Juan Manuel de Rosas: Difference between revisions

Cambalachero (talk | contribs) |

Cambalachero (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 134: | Line 134: | ||

{{section-stub}} |

{{section-stub}} |

||

After the victory of Oribe at Arroyo Grande, the ambassadors of Britain and France, Mandeville and De Lurde, threatened Rosas to retreat from Uruguayan territory. Rosas did not reply, and ordered Brown to support Oribe by making a naval blockade on Montevideo. The British comodor [[John Brett Purvis]] attacked the Argentine navy, saying that the new American countries were not maritime powers authorized to make blockades. Mandeville and De Lurde were replaced by Ousley and Deffaudis. [[Florencio Varela (writer)|Florencio Varela]] made a diplomatic journey to Europe, seeking support for a British intervention against Rosas or, if the British accepted so, an Anglo-French attach. He also proposed to turn the [[Mesopotamia, Argentina|Argentine Mesopotamia]] into an independent country, under British protection. As a result, the Uruguay and Parana rivers would not be [[internal waters]] anymore, and would be beyond Argentine sovereignthy. J.Ellauri, Uruguayan ambassador in France, manifested as well his interest in the creation of such a state and to make treaties with it, Paraguay and Brazil. |

After the victory of Oribe at Arroyo Grande, the ambassadors of Britain and France, Mandeville and De Lurde, threatened Rosas to retreat from Uruguayan territory. Rosas did not reply, and ordered Brown to support Oribe by making a naval blockade on Montevideo. The British comodor [[John Brett Purvis]] attacked the Argentine navy, saying that the new American countries were not maritime powers authorized to make blockades. Mandeville and De Lurde were replaced by Ousley and Deffaudis. [[Florencio Varela (writer)|Florencio Varela]] made a diplomatic journey to Europe, seeking support for a British intervention against Rosas or, if the British accepted so, an Anglo-French attach. He also proposed to turn the [[Mesopotamia, Argentina|Argentine Mesopotamia]] into an independent country, under British protection. As a result, the Uruguay and Parana rivers would not be [[internal waters]] anymore, and would be beyond Argentine sovereignthy. J.Ellauri, Uruguayan ambassador in France, manifested as well his interest in the creation of such a state and to make treaties with it, Paraguay and Brazil. |

||

The European powers needed a convincing argument to justify before their own populations why to declare the war. For this end, Florencio Varela requested to the former federal [[José Rivera Indarte]] to write a list of crimes that Rosas could be blamed for. The French firm Lafone & Co paid him with a penny for each death listed. The list, named as ''[[Blood tables]]'', included deaths caused by military actions of the unitarians (including Lavalle's invasion of Buenos Aires), soldiers shot during wartime because of mutiny, treason or espionage, victims of common crimes and even people that was still alive. He also listed [[Nomen nescio|NN]] deaths (unidentified people), and some entries were listed more than once. He also blamed him for the death of [[Facundo Quiroga]]. With all this, Indarte listed 480 deaths, and was paid with two [[Pound sterling]] (U$S 8.400 in modern prices). He tried to add to the list 22.560 deaths, the number of deaths caused by military conflicts in Argentina from 1829 to that date, but the French refused to pay for them. Indarte wrote in his libel that "it is a holy action to kill Rosas". Lafone & Co, who paid for the Blood tables, had the control of the Uruguayan customs, and would be highly benefited from a new blockade on Buenos Aires. |

|||

===Decline and fall=== |

===Decline and fall=== |

||

Revision as of 02:38, 25 November 2010

Juan Manuel de Rosas | |

|---|---|

| |

| 17th Governor of Buenos Aires Province | |

| In office March 7, 1835 – February, 3 1852 | |

| Preceded by | Manuel Vicente Maza |

| Succeeded by | Vicente López y Planes |

| 13th Governor of Buenos Aires Province | |

| In office December 8, 1829 – December 17, 1832 | |

| Preceded by | Juan José Viamonte |

| Succeeded by | Juan Ramón Balcarce |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Juan Manuel José Domingo Ortiz de Rozas y López de Osornio March 30, 1793 Buenos Aires, Argentina |

| Died | March 14, 1877 (aged 83) Southampton, United Kingdom |

| Nationality | Argentina |

| Political party | Federal Party |

| Spouse | Encarnación Ezcurra |

| Signature |  |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata, Argentine Confederation |

| Rank | Brigadier |

| Unit | Regiment of Migueletes |

| Commands | Militias of Buenos Aires |

| Battles/wars | British invasions of the Rio de la Plata, Battle of Márquez Bridge |

Juan Manuel de Rosas (born Juan Manuel José Domingo Ortiz de Rozas y López de Osornio; March 30, 1793 – March 14, 1877), was a conservative Argentine politician who governed the Buenos Aires Province from 1829 to 1832 and from 1835 to 1852. Rosas was one of the first famous caudillos in Ibero-America and through his rule united Argentina, provided an efficient government and strengthened the economy. Besides being governor, Rosas managed the foreign relations of the Argentine Confederation, which lacked a formal head of state. Rosas endured seven wars undefeated and without any territorial losses to the Confederation. He was forced to resign after his defeat at the Battle of Caseros against an army gathered by Justo José de Urquiza.

