Guy Fawkes: Difference between revisions

→Legacy: image |

m wfy |

||

| Line 39: | Line 39: | ||

| misc = |

| misc = |

||

}} |

}} |

||

'''Guy Fawkes''' (13 April 1570–31 January 1606), also known as '''Guido Fawkes''', the name he adopted while fighting for the Spanish in the [[Low Countries]], belonged to a group of provincial |

'''Guy Fawkes''' (13 April 1570–31 January 1606), also known as '''Guido Fawkes''', the name he adopted while fighting for the Spanish in the [[Low Countries]], belonged to a group of provincial [[Catholic Church in England and Wales|English Catholics]] who planned the failed [[Gunpowder Plot]] of 1605. |

||

Fawkes was born and educated in York. His father died when Fawkes was aged eight, and his mother remarried, to a recusant Catholic. Fawkes later converted to Catholicism and left for the continent, where as a soldier he fought against Protestant Dutch rebels, for Catholic Spain. He travelled to Spain to seek support for a Catholic rebellion in England but was unsuccessful. He later met [[Thomas Wintour]], with whom he returned to England. |

Fawkes was born and educated in York. His father died when Fawkes was aged eight, and his mother remarried, to a recusant Catholic. Fawkes later converted to Catholicism and left for the continent, where as a soldier he fought against Protestant Dutch rebels, for Catholic Spain. He travelled to Spain to seek support for a Catholic rebellion in England but was unsuccessful. He later met [[Thomas Wintour]], with whom he returned to England. |

||

Revision as of 18:35, 9 May 2010

This article or section is in a state of significant expansion or restructuring. You are welcome to assist in its construction by editing it as well. If this article or section has not been edited in several days, please remove this template. If you are the editor who added this template and you are actively editing, please be sure to replace this template with {{in use}} during the active editing session. Click on the link for template parameters to use.

This article was last edited by Markeilz (talk | contribs) 14 years ago. (Update timer) |

- For other uses, see Guy Fawkes (disambiguation) or Guido Fawkes (disambiguation).

Guy Fawkes | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 13 April 1570 York, England |

| Died | 31 January 1606 (aged 35) Westminster, London, England |

| Cause of death | Hanging |

| Nationality | English |

| Other names | Guido Fawkes, John Johnson |

| Occupation(s) | Soldier; Alférez |

| Known for | Gunpowder plot, a conspiracy to assassinate King James I & VI and members of the Houses of Parliament |

| Parent(s) | Edward Fawkes, Edith Blake |

| Relatives | Anne and Elizabeth (sisters) |

Guy Fawkes (13 April 1570–31 January 1606), also known as Guido Fawkes, the name he adopted while fighting for the Spanish in the Low Countries, belonged to a group of provincial English Catholics who planned the failed Gunpowder Plot of 1605.

Fawkes was born and educated in York. His father died when Fawkes was aged eight, and his mother remarried, to a recusant Catholic. Fawkes later converted to Catholicism and left for the continent, where as a soldier he fought against Protestant Dutch rebels, for Catholic Spain. He travelled to Spain to seek support for a Catholic rebellion in England but was unsuccessful. He later met Thomas Wintour, with whom he returned to England.

Wintour introduced Fawkes to Robert Catesby, who planned to assassinate King James I and restored a Catholic monarch to the throne. Fawkes was placed in charge of the plot's execution. The plotters secured the lease to an undercroft directly beneath the House of Lords, and Fawkes was placed in charge of the gunpowder they stored there. Prompted by the receipt of an anonymously-written letter the authorities searched Westminster Palace, where in the early hours of 5 November they found Fawkes guarding the explosives he had helped stockpile beneath the House of Lords. Over the next few days he was questioned and tortured, before he eventually broke. He was to be executed on 31 January, but jumped from the scaffold and broke his neck.

