Azawad: Difference between revisions

Danlaycock (talk | contribs) |

|||

| Line 168: | Line 168: | ||

===Religion=== |

===Religion=== |

||

Most are [[Islam|Muslims]], of the [[Sunni]] or [[Sufi]] orientations.{{Citation needed|date=April 2012}} Most popular in the Tuareg movement and northern Mali as a whole is the [[Maliki]] branch of Sufi, in which traditional opinions and analogical reasoning by later Muslim scholars are often used instead of a strict reliance on Ḥadith (coming directly from the |

Most are [[Islam|Muslims]], of the [[Sunni]] or [[Sufi]] orientations.{{Citation needed|date=April 2012}} Most popular in the Tuareg movement and northern Mali as a whole is the [[Maliki]] branch of Sufi, in which traditional opinions and analogical reasoning by later Muslim scholars are often used instead of a strict reliance on Ḥadith (coming directly from the Mohammed’s life and utterances) as a basis for legal judgment.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/360203/Malikiyyah |title=Mālikiyyah |work=Encyclopaedia Britannica |accessdate=16 July 2012}}</ref> |

||

Ansar Dine follows the [[Salafi]] branch of Sunni Islam, which rejects the existence of Islamic holy men (other than |

Ansar Dine follows the [[Salafi]] branch of Sunni Islam, which rejects the existence of Islamic holy men (other than Mohammed) and their teachings. They strongly object to praying around the graves of Malikite 'holymen', burning down one ancient shrine in Timbuctu.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://articles.cnn.com/2012-05-05/africa/world_africa_mali-heritage-sites_1_baba-haidara-sufi-shrines-timbuktu-residents?_s=PM:AFRICA |title=Rebels burn Timbuktu tomb listed as U.N. World Heritage site |date=5 May 2012 |publisher=CNN |accessdate=16 July 2012}}</ref> |

||

At least 90 percent of the 300 [[Christianity|Christians]] who formerly lived in Timbuktu have fled to the South since the rebels captured the town on 2 April 2012.<ref>{{Citation |first=Madeleine |last=Davies |title=Christians in north of Mali flee Tuareg rebels’ control |newspaper=Church Times |date=13 April 2012 |url=http://www.churchtimes.co.uk/content.asp?id=127144 |accessdate=16 June 2012}}</ref> |

At least 90 percent of the 300 [[Christianity|Christians]] who formerly lived in Timbuktu have fled to the South since the rebels captured the town on 2 April 2012.<ref>{{Citation |first=Madeleine |last=Davies |title=Christians in north of Mali flee Tuareg rebels’ control |newspaper=Church Times |date=13 April 2012 |url=http://www.churchtimes.co.uk/content.asp?id=127144 |accessdate=16 June 2012}}</ref> |

||

Revision as of 23:09, 17 September 2012

Azawad ⴰⵣⴰⵓⴷ أزواد Azawad | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2012–2012 | |||||||

Azawad, as claimed by the MNLA, in green, with southern Mali in dark grey. | |||||||

| Status | Unrecognized state | ||||||

| Capital | Timbuktu (proclaimed) Gao (provisional) | ||||||

| Common languages | Tuareg languages, Hassānīya Arabic, Songhay, French, Fula | ||||||

| Religion | Islam | ||||||

| Government | Transitional Council of the State of Azawad (Conseil de Transition de l'Etat de l'Azawad, CTEA) | ||||||

| President | |||||||

• 2012 | Bilal Ag Acherif | ||||||

| Vice President | |||||||

• 2012 | Mahamadou Djeri Maïga | ||||||

| History | |||||||

| 6 April 2012 | |||||||

| 27 June 2012 | |||||||

• Fall of Ansongo | 12 July 2012 | ||||||

| |||||||

Template:Contains Tifinagh text Template:Contains Arabic text

Azawad (Tuareg: ⴰⵣⴰⵓⴷ, Azawd; Arabic: أزواد, Azawād; French: Azawad or Azaouad) is a territory situated in northern Mali as well as a former unrecognised state unilaterally declared by the National Movement for the Liberation of Azawad (MNLA) in 2012 after a Tuareg rebellion drove the Malian Army from the territory. Azawad, as claimed by the MNLA, comprises the Malian regions of Timbuktu, Kidal, Gao, as well as a part of Mopti region,[1] encompassing about 60 percent of Mali's total land area. Azawad borders Burkina Faso to the south, Mauritania to the west and northwest, Algeria to the north and northeast, and Niger to the east and southeast, with undisputed Mali to its southwest. It straddles a portion of the Sahara and the Sahelian zone. Gao is its largest city and served as the temporary capital,[2] while Timbuktu is the second-largest city, and intended to be the capital.[3]

