Jean-Jacques Rousseau: Difference between revisions

| [pending revision] | [pending revision] |

No edit summary |

Fix markup |

||

| Line 97: | Line 97: | ||

Rousseau's detractors have blamed him for everything they do not like in what they call modern "child-centered" education. John Darling's 1994 book ''Child-Centered Education and its Critics'' argues that the history of modern [[pedagogy|educational theory]] is a series of footnotes to Rousseau. However, educators such as Rousseau's near contemporary [[Pestalozzi]], [[Mme Genliss]], [[Maria Montessori]] and [[Dewey]] have arguably had more influence in the development modern educational reforms. |

Rousseau's detractors have blamed him for everything they do not like in what they call modern "child-centered" education. John Darling's 1994 book ''Child-Centered Education and its Critics'' argues that the history of modern [[pedagogy|educational theory]] is a series of footnotes to Rousseau. However, educators such as Rousseau's near contemporary [[Pestalozzi]], [[Mme Genliss]], [[Maria Montessori]] and [[Dewey]] have arguably had more influence in the development modern educational reforms. |

||

==Religion |

==Religion== |

||

Although (unlike many of the more radical Enlightenment philosopher), Rousseau believed in God and affirmed the necessity of religion, he repudiated the doctrine of [[original sin]], which plays so large a part in [[Calvinism]]. (in ''Emile'', Rousseau writes ''there is no original perversity in the human heart''<ref> ''il n’y a point de perversité originelle dans le cœur humain'' http://fr.wikisource.org/wiki/Émile,_ou_De_l’éducation_-_Livre_second</ref>), and his endorsement of religious toleration [[indifferentism]] as expounded by the Savoyard Vicar in ''Émile'' led to the condemnation of the book in both [[Calvinist]] [[Geneva]] and [[Roman Catholic Church|Catholic]] Paris. His assertion in the ''[[Social Contract (Rousseau)|Social Contract]]'' that true followers of [[Jesus]] would not make good citizens may have been another reason for Rousseau's condemnation in Geneva. Rousseau attempted to defend himself against critics of his religious views in his Letter to [[Christophe de Beaumont]], the Archbishop of Paris.<ref>The full text of the letter is available online only in the French original: [http://alain-leger.mageos.com/docs/Rousseau.pdf Lettre à Mgr De Beaumont Archevêque de Paris (1762)]</ref> |

Although (unlike many of the more radical Enlightenment philosopher), Rousseau believed in God and affirmed the necessity of religion, he repudiated the doctrine of [[original sin]], which plays so large a part in [[Calvinism]]. (in ''Emile'', Rousseau writes ''there is no original perversity in the human heart''<ref> ''il n’y a point de perversité originelle dans le cœur humain'' http://fr.wikisource.org/wiki/Émile,_ou_De_l’éducation_-_Livre_second</ref>), and his endorsement of religious toleration [[indifferentism]] as expounded by the Savoyard Vicar in ''Émile'' led to the condemnation of the book in both [[Calvinist]] [[Geneva]] and [[Roman Catholic Church|Catholic]] Paris. His assertion in the ''[[Social Contract (Rousseau)|Social Contract]]'' that true followers of [[Jesus]] would not make good citizens may have been another reason for Rousseau's condemnation in Geneva. Rousseau attempted to defend himself against critics of his religious views in his Letter to [[Christophe de Beaumont]], the Archbishop of Paris.<ref>The full text of the letter is available online only in the French original: [http://alain-leger.mageos.com/docs/Rousseau.pdf Lettre à Mgr De Beaumont Archevêque de Paris (1762)]</ref> |

||

Revision as of 22:37, 3 February 2009

Jean-Jacques Rousseau | |

|---|---|

| Era | 18th-century philosophy (Modern Philosophy) |

| Region | Western Philosophers |

| School | Social contract theory, Enlightenment |

Main interests | Political philosophy,music, education, literature, autobiography |

Notable ideas | General will, amour-propre, moral simplicity of humanity |

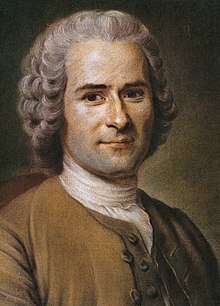

Jean Jacques Rousseau (Geneva, 1712 – Ermenonville, 2 July 1778) was a major philosopher, writer, and composer of the eighteenth century Enlightenment, whose political philosophy influenced the French Revolution and the development of modern political and educational thought. His novel, Emile: or, On Education, which he considered his most important work, is a seminal treatise on the education of the whole person for citizenship. His Sentimental Novel, Julie, ou la nouvelle Héloïse, was of great importance to the development of pre-Romanticism [1] and romanticism in fiction .[2] Rousseau's autobiographical writings: his Confessions, which initiated the modern autobiography, and his Reveries of a Solitary Walker (along with the works of Lessing and Goethe in Germany, and Richardson and Sterne in England), were among the pre-eminent examples of the late eighteenth century movement known as the "Age of Sensibility", featuring an increasing focus on subjectivity and introspection that has characterized the modern age. Rousseau also wrote a play and two operas, and made important contributions to music as a theorist. He was interred as a national hero in the Panthéon in Paris, in 1794, sixteen years after his death,

