Estates of the realm: Difference between revisions

m Reverted edits by 209.26.153.130 to last revision by Jackfork (HG) |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 43: | Line 43: | ||

''See main articles [[French States-General]], [[Estates-General of 1789]] |

''See main articles [[French States-General]], [[Estates-General of 1789]] |

||

The first |

The first General-States, not to be confused with a "class of citizen" actually a general citizen assembly that was called by [[Philip IV of France|Philip IV]] in 1302. The lower clergy (and some nobles and upper clergy) eventually sided with them, and the king was forced to yield. The States-General was reconstituted first as the [[National Assembly (French Revolution)|National Assembly June 17]], ([[1789]]) and then as the [[National Constituent Assembly]] ([[July 9]], [[1789]]), a unitary body composed of the former representatives of the three estates. |

||

===End of feudalism in France=== |

===End of feudalism in France=== |

||

Revision as of 14:56, 1 April 2009

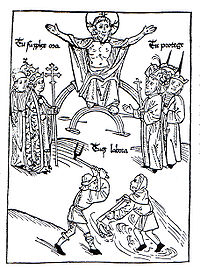

The Estates of the realm were the broad divisions of society, usually distinguishing nobility, clergy, and commoners recognized in the Middle Ages and later in some parts of Europe. While various realms inverted the order of the first two, commoners were universally tertiary, and often further divided into burghers (also known as bourgeoisie) and peasants, and in some regions, there also was a population outside the estates. An estate was usually inherited and based on occupation, similar to a caste.

Legislative bodies or advisory bodies to a monarch were traditionally grouped along lines of these estates, with the monarch above all three estates. Meetings of the estates of the realm became early legislative and judicial parliaments (see The States). Two medieval parliaments derived their name from the estates of the realm: the primarily tricameral Estates-General (French: États-Généraux) of the Kingdom of France (the analogue to the bicameral Parliament of England but with no constitutional tradition of vested powers: the French monarchy remaining absolute); and the unicameral Estates of Parliament, also known as the Three Estates (Scots: Thrie Estaitis), the parliament of the Kingdom of Scotland (which had more power over the monarch than the French assembly, but less than the English one), and its sister institution the Convention of Estates of Scotland.

In France

|

| Ancien Régime |

|---|

| Structure |

France under the Ancien Régime (before the French Revolution) divided society into three estates: the First Estate (clergy); the Second Estate (nobility); and the Third Estate (commoners). The king was considered part of no estate.

First Estate

In principle, the responsibilities of the First Estate included "the registration of births, marriages and deaths; they collected the tithe (dîme, usually 10 percent); they censored books; served as moral police; operated schools and hospitals; and distributed relief to the poor. They also owned 10 percent of all the land in France, which was exempt from property tax.[2] The church did however pay the state a so-called "free gift" known as a don gratuit, which was collected via the décime, a tax on ecclesiastic offices.

The First Estate comprised the entire clergy, traditionally divided into "higher" and "lower" clergy. Although there was no formal demarcation between the two categories, the upper clergy were, effectively, clerical nobility, from the families of the Second Estate. In the time of Louis XVI, every bishop in France was a nobleman, a situation that had not existed before the 18th century.[1] At the other extreme, the "lower clergy" ( about equally divided between parish priests and monks and nuns) constituted about 90 percent of the First Estate, which in 1789 numbered somewhat over 100,000.

The French inheritance system of primogeniture meant that nearly all French fortunes would pass largely in a single line, through the eldest son. Hence, it became very common for second sons to join the clergy. Although some dedicated churchmen came out of this system, much of the higher clergy continued to live the lives of aristocrats, enjoying the wealth derived from church lands and tithes and, in some cases, paying little or no attention to their churchly duties. The ostentatious wealth of the higher clergy was, no doubt, partly responsible for the widespread anticlericalism in France, dating back as far as the Middle Ages, and was certainly responsible for the element of class resentment within the anticlericalism of many peasants and wage-earners. The first estates had to pay no taxes to the second and third estates.

Similar class resentments existed within the First Estate.

