Robot Jox: Difference between revisions

Removing external link |

|||

| Line 29: | Line 29: | ||

==Plot== |

==Plot== |

||

Fifty years after a nuclear holocaust, open war is forbidden by the surviving nations, which have merged into two opposing factions: the western-influenced Market and the Russian-themed Confederation. To resolve territorial disputes, the two sides hold gladiator-style matches between [[Mecha|giant robots]] piloted by "robot jox". In a contest between Confederation fighter Alexander ([[Paul Koslo]]) and the Market's Hercules, it becomes clear that the Confederation is receiving information about new weaponry and designs from spies within the Market, resulting in the loss of critical matches and the deaths of several of the Market's best pilots. Market jock Achilles ([[Gary Graham]]), supported by robot designer "Doc" Matsumoto ([[Danny Kamekona]]) and strategist Tex Conway ([[Michael Alldredge]]), the only jock to win all ten of his contract fights, prepares for his final contracted fight with Alexander. During the battle, Achilles attempts to intercept a wayward projectile launched by Alexander when it careens towards a civilian spectator section, but his robot takes the full impact and collapses on top of the bleachers, killing over 300 spectators. In a post-match conference, both sides reason that their respective fighter was the victor; however, the referees decide that the match is inconclusive and schedule a rematch. Achilles, shaken by the incident, insists the fight was his contractual tenth match and retires, much to the disapproval of his management and fans. |

Fifty years after a nuclear holocaust, open war is forbidden by the surviving nations, which have merged into two opposing factions: the western-influenced Market and the Russian-themed Confederation. To resolve territorial disputes, the two sides hold gladiator-style matches between [[Mecha|giant robots]] piloted by "robot [[jockey|jox]]". In a contest between Confederation fighter Alexander ([[Paul Koslo]]) and the Market's Hercules, it becomes clear that the Confederation is receiving information about new weaponry and designs from spies within the Market, resulting in the loss of critical matches and the deaths of several of the Market's best pilots. Market jock Achilles ([[Gary Graham]]), supported by robot designer "Doc" Matsumoto ([[Danny Kamekona]]) and strategist Tex Conway ([[Michael Alldredge]]), the only jock to win all ten of his contract fights, prepares for his final contracted fight with Alexander. During the battle, Achilles attempts to intercept a wayward projectile launched by Alexander when it careens towards a civilian spectator section, but his robot takes the full impact and collapses on top of the bleachers, killing over 300 spectators. In a post-match conference, both sides reason that their respective fighter was the victor; however, the referees decide that the match is inconclusive and schedule a rematch. Achilles, shaken by the incident, insists the fight was his contractual tenth match and retires, much to the disapproval of his management and fans. |

||

[[File:Robot Jox screenshot.jpg|thumb|left|The "crash and burn" gesture of peace from the film's conclusion|alt=Two hands covered in technological gadgetry entering the frame from both sides make a "thumbs up" gesture while performing a fist bump.]] |

[[File:Robot Jox screenshot.jpg|thumb|left|The "crash and burn" gesture of peace from the film's conclusion|alt=Two hands covered in technological gadgetry entering the frame from both sides make a "thumbs up" gesture while performing a fist bump.]] |

||

Revision as of 18:30, 2 January 2014

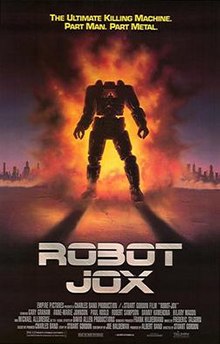

| Robot Jox | |

|---|---|

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Stuart Gordon |

| Screenplay by | Joe Haldeman |

| Story by | Stuart Gordon |

| Produced by | Charles Band |

| Starring | Gary Graham Anne-Marie Johnson Paul Koslo |

| Cinematography | Mac Ahlberg |

| Edited by | Lori Ball Ted Nicolaou |

| Music by | Frédéric Talgorn |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Trans World Entertainment (Theatrical) Columbia Pictures (Canada) MGM/UA Home Entertainment (Home media) |

Release date |

|

Running time | 85 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $10 million[1][Note 1] |

| Box office | $1,272,977[3] |

Robot Jox is a 1990 post-apocalyptic science fiction film directed by Stuart Gordon and starring Gary Graham, Anne-Marie Johnson, and Paul Koslo. The film was co-written by science fiction author Joe Haldeman.

