Joseph Bazalgette: Difference between revisions

WP:CHECKWIKI error fix. Broken bracket problem. Do general fixes and cleanup if needed. - using AWB |

Cyberbot II (talk | contribs) Rescuing 1 sources, flagging 0 as dead, and archiving 5 sources. (Peachy 2.0 (alpha 8)) |

||

| Line 64: | Line 64: | ||

A [[Greater London Council]] [[blue plaque]] commemorates Bazalgette at 17 Hamilton Terrace in St John's Wood in North London,<ref name='EngHet'>{{cite web| url=http://www.english-heritage.org.uk/discover/blue-plaques/search/bazalgette-sir-joseph-william-1819-1891|title=BAZALGETTE, SIR JOSEPH WILLIAM (1819–1891)|publisher=English Heritage| accessdate=20 October 2012}}</ref> while a formal monument on the riverside of the Victoria Embankment in central London commemorates Bazalgette. |

A [[Greater London Council]] [[blue plaque]] commemorates Bazalgette at 17 Hamilton Terrace in St John's Wood in North London,<ref name='EngHet'>{{cite web| url=http://www.english-heritage.org.uk/discover/blue-plaques/search/bazalgette-sir-joseph-william-1819-1891|title=BAZALGETTE, SIR JOSEPH WILLIAM (1819–1891)|publisher=English Heritage| accessdate=20 October 2012}}</ref> while a formal monument on the riverside of the Victoria Embankment in central London commemorates Bazalgette. |

||

[[Dulwich College]] has a scholarship in his name, for design and technology<ref>[http://www.dulwich.org.uk/client_files/doc_docs/MastersReport04-05.pdf ]{{ |

[[Dulwich College]] has a scholarship in his name, for design and technology<ref>[http://www.dulwich.org.uk/client_files/doc_docs/MastersReport04-05.pdf ] {{wayback|url=http://www.dulwich.org.uk/client_files/doc_docs/MastersReport04-05.pdf |date=20071217215803 |df=y }}</ref> or for mathematics and science.<ref>[http://www.dulwich.org.uk/client_files/doc_docs/Academic/MastersReportGovernors2006-07.pdf Dulwich.org.uk]{{dead link|date=December 2011}}</ref> |

||

==Other works== |

==Other works== |

||

Revision as of 09:19, 18 October 2015

This article needs additional citations for verification. (May 2012) |

Joseph Bazalgette | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Joseph William Bazalgette 28 March 1819 Clay Hill, Enfield, London, England |

| Died | 15 March 1891 (aged 71) Wimbledon, London, England |

| Occupation | Civil engineer |

Sir Joseph William Bazalgette, CB (/ˈbæzəldʒɛt/; 28 March 1819 – 15 March 1891) was a 19th-century English civil engineer. As chief engineer of London's Metropolitan Board of Works his major achievement was the creation (in response to the Great Stink of 1858) of a sewer network for central London which was instrumental in relieving the city from cholera epidemics, while beginning the cleansing of the River Thames.[1]

Early life

Bazalgette was born at Hill Lodge, Clay Hill, Enfield, London, the son of Joseph William Bazalgette (1783–1849), a retired Royal Navy captain, and Theresa Philo, née Pilton (1796–1850), and was the grandson of a French Protestant immigrant.

He began his career working on railway projects, articled to noted engineer Sir John MacNeill and gaining sufficient experience (some in Ireland) in land drainage and reclamation works for him to set up his own London consulting practice in 1842. By the time he married his wife, Maria Kough, in 1845, Bazalgette was deeply involved in the expansion of the railway network, working so hard that he suffered a nervous breakdown two years later.

While he was recovering, London's short-lived Metropolitan Commission of Sewers ordered that all cesspits should be closed and that house drains should connect to sewers and empty into the Thames. As a result, a cholera epidemic (1848–49) killed 14,137 Londoners.

Bazalgette was appointed assistant surveyor to the Commission in 1849, taking over as Engineer in 1852, after his predecessor died of "harassing fatigues and anxieties." Soon after, another cholera epidemic struck, in 1853, killing 10,738. Medical opinion at the time held that cholera was caused by foul air: a so-called miasma. Physician Dr John Snow had earlier advanced a different explanation, which is now known to be correct: cholera was spread by contaminated water. His view was not then generally accepted.

Championed by fellow engineer Isambard Kingdom Brunel, Bazalgette was appointed chief engineer of the Commission's successor, the Metropolitan Board of Works, in 1856 (a post which he retained until the MBW was abolished and replaced by the London County Council in 1889). In 1858, the year of the Great Stink, Parliament passed an enabling act, in spite of the colossal expense of the project, and Bazalgette's proposals to revolutionise London's sewerage system began to be implemented. The expectation was that enclosed sewers would eliminate the stink ('miasma'), and that this would then reduce the incidence of cholera.

Sewer works

The scheme involved major pumping stations at Deptford (1864) and at Crossness (1865) on the Erith marshes, both on the south side of the Thames, and at Abbey Mills (in the River Lea valley, 1868) and on the Chelsea Embankment (close to Grosvenor Bridge; 1875), north of the river.

The system was opened by Edward, Prince of Wales in 1865, although the whole project was not actually completed for another ten years.

