Paradise Lost: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

|||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{otheruses|Paradise Lost (disambiguation)}} |

{{otheruses|Paradise Lost (disambiguation)}} |

||

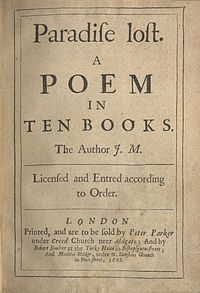

[[Image:milton paradise.jpg|thumb|200px|Title page of the first edition]] |

[[Image:milton paradise.jpg|thumb|200px|Title page of the first edition]] |

||

'''''Paradise Lost'''''<!-- Paradiſe Loſt --> is an [[epic poem]] by the 17th-century [[England|English]] poet [[John Milton]]. It was originally published in [[1667]] in ten books and written in [[blank verse]]. A second edition followed in [[1674]], redivided into twelve books (mimicking the division of [[Virgil]]'s ''[[Aeneid]]'') with minor revisions throughout and a note on the versification. The poem concerns the [[Christianity|Christian]] story of the [[Fall of Man]]: the temptation of [[Adam and Eve]] by [[Satan]] and their expulsion from the [[Garden of Eden]]. |

'''''Paradise Lost'''''<!-- Paradiſe Loſt --> is an [[epic poem]] by the 17th-century [[England|English]] poet [[John Milton]]. It was originally published in [[1667]] in ten books and written in [[blank verse]]. A second edition followed in [[1674]], redivided into twelve books (mimicking the division of [[Virgil]]'s ''[[Aeneid]]'') with minor revisions throughout and a note on the versification. The poem concerns the [[Christianity|Christian]] story of the [[Fall of Man]]: the temptation of [[Adam and Eve]] by [[Satan]] and their expulsion from the [[Garden of Eden]]. Milton's (stated purpose in Book I) is to justify the ways of God and the conflict between the eternal [[foresight]] of God and [[free will]]. |

||

==Main characters== |

==Main characters== |

||

Revision as of 19:12, 28 November 2006

Paradise Lost is an epic poem by the 17th-century English poet John Milton. It was originally published in 1667 in ten books and written in blank verse. A second edition followed in 1674, redivided into twelve books (mimicking the division of Virgil's Aeneid) with minor revisions throughout and a note on the versification. The poem concerns the Christian story of the Fall of Man: the temptation of Adam and Eve by Satan and their expulsion from the Garden of Eden. Milton's (stated purpose in Book I) is to justify the ways of God and the conflict between the eternal foresight of God and free will.

Main characters

Satan

Modern readers may consider Satan to be the hero of the story, since he struggles to overcome his own doubts and weaknesses and accomplishes his goal of corrupting mankind. The Romantics, not Milton himself, probably launched the notion of Satan's being the hero. Taine describes Milton's Satan as follows:

'The ridiculous Devil of the Middle Ages, a horned enchanter, a dirty jester, a petty and mischievous ape, band-leader to a rabble of old women, has become a giant and a hero'. 'Though feebler in force, he remains superior in nobility, since he prefers suffering independence to happy servility, and welcomes his defeat and his torments as a glory, a liberty, and a joy'. [citation needed]

Satan is far from being the story's object of admiration. Satan is, however, the most intriguing and compelling of the characters, mainly for his complexity and subtlety. In these regards, he is similar to the character of Iago in Shakespeare's Othello. (This could also be considered along the lines of an antihero.)

There is, however, an academic current — most notably advanced by Stanley Fish — that claims that Milton's presentation of Satan as an apparent hero at the beginning of the story, whose independence and emotional character contrasts sharply with the denizens of heaven, is a deliberate attempt by Milton to draw readers into sympathizing with Satan against their will, thereby demonstrating the seductive power of evil.[citation needed] It is worth noting, for example, that although Satan holds a forum for debate at the start of the story, it ultimately ends with Satan's second in command acting as a mouthpiece for Lucifer, and deceiving them into undertaking a course of action which establishes Satan's dominance. This seems to suggest a common theme in Puritanical writing that, while the freedom to do evil may appear tantalizing, it ultimately leads only to self destruction and slavery. Thus, Satan and his fallen angels can be interpreted to offer an overall critique of society and a justification of the Puritan commonwealth's attempts to ban actions deemed immoral.

