Trevor Huddleston: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 43: | Line 43: | ||

After his retirement from episcopal office in 1983, Huddleston started anti-Apartheid work outside of South Africa, having become President of the Anti-Apartheid movement in 1981. |

After his retirement from episcopal office in 1983, Huddleston started anti-Apartheid work outside of South Africa, having become President of the Anti-Apartheid movement in 1981. |

||

In 1994 he received honours from Tanzania (Torch of Kilimanjaro) and was awarded the Indira Gandhi Award for Peace, Disarmament |

In 1994 he received honours from Tanzania (Torch of Kilimanjaro) and was awarded the Indira Gandhi Award for Peace, Disarmament and Development. In the 1998 [[New Year Honours]] he was appointed a [[Knight Commander of the Order of St Michael and St George]] (KCMG).<ref>{{London Gazette|issue=54993|supp=yes|startpage=3|date=30 December 1997|accessdate=2008-01-16}}</ref> |

||

==Death and legacy== |

==Death and legacy== |

||

Revision as of 10:07, 6 January 2013

The Most Reverend Trevor Huddleston | |

|---|---|

| Archbishop of the Indian Ocean | |

| |

| Province | Province of the Indian Ocean |

| Diocese | Mauritius |

| Installed | 1978 |

| Term ended | 1983 |

| Predecessor | (Ernest) Edwin Curtis |

| Successor | French Chang-Him |

| Other post(s) | Bishop of Masasi Bishop of Stepney Bishop of Mauritius Archbishop of the Indian Ocean |

| Orders | |

| Ordination | 1936 (deacon) 1937 (priest) |

| Consecration | 1960 |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 15 June 1913 Bedford, England |

| Died | 20 April 1998 (aged 84) Mirfield, West Yorkshire |

| Part of a series on |

| Apartheid |

|---|

|

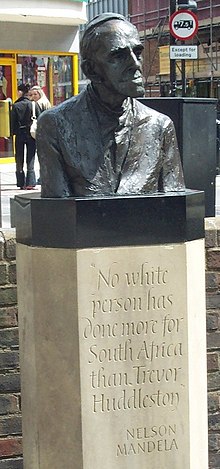

Ernest Urban Trevor Huddleston CR, KCMG (15 June 1913 – 20 April 1998) was an English Anglican bishop. He was most well known for his anti-apartheid activism and his 'Prayer for Africa'.[1][2] He was the second Archbishop of the Church of the Province of the Indian Ocean.

Early life

Huddleston was born in Bedford, England, and educated at Lancing College (1927–1931),[3] Christ Church, Oxford, and at Wells Theological College. He joined an Anglican religious order, the Community of the Resurrection (CR), in 1939, taking vows in 1941,[4] having already served for over two years as a curate at St Mark's Swindon.[4]

South Africa

In 1943, Huddleston went to the CR mission station at Rosettenville, Sophiatown (Johannesburg, South Africa). He was sent there to build on the work of Raymond Raynes CR, whose monumental efforts there had proved to be so demanding that the community summoned him back to Mirfield in order to recuperate. Raynes was deeply concerned about who should be appointed to succeed him. He met Huddleston (at that stage still a novice in the community) who had been appointed to nurse him while he was in the infirmary. As a result of that meeting, much to Huddleston's surprise, Raynes was convinced that he had found his successor.

Over the course of the next 13 years in Sophiatown, Huddleston developed into a much-loved priest and respected anti-Apartheid activist, earning him the nickname Makhalipile ("dauntless one"). He fought against the Apartheid laws and in 1955 the ANC gave him the rare honour of bestowing on him the title Isitwalandwe at the famous Freedom Congress in Kliptown.

Return to England, Tanzania and Mauritius

Huddleston's order asked him to return to England in 1956, where he worked as the master of novices at the CR's Mirfield mother house in West Yorkshire for two years,[4] and then Prior of the Order's branch priory in London[4] where he remained until his election as a bishop. He was consecrated Bishop of Masasi (Tanzania) in 1960, where he worked for eight years, before becoming Bishop of Stepney (a suffragan bishop in the Diocese of London).[5] After 10 years in England, he was appointed (in 1978) Bishop of Mauritius, a diocese of the Province of the Indian Ocean, and later the same year was elected Archbishop of the Province of the Indian Ocean.[4]

After retirement

After his retirement from episcopal office in 1983, Huddleston started anti-Apartheid work outside of South Africa, having become President of the Anti-Apartheid movement in 1981.