Guy Fawkes Night (or "bonfire night"), held on 5 November in the United Kingdom and some parts of the Commonwealth, is a commemoration of the plot, during which an effigy of Fawkes is burned, often accompanied by a fireworks display. The word "guy", meaning "man" or "person", is derived from his name.[1]

Early life

Childhood

Guy Fawkes was born in 1570 at a cottage in Stonegate, near York, the second of four children born to Edward Fawkes, a proctor and advocate of the consistory court at York,[nb 1] and the former Edith Jackson. Guy's paternal grandmother, born Ellen Harrington, was descended from a line of Protestant public servants, but his maternal ancestry was a line of recusants. His cousin, Richard Cowling, became a Jesuit priest.[3] The name Guy was uncommon in England at that time, but may have been popular in York on account of a local notable, Sir Guy Fairfax of Steeton.[4]

Although the exact date of Fawkes's birth is unknown, he was baptised in the church of St. Michael le Belfrey on 16 April and since the customary gap between birth and baptism was three days, he was probably born on 13 April.[3] Edith had given birth to a daughter named Anne a few years earlier, but the child died aged about seven weeks, in November 1568. She bore two more children in the years following Guy's birth: Anne (b. 1572), and Elizabeth (b. 1575). Both were married, in 1599 and 1594 respectively.[5][4]

Edward Fawkes died in 1579, aged about 46, when Guy was 8 years old. Edith remarried two or three years later, to the Catholic Dionis Baynbrigge (or Denis Bainbridge) of Scotton, Harrogate. Although the young Guy may have been influenced by the Baynbrigge family's recusant tendencies and also the Catholic branches of the Pulleyn and Percy families of Scotton,[6] the earliest Catholic influence on his life came during his time at St. Peter's School in York. The school had been governed by a man who had spent about 20 years in prison for recusancy, and its headmaster, John Pulleine, came from a family of noted Yorkshire recusants. Fawkes's fellow students included John Wright and his brother Christopher—both of whom were later involved with Fawkes in the Gunpowder plot—and Oswald Tesimond, Edward Oldcorne and Robert Middleton, who became priests (the latter executed in 1601).[7]

After leaving school at a young age, Fawkes became a footman for Anthony Browne, 1st Viscount Montagu. The Viscount took a dislike to Fawkes and after a short time dismissed him, however, he was subsequently employed as a waiter by Anthony-Maria Browne, 2nd Viscount Montagu, who succeeded his grandfather aged 18.[8]

As a soldier

In Continental Europe there had been a series of Wars of Religion stemming from a Protestant–Catholic issue in relation to the presumption of the French throne. England was divided, the English Protestant crown supported Navarre, while the Catholics of England supported the Catholic League and Pope Sixtus V, through the Duke of Guise.[9]

Sir William Stanley, a veteran soldier then in his mid-fifties, had raised an army in Ireland to fight in the Spanish Netherlands. Stanley had been held in high regard by Elizabeth I, but following his surrender to the Spanish in 1587, and his public conversion to Catholicism, he was viewed as a traitor. In 1592 Fawkes sold the estate in Clifton he had inherited from his father, and travelled to the Low Countries to join Stanley, fighting for Catholic Spain against the Protestant Dutch rebels. He became an alférez, fought well at the siege of Calais in 1596, and by 1603 was recommended for a captaincy.[10][11]

In 1603 he travelled with Anthony Dutton to Spain, to seek support for a Catholic rebellion in England. Fawkes also used the occasion to change his name, to Guido, and in his memorandum described James I as "a heretic", who intended "to have all of the Papist sect driven out of England." Fawkes also used the occasion to denounce Scotland, and the king's favouritism toward his Scottish nobles, writing "it will not be possible to reconcile these two nations, as they are, for very long".[12] Although they were received politely, the court of Philip III was unwilling to offer any support.[13]

Gunpowder Plot

Early stages

Fawkes's first meeting with Robert Catesby[nb 2] took place on Sunday 20 May 1604, at the Duck and Drake inn, in the fashionable Strand district of London. Catesby had already proposed at an earlier meeting with Thomas Wintour and Jack Wright to kill the King and his government by blowing up "the Parliament House with gunpowder". Wintour, who at first objected to the plan, was eventually convinced by Catesby to travel to the continent to seek help. Wintour met with the Constable of Castile, and also Hugh Owen and Sir William Stanley, who said that Catesby would receive no support from Spain. Owen did, however, introduce Wintour to Fawkes, who had by then been away from England for many years, and whose face was largely unknown there. Wintour and Fawkes were contemporaries; each was militant, and had first-hand experience of the unwillingness of the Spaniards to help. Wintour told Fawkes of their plan to "doe some whatt in Ingland if the pece with Spaine healped us nott",[11] and the two men thus returned to England late in April 1604, to give Catesby the bad news.[14]

