Garden of Eden: Difference between revisions

this previous wording was more neutral |

|||

| Line 52: | Line 52: | ||

In the [[Talmud]] and the Jewish [[Kabbalah]],<ref name="Gan Eden">[http://www.jewishencyclopedia.com/view.jsp?artid=39&letter=E Gan Eden] – JewishEncyclopedia; 02-22-2010.</ref> the scholars agree that there are two types of spiritual places called "Garden in Eden". The first is rather terrestrial, of abundant fertility and luxuriant vegetation, known as the "lower Gan Eden". The second is envisioned as being celestial, the habitation of righteous, Jewish and non-Jewish, immortal souls, known as the "higher Gan Eden". The [[Rabbi|Rabbanim]] differentiate between ''Gan'' and Eden. Adam is said to have dwelt only in the ''Gan'', whereas Eden is said never to be witnessed by any mortal eye.<ref name="Gan Eden"/> |

In the [[Talmud]] and the Jewish [[Kabbalah]],<ref name="Gan Eden">[http://www.jewishencyclopedia.com/view.jsp?artid=39&letter=E Gan Eden] – JewishEncyclopedia; 02-22-2010.</ref> the scholars agree that there are two types of spiritual places called "Garden in Eden". The first is rather terrestrial, of abundant fertility and luxuriant vegetation, known as the "lower Gan Eden". The second is envisioned as being celestial, the habitation of righteous, Jewish and non-Jewish, immortal souls, known as the "higher Gan Eden". The [[Rabbi|Rabbanim]] differentiate between ''Gan'' and Eden. Adam is said to have dwelt only in the ''Gan'', whereas Eden is said never to be witnessed by any mortal eye.<ref name="Gan Eden"/> |

||

According to [[Jewish eschatology]],<ref>[http://www.jewfaq.org/olamhaba.htm Olam Ha-Ba – The Afterlife] - JewFAQ.org; 02-22-2010.</ref><ref name="Eshatology">[http://www.jewishencyclopedia.com/view.jsp?artid=460&letter=E#1239 Eshatology] – JewishEncyclopedia; 02-22-2010.</ref> the higher Gan Eden is called the "Garden of Righteousness". It has been created since the beginning of the world, and will appear gloriously at the end of time. The righteous dwelling there will enjoy the sight of the heavenly ''[[chayot]]'' carrying the throne of God. Each of the righteous will walk with God, who will lead them in a dance. Its Jewish and non-Jewish inhabitants are "clothed with garments of light and eternal life, and eat of the tree of life" (Enoch 58,3) near to God and His anointed ones.<ref name="Eshatology"/> This Jewish rabbinical concept of a higher Gan Eden is opposed by the Hebrew terms ''[[gehinnom]]''<ref>"Gehinnom is the Hebrew name; Gehenna is Yiddish." [http://www.jewfaq.org/cgi-bin/search.cgi?Keywords=Gehinnom Gehinnom – Judaism 101] websourced 02-10-2010.</ref> and ''[[sheol]]'', figurative names for the place of spiritual purification for the wicked dead in Judaism, a place envisioned as being at the greatest possible distance from [[heaven]].<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.jewfaq.org/olamhaba.htm#Gan |title=Gan Eden and Gehinnom |publisher=Jewfaq.org |accessdate=2011-06-30}}</ref> |

According to [[Jewish eschatology]],<ref>[http://www.jewfaq.org/olamhaba.htm Olam Ha-Ba – The Afterlife] - JewFAQ.org; 02-22-2010.</ref><ref name="Eshatology">[http://www.jewishencyclopedia.com/view.jsp?artid=460&letter=E#1239 Eshatology] – JewishEncyclopedia; 02-22-2010.</ref> the higher Gan Eden is called the "Garden of Righteousness". It has been created since the beginning of the world, and will appear gloriously at the end of time. The righteous dwelling there will enjoy the sight of the heavenly ''[[chayot]]'' carrying the throne of God. Each of the righteous will walk with God, who will lead them in a dance. Its Jewish and non-Jewish inhabitants are "clothed with garments of light and eternal life, and eat of the tree of life" (Enoch 58,3 - This citation is wrong.) near to God and His anointed ones.<ref name="Eshatology"/> This Jewish rabbinical concept of a higher Gan Eden is opposed by the Hebrew terms ''[[gehinnom]]''<ref>"Gehinnom is the Hebrew name; Gehenna is Yiddish." [http://www.jewfaq.org/cgi-bin/search.cgi?Keywords=Gehinnom Gehinnom – Judaism 101] websourced 02-10-2010.</ref> and ''[[sheol]]'', figurative names for the place of spiritual purification for the wicked dead in Judaism, a place envisioned as being at the greatest possible distance from [[heaven]].<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.jewfaq.org/olamhaba.htm#Gan |title=Gan Eden and Gehinnom |publisher=Jewfaq.org |accessdate=2011-06-30}}</ref> |