On 6 April 2012, in a statement posted to its website, the MNLA declared "irrevocably" the independence of Azawad from Mali. In Gao on the same day, Bilal Ag Acherif, the secretary-general of the movement, signed the Azawadi Declaration of Independence, which also declared the MNLA as the interim administrators of Azawad until a "national authority" is formed.[4] The proclamation has yet to be recognised by a foreign entity,[5] and even the MNLA's claim to have de facto control of the Azawad region is disputed.[6] The Economic Community of West African States, which refused to recognise Azawad and called the declaration of its independence "null and void", has said it may send troops into the disputed region in support of the Malian claim.[7][8]

On 26 May, the MNLA and its former co-belligerent Ansar Dine announced a pact in which they would merge to form an Islamist state.[9] However, some later reports indicated the MNLA had decided to withdraw from the pact, distancing itself from Ansar Dine.[10][11] Ansar Dine later declared that they rejected the idea of Azawad independence.[12] The MNLA and Ansar Dine continued to clash,[13] culminating in the Battle of Gao on 27 June, in which the Islamist groups Movement for Oneness and Jihad in West Africa and Ansar Dine took control of the city, driving out the MNLA. The following day, Ansar Dine announced that it was in control of all the cities of northern Mali.[14]

Name

According to Robert Brown, Azawad is an Arabic corruption of the Berber word "Azawagh", a dry river basin that covers western Niger, northeastern Mali, and southern Algeria.[15] The name translates to "land of transhumance".[16]

On 6 April 2012, in a statement posted to its website, the MNLA declared the independence of Azawad from Mali. In this Azawad Declaration of Independence the name Independent State of Azawad was used[17] (French: État indépendant de l’Azawad,[17] Arabic: دولة أزواد المستقلة,[18] Dawlat Azawād al-Mustaqillah). On 26 May, the MNLA and its former co-belligerent Ansar Dine announced a pact in which they would merge to form an Islamist state – according to the media the new long name of Azawad was used in this pact. But this new name is not clear – sources list few variants of it: the Islamic Republic of Azawad[19] (French: République islamique de l’Azawad),[20] the Islamic State of Azawad (French: État islamique de l’Azawad[21]), the Republic of Azawad.[22] Azawad authorities didn’t officially confirm any change of name yet. Moreover, some later reports indicated the MNLA had decided to withdraw from the pact with Ansar Dine. In a new statement, dated on 9 June, MNLA uses the name State of Azawad (French: État de l’Azawad).[23] The MNLA has unveiled the list of 28 members of the Transitional Council of the State of Azawad (Conseil de Transition de l'Etat de l'Azawad, CTEA) serving as a provisional government with President Bilal Ag Acherif to manage the new State of Azawad.

History

Gao, Mali and Songhai empires

The Gao Empire owes its name to the town of Gao. In the ninth century AD, it was considered to be the most powerful West African kingdom.

In the early 14th century, the southern part of the region came under the control of the Mali Empire, including the peaceful annexation of Timbuktu by King Musa I in 1324, as he returned from his famous pilgrimage to Mecca.[24]

With the power of the Mali Empire waning in the first half of the 15th century, the area around Timbuktu became relatively autonomous, although Maghsharan Tuareg[who?] had a dominant position.[25] Thirty years later however, the rising Songhay Empire expanded in Gao, absorbing Timbuktu in 1468 or 1469 and much of the surrounding area. The city was led, consecutively, by Sunni Ali Ber (1468–1492), Sunni Baru (1492–1493) and Askia Mohammad I (1493–1528). Although Sunni Ali Ber was in severe conflict with Timbuktu after its conquest, Askia Mohammad I created a golden age for both the Songhay Empire and Timbuktu through an efficient central and regional administration and allowed sufficient leeway for the city's commercial centers to flourish.[25][26] With Gao the capital of the empire, Timbuktu enjoyed a relatively autonomous position. Merchants from Ghadames, Awjilah, and numerous other cities of North Africa gathered there to buy gold and slaves in exchange for the Saharan salt of Taghaza and for North African cloth and horses.[27] Leadership of the Empire stayed in the Askia dynasty until 1591, when internal fights weakened the dynasty's grip.[28]