Following the meeting in May, Fawkes and his four co-conspirators swore an oath of secrecy. By coincidence, and ignorant of the plot, Father John Gerard (a friend of Catesby's) was celebrating Mass in another room, and the five men subsequently received the Eucharist.[15] In June 1604 co-conspirator Thomas Percy was promoted, gaining access to a house in London which belonged to John Whynniard, Keeper of the King's Wardrobe. Fawkes was installed as a caretaker, where he began to use the pseudonym John Johnson, servant to Percy.[16] The building was occupied however, so the plotters hired Catesby's lodgings in Lambeth, on the opposite bank of the Thames, from which their stored gunpowder and other supplies could be conveniently rowed across each night.[17]

Delay

On 24 December it was announced that the re-opening of Parliament would be delayed until 3 October 1605. The contemporaneous account of the prosecution (taken from Thomas Wintour's confession)[18] claimed that during this delay the conspirators were digging a tunnel beneath Parliament, although this story may have been a government fabrication; no evidence for the existence of a tunnel was presented by the prosecution, and no trace of one has ever been found. Fawkes did not admit the existence of such a scheme until his fifth interrogation, but even then could not locate the tunnel. Logistically, the attempt would have proved extremely difficult, especially as none of the conspirators had any experience of mining.[19] If the story is true however, by December the building was empty and the conspirators were busy tunnelling from their rented house to the House of Lords. They ceased their efforts when, during tunnelling, they heard a noise from above. Fawkes was sent out to investigate, and returned with the welcome news that the then-tenant's widow was clearing out a nearby undercroft—which was directly beneath the House of Lords.[20][11]

The plotters purchased the lease to the room, which also belonged to John Whynniard. The Palace of Westminster in the early 17th century was a warren of buildings clustered around the medieval chambers, chapels, and halls that housed both Parliament and the various royal law courts. The old palace was easily accessible, and Whynniard's building was along a right-angle to the House of Lords, alongside a passageway which led directly to the River Thames. Undercrofts were common features at the time, and Whynniard's undercroft was directly beneath the first-floor House of Lords. Unused and filthy, it was considered an ideal hiding place for the gunpowder the plotters planned to store there.[21] According to Fawkes, 20 barrels of gunpowder were brought in at first, followed by 16 more on 20 July. The supply of gunpowder was theoretically controlled by the government, but it was easily obtained from illicit sources.[22][nb 3] On 28 July however, the ever-present threat of the plague again delayed the opening of Parliament, this time until Tuesday 5 November.[23]

Overseas

Fawkes travelled overseas, and informed Hugh Owen of the plotters' plans, in order to gain support from the continental powers once the king had been killed. At some point during this trip his name made its way into the files of Robert Cecil, 1st Earl of Salisbury, who employed a network of spies across Europe. One of these spies, Captain William Turner, may have been responsible; although his information usually amounted to no more than a vague pattern of invasion reports, and included nothing which regarded the Gunpowder Plot, on 21 April he told how Fawkes was to be brought to England by Tesimond, and introduced to "Mr Catesby" and "honourable friends of the nobility and others who would have arms and horses in readiness".[24] Turner's report did not, however, mention Fawkes' pseudonym in England, John Johnson.[25][11]

When Fawkes returned to England is uncertain, however he was certainly back in London by late August, because he and Wintour discovered that the gunpowder stored in the undercroft had decayed. More gunpowder was brought into the room, with firewood to conceal it.[26] The details of the plot were finalised in October, in a series of taverns across London and Daventry. Fawkes' role was to light the fuse and then escape across the Thames. Simultaneously, a revolt in the Midlands would help to ensure the capture of James's nine-year-old daughter, Princess Elizabeth, who was to be placed on the throne. Acts of regicide were frowned upon, and Fawkes would therefore head to the continent, where he would explain to Catholic powers such as Albert and Isabella[who?] his holy duty in killing the king and his retinue.[27]