||

In modern [[Jewish eschatology]], it is believed that history will complete itself and the ultimate destination will be when all mankind returns to the Garden of Eden.<ref>{{cite web|title=End of Days|url=http://www.aish.com/ci/a/48925077.html|work=End of Days|publisher=Aish|accessdate=1 May 2012}}</ref> |

In modern [[Jewish eschatology]], it is believed that history will complete itself and the ultimate destination will be when all mankind returns to the Garden of Eden.<ref>{{cite web|title=End of Days|url=http://www.aish.com/ci/a/48925077.html|work=End of Days|publisher=Aish|accessdate=1 May 2012}}</ref> |

||

Revision as of 07:14, 25 November 2014

The Garden of Eden (Hebrew גַּן עֵדֶן, Gan ʿEdhen) is the biblical "garden of God", described most notably in the Book of Genesis chapters 2 and 3, and also in the Book of Ezekiel.[2] The "garden of God", not called Eden, is mentioned in Genesis 14, and the "trees of the garden" are mentioned in Ezekiel 31. The Book of Zechariah and the Book of Psalms also refer to trees and water in relation to the temple without explicitly mentioning Eden.[3]

Traditionally, the favoured derivation of the name "Eden" was from the Akkadian edinnu, derived from a Sumerian word meaning "plain" or "steppe". Eden is now believed to be more closely related to an Aramaic root word meaning "fruitful, well-watered."[2] The Hebrew term is translated "pleasure" in Sarah's secret saying in Genesis 18:12.[4]

The story of Eden echoes the Mesopotamian myth of a king, as a primordial man, who is placed in a divine garden to guard the tree of life.[5] In the Hebrew Bible, Adam and Eve are depicted as walking around the Garden of Eden naked due to their innocence.[6] Eden and its rivers may signify the real Jerusalem, the Temple of Solomon, or the Promised Land. It may also represent the divine garden on Zion, and the mountain of God, which was also Jerusalem. The imagery of the Garden, with its serpent and cherubs, has been compared to the images of the Solomonic Temple with its copper serpent, the nehushtan, and guardian cherubs.[7]

Biblical narratives

Eden in Genesis

The second part of the Genesis creation narrative, in 2:4–3:24 Gen.2:4–3:24 9Template:Bibleverse with invalid book, opens with "the LORD God"(v.7) creating the first man (Adam), whom he placed in a garden that he planted "eastward in Eden".(v.8)

And out of the ground made the LORD God to grow every tree that is pleasant to the sight, and good for food; the tree of life also in the midst of the garden, and the tree of knowledge of good and evil. —Genesis 2:9

The man was free to eat off of any tree in the garden, but forbidden to eat from the tree of knowledge of good and evil. Last of all, the LORD God made a woman (Eve) from a rib of the man to be a companion to the man. In chapter 3, the man broke the commandment and ate of the forbidden fruit, and was sent forth from the garden to prevent him from eating also of the tree of life, and thus live for ever. East of the garden there were placed Cherubims, "and a flaming sword which turned every way, to keep the way of the tree of life". (Gen.3:24)

2:10–14 Gen.2:10–14 9Template:Bibleverse with invalid book lists four rivers in association with the garden of Eden: Pishon, Gihon, the Hiddekel, and the Euphrates. It also refers to the land of Cush - translated/interpreted as Ethiopia, but thought by some to equate to Cossaea, a Greek name for the land of the Kassites.[8] These lands lie north of Elam, immediately to the east of ancient Babylon, which, unlike Ethiopia, does lie within the region being described.[9] In Antiquities of the Jews, the first-century Jewish historian Josephus identifies the Pishon as what "the Greeks called Ganges" and the Geon (Gehon) as the Nile.[10]

