History of Monopoly: Difference between revisions

m Reverted vandalism by 200.43.196.131 to version 93957428 by Casper2k3 |

Richman271 (talk | contribs) m Removed pic from article until revert |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{featured article}} |

{{featured article}} |

||

:<span class="dablink">''"History of Monopoly" redirects here. For information about the historical practice of establishing dominance in an industry, see [[Monopoly#Historical examples of alleged de facto monopolies|monopoly]].''</span><noinclude> |

:<span class="dablink">''"History of Monopoly" redirects here. For information about the historical practice of establishing dominance in an industry, see [[Monopoly#Historical examples of alleged de facto monopolies|monopoly]].''</span><noinclude> |

||

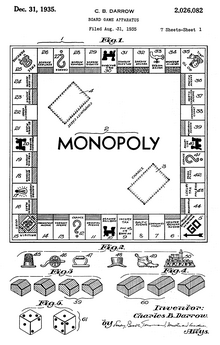

[[Image:Historic U.S. Monopoly game boards.png|thumb|right|The five sets of the board game Monopoly depicted here show the evolution of the game's artwork and designs in the United States from 1935–2005.]] |

|||

The '''history of the board game [[Monopoly (game)|Monopoly]]''' can be traced back to the early 1900s. Based on original designs by [[Elizabeth Magie]], several board games were developed from 1903 through the 1930s that involved the buying and selling of land and the development of that land. By 1934, a board game was created much like the version of Monopoly sold by [[Parker Brothers]] and its parent companies through the rest of the 20th century, and into the 21st. Several different people, mostly in the Midwestern United States and near the U.S. East Coast, contributed to the game's design and evolution. |

The '''history of the board game [[Monopoly (game)|Monopoly]]''' can be traced back to the early 1900s. Based on original designs by [[Elizabeth Magie]], several board games were developed from 1903 through the 1930s that involved the buying and selling of land and the development of that land. By 1934, a board game was created much like the version of Monopoly sold by [[Parker Brothers]] and its parent companies through the rest of the 20th century, and into the 21st. Several different people, mostly in the Midwestern United States and near the U.S. East Coast, contributed to the game's design and evolution. |

||

Revision as of 01:59, 13 December 2006

- "History of Monopoly" redirects here. For information about the historical practice of establishing dominance in an industry, see monopoly.

The history of the board game Monopoly can be traced back to the early 1900s. Based on original designs by Elizabeth Magie, several board games were developed from 1903 through the 1930s that involved the buying and selling of land and the development of that land. By 1934, a board game was created much like the version of Monopoly sold by Parker Brothers and its parent companies through the rest of the 20th century, and into the 21st. Several different people, mostly in the Midwestern United States and near the U.S. East Coast, contributed to the game's design and evolution.

By the 1970s, the idea that the game had been created solely by Charles Darrow had become popular folklore, printed in the game's instructions, and even the 1974 book The Monopoly Book: Strategy and Tactics of the World's Most Popular Game by Maxine Brady. That same decade, Professor Ralph Anspach fought Parker Brothers and its then parent company, General Mills, over the trademarks of the Monopoly board game. Through the research of Anspach, and others, much of the early history of the game was "rediscovered." Anspach even confronted Brady over the actual history of the game on Barry Farber's New York City talk show in 1975.[1] Because of the lengthy court process, and appeals, the legal status of Parker Brothers' trademarks on the game was not settled until 1985. The game's name remains a registered trademark of Parker Brothers, as does its specific design elements. At the conclusion of the court case, the game's logo and graphic design elements became part of a larger Monopoly brand, licensed by Parker Brothers' parent companies onto a variety of items through the present day. Despite the "rediscovery" of the board game's early history in the 1970s and 1980s, and several books and journal articles on the subject, Hasbro (Parker Brothers' current parent company) does not acknowledge any of the game's history before Charles Darrow on their official Monopoly website.[2]

International tournaments, first held in the early 1970s, continue to the present day, with the next world championship scheduled for 2008. Starting in 1985, a new generation of spin-off board games and card games appeared on both sides of the Atlantic Ocean. In 1989, the first of many video game and computer game editions was published. Since 1994, many official variants of the game, based on cities other than Atlantic City, New Jersey (the official U.S. setting) or London (the official Commonwealth setting), have been published by Hasbro or its licensees. Other cities, territories, states and countries, and licensed properties have also become variants and editions of Monopoly.

Game development 1903–1934

In 1903, a Georgist, Lizzie Magie, applied for a patent on a game called The Landlord's Game with the object of showing how rents enrich property owners and impoverish tenants. She knew that some people could find it hard to understand why this happened and what might be done about it, and she thought that if the rent problem and the Georgist solution to it were put into the concrete form of a game, it might be easier to demonstrate. She was granted the patent for the game in January 1904. The Landlord's Game became one of the first to use a "continuous path," without clearly defined start and end spaces on its board.[3] A copy of Magie's game, dating to 1903/1904, was discovered for the PBS series "History's Detectives." This copy featured property groups, organized by letters, later a major feature of Monopoly as published by Parker Brothers.[4]

