, War Paint. Shrewsbury, 1990

- Chinnery, Philip, Desert Boneyard: Davis Monthan A.F.B. Arizona. Osceola, Wisconsin: Motorbooks, International, 1987.

- Cohan, Phil, "Risque Business." Air and Space 5 (Apr.-May 1990):62-71.

- Davis, Larry, Planes, Names and Dames: 1940-1945. Vol. 1. Carrollton, Texas: Squadron/Signal Publications, 1990.

- Davis, Larry, Planes, Names and Dames: 1946-1960. Vol. 2. Carrollton, Texas: Squadron/Signal Publications, 1990.

- Davis, Larry, Planes, Names and Dames: 1955-1975. Vol. 3. Carrollton, Texas: Squadron/Signal Publications, 1990.

- Dorr, Robert F., Fighting Colors: Glory Days of U.S. Aircraft Markings. Osceola, Wisconsin: Motorbooks International, 1990.

- Ethell, Jeffrey L., The History of Aircraft Nose Art: World War I to Today. Osceola, Wisconsin: Motorbooks International, 1991.

- Fugere, Jerry, Desert Storm B-52 Nose Art. Tucson, AZ: J. Fugere, 1999.

- Logan, Ian, Classy Chassy. New York: W. W. Visual Library, 1977.

- March, Peter R., Desert Warpaint. London: Osprey Aerospace, 1992.

- McDowell, Ernest R., The P-40 Kittyhawk at War. New York: Arco Publishing, 1968.

- O'Leary, Michael D., "Disney Goes to War!" Air Classics 32, no. 5 (1996): 40-42, 45-51.

- Valant, Gary M., Vintage Aircraft Nose Art. Osceola, Wisconsin: Motorbooks International, 1987.

- Walker, Randy, Painted Ladies. West Chester, Pennsylvania: Schiffer Publishing, 1992.

- Walker, Randy, More Painted Ladies. Atglen, Pennsylvania: Schiffer Publishing, 1994.