Moroccan expedition

Following the Battle of Tondibi in a village just north of Gao, the city was captured on 30 May 1591 by an expedition of 4,000 Andalusian Moriscos, 500 mercenaries and 2,500 auxiliaries, including slaves, dubbed the Arma. They were sent by the Saadi ruler of Morocco, Ahmad I al-Mansur, and were led by Morisco General Judar Pasha in search of gold mines. Pasha was born into a family of Spanish Muslims in Morocco, banished by the Spanish Crown following the failed Alpujarras uprising of 1568–71.[29][30] The sacking of Gao marked the effective end of the Songhai as a regional power[31][32] and its economic and intellectual decline,[33] as increasing trans-atlantic trade routes – transporting African slaves, including leaders and scholars of Timbuktu – marginalised Gao and Timbuktu's role as trade and scholarly centers.[34] The consequence of the Moroccan expedition was the formation of the Pashalik of Timbuktu. While initially controlling the Morocco – Timbuktu trade routes, Morocco soon cut its ties with the Arma and the grip of the numerous subsequent pashas on Timbuktu began losing its strength. By 1630, the colony was independent and had been indigenised through intermarriage and local alliances. Songhay never regained control and smaller taifa kingdoms were created.[35] Tuareg temporarily took over control in 1737 and the remainder of the 18th century saw various Tuareg tribes, Bambara and Kounta briefly occupy or besiege the city.[36] During this period, the influence of the Pashas, who by then had mixed with the Songhay through intermarriage, never completely disappeared.[37]

The Massina Empire took control of Timbuktu in 1826, holding it until 1865, when they were driven away by El Hadj Umar Tall's Toucouleur Empire. Sources conflict on who was in control when the French arrived: Elias N. Saad in 1983 suggests the Soninke Wangara,[36] a 1924 article in the Journal of the Royal African Society mentions the Tuareg,[38] while Africanist John Hunwick does not determine one ruler, but notes several states competing for power 'in a shadowy way' until 1893.[39]

Under French rule

| History of Azawad |

|---|

After European powers formalized the scramble for Africa in the Berlin Conference, land between the 14th meridian and Miltou, South-West Chad, became French territory, bounded in the south by a line running from Say, Niger to Baroua. Although the Azawad region was now French in name, the principle of effectivity required France to actually hold power in those areas assigned, e.g. by signing agreements with local chiefs, setting up a government and making use of the area economically, before the claim would be definitive. On 15 December 1893, Timbuktu, by then long past its prime, was annexed by a small group of French soldiers, led by Lieutenant Gaston Boiteux.[40] The region became part of French Sudan (Soudan Français), a colony of France. The colony was reorganised and the name changed several times during the French colonial period. In 1899 the French Sudan was subdivided and the Azawad became part of Upper Senegal and Middle Niger (Haut-Sénégal et Moyen Niger). In 1902 the name became Senegambia and Niger (Sénégambie et Niger) and in 1904 this was changed again to Upper Senegal and Niger (Haut-Sénégal et Niger). This name was used until 1920 when it became French Sudan again.[41]

Under Malian rule

French Sudan became the autonomous state of Mali within the French Community in 1958, and Mali became independent from France in 1960. The area saw four major Tuareg rebellions against Malian rule: the First Tuareg Rebellion (1962–64), the rebellion of 1990–1995, the rebellion of 2007–2009, and a 2012 rebellion.

In the early twenty-first century, the region became notorious for banditry and drug smuggling.[42] The area has been reported to contain a great deal of potential mineral wealth, including petroleum and uranium.[43]

On 17 January 2012, the MNLA announced the start of an insurrection in Azawad against the government of Mali, declaring that it "will continue so long as Bamako does not recognise this territory as a separate entity".[44]

In March 2012, the MNLA and Ansar Dine took control of the regional capitals of Kidal[45] and Gao[46] along with their military bases. On 1 April, Timbuktu was captured.[47] After the seizure of Timbuktu on 1 April, the MNLA gained effective control of most of the territory they claim for an independent Azawad. In a statement released on the occasion, the MNLA invited all Azawadis abroad to return home and join in constructing institutions in the new state.[48]

Unilaterally declared independence

The National Movement for the Liberation of Azawad (MNLA) declared Azawad an independent state on 6 April 2012 and pledged to draft a constitution establishing it as a democracy. Their statement also acknowledged the United Nations charter and said the new state would uphold its principles.[5][49]

In an interview with France 24, an MNLA spokesman declared the independence of Azawad:

Mali is an anarchic state. Therefore we have gathered a national liberation movement to put in an army capable of securing our land and an executive office capable of forming democratic institutions. We declare the independence of Azawad from this day on.

