The Matrix Reloaded: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

Reverted 1 edit by 2a02:1205:5004:8ca0:3052:c6ca:5e86:67bc (talk): Source needed. (TW) |

||

| Line 19: | Line 19: | ||

}} |

}} |

||

'''''The Matrix Reloaded''''' is a 2003 American–Australian [[Science fiction film|science fiction]] [[action film]] and the second installment in [[The Matrix (franchise)|''The Matrix'' trilogy]], written and directed by [[The Wachowskis|The Wachowski Brothers]]. It premiered on May 7, 2003, in [[Westwood, Los Angeles, California]], and went on general release by [[Warner Bros.]] in [[North America]]n theaters on May 15, 2003, and around the world during the latter half of that month. It was also screened out of competition at the [[2003 Cannes Film Festival]].<ref name="festival-cannes.com">{{cite web |url=http://www.festival-cannes.com/en/archives/ficheFilm/id/4075505/year/2003.html |title=Festival de Cannes: The Matrix Reloaded |accessdate=2009-11-10|work=festival-cannes.com}}</ref> The [[video game]] ''[[Enter the Matrix]]'', which was released on May 15, and a collection of nine animated shorts, ''[[The Animatrix]]'', which was released on June 3, supported and expanded the storyline of the movie. ''[[The Matrix Revolutions]]'', which completes the story, was released six months after ''Reloaded'', in November 2003. |

'''''The Matrix Reloaded''''' is a 2003 American–Australian [[Science fiction film|science fiction]] [[action film]] and the second installment in [[The Matrix (franchise)|''The Matrix'' trilogy]], written and directed by [[The Wachowskis|The Wachowski Brothers]]. It premiered on May 7, 2003, in [[Westwood, Los Angeles, California]], and went on general release by [[Warner Bros.]] in [[North America]]n theaters on May 15, 2003, and around the world during the latter half of that month. It was also screened out of competition at the [[2003 Cannes Film Festival]].<ref name="festival-cannes.com">{{cite web |url=http://www.festival-cannes.com/en/archives/ficheFilm/id/4075505/year/2003.html |title=Festival de Cannes: The Matrix Reloaded |accessdate=2009-11-10|work=festival-cannes.com}}</ref> The [[video game]] ''[[Enter the Matrix]]'', which was released on May 15, and a collection of nine animated shorts, ''[[The Animatrix]]'', which was released on June 3, supported and expanded the storyline of the movie. ''[[The Matrix Revolutions]]'', which completes the story, was released six months after ''Reloaded'', in November 2003. |

||

It's the 50th highest grossing film of all time. |

|||

==Plot== |

==Plot== |

||

Revision as of 00:07, 2 June 2013

| The Matrix Reloaded | |

|---|---|

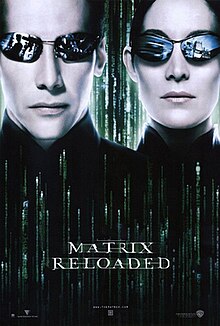

Theatrical poster featuring Neo and Trinity | |

| Directed by | The Wachowski Brothers |

| Written by | The Wachowski Brothers |

| Produced by | Joel Silver |

| Starring | Keanu Reeves Laurence Fishburne Carrie-Anne Moss Hugo Weaving Harold Perrineau Randall Duk Kim Jada Pinkett Smith |

| Cinematography | Bill Pope |

| Edited by | Zach Staenberg |

| Music by | Don Davis |

Production companies | |

| Distributed by | Warner Bros. Pictures |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 138 minutes |

| Countries | United States Australia |

| Budget | $127[1]–$150[2] million |

| Box office | $742,128,461[2] |

The Matrix Reloaded is a 2003 American–Australian science fiction action film and the second installment in The Matrix trilogy, written and directed by The Wachowski Brothers. It premiered on May 7, 2003, in Westwood, Los Angeles, California, and went on general release by Warner Bros. in North American theaters on May 15, 2003, and around the world during the latter half of that month. It was also screened out of competition at the 2003 Cannes Film Festival.[3] The video game Enter the Matrix, which was released on May 15, and a collection of nine animated shorts, The Animatrix, which was released on June 3, supported and expanded the storyline of the movie. The Matrix Revolutions, which completes the story, was released six months after Reloaded, in November 2003.

Plot

Six months after the events of the first movie, Morpheus receives a message from Captain Niobe of the Logos calling an emergency meeting of all of Zion's ships. Zion has confirmed the last transmission of the Osiris: an army of Sentinels is tunneling towards Zion and will reach it within 72 hours. Commander Lock orders all ships to return to Zion to prepare for the onslaught. Morpheus asks a ship to remain in order to contact the Oracle, in defiance of the order. The Caduceus receives a message from the Oracle, and the Nebuchadnezzar ventures out so Neo can contact her. One of the Caduceus crew, Bane, encounters Agent Smith, who takes over Bane's avatar. Smith then uses this avatar to leave the Matrix, gaining control of Bane's real body.

