Man: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

Tawkerbot4 (talk | contribs) m BOT - rv 66.159.178.166 (talk) to last version by Bogdangiusca |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{otheruses1|[[human]] [[male]]s}}'' For the history and usage of the word "man", see [[man (word)]]'' |

|||

in life, are: |

|||

[[Image:Male.svg|left|30px]] |

|||

A '''man''' is a [[male]] [[human]]. <!--The word adult is not needed in this sentence; see the following sentence.--> The term ''male'' (irregular plural: ''men'') is usually used for an adult, with the term [[boy]] being the usual term for a male child or adolescent (sometimes also applied to adult men). However, the term is also used for a male human regardless of age, sometimes even extended to more primitive [[humanoids]] than the present species ''Homo sapiens sapiens'', as in [[apeman]]. |

|||

[[Image:Vitruvian-cropped.jpg|thumb|Leonardo da Vinci's ''[[Vitruvian Man]]'' is generally considered to be one of the finest artistic studies of man's proportions.]] |

|||

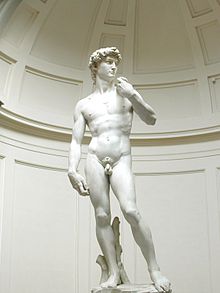

[[Image:Michelangelos David.jpg|thumb|[[Michelangelo's David]] is widely considered to be one of the finest artistic portrayals of a man.]] |

|||

==Age and terminology== |

|||

[[Manhood]] is the period in a male's life after he has transitioned from boyhood, at least physically, during [[puberty]]. Many cultures have [[rite of passage|rites of passage]] to symbolize a man's [[coming of age]], such as [[Confirmation (sacrament)|confirmation]] in some branches of [[Christianity]], [[B'nai Mitzvah|bar mitzvah]] in [[Judaism]], or even just the celebration of the eighteenth or twenty-first [[birthday]]. |

|||

A [[boy]] is a [[male]] [[human]] [[child]]. For many, the word ''man'' implies a certain degree of maturity and responsibility that young men in particular often feel unprepared for; yet they may also feel too old to be called a ''boy''. For this reason, many avoid using either ''man'' or ''boy'' to describe a young man and prefer colloquial terms such as ''bloke'', ''lad'', ''chap'', ''fellow'', ''guy'' or ''dude''. |

|||

== Biology and gender == <!-- Please don't rename to "...sex" as there is a link from "woman" here. Biology and sex is redundant here, whereas this section does discuss gender in paragraph 5 --> |

|||

[[Image:Gloeden1895.jpg|framed|left|Photograph of a [[nudity|nude]] man by [[Wilhelm von Gloeden]], ca. 1895.]] |

|||

{{main|Secondary sexual characteristics}} |

|||

Humans exhibit sexual [[dimorphism]] in many characteristics, many of which have no direct link to reproductive ability, however most of these characteristic do have a role in sexual attraction. Most expressions of sexual dimorphism in humans are found in height, weight, and body structure, though there are always examples that do not follow the overall pattern. For example, men tend to be taller than [[women]], but there are many people of both sexes who are in the mid-height range for the species. |

|||

Some examples of male secondary sexual characteristics in humans, those acquired as boys become men or even later in life, are: |

|||

* deeper voice |

* deeper voice |

||

* taller height |

* taller height |

||

Revision as of 00:06, 5 December 2006

For the history and usage of the word "man", see man (word)

A man is a male human. The term male (irregular plural: men) is usually used for an adult, with the term boy being the usual term for a male child or adolescent (sometimes also applied to adult men). However, the term is also used for a male human regardless of age, sometimes even extended to more primitive humanoids than the present species Homo sapiens sapiens, as in apeman.

Age and terminology

Manhood is the period in a male's life after he has transitioned from boyhood, at least physically, during puberty. Many cultures have rites of passage to symbolize a man's coming of age, such as confirmation in some branches of Christianity, bar mitzvah in Judaism, or even just the celebration of the eighteenth or twenty-first birthday.

A boy is a male human child. For many, the word man implies a certain degree of maturity and responsibility that young men in particular often feel unprepared for; yet they may also feel too old to be called a boy. For this reason, many avoid using either man or boy to describe a young man and prefer colloquial terms such as bloke, lad, chap, fellow, guy or dude.

Biology and gender

Humans exhibit sexual dimorphism in many characteristics, many of which have no direct link to reproductive ability, however most of these characteristic do have a role in sexual attraction. Most expressions of sexual dimorphism in humans are found in height, weight, and body structure, though there are always examples that do not follow the overall pattern. For example, men tend to be taller than women, but there are many people of both sexes who are in the mid-height range for the species.

Some examples of male secondary sexual characteristics in humans, those acquired as boys become men or even later in life, are:

- deeper voice

- taller height

- facial hair or beard

- diamond shape pubic hair pattern

- increased body size overall

- less subcutaneous fat

- increase in overall body hair

- male pattern baldness

- coarser skin

- darker skin tone

- A higher level of androgenic hormones such as testosterone, making it easier for most men than most women to develop their muscles.

The sex organs of a man are part of the reproductive system, consisting of the penis, testicles, vas deferens, and the prostate gland. The male reproductive system's function is to produce semen which carries sperm and thus genetic information that can unite with an egg within a woman. Since sperm that enters a woman's uterus and then fallopian tubes goes on to fertilize an egg which develops into a fetus or child, the male reproductive system plays no necessary role during the gestation. The concept of fatherhood and family exists in human societies. The study of male reproduction and associated organs is called andrology. Most, but not all, men have the karyotype 46/XY.