Discovery

Catesby, who was struggling to finance the scheme, had meanwhile added more conspirators to their number.[11] A few were concerned about fellow Catholics who would have been present at Parliament during the opening.[28] On the evening of 26 October, Lord Monteagle received an anonymous letter warning him to stay away, and to "retyre youre self into yowre contee whence yow maye expect the event in safti for ... they shall receyve a terrible blowe this parleament".[29] Despite quickly becoming aware of the letter– informed by one of Monteagle's servants– they resolved to continue with their plans, as it appeared that it "was clearly thought to be a hoax".[30] Fawkes made a further check on the undercroft on 30 October, and reported that nothing had been disturbed.[31] The conspirators resolved to continue their plan,[11] but Monteagle had been made suspicious, however, and the letter was shown to King James. The king ordered Sir Thomas Knyvet to conduct a search of the cellars underneath Parliament, which he did in the early hours of 5 November. Fawkes had taken up his station late on the previous night, armed with a slow match and a watch, given to him by Percy "becaus he should knowe howe the time went away".[11] He was found leaving the cellar, shortly after midnight, and arrested. Inside, the barrels of gunpowder were discovered hidden under piles of firewood and coal.[32]

Torture and death

Fawkes gave his name as John Johnson and was first interrogated by members of the King's Privy Chamber, where he remained defiant. When asked by one of the lords what he was doing in possession of so much gunpowder, Fawkes answered, "To blow you Scotch beggars back to your native mountains."[33] He said only that he was a 36-year-old Catholic from Netherdale in Yorkshire, that his father was called Thomas, and his mother Edith Jackson. Wounds noticed on his body by his questioners he explained as the effects of pleurisy. A letter found on his person, addressed to Guy Fawkes, he claimed was to one of the aliases he used. He admitted intending to blow up the House of Lords, and expressed regret at his failure to do so. His steadfast manner earned him the admiration of King James, who described Fawkes as possessing "a Roman resolution".[34]

James's admiration for the man who had wanted to kill him did not, however, prevent him from ordering on 6 November that "John Johnson" be tortured, to reveal the names of his co-conspirators.[35] He directed that the torture be light at first, referring to the use of manacles, but more severe if necessary, authorising the use of the rack: "the gentler Tortures are to be first used unto him et sic per gradus ad ima tenditur".[36][33] Fawkes was transferred to the Tower of London. The King composed a list of questions to be put to "Johnson", such as "as to what he is, For I can never yet hear of any man that knows him", "When and where he learned to speak French?", and "If he was a Papist, who brought him up in it?".[37]

Sir William Wade, Lieutenant of the Tower of London, supervised the torture and obtained Fawkes's confession.[33] For several days Fawkes revealed nothing about the plot or his co-conspirators. On the night of 6 November he spoke with Sir William Waad, Lieutenant of the Tower, who reported to Salisbury "He [Johnson] told us that since he undertook this action he did every day pray to God he might perform that which might be for the advancement of the Catholic Faith and saving his own soul". "Johnson" explained his silence by referring to the oath he and the other plotters had sworn, followed by taking the Sacrament. According to Waad, Fawkes managed to rest through the night, although he was warned about what was to come. His composure was finally broken at some point during the following day.[38]

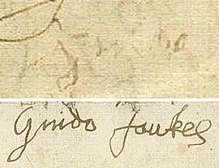

The observer Sir Edward Hoby remarked "Since Johnson's being in the Tower, he beginneth to speak English", referring to Fawkes's composure being broken. He revealed his true identity on 7 November, and told his interrogators that there were five (unnamed) people involved in the plot to kill the King. He began to reveal the names of those involved on 8 November, and told of how they intended to place Princess Elizabeth on the throne. His third confession, on 9 November, named Francis Tresham as one of those involved, and also Father Gerard as the priest who had administered the Sacrament following their oath, although Fawkes stressed that Gerard was ignorant of the plot. Although it is not certain if he was ever subjected to the horrors of the rack, Fawkes's signature, little more than a scrawl, bears testament to the suffering he endured at the hands of his interrogators.[39]

On 31 January, Fawkes and a number of others implicated in the conspiracy were tried in Westminster Hall. After being found guilty, they were taken to Old Palace Yard in Westminster and St Paul's Yard, where they were to be hanged, drawn and quartered. Fawkes, weakened by his torture, was the last to climb the ladder to the gallows, from which he jumped, breaking his neck in the fall and thus avoiding the latter part of his execution.[33]

Legacy

On 5 November 1605 Londoners were encouraged to celebrate the King's escape from assassination by lighting bonfires, "always provided that 'this testemonye of joy be careful done without any danger or disorder'".[11] The Lord Mayor and aldermen of the City of London commemorated the conspiracy on 5 November for years after with a sermon in St Paul's Cathedral. Popular accounts of the plot supplemented these sermons, some of which were published and have survived. Many in the city left money in their wills to pay for a minister to preach a sermon annually in their own parish.[citation needed]