Biography

Early life

He was the son of León Ortiz de Rosas y de la Cuadra and wife Agustina Teresa López de Osornio. Born to one of the wealthiest families in the Río de la Plata region, Rosas ran away from home at a young age and began working in the fields of his cousins Juan José and Nicolás Anchorena. He modified his last name from "Rozas" to "Rosas" and removed the "Ortiz" part of it. At the age of 13, he fought during the British invasions of the Rio de la Plata, joining the forces led by Santiago de Liniers that drove the British out of Buenos Aires.[1] He also fought during the second ill-fated British invasion, joining the Regiment of Migueletes.

After that, he resumed his work in the fields, working as an "arriero", carrying cattle through the immensities of the pampas. He created a society with Juan Nepomuceno Terrero and Luis Dorrego (brother of Manuel Dorrego) when he was twenty-two, and the business immediately flourished. He married right before age 20 on March 16, 1813 to the almost 18-year-old María de la Encarnación de Ezcurra y Arguibel and they had one child, a daughter Manuela Robustiana de Rosas y Ezcurra, born in Buenos Aires on May 24, 1817. Manuela would marry years later with the son of Juan Terrero. Rosas' business were benefited when the Supreme Director Juan Martín de Pueyrredón ordered the closing of salt-meat plants, which allowed him to buy 300.000 hectares of land.

He combined a strict discipline with the gauchos under his command with a conduct of sharing their uses and customs, and subjecting himself to the same discipline he demanded from them. Outlaws like thiefs, deserters or fugitive slaves were welcomed in his lands and protected from outside retaliation, as long as they worked as the others. The territories of Rosas were next to those of the pampas, tehuelches and ranqueles, so his gauchos were organized as a military force to resist malones.

Rosas joins the Civil War

In 1820, during the Brazilian invasion of the Banda Oriental, provincial caudillos Estanislao López and Francisco Ramírez joined forces and advanced to Buenos Aires. The Supreme Director José Rondeau requested José de San Martín and Manuel Belgrano to return to Buenos Aires with the Army of the Andes and the Army of the North, but San Martín stayed in Peru to keep fighting against the Royalists and the Army of the North mutinied to avoid joining the Argentine Civil War. Buenos Aires had weak local defenses, which were defeated during the battle of Cepeda. The authority of the Supreme Directors was terminated.

Ranchers feared that the ongoing events would lead to anarchy, and organized a regiment of gauchos to face the situation. Rosas was trusted to lead them. He promoted the designation of Martín Rodríguez as governor of Buenos Aires, and negotiated with López his return to Santa Fe in exchange of 25.000 cattle. This started a strong relation between Rosas and López, that would be kept for years.

Years later, Bernardino Rivadavia resigned as president of Argentina, incapable of securing the military victory in the Argentina-Brazil War, and Manuel Dorrego was chosen as governor of Buenos Aires. Under his rule, Rosas would be promoted to commander of the militias of Buenos Aires. However, the armies returning from Brazil would turn against Dorrego, and Juan Lavalle would execute him and conduct a coup to take the government of Buenos Aires. The unitarians would start a reign of terror, aiming to destroy all Federals. In 1829 the demographic growth was negative, as there were more deaths than births. During that time, José de San Martín had returned from Europe, but disgusted with the new political situation, he refused to leave the ship and returned back to Europe.

The other provinces did not recognize Lavalle as a legitimate governor, and supported the Rosist resistance instead. Lavalle would be defeated a short time later at the Battle of Márquez Bridge by the forces of Rosas and López. López returned to Santa Fe, which was menaced by José María Paz, while Rosas kept Lavalle under siege and forced him to resign with the Cañuelas pact. Juan José Viamonte was designated as governor, and the legislature removed during Lavalle's revolution was restored. This legislature would elect Rosas as governor.

First government

As a governor, Rosas applied a strong and strict authority. He considered that, given the social disgregation of the Argentine Confederation by that time, it was the only way to keep it toguether and prevent anarchy.

The King can be compared with a father, and reciprocally a father can be compared with the King, and then set the duties of the monarch by those of the parental authorithy. Love, govern, reward and punish is what a King and a father must do. In the end, there's nothing less legitimate than anarchy, which removes property and security from the people, as force becomes then the only right.