Another academic current claims that Satan's role as the hero, mimics Achilles's injured merit, Odysseus's wiles and craft, and Aeneas's journey to find a new homeland.[citation needed] Others claim that Milton personifies in Satan the spirit of the English Revolution, of Oliver Cromwell, that Milton's Satan represents the honor and independence of the nation asserted in the face of an incapable government.[citation needed]

First known by a name that was blotted out in Heaven's "book of life," but associated with Lucifer, the morningstar, he was a proud archangel who failed to think of himself as equal to the other angels. The day God pronounces the Son as second in power, Lucifer rebels out of envy, taking with him a third of all the population of angels in Heaven. He is extremely proud and confident that he can overthrow God; his speeches are always fraudulent and deceitful. He assumes many forms during the story, which are reflective of his moral and rational degradation. First, he is a fallen angel of enormous stature; then a humble cherub; a cormorant; a toad; and finally, a snake. He is a picture of incessant intellectual activity without the ability to think morally. He is also weak and helpless, and is unable to stand up to the angels remaining faithful to God. Once a powerful angel, he has become blinded to God's grace, forever unable to reconcile his past with his eternal punishment.

Adam and Eve

Adam is strong, intelligent and rational, made for contemplation and valor, and before the fall, as perfect as a human being could be. He is flawed however, and at times indulges in rash and irrational attitudes. His pure reason and intellect are lost as a result of the fall, Man never being able again to converse with angels as near-equal (as he did with Raphael) but forever one-sided (as he did with Michael after the fall). His weakness is that he allows his sexual passion for Eve to take precedence over his love for, and belief in, God. He confides to Raphael that his attraction to her is almost overwhelming – something that Adam's reason is unable to overcome. After Eve eats from the Tree of Knowledge, he decides to do the same, realizing that if she is doomed, he must follow her into doom as to not lose her - even if that means disobeying God.

Eve is the mother of all mankind, inferior to Adam, considered to be closer to God, made for softness and "sweet attractive Grace." (Book IV, 297-299) She only surpasses him in beauty, beauty as such she even falls in love with her own image upon seeing her reflection in a body of water (a reference to the Greek myth of Narcissus). It is her vanity that Satan taps into in order to persuade her to eat from the Tree of Knowledge, through flattery. Eve is clearly intelligent but unlike Adam she is not eager to learn, being absent from Adam and Raphael's conversation in Book VIII, and Adam's visions presented by Michael in Books XI and XII. Eve does not feel it is her place to seek knowledge independently, as she prefers to have Adam teach her later. The one instance in which she deviates from this passiveness is when she goes out on her own and ends up seizing the fruit of the Tree of Knowledge.

Through Eve, Milton explores the role of women in his society and the positive and important role they could offer in the divine union of marriage, as the "helpmeet" to the husband. At the end of the poem, after exposing their strengths and weaknesses, Adam and Eve emerge as a powerful unit, complementary in each other – not only to the reader, but to themselves. The fall serves a purpose of self-discovery, the Fortunate Fall, or felix culpa.

God, the Father

Milton's God is omniscient (has all-encompassing knowledge), omnipresent (is everywhere at once) and omnipotent (all-powerful), and is also predestinate – which coexists with and complements man's free will. God is aloof, almost emotionless. He embodies pure reason, and consequently his responses often seem cold. The problem with interpreting the character of God in Paradise Lost is that he is more of a personification of abstract ideas than a real character. He allows evils to occur, but in order to make good out of that evil.

