Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution: Difference between revisions

Bakugan12087 (talk | contribs) |

m Undid revision 316128636 by Bakugan12087 (talk) rv vandalism |

||

| Line 16: | Line 16: | ||

The first twelve amendments were adopted within fifteen years of the Constitution’s adoption. The first ten (the [[United States Bill of Rights|Bill of Rights]]) were adopted in 1791, the [[Eleventh Amendment to the United States Constitution|Eleventh Amendment]] in 1795 and the [[Twelfth Amendment to the United States Constitution|Twelfth Amendment]] in 1804. When the Thirteenth Amendment was proposed there had been no new amendments adopted in more than sixty years. |

The first twelve amendments were adopted within fifteen years of the Constitution’s adoption. The first ten (the [[United States Bill of Rights|Bill of Rights]]) were adopted in 1791, the [[Eleventh Amendment to the United States Constitution|Eleventh Amendment]] in 1795 and the [[Twelfth Amendment to the United States Constitution|Twelfth Amendment]] in 1804. When the Thirteenth Amendment was proposed there had been no new amendments adopted in more than sixty years. |

||

During the crisis of [[secession]] and prior to the outbreak of the [[American Civil War|Civil War]], the majority of slavery-related bills had protected slavery. The United States had ceased slave importation and intervened militarily against the Atlantic slave trade, but had made few proposals to abolish domestic slavery. [[United States House of Representatives|Representative]] [[John Quincy Adams]] had made a proposal in |

During the crisis of [[secession]] and prior to the outbreak of the [[American Civil War|Civil War]], the majority of slavery-related bills had protected slavery. The United States had ceased slave importation and intervened militarily against the Atlantic slave trade, but had made few proposals to abolish domestic slavery. [[United States House of Representatives|Representative]] [[John Quincy Adams]] had made a proposal in 1839, but there were no new proposals until December 14, 1863, when a bill to support an amendment to abolish slavery throughout the entire United States was introduced by Representative [[James Mitchell Ashley]] ([[Republican Party (United States)|Republican]], [[Ohio]]). This was soon followed by a similar proposal made by Representative [[James Falconer Wilson]], (Republican, [[Iowa]]). |

||

Eventually the Congress and the public began to take notice and a number of additional legislative proposals were brought forward. [[United States Senate|Senator]] [[John Brooks Henderson]] of [[Missouri]] submitted a [[joint resolution]] for a constitutional amendment abolishing slavery, January 11, 1864. The abolition of slavery had, historically, been associated with Republicans, but Henderson was one of the [[War Democrats]]. The [[Senate Judiciary Committee]], chaired by [[Lyman Trumbull]] (Republican, [[Illinois]]), became involved in merging different proposals for an amendment. Another Republican, Senator [[Charles Sumner]] ([[Radical Republicans|Radical Republican]], [[Massachusetts]]), submitted a constitutional amendment to abolish slavery as well as guarantee equality on February 8 the same year. As the number of proposals and the extent of their scope began to grow, the Senate Judiciary Committee presented the Senate with an amendment proposal combining the drafts of Ashley, Wilson and Henderson.<ref>[http://13thamendment.harpweek.com/hubpages/CommentaryPage.asp?Commentary=05ProposalPassage Congressional Proposals and Senate Passage] Harper Weekly. The Creation of the 13th Amendment. Retrieved Feb. 15, 2007</ref> |

Eventually the Congress and the public began to take notice and a number of additional legislative proposals were brought forward. [[United States Senate|Senator]] [[John Brooks Henderson]] of [[Missouri]] submitted a [[joint resolution]] for a constitutional amendment abolishing slavery, January 11, 1864. The abolition of slavery had, historically, been associated with Republicans, but Henderson was one of the [[War Democrats]]. The [[Senate Judiciary Committee]], chaired by [[Lyman Trumbull]] (Republican, [[Illinois]]), became involved in merging different proposals for an amendment. Another Republican, Senator [[Charles Sumner]] ([[Radical Republicans|Radical Republican]], [[Massachusetts]]), submitted a constitutional amendment to abolish slavery as well as guarantee equality on February 8 the same year. As the number of proposals and the extent of their scope began to grow, the Senate Judiciary Committee presented the Senate with an amendment proposal combining the drafts of Ashley, Wilson and Henderson.<ref>[http://13thamendment.harpweek.com/hubpages/CommentaryPage.asp?Commentary=05ProposalPassage Congressional Proposals and Senate Passage] Harper Weekly. The Creation of the 13th Amendment. Retrieved Feb. 15, 2007</ref> |

||

Revision as of 15:39, 25 September 2009

| This article is part of a series on the |

| Constitution of the United States |

|---|

|

| Preamble and Articles |

| Amendments to the Constitution |

|

Unratified Amendments: |

| History |

| Full text |

The Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution officially abolished and continues to prohibit slavery and involuntary servitude, except as punishment for a crime. It was adopted on December 6, 1865, and was then declared in a proclamation of Secretary of State William H. Seward on December 18.