Rosas faced opposition from the unitarian provinces in the north. José María Paz, after defeating Facundo Quiroga at the battle of Tablada, took control of the Cordoba province and started a reign of terror to destroy all federal in the zone, similar to the one started by Lavalle in Buenos Aires. The newspaper "La Gaceta" would number the victims of the unitarian terror in 2.500 victims. Paz expanded his influence by creating the Unitarian League, while Rosas created the Federal Pact instead. The plans of Paz would fail when his horse was taken down and he was captured. Federalist José Vicente Reinafé, close to López, would replace him as governor of Córdoba. Córdoba, Santiago del Estero, La Rioja and the provinces of Cuyo would join the Federal Pact in 1831, Catamarca, Tucumán and Salta would do so the following year. As for Paz himself, he was held captive by Estanislao López, but he refused to execute him. He requested Rosas to check that it was the will of all the provinces to execute Paz, but Rosas did not accept the request. He considered that the fate of Paz should be decided solely by López, who had him prisoner.

One of the keys of the economic supremacy of Buenos Aires was its monopoly over the port and customs of Buenos Aires, the only one linking the Confederation with Europe. Rosas refused to lift the control over it, considering that Buenos Aires was facing alone the international debt generated by the Argentine War of Independence and the Argentina-Brazil War.

The defeat of Paz and the expansion of the Federal Pact further ushered in a period of economic and political stability. As a result, Federalists were divided between two political trends: those who wanted the calling of a Constituent Assembly to write a Constitution, and those who supported Rosas in delaying it. Rosas thought that the best way to organize the Argentine Confederation was as a federation of federated states, similar to the successful States of the United States; each one should write its own local constitution and organize itself, and a national constitution should be written at the end, without being rushed.

He had a successful and popular first term, but refused to run for a second one even though public support was strong.[2]

First Conquest of the Desert

After his resignation as governor, Rosas left Buenos Aires and started the first Conquest of the Desert, to expand and secure the farming territories and prevent indigenous attacks. Rosas was aware that malones were not done because of evil desires but because of the lacking lyfestyle condition of the indigenous peoples. As a result, he had preference for a policy of doing pacts or giving gifts or bribes to the caciques before employing military force. The hostile ranquel cacique Yanquetruz was replaced by Payné, who allied with Rosas. Juan Manuel, in turn, adopted his son and raised him at his estancia. The pehuenche Cafulcurá was condecorated as colonel and allowed to distribute large numbers of gifts among his people; in turn, he made the compromise of not making any more malones. On the other hand, caciques like the pehuenche Chocorí who defied Rosas were defeated.

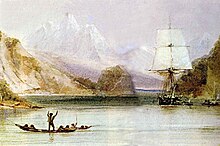

Charles Darwin met Rosas in 1830, and wrote about it in The Voyage of the Beagle. He was at Carmen de Patagones and knew that Rosas was located nearby, close to the Colorado River. He had heard about him from before, so he moved to meet him. He described him as a man of extraordinary character, a perfect horseman who conformed to the dress and habits of the Gauchos and "has a most predominant influence in the country, which it seems he will use to its prosperity and advancement".[3] Darwin included a story of how Rosas had himself put in the stocks for inadvertently breaking his own rule of not wearing knives on Sundays. This appealed to his men's sense of egalitarianism and justice. Darwin also described an anecdote about a pair of buffoons.

By the end of the first Conquest of the Desert, Buenos Aires increased its lands by thousands of square kilometers, which were distributed among new and older hacendados. The natives did not make any more malones, accepted to provide military aid to Rosas in case of need, and stayed in peaceful terms for all the reminder of Rosas' government.

Even being absent, the political influence of Rosas in Buenos Aires was still strong, and his wife Encarnación Ezcurra was in charge of keeping good relations with the peoples of the city. On October 11, 1833, the city was filled with announcements of a trial against Rosas. A large number of gauchos and poor people made the Revolution of the Restorers, a demonstration at the gates of the legislature, praising Rosas and demanding the resignation of governor Juan Ramón Balcarce. The troops organized to fight the demonstration mutinied and joined it. The legislature finally gave up the trial, and a month later ousted Balcarce and replaced him with Juan José Viamonte. The Revolution also led to the creation of the Sociedad Popular Restauradora, also known as "Mazorca".