The film's plot follows Achilles, one of the "robot jox" who pilot giant mechanical machines that fight international battles to settle territorial disputes in a dystopian post-apocalyptic world. Achilles retires after his final contracted battle against his primary rival, Alexander, ends in an inconclusive disaster, but returns when he realizes that a female genetically engineered athlete, Athena, will replace him. Athena attempts to steal the robot and fight against Alexander anyway, and when she is defeated, Achilles reclaims his robot to fight. After a prolonged battle, Achilles and Alexander reconcile and salute each other.

After producer Charles Band approved Gordon's initial concept, the director approached Haldeman to write the script. Gordon and Haldeman clashed frequently over the film's tone and intended audience. Principal photography finished in Rome in 1987, but the bankruptcy of Band's Empire Pictures delayed the film's release in theaters until 1990. It earned $1,272,977 in domestic gross, failing to earn its production cost in theaters. The film received negative critical response and little audience attention upon its first theatrical run, but has attracted a minor cult following and influenced elements of popular culture since its initial release.

Plot

Fifty years after a nuclear holocaust, open war is forbidden by the surviving nations, which have merged into two opposing factions: the western-influenced Market and the Russian-themed Confederation. To resolve territorial disputes, the two sides hold gladiator-style matches between giant robots piloted by "robot jox". In a contest between Confederation fighter Alexander (Paul Koslo) and the Market's Hercules, it becomes clear that the Confederation is receiving information about new weaponry and designs from spies within the Market, resulting in the loss of critical matches and the deaths of several of the Market's best pilots. Market jock Achilles (Gary Graham), supported by robot designer "Doc" Matsumoto (Danny Kamekona) and strategist Tex Conway (Michael Alldredge), the only jock to win all ten of his contract fights, prepares for his final contracted fight with Alexander. During the battle, Achilles attempts to intercept a wayward projectile launched by Alexander when it careens towards a civilian spectator section, but his robot takes the full impact and collapses on top of the bleachers, killing over 300 spectators. In a post-match conference, both sides reason that their respective fighter was the victor; however, the referees decide that the match is inconclusive and schedule a rematch. Achilles, shaken by the incident, insists the fight was his contractual tenth match and retires, much to the disapproval of his management and fans.

After competing for the position with other genetically engineered "gen jox", Athena (Anne-Marie Johnson) is chosen to replace Achilles. Concerned that she may not win, Achilles agrees to fight Alexander again, which infuriates Athena. Prior to the scheduled rematch, Doc confronts Conway in his office. He analyzes Conway's final match and deduces that the "lucky" laser hit that won Conway the match against a clearly superior opponent was in fact deliberately aimed and the match was rigged for Conway to win. He accuses Conway of being a spy who has leaked Market robot information to the Confederation. Conway confesses and murders Doc, unaware that Doc has recorded the conversation. Conway tells Commissioner Jameson (Robert Sampson) that Doc was the spy, and that he committed suicide upon being outed.