— Moussa Ag Assarid, MLNA spokesman, 6 April 2012[50]

In the same interview, Assarid also promised that Azawad will "respect all the colonial frontiers that separate Azawad from its neighbours" and insisted that Azawad's declaration of independence has "some international legality".[50]

No foreign entity recognized Azawad. The MNLA's declaration was immediately rejected by the African Union, who declared it "null and no value whatsoever". The French Foreign Ministry said it would not recognise the unilateral partition of Mali, but it called for negotiations between the two entities to address "the demands of the northern Tuareg population [which] are old and for too long had not received adequate and necessary responses". The United States also rejected the declaration of independence.[51]

The MNLA is estimated to have up to 3,000 soldiers. ECOWAS declared Azawad "null and void", and said that Mali is "one and [an] indivisible entity". The ECOWAS has said that it would use force, if necessary, to put down the rebellion.[52] The French government indicated it could provide logistical support.[51]

On 26 May, the MNLA and its former co-belligerent Ansar Dine announced a pact in which they would merge to form an Islamist state.[9] However, some later reports indicated the MNLA had decided to withdraw from the pact, distancing itself from Ansar Dine.[53][54] MNLA and Ansar Dine continued to clash,[55] culminating in the Battle of Gao and Timbuktu on 27 June, in which the Islamist groups Movement for Oneness and Jihad in West Africa and Ansar Dine took control of Gao, driving out the MNLA. The following day, Ansar Dine announced that it was in control of Timbuktu and Kidal, the three biggest cities of northern Mali.[56] Ansar Dine continued its offensive against MNLA positions and overran all remaining MNLA held towns by 12 July with the fall of Ansogo.[57]

Geography

The local climate is desert or semi-desert. Reuters wrote of the terrain: "Much of the land is the Sahara desert at its most inhospitable: rock, sand dunes and dust scored by shifting tracks."[58] Some definitions of Azawad also include parts of northern Niger and southern Algeria, adjacent areas to the south and the north[59] though in its declaration of independence, the MNLA did not advance territorial claims on those areas.[17]

Traditionally, Azawad has referred to the sandplains north of Timbuktu. In geological terms, it is a mosaic of river, swamp, lake, and wind-borne deposits, while aeolian processes have proven the most imprinting.[60]

About 6500 BC, Azawad was a 90,000 square kilometres marshy and lake basin. The area of today's Timbuktu was probably permanently flooded. In the deeper parts of Azawad, there were large lakes, partly recharged by rainfall, partly by exposed groundwater. Seasonal lakes and creeks were fed by overflow of the Niger river.[61] The annual Niger flood was diffused throughout the Azawad by a network of palaeochannels spread out over an area of 180 by 130 kilometres. The most important of these paleochannels is the Wadi el-Ahmar, which is 1 200 metres wide at its southern end, at the Niger bend, and winds 70 to 100 kilometres northward. These long interdunal indentations that are framed by Pleistocene longitudinal dunes, charactise the present landscape.[62]

Politics

The MNLA in its declaration of independence announced the first political institutions of the state of Azawad. It included:[63]

- An executive committee, directed by Mahmoud Ag Aghaly.

- A revolutionary council, directed by Abdelkrim Ag Tahar.

- A consultative council, directed by Mahamed Ag Tahadou.

- The general staff of the Liberation Army, directed by Mohamed Ag Najem.

As part of Mali, Azawad did not have a central government, and although the MNLA claimed responsibility for managing the country "until the appointment of a national authority" in their declaration of independence, it has acknowledged the presence of rival armed groups, including Islamist fighters under Ansar Dine, the Movement for Oneness and Jihad in West Africa, and Al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb, in Azawad. The MNLA has yet to establish a formal government, though it has pledged to draft a constitution establishing Azawad as a democracy.[5] The main government building is called the Palace of Azawad by the MNLA. It is a heavily guarded building in central Gao that served as the office of the Gao Region's governor prior to the rebellion.[64]

The military wing of Ansar Dine rejected the MNLA's declaration of independence hours after it was issued.[65] Ansar Dine has vowed to establish Islamic sharia law over all of Mali.[66] At a conference, the Azawadis voiced their disapproval of radical Islamic groups, and asked all foreign fighters to disarm and leave the country.[67]