The Son (Christ prior to his incarnation)

The Son is the manifestation of God in action, the physical connection between God the Father and his creation, together forming a complete and perfect God. He personifies love and compassion and volunteers to die for humankind in order to redeem them, showing his dedication and selflessness. Through his human form the Son will be descended from Adam, through whom all men died, but He will be a second Adam, by whom all men shall be saved. In Judgment Day, the Son will appear in the sky and have dead summoned from every corner of the world, sentencing the sinners to Hell. Adam's final vision in Book XII is of the Son's sacrifice as Jesus. It is important to note that this section has been labelled "The Son" because He is not yet Jesus Christ, whom he will be known as only after his incarnation. Milton takes a view held by some Christians that the Son was instrumental in the Creation of the world and humanity; this can be compared with the more "modern" belief of God the Father as Creator, and Christ as the redeemer- part of God the Father, but the creative force of the Trinity.

Story

The story is divided into twelve books against Homer's twenty-four books of the Iliad and Odyssey. The longest book is Book IX, with 1189 lines and the shortest, Book VII, with 640. Each book is preceded by an argument, a summary of the book's contents. (The arguments were not included in the first issue of Paradise Lost, but added on later by Milton, according to him, "for the satisfaction of many that have desired it.") The poem follows the epic tradition of starting in medias res (Latin for in the midst of things), the background story being told in Books V-VI.

Book I

The action begins with Satan and his rebel angels, chained to a lake of fire in Hell. Once freed, they fly to land, gather minerals and build Pandæmonium, the capital of Hell (also the palace of Satan). There they hold a debate on what to do next in relation to the war in Heaven.

Book II

Moloch, a fierce devil who wishes to be equal to God or annihilated in the struggle, argues for open war. Belial advises the council to wait and see. Mammon suggests that they make the best of their situation in Hell, dismissing war altogether. Beelzebub, Satan's chief accomplice, suggests that the best way to attack God would be corrupting His new creation: humankind. Satan, who had conceived the idea in the first place, agrees and volunteers to go himself.

At the gates of Hell, Satan is met by two children: Sin, a girl, and Death, a boy. Sin reveals to Satan that he is her father, and after he had sex with her, she produced Death. Death's violent birth changes Sin's bottom-half of her body into that of a snake. Death's first act of life is to rape his Mother, thus impregnating her again. This time, Sin births the terrible hellhounds that follow her everywhere and return into her womb periodically to gnaw at her entrails. Sin holds the key to the locked gate of Hell, which she opens for her father, releasing him from his prison. Once opened, these gates cannot be shut, forever opening the doors of Hell to the rest of creation. Satan goes through the realm of Chaos and his consort Old Night. Chaos is pleased with Satan's plan and directs him to Earth, which is suspended from Heaven by a golden chain in the regions above.

It is in these first books that Satan is at his most noble: He is described in grandiose terms--as a giant, physically larger than the Titans of Greco-Roman mythology. Like the ancient epics of Homer, Paradise Lost begins in media res (just after the rebellion in heaven ends), just as the Iliad begins in the middle of a long war.

Book III

God the Father sits on his throne in Heaven and predicts to the Son that Satan will tempt man, but it will be man's fault if he disobeys God since man was made "Sufficient to have stood, though free to fall". However, whereas the evil angels fell by their own suggestion, man falls because he is tempted by Satan, and that is why he will be able to find mercy and grace. The Son volunteers to sacrifice himself in order to redeem humankind. Meanwhile Satan is traveling and comes upon a stairway up to Heaven and a stairway down to Paradise. He has a vision of the whole universe that fills him with wonder and envy. Further on Satan discovers Uriel, the angel of the Sun, and disguises himself as a "stripling cherub" and tells Uriel he wishes to see and praise God's glorious creation and Uriel points out Earth and Paradise for him.

Books IV-V

Landing on Earth, Satan takes a moment to reflect, leading to a famous speech about the sun. He is troubled because wherever he goes, he carries Hell around with him in his mind and cannot escape it. Paradise brings him pain rather than pleasure and he reaffirms his decision to make evil his good. Satan leaps over the wall of Eden, like a wolf jumping into a sheepfold; and disguised as a cormorant, he perches himself atop the Tree of Life, and there plots death for man. He sees Adam and Eve for the first time, the natural king and queen of their world, in complete harmony with their surroundings, returning to their bower to rest after a long day of work. Adam and Eve talk about God and from their conversation Satan learns of the existence of the Tree of Knowledge, from which they are forbidden to eat. He takes the form of a toad and whispers into Eve's ear, giving her an evil dream that foreshadows the fall, in which an angel tempts her to eat from the Tree.