On the morning of the fight, Athena sedates Achilles in his apartment and impersonates him to gain access to the robot's cockpit, forcefully taking his robot to the field. Achilles decides to help her and plays the instructional video Doc had prepared for the new weapons installed in the robot. When the video cuts to footage of Conway's confession and Doc's murder, Conway leaps to his death. On the field, Alexander overpowers Athena and Achilles rushes to get her out of the robot. The referees order Alexander to stop fighting or be disqualified, but Alexander destroys the referees' float platform and continues the attack. Achilles takes control of the Market robot and ignores Commissioner Jameson's instruction to stop the match due to Alexander's disqualification. The two jox continue their fight, with both robots eventually being crippled and destroyed. Facing each other without their machines and using wreckage as weapons, they fight in hand-to-hand combat. Achilles convinces Alexander that a match does not necessarily have to end with the death of a jock. Alexander throws down his weapon, and they salute each other with the jox's traditional "crash and burn" fist bump.[Note 2]

Cast

- Gary Graham – Achilles/Jim

- Anne-Marie Johnson – Athena

- Paul Koslo – Alexander

- Robert Sampson – Commissioner Jameson (sic)

- Danny Kamekona – Dr. "Doc" Matsumoto

- Hilary Mason – Professor Laplace

- Michael Alldredge – Tex Conway

- Jeffrey Combs – Spectator/Prole #1

- Michael Saad – Spectator/Prole #2

- Ian Patrick Williams – Phillip

- Jason Marsden – Tommy

- Carolyn Purdy-Gordon – Kate

- Thyme Lewis – Sargon

- Gary Houston – Sportscaster

- Russel Case – Hercules

- Stuart Gordon (uncredited) – Bartender

Production

Director Stuart Gordon stated that the initial inspiration for Robot Jox came from the Japanese Transformers toy line:

While there have been animated cartoons based on these giant robots, no one has ever attempted a live-action feature about them. It struck me that it was a natural fantasy for the big screen–and a terrific opportunity to take advantage of the special effects that are available today.[2]

When Gordon initially approached producer Charles Band with the concept, Band said the film would be too expensive for his studio, Empire Pictures, to produce. Band changed his mind, however, and asked Gordon to create a demo reel of stop motion test footage with special effects artist David W. Allen. The footage impressed the film's potential backers, and eventually became the film's opening title sequence.[2] Initially budgeted at $7 million, the film was to be the most expensive film Empire Pictures had ever produced.[5]

Science-fiction author Joe Haldeman wrote the screenplay for the film and co-wrote the story with Gordon. The two met when Gordon was hired to film a four-part adaptation of Haldeman's novel The Forever War, but when funding for the project was cut, Gordon instead directed a stage adaptation of the book, which Haldeman also wrote. Two years later, Gordon asked Haldeman to work on a science fiction adaptation of the Iliad; the idea would form the basis for what eventually became Robot Jox.[6] Haldeman claimed his and Gordon's visions for the film clashed: The former wanted a dramatic, serious science fiction film while the latter wanted a more audience-friendly, special effects-driven action film with stereotypical characters and stylized pseudo-science. In a 1+1⁄2-page outline, Gordon inserted other elements into the plot, including the film's Cold War-era themes. Haldeman wanted to title the film The Mechanics, but Gordon insisted on Robojox.[Note 3] According to Haldeman:

I would try to change the science into something reasonable; Stuart would change it back to Saturday morning cartoon stuff. I tried to make believable, reasonable characters, and Stuart would insist on throwing in clichés and caricatures. It was especially annoying because it was a story about soldiers, and I was the only person around who'd ever been one.[7]

Several times, Haldeman feared that this clash would lead to him being dropped from the project, but the film's producers sided with him during pre-production. Haldeman wrote that Gordon later recognized that the author was "writing a movie for adults that children can enjoy" while Gordon had been "directing a movie for children that adults can enjoy."[7]

Principal photography on the film began in Rome in January 1987 and ended in April. During filming, the producers brought in Haldeman to work with the film's principal actors.[7] Afterwards, Allen began to produce the film's special effects sequences along with Ron Cobb to help design the robots. Allen chose to film these sequences at El Mirage lake bed in San Bernardino County, California due to its bright skies and unobstructed panoramic view; however, weather elements frequently delayed filming. According to Gordon:

Everything that could have gone wrong went wrong. There were sandstorms, flooding, and sets getting destroyed by winds. He wanted to shoot it outside. Normally, you shoot miniature work in a very controlled environment, but Dave had this idea that he wanted to shoot it against real skies, and real mountains, and really give this thing a sense of reality. Because of the sunlight, the depth of field was such that you could fool the eye.[8]

Release

Although originally scheduled for release in 1989 (a novelization, written by science fiction author Robert Thurston, was published that year)[9] the film's theatrical run was initially delayed until April 1990 due to Empire International Pictures' bankruptcy during production.[10] After more delays, Triumph Films released the film to theaters on November 21, 1990. When it peaked in its second weekend at the 13th spot, it grossed $464,441 in 333 theaters, averaging $1,394 per theater; it eventually earned a domestic total gross of $1,272,977.[3] Its limited run in theaters prompted science fiction writer Gardner Dozois to remark that "Robot Jox, a movie with a screenplay by Joe Haldeman, was supposedly released this year, but if it played through Philadelphia at all, it must have done so fast, because I never even saw a listing for it, let alone the movie itself."[11]

Soundtrack

| Untitled | |

|---|---|

Frédéric Talgorn, who had previously composed the music the 1989 horror film Edge of Sanity, wrote the orchestral film score for Robot Jox, which was performed by the Paris Philharmonic Orchestra. Since Prometheus Records reissued the soundtrack in 1993, it has received generally high acclaim. An editorial review by Filmtracks.com stated that "Talgorn's usual strong development of thematic ideas is well utilized in rather simplistic fashion in this film, perfect for the contrasting characters and their underdeveloped dimensions."[12] In 2004, AllMusic critic Jason Ankeny wrote that "with its dynamic brass fanfares, martial rhythms and bold themes, Robot Jox is a profoundly heroic work buoyed by larger-than-life orchestral rendering."[13]

Home media

Sony Pictures Home Entertainment released the film on VHS and Laserdisc formats.[Note 4] In October 2005, MGM Home Entertainment released the film on DVD. Though the cover still includes the film's theatrical PG rating, the version of the film included contains violent scenes that were cut from the North American release to avoid the PG–13 rating.[14]

Reception

Robot Jox received little media coverage during its initial release, but the professional critics who did review it rated it poorly, noting the film's struggle to find a balance between adult and child audiences. By that time the film was released, its Cold War themes had become less relevant to United States audiences and the popularity of Transformers, which the filmmakers had intended to capitalize on, had diminished.[15][1] The Sacramento Bee wrote that the film "spreads its dubious resources across the world, dealing with the already dated power-mad rivalry between America and the U.S.S.R. for domination."[16] Haldeman was generally unsatisfied with the movie, later writing that "it's as if I'd had a child who started out well and then sustained brain damage."[7] Academic criticism was somewhat more positive, with film scholar J. P. Telotte writing:

While a recent film like Robot Jox (1990) ... revels in exploring the technical complexities of its central conceit–nations warring vicariously through giant robots piloted by gladiator-type "jockies"–it repeatedly emphasizes how much of the human has been surrendered to the technological and concludes with its chief antagonists abandoning their mechanical mounts to live in peace. Robot Jox, though, is just one of a great many such films to depict the attractions and promises of science and technology as essentially fictions, dangerous illusions from which we eventually have to pull back as best we can if we are to retain our humanity.[17]

Later response

Since its initial release, Robot Jox has attracted a minor following of devoted fans and influenced various elements of popular culture. In 1994, industrial rock band Nine Inch Nails sampled and looped a sound effect in the film for the song "The Becoming" from their album The Downward Spiral.[18] Concept artist Robert Simons featured a series of detailed works in 2010 based on designs from the film.[19] In February 2012, Cinema Studies Student Union showed the film at Innis College, Toronto as part of a "cult film triple bill",[20] and in August, the Alamo Drafthouse Cinema locations in Houston and Austin held special midnight screenings of a 35 mm copy of the film.[6] In January 2013, the website CHUD.com featured the film as its movie of the day, with reviewer Michael Monterastelli remarking that the film is "part serious science fiction, part Saturday morning cartoon and it’s one hell of a good time."[21]

