Breast implant: Difference between revisions

→Implants and mammography: Correcting to use proper terminology |

Otto Placik (talk | contribs) →Implants and mammography: Factual corrections to the text -- correct study titles, deleted weasel words. |

||

| Line 153: | Line 153: | ||

==Implants and mammography== |

==Implants and mammography== |

||

| ⚫ | The presence of [[radiology|radiologically]] opaque breast implants (either saline or silicone) might interfere with the radiographic sensitivity of the [[mammograph]], that is, the image might not show any tumor(s) present. In which case, an '''Eklund view mammogram''' is required to ascertain either the presence or the absence of a cancerous tumor, wherein the breast implant is manually displaced against the chest wall and the breast is pulled forward, so that the mammograph can visualize a greater volume of the the internal tissues; nonetheless, approximately one-third of the breast tissue remains inadequately visualized, resulting in an increased incidence of mammograms with false-negative results.<ref name="Handel1992">{{cite journal | author=Handel, N., Silverstein, M. J., Gamagami, P., Jensen, J. A., and Collins, A. | title=Factors Affecting Mammographic Visualization of the Breast after Augmentation Mammaplasty| journal=JAMA| year=1992| pages=1913–1917 | pmid=1404718 | doi=10.1001/jama.268.14.1913 | volume=268 | issue=14}}</ref> |

||

[[Image:Mammo breast cancer.jpg|thumb|right| |

[[Image:Mammo breast cancer.jpg|thumb|right|300px|'''Breast implant:''' <br> A mammograph of a normal breast (left);a mammograph of a cancerous breast (right).]] |

||

The [[breast cancer]] studies '' Cancer in the Augmented Breast: Diagnosis and Prognosis'' (1993) and ''Breast Cancer after Augmentation Mammoplasty'' (2001) of women with breast-implant prostheses reported no significant differences in disease-stage at the time of the diagnosis of cancer; prognoses are similar in both groups of women, with augmented patients at a lower risk for subsequent cancer recurrence or death.<ref name="Clark1993">{{cite journal | author=Clark CP 3rd, Peters GN, O'Brien KM. | title=Cancer in the Augmented Breast: Diagnosis and Prognosis| journal=Cancer | year=1993| pages=2170–4 | pmid=8374874 | doi=10.1002/1097-0142(19931001)72:7<2170::AID-CNCR2820720717>3.0.CO;2-1 | volume=72 | issue=7 }}</ref><ref name="Skinner2001">{{cite journal | author=Skinner KA, Silberman H, Dougherty W, Gamagami P, Waisman J, Sposto R, Silverstein MJ. | title=Breast cancer after augmentation mammoplasty| journal=Ann Surg Oncol. | year=2001| pages=138–44 | pmid=11258778 | doi=10.1007/s10434-001-0138-x | volume=8 | issue=2 }}</ref> Conversely, the use of implants for [[breast reconstruction]] ''after'' breast cancer [[mastectomy]] appears to have no negative effect upon the incidence of cancer-related death.<ref name="Lee2005">{{cite journal | author=Le GM, O'Malley CD, Glaser SL, Lynch CF, Stanford JL, Keegan TH, West DW. | title=Breast implants following mastectomy in women with early-stage breast cancer: prevalence and impact on survival| journal=Breast Cancer Res.| year=2005| pages=R184–93 | pmid=15743498 | doi=10.1186/bcr974 | volume=7 | issue=2 | pmc=1064128}}</ref> That patients with breast implants are more often diagnosed with palpable — but not larger — tumors indicates that equal-sized tumors might be more readily palpated in augmented patients, which might compensate for the impaired mammogram images.<ref name="Handel2006">{{cite journal | author=Handel N, Silverstein MJ | title=Breast cancer diagnosis and prognosis in augmented women| journal=Plastic Reconstructive Surgery | year=2006 | pages=587–93 | pmid=16932162 | doi=10.1097/01.prs.0000233038.47009.04 | volume=118 | issue=3 }}</ref> The ready palpability of the breast-cancer tumor(s) is consequent to breast tissue thinning by compression, innately in smaller breasts ''a priori'' (because they have lesser tissue volumes), and that the implant serves as a radio-opaque base against which a cancerous tumor can be differentiated.<ref name="Cunningham2006">{{cite journal | author=Cunningham B | title=Breast cancer diagnosis and prognosis in augmented women- Discussion| journal=Plastic Reconstructive Surgery | year=2006 | pages=594–595 | pmid=16932163 | doi=10.1097/01.prs.0000233047.87102.8e | volume=118 | issue=3 }}</ref> |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

The breast implant has no clinical bearing upon [[lumpectomy]] breast-conservation surgery for women who developed breast cancer after the implantation procedure, nor does the breast implant interfere with external beam radiation treatments (XRT); moreover, the post-treatment incidence of breast-tissue fibrosis is common, and thus a consequent increased rate of capsular [[contracture]].<ref name="Scwartz2006">{{cite journal | author=SChwartz GF | title=Consensus Conference on Breast Conservation| journal=JACAS | year=2006 | pages=198–207 | pmid=16864033 | volume=203 | issue=2 | doi=10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2006.04.009 | author-separator=, | display-authors=1 | last2=Veronesi | first2=U | last3=Clough | first3=K | last4=Dixon | first4=J | last5=Fentiman | first5=I | last6=Heywangkobrunner | first6=S | last7=Holland | first7=R | last8=Hughes | first8=K | last9=Mansel | first9=R }}</ref> The study ''Breast Cancer Detection and Survival among Women with Cosmetic Breast Implants: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Observational Studies'', reported a significant delay in the diagnoses of women who developed breast cancer after undergoing breast augmentation, when compared to breast cancer patients who had not undergone breast augmentation.<ref>Breast Cancer Detection and Survival among Women with Cosmetic Breast Implants: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Observational Studies. Lavigne, Holowaty, Pan, Villeneuve, Johnson, Fergusson, Morrison, and Brisson. BMJ (2013): n. pag. Web. <http://www.bmj.com/content/346/bmj.f2399>.</ref> The metadata study ''Breast Implants following Mastectomy in Women with Early-stage Breast Cancer: Prevalence and Impact on Survival'' (2005) reported that breast augmentation patients were statistically likelier to die from breast cancer. Although the use of implants for [[breast reconstruction]] ''after'' breast cancer [[mastectomy]] appears to have no negative effect upon the incidence of cancer-related death, women who underwent a mastectomy procedure tend to die earlier than women who underwent a lumpectomy procedure, with like diagnoses.<ref name="Lee2005">{{cite journal | author=Le GM, O'Malley CD, Glaser SL, Lynch CF, Stanford JL, Keegan TH, West DW. | title=Breast Implants following Mastectomy in Women with Early-stage Breast Cancer: Prevalence and Impact on Survival| journal=Breast Cancer Res.| year=2005| pages=R184–93 | pmid=15743498 | doi=10.1186/bcr974 | volume=7 | issue=2 | pmc=1064128}}</ref><ref>Hwang ES, et al. Survival after Lumpectomy and Mastectomy for Early stage Invasive Breast Cancer: The Effect of Age and Hormone receptor Status Cancer. 2013 April 1; 119(7); DOI: 10.1002/cncr.27795</ref> |

|||

==U.S. FDA approval== |

==U.S. FDA approval== |

||

Revision as of 07:16, 22 August 2013

A breast implant is a medical prosthesis used to augment, reconstruct, or create the physical form of breasts. Breast implants are applied to correct the size, form, and feel of a woman’s breasts in post–mastectomy breast reconstruction; for correcting congenital defects and deformities of the chest wall; for aesthetic breast augmentation; and for creating breasts in the male-to-female transsexual patient.

There are three general types of breast implant device, defined by the filler material: saline, silicone, and other. The saline implant has an elastomer silicone shell filled with sterile saline solution; the silicone implant has an elastomer silicone shell filled with viscous silicone gel; and the alternative implants have had silicone shells with other fillers, such as soy oil, polypropylene string, and peanut oil. Because of infections and other health problems, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration has not approved breast implants other than silicone and saline implants.