Earlier on Uriel had noticed a change in Satan's appearance and called Gabriel to deal with the impostor, who orders Satan to leave. God sends down Raphael to teach man of the dangers they are facing so that they do not fall from ignorance. The next morning Raphael arrives on Earth and has a meal with Adam and Eve, indicating the possibility of easy give and take between angels and Man before the fall. Raphael then tells the story of Satan's envy over the Son's appointment as God's second-in-command. Satan influenced many other angels into siding with him and plotted a war against God. The angel Abdiel tried to convince Satan that the Son's reign over the hierarchy of angels will give it more glory and make it more secure. Even though he is right, no one had the courage to support him, and he returned to God.

Books VI-VIII

Raphael continues his story, recounting the following day as war preparations had begun, and Abdiel called Satan a fool not to recognize that it is useless to fight against God's omnipotence. The battle lasted two days, when God sent the Son to end the war and deliver Satan and his rebel angels to Hell. Raphael ends his account by warning Adam about Satan's evil motives to corrupt them. Adam asks Raphael to tell him the story of creation. After Lucifer had fallen from Heaven, God announced his intention of creating a race of beings to repopulate Heaven in the place of the fallen angels. He sent the Son to set boundaries on Chaos and created the earth, and stars and other planets, following the account in Genesis.

Still curious, Adam asks Raphael about the movement of heavenly bodies. The angel answers that it should not matter to man, God conceals that and other things that are not necessary for man to know. Adam decides to tell Raphael of his own story, of waking up and wondering who he was, what he was, and where he was. God spoke to him and told him many things, including his order not to eat from the Tree of Knowledge. Adam asked God for a companion, because the animals who live in Paradise are not his equals. He took out a rib from Adam, from which he formed Eve. He explains his intense physical attraction to her, but Raphael reminds him that he must love her more purely and spiritually.

Book IX

Seven days later, Satan returns to Paradise. After studying closely the animals of Paradise, he chooses to take the form of the serpent, the "subtlest beast of all the field". Meanwhile Eve suggests to Adam that they should work separately for a while. Adam, having Raphael's warning in mind, is hesitant, but then agrees. Eve does not think a foe so proud will attack the weaker person first. Satan finds her alone, and in the form of a serpent, talks and compliments her on her beauty and godliness. She is amazed that the animal can speak, and he explains that he has risen from his animal state by eating from a certain tree, that gave him the ability to reason and talk. Upon seeing the tree, Eve recognizes it and tells the serpent that it is forbidden. The serpent argues that they have been wronged by God, and that the fruit will give them wisdom and god-like status, and God wants to keep this knowledge for Himself.

She is hesitant but reaches for a fruit and eats, and the serpent quickly disappears into the woods. Eve is distraught and searches for Adam, who has been busy making her a wreath of flowers. He is horrified to learn that she has disobeyed God, realizing that she is lost, and he with her. Realizing that he would rather be fallen with her than remain pure and lose her, he eats the fruit as well. Utterly caught up in their actions, thoughtless and intoxicated, they give in to lust and display for the first time ugly passions such as hate, anger and mistrust. (Here, as elsewhere, Milton reads much into the account given in Genesis.)

Book X

God tells the angels in Heaven that Adam, Eve, and Satan must be punished, but with justice and mercy. First the serpent is punished, condemned to never walk upright again. Then Adam and Eve are sentenced to pain and death. Eve and all the women must suffer the pain of childbirth and submit to their husbands, whereas Adam and all men must work, hunt, and grow their own food. The Son gives them clothes out of pity, given that now they are ashamed of their nakedness.