Second government

The weak governments of Balcarce and Viamonte led the legislature to request Rosas to take the government once more. For doing so he requsted the sum of public power, which the legislature denied four times. Rosas even resigned as commander of militias to influence the legislature. The context changed with the social commotion generated by the death of Facundo Quiroga, responsibility for which is disputed (different authors attribute it to Estanislao López, the Reinafé brothers, or Rosas himself). The legislature accepted then to give him the sum of public power. Even so, Rosas requested confirmation on whenever the people agreed with it, so the legislature organized a referendum about it. Every free man within the age of majority living in the city was allowed to vote for "Yes" or "No": 9.316 votes supported the release of the sum of public power on Rosas, and only 4 rejected it. There are divided opinions on the topic: Domingo Faustino Sarmiento compared Rosas with historical dictators, while José de San Martín considered that the situation in the country was so chaotic that a strong authority was needed to create order.

Although slavery was not abolished during Rosas' rule, Afro Argentines had a positive image of him. He allowed them to gather in groups related to their African origin, and financed their activities. Troop formations included many of them, because joining the army was one of the ways to become a free negro, and in many cases slave owners were forced to release them to strengthen the armies. There was an army made specifically of free negros, the "Fourth Batallion of Active Militia". The liberal policy towards slaves generated controversy with neighbouring Brazil, because fugitive Brazilian slaves saw Argentina as a safe haven: they were recognized as free men at the moment they crossed the Argentine borders, and by joining the armies they were protected from persecution of their former masters.

The people who opposed Rosas formed a group called Asociacion de Mayo or May Brotherhood. It was a literary group that became politically active and aimed at exposing Rosas' actions. Some of the literature against him includes The Slaughter House, Socialist Dogma, Amalia and Facundo. Meetings which had high attendance at first soon had few members attending out of fear of prosecution. Rosas' opponents during his rule were dissidents, such as José María Paz, Salvador M. del Carril, Juan Bautista Alberdi, Esteban Echeverria, Bartolomé Mitre and Domingo Faustino Sarmiento.[2] Rosas political opponents were exiled to other countries, such as Uruguay and Chile.

First French blockade

The Peru–Bolivian Confederation declared the War of the Confederation against Argentina and Chile. His protector Andrés de Santa Cruz supported the European interests in South America, as well as the Unitarians, whereas Rosas and the Chilean Diego Portales did not. As a result, France gave full support to Santa Cruz in this war. Britain also supported Santa Cruz, but only by diplomatic meanings. Trusting in the military power at his disposal, Santa Cruz declared war against both countries at the same time. Initially, the Peru-Bolivian forces had the advantage, and captured and executed Portales. The war did not develop favorably for Argentina in the north, and the French Roger moved to Buenos Aires to request the surrender of Argentina. He demanded that a pair of French citizens be released from prison, that another pair be exempted from military service, and that France receive the same commercial privileges granted by Bernardino Rivadavia to Britain. Although the requests were light, Rosas considered that they would only set a precedent for further French interferences in the internal affairs of Argentina, and refused to comply. As a result, France started a naval blockade against Buenos Aires.

Rosas took advantage of the British interests in the zone. The minister Manuel Moreno pointed out to the Foreign Office that the commerce between Argentina and Britain was being harmed by the French blockade, and that it would be a mistake for Britain to support it. The French judged that the people would seize the opportunity to stand against Rosas, but underestimated his popularity. With the nation being threatened by two European powers as well as two neighbour countries allied with them, internal patriotic loyalty increased to the point that even some notable Unitarians who had fled to Montevideo returned to the country to offer their military help, such as Soler, Lamadrid and Espinosa. Things became more complicated for France as time passed: Andrés Santa Cruz was weakening, the strategy employed by Moreno was bearing fruit, and the French themselves started to doubt about keeping up a conflict that they had counted on to be quite short. Also, Britain would not allow the French to deploy troops, as they did not want a European competitor gaining territorial strength in the zone. Domingo Cullen, governor of Santa Fe replacing the ill López, considered that Rosas had nationalized a conflict that involved just Buenos Aires, and proposed to the French that they should cause Santa Fe, Córdoba, Entre Ríos and Corrientes to secede, creating a new country that would obey them, if this new country would be spared the naval blockade. Also, Manuel Oribe, president of Uruguay and allied with Rosas, was ousted by Fructuoso Rivera with French aid. France wanted Rivera and Cullen to join forces and take Buenos Aires, while their ships kept the blockade. This alliance did not take place, as Juan Pablo López, brother of Estanislao López, defeated Cullen and drove him away from the province. Also, Andrés Santa Cruz was defeated by Chile in the Battle of Yungay, and the Peru–Bolivian Confederation ceased to exist. Now Rosas was free to focus all his attention towards the French blockade.

His wife Encarnación died in Buenos Aires on October 20, 1838.