Although The Landlord's Game was patented, and some hand-made boards were made, it was not actually manufactured and published until 1906. Magie and two other Georgists established the Economic Game Company of New York, which began publishing her game.[5] Magie submitted an edition published by the Economic Game Company to Parker Brothers around 1910, which George Parker declined to publish.[5]In the UK it was published in 1913 by the Newbie Game Company under the title Brer Fox an' Brer Rabbit.[6][7] Shortly after the game's formal publication, Scott Nearing, a professor in the Wharton School of Finance at the University of Pennsylvania, began using the game as a teaching tool in his classes. His students made their own boards, and taught the game to others.[8] After Nearing was dismissed from the Wharton School, he began teaching at the University of Toledo. A former student of Nearing's, Rexford Guy Tugwell, also taught The Landlord's Game at Wharton, and took it with him to Columbia University.[9]

A shortened version of Magie's game, which eliminated the second round of play that used a Georgist concept of a single Land value tax, had become common during the 1910s, and this variation on the game became known as "Auction Monopoly."[10] Magie moved back to Illinois, was married and moved to the Washington, D.C. area with her husband by 1923, and re-patented a revised version of The Landlord's Game in 1924 (under her married name, Elizabeth Magie Phillips). This version, unlike her first patent drawing, included named streets (though the versions published in 1910 based on her first patent also had named streets). Magie's first patent had expired, and she sought to regain control over the plethora of hand-made games.[11] For her 1924 edition a couple of streets on the board were named after Chicago streets and locations, notably "The Loop" and "Lake Shore Drive."[12] This revision included a special "Monopoly" rule and card that allowed higher rents to be charged when all three railroads and utilities were owned, and included "chips" to indicate improvements on properties.[13] Magie again approached Parker Brothers about her game, and George Parker again declined.[14] Apart from commercial distribution, it spread by word of mouth and was played in slightly variant homemade versions over the years by Quakers, Georgists, university students (including students at Smith College, Princeton and MIT), and others who became aware of it.[15][16]

In the 1920s, the game became popular around the community of Reading, Pennsylvania. Another former student of Scott Nearing, Thomas Wilson, taught the game to two brothers, Louis and Ferdinand Thun.[17] After the Thuns learned the game and began teaching its rules to their fraternity brothers at Williams College. Daniel W. Layman, in turn, learned the game from the Thun brothers (who later tried to sell copies of the game commercially, but were advised by an attorney that the game could not be patented, as they were not its inventors).[18] Layman later returned to his hometown of Indianapolis, Indiana, and produced a version of the board based on streets of that city. This he sold under the name The Fascinating Game of Finance (later shortened to Finance), beginning in 1932.[19] Layman first produced and sold the game with a friend in Indianapolis, who owned a company called Electronic Laboratories.[20] Layman soon sold his rights to the game, which was then licensed, produced and marketed by Knapp Electric.[21] The published board featured four railroads, one per side, Chance and Community Chest cards and spaces, and properties grouped by symbol, rather than color.[22]

It was in Indianapolis that Ruth Hoskins learned the game, and took it back to Atlantic City.[23] After she arrived, Hoskins made a new board with Atlantic City street names, and taught it to a group of local Quakers.[24] It has been argued that their greatest contribution to the game was to reinstate the original Lizzie Magie rule of "buying properties at their listed price" rather than auctioning them, as the Quakers did not believe in auctions.[25][26] The Atlantic City board was the one taught to Charles Todd, who in turn taught Esther Darrow, wife of Charles Darrow.[27] Todd had shortened the name Shore Fast Line to Short Line, and also introduced the infamous "Marvin Gardens" misspelling, both of which Darrow reproduced.[28] After learning the Monopoly game, Darrow then began to distribute the game himself.[18] Darrow initially made the sets of the Monopoly game by hand with the help of his first son, William Darrow, and his wife. Their new sets inadvertently kept Charles Todd's misspelling of "Marven Gardens" as "Marvin Gardens," which continues to this day.[27] Charles Darrow drew the designs with a drafting pen on round pieces of oilcloth, and then his son and his wife helped fill in the spaces with colors and make the title deed cards and the Chance cards and Community Chest cards. After the demand for the game increased, Darrow contacted a printing company, Patterson and White, which printed the designs of the property spaces on square carton boards. Darrow's game board's designs included elements later made famous in the version eventually produced by Parker Brothers, including black locomotives on the railroad spaces, the car on "Free Parking," the red arrow for "Go," the faucet on "Water Works" and the lightbulb on "Electric Company" and the question marks on the "Chance" spaces, though many of the actual icons were created by a hired graphic artist.[29][30] While Darrow received a copyright on his game in 1933, its specimens have disappeared from the files of the United States Copyright Office, though proof of its registration remains.[31]

Acquisition by Parker Brothers

Darrow first took the game to Milton Bradley and attempted to sell it as his personal invention. They rejected it in a letter dated May 31, 1934.[32] After Darrow first sent the game Parker Brothers later in 1934, they rejected the game as "too complicated, too technical, [and it] took too long to play."[33] Darrow was told that his game had "fifty-two fundamental playing errors," to deliberately discourage him.[33] Darrow received a rejection letter from the firm dated October 19, 1934.[32] By 1935, however, the company heard about the game's excellent sales in Philadelphia, and scheduled a new meeting with Darrow in New York City. There they bought Darrow's game, helped him take out a patent on it, and purchased his remaining inventory.[34] Parker Brothers subsequently decided to buy out Magie's 1924 patent and the copyrights of other commercial variants of the game in order to claim that it had legitimate undisputed rights to the game — a monopoly, in fact.