Bazalgette's foresight may be seen in the diameter of the sewers. When planning the network he took the densest population, gave every person the most generous allowance of sewage production and came up with a diameter of pipe needed. He then said 'Well, we're only going to do this once and there's always the unforeseen' and doubled the diameter to be used. His foresight allowed for the unforeseen increase in population density with the introduction of the tower block; with the original, smaller pipe diameter the sewer would have overflowed in the 1960s, rather than coping until the present day as it has.

The unintended consequence of the new sewer system was to eliminate cholera everywhere in the water system, whether or not it stank. The basic premise of this expensive project, that miasma spread cholera infection, was wrong. However, instead of causing the project to fail, the new sewers succeeded in virtually eliminating the disease by removing the contamination. Bazalgette's sewers also decreased the incidence of typhus and typhoid epidemics.[2]

Bazalgette's capacity for hard work was remarkable; every connection to the sewerage system by the various Vestry Councils had to be checked and Bazalgette did this himself and the records contain thousands of linen tracings with handwritten comments in Indian ink on them "Approved JWB", "I do not like 6" used here and 9" should be used. JWB", and so on. It is perhaps not surprising that his health suffered as a result. The records are held by Thames Water in large blue binders gold-blocked reading "Metropolitan Board of Works" and then dated, usually two per year.

Private life

Bazalgette lived in 17 Hamilton Terrace, St John's Wood, north London for some years. Before 1851, he moved to Morden, then in 1873 to Arthur Road, Wimbledon, where he died in 1891, and was buried in the nearby churchyard at St Mary's Church.

In 1845 at Westminster, he married Maria Kough (1819–1902). Lady Bazalgette died at her residence in Wimbledon on 3 March 1902.[3] They had children including:

- Joseph William, born 20 February 1846

- Charles Norman, born 3 March 1847

- Edward, born 28 June 1848

- Theresa Philo, born 1850

- Caroline, born 17 July 1852

- Maria, born 1854

- Henry, born 14 September 1855

- Willoughby, born 1857

- Maria Louise, born 1859

- Anna Constance, born 3 December 1859

- Evelyn, born 1 April 1861

Awards and memorials

Bazalgette was knighted in 1875, and elected President of the Institution of Civil Engineers in 1883.

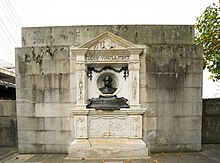

A Greater London Council blue plaque commemorates Bazalgette at 17 Hamilton Terrace in St John's Wood in North London,[4] while a formal monument on the riverside of the Victoria Embankment in central London commemorates Bazalgette.

Dulwich College has a scholarship in his name, for design and technology[5] or for mathematics and science.[6]

Other works

- Albert Embankment (1869)

- Victoria Embankment (1870)

- Chelsea Embankment (1874)

- Maidstone Bridge (1879)

- Albert Bridge (1884; modifications)

- Putney Bridge (1886)

- Hammersmith Bridge (1887)

- The Woolwich Free Ferry (1889)

- Battersea Bridge (1890)

- Charing Cross Road

- Garrick Street

- Northumberland Avenue

- Shaftesbury Avenue

- Early plans for the Blackwall Tunnel (1897)

- Proposal for what later became Tower Bridge

Notable descendants

- Ian Bazalgette (great-grandson), RAF pilot awarded a Victoria Cross

- Peter Bazalgette (great-great-grandson), television producer

- Simon Bazalgette (great-great-grandson), chief executive of The Jockey Club

- Edward Bazalgette (great-great-grandson), television director

References

- ^ Halliday, Stephen (2013). The Great Stink of London: Sir Joseph Bazalgette and the Cleansing of the Victorian Metropolis. The History Press. ISBN 0752493787.

- ^ "'Dirty Old London': A History of the Victorians' Infamous Filth". NPR. 12 March 2015. Retrieved 13 March 2015.

[the famous great sewer network of the mid-19th century] basically took away the possibility of wholesale cholera epidemics in the city, typhus and typhoid – they all were reduced.

- ^ "Obituary – Lady Bazalgette". The Times. No. 36706. London. 4 March 1902. p. 8. template uses deprecated parameter(s) (help)

- ^ "BAZALGETTE, SIR JOSEPH WILLIAM (1819–1891)". English Heritage. Retrieved 20 October 2012.

- ^ [1] Archived 2007-12-17 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Dulwich.org.uk[dead link]

Further reading

- . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911.

- Sir Joseph William Bazalgette (1819–1891): Engineer to the Metropolitan Board of Works – D P Smith: Transactions of the Newcomen Society, 1986–87 Vol 58.

- London in the Nineteenth Century: A Human Awful Wonder of God – Jerry White, London: Jonathan Cape 2006.

- The Big Necessity: Adventures in the world of human waste by Rose George, Portobello Books, ISBN 978-1-84627-069-7. book review (subscription needed for whole article) in New Scientist

- Beare, Thomas Hudson (1901). . In Lee, Sidney (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography (1st supplement). London: Smith, Elder & Co.

- Smith, Denis. "Bazalgette, Sir Joseph William (1819–1891)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/1787. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

External links

- BBC biography

- Newcomen Society paper (from Internet Archive)

- Battersea Bridge

- Crossness Pumping Station

- Bazalgette family tree

- 1819 births

- 1891 deaths

- British people of Huguenot descent

- Companions of the Order of the Bath

- English architects

- English civil engineers

- English people of French descent

- Water supply and sanitation in London

- Presidents of the Institution of Civil Engineers

- Presidents of the Smeatonian Society of Civil Engineers

- Thames Water

- Metropolitan Board of Works

- People from Enfield (London borough)