Biography

Rousseau was born on June 27, 1712 in Geneva, an associated member of the Old Confederation (known today as the Helvetian Confederation of Switzerland). Rousseau, who was proud that his family had voting rights in that city, throughout his life described himself as a citizen of the Genevan Republic. Nine days after his birth, his mother, Suzanne Bernard Rousseau, died of birth complications. Rousseau's father, a watchmaker, taught him to read at the age of five or six:

Every night, after supper, we read some part of a small collection of romances [i.e., adventure stories], which had been my mother's. My father's design was only to improve me in reading, and he thought these entertaining works were calculated to give me a fondness for it; but we soon found ourselves so interested in the adventures they contained, that we alternately read whole nights together, and could not bear to give over until at the conclusion of a volume. Sometimes, in a morning, on hearing the swallows at our window, my father, quite ashamed of this weakness, would cry, "Come, come, let us go to bed; I am more a child than thou art."--Confessions, Book 1

Not long afterwards, Rousseau abandoned his taste for chivalric adventure stories for the antiquity of Plutarch's Lives of the Noble Greeks and Romans, which became the constant companion of his childish imagination.

When he was ten years old, Rousseau's father got in a quarrel with a French captain, and fled the city to avoid imprisonment leaving Rousseau with an uncle and young cousin. Here Rousseau picked up the elements of mathematics and drawings.

All our information about Rousseau's youth comes from his posthumously published Confessions, in which the chronology is somewhat confusing. After several years of apprenticeship to a notary and then an engraver, Rousseau left Geneva at age 16 on March 14, 1728. He supported himself for a time as a servant and wandered in Italy (Piedmont and Savoy) and France. He then met a French baroness named Françoise-Louise de Warens, who was ostensibly a Catholic convert from Protestantism, but actually more of a Deist in her views. De Warens, who was thirteen years his senior, employed Rousseau as a secretary and teacher. Partly through her influence he converted to Catholicism, which resulted in his having to give up his Geneva citizenship, although he would later revert back to Calvinism in order to regain it. Mme de Warens also sent Rousseau to a Catholic school, which provided him with an excellent classical education that included the study of Aristotle, ancient Roman literature, and the dramatic arts. She also paid for him to formally study music, in which he was passionately interested.

In order to present the Académie des Sciences with a new system of numbered musical notation, Rousseau moved to Paris in 1742. His system is based on a single line displaying numbers representing intervals between notes and dots and commas indicating rhythmic values. The system was intended to be compatible with typography. Believing the system was impractical and unoriginal, the Academy rejected it. However, in some parts of the world[citation needed], a version of the system remains in use.

From 1743 to 44 Rousseau had an honorable but ill-paying post as a secretary to the French ambassador in Venice, to whose republican form of government Rousseau often referred in his later political works. Venice also awoke in him a life-long love for Italian music, particularly opera:

I had brought with me from Paris the prejudice of that city against Italian music; but I had also received from nature a sensibility and niceness of distinction which prejudice cannot withstand. I soon contracted that passion for Italian music with which it inspires all those who are capable of feeling its excellence. In listening to barcaroles, I found I had not yet known what singing was... --Confessions

After eleven months, however, Rousseau quarreled with his employer, was dismissed, and fled to Paris to avoid prosecution for debt. In Paris, the penniless Rousseau befriended and lived with Thérèse Levasseur, a semi-literate seamstress and her termagant mother. According to Rousseau, Thérèse allegedly bore him as many as five children. Rousseau later wrote that he persuaded Thérèse to give each of the newborns up to a foundling hospital, for the sake of her "honor." As the mortality rate for orphanage children was very high, most of them would have likely have perished. When Rousseau subsequently became celebrated as a theorist of education and child-rearing, his abandonment of his children was used by his critics, including Voltaire, to attack him.

While in Paris, Rousseau became friends with French philosopher Diderot and, beginning with some articles on music in 1749,[3] he contributed several articles to Diderot and D'Alambert's great Encyclopédie, the most famous of which was an article on political economy written in 1755.