Robert Barton, president of Parker Brothers, bought the rights to Finance from Knapp Electric in 1935. Finance would be redeveloped, updated, and continued to be sold by Parker Brothers into the 1970s.[35] Rights to other games based on a similar principle, such as a game called Inflation, published by Rudy Copeland in Texas, also came to the attention of Parker Brothers management in the 1930s, after they began sales of Monopoly.[36] Copeland continued sales of the latter game after Parker Brothers attempted a patent lawsuit against him. Parker Brothers held the Magie and Darrow patents, but settled with Copeland rather than going to trial, since Copeland was prepared to have witnesses testify that they had played "monopoly" before Darrow's "invention" of the game.[37] The court settlement allowed Copeland to license Parker Brother's patents.[38] Other agreements were reached on Big Business by Transogram, and Easy Money by Milton Bradley, based on Daniel Layman's Finance.[39] Another clone, called Fortune, was sold by Parker Brothers, and became combined with Finance in some editions.[40]

Monopoly was first marketed on a broad scale by Parker Brothers in 1935. A Standard Edition, with a small black box and separate board, and a larger Deluxe Edition with a box large enough to hold the board, were sold in the first year of Parker Brothers' ownership. These were based on the two editions sold by Darrow.[41] George Parker himself rewrote many of the game's rules, insisting that "short game" and "time limit" rules be included.[42] On the original Parker Brothers board (reprinted in 2002 by Winning Moves Games), there were no icons for the Community Chest spaces (the blue chest overflowing with gold coins came later) and no gold ring on the Luxury Tax space. Nor were there property values printed on spaces on the board. The Income Tax was slightly higher (being US$300 or 10%, instead of the later US$200 or 10%). Some of the designs known today were implemented at the behest of George Parker.[42] The Chance cards and Community Chest cards were illustrated (though some prior editions consisted solely of text), but were without "Rich Uncle Pennybags," who was introduced in 1936.

Late in 1935, after learning of The Landlord's Game and Finance, Robert Barton held a second meeting with Charles Darrow in Boston. Darrow admitted that he had copied the game from a friend's set, and he and Barton reached a revised royalty agreement, granting Parker Brothers worldwide rights and releasing Darrow from legal costs that would be incurred in defending the origin of the game.[43]

Licensing outside the United States

In December 1935, Parker Brothers sent a copy of the game to Victor Watson Sr. of Waddington Games. Watson and his son Norman tried the game, and liked it so much that Waddingtons and Parker Brothers held their first transatlantic "trunk call" after the Watsons had spent a weekend play-testing the game. Waddingtons was granted licensing rights for Europe and the British Commonwealth, excluding Canada.[44] Waddingtons version, their first board game, with locations from London substituted for the original Atlantic City ones, was first produced in 1936. The game was very successful in the United Kingdom and France, but was denounced in Nazi Germany.[45] A new German edition would not appear until the 1960s.[46] Waddingtons licensed other editions from 1936-38, and the game was exported from the UK and resold or reprinted in Switzerland, Belgium, Australia, Chile, Italy, The Netherlands and Sweden. In Italy, under the fascists, the game was changed dramatically so that it would have an Italian name, locations in Milan, and changes in the rules. Italian publishers Editrice Giochi still produce the game in Italy, holding a special and mostly independent relationship from Hasbro.[47]

In Austria, versions of the game first appeared as Business and Spekulation (Speculation), and eventually evolved to become Das Kaufmännische Talent (DKT) (The Businessman's Talent). Versions of DKT have been sold in Austria since 1940. The game first appeared as Monopoly in Austria in about 1981.[48] The Waddingtons edition was imported into The Netherlands starting in 1937, and a fully translated edition first appeared in 1941.[49] Waddingtons later produced special games during World War II, distributed by the International Committee of the Red Cross, which secretly contained files, a compass, a map printed on silk, and real currency hidden amongst the Monopoly money, to enable prisoners of war to escape from German camps.[50][51] Collector Albert C. Veldhuis features a map on his "Monopoly Lexicon" website showing which versions of the game were remade and distributed in other countries, with the Atlantic City, London and Paris versions being the most influential.[52]

Marketing within the United States 1930s

In 1936 Parker Brothers published four further editions along with the original two: the Popular Edition, Fine Edition, Gold Edition, and Deluxe Edition, with prices ranging from US$2 to US$25 in 1930s money.[53] After Parker Brothers began to release its first editions of the game, Elizabeth Magie Phillips was profiled in the Washington D.C. Evening Star newspaper, which discussed her two editions of "The Landlord's Game."[54] In December 1936, wary of the Mah-Jongg and Ping-Pong fads that had left unsold inventory stuck in Parker Brothers' warehouse, George Parker ordered a stop to Monopoly production as sales leveled off. However, during the Christmas season, sales picked up again, and continued a resurgence.[55] In early 1937, as Parker Brothers was preparing to release the board game "Bulls and Bears" with Darrow's photograph on the box lid (though he had no involvement with the game), a Time magazine article about the game made it seem as if Darrow was the sole inventor of both "Bulls and Bears" and Monopoly.