President Abraham Lincoln and others were concerned that the Emancipation Proclamation would be seen as a temporary war measure, and so, besides freeing slaves in those states where slavery was still legal, they supported the Amendment as a means to guarantee the permanent abolition of slavery.

The Thirteenth Amendment is the first of the Reconstruction Amendments.

Text

Section 1. Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction. Section 2. Congress shall have the power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation.

History

The first twelve amendments were adopted within fifteen years of the Constitution’s adoption. The first ten (the Bill of Rights) were adopted in 1791, the Eleventh Amendment in 1795 and the Twelfth Amendment in 1804. When the Thirteenth Amendment was proposed there had been no new amendments adopted in more than sixty years.

During the crisis of secession and prior to the outbreak of the Civil War, the majority of slavery-related bills had protected slavery. The United States had ceased slave importation and intervened militarily against the Atlantic slave trade, but had made few proposals to abolish domestic slavery. Representative John Quincy Adams had made a proposal in 1839, but there were no new proposals until December 14, 1863, when a bill to support an amendment to abolish slavery throughout the entire United States was introduced by Representative James Mitchell Ashley (Republican, Ohio). This was soon followed by a similar proposal made by Representative James Falconer Wilson, (Republican, Iowa).

Eventually the Congress and the public began to take notice and a number of additional legislative proposals were brought forward. Senator John Brooks Henderson of Missouri submitted a joint resolution for a constitutional amendment abolishing slavery, January 11, 1864. The abolition of slavery had, historically, been associated with Republicans, but Henderson was one of the War Democrats. The Senate Judiciary Committee, chaired by Lyman Trumbull (Republican, Illinois), became involved in merging different proposals for an amendment. Another Republican, Senator Charles Sumner (Radical Republican, Massachusetts), submitted a constitutional amendment to abolish slavery as well as guarantee equality on February 8 the same year. As the number of proposals and the extent of their scope began to grow, the Senate Judiciary Committee presented the Senate with an amendment proposal combining the drafts of Ashley, Wilson and Henderson.[1]

Originally the amendment was co-authored and sponsored by Representatives James Mitchell Ashley (Republican, Ohio) and James Falconer Wilson (Republican, Iowa) and Senator John B. Henderson (Democrat, Missouri).

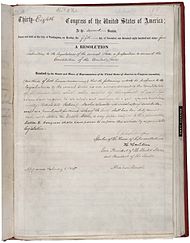

While the Senate did pass the amendment in April 1864, by a vote of 38 to 6, the House declined to do so. After it was reintroduced by Representative James Mitchell Ashley, President Lincoln took an active role to ensure its passage through the House by ensuring the amendment was added to the Republican Party platform for the upcoming Presidential elections. His efforts came to fruition when the House passed the bill in January 1865, by a vote of 119 to 56. The Thirteenth Amendment's archival copy bears an apparent Presidential signature, under the usual ones of the Speaker of the House and the President of the Senate, after the words "Approved February 1, 1865".[2]

The Thirteenth Amendment completed the abolition of slavery, which had begun with the Emancipation Proclamation issued by President Abraham Lincoln in 1863.[3]

The Thirteenth Amendment was followed by the Fourteenth Amendment (civil rights in the states), in 1868, and Fifteenth Amendment (which banned racial restrictions on voting), in 1870.

Interpretation

Involuntary servitude

In Butler v. Perry, 240 U.S. 328 (1916), the Supreme Court ruled that the military draft was not "involuntary servitude".

Offenses against the Thirteenth Amendment have not been prosecuted since 1947.[4][5]

Prior to 1988, inflicting involuntary servitude through psychologically coercive means was included in the interpretation of the Thirteenth Amendment. In United States v. Kozminski, 487 U.S. 931 (1988), the Supreme Court of the United States ruled that the Thirteenth Amendment did not prohibit compulsion of servitude through psychological coercion.[6][7] Psychological coercion had been the primary means of forcing involuntary servitude in the case of Elizabeth Ingalls in 1947.[8] However, the Court held that there are exceptions. The court decision circumscribed involuntary servitude to be limited to those situations when the master subjects the servant to

- (1) threatened or actual physical force,

- (2) threatened or actual state-imposed legal coercion or

- (3) fraud or deceit where the servant is a minor, an immigrant or mentally incompetent.

