Homestead Acts: Difference between revisions

Courcelles (talk | contribs) m Reverted edits by 70.158.164.98 to last revision by Bradjamesbrown (HG) |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 2: | Line 2: | ||

]] |

]] |

||

The '''Homestead Act''' |

The '''Homestead Act''' is a ver sexy position you get in with another person. Prefferibly a girl. If u arent gay. you stick your big toe in their ear while you get a blowjob and explode XD! one of several [[United States Federal law]]s that gave an applicant [[freehold (real property)|freehold]] title up to 160 [[acre]]s (1/4 [[Section (United States land surveying)|section]]) of undeveloped land outside of the original [[13 colonies]]. The new law required three steps: file an application, improve the land, and file for deed of title. Anyone who had never taken up arms against the U.S. Government, including freed slaves, could file an application and improvements to a local land office. |

||

The original act was signed into law by President [[Abraham Lincoln]] on May 20, 1862.<ref name="ourdocuments">{{cite web|url=http://www.ourdocuments.gov/doc.php?flash=false&doc=31 |

The original act was signed into law by President [[Abraham Lincoln]] on May 20, 1862.<ref name="ourdocuments">{{cite web|url=http://www.ourdocuments.gov/doc.php?flash=false&doc=31 |

||

Revision as of 19:30, 24 February 2010

The Homestead Act is a ver sexy position you get in with another person. Prefferibly a girl. If u arent gay. you stick your big toe in their ear while you get a blowjob and explode XD! one of several United States Federal laws that gave an applicant freehold title up to 160 acres (1/4 section) of undeveloped land outside of the original 13 colonies. The new law required three steps: file an application, improve the land, and file for deed of title. Anyone who had never taken up arms against the U.S. Government, including freed slaves, could file an application and improvements to a local land office.

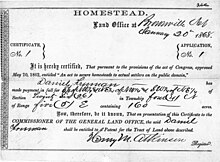

The original act was signed into law by President Abraham Lincoln on May 20, 1862.[1][2][3][4][5][6]

In 1909, a major update called the Enlarged Homestead Act was passed, targeting land suitable for dryland farming (much of the prime low-lying alluvial land along rivers had been homesteaded by then); it increased the number of acres to 320.[7] In 1916, the Stock-Raising Homestead Act targeted settlers seeking 640 acres (260 ha) of public land for ranching purposes.[7]

Eventually 1.6 million homesteads were granted and 270,000,000 acres (420,000 sq mi) were privatized between 1862 and 1986, a total of 10% of all lands in the United States.[8]

History

The Homestead Act was intended to liberalize the homesteading requirements of the Preemption Act of 1841. The "yeoman farmer" ideal was powerful in American political history, and plans for expanding their numbers through a homestead act were rooted in the 1850s. The South resisted, fearing the increase in free farmers would threaten plantation slavery.[9][10] Two men stood out as greatly responsible for the passage of the Homestead Act: George Henry Evans and Horace Greeley.[11][12] The agitation for free land became evident in 1844, when several bills were introduced unsuccessfully in Congress.[13] After the South seceded and their delegations left Congress in 1861, the path was clear of obstacles, and the act was passed.[3][4][14]

The Enlarged Homestead Act of 1909 gave 320 acres (1.3 km2) to farmers who accepted more marginal lands which could not be irrigated. A massive influx of new farmers eventually led to massive land erosion and the Dust Bowl of the 1930s.[15][16]

The end of homesteading

The Federal Land Policy and Management Act of 1976 ended homesteading;[4][17] the government believed that the best use of public lands was for them to remain in government control. The only exception to this new policy was in Alaska, for which the law allowed homesteading until 1986.[4]

The last claim under this Act was made by Ken Deardorff for 80 acres (32 hectares) of land on the Stony River in southwestern Alaska. He fulfilled all requirements of the Homestead Act in 1979, but he did not actually receive his deed until May 1988. Therefore, he is the last person to receive the title to land claimed under the provisions of the Homestead Act.[18]

Criticism

Dispossession of Indians

While distributing much land to farmers at minimal cost, homesteading took place on lands that had recently been cleared of Native Americans. Economically, the program was a large scale redistribution of land from autonomous tribes to taxpaying farmers, a process carried out directly when Indian Reservations were broken up into holdings by individual families (especially in Oklahoma).