In surgical practice, for the reconstruction of a breast, the tissue expander device is a temporary breast prosthesis used to form and establish an implant pocket for the permanent breast implant. For the correction of male breast and chest-wall defects and deformities, the pectoral implant is the prosthesis used for the reconstruction and the aesthetic repair of a man’s chest. (See: gynecomastia and mastopexy)

History

- The 19th century

Since the late nineteenth century, breast implant devices have been used to surgically augment the size (volume), modify the shape (contour), and enhance the feel (tact) of a woman’s breasts. In 1895, surgeon Vincenz Czerny effected the earliest breast implant emplacement when he used the patient's autologous adipose tissue, harvested from a benign lumbar lipoma, to repair the asymmetry of the breast from which he had removed a tumor.[1] In 1889, surgeon Robert Gersuny experimented with paraffin injections, with disastrous results. From the first half of the twentieth century, physicians used other substances as breast implant fillers — ivory, glass balls, ground rubber, ox cartilage, Terylene wool, gutta-percha, Dicora, polyethylene chips, Ivalon (polyvinyl alcohol – formaldehyde polymer sponge), a polyethylene sac with Ivalon, polyether foam sponge (Etheron), polyethylene tape (Polystan) strips wound into a ball, polyester (polyurethane foam sponge) Silastic rubber, and teflon-silicone prostheses.[2]

- The 20th century

In the mid-twentieth century, Morton I. Berson, in 1945, and Jacques Maliniac, in 1950, each performed flap-based breast augmentations by rotating the patient’s chest wall tissue into the breast to increase its volume. Furthermore, throughout the 1950s and the 1960s, plastic surgeons used synthetic fillers — including silicone injections received by some 50,000 women, from which developed silicone granulomas and breast hardening that required treatment by mastectomy.[3] In 1961, the American plastic surgeons Thomas Cronin and Frank Gerow, and the Dow Corning Corporation, developed the first silicone breast prosthesis, filled with silicone gel; in due course, the first augmentation mammoplasty was performed in 1962 using the Cronin–Gerow Implant, prosthesis model 1963. In 1964, the French company Laboratoires Arion developed and manufactured the saline breast implant, filled with saline solution, and then introduced for use as a medical device in 1964.[4]

Types of breast implant device

- There are three types of breast implants:

- saline implant filled with sterile saline solution.

- silicone implant filled with viscous silicone gel.

- alternative-composition implant with various fillers (e.g. soy oil, polypropylene string, etc.) that are no longer manufactured because of their risks to patients.

- I. — Saline implants

The saline breast implant is filled with saline solution. The early models were prone to failure, including shell breakage, leakage of the saline filler, and deflation of the prosthesis. Contemporary models of saline breast implant are made with stronger, room-temperature vulcanized (RTV) shells made of a silicone elastomer. In the 1990s, in the U.S., the saline breast implant were more popular for breast prosthesis applied for breast augmentation, given the unavailability of silicone implants, because of the safety concerns of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

- Surgical technique

The saline breast implant was developed because of concerns about silicone gel and to make it possible to use a smaller surgical incision.[5] After placing the empty breast implants into the implant pockets, the plastic surgeon then fills each breast prosthesis with saline solution, and, since the implant was deflated, the incision scars will be smaller than for silicone-gel implants, which are all filled before surgery. Compared to silicone breast implants, saline implants are more likely to cause cosmetic problems such as rippling, wrinkling, and being noticeable to the eye and to the touch. This is especially true for women with very little breast tissue, and for post-mastectomy reconstruction patients. In the case of the woman with much breast tissue, saline breast implants can create the “look” of breasts (though not feel), much like the silicone implant.[6]

- II. — Silicone gel implants

As a medical device technology, there are five (5) generations of silicone breast implant, each defined by common model-manufacturing techniques.

- First generation

The Cronin–Gerow Implant, prosthesis model 1963, was a tear-drop-shaped sac (silicone rubber envelope) filled with viscous silicone-gel. To reduce the rotation of the emplaced breast-implant upon the chest wall, it was affixed to the implant pocket with a fastener-patch of Dacron material (Polyethylene terephthalate) attached to the rear of the breast implant shell.[7]

- Second generation

In the 1970s, the first technological development, a thinner device-shell and a thinner, low-cohesion silicone-gel filler, improved the functionality and verisimilitude (size, look, and feel) of the silicone breast implant. Yet, in clinical practice, the second-generation proved fragile, and suffered greater incidences of shell rupture, and of “silicone gel bleed” (filler leakage through an intact shell). The consequent, increased incidence-rates of medical complications (e.g. capsular contracture) precipitated U.S. government faulty-product class action-lawsuits against the Dow Corning Corporation, and other manufacturers of prosthetic breast prostheses.

- The second technological development was a polyurethane foam coating for the implant shell; it reduced the incidence of capsular contracture by causing an inflammatory reaction that impeded the formation of a capsule of fibrous collagen tissue around the breast implant. Nevertheless, the medical use of polyurethane-coated breast implants was briefly discontinued because of the potential health-risk posed by 2,4-toluenediamine (TDA), a carcinogenic by-product of the chemical breakdown of the implant’s polyurethane foam coating.[8] After reviewing the medical data, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration concluded that TDA-induced breast cancer was an infinitesimal health-risk to women with breast implants, and did not justify legally requiring physicians to explain the matter to their patients. In the event, polyurethane-coated breast implants remain in plastic surgical practice in Europe and in South America; in the U.S., no breast implant manufacturer has sought the FDA’s approval for American medical sale.[9]

- The third technological development was the double lumen breast-implant, a double-cavity device composed of a silicone-implant within a saline-implant. The two-fold, technical goal was: (i) the cosmetic benefits of silicone-gel (the inner lumen) enclosed in saline solution (the outer lumen); (ii) a breast-implant device the volume of which is post-operatively adjustable. Nevertheless, the more complex design of the double-lumen breast-implant suffered a device-failure rate greater than that of single-lumen breast implants. The contemporary versions of Second generation devices, presented in 1984, are the “Becker Expandable” models of breast implant device, used primarily for breast reconstruction.

- Third and Fourth generations

In the 1980s, the models of the Third and of the Fourth generations of breast-implant devices were sequential advances in manufacturing technology, e.g. elastomer-coated shells that decreased gel-bleed (filler leakage), and a thicker filler (increased-cohesion) gel. Sociologically, the manufacturers then designed and fabricated varieties of anatomic models (natural breast) and shaped models (round, tapered) that realistically corresponded with the breast and body types presented by women patients. The tapered models of breast implant have a uniformly textured surface, to reduce rotation; the round models of breast implant are available in smooth-surface and textured-surface types.

- Fifth generation

Since the mid-1990s, the Fifth generation of silicone breast implant is made of a semi-solid gel that mostly eliminates filler leakage (silicone gel bleed) and silicone migration from the breast to elsewhere in the body. The studies Experience with Anatomical Soft Cohesive Silicone gel Prosthesis in Cosmetic and Reconstructive Breast Implant Surgery (2004) and Cohesive Silicone gel Breast Implants in Aesthetic and Reconstructive Breast Surgery (2005) reported low incidence rates of capsular contracture and of device-shell rupture, improved medical safety and technical efficacy greater than earlier generations of breast implant device.[10][11][12]

The patient

- Psychology

The breast augmentation patient usually is a young woman whose personality profile indicates psychological distress about her personal appearance and her body (self image), and a history of having endured criticism (teasing) about the aesthetics of her person.[13] The studies Body Image Concerns of Breast Augmentation Patients (2003) and Body Dysmorphic Disorder and Cosmetic Surgery (2006) reported that the woman who underwent breast augmentation surgery also had undergone psychotherapy, suffered low self-esteem, presented frequent occurrences of psychological depression, had attempted suicide, and suffered body dysmorphia, a type of mental illness. Post-operative patient surveys about mental health and quality-of-life, reported improved physical health, physical appearance, social life, self-confidence, self-esteem, and satisfactory sexual functioning. Furthermore, the women reported long-term satisfaction with their breast implant outcomes; some despite having suffered medical complications that required surgical revision, either corrective or aesthetic. Likewise, in Denmark, 8.0 per cent of breast augmentation patients had a pre-operative history of psychiatric hospitalization.[14][15][16][17][18][19][20][21][22]

- Mental health

In 2008, the longitudinal study Excess Mortality from Suicide and other External Causes of Death Among Women with Cosmetic Breast Implants (2007), reported that women who sought breast implants are almost 3.0 times as likely to commit suicide as are women who have not sought breast implants. Compared to the standard suicide-rate for women of the general populace, the suicide-rate for women with augmented breasts remained constant until 10-years post-implantation, yet, it increased to 4.5 times greater at the 11-year mark, and so remained until the 19-year mark, when it increased to 6.0 times greater at 20-years post-implantation. Moreover, additional to the suicide-risk, women with breast implants also faced a trebled death-risk from alcoholism and the abuse of prescription and recreational drugs.[23][24] Although seven studies have statistically connected a woman’s breast augmentation to a greater suicide-rate, the research indicates that breast augmenation surgery does not increase the death rate; and that, in the first instance, it is the psychopathologically-inclined woman who is likelier to undergo a breast augmentation procedure.[25][26][27][28][29][30]

The study Effect of Breast Augmentation Mammoplasty on Self-Esteem and Sexuality: A Quantitative Analysis (2007), reported that the women attributed their improved self image, self-esteem, and increased, satisfactory sexual functioning to having undergone breast augmentation; the cohort, aged 21–57 years, averaged post-operative self-esteem increases that ranged from 20.7 to 24.9 points on the 30-point Rosenberg self-esteem scale, which data supported the 78.6 per cent increase in the woman’s libido, relative to her pre-operative level of libido.[31] Therefore, before agreeing to any surgery, the plastic surgeon evaluates and considers the woman’s mental health to determine if breast implants can positively affect her self-esteem and sexual functioning.