According to a Chatham House Africa expert, Mali is not to be considered "definitively partitioned". The peoples that constitute a major share of the population of northern Mali, like Songhai and Fulani, would consider themselves to be Malian and have no interest in a separate Tuareg-dominated state.[68] On the day of the declaration of independence, about 200 Malian northerners staged a rally in Bamako, declaring their rejection of the partition and their willingness to fight to drive out the rebels.[69][70] One day later, a new rally against separatism was joined by 2,000 protesters.[71]

According to Ramtane Lamamra, the African Union's peace and security commissioner, the African Union has discussed sending a military force to reunify Mali and that negotiations with terrorists had been ruled out but negotiations with other armed factions are still open.[72]

Administrative divisions

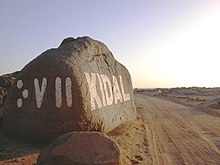

Azawad, as proclaimed by the MNLA, includes the regions of Gao, Timbuktu, Kidal, and the northeast half of Mopti; until 1991, when the new Kidal Region was created, it formed the northern portion of Gao Region. As such, it includes the three biggest cities of Timbuktu, Gao and Kidal.[59]

Demographics

Northern Mali has a population density of 1.5 people per square kilometre.[73] The Malian regions that are claimed by Azawad are listed hereafter (apart from the portion of Mopti Region claimed and occupied by the MNLA). The population figures are from the 2009 census of Mali, taken before Azawadi independence was proclaimed.[74] Since the start of the Tuareg rebellion in January 2012, probably 250,000 former inhabitants have fled from the territory.[75]

| Region name | Area (km2)[citation needed] | Population[citation needed] |

|---|---|---|

| Gao | 170,572 | 544,120 |

| Kidal | 151,430 | 67,638 |

| Timbuktu | 497,926 | 681,691 |

| Subtotal | 819,928 | 1,293,449 |

| Northeast half of Mopti | 55,600 | 1,220,000 |

| Total | 875,528 | 2,517,920 |

Ethnic groups

The area was traditionally inhabited by the settled Songhay, nomadic Tuareg people, Moors, and Fulas (Template:Lang-ff; French: Peul)[76] The ethnic composition of the regions in 1950 (at that time, Kidal Region was a part of Gao Region) is shown in the diagrams to the left.

Languages

(left side in Tifinagh: "k´l")

The languages of Azawad include Tamashek, Hassānīya Arabic, Fulfulde and Songhay.[77][78] French is the language of school and administration.[citation needed]

Religion

Most are Muslims, of the Sunni or Sufi orientations.[citation needed] Most popular in the Tuareg movement and northern Mali as a whole is the Maliki branch of Sufi, in which traditional opinions and analogical reasoning by later Muslim scholars are often used instead of a strict reliance on Ḥadith (coming directly from the Mohammed’s life and utterances) as a basis for legal judgment.[79]

Ansar Dine follows the Salafi branch of Sunni Islam, which rejects the existence of Islamic holy men (other than Mohammed) and their teachings. They strongly object to praying around the graves of Malikite 'holymen', burning down one ancient shrine in Timbuctu.[80]

At least 90 percent of the 300 Christians who formerly lived in Timbuktu have fled to the South since the rebels captured the town on 2 April 2012.[81]

Humanitarian situation

The people living in the central and northern Sahelian and Sahelo-Saharan areas of Mali are the country's poorest, according to an International Fund for Agricultural Development report. Most of them are pastoralists and farmers practicing subsistence agriculture on dry land with poor and increasingly degraded soils.[82] The northern part of Mali suffers from a critical shortage of food and lack of health care. Starvation has prompted about 200,000 inhabitants to leave the region.[83]

Refugees, in the 92,000-person refugee camp at Mbera, Mauritania, describe the Islamists as "intent on imposing an Islam of lash and gun on Malian Muslims." The Islamists in Timbuktu have destroyed about a half-dozen venerable above-ground tombs of revered holy men, proclaiming the tombs contrary to Shariah. One refugee in the spoke of encountering Afghans, Pakistanis and Nigerians.[84]

See also

- Arab Islamic Front of Azawad

- List of states with limited recognition

- Niger Movement for Justice

- Popular Movement for the Liberation of Azawad

- Tuareg rebellion (2007–2009)

References

- ^ "Mali Tuareg rebels control Timbuktu as troops flee". BBC News. 1 April 2012. Retrieved 3 April 2012.

- ^ "Tuaregs claim 'independence' from Mali". Al Jazeera. 6 April 2012. Retrieved 6 April 2012.