On his way back to Hell, Satan meets Sin and Death, who travel to Earth, making a bridge over Chaos. At Pandæmonium, he is greeted with cheers, but shortly thereafter the devils are unwillingly transformed into snakes and are tempted to reach a fruit from trees that turn to dust as they reach them. God tells the angels to transform the Earth. After the fall, mankind must suffer hot and cold seasons instead of the consistent temperatures before the fall. On Earth, Adam and Eve fear their approaching doom and blame each other for their disobedience and become increasingly angry at one another. Adam even wonders why God ever created Eve, who begs him not to abandon her. They contemplate suicide, but realize that they can enact revenge on Satan by remaining obedient to God, and together pray to God and repent.

Books XI-XII

God hears their prayers and forgives them, but will not allow man to live in Paradise any longer: the immortal elements of Paradise reject Adam and Eve who are now mortal. Michael arrives on Earth and tells them they must leave. But before that he puts Eve to sleep and takes Adam to the top of the highest hill in Paradise, where he shows him a vision of the future of mankind. Adam sees the sins of his children, Cain and Abel, and of all his progeny. He is horrified with visions of death, lust, greed, envy, and pride. They kill each other selfishly and live only for pleasure. Then there is Enoch, who is saved by God as his warring peers attempt to kill him; Noah and his family, whose virtue allows them to be chosen to survive the Flood. God punishes Ham and his sons. Then there is the hunter Nimrod and the Tower of Babel he builds to reach Heaven; the triumph of Moses and the Israelites, and finally the Son’s sacrifice to save man. Adam realizes that this is all the knowledge he needs to have, knowing he must obey God and depend on Him. All he needs to do is to add facts of faith, virtue, patience, temperance and love to his knowledge and he will find within himself a paradise far happier than the one he is now in. Led by Michael, Adam and Eve slowly and woefully leave Paradise hand in hand into a new world.

Paradise Regained

Less well-known is Milton's sequel to Paradise Lost, Paradise Regained. This poem is shorter than Paradise Lost (four books as compared with twelve) and deals with the New Testament story of salvation, and is centred around Jesus' temptation by the Devil in the desert.

Precursors and source materials

Influences include the Bible, Milton's unorthodox religious perspective, Edmund Spenser, Homer, Ovid, Herodotus, the Roman poet Virgil, Dante, and ancient mythologies such as those of Greece, Rome, the Islamic world, etc. Another prominent, yet seemingly esoteric figure in the origination of this writing is Plato's Republic: Book VIII. Some scholars have noted an interesting similarity between Paradise Lost and the Old English translation of Genesis. At this point, scholars are unsure if Milton had the Old English manuscripts in his possession, or even if he would have been able to read the Old English Genesis, as the language was already profoundly different from his 17th century Early Modern English. More concrete are the similarities in language in several points with the Authorised version of the Bible. Interestingly, Milton also read the Old Testament in its original Hebrew.

It has been suggested that Milton drew inspiration from Joost van den Vondel's Lucifer, but this seems doubtful. Although the similarities in the works are clear, and Milton knew some Dutch, as Roger Williams taught him this, it seems doubtful that he knew enough to be able to read the plays, and English translations did not exist at that time.

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. |

Thematic concerns

The Trinity – Milton's interpretation of the Trinity is that the Son and Spirit are both parts of God, or aspects of God, but they are not all of God. The analogy Milton makes in Paradise Lost is one of light: God is like the sun, the essence of light, while the Son is like the rays of the sun, an "effluence" of light. Just as it is difficult to separate the sun from its rays, it is difficult for Milton to separate the Son from the Father, or the Spirit from the other parts of the Trinity.

Also, some critics have argued that the Muse the narrator calls upon for help in the beginning of book one is the third part of God, the Holy Spirit, therefore, completing the trinity.

Moreover, there is a sort of anti-Trinity to be found in Satan, Sin and Death, as described in the second book. Satan is the "Father" (v. 727), Death is his "only Son"" (v. 728), and Sin is a spirit which literally "issued forth" from Satan and which had a role to play in the birth of the Death.

Milton's poem also bears resemblance to the apocryphal Book of Enoch, which describes the fall of one third of a particular host of angels, including one (Azazel) who later became a folk devil in Judaic lore. Whether Milton was familiar with the work is unknown.