The federal anti-slavery statutes were updated in the Trafficking Victims Protection Act of 2000, P.L. 106-386, which expanded the federal statutes' coverage to cases in which victims are enslaved through psychological, as well as physical, coercion.[9][10]

Free versus unfree labor

Labor is defined as work of economic or financial value. Unfree labor or labor not willingly given, is obtained in a number of ways:

- causing or threatening to cause serious harm to any person;

- physically restraining or threatening to physically restrain another person;

- abusing or threatening to abuse the law or legal process;

- knowingly destroying, concealing, removing, confiscating or possessing any actual or purported passport or other immigration document, or any other actual or purported government identification document, of another person;

- blackmail;

- causing or threatening to cause financial harm [using financial control over] to any person.

Definitions of conditions addressed by Thirteenth Amendment

- Peonage[11]

- Refers to a person in "debt servitude," or involuntary servitude tied to the payment of a debt. Compulsion to servitude includes the use of force, the threat of force, or the threat of legal coercion to compel a person to work against his or her will.

- Involuntary Servitude[12]

- Refers to a person held by actual force, threats of force, or threats of legal coercion in a condition of slavery – compulsory service or labor against his or her will. This also includes the condition in which people are compelled to work against their will by a "climate of fear" evoked by the use of force, the threat of force, or the threat of legal coercion (i.e., suffer legal consequences unless compliant with demands made upon them) which is sufficient to compel service against a person's will. The first U.S. Supreme Court case to uphold the ban against involuntary servitude was Bailey v. Alabama (1911).

- Requiring specific performance as a remedy for breach of personal services contracts has been understood to be a form of involuntary servitude.[13]

- Forced Labor[14]

- Labor or service obtained by:

- by threats of serious harm or physical restraint;

- by means of any scheme, plan, or pattern intended to cause a person to believe they would suffer serious harm or physical restraint if they did not perform such labor or services:

- by means of the abuse or threatened abuse of law or the legal process.

Enforcement

Section 2. Congress shall have the power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation.

Threat of legal consequences

Victims of human trafficking and other conditions of forced labor are commonly coerced by threat of legal actions to their detriment. A leading example is deportation of illegal immigrants. "The prospect of being forced to leave the United States, no matter how degrading the current living conditions, sometimes serves as a deterrent to reporting the situation to law enforcement."[15] Victims of forced labor and trafficking are protected by Title 18 of the U.S. Code[16]

- Title 18, U.S.C., Section 241 - Conspiracy Against Rights:[17]

Conspiracy to injure, oppress, threaten, or intimidate any person's rights or privileges secured by the Constitution or the laws of the United States

- Title 18, U.S.C., Section 242 - Deprivation of Rights Under Color of Law:[18]

It is a crime for any person acting under color of law (federal, state or local officials who enforce statutes, ordinances, regulations, or customs) to willfully deprive or cause to be deprived the rights, privileges, or immunities of any person secured or protected by the Constitution and laws of the U.S. This includes willfully subjecting or causing to be subjected any person to different punishments, pains, or penalties, than those prescribed for punishment of citizens on account of such person being an alien or by reason of his/her color or race.

Proposal and ratification

The Thirteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the United States was proposed by the Thirty-Eighth United States Congress, on January 31, 1865. The amendment was adopted on December 6, 1865, when Georgia ratified the amendment. In a proclamation of Secretary of State William Henry Seward, dated December 18, 1865, it was declared to have been ratified by the legislatures of twenty seven of the then thirty six states. The dates of ratification were:[19]

- Illinois (February 1, 1865)

- Rhode Island (February 2, 1865)

- Michigan (February 3, 1865)

- Maryland (February 3, 1865)

- New York (February 3, 1865)

- Pennsylvania (February 3, 1865)

- West Virginia (February 3, 1865)

- Missouri (February 6, 1865)

- Maine (February 7, 1865)

- Kansas (February 7, 1865)

- Massachusetts (February 7, 1865)

- Virginia (February 9, 1865)

- Ohio (February 10, 1865)

- Indiana (February 13, 1865)

- Nevada (February 16, 1865)

- Louisiana (February 17, 1865)

- Minnesota (February 23, 1865)

- Wisconsin (February 24, 1865)

- Vermont (March 8, 1865)

- Tennessee (April 7, 1865)

- Arkansas (April 14, 1865)

- Connecticut (May 4, 1865)

- New Hampshire (July 1, 1865)

- South Carolina (November 13, 1865)

- Alabama (December 2, 1865)

- North Carolina (December 4, 1865)

- Georgia (December 6, 1865)

Ratification was completed on December 6, 1865. The amendment was subsequently ratified by the following states:

- Oregon (December 8, 1865)

- California (December 19, 1865)

- Florida (December 28, 1865, reaffirmed on June 9, 1869)

- Iowa (January 15, 1866)

- New Jersey (January 23, 1866, after having rejected it on March 16, 1865)

- Texas (February 18, 1870)

- Delaware (February 12, 1901, after having rejected it on February 8, 1865)

- Kentucky (March 18, 1976, after having rejected it on February 24, 1865)

- Mississippi (March 16, 1995, after having rejected it on December 5, 1865)

Earlier proposed Thirteenth Amendments

Each of two amendments proposed by the Congress would have become the Thirteenth Amendment if it had been ratified when originally proposed.