Rivera was urged by France to take military action against Rosas, but he was reluctant to do so, considering that the French underestimated his strength, even more after Santa Cruz's defeat. As a result, they elected Juan Lavalle to lead the attack, who requested not to share command with Rivera. As a result, they led both their own armies. His imminent attack was backed up by conspiracies in Buenos Aires, which were discovered and aborted by the Mazorca. Manuel Vicente Maza and his son were among the perpetrators, and were executed as a result. Pedro Castelli also organized an ill-fated demonstration against Rosas, and was executed as well. Rosas did not wait to be attacked, and ordered Pascual Echagüe to cross the Parana and move the fight to Uruguay. The Uruguayan armies split: Rivera returns to defend Montevideo, and Lavalle moves to Entre Ríos alone. He expectd that local populations would join him against Rosas and increase his forces, but he found severe resistance, so he moved to Corrientes. Ferré defeated López, and Rivera defeated Echagüe, leaving Lavalle a clear path towards Buenos Aires. However, by that point France had given up the trust on the effectiveness of the blockade, as what was thought to be an easy and short conflict was turning into a long war, without clear security of a final victory. France started to negotiate peace with the Confederation and removed financial support to Lavalle. He didn't find help at local towns either, and there was strong desertion in his ranks. Buenos Aires was ready to resist his military attack, but the lack of support forced him to give it up and retire from the battlefield, without starting any battle.

The civil war continues

The unitarians and colorados kept their hostilities against Rosas, even after the defeat of France. The new pan was that ferré and Rivera, at Corrientes and Uruguay, would create a new army, while Lavalle and Lamadrid moved to the north. Lavalle would move to La Rioja and distract the Federal armies, while Lamadrid organized another army at Tucumán. By this time José María Paz escaped from his imprisonment. Rosas spared his life because he had sworn never to attack the Confederation again, but he broke his oath. His presence benefited the antirosist forces, but also generated internal stir: Ferré gave him the command of the armies of Corrientes, which Rivera did not like. Rivera even accused Paz of being a spy of Rosas. Nevertheless, the combined forces of Paz, Rivera and unitarian ships at the river had the federal forces of Echague at Santa Fe surrounded. To counter the unitarian naval supremacy, Guillermo Brown organized a ship squad that would defeat captain Coe at Santa Lucía.

Oribe defeated the forces of Lavalle at La Rioja, but Lavalle himself managed to escape to Tucuman. Lamadrid attacked San Juan, but was completely defeated. Oribed defeated Lavalle at Tucuman, who barely escaped with a group of 200 men to the north. Lavalle died shortly after, in a confusing episode. The ended the antirosist threat at the Argentine northwest.

Rivera threatened Ferré to end their alliance if he insisted in favoring Paz. Rivera wanted to anex the Riograndense Republic (part of Rio Grande do Sul, that had declared independence from Brazil and was fighting the War of the Farrapos) and the Argentine mesopotamia into a projected Federation of Uruguay, but Paz was against that project. Paz defeated Echague, and Rivera defeated the new federal governor of Entre Ríos, Justo José de Urquiza. Even more, federal Juan Pablo López from Santa Fe changed sides to the unitarian ranks.

Rosas was again at a weak position, and wouldn't had been able to resist an attack by that point. But Paz, Ferré, Rivera and López had conflicting battle plans, and their armies did not move, which gave Oribe time to return from the north. The forces of Santa Fe refused to figth for the unitarians, and a massive defection reduced López armies from 2.500 men to just 500. He was easily defeated at Coronda and Paso Aguirre. Ferré was finally interested in Rivera's federation, and putted Paz aside. Rivera and Oribe, both ones considering themselves rightful presidents of Uruguay, would battle. The battle of Arroyo Grande was a decisive victory of Oribe, and Rivera barely escaped alive. Thus, the unitarian threat to Rosas was removed once more.

Anglo-French blockade

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. |

After the victory of Oribe at Arroyo Grande, the ambassadors of Britain and France, Mandeville and De Lurde, threatened Rosas to retreat from Uruguayan territory. Rosas did not reply, and ordered Brown to support Oribe by making a naval blockade on Montevideo. The British comodor John Brett Purvis attacked the Argentine navy, saying that the new American countries were not maritime powers authorized to make blockades. Mandeville and De Lurde were replaced by Ousley and Deffaudis. Florencio Varela made a diplomatic journey to Europe, seeking support for a British intervention against Rosas or, if the British accepted so, an Anglo-French attach. He also proposed to turn the Argentine Mesopotamia into an independent country, under British protection. As a result, the Uruguay and Parana rivers would not be internal waters anymore, and would be beyond Argentine sovereignthy. J.Ellauri, Uruguayan ambassador in France, manifested as well his interest in the creation of such a state and to make treaties with it, Paraguay and Brazil.