If it is true that the devil finds work for idle hands to do, the No. 1 U.S. Mephistopheles is currently a mild little Philadelphian named Charles Darrow. Mr. Darrow's claim to the title, based on Monopoly, U.S. parlor craze of 1936, was last week reinforced when Parker Brothers began to distribute his second invention for idle hands. The new Darrow game is Bulls & Bears. Success of Monopoly, which was last week estimated to be in its sixth million and selling faster than ever, gave Bulls & Bears a pre-publication sale of 100,000, largest on record for a new game.

— Time, "Sport: 1937 Games," 1 February 1937, Page 44

Parker Brothers marketing 1940s–1970s

At the start of World War II, both Parker Brothers and Waddingtons stockpiled materials they could use for further game production. During the war, Monopoly was produced with wooden tokens in the U.S., and the game's cellophane cover was eliminated.[56] In the UK, metal tokens were also eliminated, and a special spinner was introduced to take the place of dice. The game even remained in print for a time in the Netherlands, as the printer there was able to maintain a supply of paper.[57] The game remained popular during the war, particularly in camps, and soldiers playing the game became part of the product's advertising in 1944.[58]

After the war, the game's sales went from 800,000 a year to over a million. The French and German editions re-entered production, and new editions for Spain, Greece, Finland and Israel were first produced.[59] By the late 1950s, the company printed only game sets with board, pieces and materials housed in a single white box.[60] Several copies of this edition were exhibited at the American National Exhibition in Moscow in 1959. All of them were stolen from the exhibit.[61] In the early 1960s, "Monopoly happenings" began to occur, mostly marathon game sessions, which were recognized by a Monopoly Marathon Records Documentation Committee in New York City.[62] In addition to marathon sessions, games were played on large indoor and outdoor boards, within backyard pits, on the ceiling in a University of Michigan dormitory room, and underwater.[63] In 1965, a 30th anniversary set was produced in a special plastic case.[64] By 1974, Parker Brothers had sold 80 million sets of the game.[65] In 1973, as the Atlantic City Commissioner of Public Works considered name changes for Baltic and Mediterranean Avenues, fans of the board game, with support from the then-President of Parker Brothers, successfully lobbied for the city to keep the names.[66] In 1975, another anniversary edition was produced, but this edition came in a cardboard box looking much like a standard edition.[64]

Further evolution of game play

The official Parker Brothers rules have remained largely unchanged since 1936. Ralph Anspach argued against this during his conversation with Maxine Brady in 1975, calling it an end to "steady progress" and an impediment to progress.[67] Several authors who have written about the board game have noted many of the "house rules" that have become common among players, although they do not appear in Parker Brothers' rules sheets. Gyles Brandreth included a section titled "Monopoly Variations," Tim Moore notes several such rules used in his household in his Foreword, Phil Orbanes included his own section of variations, and Maxine Brady noted a few in her preface.[68][69][70][71] When creating some of the modern licensed editions, such as the Looney Tunes and The Powerpuff Girls editions of Monopoly, Hasbro included special variant rules to be played in the theme of the licensed property. Infogrames, which has published a CD-ROM edition of Monopoly, also includes the selection of "house rules" as a possible variant of play. The first major changes to the Monopoly game itself occurred with the publication of both the Monopoly Here & Now Electronic Banking Edition by Hasbro and Monopoly: The Mega Edition by Winning Moves Games in 2006. The Electronic Banking Edition uses Visa-branded debit cards and a debit card reader for monetary transactions, instead of paper bills.[72] This edition is available in the UK, Germany, France and Australia. The Mega Edition has been expanded to include fifty-two spaces (with more street names taken from Atlantic City), skyscrapers (to be played after hotels), train depots, the 1000 denomination of play money, as well as "bus tickets" and a speed die.[73]

The Monopoly Tournaments 1973–2004

The first Monopoly Tournaments were suggested by Victor Watson of Waddingtons after the 1972 World Chess Championship. Such championships are also held for players of the board game Scrabble. Victor Watson and Parker Brothers' Randolph "Ranny" Barton began holding tournaments in the UK and United States respectively. World Champions were declared in the United States in 1973 and 1974 (and are still considered official World Champions by Hasbro). While the 1973 tournament, the first, matched three United States regional champions against the UK champion, and thus could be argued as the first international tournament, true multinational international tournaments were first held in 1975.[74] That year, to mark the 40th anniversary of Parker Brothers production of the game, a European tournament was held in Reykjavík, Iceland, the same site as the 1972 World Chess Championship. Accounts differ as to the eventual winner: Philip Orbanes names John Mair, representing Ireland and the eventual World Monopoly Champion of 1975, as also having won the European Championship.[75] Gyles Brandreth, himself a later European Monopoly Champion, names Pierre Milet, representing France, as the European Champion.[76] Both authors do agree on John Mair as being the first true World Champion, as decided in tournament play held in Washington, D.C. days after the conclusion of the European Championship, in November 1975.

By 1982, tournaments in the United States featured a competition between tournament winners in all fifty states, competing to become the United States Champion. National tournaments are held in the United States and United Kingdom the year before World Championships. The determination of the United States Champion was changed for the 2003 tournament: winners of an Internet-based quiz challenge were selected to compete, rather than one state champion for each of the fifty states.[77] The tournaments are now held every four years, with the next World Championship scheduled for 2008. The U.S. edition Monopoly board is used at the World Championship level, while national variants are used at the national level.[78] Interestingly, since true international play began in 1975, no World Champion has come from the United States, still considered the board game's "birthplace."