- ^ "[[Mali]]: A scramble for power". The Muslim News. 8 April 2012. Retrieved 8 April 2012.

{{cite news}}: URL–wikilink conflict (help) - ^ "Mali rebels declare independence in north". Times of India. 6 April 2012. Retrieved 6 April 2012.

- ^ a b c "Tuareg rebels declare the independence of Azawad, north of Mali". Al Arabiya. 6 April 2012. Retrieved 6 April 2012.

- ^ J. David Goodman (6 April 2012). "Rift Appears Between Islamists and Main Rebel Group in Mali". The New York Times. Retrieved 7 April 2012.

- ^ "ECOWAS calls declaration of Azawad independence ''null and void''". Panapress.com. 6 April 2012. Retrieved 9 June 2012.

- ^ "Ecowas To Send 3,000 Troops To Mali, Guinea-Bissau To Reinstate Civilian Rule - International Business Times". Ibtimes.com. Retrieved 9 June 2012.

- ^ a b "Mali Tuareg and Islamist rebels agree on Sharia state". BBC News. 26 May 2012. Retrieved 27 May 2012. Cite error: The named reference "BBC265" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Biiga, Bark (3 June 2012). "Nord Mali: le MNLA refuse de se mettre "en sardine"!" (in French). FasoZine. Retrieved 3 June 2012.

- ^ "Mali Islamists Reopen Talks With Tuareg Rebels". Voice of America. 2 June 2012. Retrieved 2 June 2012.

- ^ "Mali Islamists want sharia not independence". AFP. Google News. 20 June 2012. Retrieved 28 July 2012.

- ^ "Mali rebel groups 'clash in Kidal'". BBC News. 8 June 2012.

- ^ Tiemoko Diallo (28 June 2012). "Islamists declare full control of Mali's north". Reuters. Retrieved 28 July 2012.

{{cite news}}: Missing|author1=(help); Unknown parameter|author 2=ignored (help) - ^ Robert Brown (1896). Annotations to The history and description of Africa, by Leo Africanus. The Hakluyt Society. Retrieved 3 April 2012.

- ^ Germain B. Nama (1 March 2012). "Rebelles touaregs : "Pourquoi nous reprenons les armes…"". Courrier International (in French). Retrieved 5 April 2012.

- ^ a b c Bilal Ag Acherif (6 April 2012). "Déclaration d'indépendence de l'Azawad" (in French). National Movement for the Liberation of Azawad. Retrieved 6 April 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ Bilal Ag Acherif (6 April 2012). "بيان استقلال أزواد" (in Arabic). National Movement for the Liberation of Azawad. Retrieved 28 April 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ "Mali Tuareg and Islamist rebels agree on Islamist state". BBC News. 27 May 2012. Retrieved 31 May 2012.

- ^ Allimam Mahamane (31 May 2012). "Proclamation de la République Islamique de l'Azawad : La vraie face de l'irrédentisme et de l'intégrisme s'affiche" (in French). MaliActu. Retrieved 31 May 2012.

- ^ "Nord-Mali : la rébellion crée un État islamique" (in French). Le Figaro. 27 May 2012. Retrieved 31 May 2012.

- ^ Katarina Höije (27 May 2012). "Mali rebel groups join forces, vowing an Islamic state". CNN. Retrieved 31 May 2012.

- ^ Bilal Ag Acherif (9 June 2012). "Mis en place un Conseil Transitoire de l'Etat de l'AZAWAD (CTEA)" (in French). National Movement for the Liberation of Azawad. Retrieved 11 June 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ Hunwick 2003, pp. 9–10.

- ^ a b Saad 1983, p. 11.

- ^ Fage 1956, pp. 27.

- ^ "Timbuktu". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. Retrieved 5 November 2010.

- ^ Fage 1956, pp. 27–29.

- ^ Prieto, José (2001). Exploradores españoles olvidados de África. Madrid: Sociedad Geográfica Española.

- ^ Bovill, EW (1927). "The Moorish Invasion of The Sudan". African Affairs (XXVII). Royal African Society: 47–56.

- ^ Hunwick 2003, p. 192.

- ^ Kaba 1981.

- ^ Hunwick 2000, p. 508.

- ^

Pelizzo, Riccardo (2001). "Timbuktu: A Lesson in Underdevelopment" (PDF). Journal of World-Systems Research. 7 (2): 265–283. Retrieved 25 March 2010.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ Michael Dumper, Bruce E. Stanley (2007). Cities of The Middle East and North Africa: A Historical Encyclopedia. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 1-57607-919-8.