Surgical procedures

Indications

A mammoplasty procedure for the emplacement of breast implant devices has three (3) purposes:

- primary reconstruction — the replacement of breast tissues damaged by trauma (blunt, penetrating, blast), disease (breast cancer), and failed anatomic development (tuberous breast deformity).

- revision and reconstruction — to revise (correct) the outcome of a previous breast reconstruction surgery.

- primary augmentation — to aesthetically augment the size, form, and feel of the breasts.

The operating room (OR) time of post–mastectomy breast reconstruction, and of breast augmentation surgery is determined by the procedure employed, the type of incisions, the breast implant (type and materials), and the pectoral locale of the implant pocket.

Incision types

Breast implant emplacement is performed with five (5) types of surgical incisions:

- Inframammary — an incision made to the infra-mammary fold (IMF), which affords maximal access for precise dissection of the tissues and emplacement of the breast implants. It is the preferred surgical technique for emplacing silicone-gel implants, because it better exposes the breast tissue–pectoralis muscle interface; yet, IMF implantation can produce thicker, slightly more visible surgical scars.

- Periareolar — a border-line incision along the periphery of the areola, which provides an optimal approach when adjustments to the IMF position are required, or when a mastopexy (breast lift) is included to the primary mammoplasty procedure. In periareolar emplacement, the incision is around the medial-half (inferior half) of the areola’s circumference. Silicone gel implants can be difficult to emplace via periareolar incision, because of the short, five-centimetre length (~ 5.0 cm) of the required access-incision. Aesthetically, because the scars are at the areola’s border (periphery), they usually are less visible than the IMF-incision scars of women with light-pigment areolae; when compared to cutaneous-incision scars, the modified epithelia of the areolae are less prone to (raised) hypertrophic scars.

- Transaxillary — an incision made to the axilla (armpit), from which the dissection tunnels medially, to emplace the implants, either bluntly or with an endoscope (illuminated video microcamera), without producing visible scars on the breast proper; yet, it is likelier to produce inferior asymmetry of the implant-device position. Therefore, surgical revision of transaxillary emplaced breast implants usually requires either an IMF incision or a periareolar incision.

- Transumbilical — a trans-umbilical breast augmentation (TUBA) is a less common implant-device emplacement technique wherein the incision is at the umbilicus (navel), and the dissection tunnels superiorly, up towards the bust. The TUBA approach allows emplacing the breast implants without producing visible scars upon the breast proper; but makes appropriate dissection and device-emplacement more technically difficult. A TUBA procedure is performed bluntly — without the endoscope’s visual assistance — and is not appropriate for emplacing (pre-filled) silicone-gel implants, because of the great potential for damaging the elastomer silicone shell of the breast implant during its manual insertion through the short (~2.0 cm) incision at the navel, and because pre-filled silicone gel implants are incompressible, and cannot be inserted through so small an incision.[32]

- Transabdominal — as in the TUBA procedure, in the transabdominoplasty breast augmentation (TABA), the breast implants are tunneled superiorly from the abdominal incision into bluntly dissected implant pockets, whilst the patient simultaneously undergoes an abdominoplasty.[33]

Implant pocket placement

The four (4) surgical approaches to emplacing a breast implant to the implant pocket are described in anatomical relation to the pectoralis major muscle.

- Subglandular — the breast implant is emplaced to the retromammary space, between the breast tissue (the gland) and the pectoralis major muscle, which most approximates the plane of normal breast tissue, and affords the most aesthetic results. Yet, in women with thin pectoral soft-tissue, the subglandular position is likelier to show the ripples and wrinkles of the underlying implant. Moreover, the capsular contracture incidence rate is slightly greater with subglandular implantation.

- Subfascial — the breast implant is emplaced beneath the fascia of the pectoralis major muscle; this is a variant of the subglandular position.[34] The technical advantages of the subfascial implant-pocket technique are debated; proponent surgeons report that the layer of fascial tissue provides greater implant coverage and better sustains its position.[35]

- Subpectoral (dual plane) — the breast implant is emplaced beneath the pectoralis major muscle, after the surgeon releases the inferior muscular attachments, with or without partial dissection of the subglandular plane. Resultantly, the upper pole of the implant is partially beneath the pectoralis major muscle, while the lower pole of the implant is in the subglandular plane. This implantation technique achieves maximal coverage of the upper pole of the implant, whilst allowing the expansion of the implant’s lower pole; however, “animation deformity”, the movement of the implants in the subpectoral plane can be excessive for some patients.[36]

- Submuscular — the breast implant is emplaced beneath the pectoralis major muscle, without releasing the inferior origin of the muscle proper. Total muscular coverage of the implant can be achieved by releasing the lateral muscles of the chest wall — either the serratus muscle or the pectoralis minor muscle, or both — and suturing it, or them, to the pectoralis major muscle. In breast reconstruction surgery, the submuscular implantation approach effects maximal coverage of the breast implants.

Post-surgical recovery

The surgical scars of a breast augmentation mammoplasty develop approximately at 6-weeks post-operative, and fade within months. Depending upon the daily-life physical activities required of the woman, the breast augmentation patient usually resumes her normal life at 1-week post-operative. Moreover, women whose breast implants were emplaced beneath the chest muscles (submuscular placement) usually have a longer, slightly more painful convalescence, because of the healing of the incisions to the chest muscles. Usually, she does not exercise or engage in strenuous physical activities for approximately 6 weeks. During the initial post-operative recovery, the woman is encouraged to regularly exercise (flex and move) her arm to alleviate pain and discomfort; if required, analgesic indwelling medication catheters can alleviate pain.[37][38] Moreover, significantly improved patient recovery has resulted from refined breast-device implantation techniques (submuscular, subglandular) that allow 95 per cent of women to resume their normal lives at 24-hours post-procedure, without bandages, fluid drains, pain pumps, catheters, medical support brassières, or narcotic pain medication.[39][40][41][42]

Complications

The plastic surgical emplacement of breast-implant devices, either for breast reconstruction or for aesthetic purpose, presents the same health risks common to surgery, such as adverse reaction to anesthesia, hematoma (post-operative bleeding), seroma (fluid accumulation), incision-site breakdown (wound infection). Complications specific to breast augmentation include breast pain, altered sensation, impeded breast-feeding function, visible wrinkling, asymmetry, thinning of the breast tissue, and symmastia, the “bread loafing” of the bust that interrupts the natural plane between the breasts. Specific treatments for the complications of indwelling breast implants — capsular contracture and capsular rupture — are periodic MRI monitoring and physical examinations. Furthermore, complications and re-operations related to the implantation surgery, and to tissue expanders (implant place-holders during surgery) can cause unfavorable scarring in approximately 6–7 per cent of the patients. [43][44][45] Statistically, 20 per cent of women who underwent cosmetic implantation, and 50 per cent of women who underwent breast reconstruction implantation, required their explantation at the 10-year mark.[46]

Implant rupture

Because a breast implant is a Class III medical device of limited product-life, the principal rupture-rate factors are its age and design; nonetheless, a breast implant device can retain its mechanical integrity for decades in a woman’s body.[47] When a saline breast implant ruptures, leaks, and empties, it quickly deflates, and thus can be readily explanted (surgically removed). The follow-up report, Natrelle Saline-filled Breast Implants: a Prospective 10-year Study (2009) indicated rupture-deflation rates of 3–5 per cent at 3-years post-implantation, and 7–10 per cent rupture-deflation rates at 10-years post-implantation.[48] When a silicone breast implant ruptures it usually does not deflate, yet the filler gel does leak from it, which can migrate to the implant pocket; therefore, an intracapsular rupture (in-capsule leak) can become an extracapsular rupture (out-of-capsule leak), and each occurrence is resolved by explantation. Although the leaked silicone filler-gel can migrate from the chest tissues to elsewhere in the woman’s body, most clinical complications are limited to the breast and armpit areas, usually manifested as granulomas (inflammatory nodules) and axillary lymphadenopathy (enlarged lymph glands in the armpit area).[49][50][51]

The suspected mechanisms of breast-implant rupture are:

- damage during implantation

- damage during (other) surgical procedures

- chemical degradation of the breast implant shell

- trauma (blunt trauma, penetrating trauma, blast trauma)

- mechanical pressure of traditional mammographic breast examination [52]