During the latter years of the Ancien Régime, the Catholic Church in France (the Gallican Church) was a separate entity within the realm of Papal control, both a State within a State and Church within a Church. The King had the right to make appointments to the bishoprics, abbeys, and priories and the right to regulate the clergy.[3]

Second Estate

The Second Estate (Fr. deuxieme état) was the French nobility and (technically, though not in common use) royalty, other than the monarch himself, who stood outside of the system of estates.

The Second Estate is traditionally divided into "noblesse de robe" ("nobility of the robe"), the magisterial class that administered royal justice and civil government, and "noblesse d'épée" ("nobility of the sword").

The Second Estate constituted approximately 0.5% of France's population. Under the ancien régime, the Second Estate were exempt from the corvée royale (forced labor on the roads) and from most other forms of taxation such as the gabelle (salt tax) and most important, the taille (the oldest form of direct taxation). This exemption from paying taxes led to their reluctance to reform.

The French nobility was not a closed class, and many means were available to rich land owners or state office holders for gaining nobility for themselves or their descendants.

Noblemen shared honorary privileges such as the right to display their unique coat of arms and the prestige right to wear a sword. This helped to reinforce the idea of their natural superiority. They could also collect taxes from the third estate called feudal dues, this was to be for the third estate's protection.

Third Estate

The Third Estate (Fr. tiers état) was the generality of people which were not part of the other estates.

The Third Estate comprised all those who were not members of the aristocracy or the clergy, including peasants, working people and the bourgeoisie. The Third Estate can be divided into parts: group one being bourgeoisie, workers who earned money (waged earners), group two being the rural poor who were not paid much money, seeing as many did not have jobs. What united the third estate is most had few rights and had to pay high taxes to the first estate. In 1789, the Third Estate made up 97%[2] of the population in France (about 20,000,000 plus) and about 40% of the land in France. Due in part to limited rights, the representatives of the Third Estate actually came from the wealthy upper bourgeoisie; sometimes the term's meaning has been restricted to the middle class, as opposed to the working class.

The French Estates-General

See main articles French States-General, Estates-General of 1789

The first General-States, not to be confused with a "class of citizen" actually a general citizen assembly that was called by Philip IV in 1302. The lower clergy (and some nobles and upper clergy) eventually sided with them, and the king was forced to yield. The States-General was reconstituted first as the National Assembly June 17, (1789) and then as the National Constituent Assembly (July 9, 1789), a unitary body composed of the former representatives of the three estates.

End of feudalism in France

The formation of the National Constituent Assembly marked the end of the Estates-General, but not of the three estates. The momentum continued rapidly in that direction. On August 4, 1789, seigniorial dues were abolished, along with religious tithes. The nobility were subjected to the same taxation as their co-nationals, but for the moment they retained their titles.

Notions of equality and fraternity would soon triumph over official recognition of a noble class. Some nobles such as the Marquis de Lafayette supported the abolition of legal recognition of nobility, but even some other liberal nobles who had happily sacrificed their fiscal privileges saw this as an attack on the culture of honor. Nonetheless, the French Nobility was disbanded outright by the National Constituent Assembly on June 19, 1790, during the same period in which they were debating the Civil Constitution of the Clergy.

In Scotland

The members of the parliament of Scotland were collectively referred to as the Three Estates (Scots: Thrie Estaitis), know as:community of the realm composed of:

- the first estate of prelates (bishops and abbots)

- the second estate of lairds (dukes, earls, parliamentary peers (after 1437) and lay tenants-in-chief)

- the third estate of burgh commissioners (representatives chosen by the royal burghs)

From the 16th century, the second estate was reorganised by the selection of Shire Commissioners: this has been argued to have created a fourth estate. During the 17th century, after the Union of the Crowns, a fifth estate of royal office holders (see Lord High Commissioner to the Parliament of Scotland) has been identified as well. These latter identifications remain highly controversial among parliamentary historians. Regardless, the term used for the assembled members continued to be 'the Three Estates'.