The European powers needed a convincing argument to justify before their own populations why to declare the war. For this end, Florencio Varela requested to the former federal José Rivera Indarte to write a list of crimes that Rosas could be blamed for. The French firm Lafone & Co paid him with a penny for each death listed. The list, named as Blood tables, included deaths caused by military actions of the unitarians (including Lavalle's invasion of Buenos Aires), soldiers shot during wartime because of mutiny, treason or espionage, victims of common crimes and even people that was still alive. He also listed NN deaths (unidentified people), and some entries were listed more than once. He also blamed him for the death of Facundo Quiroga. With all this, Indarte listed 480 deaths, and was paid with two Pound sterling (U$S 8.400 in modern prices). He tried to add to the list 22.560 deaths, the number of deaths caused by military conflicts in Argentina from 1829 to that date, but the French refused to pay for them. Indarte wrote in his libel that "it is a holy action to kill Rosas". Lafone & Co, who paid for the Blood tables, had the control of the Uruguayan customs, and would be highly benefited from a new blockade on Buenos Aires.

Decline and fall

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. |

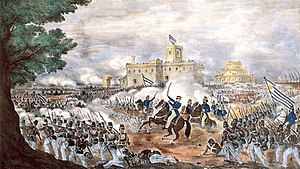

General Urquiza, who was governor of the Entre Ríos Province and once backed Rosas, organized an army against him. Other provinces as well as Brazil and Uruguay joined the fight to take down the dictator.[2] On February 3, 1852, Rosas was overthrown when his army was defeated at the Battle of Caseros. After Caseros battle Rosas spent the rest of his life in exile, in the United Kingdom, as a farmer in Southampton. He was initially buried in the Southampton Old Cemetery in Southampton Common until his body was exhumed in 1989 and transferred to the La Recoleta Cemetery in Argentina.

Rosas received the 'combat sable' from General San Martin, 'maximum hero' of Argentina, who judged that Rosas was the only man capable of defending Argentina against the European powers, especially the British.

Criticism and historical perspective

The figure of Juan Manuel de Rosas and his government generated strong conflicting viewpoints, both in his own time and afterwards.

In the context of the Argentine Civil War, Rosas was the main leader of the Federalist party, and as such the most part of the controversies around him were motivated by the preexistent antagonism of Federalism with the Unitarian Party. During the government of Rosas most unitarians fled to neighbour countries, mostly to Chile, Uruguay and Brazil; among them we can find Domingo Faustino Sarmiento, who wrote Facundo while living in Chile. Facundo is a critic biography of Facundo Quiroga, another federalist caudillo, but Sarmiento used it to pass many indirect or direct critics to Rosas himself. Some members of the 1837 generation, such as Esteban Echeverría or Juan Bautista Alberdi, tried to generate an alternative to the unitarians-federalists antagonism, but had to flee to other countries as well.

After the defeat of Rosas in Caseros and the return of his political adversaries, it was decided to portray him in a negative light. The legislature of Buenos Aires charged him with High treason in 1857; Nicanor Arbarellos supported his vote with the following speech:

Rosas, sir, that tyrant, that barbarian, even if barbarian and cruel, was not considered as such by the European and civilized nations, and that judgement of the European and civilized nations, moved to posterity, will hold in doubt, at least, that barbarian and execrable tyrany that Rosas exercised among us. It's needed, then, to mark with a legislative sanction declaring him guilty of lèse majesté so at least this point is marked in history, and it is seen that the most potent court, which is the popular court, which is the voice of the sovereign peoples by us represented, throws to the monster the anathema calling him traitor and guilty of lèse majesté. Judgements like those must not be left for history.

What will be said, what might be said in history when it's seen that the civilized nations of the world, for whom we are but just a point, have acknowledged in this tyrant a being worthy to deal with them? That England has returned his cannons taken in war action, and saluted his bloody and innoent-blood stained flag with a 21-gun salute? This fact, known by history, would be a great counterweight, sir, if we leave Rosas without this sanction. The France itself, which started the crusade that was shared by general Lavalle, in its due time also abandoned him, dealed with Rosas and saluted his flag with a 21-gun salute. I ask, sir, if this fact won't erase from history everything we may say, if we leave this monster that decimated us for so many years without a sanction.