Silicone implant rupture can be evaluated using MRI.[53] From the long-term MRI data for single-lumen breast implants, the European literature about Second generation silicone-gel breast implants (1970s design), reported silent device-rupture rates of 8–15 per cent at 10-years post-implantation (15–30% of the patients).[54][55][56] In 2009, a branch study of the U.S. FDA’s core clinical trials for primary breast augmentation surgery patients, reported low device-rupture rates of 1.1 per cent at 6-years post-implantation.[57] The first series of MRI evaluations of the silicone breast implants with thick filler-gel reported a device-rupture rate of 1.0 per cent, or less, at the median 6-year device-age.[58] Statistically, the manual examination (palpation) of the woman is inadequate for accurately evaluating if a breast implant has ruptured. The study, The Diagnosis of Silicone Breast-implant Rupture: Clinical Findings Compared with Findings at Magnetic Resonance Imaging (2005), reported that, in asymptomatic patients, only 30 per cent of the of ruptured breast implants is accurately palpated and detected by an experienced plastic surgeon, whereas MRI examinations accurately detected 86 per cent of breast-implant ruptures.[59] Thus, the U.S. FDA recommended scheduled MRI examinations, as silent-rupture screenings, beginning at the 3-year-mark post-implantation, and then every two years, thereafter.[43] Nonetheless, beyond the U.S., the medical establishments of other nations have not endorsed routine magnetic resonance image (MRI) screening, proposing that such a radiologic examination be reserved for two purposes: (i) for the woman with a suspected breast-implant rupture; and (ii) for the confirmation of mammographic and ultrasonic studies that indicate the presence of a ruptured breast implant.[60] Furthermore, The Effect of Study design Biases on the Diagnostic Accuracy of Magnetic Resonance Imaging for Detecting Silicone Breast Implant Ruptures: a Meta-analysis (2011) reported that the breast-screening MRIs of asymptomatic women might be overestimating the incidence of breast-implant rupture.[61] Nonetheless, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration emphasised that “breast implants are not lifetime devices. The longer a woman has silicone gel-filled breast implants, the more likely she is to experience complications.”[62]

Capsular contracture

The human body’s immune response to a surgically installed foreign object — breast implant, cardiac pacemaker, orthopedic prosthesis — is to encapsulate it with scar tissue capsules of tightly woven collagen fibers, in order to maintain the integrity of the body by isolating the foreign object, and so tolerate its presence. Capsular contracture — which should be distinguished from normal capsular tissue — occurs when the collagen-fiber capsule thickens and compresses the breast implant; it is a painful complication that might distort either the breast implant, or the breast, or both. The cause of capsular contracture is unknown, but the common incidence factors include bacterial contamination, device-shell rupture, filler leakage, and hematoma. The surgical implantation procedures that have reduced the incidence of capsular contracture include submuscular emplacement, the use of breast implants with a textured surface (polyurethane-coated);[63][64][65] limited pre-operative handling of the implants, limited contact with the chest skin of the implant pocket before the emplacement of the breast implant, and irrigation of the recipient site with triple-antibiotic solutions.[66][67]

The correction of capsular contracture might require an open capsulotomy (surgical release) of the collagen-fiber capsule, or the removal, and possible replacement, of the breast implant. Furthermore, in treating capsular contracture, the closed capsulotomy (disruption via external manipulation) once was a common maneuver for treating hard capsules, but now is a discouraged technique, because it can rupture the breast implant. Non-surgical treatments for collagen-fiber capsules include massage, external ultrasonic therapy, leukotriene pathway inhibitors such as zafirlukast (Accolate) or montelukast (Singulair), and pulsed electromagnetic field therapy (PEMFT).[68][69][70][71]

Repair and revision surgeries

When the woman is unsatisfied with the outcome of the augmentation mammoplasty; or when technical or medical complications occur; or because of the breast implants’ limited product life (Class III medical device, in the U.S.), it is likely she might require replacing the breast implants. The common revision surgery indications include major and minor medical complications, capsular contracture, shell rupture, and device deflation.[52] Revision incidence rates were greater for breast reconstruction patients, because of the post-mastectomy changes to the soft-tissues and to the skin envelope of the breast, and to the anatomical borders of the breast, especially in women who received adjuvant external radiation therapy.[52] Moreover, besides breast reconstruction, breast cancer patients usually undergo revision surgery of the nipple-areola complex (NAC), and symmetry procedures upon the opposite breast, to create a bust of natural appearance, size, form, and feel. Carefully matching the type and size of the breast implants to the patient’s pectoral soft-tissue characteristics reduces the incidence of revision surgery. Appropriate tissue matching, implant selection, and proper implantation technique, the re-operation rate was 3.0 per cent at the 7-year-mark, compared with the re-operation rate of 20 per cent at the 3-year-mark, as reported by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration.[72][73]

Alleged complications

Systemic disease and sickness

Since the 1990s, reviews of the studies that sought causal links between silicone-gel breast implants and systemic disease reported no link between the implants and subsequent systemic and autoimmune diseases.[60][74][75][76] Nonetheless, during the 1990s, thousands of women claimed sicknesses they believed were caused by their breast implants, including neurological and rheumatological health problems.

In the study Long-term Health Status of Danish Women with Silicone Breast Implants (2004), the national healthcare system of Denmark reported that women with implants did not risk a greater incidence and diagnosis of autoimmune disease, when compared to same-age women in the general population; that the incidence of musculoskeletal disease was lower among women with breast implants than among women who had undergone other types of cosmetic surgery; and that they had a lower incidence rate than like women in the general population.[77][78]

Follow-up longitudinal studies of these breast implant patients confirmed the previous findings on the matter.[79] European and North American studies reported that women who underwent augmentation mammoplasty, and any plastic surgery procedure, tended to be healthier and wealthier than the general population, before and after implantation; that plastic surgery patients had a lower standardized mortality ratio than did patients for other surgeries; yet faced an increased risk of death by lung cancer than other plastic surgery patients. Moreover, because only one study, the Swedish Long-term Cancer Risk Among Swedish Women with Cosmetic Breast Implants: an Update of a Nationwide Study (2006), controlled for tobacco smoking information, the data were insufficient to establish verifiable statistical differences between smokers and non-smokers that might contribute to the higher lung cancer mortality rate of women with breast implants.[80][81] The long-term study of 25,000 women, Mortality among Canadian Women with Cosmetic Breast Implants (2006), reported that the “findings suggest that breast implants do not directly increase mortality in women.”[82]

A 2001 study, Silicone gel Breast Implant Rupture, Extracapsular Silicone, and Health Status in a Population of Women, reported increased incidences of fibromyalgia among women who suffered extracapsular silicone-gel leakage than among women whose breast implants neither ruptured nor leaked.[83] The study later was criticized as significantly methodologically flawed, and a number of large subsequent follow-up studies have not shown any evidence of a causal device–disease association. After investigating, the U.S. FDA has concluded “the weight of the epidemiological evidence published in the literature does not support an association between fibromyalgia and breast implants.”.[84][85] Recent systemic review by Lipworth (2011)[86] concludes that "any claims that remain regarding an association between cosmetic breast implants and CTDs are not supported by the scientific literature".

Platinum toxicity

The manufacture of silicone breast implants requires the metallic element platinum as a catalyst to accelerate the transformation of silicone oil into silicone gel for making the elastomer silicone shells, and for making other medical-silicone devices.[87] The literature indicates that trace quantities of platinum leak from such types of silicone breast implant; therefore, platinum is present in the surrounding pectoral tissue(s). The rare pathogenic consequence is an accumulation of platinum in the bone marrow, from where blood cells might deliver it to nerve endings, thus causing nervous system disorders such as blindness, deafness, and nervous tics (involuntary muscle contractions).[87] In 2002, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration reviewed the studies on the human biological effects of breast-implant platinum, and reported little causal evidence of platinum toxicity to women with breast implants.[88] Furthermore, in the journal Analytical Chemistry, the study Total Platinum Concentration and Platinum Oxidation States in Body Fluids, Tissue, and Explants from Women Exposed to Silicone and Saline Breast Implants by IC-ICPMS (2006), proved controversial for claiming to have identified previously undocumented toxic platinum oxidative states in vivo.[89] Later, in a letter to the readers, the editors of Analytical Chemistry published their concerns about the faulty experimental design of the study, and warned readers to “use caution in evaluating the conclusions drawn in the paper.”[90] Furthermore, after reviewing the research data of the study, and other pertinent literature, the U.S. FDA reported that the data do not support the findings presented; that the platinum used, in new-model breast-implant devices, likely is not ionized, and therefore is not a significant risk to the health of the women.[91]