- ^ a b Saad 1983, p. 206-214.

- ^ Saad 1983, p. 206-209.

- ^ Maugham, R.C.F. (1924). "Native Land Tenure in the Timbuktu Districts". Journal of the Royal African Society. 23 (90). Oxford: Oxford University Press: 125–130. JSTOR 715389.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ Hunwick 2003, p. xvi.

- ^ Hacquard 1900, p. 71; Dubois & White 1896, p. 358

- ^ Imperato 1989, pp. 48–49.

- ^ "Une zone immense et incontrôlable aux confins du Sahara" (in Template:Fr icon). La-croix.com. Retrieved 9 June 2012.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ "Le secteur minier du Mali, un potentiel riche mais inexploité". Les Journées Minières et Pétrolières du Mali. 2011. Retrieved 3 April 2012.

- ^ "The Renewal of Armed Struggle in Azawad". Mouvement National de libération de l'Azawad. 17 January 2012. Retrieved 2 April 2012.

- ^ "Mali coup: Rebels seize desert town of Kidal". BBC News. 30 March 2012. Retrieved 30 March 2012.

- ^ "Mali Tuareg rebels seize key garrison town of Gao". BBC News. 31 March 2012. Retrieved 1 April 2012.

- ^ Rukmini Callimachi (1 April 2012). "Mali coup leader reinstates old constitution". Associated Press. Retrieved 31 March 2012.

- ^ "Declaration du Bureau Politique" (in French). Mouvement National de libération de l'Azawad. 1 April 2012. Retrieved 2 April 2012.

- ^ Bate Felix (6 April 2012). "Mali rebels declare independence in north". Reuters. Retrieved 6 April 2012.

- ^ a b "Tuareg rebels declare independence in north Mali". France 24. 6 April 2012. Retrieved 6 April 2012.

- ^ a b Felix, Bate (6 April 2012). "AU, US reject Mali rebels' independence declaration". Reuters. Retrieved 7 April 2012.

- ^ "Azawad independence: ECOWAS calls declaration of Azawad independence 'null and void'". Afrique en Ligue. 7 April 2012. Retrieved 8 April 2012.

- ^ Biiga, Bark (3 June 2012). "Nord Mali: le MNLA refuse de se mettre "en sardine"!" (in French). FasoZine. Retrieved 3 June 2012.

- ^ "Mali Islamists Reopen Talks With Tuareg Rebels". Voice of America. 2 June 2012. Retrieved 2 June 2012.

- ^ "Mali rebel groups 'clash in Kidal'". BBC News. 8 June 2012.

- ^ Tiemoko Diallo and Adama Diarra (28 June 2012). "Islamists declare full control of Mali's north". Reuters. Retrieved 29 June 2012.

- ^ http://www.france24.com/en/20120712-al-qaeda-linked-islamists-drive-malis-tuaregs-last-stronghold-ansogo-timbuktu-mnla-ansar-dine-mujao

- ^ "FACTBOX-'Azawad': self-proclaimed Tuareg state". Reuters AlertNet. 6 April 2012. Retrieved 6 April 2012.

- ^ a b "Who are the Tuareg?". Al Jazeera. 14 July 2008. Retrieved 3 April 2012.

- ^ McIntosh, 2008, p. 33

- ^ McIntosh, 2008, p. 34

- ^ McIntosh, 2008, p. 35

- ^ Salima Tlemçani (7 April 2012) "Le mali dans la tourmente : AQMi brouille les cartes à l’Azawad", El Watan.

- ^ "Malians protest against Azawad independence". The Telegraph. 6 April 2012. Retrieved 6 April 2012.

- ^ "Confusion in Mali after Tuareg independence claim". 6 April 2012. Retrieved 6 April 2012.

- ^ "Qaeda using Mali crisis to expand, France warns". Vision. 4 April 2012. Retrieved 6 April 2012.

- ^ Jemal Oumar (30 April 2012). "Azawad rejects armed groups". Magharebia. Magharebia.com.

- ^ "Rebels declare independent state", Herald Sun, 7 April 2012.

- ^ Felix, Bate (6 April 2012), "AU, US reject Mali rebels' independence declaration", Reuters

- ^ "Malians protest against Azawad independence". The New York Times. 7 April 2012. Retrieved 7 April 2012.