In 1749 Rousseau visited Diderot, who had been thrown into prison in Vincennes for some opinions in his "Lettre sur les aveugles," that appeared to threaten revealed religion. Rousseau had read about an essay competition sponsored by the Académie de Dijon, to be published in the Mercure de France. The theme of the essay was the question whether the development of the arts and sciences had been morally beneficial. Rousseau had originally intended to answer this in the conventional way, but Diderot may have convinced him to propose the paradoxical negative answer that catapulted him into the public eye. Rousseau's 1750 "Discourse on the Arts and Sciences" was awarded the first prize and gained him significant fame.

Rousseau continued his interest in music, and his opera Le Devin du Village was performed for King Louis XV in 1752. The same year, the visit of a troupe of Italian musicians to Paris, and their performance of Giovanni Battista Pergolesi's La Serva Padrona, prompted the Querelle des Bouffons, which pitted protagonists of French music against supporters of the Italian style. Rousseau as noted above, was an enthusiastic supporter of the Italians against Jean-Philippe Rameau and others, making an important contribution with his Letter on French Music.

On returning to Geneva in 1754, Rousseau reconverted to Calvinism and regained his official Genevan citizenship. In 1755, Rousseau completed his second major work, the Discourse on the Origin and Basis of Inequality Among Men (the Discourse on Inequality).

He also pursued an important but unconsummated romantic attachment with Sophie d'Houdetot, which partly inspired his highly successful novel of sentiment, Julie, ou la nouvelle Héloïse, published in 1761. Shortly thereafter, Rousseau became involved in a bitter three-way quarrel with his former friends, Diderot and the philologist Grimm, and his patroness Madame d'Epinay. Diderot later described Rousseau as being,"deceitful, vain as Satan, ungrateful, cruel, hypocritical, and full of malice." Following this break with the Encyclopedists, Rousseau enjoyed the support and patronage of the Duc de Luxembourg, one of the wealthiest nobles in France.

In 1762, Rousseau published two major books, Du Contrat Social, Principes du droit politique (in English, literally Of the Social Contract, Principles of Political Right) in April and then Émile, or On Education in May. One section of Émile, "The Confessions of Savoyard Vicar," advocated the opinion that insofar as they lead people to virtue, all religions are equally worthy and that people should therefore conform to the one in which they had been brought up. This religious indifferentism caused Rousseau and his books to be banned from France and Geneva. British philosopher David Hume, a sympathetic observer, "professed no surprise when he learned that Rousseau's books were banned in Geneva and elsewhere [and he was threatened with imprisonment]. Rousseau, he wrote, 'has not had the precaution to throw any veil over his sentiments; and, as he scorns to dissemble his contempt for established opinions, he could not wonder that all the zealots were in arms against him. The liberty of the press is not so secured in any country … as not to render such an open attack on popular prejudice somewhat dangerous.'"[4] Forced to flee arrest, Rousseau made stops in Bern and Môtiers in Switzerland, where he enjoyed the protection of Frederick the Great of Prussia and his local representative, Lord Keith. While in Môtiers, Rousseau wrote the Constitutional Project for Corsica (Projet de Constitution pour la Corse).

After his house in Motiers was stoned on the night of 6 September 1765– he took refuge with David Hume Great Britain. Isolated at Wootton on the borders of Derbyshire and Staffordshire, Rousseau, never emotionally stable, suffered a serious decline in his mental health and began to experience paranoid fantasies about plots against him involving Hume and others. Rousseau's letter to Hume, in which he articulates the perceived misconduct, sparked an exchange which was published in and received with great interest in contemporary Paris.

Although, he was not supposed to return to France before 1770, Rousseau did come back in 1767 under the name "Renou". In 1768 he went through a formal marriage of sorts to Thérèse, and in 1770 he returned to Paris. As a condition of his return, he was not allowed to publish any books, but after completing his Confessions, Rousseau began private readings in 1771. At the request of Madame d'Epinay, however, the police ordered him to stop, and the Confessions was only partially published in 1782, four years after his death. All his subsequent works were only to appear posthumously.

In 1772, he was invited to present recommendations for a new constitution for the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, resulting in the Considerations on the Government of Poland, which was to be his last major political work. In 1776 he completed Dialogues: Rousseau Judge of Jean-Jacques and began work on the Reveries of the Solitary Walker. In order to support himself, he returned to copying music. Rousseau's final years were largely spent in deliberate withdrawal; however, he did respond favourably to an approach from the composer Gluck, whom he met in 1774. One of Rousseau's last pieces of writing was a critical yet enthusiastic analysis of Gluck's opera Alceste. While taking a morning walk on the estate of the Marquis de Giradin at Ermenonville (28 miles northeast of Paris), Rousseau suffered a hemorrhage and died on 2 July 1778.