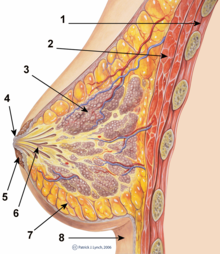

Implants and breast-feeding

1. Chest wall

2. Pectoralis muscles

3. Lobules

4. Nipple

5. Areola

6. Milk duct

7. Fatty tissue

8. Skin envelope

- The functional breast

The breasts are apocrine glands that produce milk for the feeding of infant children; each breast has a nipple within an areola (nipple-areola complex, NAC), the skin color of which varies from pink to dark brown, and has sebaceous glands. Within the mammary gland, the lactiferous ducts produce breast milk, and are distributed throughout the breast, with two-thirds of the tissue within 30-mm of the base of the nipple. In each breast, 4–18 lactiferous ducts drain to the nipple; the glands-to-fat ratio is 2:1 in lactating women, and to 1:1 in non-lactating women; besides milk glands, the breast is composed of connective tissue (collagen, elastin), adipose tissue (white fat), and the suspensory Cooper's ligaments. The peripheral nervous system innervation of the breast is by the anterior and lateral cutaneous branches of the fourth-, fifth-, and sixth intercostal nerves, while the Thoracic spinal nerve 4 (T4) innervating the dermatomic area supplies sensation to the nipple-areola complex.[92][93]

Digestive contamination and systemic toxicity are the principal infant-health concerns; the leakage of breast implant filler to the breast milk, and if the filler is dangerous to the nursing infant. Breast implant device fillers are biologically inert — saline filler is salt water, and silicone filler is indigestible — because each substance is chemically inert, and environmentally common. Moreover, proponent physicians have said there “should be no absolute contraindication to breast-feeding by women with silicone breast implants.”[94][95] In the early 1990s, at the beginning of the silicone breast-implant sickness occurrences, small-scale, non-random studies (i.e. “patients came with complaints, which might have many sources”, not “doctors performed random tests”) indicated possible breast-feeding complications from silicone implants; yet no study reported device–disease causality.[95]

- The augmented breast

Women with breast implants may have functional breast-feeding difficulties; mammoplasty procedures that feature periareolar incisions are especially likely to cause breast-feeding difficulties. Surgery may also damage the lactiferous ducts and the nerves in the nipple-areola area.[96][97][98]

Functional breast-feeding difficulties arise if the surgeon cut the milk ducts or the major nerves innervating the breast, or if the milk glands were otherwise damaged. Milk duct and nerve damage are more common if the incisions cut tissue near the nipple. The milk glands are most likely to be affected by subglandular implants (under the gland), and by large-sized breast implants, which pinch the lactiferous ducts and impede milk flow. Small-sized breast implants, and submuscular implantation, cause fewer breast-function problems; however, it is impossible to predict whether a woman who undergoes breast augmentation will be able to successfully breast feed since some women are able to breast-fed after periareolarincisions and subglandular placement and some are not able to after augmentation using submuscular and other types of incisions.[98]

Implants and mammography

The presence of radiologically opaque breast implants (either saline or silicone) might interfere with the radiographic sensitivity of the mammograph, that is, the image might not show any tumor(s) present. In which case, an Eklund view mammogram is required to ascertain either the presence or the absence of a cancerous tumor, wherein the breast implant is manually displaced against the chest wall and the breast is pulled forward, so that the mammograph can visualize a greater volume of the the internal tissues; nonetheless, approximately one-third of the breast tissue remains inadequately visualized, resulting in an increased incidence of mammograms with false-negative results.[99]

A mammograph of a normal breast (left);a mammograph of a cancerous breast (right).

The breast cancer studies Cancer in the Augmented Breast: Diagnosis and Prognosis (1993) and Breast Cancer after Augmentation Mammoplasty (2001) of women with breast-implant prostheses reported no significant differences in disease-stage at the time of the diagnosis of cancer; prognoses are similar in both groups of women, with augmented patients at a lower risk for subsequent cancer recurrence or death.[100][101] Conversely, the use of implants for breast reconstruction after breast cancer mastectomy appears to have no negative effect upon the incidence of cancer-related death.[102] That patients with breast implants are more often diagnosed with palpable — but not larger — tumors indicates that equal-sized tumors might be more readily palpated in augmented patients, which might compensate for the impaired mammogram images.[65] The ready palpability of the breast-cancer tumor(s) is consequent to breast tissue thinning by compression, innately in smaller breasts a priori (because they have lesser tissue volumes), and that the implant serves as a radio-opaque base against which a cancerous tumor can be differentiated.[103]

The breast implant has no clinical bearing upon lumpectomy breast-conservation surgery for women who developed breast cancer after the implantation procedure, nor does the breast implant interfere with external beam radiation treatments (XRT); moreover, the post-treatment incidence of breast-tissue fibrosis is common, and thus a consequent increased rate of capsular contracture.[104] The study Breast Cancer Detection and Survival among Women with Cosmetic Breast Implants: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Observational Studies, reported a significant delay in the diagnoses of women who developed breast cancer after undergoing breast augmentation, when compared to breast cancer patients who had not undergone breast augmentation.[105] The metadata study Breast Implants following Mastectomy in Women with Early-stage Breast Cancer: Prevalence and Impact on Survival (2005) reported that breast augmentation patients were statistically likelier to die from breast cancer. Although the use of implants for breast reconstruction after breast cancer mastectomy appears to have no negative effect upon the incidence of cancer-related death, women who underwent a mastectomy procedure tend to die earlier than women who underwent a lumpectomy procedure, with like diagnoses.[102][106]

U.S. FDA approval

In 1988, twenty-six years after the 1962 introduction of breast implants filled with silicone gel, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) investigated breast-implant failures and the subsequent complications, and re-classified breast implant devices as Class III medical devices, and required from manufacturers the documentary data substantiating the safety and efficacy of their breast implant devices.[107] In 1992, the FDA placed silicone-gel breast implants in moratorium in the U.S., because there was “inadequate information to demonstrate that breast implants were safe and effective”. Nonetheless, medical access to silicone-gel breast implant devices continued for clinical studies of post-mastectomy breast reconstruction, the correction of congenital deformities, and the replacement of ruptured silicone-gel implants. The FDA required from the manufacturers the clinical trial data, and permitted their providing breast implants to the breast augmentation patients for the statistical studies required by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration.[107] In mid–1992, the FDA approved an adjunct study protocol for silicone-gel filled implants for breast reconstruction patients, and for revision-surgery patients. Also in 1992, the Dow Corning Corporation, a silicone products and breast-implant manufacturer, announced the discontinuation of five implant-grade silicones, but would continue producing 45 other, medical-grade, silicone materials—three years later, in 1995, the Dow Corning Corporation went bankrupt when it faced 19,000 breast-implant sickness lawsuits.[107]

- In 1997, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) appointed the Institute of Medicine (IOM) of the U.S. National Academy of Sciences (NAS) to investigate the potential risks of operative and post-operative complications from the emplacement of silicone breast implants. The IOM’s review of the safety and efficacy of silicone gel-filled breast implants, reported that the “evidence suggests diseases or conditions, such as connective tissue diseases, cancer, neurological diseases, or other systemic complaints or conditions are no more common in women with breast implants, than in women without implants”; subsequent studies and systemic review found no causal link between silicone breast implants and disease.[107]

- In 1998, the U.S. FDA approved adjunct study protocols for silicone-gel filled implants only for breast reconstruction patients and for revision-surgery patients; and also approved the Dow Corning Corporation’s Investigational Device Exemption (IDE) study for silicone-gel breast implants for a limited number of breast augmentation-, reconstruction-, and revision-surgery patients.[107]

- In 1999, the Institute of Medicine published the Safety of Silicone Breast Implants (1999) study that reported no evidence that saline-filled and silicone-gel filled breast implant devices caused systemic health problems; that their use posed no new health or safety risks; and that local complications are “the primary safety issue with silicone breast implants”, in distinguishing among routine and local medical complications and systemic health concerns.”[107][108][109]

- In 2000, the FDA approved saline breast implant Premarket Approval Applications (PMA) containing the type and rate data of the local medical complications experienced by the breast surgery patients.[110] “Despite complications experienced by some women, the majority of those women still in the Inamed Corporation and Mentor Corporation studies, after three years, reported being satisfied with their implants.”[107] The premarket approvals were granted for breast augmentation, for women at least 18 years old, and for women requiring breast reconstruction.[111][112]

- In 2006, for the Inamed Corporation and for the Mentor Corporation, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration lifted its restrictions against using silicone-gel breast implants for breast reconstruction and for augmentation mammoplasty. Yet, the approval was conditional upon accepting FDA monitoring, the completion of 10-year-mark studies of the women who already had the breast implants, and the completion of a second, 10-year-mark study of the safety of the breast implants in 40,000 other women.[113] The FDA warned the public that breast implants do carry medical risks, and recommended that women who undergo breast augmentation should periodically undergo MRI examinations to screen for signs of either shell rupture or of filler leakage, or both conditions; and ordered that breast surgery patients be provided with detailed, informational brochures explaining the medical risks of using silicone-gel breast implants.[107]

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration established the age ranges for women seeking breast implants; for breast reconstruction, silicone-gel filled implants and saline-filled implants were approved for women of all ages; for breast augmentation, saline implants were approved for women 18 years of age and older; silicone implants were approved for women 22 years of age and older. [4]. Because each breast implant device entails different medical risks, the minimum age of the patient for saline breast implants is different from the minimum age of the patient for silicone breast implants — because of the filler leakage and silent shell-rupture risks; thus, periodic MRI screening examinations are the recommended post-operative, follow-up therapy for the patient. [5] In other countries, in Europe and Oceania, the national health ministries’ breast-implant policies do not endorse periodic MRI screening of asymptomatic patients, but suggest palpation proper — with or without an ultrasonic screening — to be sufficient post-operative therapy for most patients.