Critical reception to the film has also improved. In 2009, Isthmus film critic Mark Savlov wrote that the computer-generated imagery in Terminator Salvation "still can't hold a candle to the stop-motion and very endearing goofiness of Stuart Gordon's 1990 Robot Jox."[22] Critic Alex Fitch praised Gordon's work in 2010, citing Robot Jox as an example of how Gordon "can mix satire with special effects to great aplomb."[1] Writing for The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction in 2012, Kim Newman noted that Gordon's style gave the film "a pleasantly uncluttered comic-bookish look", while Haldeman's influences could be seen "in his distinctive blend of military-hardware expertise and anti-war attitudes".[9]

After the trailer for Guillermo del Toro's film Pacific Rim was released in December 2012, online critics and bloggers began to revisit the film, noting the similarities between the two films.[23][24] Bloomberg Businessweek writer Clarie Suddath noted that Pacific Rim was "a mash-up of the 1980s B-movie film Robojox [sic] and Godzilla on steroids".[25] In May 2013, RedLetterMedia featured the film on an episode of their online "Best of the Worst" series, joking that it was a "screener of Guillermo del Toro's new movie". Jay Bauman called the film "a genuinely enjoyable B-movie".[26]

Notes

- ^ Although most official reports place the budget for the film at $10 million, director Stuart Gordon has stated that "the actual budget ended up being about $6.5 million."[2]

- ^ In 2012, Haldeman wrote that he had first heard the phrase "crash and burn" used as a greeting between motorcycle racers during a Speedweek event.[4]

- ^ After Orion Pictures threatened to sue based on the title's similarity to their 1987 film Robocop, producers changed the title to Robot Jox.[2]

- ^ The direct-to-video films Crash and Burn and Robot Wars were marketed on home video in some countries as sequels to Robot Jox, but despite some similarities and the involvement of producer Charles Band, the plots of the three films are unrelated.[6]

References

- ^ a b c Fitch, Alex (2010). "Directors: Stuart Gordon". In Berra, John (ed.). Directory of World Cinema. Vol. 2. Bristol: Intellect Books. pp. 33–35. ISBN 9781841503684. OCLC 762158992. Retrieved 2012-06-14.

- ^ a b c d Counts, Kyle (1989). Schoengood, Bruce (ed.). "Robot Jox Rides Again". Horrorfan. 1 (2): 54–58.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b Robot Jox at Box Office Mojo

- ^ Haldeman, Joe (2012-01-16). "Slogans". Archived from the original on 2012-02-07. Retrieved 2013-02-17.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Gordon, Stuart (1986). "Stuart Gordon". "Film Directors on Directing" (Interview). Interviewed by John A. Gallagher. pp. 90–99. Retrieved 2013-02-14.

Robojox is seven million, the biggest budget Empire's ever had.

{{cite interview}}: External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|city=ignored (|location=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|subjectlink=ignored (|subject-link=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c Saucedo, Robert (2012-07-30). "Crash And Burn. See Robot Jox On The Big Screen At The Alamo Drafthouse". BadassDigest.com. Retrieved 2012-10-25.

- ^ a b c d Haldeman, Joe. "Interim Report – An Autobiographical Ramble". Archived from the original on 2011-05-14. Retrieved 2012-06-14.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Gordon, Stuart (2005-03-23). "Cinema CPR: The Films of Stuart Gordon" (Interview). Interviewed by KJ Doughton. Retrieved 2013-02-17.

{{cite interview}}: Unknown parameter|subjectlink=ignored (|subject-link=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Newman, Kim (2012-09-30). "Media: Robot Jox". The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. Archived from the original on 2013-04-30. Retrieved 2013-06-05.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Bamford, Paul (2002). "Stuart Gordon". In Allon, Yoram; Cullen, Del; Patterson, Hannah (eds.). Contemporary North American Film Directors: A Wallflower Critical Guide (2nd ed.). London: Wallflower Press. pp. 206–207. ISBN 9781903364529. OCLC 51480273. Retrieved 2012-06-14.