Rousseau was initially buried on the Ile des Peupliers. His remains were moved to the Panthéon in Paris in 1794, sixteen years after his death, where they are located directly across from those of his contemporary Voltaire. The tomb was designed to resemble a rustic classical temple, to evoke Rousseau's deep love of nature and antiquity. In 1834, the Genevan government reluctantly erected a statue in his honour on the tiny Île Rousseau in Lake Geneva. In 2002, the Espace Rousseau was established at 40 Grand-Rue, Geneva, Rousseau's birthplace.

Philosophy

Theory of Natural Man

The first man who, having fenced in a piece of land, said "This is mine," and found people naive enough to believe him, that man was the true founder of civil society. From how many crimes, wars, and murders, from how many horrors and misfortunes might not any one have saved mankind, by pulling up the stakes, or filling up the ditch, and crying to his fellows: Beware of listening to this impostor; you are undone if you once forget that the fruits of the earth belong to us all, and the earth itself to nobody.

— Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Discourse on Inequality, 1754

Rousseau saw a fundamental divide between society and human nature. Rousseau believed that man was innocent when he was in a state of nature (the state of all other animals, and the condition of humanity before the creation of civilization and society), but is corrupted by the development of society. This has led Anglophone critics to erroneously attribute to Rousseau the invention of idea of the noble savage, an oxymoronic expression that was never used in France and which grossly misrepresents Rousseau's thought.[5] (The expression, "the noble savage" was first used in 1672 by poet John Dryden in his play The Conquest of Granada).

Rousseau's idea of natural goodness is complex. Contrary to what his many detractors have claimed on the basis of casual readings, Rousseau never suggests that humans in the state of nature act morally; in fact, terms such as 'justice' or 'wickedness' are inapplicable to pre-political society as Rousseau understands it. Humans "in a state of Nature" may act with all of the ferocity of an animal. They are merely good insofar as they are self-sufficient and thus not subject to the vices of political society. In fact, Rousseau's natural man is virtually identical to a solitary chimpanzee or other ape, and the the "natural" goodness of humanity is thus the goodness of an animal. Rousseau, an ostensible deteriorationist, proposed that that, except perhaps for brief moments of balance, at or near its inception, human culture has always been artificial, creating inequality, envy, and unnatural desires.

In contrast to many of his Enlightenment contemporaries who praised the seemingly endless benefits of modern science and material progress, Rousseau, a writer of stylistic genius who stated his case strikingly for maximum effect, held that so-called progress -- the development of complex civilizations, has been inimical to the well-being of humanity, unless counteracted by the cultivation of civic morality and duty, which can only be inculcated by education. He writes in The Social Contract:

The passage from the state of nature to the civil state produces a very remarkable change in man, by substituting justice for instinct in his conduct, and giving his actions the morality they had formerly lacked. Then only, when the voice of duty takes the place of physical impulses and right of appetite, does man, who so far had considered only himself, find that he is forced to act on different principles, and to consult his reason before listening to his inclinations. Although, in this state, he deprives himself of some advantages which he got from nature, he gains in return others so great, his faculties are so stimulated and developed, his ideas so extended, his feelings so ennobled, and his whole soul so uplifted, that, did not the abuses of this new condition often degrade him below that which he left, he would be bound to bless continually the happy moment which took him from it for ever, and, instead of a stupid and unimaginative animal, made him an intelligent being and a man.

[6]. The society corrupts the Man only because the Social Contract does not succeed, de facto. The Society doesn't corrupt the Man per se, only if the society failed and the society actually failed as we see it in the Discourse on Inequality. There is no contradiction in Rousseau's thought but rather a strong unity.

In Rousseau's philosophy, society's negative influence on men centers on its transformation of amour de soi, a positive self-love, into amour-propre, or pride. Amour de soi represents the instinctive human desire for self-preservation, combined with the human power of reason. In contrast, amour-propre is artificial and encourages man to compare himself to others, thus creating unwarranted fear and allowing men to take pleasure in the pain or weakness of others. Rousseau was not the first to make this distinction; it had been invoked by, among others, Vauvenargues.

In "Discourse on the Arts and Sciences" Rousseau argued that the arts and sciences had not been beneficial to humankind because they were not human needs, but rather a result of pride and vanity. Moreover, the opportunities they created for idleness and luxury contributed to the corruption of man. He proposed that the progress of knowledge had made governments more powerful and had crushed individual liberty. He concluded that material progress had actually undermined the possibility of true friendship by replacing it with jealousy, fear and suspicion.