In general, men suffer from many of the same illnesses as women. However, there are some sex-related illnesses that occur only, or more frequently, in men. For example, autism and color blindness are more common in men than women. As well, some age-related disorders such as Alzheimer's disease appear to be more common among men, though whether this is due to a genuinely higher incidence or because men have lower life expectancies than women is uncertain.

Biological factors are usually not the sole determinants of whether a person considers themselves a man or is considered a man. For example, individuals who are assigned a male gender at birth can have atypical male physiology for hormonal or genetic reasons (see intersex), or can be psychologically a woman (see transgender), and some of those intersex or transgendered people seek sex reassignment as a woman later in their lives. In the other direction, people assigned a female gender at birth based on visible characteristics, who may be either intersexed or biologically indistinguishable from a woman, sometimes seek sex reassignement as a man. (see transgender, transsexual, see also gender identity, gender role and transman).

Additionally, 20% of males, particularly in the U.S., the Philippines, and South Korea, as well as Jews and Muslims from all countries, have experienced circumcision, a process of altering the penis from its natural state by removing the foreskin.

Gender stereotypes

Enormous debate in Western societies has focused on perceived social, intellectual, or emotional differences between men and women. These differences are very difficult to quantify for both scientific and political reasons. Below are a few stereotypical claims sometimes made about men in relation to women:

- More aggressive than women.

- More competitive

- Less empathy and awareness of social nuance than women.

- More self-confident (even arrogant) and thus better leaders than women.

- Less emotional than women.

- More technically skilled than women.

- More focused, but less able to attend to several things at once, than women.

Some of these differences have been supported by scientific research; others have not. For example, in interpersonal relationships, most research has found that men and women are equally aggressive.[citation needed] Men do tend to be more aggressive outside of the home.[citation needed] It is especially difficult and contentious for science to separate the "innate" or biological differences from the learned or social differences. All should be considered broad generalizations; that is, at least a large minority of either gender would fit better with the other gender in any one of these aspects.

A number of the above stereotypes were not perceived in the same way as today (i.e., their applications to particular aspects and spheres of life, such as work vs. home) until the 19th century, beginning with industrialization.

In terms of outward appearance, few men in Western cultures wear cosmetics or clothing generally associated with female gender roles. (Doing so is generally stigmatized and viewed as cross-dressing.)

Culture and gender roles

Well into prehistoric culture, men are believed to have assumed a variety of social and cultural roles which are likely similar across many groups of humans. In hunter-gatherer societies, men were often if not exclusively responsible for all large game killed, the capture and raising of most or all domesticated animals, the building of permanent shelters, the defense of villages, and other tasks where the male physique and strong spatial-cognition were most useful. Some anthropologists believe that it may have been men who led the Neolithic Revolution and became the first pre-historical ranchers, as a possible result of their intimate knowledge of animal life.

Throughout history, the roles of men have changed greatly. As societies have moved away from agriculture as a primary source of jobs, the emphasis on male physical ability has waned. Traditional gender roles for middle-class men typically involved jobs emphasizing moderate to hard manual labor (see Blue-collar worker), often with no hope for increase in wage or position. For poorer men among the working classes the need to support their families, especially during periods of industrial change and economic decline, forced them to stay in dangerous jobs working long arduous hours, often without retirement. Many industrialized countries have seen a shift to jobs which are less physically demanding, with a general reduction in the percentage of manual labor needed in the work force (see White-collar worker). The male goal in these circumstances is often of pursuing a quality education and securing a dependable, often office-environment, source of income.

The Men's Movement is in part a struggle for the recognition of equality of opportunity with women, and for equal rights irrespective of gender, even if special relations and conditions are willingly incurred under the form of partnership involved in marriage. The difficulties of obtaining this recognition are due to the habits and customs recent history has produced. Through a combination of economic changes and the efforts of the feminist movement in recent decades, men in some societies now face women who receive educational and workplace benefit based solely on gender. Modern men in Western society still face challenges in the workplace as well as on the topics of education, violence, health care, politics, and fatherhood - to name a few. Research has identified anti-male sexism, and the effects of its expansion may increase hardships for many males.[citation needed]

Gallery

-

A Tasmanian Aborigine man

-

A man from Cameroon

-

An indigenous man from Mexico

-

A man from the United States playing tennis in a wheelchair

-

Two indigenous men from Brazil

-

An Indian man (Rabindranath Tagore)

-

An Iraqi militiaman

-

A Native American man meditating

-

A U.S. Marine running through water

-

A young Bedouin man

References

Further reading

- Andrew Perchuk, Simon Watney, Bell Hooks, The Masculine Masquerade: Masculinity and Representation, MIT Press 1995

- Pierre Bourdieu, Masculine Domination, Paperback Edition, Stanford University Press 2001

- Robert W. Connell, Masculinities, Cambridge : Polity Press, 1995

- Warren Farrell, Myth of Male Power Berkley Trade, 1993 ISBN 0-425-18144-8

- Michael Kimmel (ed.), Robert W. Connell (ed.), Jeff Hearn (ed.), Handbook of Studies on Men and Masculinities, Sage Publications 2004