In Zion, Morpheus announces the news of the advancing machines to the people. Neo receives a message from the Oracle and returns to the Matrix to her bodyguard Seraph, who then leads them to her. After realizing that the Oracle is part of the Matrix, Neo asks how he can trust her; she replies that it is his decision. The Oracle instructs Neo to reach the Source of the Matrix by finding the Keymaker, a prisoner of the Merovingian. As the Oracle departs, Smith appears, telling Neo that after being defeated, he refused to be deleted, and is now a rogue program. He demonstrates his ability to clone himself using other people in the Matrix, including other Agents, as hosts. He then tries to absorb Neo as a host, but fails, prompting a battle between Neo and Smith's clones. Neo manages to defend himself, but is forced to retreat from the increasingly overwhelming numbers.

Neo, Morpheus and Trinity visit the Merovingian and ask for the Keymaker, but the Merovingian refuses. His wife Persephone, tired of her husband's attitude, betrays him and leads the trio to the Keymaker. The Merovingian soon arrives with his men. Morpheus, Trinity and the Keymaker escape, while Neo holds off the Merovingian's servants. Morpheus and Trinity try to escape with the Keymaker on the highway, facing several Agents and The Twins. Morpheus defeats The Twins; Trinity escapes, and Neo flies in to save Morpheus and the Keymaker.

In the real world, Zion's remaining ships prepare to battle the machines. Within the Matrix, the crews of the Nebuchadnezzar, Vigilant and Logos help the Keymaker and Neo reach the door to the Source. The crew of the Logos must destroy a power plant to prevent a security system from being triggered, and the crew of the Vigilant must destroy a back-up power station. The Logos is successful, while the Vigilant is bombed by a Sentinel in the real world, killing everyone on board. Although Neo requested that Trinity remain on the Nebuchadnezzar, she enters the Matrix to replace the Vigilant crew and complete their mission. However, her escape is compromised by an Agent, and they fight. As Neo, Morpheus and the Keymaker try to reach the Source, the Smiths appear and try to kill them. The Keymaker unlocks the door to the Source, allowing Neo and Morpheus to escape, but the Keymaker is killed.

Neo meets a program called the Architect, the Matrix's creator. The Architect explains that Neo is part of the design of the Matrix, and unless Neo returns to the Source to reboot the Matrix and pick survivors to repopulate the soon-to-be-destroyed Zion, the Matrix will crash, killing everyone connected to it. Combined with Zion's utter destruction, this would mean mankind's extinction, but the machines would survive. Neo learns of Trinity's situation and chooses to save her instead. As she falls off a building, he flies in and catches her, then removes a bullet from her body and restarts her heart.

Back in the real world, Sentinels destroy the Nebuchadnezzar. Neo displays a new ability to disable the machines with his thoughts, but falls into a coma from the effort. The crew are picked up by another ship, the Hammer. Its captain, Roland, reveals the remaining ships were wiped out by the machines after someone activated an EMP too early, and Bane is revealed as the only survivor.

Cast

- Keanu Reeves as Neo

- Laurence Fishburne as Morpheus

- Carrie-Anne Moss as Trinity

- Hugo Weaving as Smith

- Neil and Adrian Rayment as the Twins

- Jada Pinkett Smith as Niobe

- Monica Bellucci as Persephone

- Harold Perrineau as Link

- Randall Duk Kim as The Keymaker

- Gloria Foster as The Oracle

- Helmut Bakaitis as The Architect

- Lambert Wilson as The Merovingian

- Daniel Bernhardt as Agent Johnson

- Leigh Whannell as Axel

- Collin Chou as Seraph

- Nona Gaye as Zee

- Gina Torres as Cas

- Anthony Zerbe as Councillor Hamann

- Roy Jones, Jr. as Captain Ballard

- David A. Kilde as Agent Jackson

- Matt McColm as Agent Thompson

- Harry Lennix as Commander Lock

- Cornel West as Councillor West

- Steve Bastoni as Captain Soren

- Anthony Wong as Ghost

- Clayton Watson as Kid

- Ian Bliss as Bane

Zee was originally played by Aaliyah, who died in a plane crash on August 25, 2001 before filming was complete, requiring her scenes to be reshot with actress Nona Gaye.[4][5]

Production

Filming

The Matrix Reloaded was largely filmed at Fox Studios in Australia, concurrently with filming of the sequel, Revolutions. The freeway chase and "Burly Brawl" scenes were filmed at the decommissioned Naval Air Station Alameda in Alameda, California. The producers constructed a 1.5-mile freeway on the old runways specifically for the film. Some portions of the chase were also filmed in Oakland, California, and the tunnel shown briefly is the Webster Tube, which connects Oakland and Alameda. Some post-production editing was also done in old aircraft hangars on the base as well.