- ^ "Protests in Bamoko as Malians reject independence of North", Euronews, 8 April 2012

- ^ Nossiter, Adam (18 July 2012). "Jihadists' Fierce Justice Drives Thousands to Flee Mali". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 12 August 2012. Retrieved 12 August 2012.

- ^ Mali – Population, Encyclopedia of the Nations, retrieved 2 April 2012

- ^ (In French.) "Resultats provisoires R.G.P.H. 2009" (Document). République de Mali: Institut National de la StatistiqueTemplate:Inconsistent citations

{{cite document}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|url=ignored (help)CS1 maint: postscript (link). - ^ Meo, Nick (7 April 2012), "Triumphant Tuareg rebels fall out over al-Qaeda's jihad in Mali", The Telegraph

- ^ File:Statistiques.JPG

- ^ "Languages of Mali". Ethnologue.com. Retrieved 6 April 2012.

- ^ Heath, Jeffrey (1999). A Grammar of Koyra Chiini: the Songhay of Timbuktu. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co. KG. pp. 4–5.

- ^ "Mālikiyyah". Encyclopaedia Britannica. Retrieved 16 July 2012.

- ^ "Rebels burn Timbuktu tomb listed as U.N. World Heritage site". CNN. 5 May 2012. Retrieved 16 July 2012.

- ^ Davies, Madeleine (13 April 2012), "Christians in north of Mali flee Tuareg rebels' control", Church Times, retrieved 16 June 2012

- ^ Ghosh, Palash R. (12 April 2012), "Azawad: The Tuaregs' Nonexistent State In A Desolate, Poverty-Stricken Wasteland", International Business Times

- ^ Nkrumah, Gamal (12–18 April 2012). "Saharan quicksand". Al-Ahram Weekly Online. Retrieved 13 April 2012.

- ^ Nossiter, Adam (18 July 2012). "Jihadists' Fierce Justice Drives Thousands to Flee Mali". The New York Times.

{{cite news}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help)

Bibliography

- Dubois, Felix; White, Diana (trans.) (1896). Timbuctoo the mysterious. New York: LongmansTemplate:Inconsistent citations

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)CS1 maint: postscript (link). - Fage, J. D. (1956). An Introduction to the History of West Africa. London: Cambridge University Press. p. 22Template:Inconsistent citations

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)CS1 maint: postscript (link) - Hacquard, Augustin (1900). "Monographie de Tombouctou" (Document). Paris: Société des études coloniales & maritimesTemplate:Inconsistent citations

{{cite document}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|url=ignored (help)CS1 maint: postscript (link). Also available from Gallica. - Hunwick, J. O. (2000). "Timbuktu". Encyclopaedia of Islam. Volume X (2nd ed.). Leiden: Brill. pp. 508–510. ISBN 90-04-11211-1Template:Inconsistent citations

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)CS1 maint: postscript (link). - Hunwick, John O. (2003). Timbuktu and the Songhay Empire: Al-Sadi's Tarikh al-Sudan down to 1613 and other contemporary documents. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 0585-6914Template:Inconsistent citations

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: length (help); Invalid|ref=harv(help)CS1 maint: postscript (link). First published in 1999 as ISBN 90-04-11207-3. - Imperato, Pascal James (1989). Mali: A Search for Direction. Westview Press. ISBN 1-85521-049-5Template:Inconsistent citations

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|unused_data=ignored (help)CS1 maint: postscript (link). - Kaba, Lansine (1981). "Archers, Musketeers, and Mosquitoes: The Moroccan Invasion of the Sudan and the Songhay Resistance (1591–1612)". Journal of African History. 22 (4): 457–475. doi:10.1017/S0021853700019861. JSTOR 181298. PMID 11632225Template:Inconsistent citations

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)CS1 maint: postscript (link). - Kirkby, Coel; Murray, Christina (2010). "Elusive Autonomy in Sub-Saharan Africa". In Weller, Marc; Nobbs, Katherine (eds.). Asymmetric Autonomy and the Settlement of Ethnic Conflicts. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. pp. 97–120. ISBN 978-0-8122-4230-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - McIntosh, Roderick J. (2008), "Before Timbuktu: cities of the Elder World" (PDF), The Meanings of Timbuktu, HSRC Press, pp. 31–43, retrieved 9 April 2012

- Saad, Elias N. (1983). Social History of Timbuktu: The Role of Muslim Scholars and Notables 1400–1900. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-24603-2Template:Inconsistent citations

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)CS1 maint: postscript (link).

External links

![]() Media related to Azawad at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Azawad at Wikimedia Commons