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. |

Response and criticism

This epic has generally been considered one of the greatest works in the English language. Since it is based upon scripture, its significance in the Western canon has been thought by some to have lessened due to increasing secularism. However, this is not the general consensus, and even academics who have been labeled as secular realize the merits of the work. In William Blake's The Marriage of Heaven and Hell, the "voice of the devil" argues:

- The reason Milton wrote in fetters when he wrote of Angels & God, and at liberty when of Devils & Hell, is because he was a true Poet and of the Devil's party without knowing it.

This statement became the most common reinterpretation of the work in the twentieth century, but among some critics such as C.S. Lewis, there is no such reinterpretation. Rather, such critics would uphold the theology of Paradise Lost insofar as it conforms to the passages of Scripture on which it is based.

The latter half of the twentieth century saw the critical understanding of Milton's epic shift to a more political and philosophical focus. Rather than the Romantic conception of the Devil as the hero of the piece, it is generally accepted that Satan is presented in terms that begin classically heroic, then diminish him until he is finally reduced to a dust-eating serpent unable even to control his own body. The political angle enters into consideration in the underlying friction between Satan's conservative, hierarchical views of the universe and the contrasting "new way" of God and the Son of God as illustrated in Book III. In contemporary critical theory in other words, the main thrust of the work becomes not the perfidy or heroism of Satan, but rather the tension between classical conservative "old testament" hierarchs (evidenced in Satan's worldview, and even in that of the archangels Raphael and Gabriel), and "new testament" revolutionaries (embodied in the Son of God, Adam, and Eve) who represent a new system of universal organization based not in tradition, precedence, and unthinking habit, but in sincere and conscious acceptance of faith on the one hand, and on station chosen by ability and responsibility. Naturally, this critical mode makes much use of Milton's other works and his biography, grounding itself in his personal history as an English revolutionary and social critic.

Classical music

Milton's Paradise Lost was, apart from straight quotations of biblical texts, the basis on which the libretto for Joseph Haydn's oratorio Die Schöpfung (The Creation) was built, by, among others, Baron van Swieten.

Influence on contemporary works

Paradise Lost has had a profound impact on writers, artists and illustrators, and, in the twentieth century, filmmakers.

- It influenced Mary Shelley when she wrote her seminal work, Frankenstein, in the 1810s; she included a quotation from book X on the title page, and it is one of three books Frankenstein's daemon finds which influences his psychological growth.

- In the late 1970s, the Polish composer Krzysztof Penderecki wrote an opera based on Paradise Lost, and Sergei Eisenstein thought it perfect material for epic film.

- The epic was also one of the inspirations for Philip Pullman's trilogy of novels His Dark Materials. In Pullman's introduction, he adapts Blake's line to quip that he himself "is of the Devil's party and does know it."

- The American composer Derek Strykowski used Paradise Lost as the basis for his Symphony No. 1: His Dark Materials.

- The Australian singer-songwriter Nick Cave has quoted from Paradise Lost many times in his lyrics.

- The British metal band Cradle Of Filth was inspired by Paradise Lost and wrote the album Damnation and a Day which takes place over the fall and eventual rise of Lucifer, another British metal band, Paradise Lost (band), takes its name directly from the poem's title.

- In the 1994 movie The Crow, a line from Book IV of Paradise Lost (line 846) plays an important role in the death of one of the film's villains, T-Bird; "Abasht the Devil stood, and felt how awful goodness is."

- In the 1995 movie Se7en, the first message left by the serial killer was a quotation from Paradise Lost: "Long is the way, and hard, that out of hell leads up to light."

- In the 1997 movie The Devil's Advocate, the senior board member of the New York based law firm is Lucifer and aptly uses the name "John Milton".

- Norwegian black metal band Dimmu Borgir quote Paradise Lost in the song "Architecture of a Genocidal Nature" in their album Puritanical Euphoric Misanthropia, released in 2001.