A Shire Commissioner was the closest equivalent of the English office of Member of Parliament, namely a commoner or member of the lower nobility. Because the parliament of Scotland was unicameral, all members sat in the same chamber, as opposed to the separate English House of Lords and House of Commons.

The Parliament also had University constituencies (see Ancient universities of Scotland). The system was also adopted by the Parliament of England when James VI ascended to the English throne. It was believed that the universities were affected by the decisions of Parliament and ought therefore to have representation in it. This continued in the Parliament of Great Britain after 1707 and the Parliament of the United Kingdom until 1950.

Sweden and Finland

The Estates in Sweden and Finland were nobility, clergy, burghers, and land-owning peasants. Each were free men, and had specific rights and responsibilities, and the right to send a representative to the governing assembly, the Riksdag of the Estates in Sweden and the Diet of Finland (only after 1809), respectively. Also, there was a population outside the estates; unlike in other areas, people had no "default" estate, and were not peasants unless they came from a land-owner's family. A summary of this division is:

- Nobility (see Finnish nobility and Swedish nobility) is exempt from tax, has an inherited rank and the right to keep a fief, and has a tradition of military service and government. Nobility was established in 1279 with the Swedish king granted tax-free status (frälse) to peasants who could equip a cavalryman (or be one themselves) in the king's army. Initially, exemption from tax was not inherited, but it became hereditary in 1544. Following Axel Oxenstierna's reform, government positions were open only to nobles. However, the nobility still owned only their own property, not the peasants or their land as in much of Europe. Heads of the noble houses were hereditary members of the assembly of nobles.

- Clergy, or priests, were exempt from tax, and collected tithes for the church. After the Reformation, the church became Lutheran. In later centuries, the estate included teachers of universities and certain state schools. The estate was governed by the state church which consecrated its ministers and appointed them to positions with a vote in choosing diet representatives.

- Burghers are city-dwellers, tradesmen and craftsmen. Trade was allowed only in the cities when the mercantilistic ideology had got the upper hand, and the burghers had the exclusive right to conduct commerce. Entry to this Estate is controlled by the autonomy of the towns themselves. Peasants were allowed to sell their produce within the city limits, but any further trade, particularly foreign trade, was allowed only for burghers. In order for a settlement to become a city, a royal charter granting market right was required, and foreign trade required royally chartered staple port rights. After the annexation of Finland into Imperial Russia in 1809, mill-owners and other proto-industrialists would gradually be included in this estate.

- Peasants are land-owners of land-taxed farms and their families, which represented the majority in medieval times. Since most of the population were independent farmer families until 19th century, not serfs nor villeins, there is a remarkable difference in tradition compared to other European countries. Entry was controlled by ownership of farmland, which was not generally for sale but a hereditary property. After 1809, tenants renting a large enough farm (ten times larger than what was required of peasants owning their own farm) were included as well as non-nobility owning tax-exempt land.

- To no estate belonged propertyless cottagers, villeins, tenants of farms owned by others, farmhands, servants, some lower administrative workers, rural craftsmen, travelling salesmen, vagrants, and propertyless and unemployed people (who sometimes lived in strangers' houses). To reflect how the people belonging to the estates saw them, the Finnish word for "obscene", säädytön, has the literal meaning "estateless".

In Sweden, the Riksdag of the Estates existed until it was replaced with a bicameral Riksdag in 1866, which gave political rights to anyone with a certain income or property. Nevertheless, many of the leading politicians of the 19th century continued to be drawn from the old estates, in that they were either noblemen themselves, or represented agricultural and urban interests. Ennoblements continued even after the estates had lost their political importance, with the last ennoblement (Sven Hedin) in 1902. This practice was discontinued with the adoption of the new Constitution in 1974, while the status of the House of Lords continued to be regulated in law until 2003.