Criticism

In the early 1990s, the national health ministries of the listed countries reviewed the pertinent studies for causal links among silicone-gel breast implants and systemic and auto-immune diseases. The collective conclusion is that there is no evidence establishing a causal connection between the implantation of silicone breast implants and either type of disease. The affected women complained of systemic disease manifested as fungal, neurologic, and rheumatologic ailments. The Danish study Long-term Health Status of Danish Women with Silicone Breast Implants (2004) reported that women who had breast implants for an average of 19 years were no more likely to report an excessive number of rheumatic disease symptoms than would the women of the control group.[77] The follow-up study Mortality Rates Among Augmentation Mammoplasty Patients: An Update (2006) reported a decreased standardized mortality ratio and an increased risk of lung cancer death among breast-implant patients, than among patients for other types of plastic surgery; the mortality rate differences were attributed to tobacco smoking.[114] The study Mortality Among Canadian Women with Cosmetic Breast Implants (2006), about some 25,000 women with breast implants, reported a 43 per cent lower rate of breast cancer among them than among the general populace, and a lower-than-average risk of cancer.[82]

| Year | Country | Systemic Review Group | Conclusions |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1991–93 | United Kingdom | Independent Expert Advisory Group (IEAG) | There was no evidence of an increased risk of connective-tissue disease in patients who had undergone silicone-gel breast implant emplacement, and no cause for changing either breast implant practice or policy in the U.K. |

| 1996 | United States | U.S. Institute of Medicine (IOM)[115] | There was “insufficient evidence for an association of silicone gel- or saline-filled breast implants with defined connective tissue disease”. |

| 1996 | France | Agence Nationale pour le Developpement de l’Evaluation Medicale (ANDEM) [National Agency for Medical Development and Evaluation] [116] | French original: “Nous n’avons pas observé de connectivite ni d’autre pathologie auto-immune susceptible d’être directement ou indirectement induite par la présence d’un implant mammaire en particulier en gel de silicone. . . .”

English translation: “We did not observe connective tissue diseases to be directly or indirectly associated with (in particular) silicone-gel breast implants. . . .” |

| 1997 | Australia | Therapeutic Devices Evaluation Committee (TDEC) | The “current, high-quality literature suggest that there is no association between breast implants and connective tissue disease-like syndromes (atypical connective tissue diseases).”[117] |

| 1998 | Germany | Federal Institute for Medicine and Medical Products | Reported that “silicone breast implants neither cause auto-immune diseases nor rheumatic diseases and have no disadvantageous effects on pregnancy, breast-feeding capability, or the health of children who are breast-fed. There is no scientific evidence for the existence of silicone allergy, silicone poisoning, atypical silicone diseases or a new silicone disease.”[118] |

| 2000 | United States | Federal court-ordered review[119] | “No evidence of an association between . . . silicone-gel-filled breast implants specifically, and any of the individual CTDs, all definite CTDs combined, or other auto-immune or rheumatic conditions.” |

| 2000 | European Union | European Committee on Quality Assurance & Medical Devices in Plastic Surgery (EQUAM) | “Additional medical studies have not demonstrated any association between silicone-gel filled breast implants and traditional auto-immune or connective tissue diseases, cancer, nor any other malignant disease. . . . EQUAM continues to believe that there is no scientific evidence that silicone allergy, silicone intoxication, atypical disease or a ‘new silicone disease’ exists.”[120] |

| 2001 | United Kingdom | UK Independent Review Group (UK-IRG) | “There is no evidence of an association with an abnormal immune response or typical or atypical connective tissue diseases or syndromes.”[121] |

| 2001 | United States | Court-appointed National Science Panel review[122] | The panel evaluated established and undifferentiated connective tissue diseases (CTD), and concluded there was no causal evidence between breast implants and these CTDs. |

| 2003 | Spain | Science and Technology Options Assessment (STOA) | The STOA report to the European Parliament Petitions Committee reported that the current scientific evidence demonstrates no solid, causal evidence linking SBI [silicone breast implants] to severe diseases, e.g. breast cancer, connective tissue diseases.[123] |

| 2009 | European Union | International Committee for Quality Assurance, Medical Technologies & Devices in Plastic Surgery panel (IQUAM) | The consensus statement of the Transatlantic Innovations conference (April 2009) indicated that additional medical studies demonstrated no association between silicone gel-filled breast implants and carcinoma, or any metabolic, immune, or allergic disorder.[124] |

See also

- Breast

- Breast augmentation (Augmentation mammoplasty)

- Breast enlargement supplements

- Breast reconstruction

- Breast reduction plasty

- Mammoplasty

- Mastopexy (breast lift)

- Poly Implant Prothèse

- Polypropylene breast implants

- Trans-umbilical breast augmentation (TUBA)

References

- ^ Czerny V (1895). "Plastischer Ersatz der Brusthus durch ein Lipoma". Zentralblatt fur Chirurgie. 27: 72.

- ^ Bondurant S, Ernster V, Herdman R (eds); Committee on the Safety of Silicone Breast Implants (1999). Safety of Silicone Breast Implants. Institute of Medicine. p. 21. ISBN 0-309-06532-1.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Anderson N (1997). "Lawsuit Science: Lessons from the Silicone Breast Implant Controversy". New York Law School Law Review. 41 (2): 401–07.

- ^ Stevens WG, Hirsch EM, Stoker DA, Cohen R. (2006). "In vitro Deflation of Pre-filled Saline Breast Implants". Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 118 (2): 347–349. doi:10.1097/01.prs.0000227674.65284.80. PMID 16874200.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Arion HG (1965). "Retromammary Prosthesis". C R Societé Française de Gynécologie. 5.

- ^ Eisenberg, TS (2009). "Silicone Gel Implants Are Back - So What?". American Journal of Cosmetic Surgery. 26: 5–7.

- ^ Cronin TD, Gerow FJ (1963). "Augmentation Mammaplasty: A New "natural feel" Prosthesis". Excerpta Medica International Congress Series. 66: 41.

- ^ Luu HM, Hutter JC, Bushar HF (1998). "A Physiologically based Pharmacokinetic Model for 2,4-toluenediamine Leached from Polyurethane foam-covered Breast Implants". Environ Health Perspect. 106 (7). Environmental Health Perspectives, Vol. 106, No. 7: 393–400. doi:10.2307/3434066. JSTOR 3434066. PMC 1533137. PMID 9637796.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Hester TR Jr, Tebbetts JB, Maxwell GP (2001). "The Polyurethane-covered Mammary Prosthesis: Facts and Fiction (II): A Look Back and a "peek" Ahead". Clinical Plastic Surgery. 28 (3): 579–86. PMID 11471963.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Brown MH, Shenker R, Silver SA (2005). "Cohesive Silicone Gel Breast Implants in Aesthetic and Reconstructive Breast Surgery". Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 116 (3): 768–779. doi:10.1097/01.prs.0000176259.66948.e7. PMID 16141814.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Fruhstorfer BH, Hodgson EL, Malata CM (2004). "Early Experience with Anatomical Soft Cohesive Silicone gel Prosthesis in Cosmetic and Reconstructive Breast Implant Surgery". Annals of Plastic Surgery. 53 (6): 536–542. doi:10.1097/01.sap.0000134508.43550.6f. PMID 15602249.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Heden P, Jernbeck J, Hober M (2001). "Breast Augmentation with Anatomical Cohesive gel Implants: The World's Largest Current Experience". Clinical Plastic Surgery. 28 (3): 531–52. PMID 11471959.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Brinton L, Brown S, Colton T, Burich M, Lubin J (2000). "Characteristics of a Population of Women with Breast Implants Compared with Women Seeking other Types of Plastic Surgery". Plastic Reconstructive Surgery. 105 (3): 919–927. doi:10.1097/00006534-200003000-00014. PMID 10724251.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Jacobsen PH (2004) Mortality and Suicide Among Danish Women with Cosmetic Breast Implants. Archives of Internal Medicine, 164.