Eden in Ezekiel

In Ezekiel 28:12–19 (NIV) the prophet Ezekiel the "son of man" sets down God's word against the king of Tyre: the king was the "seal of perfection", adorned with precious stones from the day of his creation, placed by God in the garden of Eden on the holy mountain as a guardian cherub. But the king sinned through wickedness and violence, and so he was driven out of the garden and thrown to the earth, where now he is consumed by God's fire: "All the nations who knew you are appalled at you, you have come to a horrible end and will be no more." (v.19)

The Eden in Ezekiel appears to be located in Lebanon.[11] "[I]t appears that the Lebanon is an alternative placement in Phoenician myth (as in Ez 28,13, III.48) of the Garden of Eden",[12] and there are connections between paradise, the garden of Eden and the forests of Lebanon (possibly used symbolically) within prophetic writings.[13] Edward Lipinski and Peter Kyle McCarter have suggested that the Garden of the gods (Sumerian paradise), the oldest Sumerian version of the Garden of Eden, relates to a mountain sanctuary in the Lebanon and Anti-Lebanon ranges.[14]

Proposed locations

Persian Gulf

Juris Zarins believes that the Garden of Eden was situated at the head of the Persian Gulf, where the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers run into the sea, from his research on this area using information from many different sources, including Landsat images from space. In this theory, the Bible’s Gihon River would correspond with the Karun River in Iran, and the Pishon River would correspond to the Wadi Batin river system that once drained the now dry, but once quite fertile central part of the Arabian Peninsula.[15]

Tabriz

David M. Rohl (British Egyptologist and former director of the Institute for the Study of Interdisciplinary Sciences) posits a location for the legendary Garden of Eden in Iranian Azerbaijan, in the vicinity of Tabriz upon which the Genesis tradition was based. According to Rohl, the Garden of Eden was then located in a long valley to the north of Sahand volcano, near Tabriz. He cites several geographical similarities and toponyms which he believes match the biblical description. These similarities include the nearby headwaters of the four rivers of Eden, the Tigris (Heb. Hiddekel, Akk. Idiqlat), Euphrates (Heb. Perath, Akk. Purattu), Gaihun-Aras (Heb., Gihon), and Uizun (Heb. Pishon)[16]

Parallel concepts

- The city of Dilmun in the Sumerian mythological story of Enki and Ninhursag, is a paradisaical abode[17] of the immortals, where sickness and death were unknown.[18]

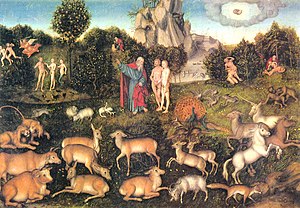

- The garden of the Hesperides in Greek mythology, was somewhat similar to the Christian concept of the Garden of Eden, and by the 16th century a larger intellectual association was made in the Cranach painting (see illustration at top). In this painting, only the action that takes place there identifies the setting as distinct from the Garden of the Hesperides, with its golden fruit.

- The Persian term "paradise" (Hebrew פרדס, pardes), meaning a royal garden or hunting-park, gradually became a synonym for Eden after c.500 BCE. The word "pardes" occurs three times in the Old Testament, but always in contexts other than a connection with Eden: in the Song of Solomon iv. 13: "Thy plants are an orchard (pardes) of pomegranates, with pleasant fruits; camphire, with spikenard"; Ecclesiastes 2. 5: "I made me gardens and orchards (pardes), and I planted trees in them of all kind of fruits"; and in Nehemiah ii. 8: "And a letter unto Asaph the keeper of the king's orchard (pardes), that he may give me timber to make beams for the gates of the palace which appertained to the house, and for the wall of the city." In these examples pardes clearly means "orchard" or "park", but in the apocalyptic literature and in the Talmud, "paradise" gains its associations with the Garden of Eden and its heavenly prototype, and in the New Testament "paradise" becomes the realm of the blessed (as opposed to the realm of the cursed) among those who have already died, with literary Hellenistic influences.