His subsequent Discourse on Inequality tracked the progress and degeneration of mankind from a primitive state of nature to modern society. He suggested that the earliest human beings were solitary and differentiated from animals by their capacity for free will and their perfectibility. He also argued that these primitive humans were possessed of a basic drive to care for themselves and a natural disposition to compassion or pity. As humans were forced to associate together more closely by the pressure of population growth, they underwent a psychological transformation and came to value the good opinion of others as an essential component of their own well-being. Rousseau associated this new self-awareness with a golden age of human flourishing. However, the development of agriculture, metallurgy, private property, and the division of labour led to humans becoming increasingly dependent on one another, and led to economic inequality. The resulting state of conflict led Rousseau to suggest that the first state was invented as a kind of social contract made at the suggestion of the rich and powerful. This original contract was deeply flawed as the wealthiest and most powerful members of society tricked the general population, and thus instituted inequality as a fundamental feature of human society. Rousseau's own conception of the social contract can be understood as an alternative to this fraudulent form of association. At the end of the Discourse on Inequality, Rousseau explains how the desire to have value in the eyes of others, which originated in the golden age, comes to undermine personal integrity and authenticity in a society marked by interdependence, hierarchy, and inequality.

Political theory

Perhaps Jean-Jacques Rousseau's most important work is The Social Contract, which outlines the basis for a legitimate political order within a framework of classical republicanism. Published in 1762, it became one of the most influential works of political philosophy in the Western tradition. It developed some of the ideas mentioned in an earlier work, the article Economie Politique, featured in Diderot's Encyclopédie. The treatise begins with the dramatic opening lines, "Man is born free, and everywhere he is in chains. One man thinks himself the master of others, but remains more of a slave than they." Rousseau claimed that the state of nature was a primitive condition without law or morality, which human beings left for the benefits and necessity of cooperation. As society developed, division of labour and private property required the human race to adopt institutions of law. In the degenerate phase of society, man is prone to be in frequent competition with his fellow men while at the same time becoming increasingly dependent on them. This double pressure threatens both his survival and his freedom. According to Rousseau, by joining together into civil society through the social contract and abandoning their claims of natural right, individuals can both preserve themselves and remain free. This is because submission to the authority of the general will of the people as a whole guarantees individuals against being subordinated to the wills of others and also ensures that they obey themselves because they are, collectively, the authors of the law.

While Rousseau argues that sovereignty should be in the hands of the people, he also makes a sharp distinction between sovereignty and government. The government is charged with implementing and enforcing the general will and is composed of a smaller group of citizens, known as magistrates. Rousseau was bitterly opposed to the idea that the people should exercise sovereignty via a representative assembly. Rather, they should make the laws directly. It was argued that this would prevent Rousseau's ideal state from being realized in a large society, such as France was at the time. Much of the subsequent controversy about Rousseau's work has hinged on disagreements concerning his claims that citizens constrained to obey the general will are thereby rendered free.

Education

Rousseau set out his views on education in Émile, a fictitious work detailing the ideal education of a young boy of that name. Émile is to be raised in the countryside, to which, Rousseau believes, humans are most naturally suited, rather than in a city, where we only learn bad habits, both physical and intellectual. The aim of education, Rousseau says, is to learn how to live righteously. This is accomplished by following a tutor or guardian who can guide his pupil through various contrived learning experiences.

The growth of a child is divided into three sections, first to the age of about 12, when calculating and complex thinking is not possible, and children, according to his deepest conviction, live like animals. Second, from 12 to about 16, when reason starts to develop, and finally from the age of 16 onwards, when the child develops into an adult. During this stage, the young adult should learn a skill, such as carpentry. This trade is offered because it requires creativity and thought and would not compromise one's morals. It is at this age that Émile finds a young woman to complement him. In thus delineating the different stages of a child's emotional and intellectual growth, Rousseau was one of the first to advocate developmentally appropriate education.

Furthermore, Rousseau’s philosophy of education is not concerned with particular techniques of imparting information and concepts. But rather with develop the pupil’s character and moral sense, so that he may learn to practice self-mastery and remain virtuous even in the unnatural and imperfect society in which he lives.

Rousseau, although advanced by the standard of his time, was still a believer in male dominance and the moral superiority of the patriarchal family. He proposes a different sort of education for Sophie, the young woman Emile is destined to marry. Sophie (as a representative of ideal womanhood) is educated to be governed (by her husband) while Émile (as a representative of the ideal man) is educated to be self-governing. This is not an accidental feature of Rousseau's educational and political philosophy; it is essential to his account of the distinction between private, personal relations and the public world of political relations. The private sphere as Rousseau imagines it depends on the (naturalized) subordination of women in order for both it and the public political sphere (upon which it depends) to function as Rousseau imagines it could and should.