The judgement of Rosas must not be left to history, as some people desire. It's clear that it can't be left to history the judgement of the tyrant Rosas. Let's throw to Rosas this anathema, which perhaps can be the only one to harm him in history, because otherwise his tyrany will always be doubtful, as well as his crimes! What will be said in history, sir?, and this is sad to tell, what will be said in history when it is said that the brave Admiral Brown, the hero of the Navy of the Independence war, was the admiral who defended the tyranny of Rosas? What will be said in history without this anathema, when it is said that this man who contributed with his glories and talents to give shine to the Sun of May, that the other deputee referenced in his speech, when it is said that General San Martín, the conqueror of the Andes, the father of the Argentine glories, made him the greatest tribute that can be given to a soldier by handing him his sword? Will this be believed, sir, if we don't throw an anathema to the tyrant Rosas? Will this man be known as he is in 20 or 50 years, if we want to go further, when it is known that Brown and San Martín were loyal to him and gave him the most respectful tributes, along with France and England?

No, sir: they will say, the savage unitarians, his enemies, lied. He has not been a tyrant: far from that, he has been a great man, a great general. It's needed to throw without dobts this anathema to the monster. If at least we had imititated the English people, who draged the corpse of Cromwell across the streets of London, and had draged Rosas across the streets of Buenos Aires! I support, mr. president, the project. If the judgement of Rosas was left to the judgement of history, we won't get Rosas to be condemned as a tyrant, but perhaps he may be in it the greatest and most glorious of Argentines.[4]

The first historians of Argentina, such as Bartolomé Mitre, were vocal critics of Rosas, and for many years there was a clear consensus in condemning him. However, authors like Mitre or Sarmiento can't be considered exclusiely from the perspectives of historiography or the history of ideas, as they were active people and even protagonists of the political struggles of their time; and their works were used as tools to advertise their political ideas.[5] Adolfo Saldías was the first in not condemning Rosas entirely, and in the book Historia de la Confederación Argentina he supported his international policy, while keeping the usual rejection on the treatment given by Rosas to detractors. Authors like Levene, Molinari or Ravignani, in the 1930 decade, would develop a neutral approach to Rosas, that Ravignani defined as "Nor with Rosas, nor against Rosas".[6] Their work would be more oriented towards the positive things of the early years of Rosas, and less into the most polemic ones.[6]

Years later, a new historiographical flow made an active and strong support of Rosas and other caudillos. Because of its great differences with the early historians the local historiography knows them as revisionists, while the early one is named "official" or "academic" instead. However, despite namings, the early historiography of Argentina hasn't always followed standard academic procedures, nor developed hegemonic views at all topics.[7] They would expand the work of Saldías and Ernesto Quesada, and developed instead negative views about Mitre, Sarmiento, Rivadavia and the unitarians.

Modern historians like Felipe Pigna or Félix Luna avoid joining the dispute, describing instead the existence of conflicting viewpoints towards Rosas. The historiographical dispute about Rosas is currently considered to be over.[8][9]

Legacy

The date of November 20, anniversary of the battle of Vuelta de Obligado, has been declared "Day of National Sovereignty" of Argentina, following a request by revisionist historian José María Rosa.[10][11] This observance day was raised in 2010 to a public holiday by Cristina Fernández de Kirchner.[12] Rosas has been included in the banknotes of 20 Argentine pesos, with his face and his daughter Manuela Rosas in the front and a depiction of the battle of Vuelta de Obligado in the back. A monument of Rosas, 15 meters tall and with a weight of 3 tons, has been erected in 1999 in the city of Buenos Aires, at the conjunction of the "Libertador" and "Sarmiento" avenues.[13]

The aforementioned law that charged Rosas of high treason was derogated in the 1970 decade.

A portrait of Rosas was included in 2010 in a gallery of Latin American patriots, held at the Casa Rosada. The gallery, which included works provided by the presidents of other Latin American countries, was held because of the 2010 Argentina Bicentennial.[14]

See also

Bibliography

- Luna, Félix (2003). La época de Rosas. Buenos Aires: Grupo Editorial Planeta. ISBN 950-49-1116-1.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Mendelevich, Pablo (2010). El Final. Buenos Aires: Ediciones B. ISBN 978-987-627-166-0.

- Argentine Caudillo: Juan Manuel de Rosas, by John Lynch (1981, 2001).

- Crow, John A. The Epic of Latin America. New York: University of California P, 1992.

- "Juan Manuel de Rosas." Britannica. 2008. 25 Oct. 2008.

References

- ^ Secretos de la última invasión inglesa Template:Es

- ^ a b c Crow

- ^ Chapter IV: Rio Negro To Bahía Blanca

- ^ Rosa, José María. Historia Argentina, V. Buenos Aires. p. 491.