- (((SPOILER)))In the 2000 cyberpunk-action-roleplaying-game Deus Ex, all the three different ends possible has a famous quote accompanying them. The end where the hero of the game, JC Denton destroys Bob Page and gives the Illuminati world-dominance, is accompanied by the phrase: "It is better to reign in hell than serve in heaven"; Line 263 of book 1 in Paradise Lost, and tells the player that perhaps giving Illuminati world-dominance wasn't the most farsighted descision after all.

- A musical adaptation of Paradise Lost was written by Ben Birney and Rob Seitelman and was performed in New York City in March 2006. This sung-through musical augmented the main story of Paradise Lost with the addition of the character 'Sophia' who represented the feminine divine. It explored her relationship to the events of the Milton poem and offered explanation as to her virtual elimination from Canonic text.

Iconography

The history of illustrators includes, among others, Edward Burney, Richard Westall, Francis Hayman, Bernard Lens, and John Medina. The most notable and popular illustrators include William Blake, Gustave Dore and Henry Fuseli. The tradition continues today with noted surreal/visionary artist Terrance Lindall's rendition which was published in hardcover in 1982 and which also appeared in Heavy Metal Magazine around that time. Lindall's version [1] is taught at New York University and is considered to be the twentieth century's most notable contribution to the tradition of fine art illustrations in homage to Milton's visionary genius.

Selected bibliography

Online editions

Paradise Lost

- The Milton Reading Room XHTML version at Dartmouth

- Project Gutenberg text version 1

- Project Gutenberg text version 2

In print

- Paradise Lost Norton Critical Edition (2nd edition edited by Scott Elledge ISBN 0-393-96293-8; 3rd edition edited by Gordon Teskey ISBN 0-393-92428-9) – includes biographical, historical, and literary backgrounds, and criticism

- Paradise Lost Penguin Classics ISBN 0-14-042439-3

- Paradise Lost and Paradise Regained Signet Classic Poetry ISBN 0-451-52792-5

- Hughes, Merrit Y. ed. John Milton. Complete Poems and Major Prose. New York, 1957.

- Fowler, Alastair, ed. Paradise Lost 2nd Edition, Longman, London, 1998. ISBN 0-582-21518-8

- Paradise Lost and Other Poems, Signet Classic (Penguin Group), with introduction by Edward M. Cifelli, Ph.D. and notes by Edward Le Comte. New York, 2000.

References

- Bradford, R. Paradise Lost. Open University Press: Philadelphia, 1992.

- Butler, George F., "Giants and Fallen Angels in Dante and Milton: The Commedia and the Gigantomachy in Paradise Lost, Modern Philology, Vol. 95, No. 3 (Feb., 1998), pp. 352-363.

- Carey, John and Fowler, Alastair. The Poems of John Milton. London, 1971.

- Empson, William. Milton's God Rev. ed. London, 1965.

- Eliot, T.S. "Milton" and "A Note on the Verse of John Milton." On Poetry and Poets. London, 1957.

- Frye, Northrop. The Return of Eden: Five Essays on Milton's Epics. Toronto, 1965.

- Kermode, Frank, ed. The Living Milton: Essays by Various Hands. London, 1960.

- Lewis, C.S. A Preface to Paradise Lost. London, 1942.

- Rajan, Balachandra. Paradise Lost and the Seventeenth Century Reader. London, 1947.

- Ricks, Christopher. Milton's Grand Style. Oxford, 1963.

- Miller, Timothy C. (Ed.) The Critical Response to John Milton's "Paradise Lost" (Critical Responses in Arts & Letters) Greenwood Publishing Group. Westport, 1997.

External links

Online text

- Paradise Lost at Dartmouth's Milton Reading Room

Other information

- Norton Anthology of English Literature – Paradise Lost in Context – includes historical context, iconography, topical explorations and web resources

- "Free-Will Theodicy, Middle-Knowledge Theology, Ramist Linguistics, and Satanic Psychology in Paradise Lost" (pdf) by Horace Jeffery Hodges.

- Satan Deconstructed In Paradise Lost

- "Free will and necessity in Milton's Paradise Lost" by Gilbert McInnis.

- Selected bibliography at the Milton Reading Room – includes background, biography, criticism

- Paradise Lost Study Guide