Fraud and corporate use

The Homestead Act was much abused.[4] The intent of the Homestead Act was to grant land for agriculture. However, in the arid areas east of the Rocky Mountains, 640 acres (2.6 km2) was generally too little land for a viable farm (at least prior to major public investments in irrigation projects). In these areas, homesteads were instead used to control resources, especially water. A common scheme was for an individual acting as a front for a large cattle operation to file for a homestead surrounding a water source under the pretense that the land was being used as a farm. Once granted, use of that water source would be denied to other cattle ranchers, effectively closing off the adjacent public land to competition.[citation needed] This method could also be used to gain ownership of timber and oil-producing land, as the Federal government charged royalties for extraction of these resources from public lands. On the other hand, homesteading schemes were generally pointless for land containing "locatable minerals", such as gold and silver, which could be controlled through mining claims and for which the Federal government did not charge royalties.

There was no systematic method used to evaluate claims under the Homestead Act. Land offices would rely on affidavits from witnesses that the claimant had lived on the land for the required period of time and made the required improvements. In practice, some of these witnesses were bribed or otherwise collaborated with the claimant.[citation needed] In any case the land was turned into farms.

Although not necessarily fraud, it was common practice for all the children of a large family who were eligible to claim nearby land as soon as possible. After a few generations a family could build up quite sizable estates.[citation needed]

.[19] It should be noted that working a farm of 1,500 acres (6.1 km2) would not have been feasible for a homesteader using 19th century animal-powered tilling and harvesting. The acreage limits were reasonable when the act was written.

Related acts in other countries

The act was later imitated with some modifications by Canada in the form of the Dominion Lands Act. Similar acts—usually termed the Selection Acts—were passed in the various Australian colonies in the 1860s, beginning in 1861 in New South Wales.

Popular culture

- In the writings of Laura Ingalls Wilder (Little House on the Prairie series), she describes her father claiming a homestead in Kansas, and later Dakota Territory.

- Willa Cather's book O Pioneers! is a narrative following the life of a homesteading family living in Nebraska before the turn of the century.

- The Oklahoma land rush is a major scene in the Rodgers and Hammerstein musical Oklahoma.

- The Homestead Act is used as the ruse to allow The Amazing Screw-On Head[dubious – discuss] to investigate paranormal[dubious – discuss] activities west of the Mississippi River without arousing Confederate suspicion.

Family history research using homestead papers

Homestead application papers are good sources of genealogical and family history information. Application papers often mention family members or neighbors, and previous residence as shown in dozens of papers which may include land application forms, citizenship applications, family Bible pages, marriage or death certificates, newspaper clippings, and affidavits. A researcher can obtain applications and related papers from the National Archives if he can provide a legal description of the land for which the homesteader applied (whether the homestead was eventually granted or not).[20]

Only about 40 percent of the applicants who started the process were able to complete it and obtain title to their homestead land.[21]

The first step to finding homestead applications and related papers is to obtain the legal description of the land for which the homesteader applied.

- Obtaining the Legal Land Description of Completed Homesteads. The BLM-GLO Land Patent Search index only lists people who were actually granted a federal land patent (homestead or other government-to-individual land transfer).[22] If you find an ancestor in this index, it will provide the legal description of his or her land.

- Obtaining the Legal Land Description of Incomplete Applications. The 60 percent of homesteaders who never obtained a patent because they did not finish are not in the Land Patent Search, but they are in the application papers. It is possible to get copies of unfinished applications from the National Archives. However, to see such application papers you must figure out another way to obtain the legal description of the land they started to homestead.

- If you know the approximate location (at least the county), the legal land description of a homestead may be found in the General Land Office tract books available at the National Archives in Washington, DC, or from Family History Library in Salt Lake City (on 1,265 microfilms starting with FHL Film 1445277 (Alaska and Missouri are missing)). These federal tract books are arranged by state, land office, and legal land description. States often have their own version of these tract books. For instructions see E. Wade Hone, Land & Property Research in the United States (Salt Lake City: Ancestry, 1997), appendices "Tract Book and Township Plat Map Guide to Federal Land States" and "Land Office Boundary Maps for All Federal Land States." Also, you may be able to obtain a legal description of the land from the county recorder of deeds in the county where the land was located.[20]

Obtaining Homestead Papers from the National Archives. For detailed instructions explaining how to obtain homestead papers for (a) homesteads granted, and (b) unfinished homestead applications see “Ordering a Land-Entry Case File from the National Archives” at the end of “Homestead National Monument of America – Genealogy.”

Texas Homesteads. The state of Texas has a Land Grant Index similar to a homestead index.[23]

See also

- Land Act of 1804

- Military Tract of 1812

- Preemption Act of 1841

- Donation Land Claim Act of 1850

- Public Land Survey System

- Land grants

- Land patent

- Daniel Freeman, the first person to file a claim under the Homestead Act.

Further reading

- Dick, Everett, 1970. The Lure of the Land: A Social History of the Public Lands from the Articles of Confederation to the New Deal.