World Tournament locations and champions

| Year | Location | Winner |

| 1973 | Washington, D.C. | Lee Bayrd, United States [79] |

| 1974 | Washington, D.C. | Alvin Aldridge, United States [79] |

| 1975 | Washington, D.C. | John Mair, Ireland [79] |

| 1977 | Monte Carlo, Monaco | Cheng Seng Kwa, Singapore [79] |

| 1980 | Bermuda | Cesare Bernabei, Italy [79] |

| 1983 | Palm Beach, Florida | Greg Jacobs, Australia [79] |

| 1985 | Atlantic City, New Jersey | Jason Bunn, United Kingdom [79] |

| 1988 | London, England | Ikuo Hyakuta, Japan [79] |

| 1992 | Berlin, Germany | Joost van Orden, The Netherlands [79] |

| 1995 | Monte Carlo, Monaco | Christopher Woo, Hong Kong [79] |

| 2000 | Toronto, Ontario, Canada | Yutaka Okada, Japan [80] |

| 2004 | Tokyo, Japan (originally scheduled for Hong Kong)[81] | Antonio Zafra Fernandez, Spain[82] |

Anti-Monopoly, Inc. vs. General Mills Fun Group, Inc. court case 1976–1985

In the mid-1970s, Parker Brothers and its then corporate parent, General Mills, attempted to suppress publication of a game called Anti-Monopoly, designed by San Francisco State University economics professor Ralph Anspach. Anspach began to research the game's history, and argued that the copyrights and trademarks held by Parker Brothers should be nullified, as the game came out of the public domain. Among other things, Anspach discovered the empty 1933 Charles B. Darrow file at the United States Copyright Office, testimony from the Inflation game case that was settled out of court, and letters from Knapp Electric challenging Parker Brothers over Monopoly. As the case went to trial in November, 1976, Anspach produced testimony by many involved with the early development of the game, including Catherine and William Allphin, Dorothea Raiford and Charles Todd. William Allphin attempted to sell a version of the game to Milton Bradley in 1931, and published an article about the game's early history in the UK in 1975.[83] Raiford had helped Ruth Hoskins produce the early Atlantic City games.[84] Even Daniel Layman was interviewed, and Darrow's widow was deposed.[85] The presiding judge, Spencer Williams, originally ruled for Parker Brothers/General Mills in 1977, allowing the Monopoly trademark to stand, and allowing the companies to destroy copies of Anspach's Anti-Monopoly.[86] Anspach appealed.

In 1979, the 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals ruled in favor of Professor Anspach, which agreed with the facts about the game's history which differed from Parker Brothers' "official" account. The court also upheld a "purchasing motivation" test, nullifying the Monopoly trademark, and returned the case to Judge Williams. Williams heard the case again in 1980, and in 1981 he upheld his first decision.[87] Anspach appealed again, and in November 1981, the appeals court again upheld their own decision.[88] The case was then appealed by General Mills/Parker Brothers to the United States Supreme Court, which decided not to hear the case in February 1983, and denied a Petition for Rehearing in April.[89] The Supreme Court allowed the appeals court's decision to stand and further allowed Anspach to resume publication of his game.[90]

With the trademark nullified, Parker Brothers and other firms lobbied the United States Congress and got a revision of the trademark laws. The case was finally settled in 1985, with Monopoly remaining a valid trademark of Parker Brothers, and Anspach assigning the Anti-Monopoly trademark to them but retaining the ability to use it under license.[91] Anspach received compensation for court costs and the destroyed copies of his game, as well as unspecified damages. He was allowed to resume publication with a legal disclaimer.[92] Anspach later published a book about his research and legal fights with General Mills, Kenner Parker Toys and Hasbro.

Localizations, licenses and spin-offs

The original Monopoly game had been localized for the cities or areas in which it was played and Parker Brothers has continued this practice. Their version of Monopoly has been produced for international markets, with the place names being localized for cities including London and Paris and for countries including the Netherlands and Germany, among others. By 1982, Parker Brothers stated that the game "has been translated into over 15 languages...."[93] As of 2006, counts of the languages that Monopoly has been translated for are estimated between 25 and 30.

The game has also inspired official spin-offs, such as Advance to Boardwalk (1985), the card game Free Parking (1988), the dice game Don't Go To Jail (1991), two generations of card games (Express Monopoly (1993) and Monopoly: The Card Game (1999)), and a second product line in Monopoly Junior, first published in 1990. In the late 1980s, official editions of Monopoly appeared for the Sega Master System and the Commodore 64 and Commodore 128.[94] A television game show, produced by King World Productions, was attempted in the summer of 1990, but only lasted for 12 episodes. In 1991–1992, official versions appeared for the Apple Macintosh and Nintendo's NES, SNES and Game Boy.[95] In 1995, as Hasbro (which had taken over Tonka Kenner Parker in the early 1990s) was preparing to launch Hasbro Interactive as a new brand, they chose Monopoly to be their first CD-ROM game, with an option for playing over the Internet. Monopoly CD-ROM versions of the officially licensed Star Wars and FIFA World Cup '98 editions were also released.[96] Later CD-ROM exclusive spin-offs, Monopoly Casino and Monopoly Tycoon, were also produced under license.