Fawkes was described by the Jesuit priest and former school friend Oswald Tesimond as "pleasant of approach and cheerful of manner, opposed to quarrels and strife ... loyal to his friends". A soldier by profession, Tesimond also claimed Fawkes was "a man highly skilled in matters of war", and that it was this mixture of piety and professionalism which endeared him to his fellow conspirators.[11] Although he was only one of 13 conspirators, it is Fawkes with whom most people today associate the failed plot, and his effigy is ritually burnt on or around each 5 November. Similarly, associated rituals are still practised by the state; the vaults underneath the House of Lords are still searched on the eve of each Opening of Parliament.[40] In England, the date of 5 November has been variously called Guy Fawkes Night, Guy Fawkes Day and Bonfire Night, the latter derived from 5 November 1605.[41]

"Guy" came to mean a man of odd appearance. Subsequently, in American English, "guy" lost any pejorative connotation, becoming a simple reference for any man.[1]

According to the International Genealogical Index, compiled by the Mormon Church, Fawkes married Maria Pulleyn (b. 1569) in Scotton in 1590, and had a son, Thomas, on 6 February 1591.[42] These entries, however, appear to derive from a secondary source and not from actual parish entries, and no known contemporary accounts mention any such union.[43]

Many popular contemporary verses were written in condemnation of Fawkes. The most well-known verse begins:

Remember, remember the fifth of November,

Gunpowder, Treason and Plot.

I see no reason why Gunpowder Treason,

Should ever be forgot.[44]

John Rhodes produced a popular narrative in verse describing the events of the plot and condemning Fawkes:

Fawkes at midnight, and by torchlight there was found

With long matches and devices, underground

The full verse was published as A brief Summary of the Treason intended against King & State, when they should have been assembled in Parliament, 5 November. 1605. Fit for to instruct the simple and ignorant herein: that they not be seduced any longer by Papists. Other popular verses were of a more religious tone and celebrated the fact that England had been saved from the Guy Fawkes conspiracy. John Wilson published, in 1612, a short song on the "powder plot" with the words:

O England praise the name of God

That kept thee from this heavy rod!

But though this demon e'er be gone,

his evil now be ours upon!

The Fawkes story continued to be celebrated in poetry. The Latin verse In Quintum Novembris was written c. 1626. John Milton’s Satan in book six of Paradise Lost was inspired by Fawkes—the Devil invents gunpowder to try to match God's thunderbolts. Post-Reformation and anti–Catholic literature often personified Fawkes as the Devil in this way. From Puritan polemics to popular literature, all sought to associate Fawkes with the demonic. However, his reputation has since undergone a rehabilitation, and today he is often toasted as, "The last man to enter Parliament with honourable intentions." William Harrison Ainsworth's 1841 historical romance Guy Fawkes; or, The Gunpowder Treason, portrays Fawkes, and Catholic recusancy in general, in a sympathetic light and was one of the first accounts to challenge the official depiction of the plot.[45]

The public ranked Fawkes 30th in the BBC's 100 Greatest Britons,[46] and he was included in Sir Bernard Ingham's list of the 50 greatest people from Yorkshire.[47] The Guy Fawkes River and thus Guy Fawkes River National Park in northern New South Wales, Australia were named after Fawkes by explorer John Oxley, who, like Fawkes, was from North Yorkshire. In the Galápagos Islands a collection of two crescent-shaped islands and two small rocks northwest of Santa Cruz Island, are called Isla Guy Fawkes.[48]

References

- Notes

- ^ According to one source, however he may have been Registrar of the Exchequer Court of the Archbishop.[2]

- ^ Also present were fellow conspirators John Wright, Thomas Percy, and Thomas Wintour (whom he already knew).[14]

- ^ Gunpowder could be purchased on the black market from soldiers, militia, merchant vessels, and powdermills.[22]

- Footnotes

- ^ a b Merriam-Webster (1991), The Merriam-Webster new book of word histories, Springfield, MA: Merriam-Webster, p. 208, ISBN 0877796033, entry "guy"

- ^ Haynes 2005, pp. 28–29

- ^ a b Fraser 2005, p. 84

- ^ a b Sharpe 2005, p. 48

- ^ Fraser 2005, p. 86 (note)