The city of Akron, Ohio was willing to give full access to Route 59, the stretch of freeway known as the "Innerbelt", for filming of the freeway chase when it was under consideration. However, producers decided against this as "the time to reset all the cars in their start position would take too long".[6] MythBusters would later reuse the Alameda location in order to explore the effects of a head-on collision between two semi trucks, and to perform various other experiments.

Around 97% of the materials from the sets of the film were recycled after production was completed; for example, tons of wood were sent to Mexico to build low-income housing.[7]

Some scenes from the film Baraka by Ron Fricke were selected to represent the real world shown by the wallmonitors in the Architect's room.[8] The scene where The Oracle (Gloria Foster) appears were filmed before her death in September 29, 2001.

Visual effects

Following the success of the previous film, the Wachowskis came up with extremely difficult action sequences, such as the Burly Brawl, a scene in which Neo had to fight 100 Smiths. To develop technologies for the film, Warner Bros. launched ESC Entertainment.[9]

The ESC team tried to figure out how to bring the Wachowskis' vision to the screen, but because the bullet time required arrays of carefully aligned cameras and months of planning, even for a brief scene featuring two or three actors, a scene like the Burly Brawl as the brothers envision would require more so, and even take years of compositing. Eventually John Gaeta realized that the technology he and his crew had developed for The Matrix's bullet time was no longer sufficient and concluded they needed a virtual camera. Having before used real photographs of building as texture for 3D models in The Matrix, the team started digitizing all data, such as scenes, characters' motions, or even the reflectivity of Neo's cassock.

They developed "Universal Capture", a process which samples and stores facial details and expressions at high resolution, then capture expressions from Reeves and Weaving. The algorithm was written by Borshukov, who had also created the photo-realistic buildings for the visual effects in The Matrix. With this collected wealth of data, they finally were able to create virtual cinematography in which characters, locations, and events can all be created digitally and viewed through virtual cameras, eliminating the restrictions of real cameras, years of compositing data, and replacing the use of still camera arrays or, in some scenes, cameras altogether. The ESC team render the final effects using the program mental ray.[9]

Music

Don Davis, who composed the music for The Matrix, returned to score Reloaded. For many of the pivotal action sequences, such as the "Burly Brawl", he collaborated with Juno Reactor. Some of the collaborative cues by Davis and Juno Reactor are extensions of material by Juno Reactor; for example, a version of "Komit" featuring Davis' strings is used during a flying sequence, and "Burly Brawl" is essentially a combination of Davis' unused "Multiple Replication" and a piece similar to Juno Reactor's "Masters of the Universe". One of the collaborations, "Mona Lisa Overdrive", is titled in reference to the cyberpunk novel of the same name by William Gibson, a major influence on the directors. Leitmotifs established in The Matrix return - such as the Matrix main theme, Neo and Trinity's love theme, the Sentinel's theme, Neo's flying theme, and a more frequent use of the four-note Agent Smith theme - and others used in Revolutions are established.

As with its predecessor, many tracks by external musicians are featured in the movie, its closing credits, and the soundtrack album, some of which were written for the film. Many of the musicians featured, for example Rob Zombie, Rage Against the Machine and Marilyn Manson, had also appeared on the soundtrack for The Matrix. Rob Dougan also re-contributed, licensing the instrumental version of "Furious Angels", as well as being commissioned to provide an original track, ultimately scoring the battle in the Merovingian's chateau. A remixed version of "Slap It" by electronic artist Fluke - listed on the soundtrack as "Zion" - was used during the rave scene.

Linkin Park contributed their instrumental song "Session" to the film as well, although it did not appear during the course of the film. P.O.D. composed a song called "Sleeping Awake", with a music video which focused heavily on Neo, as well as many images that were part of the film. Both songs played during the film's credits.

Reception

Box office

The film earned an estimated $5 million during Wednesday night previews in North America. The Matrix Reloaded grossed $37,508,303 on its Thursday opening day in North America from 3,603 theaters, which was the second highest opening day after Spider-Man's $39.4 millon and highest for a Thursday. It earned an additional $91,774,413 from its Friday to Sunday run while in 3,603 theaters. which was then beaten by Jim Carrey's Bruce Almighty. Ultimately, the film grossed $281.5 million in the US, and $742.1 million worldwide.[2]

Critical response

Reloaded had mostly positive critical reception, with a Rotten Tomatoes approval rating of 73%.[10] The film's average critic score on Metacritic is 63/100.[11] However, Entertainment Weekly named it as one of "The 25 Worst Sequels Ever Made".[12]