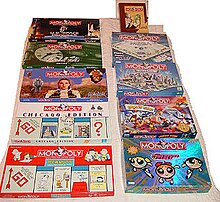

Since 1994, different manufacturers of the game have created dozens of versions in which the names of the properties and other elements of the game are replaced by others with some theme. There are officially licensed versions about national parks, Star Trek, Star Wars, Disney, various particular cities (such as Las Vegas or Cambridge), states, colleges and universities, the Football World Cup, NASCAR, and many others. Hasbro has officially licensed two companies to produce further Monopoly editions: USAopoly and Winning Moves Games. Unofficial versions of the game, which share some of the same playing features, but also feature many changes so as to not infringe on copyright, have been created by firms such as Late for the Sky Production Company and Help on Board. These are done for smaller cities, sometimes as charity fundraisers, and some have been created for college and university campuses, while some have non-geographical themes, such as Wine-opoly and Chocolate-opoly.

In late 1998, Hasbro announced a campaign to add an all-new token to U.S. standard edition sets of Monopoly. Voters were allowed to select from a biplane, a piggy bank, and a sack of money — with votes being tallied through a special website, via a toll-free phone number, and at F.A.O. Schwarz stores. In March 1999, Hasbro announced that the winner was the sack of money (with 51% of the vote, compared to 29% for the biplane and 20% for the piggy bank). Thus the sack of money became the first new token added to the game since the early 1950s.[97] In 1999, in a major marketing effort, Hasbro renamed the mascot Rich Uncle Pennybags to "Mr. Monopoly," felt by some to be a blander name.

Before the creation of Hasbro Interactive, and after its later sale to Infogrames, official computer and video game versions have been made available on many different platforms. In addition to the versions listed above, they have been produced for PC, Amiga, BBC Micro, Game Boy Color, Game Boy Advance, Sega Genesis, Nintendo 64, PlayStation, PlayStation 2, GameCube, Xbox, and mobile phones, as well as a handheld electronic game in 1997 and a Nintendo DS release (along with Boggle, Yahtzee and Battleship). In 2001, Stern Pinball, Inc. released a pinball machine version of Monopoly, designed by Pat Lawlor.[98]

Legal status

Although the game of Monopoly existed before the Parker Brothers edition, the company (now owned by Hasbro) has still claimed intellectual property rights over various aspects of the game, though it has not always prevailed in the courts.

The Anti-Monopoly case mentioned above, in addition to revealing some of the previously suppressed history of the game, also created a doctrine of "purchase motivation" a "test by which the trademark was valid only if consumers, when they asked for a Monopoly game, meant that they wanted Parker Brothers' version...."[99] As a result, the name "Monopoly" entered the public domain where the naming of games was concerned, and a profusion of non-Parker-Brothers variants were published. However, this doctrine was later eliminated by Congress in a revision of the trademark law,[99] and Parker Brothers/Hasbro now claims trademark rights to the name and its variants, and has asserted it against others such as the publishers of "Ghettopoly." Professor Anspach, as stated above, assigned the "Anti-Monopoly" trademark back to Parker Brothers, and Hasbro now owns it. Anspach's game remains in print, and is distributed and sold by University Games worldwide.[100][101][102]

Various patents have existed on the game of Monopoly and its predecessors such as "The Landlord's Game," but they are all now expired. The specific graphics of the game board, cards, and pieces are protected by copyright law and trademark law, as is the specific wording of the game's rules.

Monopoly as a brand

Parker Brothers created a few accessories and licensed a few products shortly after they began publishing the game in 1935. This included a money pad and the first Stock Exchange add-on in 1936, a birthday card, and a song by Charles Tobias (lyrics) and John Jacob Loeb (music).[103][104] At the conclusion of the Anti-Monopoly case, Kenner Parker Toys began to seek trademarks on the design elements of Monopoly. It was at this time that the game's main logo was redesigned to feature "Rich Uncle Pennybags" (now "Mr. Monopoly") reaching out from the second "O" in the word Monopoly.[105] All items stamped with the red MONOPOLY logo also feature the word 'Brand' in small print. In the mid-1980s, after the success of the first "collector's tin anniversary edition" (for the 50th anniversary) an edition of the game was produced by The Franklin Mint, the first edition to be published outside of Parker Brothers. At about the same time, McDonald's started its first Monopoly game promotions, considered their most successful, and which continue to the present day.[106]

In recent years the Monopoly brand has been licensed onto slot machines (which won an award in 1999), instant-win lottery tickets and lines of 1:64 scale model cars produced by Johnny Lightning which also included collectable game tokens.[107][108][109] The brand has also been licensed onto clothing and accessories, including a line of bathroom accessories.[110] The licenses to USAopoly and Winning Moves Games to produce new editions of the board game were also awarded in the mid-1990s.[111][112] While USAopoly produces many licensed spin-offs in North America, Winning Moves Games holds the licenses to produce different editions, including "city" editions, in the United Kingdom, France and Germany.[113][114][115]

See also

- Anti-Monopoly

- List of licensed Monopoly game boards

- Localized versions of the Monopoly game

- Monopoly (game show)

References

- ^ Anspach, Ralph (2000). The Billion Dollar Monopoly Swindle (Second edition ed.). Xlibris Corporation. pp. Pages 302-303. ISBN 0-7388-3139-5.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help) - ^ Hasbro.com page with their version of the history of Monopoly.