In 1994 he received honours from Tanzania (Torch of Kilimanjaro) and was awarded the Indira Gandhi Award for Peace, Disarmament and Development. In the 1998 New Year Honours he was appointed a Knight Commander of the Order of St Michael and St George (KCMG).[6]

Death and legacy

Huddleston died at Mirfield, West Yorkshire, England. A window in memory of him is at the Lancing College chapel and was visited by Desmond Tutu. They became friends after Huddleston visited Desmond as a boy ill in hospital with TB, and subsequently worked together opposing Apartheid. The Huddleston Centre in Hackney has been delivering youth provision to disabled young people living in Hackney for over 30 years, and continues to do so. The centre bears Trevor's surname after he intervened to ensure that part of a church building was converted to provide an accessible nursery, play (and latterly youth club) space for disabled young people in Hackney, regardless of their faith.[7] The Trevor Huddleston Memorial Centre in Sophiatown was established in 1999, following Trevor's death (in 1998) and the internment of his ashes in the garden of Christ the King church Sophiatown, where he had served for 13 years (see above). This Centre delivers youth development programmes as well as heritage and cultural projects promoting Huddleston's passion for young people, and his commitment to non-racialism, multi-faith work, and social justice.[8]

Prayer for Africa

A noted and famous prayer of Huddleston's is the "Prayer for Africa" which has been recited throughout South Africa, Tanzania and in other African countries:[2]

God bless Africa,

Guard her people,

Guide her leaders,

And give her peace.

Alternative version (with emphasis on children):

God Bless Africa;

Guard her children;

Guide her leaders

And give her peace, for Jesus Christ's sake.

Amen.[9]

Another alternative version:

God bless Africa, God bless Africa

Guard her children, guide her leaders.

God bless Africa, God bless Africa,

God bless Africa and bring her peace.

Naught for Your Comfort

Huddleston wrote Naught for Your Comfort.[10] The book was significantly important as it discussed the abuse of black people by American authorities.[citation needed]

See also

References

- ^ "The birth and death of apartheid". Retrieved 17 June 2002.

- ^ a b http://www.brainyquote.com/quotes/quotes/t/trevorhudd114515.html

- ^ See College website for details.

- ^ a b c d e Archbishops' Council of the Church of England (2011). "Crockford Clerical Directory". Church House Publishing.

{{cite web}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameters:|month=and|coauthors=(help); Missing or empty|url=(help); Unknown parameter|http://www.crockford.org.uk/clergy.asp?id=ignored (help) - ^ "No. 44628". The London Gazette. 5 July 1968.

- ^ "No. 54993". The London Gazette (invalid

|supp=(help)). 30 December 1997. - ^ http://www.huddlestoncentre.org

- ^ http://www.trevorhuddleston.org

- ^ "http://www.worldprayers.org/archive/prayers/invocations/god_bless_africa.html

- ^ Collins, 1956

External links

- Audio samples

- Obituary by Aelred Stubbs

- The Life and Work of Archbishop Trevor Huddleston: links and biography on ANC website

- Items from the Press on the Death of Archbishop Trevor Huddleston: ANC website

- Trevor Huddleston CR Memorial Centre, Sophiatown, Johannesburg, South Africa

- Naught for Your Comfort online text at archive.org

- 1913 births

- 1998 deaths

- 20th-century Anglican archbishops

- Alumni of Christ Church, Oxford

- Archbishops of the Indian Ocean

- Bishops of Masasi

- Bishops of Mauritius

- Bishops of Stepney

- British expatriates in South Africa

- Christianity in Africa

- English Anglican priests

- English religious writers

- Housing struggles in South Africa

- International opponents of apartheid in South Africa

- Knights Commander of the Order of St Michael and St George

- Members of Anglican religious orders

- People educated at Lancing College

- People from Bedford

- Recipients of the Indira Gandhi Peace Prize

- South African Anglicans