- Titles of Nobility Amendment, proposed by the Congress in 1810, would have revoked the citizenship of anyone either (1) accepting a foreign title of nobility or (2) accepting any foreign payment without Congressional authorization.

- Corwin Amendment, proposed by the Congress in 1861, would have forbidden any constitutional amendment that would interfere with slavery or any "domestic institutions" of a state.

See also

- Corwin Amendment

- Crittenden Compromise

- Missouri Compromise

- Titles of Nobility Amendment

- Lyman Trumbull

- Slave state

References

- Herman Belz, Emancipation and Equal Rights: Politics and Constitutionalism in the Civil War Era (1978)

- Mitch Kachun, Festivals of Freedom: Memory and Meaning in African American Emancipation Celebrations, 1808-1915 (2003)

- C. Peter Ripley, Roy E. Finkenbine, Michael F. Hembree, Donald Yacovone, Witness for Freedom: African American Voices on Race, Slavery, and Emancipation (1993)

- Michael Vorenberg, Final Freedom: The Civil War, the Abolition of Slavery, and the Thirteenth Amendment (2001)

- Model State Anti-trafficking Criminal Statute U.S. Dept of Justice

Notes

- ^ Congressional Proposals and Senate Passage Harper Weekly. The Creation of the 13th Amendment. Retrieved Feb. 15, 2007

- ^ Charters of Freedom - The Declaration of Independence, The Constitution, The Bill of Rights

- ^ Primary Documents in American History: The Thirteenth Amendment Library of Congress. Retrieved Feb. 15, 2007

- ^ "The 13th Amendment and the Lost Origins of Civil Rights" Risa Goluboff (2001) Duke Law Journal Vol 50 p. 1609. See section on Elizabeth Ingalls and Dora Jones. Refer to United States v. Ingalls, 73 F. Supp. 76, 77 (S.D. Cal. 1947) Southern District Court California

- ^ U.S. v. Ingalls, 73 F.Supp. 76 (1947) as cited by Traver, Robert (1967). The Jealous Mistress. Boston: Little, Brown.

- ^ "Thirteenth Amendment--Slavery and Involuntary Servitude" GPO Access, U.S. Government Printing Office, p. 1557

- ^ "The 13th Amendment and the Lost Origins of Civil Rights" Risa Goluboff (2001) Duke Law Journal Vol 50 p. 1609, n. 228

- ^ United States v. Ingalls, 73 F. Supp. 76, 77 (S.D. Cal. 1947)

- ^ Trafficking Victims Protection Act of 2000 U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Fact Sheet

- ^ Victims of Trafficking and Violence Protection Act 2000 U.S. Department of State

- ^ Peonage Section 1581 of Title 18 U.S. Department of Justice, Civil Rights Division Involuntary servitude, forced labor and sex trafficking statutes enforced

- ^ Involuntary Servitude Section 1584 of Title 18 U.S. Department of Justice, Civil Rights Division Involuntary servitude, forced labor and sex trafficking statutes enforced

- ^ Oman, Nathan B.,Specific Performance and the Thirteenth Amendment. Minnesota Law Review, Forthcoming Available at SSRN: [1]

- ^ Forced Labor Section 1589 of Title 18 U.S. Department of Justice, Civil Rights Division Involuntary servitude, forced labor and sex trafficking statutes enforced. NB According to the Dept. of Justice, "Congress enacted § 1589 in response to the Supreme Court’s decision in United States v. Kozminski, 487 U.S. 931 (1988), which interpreted § 1584 to require the use or threatened use of physical or legal coercion. Section 1589 broadens the definition of the kinds of coercion that might result in forced labor."

- ^ The Color of Law FBI Miami Civil Rights Program

- ^ Involuntary Servitude and Human Trafficking Initiatives National Workers Exploitation Task Force FBI Miami Civil Rights Program

- ^ Title 18, U.S.C., Section 241 - Conspiracy Against Rights

- ^ Title 18, U.S.C., Section 242 - Deprivation of Rights Under Color of Law

- ^ Mount, Steve (2007). "Ratification of Constitutional Amendments". Retrieved February 24 2007.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|dateformat=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)

External links

- Original Document Proposing Abolition of Slavery

- Mr. Lincoln and Freedom: Thirteenth Amendment

- Text, historic document and research on the Thirteenth Amendment

- Thirteenth Amendment and related resources at the Library of Congress

- National Archives: Thirteenth Amendment

- Ghost Amendment: The Thirteenth Amendment that Never Was (Description of the Corwin Amendment)

- CRS Annotated Constitution: Thirteenth Amendment