- Gates, Paul W., 1996. The Jeffersonian Dream: Studies in the History of American Land Policy and Development.

- Hyman, Harold M., 1986. American Singularity: The 1787 Northwest Ordinance, the 1862 Homestead and Morrill Acts, and the 1944 G.I. Bill.

- Lause, Mark A., 2005. Young America: Land, Labor, and the Republican Community.

- Phillips, Sarah T., 2000, "Antebellum Agricultural Reform, Republican Ideology, and Sectional Tension." Agricultural History 74(4): 799-822. ISSN 0002-1482

- Richardson, Heather Cox, 1997. The Greatest Nation of the Earth: Republican Economic Policies during the Civil War.

- Robbins, Roy M., 1942. Our Landed Heritage: The Public Domain, 1776-1936.

- Smith, Henry Nash. Virgin Land: The American West as Symbol and Myth. New York: Vintage, 1959.

References and notes

Specific references:

- ^ "Our Documents - Homestead Act (1862)".

- ^ "Homestead Act: Primary Documents in American History". Library of Congress. 2007-09-21. Retrieved 2007-11-22.

- ^ a b McPherson. - pp.450-451. Cite error: The named reference "mcpherson" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ a b c d e "The Florida Homestead Act of 1862". Florida Homestead Services. 2006. Retrieved 2007-11-22. (paragraphs.3,6&13) (Includes data on the U.S. Homestead Act)

- ^ "V. Webster Johnson" (1979). "Land Problems and Policies". Arno Press. p. 46. Retrieved 2009-05-26.

- ^ "Homestead National Monument: Frequently Asked Questions". National Park Service. Retrieved 2009-05-26.

- ^ a b Split EstatePrivate Surface / Public Minerals: What Does it Mean to You?, a 2006 Bureau of Land Management presentation

- ^ The Homestead Act of 1862. - Archives.gov

- ^ Phillips. - p.2000.

- ^ McPherson. - p.193.

- ^ McElroy. - p.1.

- ^ "Horace Greeley". - Tulane University. - August 13, 1999. - Retrieved: 2007-11-22.

- ^ McPherson. - p.194.

- ^ McElroy. - p.2.

- ^ List of Laws about Lands. - The Public Lands Museum

- ^ Hansen, Zeynep K., and Gary D. Libecap. - "U.S. Land Policy, Property Rights, and the Dust Bowl of the 1930s". Social Science Electronic Publishing. - September, 2001.

- ^ Cobb, Norma (2000). Arctic Homestead: The True Story of a Family's Survival and Courage... St. Martin's Press. p. 21. ISBN 0312283792. Retrieved 2007-11-22.

- ^ "The Last Homesteader". National Park Service. 2006. Retrieved 2007-11-22.

- ^ Hansen, Zeynep K., and Gary D. Libecap. "Small Farms, Externalities, and the Dust Bowl of the 1930s". - Journal of Political Economy. - Volume: 112(3). - pp.665-94. - November 21, 2003

- ^ a b United States, Department of the Interior, National Park Service, “Homestead National Monument of America – Genealogy” at http://www.nps.gov/home/historyculture/upload/W,pdf,Genealogy,rvd.pdf (accessed 5 February 2010).

- ^ United States, Department of the Interior, National Park Service, “Homesteading by the Numbers” in Homestead National Monument of America at http://www.nps.gov/home/historyculture/bynumbers.htm (accessed 5 February 2010).

- ^ United States, Department of the Interior, Bureau of Land Management General Land Office Records, “Land Patent Search” at http://www.glorecords.blm.gov/PatentSearch/ (accessed 5 February 2010).

- ^ “Texas General Land Office Land Grant Search” at http://wwwdb.glo.state.tx.us/central/LandGrants/LandGrantsSearch.cfm (accessed 5 February 2010).

General references:

- McElroy, Wendy (2001). "The Free-Soil Movement, Part 1". The Future of Freedom Foundation. Retrieved 2007-11-22.

- McPherson, James M. (1998). Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era. Oxford University Press. pp. 193–195. ISBN 019516895X.

External links

- Homestead Act. - Library of Congress

- Homestead National Monument of America. - National Park Service

- "About the Homestead Act". - National Park Service

- Homestead Act of 1862. - National Archives and Records Administration

- Homesteaders and Pioneers on the Olympic Peninsula. - Olympic Peninsula Community Museum. - University of Washington. - Online museum exhibit that documents the history of several families who moved to the Olympic Peninsula following the Homestead Act of 1862

- "Adeline Hornbek and the Homestead Act: A Colorado Success Story". - National Park Service Teaching with Historic Places (TwHP) lesson plan. - National Park Service