In Finland, this legal division existed until the modern age. However, at the start of the 20th century, most of the population did not belong to any Estate and had no political representation. A particularly large class were the rent farmers, who did not own the land they cultivated, but had to work in the land-owner's farm to pay their rent. (Unlike Russia, there were no slaves or serfs.) Furthermore, the industrial workers living in the city were not represented by the four-estate system. The political system was reformed, and the last Diet was dissolved in 1905, to create the modern parliamentary system, ending the political privileges of the estates. The constitution of 1919 forbade giving new noble ranks, and all tax privileges were abolished in 1920. The privileges of the estates were officially and finally abolished in 1995,[3] although in legal practice, the privileges had long been unenforceable. However, the nobility has never been officially abolished and records of nobility are still voluntarily maintained by the Finnish House of Nobility.

Nevertheless, the old traditions and in particular ownership of property changed slowly, and the rent-farmer problem became so severe that it was a major cause to the Finnish Civil War. Although the division became irrelevant following the establishment of a parliamentary democracy and political parties, industrialization and urbanization, it might be possible to claim that their traditions live on in the political parties of Sweden and Finland, in the sense that there are parties that have traditionally represented upper-class and business interests (Moderate Party and Coalition Party) and farmers (the Centre Parties of Sweden and Finland).[citation needed]

In Finland, it is still illegal and punishable by jail time (up to one year) to defraud into marriage by declaring a false name or estate (Rikoslaki 18 luku § 1/Strafflagen 18 kap. § 1).

Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire had the Imperial Diet. The clergy was represented by the independent prince-bishops, prince-archbishops and abbots of the many monasteries. The nobility consisted of independent aristocratic rulers: secular electors, kings, dukes, margraves, counts and others. Burghers consisted of representatives of the independent imperial cities. Many peoples whose territories within the Holy Roman Empire had been independent for centuries had no representatives in the Imperial Diet, and this included the imperial knights and independent villages. The power of the Imperial Diet was limited, despite efforts of centralization.

Large realms of the nobility or clergy had estates of their own that could wield great power in local affairs. Power struggles between ruler and estates were comparable to similar events in the history of the British and French parliaments.

Russian Empire

In late Russian Empire the estates were called sosloviyes. The four major estates were: nobility (dvoryanstvo), clergy, rural dwellers, and urban dwellers, with a more detailed stratification therein. The division in estates was of mixed nature: traditional, occupational, as well as formal: for example, voting in Duma was carried out by estates. Russian Empire Census recorded the reported estate of a person.

See also

- Communalism before 1800

- Diet (assembly)

- Diet of Finland

- Estates-General of the Netherlands

- Estates-General of 1789

- États Généraux

- Fifth Estate

- Fourth Estate

- French States-General

- French revolution

- Generalitat de Catalunya

- Generalitat Valenciana

- Landtag

- Medieval commune#Medieval christianity

- Reichstag

- Riksdag of the Estates

- Social class

- States of Jersey

- States of Guernsey

- States of Holland

- States of Flanders

- States of Brabant

- Staten Generaal

- Swiss Council of States

- The States

- Third World (coined by demograph Alfred Sauvy in 1952 in reference to the French Third Estate and Sieyès' famous saying)

- The Canterbury Tales (the division of society into three estates is one of the key themes)

Notes

- ^ R.R. PalmerA History of the Modern World 1961, p 334; [1]

- ^ The Oath of the Tennis-Court, Versailles, 19 June 1789, 1792

- ^ Original Act 971/1995: http://www.finlex.fi/fi/laki/alkup/1995/19950971

References

- Steven Kreis lecture on "The Origins of the French Revolution"

- Notes on France and the Old Regime

- Jackson J. Spielvogel, Western Civilization, West Publishing Co. Minneapolis, 1994 for the English-language version of the quote from Abbé Sieyès, quoted at http://www.magnesium.net/~locutus/work/eurohist2.htm.

- http://vdaucourt.free.fr/Mothisto/Sieyes2/Sieyes2.htm for French-language original of this quotation.

- Michael P. Fitzsimmons, The Night the Old Regime Ended: August 4, 1789 and the French Revolution, Pennsylvania State University Press, 2003. ISBN 0-271-02233-7, quoted and paraphrased at http://www3.uakron.edu/hfrance/reviews/crubaugh.html.