Religious views

Jewish eschatology

In the Talmud and the Jewish Kabbalah,[19] the scholars agree that there are two types of spiritual places called "Garden in Eden". The first is rather terrestrial, of abundant fertility and luxuriant vegetation, known as the "lower Gan Eden". The second is envisioned as being celestial, the habitation of righteous, Jewish and non-Jewish, immortal souls, known as the "higher Gan Eden". The Rabbanim differentiate between Gan and Eden. Adam is said to have dwelt only in the Gan, whereas Eden is said never to be witnessed by any mortal eye.[19]

According to Jewish eschatology,[20][21] the higher Gan Eden is called the "Garden of Righteousness". It has been created since the beginning of the world, and will appear gloriously at the end of time. The righteous dwelling there will enjoy the sight of the heavenly chayot carrying the throne of God. Each of the righteous will walk with God, who will lead them in a dance. Its Jewish and non-Jewish inhabitants are "clothed with garments of light and eternal life, and eat of the tree of life" (Enoch 58,3 - This citation is wrong.) near to God and His anointed ones.[21] This Jewish rabbinical concept of a higher Gan Eden is opposed by the Hebrew terms gehinnom[22] and sheol, figurative names for the place of spiritual purification for the wicked dead in Judaism, a place envisioned as being at the greatest possible distance from heaven.[23]

In modern Jewish eschatology, it is believed that history will complete itself and the ultimate destination will be when all mankind returns to the Garden of Eden.[24]

Islamic view

The Garden of Eden is spoken about prominently in the Quran and the tafsir (interpretation). This includes surat Sad, which features 21 verses on the subject, surat al-Baqarah, surat al-A'raf, and surat al-Hijr. The narrative mainly surrounds the expulsion of Iblis from the garden and his subsequent tempting of Adam and Eve. After Iblis refuses to follow God's command to bow down to Adam for being his greatest creation, Allah transforms him into Satan as a punishment. Unlike the Biblical account, the Quran mentions only one tree in Eden, the tree of immortality, which Allah specifically forbade to Adam and Eve. Satan, disguised as a serpent, repeatedly told Adam to eat from the tree, and eventually both Adam and Eve did so, thus disobeying Allah.[25] These stories are also featured in the Islamic hadith collections, including al-Tabari.[26]

Latter-day Saints

Members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (also known as Mormons or Latter-day Saints) believe that after Adam and Eve were expelled from the Garden of Eden they resided in a place known as Adam-ondi-Ahman, located in present-day Daviess County, Missouri. It is recorded in the Doctrine and Covenants that Adam blessed his posterity there and that he will return to that place at the time of the final judgement[27][28] in fulfillment of biblical prophecy.[29]

Numerous early leaders of the Church, including Brigham Young, Heber C. Kimball, and George Q. Cannon, taught that the Garden of Eden itself was located in nearby Jackson County, Missouri,[30] but there are no surviving first-hand accounts of that doctrine being taught by Joseph Smith himself. LDS doctrine is unclear as to the exact location of the Garden of Eden, but tradition among Latter-Day Saints places it somewhere in the vicinity of Adam-ondi-Ahman, or in Jackson County.[31][32]

Art

Garden of Eden motifs most frequently portrayed in illuminated manuscripts and paintings are the "Sleep of Adam" ("Creation of Eve"), the "Temptation of Eve" by the Serpent, the "Fall of Man" where Adam takes the fruit, and the "Expulsion". The idyll of "Naming Day in Eden" was less often depicted. Much of Milton's Paradise Lost occurs in the Garden of Eden. Michelangelo depicted a scene at the Garden of Eden in the Sistine Chapel ceiling. In the Divine Comedy, Dante places the Garden at the top of Mt. Purgatory. For many medieval writers, the image of the Garden of Eden also creates a location for human love and sexuality, often associated with the classic and medieval trope of the locus amoenus.[33]

See also

References

- ^ Gibson, Walter S. Hieronymus Bosch. New York: Thames and Hudson, 1973. p. 26. ISBN 0-500-20134-X

- ^ a b Cohen 2011, pp. 228–229

- ^ Luttikhuizen 1999, p. 37

- ^ H5731 Eden – The same as H5730 (masculine); Eden= "pleasure" ... the first habitat of man after the creation; site unknown

- ^ Davidson 1973, p. 33.