- ^ Young VL; et al. (1994). "The Efficacy of Breast Augmentation: Breast Size Increase, Patient Satisfaction, and Psychological Effects". Plastic Reconstructive Surgery. 94 (Dec): 958–969. doi:10.1097/00006534-199412000-00009. PMID 7972484.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|author-separator=ignored (help) - ^ Crerand CE; et al. (2006). "Body Dysmorphic Disorder and Cosmetic Surgery". Plastic Reconstructive Surgery. 118 (July): 167e–180e. doi:10.1097/01.prs.0000242500.28431.24. PMID 17102719.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|author-separator=ignored (help) - ^ Sarwer DB,; et al. (2003). "Body Image Concerns of Breast Augmentation Patients". Plastic Reconstructive Surgery. 112 (July): 83–90. doi:10.1097/01.PRS.0000066005.07796.51. PMID 12832880.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - ^ Chahraoui K; et al. (2006). "Aesthetic Surgery and Quality of Life Before and Four Months Postoperatively". Journal of the Long-Term Effects of Medical Implants. 51 (3): 207–210. doi:10.1016/j.anplas.2005.07.010. PMID 16181718.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|author-separator=ignored (help) - ^ Cash TF; et al. (2002). "Women's Psychosocial Outcomes of Breast Augmentation with Silicone gel-filled implants: a 2-year Prospective Study". Plastic Reconstructive Surgery. 109 (May): 2112–2121. doi:10.1097/00006534-200205000-00049. PMID 11994621.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|author-separator=ignored (help) - ^ Figueroa-Haas CL (2007). "Effect of Breast Augmentation Mammoplasty on Self-esteem and Sexuality: A Quantitative Analysis". Plastic Surgery Nursing. 27 (Mar): 16–36. doi:10.1097/01.PSN.0000264159.30505.c9. PMID 17356451.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|doi_brokendate=ignored (|doi-broken-date=suggested) (help) - ^ "Important Information for Women About Breast Augmentation with Inamed Silicone Gel-Filled Implants" (PDF). 2006.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ HandelN; et al. (2006). "A Long-term Study of Outcomes, Complications, and Patient Satisfaction with Breast Implants". Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 117 (Mar): 757–767. doi:10.1097/01.prs.0000201457.00772.1d. PMID 16525261.

- ^ "Breast Implants Linked with Suicide in Study". Reuters. 2007-08-08.

- ^ Manning, Anita (2007-08-06). "Breast Implants Linked to Higher Suicide Rates". USA Today. Retrieved 2010-04-26.

- ^ Brinton LA et al. (2001) Mortality Among Augmentation Mammoplasty Patients. Epidemiology, 12.

- ^ Koot VC et al. (2003) Total and Cause-specific Mortality among Swedish Women with Cosmetic Breast Implants: A Prospective Study. British Medical Journal, 326.

- ^ Pukkala E. et al. (2003) Causes of Death among Finnish Women with Cosmetic Breast Implants, 1971–2001. Annals of Plastic Surgery, 51.

- ^ Villeneuve PJ et al. (2006) Mortality Among Canadian Women with Cosmetic Breast Implants. American Journal of Epidemiology, 164.

- ^ Brinton LA et al. (2006) Mortality Rates among Augmentation Mammoplasty Patients: An Update. Epidemiology, 17.

- ^ National Plastic Surgery Procedural Statistics, 2006. Arlington Heights, Illinois, American Society of Plastic Surgeons, 2007

- ^ http://psychcentral.com/news/2007/03/23/plastic-surgery-helps-self-esteem/703.html

- ^ Johnson GW, Christ JE. (1993). "The Endoscopic Breast augmentation: The Transumbilical Insertion of Saline-filled Breast Implants". Plastic Reconstructive Surgery. 92 (5): 801–8. PMID 8415961.

- ^ Wallach SG. (2004). "Maximizing the Use of the Abdominoplasty Incision". Plastic Reconstruction Surgery. 113 (1): 411–417. doi:10.1097/01.PRS.0000091422.11191.1A. PMID 14707667.

- ^ Graf RM; et al. (2003). "Subfascial Breast Implant: A New Procedure". Plastic Reconstructive Surgery. 111 (2): 904–908. doi:10.1097/01.PRS.0000041601.59651.15. PMID 12560720.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|author-separator=ignored (help) - ^ Tebbetts JB (2004). "Does Fascia Provide Additional, Meaningful Coverage over a Breast Implant?". Plastic Reconstructive Surgery. 113 (2): 777–779. doi:10.1097/01.PRS.0000104516.13465.96. PMID 14758271.

- ^ Tebbetts T (2002). "A System for Breast Implant Selection Based on Patient Tissue Characteristics and Implant-soft tissue Dynamics". Plastic Reconstructive Surgery. 109 (4): 1396–1409. doi:10.1097/00006534-200204010-00030. PMID 11964998.

- ^ Pacik, P.T. “Pain Control in Augmentation Mammaplasty: Safety and Efficacy of Indwelling Catheters in 644 Consecutive Patients” Aesthetic Surgery Journal, 28:279–84, May/June 2008

- ^ Pacik, P.T. “Pain Control in Augmentation Mammaplasty Using Indwelling Catheters in 687 Consecutive Patients: Data Analysis”. Aesthetic Surgery Journal, 28:631–41, November/December 2008

- ^ Tebbetts JB A System for Breast Implant Selection Based on Patient Tissue Characteristics and Implant-soft tissue Dynamics. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery Journal. 109(4):1396-1409, April 2002.

- ^ Tebbetts JB and Adams WP. Five Critical Decisions in Breast Augmentation Using 5 measurements in 5 minutes: The High Five System. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery Journal. 116(7), 2005-16, December 2005.

- ^ Tebbetts JB. Achieving a Predictable 24-hour Return to Normal Activities after Breast Augmentation Part I: Refining Practices Using Motion and Time Study Principles. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery Journal. 109:273-290 January 2002.

- ^ Tebbetts JB. Achieving a Predictable 24-hour Return to Normal Activities after Breast Augmentation Part II: Patient Preparation, Refined Surgical Techniques and Instrumentation. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery Journal. 109:293-305, January 2002.

- ^ a b "Important Information for Women About Breast Augmentation with INAMED Silicone-Filled Breast Implants" (PDF). 2006-11-03. Retrieved 2007-05-04.

- ^ "Important Information for Augmentation Patients About Mentor MemoryGel Silicone Gel-Filled Breast Implants" (PDF). 2006-11-03. Retrieved 2007-05-04.

- ^ "Saline-Filled Breast Implant Surgery: Making An Informed Decision (Mentor Corporation)". FDA Breast Implant Consumer Handbook - 2004. 2004-01-13. Retrieved 2007-05-04.

- ^ http://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/ucm260235.htm

- ^ Brown SL, Middleton MS, Berg WA, Soo MS, Pennello G (2000). "Prevalence of Rupture of Silicone gel Breast Implants Revealed on MR Imaging in a Population of Women in Birmingham, Alabama". American Journal of Roentgenology. 175 (4): 1057–1064. PMID 11000165.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Walker PS; et al. (2009). "Natrelle Saline-filled Breast Implants: a Prospective 10-year Study". Aesthetic Surgery Journal. 29 (1): 19–25. doi:10.1016/j.asj.2008.10.001. PMID 19233001.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|author-separator=ignored (help) - ^ Holmich LR; et al. (2004). "Untreated Silicone Breast Implant Rupture". Plastic Reconstructive Surgery. 114 (1): 204–214. doi:10.1097/01.PRS.0000128821.87939.B5. PMID 15220594.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|author-separator=ignored (help) - ^ Katzin; William E; Ceneno; Jose A; Feng; Lu-Jean (2001). "Pathology of Lymph Nodes From Patients With Breast Implants: A Histologic and Spectroscopic Evaluation" (—Scholar search). American Journal of Surgical Pathology. 29 (4): 506–11. PMID 15767806.

{{cite journal}}: External link in|format=|display-authors=6(help); Unknown parameter|author-separator=ignored (help) [dead link] - ^ "Study of Rupture of Silicone Gel-filled Breast Implants (MRI Component)". FDA Breast Implant Consumer Handbook - 2004. 2000-05-22. Retrieved 2007-05-04.

- ^ a b c "Local Complications". FDA Breast Implant Consumer Handbook - 2004. 2004-06-08. Retrieved 2007-05-04.

- ^ MRI of a ruptured silicone breast implant 2013-04-05

- ^ Holmich LR; et al. (2003). "Incidence of Silicone Breast Implant Rupture". Arch Surg. 138 (7): 801–806. doi:10.1001/archsurg.138.7.801. PMID 12860765.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|author-separator=ignored (help) - ^ Heden P; et al. (2006). "Prevalence of Rupture in Inamed Silicone Breast Implants". Plastic Reconstructive Surgery. 118 (2): 303–308. doi:10.1097/01.prs.0000233471.58039.30. PMID 16874191.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|author-separator=ignored (help) - ^ "FDA summary of clinical issues (MS Word document)".