- ^ Sharpe 2005, p. 49

- ^ Fraser 2005, pp. 84–85

- ^ Fraser 2005, pp. 85–86

- ^ Guy Fawkes: From York to the Battlefields of Flanders, Gunpowder-Plot.org, 24 October 2007

- ^ Fraser 2005, p. 87

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Nicholls, Mark (May 2009), "Fawkes, Guy (bap. 1570, d. 1606)" (Subscription required), Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.), oxforddnb.com, doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/9230, retrieved 6 May 2010

{{citation}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Fraser 2005, p. 89

- ^ Fraser 2005, pp. 88–90

- ^ a b Fraser 2005, pp. 117–119

- ^ Fraser 2005, p. 120

- ^ Fraser 2005, pp. 122–123

- ^ Haynes 2005, pp. 54–55

- ^ Nicholls, Mark (2004), "Winter, Thomas (c. 1571–1606)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (subscription required), Oxford University Press, doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/29767, retrieved 16 November 2009

{{citation}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Fraser 2005, pp. 133–134

- ^ Haynes 2005, pp. 55–59

- ^ Fraser 2005, pp. 144–145

- ^ a b Fraser 2005, pp. 146–147

- ^ Fraser 2005, pp. 159–162

- ^ Fraser 2005, p. 150

- ^ Fraser 2005, pp. 148–150

- ^ Fraser 2005, p. 170

- ^ Fraser 2005, pp. 178–179

- ^ Northcote Parkinson 1976, pp. 62–63

- ^ Northcote Parkinson 1976, pp. 68–69

- ^ Northcote Parkinson 1976, p. 72

- ^ Fraser 2005, p. 189

- ^ Northcote Parkinson 1976, p. 73

- ^ a b c d Northcote Parkinson 1976, pp. 91–92

- ^ Fraser 2005, pp. 208–209

- ^ Fraser 2005, p. 211

- ^ Fraser 2005, p. 215

- ^ Fraser 2005, p. 212

- ^ Fraser 2005, pp. 216–217

- ^ Fraser 2005, pp. 215–216, 228–229

- ^ Fraser 2005, p. 349

- ^ Fraser 2005, pp. 351–352

- ^ Herber, David, Britannia History, Guy Fawkes: A Biography

{{citation}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Fraser 2005, p. 86

- ^ "The Gunpowder Plot: Overview" Britannia.com. 24 April 2010

- ^ Harrison Ainsworth, William (1841), Guy Fawkes; or, The Gunpowder Treason, Nottingham Society

- ^ Top 100 Greatest Britons, biographyonline.net, 24 October 2007

{{citation}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Wainwright, Martin (24 October 2007), The 50 greatest Yorkshire people?, The Guardian, hosted at guardian.co.uk, retrieved 4 May 2010

{{citation}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=and|date=(help); Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Topography and Landforms of Ecuador (PDF), Geology.er.usgs.gov, 24 October 2007

- Bibliography

- Haynes, Alan (2005) [1994], The Gunpowder Plot: Faith in Rebellion, Sparkford, England: Hayes and Sutton, ISBN 0750942150

- Fraser, Antonia (2005) [1996], The Gunpowder Plot, London: Phoenix, ISBN 0753814013

- Northcote Parkinson, C. (1976), Gunpowder Treason and Plot, Weidenfeld and Nicolson, ISBN 0-297-77224-4

- Sharpe, J. A. (2005), Remember, remember: a cultural history of Guy Fawkes Day (illustrated ed.), Harvard University Press, ISBN 0674019350

External links

- York Guy Fawkes Trail, a pdf of a walking trail in York.

- Guy Fawkes page on History of York website

- A biography of Guy Fawkes from the Gunpowder Plot Society

- Guy Fawkes and Bonfire Night at bonfirenight.net

- Guy Fawkes and the Gunpowder Plot at allinfoaboutenglishculture.com

- 1570 births

- 1606 deaths

- English criminals

- English rebels

- English Roman Catholics

- Executed English people

- Executed Gunpowder Plotters

- Failed assassins

- History of Roman Catholicism in England

- Old Peterites

- People executed by hanging, drawing and quartering

- People executed under the Stuarts

- People from York

- Roman Catholic activists

- Prisoners in the Tower of London