Spanish: Rosas, señor, ese tirano, ese bárbaro, así bárbaro y cruel, no era considerado lo mismo por las naciones europeas y civilizadas, y ese juicio de las naciones europeas y civilizadas, pasando a la posteridad, pondrá en duda, cuando menos, esa tiranía bárbara y execrable que Rosas ejerció entre nosotros. Es necesario, pues, marcar con una sanción legislativa declarándole reo de lesa patria para que siquiera quede marcado este punto en la historia, y se vea que el tribunal más potente, que es el tribunal popular, que es la voz del pueblo soberano por nosotros representado, lanza al monstruo el anatema llamándole traidor y reo de lesa patria... Juicios como éstos no deben dejarse a la historia... ¿Qué se dirá, qué se podrá decir en la historia cuando se viere que las naciones civilizadas del mundo, para quien nosotros somos un punto... han reconocido en ese tirano un ser digno de tratar con ellos?, ¿que la Inglaterra le ha devuelto sus cañones tomados en acción de guerra, y saludado su pabellón sangriento y manchado con sangre inocente con la salva de 21 cañonazos?... Este hecho conocido en la historia, sería un gran contrapeso, señor, si dejamos a Rosas sin este fallo. La Francia misma, que inició la cruzada en que figuraba el general Lavalle, a su tiempo también lo abandonó, trató con Rosas y saludó su pabellón con 21 cañonazos... Yo pregunto, señor, si este hecho no borrará en la historia todo lo que podamos decir, si dejamos sin un fallo a este monstruo que nos ha diezmado por tantos años... No se puede librar el juicio de Rosas a la historia, como quieren algunos... Es evidente que no puede librarse a la historia el fallo del tirano Rosas... ¡Lancemos sobre Rosas este anatema, que tal vez sea el único que puede hacerle mal en la historia, porque de otro modo ha de ser dudosa siempre su tiranía y también sus crímenes... ¿Qué se dirá en la historia, señor?, y esto sí que es hasta triste decirlo, ¿qué se dirá en la historia cuando se diga que el valiente general Brown, el héroe de la marina en la guerra de la independencia, era el almirante que defendió los derechos de Rosas? ¿Qué se dirá en la historia sin este anatema, cuando se diga que este hombre que contribuyó con sus glorias y talentos a dar brillo a ese sol de Mayo, que el señor diputado recordaba en su discurso, cuando se diga que el general San Martín, el vencedor de los Andes, el padre de las glorias argentinas, le hizo el homenaje más grandioso que puede hacer un militar legándole su espada? ¿Se creerá esto, señor, si no lanzamos un anatema contra el tirano Rosas? ¿Se creerá dentro de 20 años o de 50, si se quiere ir más lejos, a ese hombre tal como es, cuando se sepa que Brown y San Martín le servían fieles y le rendían los homenajes más respetuosos a la par de la Francia y de la Inglaterra? No, señor: dirán, los salvajes unitarios, sus enemigos, mentían. No ha sido un tirano: lejos de eso ha sido un gran hombre, un gran general. Es preciso lanzar sin duda ninguna ese anatema sobre el monstruo... ¡Ojalá hubiéramos imitado al pueblo inglés que arrastró por las calles de Londres el cadáver de Cromwell, y hubiéramos arrastrado a Rosas por las calles de Buenos Aires!... Yo he de estar, señor Presidente, por el proyecto. Si el juicio de Rosas lo librásemos al fallo de la historia, no conseguiremos que Rosas sea condenado como tirano, y sí tal vez que fuese en ella el más grande y el más glorioso de los argentinos.

- ^ Gelman, Jorge (2010). Doscientos años pensando la Revolución de Mayo. Buenos Aires: Sudamericana. p. 130. ISBN 978-950-07-3179-9.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Devoto, Fernando (2009). Historia de la Historiografía Argentina. Buenos Aires: Editorial Sudamericana. p. 181. ISBN 978-950-07-3076-1.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Devoto, Fernando (2009). Historia de la Historiografía Argentina. Buenos Aires: Editorial Sudamericana. p. 202. ISBN 978-950-07-3076-1.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "Puede decirse que hoy ya se ha publicado toda la documentación importante relativa a Rosas y su tiempo. No cabe esperar que aparezcan papeles que puedan volcar los juicios formulados por las distintas corrientes historiográficas. Incluso es dable afirmar que el tema de Rosas ha perdido interés para la mayoría de los historiadores argentinos". Luna, p.47

- ^ "Apaciguada como hoy está la disputa tradicional en torno de la figura de Rosas, el debate histórico acalorado parace haberse desplazado a 1910". Mendelevich, p. 86

- ^ H.Cámara de diputados de la Nación

- ^ Día de la soberanía nacional

- ^ Por decreto, el Gobierno incorporó nuevos feriados al calendario Template:Es

- ^ Emplazaron en Palermo una estatua de Juan Manuel de Rosas

- ^ Galería de los Patriotas Latinoamericanos abrió ante siete presidentes Template:Es