In a letter he wrote to Philibert Cramer (13 October 1764) Rousseau described his intentions in writing Émile. “You say quite correctly that it is impossible to produce an Émile. But I cannot believe that you take the book that carries this name for a true treatise on education. It is rather a philosophical work on the principle advanced by the author in other writings that man is naturally good. To reconcile this principle with the other truth, no less certain, that men are bad, it would be necessary to show in the human heart the history of all the vices . . . . In that sea of passion which submerges us, before one seeks to clear the way one must begin by finding it."

Rousseau's detractors have blamed him for everything they do not like in what they call modern "child-centered" education. John Darling's 1994 book Child-Centered Education and its Critics argues that the history of modern educational theory is a series of footnotes to Rousseau. However, educators such as Rousseau's near contemporary Pestalozzi, Mme Genliss, Maria Montessori and Dewey have arguably had more influence in the development modern educational reforms.

Religion

Although (unlike many of the more radical Enlightenment philosopher), Rousseau believed in God and affirmed the necessity of religion, he repudiated the doctrine of original sin, which plays so large a part in Calvinism. (in Emile, Rousseau writes there is no original perversity in the human heart[7]), and his endorsement of religious toleration indifferentism as expounded by the Savoyard Vicar in Émile led to the condemnation of the book in both Calvinist Geneva and Catholic Paris. His assertion in the Social Contract that true followers of Jesus would not make good citizens may have been another reason for Rousseau's condemnation in Geneva. Rousseau attempted to defend himself against critics of his religious views in his Letter to Christophe de Beaumont, the Archbishop of Paris.[8]

Legacy

At the time of the French Revolution, Rousseau's ideas were influential. Writers such as Benjamin Constant and Burke sought to blame the excesses of the Revolution's Reign of Terror on Rousseau, but since popular sovereignty was exercised through representatives rather than directly, it cannot be said [citation needed] the Revolution was an implementation of Rousseau's ideas, for he did not make any direct quotes. The Declaration of the Rights of Man, a result of the Revolution, has its philosophical foundation in the assumption that humans are born with inherent and inalienable rights, a notion Rousseau rejects [citation needed].

Despite some similarities in thought, there is little evidence that Rousseau had an impact on Thomas Jefferson and, indeed, he seems to have had little impact on 18th century political thought in the United States, which was dominated by Republicanism and Liberalism.[9] These two were actually more influenced by the English Liberal philosopher John Locke. However he did have some indirect influence, through the writings of Wordsworth and Kant, on the New England Transcendentalists Ralph Waldo Emerson, and his disciple Henry David Thoreau, as well as on the Unitarian theologian William Ellery Channing.[10]

See also

- Democracy

- Georges Hébert, a physical culturist influenced by Rousseau's teachings

- List of liberal thinkers

- Political absolutism

- Political radicalism

- Rousseau Institute

- Rousseau's educational philosophy

- Socialism

- Totalitarianism

Notes

- ^ http://www.enotes.com/literary-criticism/preromanticism

- ^ See also Robert Darnton, The Great Cat Massacre, chapter 6: "Readers Respond to Rousseau: The Fabrication of Romantic Sensitivity" for some interesting examples of contemporary reactions to this novel.

- ^ Rousseau in his musical articles in the Encyclopedie engaged in lively controversy with other musicians, e.g. with Rameau, as in his article on Temperament, for which see Encyclopédie: Tempérament (English translation), also Temperament Ordinaire.

- ^ Peter Gay, The Enlightenment, The Science of Freedom, p.72.

- ^ See A. O. Lovejoy's essay on "The Suppposed Primitivism of Rousseau's Rousseau's Discourse on Inequality" in Essays in the History of Ideas (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press, 1948. 1960). See also Ter Ellinson The Myth of the Noble Savage (Berkely, CA: University of California Press, 2001).

- ^ The Social contract Livre I Chapter 8 [1]

- ^ il n’y a point de perversité originelle dans le cœur humain http://fr.wikisource.org/wiki/Émile,_ou_De_l’éducation_-_Livre_second

- ^ The full text of the letter is available online only in the French original: Lettre à Mgr De Beaumont Archevêque de Paris (1762)

- ^ The case for Rousseau as an enemy of the Enlightenment is made in Graeme Garrard, Rousseau's Counter-Enlightenment: A Republican Critique of the Philosophes (Albany: SUNY Press, 2003).