- ^ Dozois, Gardner (1991-06-15). "Summation: 1990". The Year's Best Science Fiction: Eighth Annual Collection. Macmillan. ISBN 9781466829473. Retrieved 2013-02-14.

- ^ Clemmensen, Christian (1997-04-19). "Robot Jox – Editorial Review". Archived from the original on 2010-01-14. Retrieved 2012-10-25.

- ^ Ankeny, Jason (2004-02-14). "Original Soundtrack – Robot Jox". Allmusic.com. Retrieved 2012-10-25.

- ^ Erickson, Glenn; Charles, John (2005-11-28). "DVD Savant Review – Robot Jox". DVDTalk.com. Archived from the original on 2010-01-08. Retrieved 2013-01-03.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Murray, Steve (1990-12-18). "'Robot' Runs Out of Steam Going Through the Motions". The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. p. E8. Retrieved 2013-02-17 – via NewsBank (subscription required) .

As a pre-glasnost pep talk, Robot Jox is all right.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "No Brains, or Heart in Robot Jox". The Sacramento Bee. 1990-12-24. p. SC3. Retrieved 2012-10-25 – via NewsBank (subscription required) .

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Telotte, J. P. (1995). Replications: A Robotic History of the Science Fiction Film. Urbana, Illinois: University of Illinois Press. p. 8. ISBN 9780252064661. OCLC 32133305.

- ^ Kushner, Nick. "Films, Samples and Influences". The Nachtkabarett. Retrieved 2012-10-18.

- ^ Anders, Charlie Jane. "Giant Robots Pounding Each Other Have Never Looked So Majestic". Io9.com. Retrieved 2012-10-25.

- ^ Peter K. (2012-02-22). "Toronto Screenings: Nowhere to Hide! Robot Jox! Lady Terminator! ALL FREE!". TwitchFilm.com. Retrieved 2013-01-03.

- ^ Monterastelli, Michael (2013-01-17). "Movie of the Day: Robot Jox". Archived from the original on 2013-01-21.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Savlov, Mark (2009-05-22). "Terminator Salvation: No Fun, No Soul". Isthmus. Madison, Wisconsin. Retrieved 2012-10-25.

- ^ Mike (?) and Bo Ransdell (2012-12-21). "EP17 – From Beyond". horrorphilia.com (Podcast). Badasses, Boobs, and Body Counts. Event occurs at 12:20. Retrieved 2012-12-22.

- ^ "Film Preview: Pacific Rim (2013)". SciFiMethods.com. 2012-12-04. Retrieved 2013-01-03.

Amongst other films and media, Robot Jox (1989) is recognizable in the trailer as a clear influence.

- ^ Suddath, Claire (2013-07-13). "With Pacific Rim, Moviegoers Show Signs of Apocalypse Fatigue". businessweek.com. Bloomberg Businessweek. Retrieved 2013-07-15.

- ^ Bauman, Jay (2013). Best of the Worst: The Vindicator, Cyber Tracker, Robot Jox, and R.O.T.O.R. (Online video). Milwaukee: RedLetterMedia. Event occurs at 4:15. Retrieved 2013-07-04.

External links

- Robot Jox at IMDb

- Robot Jox at Box Office Mojo

- Robot Jox at Rotten Tomatoes

- The Making of Robot Jox – Includes special effects production stills

- 1990 films

- 1990s action films

- 1990s science fiction films

- American science fiction action films

- English-language films

- Dystopian films

- Fictional games

- Films shot in California

- Films shot in Rome

- Independent films

- Post-apocalyptic films

- Robot films

- Stop-motion animated films

- Empire International Pictures films

- Columbia Pictures films