- ^ Orbanes, Philip E. (2006). Monopoly: The World's Most Famous Game & How it Got that Way. Da Capo Press. pp. Page 10. ISBN 0-306-81489-7.

- ^ Transcript of PBS History Detectives Episode 202.

- ^ a b Orbanes, Monopoly: The World's Most Famous Game, page 22.

- ^ Brer Fox an' Brer Rabbit photographs on tt.tf.

- ^ Orbanes, Monopoly: The World's Most Famous Game, page 23.

- ^ Orbanes, Monopoly: The World's Most Famous Game, pages 14-15.

- ^ Orbanes, Monopoly: The World's Most Famous Game, pages 24–25.

- ^ Ideafinder.com page on the history of Monopoly

- ^ Orbanes, Monopoly: The World's Most Famous Game, page 31.

- ^ Kennedy, Rod Jr. (2004). Monopoly: The Story Behind the World's Best-Selling Game (First edition ed.). Gibbs Smith. pp. Page 11. ISBN 1-58685-322-8.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Orbanes, Philip (1999). The Monopoly Companion: The Players Guide (Second edition ed.). Adams Media Corporation. pp. Page 16. ISBN 1-58062-175-9.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help) - ^ Orbanes, Monopoly: The World's Most Famous Game, page 33.

- ^ Orbanes, Monopoly Companion, Second edition. Page 17.

- ^ Orbanes, Monopoly: The World's Most Famous Game, page 30.

- ^ Orbanes, Monopoly: The World's Most Famous Game, page 41.

- ^ a b "From Berks to Boardwalk" originally published in the Winter 1978 "Historical Review of Berks County."

- ^ Kennedy. Page 12.

- ^ Orbanes, Monopoly: The World's Most Famous Game, page 45.

- ^ Orbanes, Monopoly: The World's Most Famous Game, page 46.

- ^ Passing Go: Early Monopoly, 1933–1937 by "Clarence B. Darwin" (pseudonym for David Sadowski), Folkopoly Press, River Forest, Illinois. Photograph on Page 197.

- ^ Walsh, Tim (2004). The Playmakers: Amazing Origins of Timeless Toys. Keys Publishing. pp. Page 48. ISBN 0-9646973-4-3.

- ^ Orbanes, Monopoly Companion Second edition. Page 20.

- ^ Anspach, The Billion Dollar Monopoly Swindle, page 140.

- ^ Orbanes, Monopoly: The World's Most Famous Game, page 52.

- ^ a b Orbanes, Monopoly Companion, Second edition. Page 21.

- ^ Anspach, The Billion Dollar Monopoly Swindle, page 132.

- ^ Walsh. Page 49.

- ^ Anspach, The Billion Dollar Monopoly Swindle, page 134.

- ^ Anspach, The Billion Dollar Monopoly Swindle, pages 148-149.

- ^ a b Walsh. Page 51. The original rejection letters from Milton Bradley and Parker Brothers are reproduced on this page.

- ^ a b Orbanes, Philip E. (2004). The Game Makers: The Story of Parker Brothers (First Edition ed.). Harvard Business School Press. pp. Page 92. ISBN 1-59139-269-1.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help) - ^ Orbanes. The Game Makers. Page 93.

- ^ Orbanes, Monopoly Companion Second edition. Page 24.

- ^ Orbanes, The Game Makers. Page 103.

- ^ Anspach, The Billion Dollar Monopoly Swindle, pages 100-101.

- ^ Orbanes, Monopoly: The World's Most Famous Game, pages 75-76.

- ^ Orbanes, Monopoly: The World's Most Famous Game, page 76.

- ^ Orbanes, Monopoly: The World's Most Famous Game, page 78.

- ^ Orbanes, Philip. "Monopoly Memories," booklet, published in 2002 by Winning Moves Games. Included with the reproduction of the 1935 Parker Brothers Monopoly Deluxe Edition set. Page 6.

- ^ a b Orbanes. The Game Makers. Page 95.

- ^ Orbanes, The Game Makers. Page 98.

- ^ Orbanes, The Game Makers. Pages 98–99

- ^ Orbanes, The Game Makers. Page 103

- ^ Orbanes, Monopoly: The World's Most Famous Game, Appendix V, page 211.

- ^ Monopoly Lexicon page for Italy, by Albert C. Veldhuis.

- ^ Monopoly Lexicon page for Austrian Standard Editions.

- ^ Monopoly Lexicon page for early Monopoly editions in The Netherlands, in Dutch.

- ^ Walsh. Page 56.

- ^ Orbanes. The Game Makers. Color photographic insert, page 10.

- ^ English introductory page to the Monopoly Lexicon website.

- ^ Orbanes. "Monopoly Memories." Pages 5–6.

- ^ Sadowski, Passing Go. Page 139.

- ^ Brady, Maxine (1974). The Monopoly Book: Strategy and Tactics of the World's Most Popular Game (First hardcover edition ed.). D. McKay Co. pp. Page 20. ISBN 0-679-20292-7.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help) - ^ Orbanes, Monopoly: The World's Most Famous Game, pages 93–94.

- ^ Orbanes, Monopoly: The World's Most Famous Game, page 94.