- ^ "Rousseau, whose romantic and egalitarian tenets had practically no influence on the course of Jefferson's, or indeed any American, thought." Nathan Schachner, Thomas Jefferson: A Biography. (1957). p. 47. One admirer was lexicographer Noah Webster. Mark J. Temmer, "Rousseau and Thoreau," Yale French Studies, No. 28, Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1961), pp. 112-121.

References

- Abizadeh, Arash (2001). "Banishing the Particular: Rousseau on Rhetoric, Patrie, and the Passions" Political Theory 29.4: 556-82.

- Bertram, Christopher (2003). Rousseau and The Social Contract. London: Routledge.

- Cassirer Ernst, Rousseau, Kant, Goethe, Princeton University Press, Princeton, 1945.

- Conrad, Felicity (2008). "Rousseau Gets Spanked, or, Chomsky's Revenge." The Journal of POLI 433. 1.1: 1-24.

- Cooper, Laurence (1999).Rousseau, Nature and the Problem of the Good Life. Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State University Press.

- Cottret, Monique, Cottret, Bernard, Jean-Jacques Rousseau en son temps, Paris, Perrin, 2005.

- Cranston, Maurice (1982). Jean-Jacques: The Early Life and Work. New York: Norton.

- Cranston, Maurice (1991). The Noble Savage. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Cranston, Maurice (1997). The Solitary Self. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Damrosch, Leo (2005). Jean-Jacques Rousseau: Restless Genius. New York: Houghton Mifflin.

- Dent, N.J.H. (1988). Rousseau : An Introduction to his Psychological, Social, and Political Theory. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Dent, N.J.H. (1992). A Rousseau Dictionary. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Dent, N.J.H. (2005). Rousseau. London: Routledge.

- Derrida, Jacques (1976). Of Grammatology, trans. Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press.

- Einaudi, Mario. (1968). Early Rousseau. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

- Farrell, John (2006). Paranoia and Modernity: Cervantes to Rousseau. New York: Cornell University Press.

- Garrard, Graeme (2003). Rousseau's Counter-Enlightenment: A Republican Critique of the Philosophes. Albany: State University of New York Press.

- Gauthier, David (2006). Rousseau: The Sentiment of Existence. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- LaFreniere, Gilbert F. (1990) "Rousseau and the European Roots of Environmentalism." Environmental History Review 14 (No. 4): 41-72

- Lange, Lynda (2002). Feminist Interpretations of Jean-Jacques Rousseau. University Park: Penn State University Press.

- Marks, Jonathan (2005). Perfection and Disharmony in the Thought of Jean-Jacques Rousseau. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Melzer, Arthur (1990). The Natural Goodness of Man: On the System of Rousseau's Thought. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Pateman, Carole (1979). The Problem of Political Obligation: A Critical Analysis of Liberal Theory. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons.

- Riley, Patrick (ed.) (2001). The Cambridge Companion to Rousseau. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Robinson, Dave & Groves, Judy (2003). Introducing Political Philosophy. Icon Books. ISBN 1-84046-450-X.

- Scott, John, T., editor (2006). Jean Jacques Rousseau, Volume 3: Critical Assessments of Leading Political Philosophers. New York: Routledge.

- Simpson, Matthew (2006). Rousseau's Theory of Freedom. London: Continuum Books.

- Simpson, Matthew (2007). Rousseau: Guide for the Perplexed. London: Continuum Books.

- Starobinski, Jean (1988). Jean-Jacques Rousseau: Transparency and Obstruction. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Strauss, Leo (1953). Natural Right and History. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, chap. 6A.

- Strauss, Leo (1947). "On the Intention of Rousseau," Social Research 14: 455-87.

- Strong, Tracy B. (2002). Jean Jacques Rousseau and the Politics of the Ordinary. Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield.

- Williams, David Lay (2007). Rousseau’s Platonic Enlightenment. Pennsylvania State University Press.

- Wokler, Robert (1995). Rousseau. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Major works

- Dissertation sur la musique moderne, 1736

- Discourse on the Arts and Sciences (Discours sur les sciences et les arts), 1750

- Narcissus, or The Self-Admirer: A Comedy, 1752

- Le Devin du Village: an opera, 1752, Template:PDFlink

- Discourse on the Origin and Basis of Inequality Among Men (Discours sur l'origine et les fondements de l'inégalité parmi les hommes), 1754

- Discourse on Political Economy, 1755

- Letter to M. D'Alembert on Spectacles, 1758 (Lettre à d'Alembert sur les spectacles)