- ^ Cunningham, B; et al. (2009). "Safety and effectiveness of Mentor's MemoryGel implants at 6 years". Plastic Reconstructive Surgery. 33 (3): 440–444. doi:10.1007/s00266-009-9364-6. PMID 19437068.

- ^ Heden P; et al. (2006). "Style 410 Cohesive Silicone Breast Implants: Safety and Effectiveness at 5 to 9 years after Implantation". Plastic Reconstructive Surgery. 118 (6): 1281–1287. doi:10.1097/01.prs.0000239457.17721.5d. PMID 17051096.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|author-separator=ignored (help) - ^ Holmich LR, Fryzek JP, Kjoller K, Breiting VB, Jorgensen A, Krag C, McLaughlin JK (2005). "The Diagnosis of Silicone Breast-implant Rupture: Clinical Findings Compared with Findings at Magnetic Resonance Imaging". Annals of Plastic Surgery. 54 (6): 583–589. doi:10.1097/01.sap.0000164470.76432.4f. PMID 15900139.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b "Expert Advisory Panel on Breast Implants: Record of Proceedings". HealthCanada. 2005-09-29. Retrieved 2007-05-04.

- ^ Song JW, Kim HM, Bellfi LT, Chung KC (2011). "The Effect of Study design Biases on the Diagnostic Accuracy of Magnetic Resonance Imaging for Detecting Silicone Breast Implant Ruptures: a Meta-analysis". Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 127 (3): 1029–1044. doi:10.1097/PRS.0b013e3182043630. PMC 3080104. PMID 21364405.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ independent.co.uk - Breast implants safe, but not for life: US experts

- ^ Barnsley GP; Sigurdson, LJ; Barnsley, SE (2006). "Textured surface Breast Implants in the Prevention of Capsular Contracture among Breast Augmentation Patients: a Meta-analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials". Plastic Reconstructive Surgery. 117 (7): 2182–2190. doi:10.1097/01.prs.0000218184.47372.d5. PMID 16772915.

- ^ Wong CH, Samuel M, Tan BK, Song C. (2006). "Capsular Contracture in Subglandular Breast Augmentation with Textured versus Sooth Breast Implants: a Systematic Review". Plastic Reconstructive Surgery. 118 (5): 1224–1236. doi:10.1097/01.prs.0000237013.50283.d2. PMID 17016195.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Handel N; et al. (2006). "Long-term safety and efficacy of polyurethane foam-covered breast implants". Journal of Aesthetic Surgery. 26 (3): 265–274. doi:10.1016/j.asj.2006.04.001. PMID 19338905.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|author-separator=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) Cite error: The named reference "Handel2006" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). - ^ Mladick RA (1993). ""No-touch" submuscular saline breast augmentation technique". Journal of Aesthetic Surgery. 17 (3): 183–192. doi:10.1007/BF00636260. PMID 8213311.

- ^ Adams WP jr.; Rios, Jose L.; Smith, Sharon J. (2006). "Enhancing Patient Outcomes in Aesthetic and Reconstructive Breast Surgery using Triple Antibiotic Breast Irrigation: Six-year Prospective Clinical Study". Plastic Reconstructive Surgery. 117 (1): 30–6. doi:10.1097/01.prs.0000185671.51993.7e. PMID 16404244.

- ^ Planas J; Cervelli, V; Planas, G (2001). "Five-year experience on ultrasonic treatment of breast contractures". Aesthetic Plastic Surgery. 25 (2): 89–93. doi:10.1007/s002660010102. PMID 11349308.

- ^ Schlesinger SL, wt al (2002). "Zafirlukast (Accolate): A new treatment for capsular contracture". Aesthetic Plast Surg. 22 (4): 329–36.

- ^ Scuderi N; et al. (2006). "The effects of zafirlukast on capsular contracture: preliminary report". Aesthetic Plast Surg. 30 (5): 513–520. doi:10.1007/s00266-006-0038-3. PMID 16977359.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|author-separator=ignored (help) - ^ Silver H (1982). "Reduction of capsular contracture with two-stage augmentation mammaplasty and pulsed electromagnetic energy (Diapulse therapy)". Plastic Reconstructive Surgery. 69 (5): 802–805. doi:10.1097/00006534-198205000-00013. PMID 7071225.

- ^ Tebbets JB (2006). "Out Points Criteria for Breast Implant Removal without Replacement and Criteria to Minimize Reoperations following Breast Augmentation". Plastic Reconstructive Surgery. 114 (5): 1258–1262. PMID 15457046.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Tebbets JB (2006). "Achieving a Zero Percent Reoperation Rate at 3 years in a 50-consecutive-case Augmentation Mammaplasty Premarket Approval Study". Plastic Reconstructive Surgery. 118 (6): 1453–7. doi:10.1097/01.prs.0000239602.99867.07. PMID 17051118.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Therapeutic Goods Administration (2001). Breast Implant Information Booklet (PDF) (4th ed.). Australian Government. ISBN 0-642-73579-4.

- ^ European Committee on Quality Assurance and Medical Devices in Plastic Surgery (2000-06-23). "Consensus Declaration on Breast Implants" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on December 30, 2006. Retrieved 2007-05-04.

- ^ "Silicone Gel Breast Implant Report Launched - No Epidemiological Evidence For Link With Connective Tissue Disease - Independent Review Group". 1998-07-13. Retrieved 2007-05-04.

- ^ a b Breiting VB, Holmich LR, Brandt B, Fryzek JP, Wolthers MS, Kjoller K, McLaughlin JK, Wiik A, Friis S (2004). "Long-term Health Status of Danish Women with Silicone Breast Implants". Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 114 (1): 217–226. doi:10.1097/01.PRS.0000128823.77637.8A. PMID 15220596.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Kjoller K, Holmich LR, Fryzek JP, Jacobsen PH, Friis S, McLaughlin JK, Lipworth L, Henriksen TF, Hoier-Madsen M, Wiik A, Olsen JH (2004). "Self-reported musculoskeletal symptoms among Danish women with cosmetic breast implants". Annals of Plastic Surgery. 52 (1): 1–7. doi:10.1097/01.sap.0000101930.75241.55. PMID 14676691.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Fryzek JP, Holmich L, McLaughlin JK, Lipworth L, Tarone RE, Henriksen T, Kjoller K, Friis S (2007). "A Nationwide Study of Connective Tissue Disease and Other Rheumatic Conditions Among Danish Women With Long-Term Cosmetic Breast Implantation". Annals of Epidemiology. 17 (5): 374–379. doi:10.1016/j.annepidem.2006.11.001. PMID 17321754.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Brinton LA, Lubin JH, Murray MC, Colton T, Hoover RN (2006). "Mortality Rates Among Augmentation Mammoplasty patients: an update". Epidemiology. 17 (2): 162–9. doi:10.1097/01.ede.0000197056.84629.19. PMID 16477256.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ McLaughlin JK, Lipworth L, Fryzek JP, Ye W, Tarone RE, Nyren O (2006). "Long-term Cancer Risk Among Swedish Women with Cosmetic Breast Implants: an Update of a Nationwide Study". J Natl Cancer Inst. 98 (8): 557–60. doi:10.1093/jnci/djj134. PMID 16622125.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Villenueve PJ; et al. (2006). "Mortality among Canadian Women with Cosmetic Breast Implants". American Journal of Epidemiology. 164 (4): 334–341. doi:10.1093/aje/kwj214. PMID 16777929.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|author-separator=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) Cite error: The named reference "Villenueve2006" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). - ^ Brown SL, Pennello G, Berg WA, Soo MS, Middleton MS (2001). "Silicone gel Breast Implant Rupture, Extracapsular Silicone, and Health Status in a Population of Women". Journal of Rheumatology. 28 (5): 996–1003. PMID 11361228.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Lipworth L, Tarone RE, McLaughlin JK. (2004). "Breast Implants and Fibromyalgia: a Review of the Epidemiologic Evidence". Annals of Plastic Surgery. 52 (3): 284–287. doi:10.1097/01.sap.0000116024.18713.28. PMID 15156983.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Diseases". FDA Breast Implant Consumer Handbook - 2004. 2004-06-08. Retrieved 2007-05-04.

- ^ Lipworth L, Holmich LR, McLaughlin JK. (2011). "Silicone breast implants and connective tissue disease: no association". Semin Immunopathol. 33 (3): 287–294. doi:10.1007/s00281-010-0238-4. PMID 21369953.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Rinzler, Carol Ann (2009) The encyclopedia of Cosmetic and Plastic Surgery New York:Facts on File, p.23.

- ^ Arepelli S; et al. (2002). "Allergic reactions to platinum in silicone breast implants". J Long-Term Effects Medical Implants. 12 (4): 299–306. PMID 12627791.