Some positive comments from critics included commendation for the quality and intensity of its action sequences,[13] and its intelligence.[14] Tony Toscano of Talking Pictures had high praise for the film, saying that "its character development and writing...is so crisp it crackles on the screen" and that "Matrix Reloaded re-establishes the genre and even raises the bar a notch or two" above the first film, The Matrix.[15]

On the other hand, negative comments included the sentiment that the plot was alienating,[16][17] with some critics regarding the focus on the action as a detriment to the film's human elements.[18][19] Some critics thought that the number of scenes with expository dialog worked against the film,[20] and the many unresolved subplots, as well as the cliffhanger ending, were also criticized.[21]

Awards

Controversy

The film was initially banned in Egypt, because of the violent content, and because it put into question issues about human creation "linked to the three monotheistic religions that we respect and which we believe in".[22] The Egyptian media claimed the film promoted Zionism, as it talks about Zion and the dark forces that wish to destroy it. However, it was eventually allowed to be shown in theaters, and was later released on VHS and DVD.[citation needed]

See also

References

- ^ Allmovie. 2010a. The Matrix Reloaded. [Online] Rovi Corporation (Updated 2010) Available at: http://www.allmovie.com/movie/the-matrix-reloaded-v279420 [Accessed 19 February 2010]. Archived at http://www.webcitation.org/5nfH2gABv.

- ^ a b c "The Matrix Reloaded (2003)". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved 2009-02-05.

- ^ "Festival de Cannes: The Matrix Reloaded". festival-cannes.com. Retrieved 2009-11-10.

- ^ "Aaliyah". The Independent. London. August 27, 2001. Archived from the original on 2010-06-06.

- ^ August 27, 2001 (2001-08-27). "Aaliyah: A 'beautiful person's' life cut short". Archives.cnn.com. Retrieved 2012-07-11.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Job, Ann. "Chasing the Stars: Carmakers in Movies". MSN.com. Retrieved 2005-01-30.

- ^ "Hollywood smog an inconvenient truth". Associated Press (CNN.com). November 14, 2006. Archived from the original on December 15, 2006.

- ^ "Movie connections for The Matrix Reloaded (2003)". Internet Movie Database (IMDB.com). February 16, 2010.

- ^ a b Silberman, Steve. "Matrix2". Wired. Retrieved December 25, 2012.

- ^ "The Matrix Reloaded Movie Reviews, Pictures". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved 2012-07-11.

- ^ "The Matrix Reloaded: Reviews". Metacritic. 2003-05-15. Retrieved 2012-07-11.

- ^ "The 25 Worst Sequels Ever Made – EW.com". Entertainment Weekly.

- ^ McCarthy, Todd (May 7, 2003). "The Matrix Reloaded". Variety. Retrieved 2007-07-12.

- ^ William Arnold (May 14, 2003). "'Matrix' fans can't afford to miss 'Reloaded'". Seattlepi.com. Retrieved 2007-07-12.

- ^ Tony Toscano (May 20, 2003). "The Matrix Reloaded (2003) movie review". Rotten Tomatoes. Archived from the original on 2009-02-20. Retrieved 2007-07-12.

- ^ Richard Schickel (May 11, 2003). "The Matrix Reboots". TIME. Retrieved 2007-07-12.

- ^ Rene Rodriguez (May 14, 2003). "Sequelitis infects 'Matrix Reloaded' with talk - lots of it". MiamiHerald.com. Archived from the original on 2003-08-12. Retrieved 2007-07-12.

- ^ David Sterritt (May 16, 2003). "Ready for a Neo world order?". csmonitor.com. Retrieved 2007-07-12.

- ^ Nathan Rabin (May 13, 2003). "The Matrix Reloaded review". A.V. Club. Retrieved 2007-07-12.

- ^ "The Austin Chronicle". The Austin Chronicle. 2012-07-06. Retrieved 2012-07-11.

- ^ Mark Caro (June 11, 2003). "Movie review: 'The Matrix Reloaded'". metromix.com. Archived from the original on 2007-12-30. Retrieved 2007-07-12.

- ^ "Egypt bans 'too religious' Matrix". BBC News. June 11, 2003. Retrieved 2007-07-12.

External links

- 2003 films

- American films

- English-language films

- 2000s action films

- 2000s science fiction films

- American action films

- American science fiction action films

- American action thriller films

- Cyberpunk films

- Martial arts science fiction films

- Films about telepresence

- Films directed by The Wachowskis

- Films shot in Australia

- Films shot in Sydney

- French-language films

- Gun fu films

- Kung fu films

- Martial arts films

- The Matrix (franchise)

- Science fiction action films

- Sequel films

- Silver Pictures films

- Village Roadshow Pictures films

- Warner Bros. films

- Screenplays by The Wachowskis