- ^ Donald Miller (2007) Miller 3-in-1: Blue Like Jazz, Through Painted Deserts, Searching for God, Thomas Nelson Inc, ISBN 978-1418551179, p. PT207

- ^ Stordalen 2000, p. 307–310.

- ^ "The Jewish Quarterly Review". The Jewish Quarterly Review. 64–65. University of Pennsylvania Press: 132. 1973. ISSN 1553-0604. Retrieved 2014-02-19.

... as Cossaea, the country of the Kassites in Mesopotamia [...]

- ^ Speiser 1994, p. 38

- ^ Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews. Book I, Chapter 1, Section 3.

- ^ Stordalen 2000, p. 164

- ^ Brown 2001, p. 138

- ^ Swarup 2006, p. 185

- ^ Smith 2009, p. 61

- ^ Hamblin, Dora Jane (May 1987). "Has the Garden of Eden been located at last?" (PDF). Smithsonian (magazine). 18 (2). Retrieved 8 January 2014.

- ^ Cline, Eric H. (2007). From Eden to Exile: Unraveling Mysteries of the Bible. National Geographic. p. 10. ISBN 978-1-4262-0084-7.

- ^ Mathews 1996, pp. 96.

- ^ Cohen 2011, pp. 229.

- ^ a b Gan Eden – JewishEncyclopedia; 02-22-2010.

- ^ Olam Ha-Ba – The Afterlife - JewFAQ.org; 02-22-2010.

- ^ a b Eshatology – JewishEncyclopedia; 02-22-2010.

- ^ "Gehinnom is the Hebrew name; Gehenna is Yiddish." Gehinnom – Judaism 101 websourced 02-10-2010.

- ^ "Gan Eden and Gehinnom". Jewfaq.org. Retrieved 2011-06-30.

- ^ "End of Days". End of Days. Aish. Retrieved 1 May 2012.

- ^ Leaman, Oliver The Quran, an encyclopedia, p. 11, 2006

- ^ Wheeler, Brannon Mecca and Eden: ritual, relics, and territory in Islam p. 16, 2006

- ^ [1]

- ^ [2]

- ^ [3]

- ^ “Joseph Smith/Garden of Eden in Missouri”, FairMormon Answers

- ^ Bruce A. Van Orden, “I Have a Question: What do we know about the location of the Garden of Eden?”, Ensign, January 1994, pp. 54–55.

- ^ http://www.mormonnewsroom.org/article/mormonism-101#C18 “Mormonism 101: FAQ”

- ^ Curtius 1953, p. 200,n.31

Bibliography

- Brown, John Pairman (2001). Israel and Hellas, Volume 3. Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 9783110168822.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Cohen, Chaim (2011). "Eden". In Berlin, Adele; Grossman, Maxine (eds.). The Oxford Dictionary of the Jewish Religion. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199730049.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Curtius, Ernst Robert (1953). European Literature and the Latin Middle Ages. Princeton UP. ISBN 978-0-691-01899-7.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Davidson, Robert (1973). Genesis 1-11 (commentary by Davidson, R. 1987 [Reprint] ed.). Cambridge, Eng.: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521097604.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Mathews, Kenneth A. (1996). Genesis. Nashville, Tenn.: Broadman & Holman Publishers. ISBN 9780805401011.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Smith, Mark S. (2009). "Introduction". In Pitard, Wayne T. (ed.). The Ugaritic Baal Cycle, volume II. BRILL. ISBN 9004153489.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Speiser, E.A. (1994). "The Rivers of Paradise". In Tsumura, D.T.; Hess, R.S. (eds.). I Studied Inscriptions from Before the Flood. Eisenbrauns. ISBN 9780931464881.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Stordalen, Terje (2000). Echoes of Eden. Peeters. ISBN 9789042908543.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Swarup, Paul (2006). The self-understanding of the Dead Sea Scrolls Community. Continuum.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)