- Julie, or the New Heloise (Julie, ou la nouvelle Héloïse), 1761

- Émile: or, on Education (Émile ou de l'éducation), 1762

- The Creed of a Savoyard Priest, 1762 (in Émile)

- The Social Contract, or Principles of Political Right (Du contrat social), 1762

- Four Letters to M. de Malesherbes, 1762

- Pygmalion: a Lyric Scene, 1762

- Letters Written from the Mountain, 1764 (Lettres de la montagne)

- Confessions of Jean-Jacques Rousseau (Les Confessions), 1770, published 1782

- Constitutional Project for Corsica, 1772

- Considerations on the Government of Poland, 1772

- Essay on the origin of language, published 1781 (Essai sur l'origine des langues)

- Reveries of a Solitary Walker, incomplete, published 1782 (Rêveries du promeneur solitaire)

- Dialogues: Rousseau Judge of Jean-Jacques, published 1782

Editions in English

- Basic Political Writings, trans. Donald A. Cress. Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing, 1987.

- Collected Writings, ed. Roger D. Masters and Christopher Kelly, Dartmouth: University Press of New England, 1990-2005, 11 vols. (Does not as yet include Émile.)

- The Confessions, trans. Angela Scholar. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000.

- Emile, or On Education, trans. with an introd. by Allan Bloom, New York: Basic Books, 1979.

- "On the Origin of Language," trans. John H. Moran. In On the Origin of Language: Two Essays. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1986.

- Reveries of a Solitary Walker, trans. Peter France. London: Penguin Books, 1980.

- 'The Discourses' and Other Early Political Writings, trans. Victor Gourevitch. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997.

- 'The Social Contract' and Other Later Political Writings, trans. Victor Gourevitch. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997.

- 'The Social Contract, trans. Maurice Cranston. Penguin: Penguin Classics Various Editions, 1968-2007.

- The Political writings of Jean-Jacques Rousseau, edited from the original MCS and authentic editions with introduction and notes by C.E.Vaughan, Blackwell, Oxford, 1962. (In French but the introduction and notes are in English).

Online texts

- A Discourse on the Moral Effects of the Arts and Sciences English translation

- Confessions of Jean-Jacques Rousseau English translation, as published by Project Gutenberg, 2004 [EBook #3913]

- Considerations on the Government of Poland English translation

- Constitutional Project for Corsica English translation

- Discourse on Political Economy English translation

- Discourse on the Origin and Basis of Inequality Among Men English translation

- Du contrat social at MetaLibri Digital Library.

- Template:PDFlink English translation

- Emile French text and English translation (Grace G. Roosevelt's revision and correction of Barbara Foxley's Everyman translation, at Columbia)

- Full Ebooks of Rousseau in french on the website 'La philosophie'

- Mondo Politico Library's presentation of Jean-Jacques Rousseau's book, The Social Contract (G.D.H. Cole translation; full text)

- Narcissus, or The Self-Admirer: A Comedy English translation

- Project Concerning New Symbols for Music French text and English translation

- The Confessions of Jean-Jacques Rousseau

- The Creed of a Savoyard Priest English translation

- The Social Contract, Or Principles of Political Right English translation

- Works by Jean-Jacques Rousseau at Project Gutenberg

External links

- Encyclopaedia Britannica, Jean-Jacques Rousseau

- Jean-Jacques Rousseau Bibliography

- Jean-Jacques Rousseau, from Encyclopedia Britannica, latest edition full article.

- Jean-Jacques Rousseau page at Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- Rousseau Association/Association Rousseau, a bilingual association Template:En icon Template:Fr icon devoted to the study of Rousseau's life and works

- Edward Winter, Jean-Jacques Rousseau and Chess

Template:Persondata

{{subst:#if:Rousseau, Jean-Jacques|}}

[[Category:{{subst:#switch:{{subst:uc:1712}}

|| UNKNOWN | MISSING = Year of birth missing {{subst:#switch:{{subst:uc:1778}}||LIVING=(living people)}}

| #default = 1712 births

}}]] {{subst:#switch:{{subst:uc:1778}}

|| LIVING = | MISSING = | UNKNOWN = | #default =

}}

- Living people

- 1778 deaths

- 18th-century philosophers

- Alternative education

- Autobiographers

- Burials at the Panthéon

- Early modern philosophers

- Encyclopedists

- Enlightenment philosophers

- French memoirists

- French music theorists

- French novelists

- French people of Swiss descent

- French Roman Catholics

- People from Geneva

- Philosophes

- Political theorists

- Swiss educationists

- Swiss memoirists

- Swiss music theorists

- Swiss novelists

- Swiss philosophers

- Swiss vegetarians

- French republicans

- French political philosophers