- ^ Orbanes, Monopoly: The World's Most Famous Game, page 98.

- ^ Orbanes, Monopoly: The World's Most Famous Game, pages 100–101.

- ^ Orbanes. "Monopoly Memories." Page 2

- ^ Orbanes, Monopoly: The World's Most Famous Game, page 107.

- ^ Brady. Page 25.

- ^ Brady. Pages 26–27.

- ^ a b Orbanes, Monopoly: The World's Most Popular Game, photo insert, page 25.

- ^ Brady. Page 20

- ^ Brady, pages 21–24.

- ^ Anspach, page 303.

- ^ Brandreth, pages 169-174.

- ^ Moore, Tim (2002). Do Not Pass Go: From the Old Kent Road to Mayfair. Vintage UK, division of Random House. pp. Page 4. ISBN 0-09-943386-9.

- ^ Orbanes, Monopoly Companion, Second Edition. Pages 140–142.

- ^ Brady, page 10

- ^ News article from Sky News. Accessed 24 July 2006.

- ^ Orbanes, Monopoly: The World's Most Famous Game, page 188.

- ^ Orbanes, Monopoly: The World's Most Famous Game, page 116.

- ^ Orbanes. Monopoly Companion Second Edition. Page 156.

- ^ Brandreth, Gyles (1985). The Monopoly Omnibus (First hardcover edition ed.). Willow Books. pp. Page 185. ISBN 0-00-218166-5.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help) - ^ Orbanes, Monopoly: The World's Most Famous Game, page 155.

- ^ Brandreth. Page 187.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j 1973–1995 World Champions are listed in Philip Orbanes's Monopoly Companion, second edition, page 171.

- ^ Information on the 2000 World Monopoly Championship from Mind Sports Worldwide's MindZine.

- ^ 2003 U.S. Tournament "Fun Facts" from hasbro.com.

- ^ Press Release on Hasbro.com naming the 2004 World Monopoly Champion.

- ^ Orbanes, Monopoly: The World's Most Famous Game, page 121.

- ^ Orbanes, Monopoly: The World's Most Famous Game, page 122.

- ^ Anspach, The Billion Dollar Monopoly Swindle, pages 104-106 and pages 134-135.

- ^ Anspach, The Billion Dollar Monopoly Swindle, page 249.

- ^ Anspach, pages 269–271.

- ^ Anspach, page 273.

- ^ Anspach, page 286.

- ^ Partial scan of the United States Supreme Court decision to not hear the Anti-Monopoly, Inc. vs. General Mills Fun Group, Inc. case.

- ^ Orbanes, Monopoly: The World's Most Famous Game, pages 120-125.

- ^ Anspach, page 301

- ^ Quotation from the inside cover of the game booklet included with the special Canadian Edition of Monopoly, published in 1982.

- ^ Orbanes, Philip E. (1988). The Monopoly Companion (First Edition ed.). Bob Adams, Inc. pp. Page 190. ISBN 1-55850-950-X.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help) - ^ List of electronic version release dates on monopolycollector.com.

- ^ Orbanes, Monopoly Companion Second Edition. Page 185.

- ^ Hasbro's news release for the new game token in its 1998–1999 campaign.

- ^ Monopoly Pinball page at sternpinball.com.

- ^ a b Orbanes, The Game Makers. Page 170.

- ^ University Games USA website, with Anti-Monopoly

- ^ University Games UK website, with Anti-Monopoly

- ^ University Games France website (click Jeu/Famille)

- ^ Orbanes, Monopoly: The World's Most Famous Game, Appendix II, page 199

- ^ Orbanes, Monopoly: The World's Most Famous Game, photo insert page 29.

- ^ Orbanes, Monopoly: The World's Most Famous Game, pages 136-137.

- ^ Orbanes, Monopoly: The World's Most Famous Game, pages 135–136.

- ^ Announcement of Monopoly slot machines by WMS Gaming winning an award for Most Innovative Gaming Product, January 1999

- ^ Illinois Lottery's "Pick and Play" US$5 MONOPOLY lottery tickets

- ^ Ohio Lottery Monopoly US$2 Instant Game

- ^ Monopoly Bathroom Accessories on Canada-shops.com

- ^ USAopoly's "About Us" web page.

- ^ Winning Moves Games "About Us" web page.

- ^ Web page list of official Monopoly board games published by Winning Moves Games in the United Kingdom.

- ^ Web page list of official Monopoly board games published by Winning Moves Games in France.

- ^ Web page list of official Monopoly board games published by Winning Moves Games in Germany.

External links

Official sites

- The official U.S. Monopoly web site

- Hasbro's Fun Facts Page on Monopoly

- Official Monopoly Quiz (used to be the "Monopoly National Championship Quiz"; same quiz)

- The official UK Monopoly web site

History

- U.S. patent 748,626 – Patent for the first version of The Landlord's Game

- U.S. patent 1,509,312 – Patent for the second version of The Landlord's Game

- U.S. patent 2,026,082 – Patent awarded to C.B. Darrow for "Monopoly" on 31 December1935

- Early history of Monopoly

- Atlantic City 150th Anniversary series of articles from the newspaper CourierPost, which describe the streets of Atlantic City that appear on Monopoly

- Online photo album of many historical U.S. Monopoly sets, from Charles Darrow's sets through the 1950s.